Video file

Ryan Diaz

Towards a Theatrical Design

ABSTRACT

Community, Harana, & Karaoke: Towards a Theatrical Design explores graphic design’s potential as theatrical staging for building community and practicing the difficult and complicated art of loving others through performance.

Studying graphic design as harana, the traditional Filipino custom of romantic serenade, offers a framework to view both mediums as social architectures that propose and transform proximities of relation between people. As in harana, graphic design facilitates in naming, grounding, and organizing social relationships; in taking these affective environments as content and form, both arts align with the nature of performance and staging. Through practice, research, and abstraction, the graphic designer and the haranista possess the capacity to bring people together across space and time. Lessons learned in karaoke further extend these ideas to democratize and amplify the performative nature of graphic design as harana, in addition to modeling role play and collaborative social engagement. Karaoke and graphic design compel dialogical, communal, and collaborative performances for experimenting with conceptions of identity, and incentivize mutual co-dependence. These dynamics mirror the structure of rehearsal.

Community, Harana, & Karaoke imagines a theatrical design in open rehearsal, where failure is safe to pursue. Theatrical design is messy, fluid, and earnest. Its simulations permit access to so much more than what is immediately available under present conditions. This methodology creates zones for processing feelings by designing the scaffolding that supports emotional immersion and social connection. Theatrical design constructs a space for us to imagine the world as it could be, all the while providing a framework for criticality within pedagogies of intimacy, truth, and love.

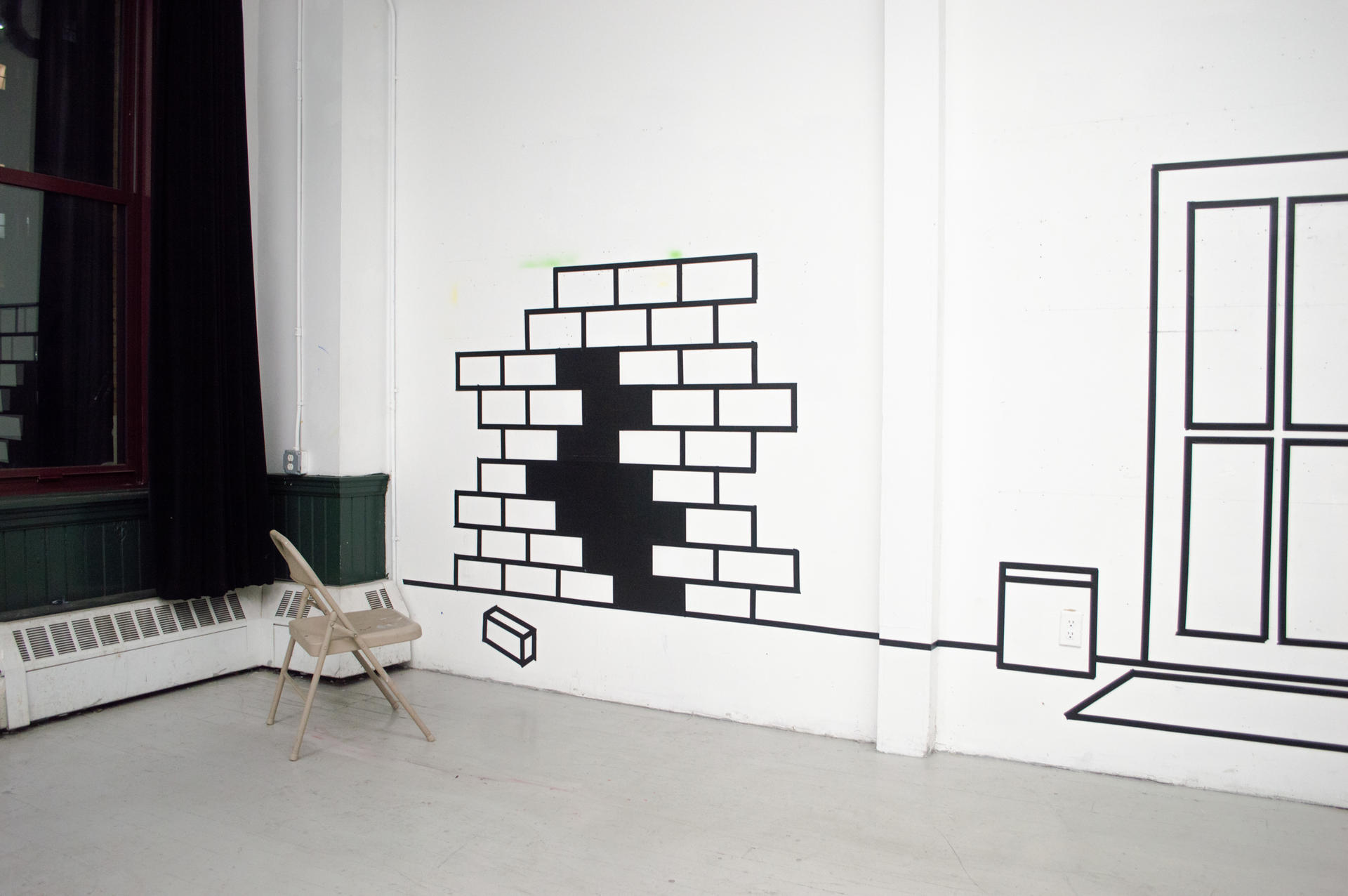

Image

▲ Preview of Community, Harana, & Karaoke: Towards a Theatrical Design by Ryan Diaz, RISD GD MFA 2021

Dancing On Our Own

Performances, graphics for Zoom backgrounds, & video documentation

03:21

2020

Bridging our collective isolation through a suite of user-selected digital backgrounds, Dancing On Our Own connects remote interfaces into a shared virtual nightclub on Zoom. A simple instruction—to dance to “Dancing On My Own” by Robyn—brings everyone together in collective awkwardness, joy, and release. The nightclub may not exist during COVID-19, but its spirit might be summoned through reclaiming digital space and imagination.

Performed by Corinne Ang, Étienne Adams, Romik Bose Mitra, Labelle Chang, Ryan Diaz, Adam Fein, James Goggin, Kevin Ju, Javier Syquia Ásta Þrastardóttir, Jordan Weed, & Amanda Yang.

A Reading Commons (Session #4)

Performance, video documentation

03:53

2020

A Reading Commons: Public Reading Event & Community in Performance

October 24th, 2020, 12 – 2pm at Symposium Books.

A public program developed during COVID-19 to create community through socially-distanced outdoor poetry readings. Partnering with local businesses and the city of Providence, I collaborated with Mae Zhang McCauley and Providence bookstore Symposium Books to create an event for people to read poems out loud for each other in the context of a weekend street fair. We developed a reader of sample poems to pass around to pedestrians who happened upon our reading area. Scott McCullough provided the space and Chance Hãki provided staging for volunteers to recite and perform readings of phrases or passages that amused, delighted, or moved them for the benefit of others.

See more projects on Vimeo.

A Reading Commons was created by Ryan Diaz.

Session #4 developed in collaboration with Mae Zhang McCauley and produced with support from Scott McCullough from Symposium Books, Open Air Saturdays, and Chance Hãki from Providence World Music.

Footage filmed by James Goggin.

Image

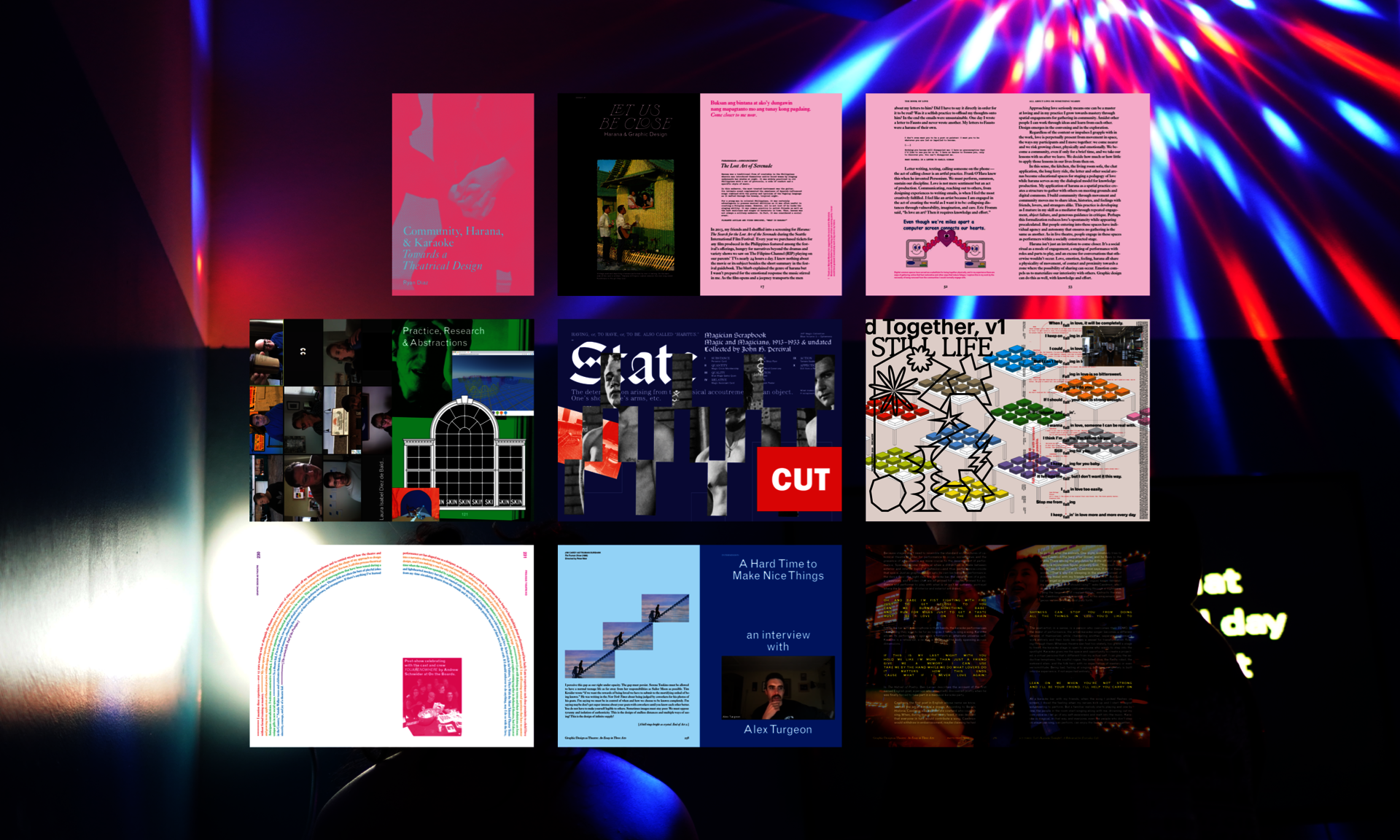

Step into the Wall and Vanish

Workshops, installation, card game, print documentation

Black masking tape

2019

Developed from research on theatrical stage design in establishing belief in imaginary conditions, I developed a formal language using black masking tape to transform spaces into realms for play and improvisation. Step into the Wall and Vanish sought to convey how staging doesn’t need to be high-resolution to serve as a powerful tool in constructing illusory arenas. Even simple interventions can project an audience into an alternative reality where belief and disbelief coexist. Read the project case study for detailed information.

Slow Dance With Me

Performance, video

03:35

2020

"Where Hands Go, Where Eyes Go, Where Face Goes" for the installation Slow Dance With Me by Ryan Diaz. Short films, interviews, and long-exposure photography depict different approaches to intimacy, touch, and social dancing, all with the intention of building up to an installation of a stage primed for an audience to engage in spontaneous slow dancing, complete with a dance floor, romantic music over a sound system, mood lighting, and a romantic ambiance just self-conscious enough to not take itself too seriously. The project has been canceled due to COVID-19, and its realization has become slow itself, swelling with the potential of delay. Its unfinished state is a reminder of the fragility and necessity of social performances.

See more videos from this project on Vimeo.

Dancers: Romik Bose Mitra & Lai Xu

Voiceover: Kit Son Lee

Director of photography: Louis Rakovich

Ram Harness Games

Performance, wearable sculptures, accoutrement

Collaboration with Hannah Lutz Winkler

Performed by Will Mianecki & yours truly (Providence), Taran Atwal & Felipe W. Penna (New York) and yours truly again for the Art in Odd Places Festival 2021.

2021

During the summer of 2020, Hannah Lutz Winkler and I were on a walk 6 feet apart from each other when she asked me to work with her on a project she was just starting to develop. We first started dreaming of a collaboration together after discussing our mutual interest in staging and performance pre-pandemic. When she asked to work with her, I had just returned from visiting Seattle and I spent most of that time in my parents’ house, in perpetual isolation as both my mother and father work in hospitals. The Providence I returned to was completely transformed: empty streets, shuttered restaurants, closed studios. As Hannah explained her research on ram harnesses and explained the six-foot long wearable sculptures she was creating, I was intrigued by the kinds of movement they would conjure. The daub at their ends both mark and replace contact between two people. Weeks later, wearing the harnesses in movement practice, I was fascinated by how they served as new appendages for contact. They felt like safety bumpers with their distance establishing the prescribed safety threshold so our play would remain responsible.

The pandemic ushered in a new landscape for making work and being with others. This world was pocketed with new social rituals like a mandatory two-week quarantine after arriving in my new apartment, charmingly awkward elbow greetings when I could finally walk outside, and the paranoia of standing anywhere near a stranger. Despite these efforts, in December 2020 Rhode Island topped the list of regions with the highest infection rates in the world. These efforts weren’t enough to keep Rhode Island safe.

As the pandemic descended upon a world more-or-less unprepared to handle a full-blown global health crisis, history repeated as the spectres of the Black Death from the 14th century and the 1918 flu pandemic (also known as the Spanish Flu) haunted personal and federal mishandling regarding the virus. “Ring Around the Rosie,” is one such spectre. The factual relation between the game and the black plague it supposedly depicts matters less to me than how a children’s game can bear the weight of death and decay in its origins. Children’s games are made up of equal parts danger and delight. “Crack the Whip” was banned on my elementary school playground with a history of broken limbs and urban legends of fatalities to support its prohibition. Play, as in rehearsal or practice, is also a way of preparing ourselves for the more serious, dire situations in life. Over the months of preparation and development, Hannah and I discussed how play provides safe and practical conditions for experimentation with risk.

The game that easily maps onto the COVID era is “Red Rover”: two teams of players link arms across from each other and take turns calling over an opposing member who runs and crashes into them, attempting to break the human chain. As with many other childrens’ games, Red Rover is incredibly dangerous.

Isolated from each other in quarantine for our own good, people still crave connection in the face of risk. New cases arise when people can’t help themselves, congregating in defiance of restrictions, just as I and the other kids on the playground played Red Rover when the playground attendants weren’t looking. We called each other over despite the harm we might cause to ourselves and others. Not to say that I condone this behavior, but that I tragically understand why it happens.

These games Hannah and I developed are simple metaphors. Two players perform the new rules for engagement with others in the COVID era, the harnesses giving form and physicality to invisible distances. Closing one’s eyes and seeking the other while they try to get away; rushing towards one another desperate to leave a mark; moving quietly and solemnly in step with each other while avoiding touch at all costs: these are only a few choreographies that express what intimacy looks like in 2020 and possibly beyond. The fact that it was literally impossible for us to hold these games in the early months of development without violating state decree only reinforced how risk and play are inextricably linked. The project’s capacity to also explore masculinity, competition, and collaboration excites me for how adaptable these metaphors are beyond disease, especially when I am so tired of fearing for the health of my loved ones.

This project has revealed to me how disease and danger have always been simmering beneath every interaction, how the harm we might suffer through contact is a negotiation we weigh against the rewards of intimacy, both physical and emotional. The need to suppress this virus is more important than any personal inconvenience but how will we relearn how to be with each other if and when the time comes for reunion in crowded bars, busy workplaces, and civic life? It’s important we don’t return to the ways we behaved before, that we learn from the carelessness that set off this incredible, preventable loss of human life. The rituals we perform as social beings will remain, but how we approach each other will be different. These games represent how Hannah and I are learning to play with others while keeping each other safe from harm.

Image