ABSTRACT

As we move further into the Anthropocene — an epoch of geologic time where human activity has caused significant impact on the planet’s natural systems — we can no longer ignore the environmental consequences of our actions. The artificial disconnect between humankind and wilderness has caused us to create built environments that reinforce a false separation from natural landscapes.

Modern architectural movements push us towards surroundings that create disconnect from our sensory relationship to matter and temporality. We must engage with the inevitable decay of the built environment to restore our neglected senses. Reconnecting architecture to local ecologies through adaptive reuse will introduce a true form of landscape urbanism through which architecture and nature become codependent, contributing equally to the human experience.

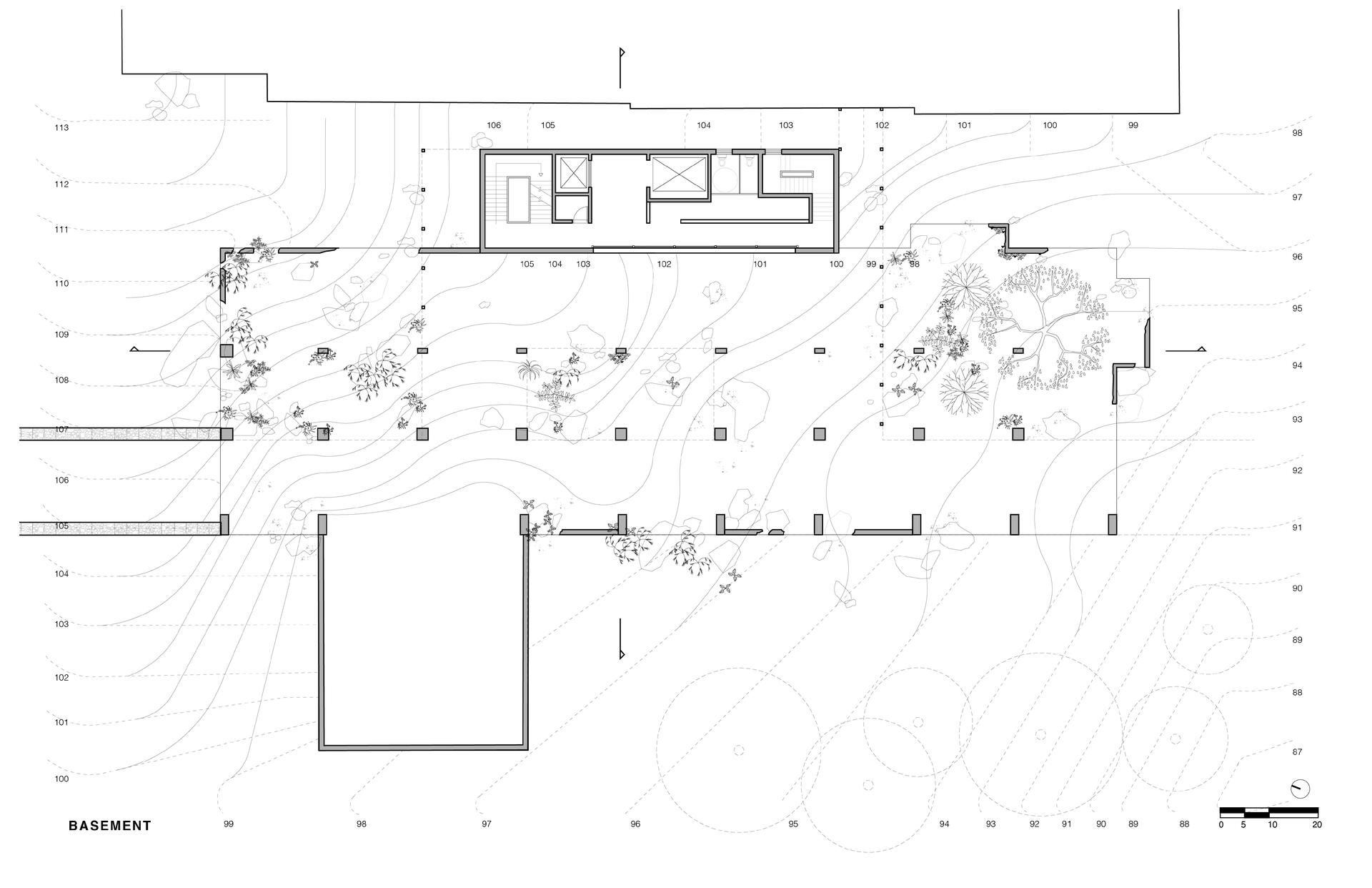

The constructive disintegration of Philip Johnson’s List Art Building at Brown University in Providence, RI explores methods to repair sensory connections, restore environmental balance, and critically engages with architecture's singular narrative of control throughout history. Catalyzing decay to break the building’s rigid geometry creates a more porous structure and fluid human experience, while micro-interventions allow non-human cultures to consume the building over time: reconstructing this monolithic Brutalist structure to reveal layers of history, cultures, and materiality.

MAN'S RELATIONSHIP TO NATURE

Image

Image

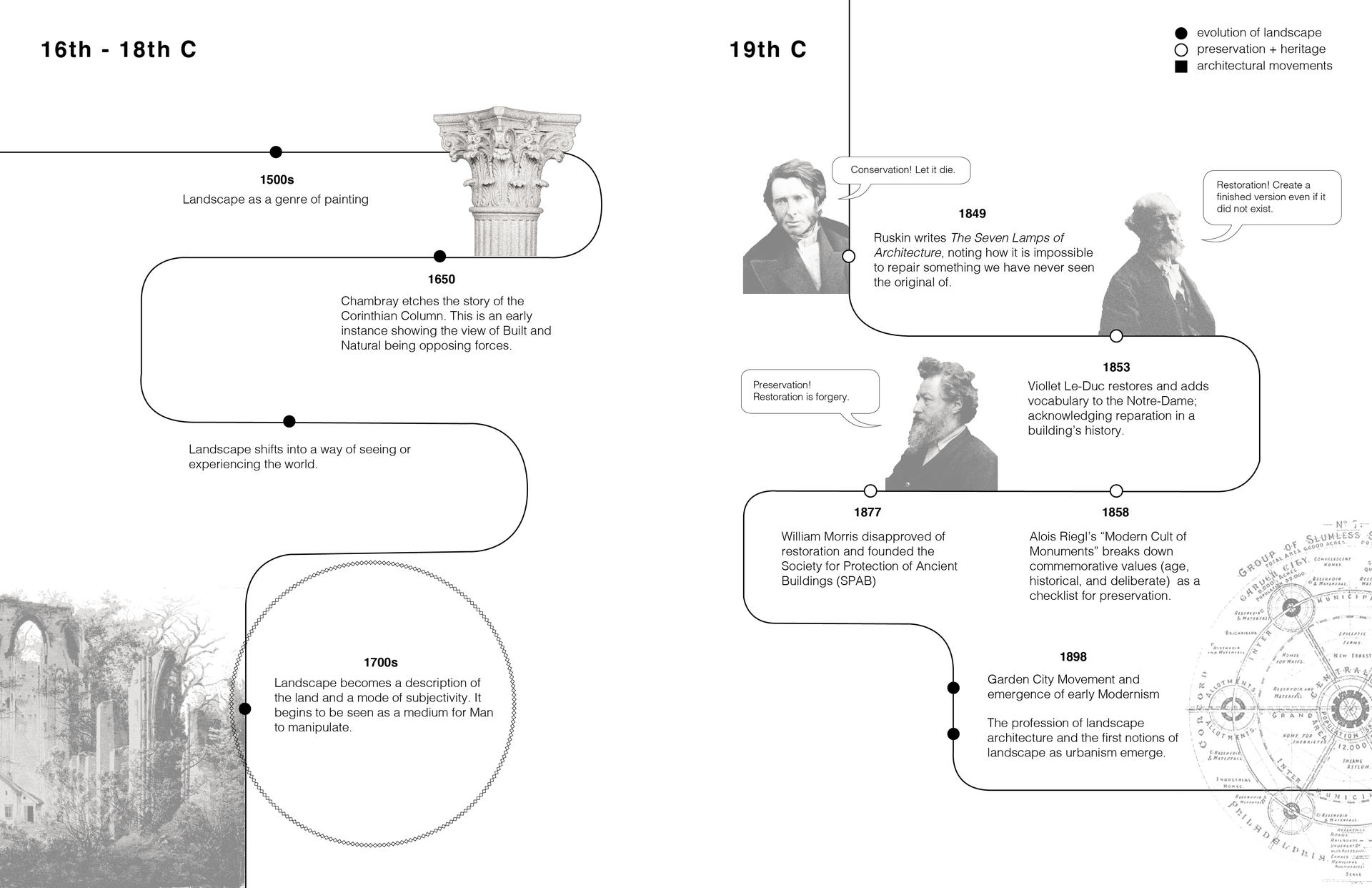

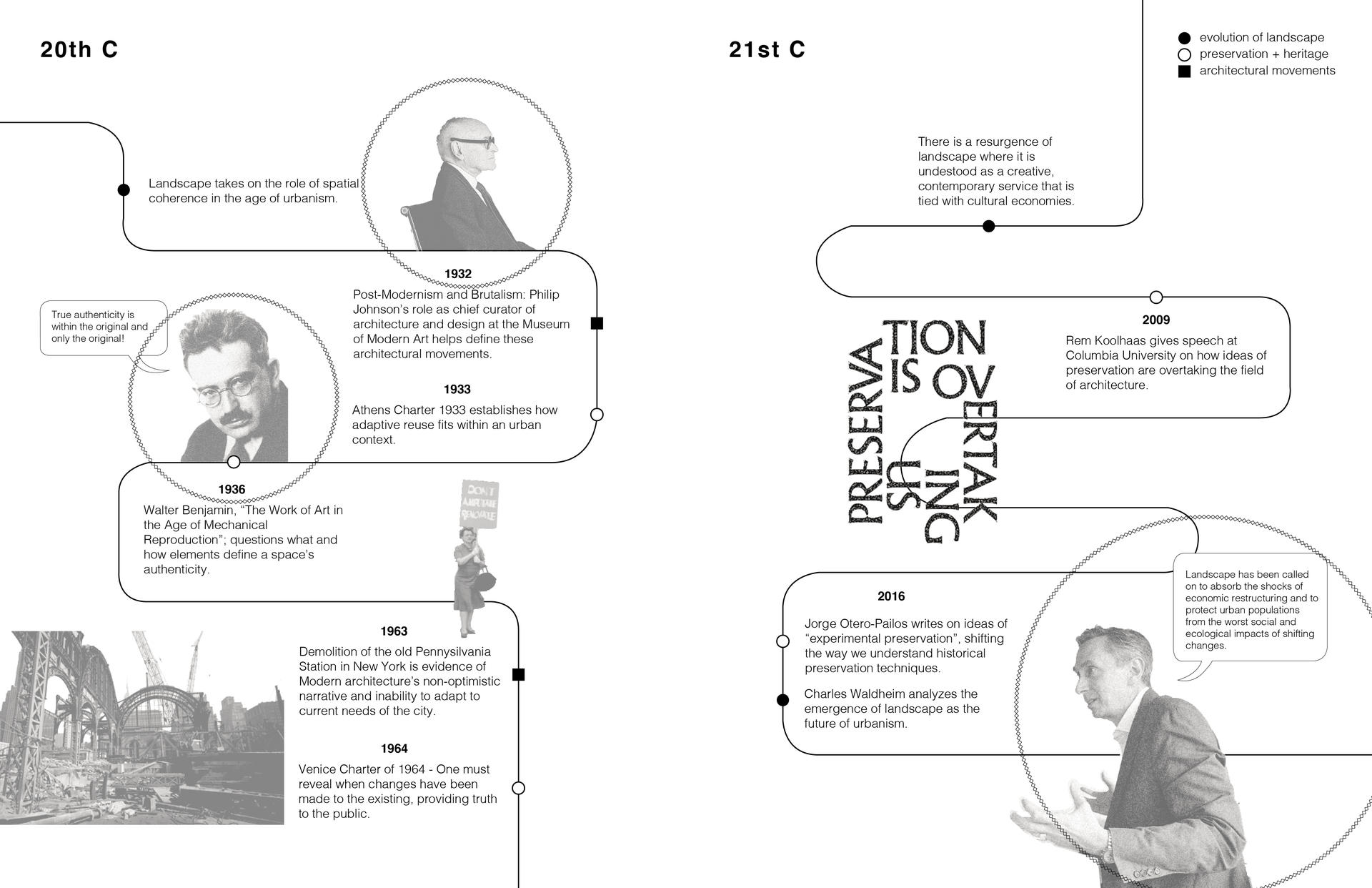

▲ Looking critically at man's relationship to nature, there is an assumed separation between humans and natural systems.

▲ By the 1700's, we are seen as so separate that we begin to control the landscape.

▲ 19th century advancements in technology lead to shifts in understanding in how we perceive the history of the world.

▲ Architecture moves to the forefront of expression, leading to Modernism.

▲ Overuse of architectural trends of glass and the color white lead to spaces void of sensory relationships — Walter Benjamin raises questions on architecture's role in creating authenticity of a space through materiality.

▲ In the 21st Century, landscape begins to emerge as a leading role in urbanism but green spaces implemented do not contribute to the longterm resiliency of natural systems that are currently broken.

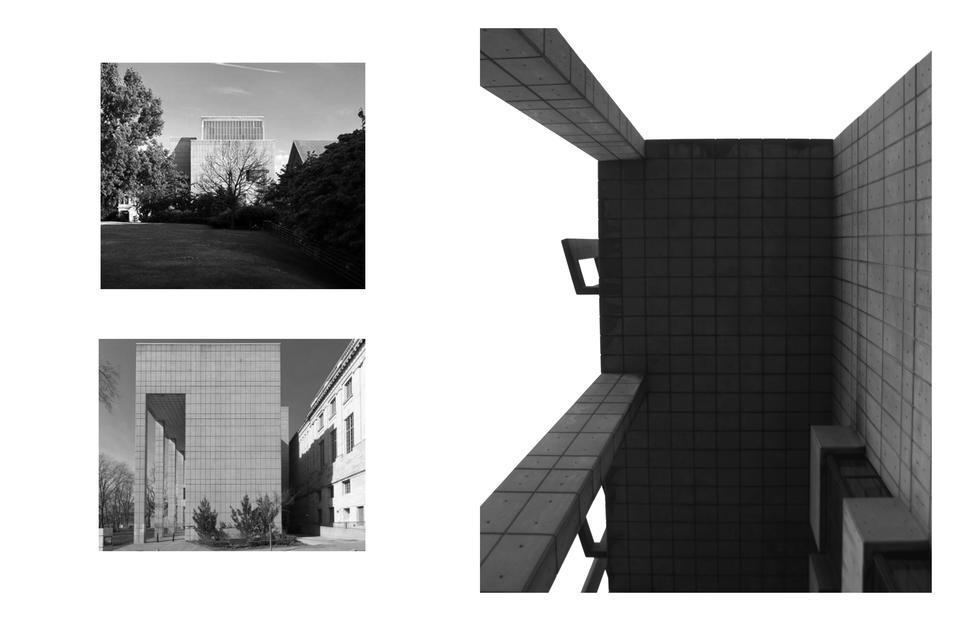

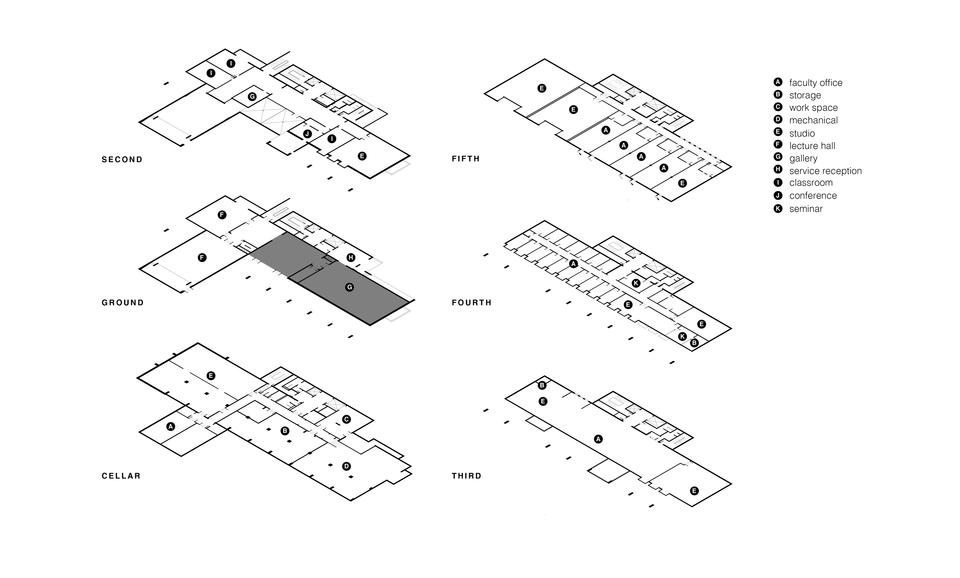

LIST ART BUILDING

The List Art Building was designed by Philip Johnson and built in 1971 for Brown University as their Visual Arts and Art History department along with a public gallery space. It is located where RISD and Brown’s campus meet, adjacent to the John Hay and John D Rockefeller Libraries.

While Philip Johnson and his personal interests are not the target of this thesis, it is necessary to address him as a layer of architectural history and a major contributor in the legacy of Modernism. Johnson’s fascist political history and this personal interest in power manifests itself into his architectural designs. Because the built environment is a representation of our ethics as a society, it is necessary for the field of architecture to address its unethical past through adaptive reuse.

List Art represents many of motifs of modernism that Johnson promoted and overtakes the site, blocking the John Hay Library's views of downtown Providence. The interior organization has very limited connection to the city and the interior spaces have almost no connection to each other or to the city context.

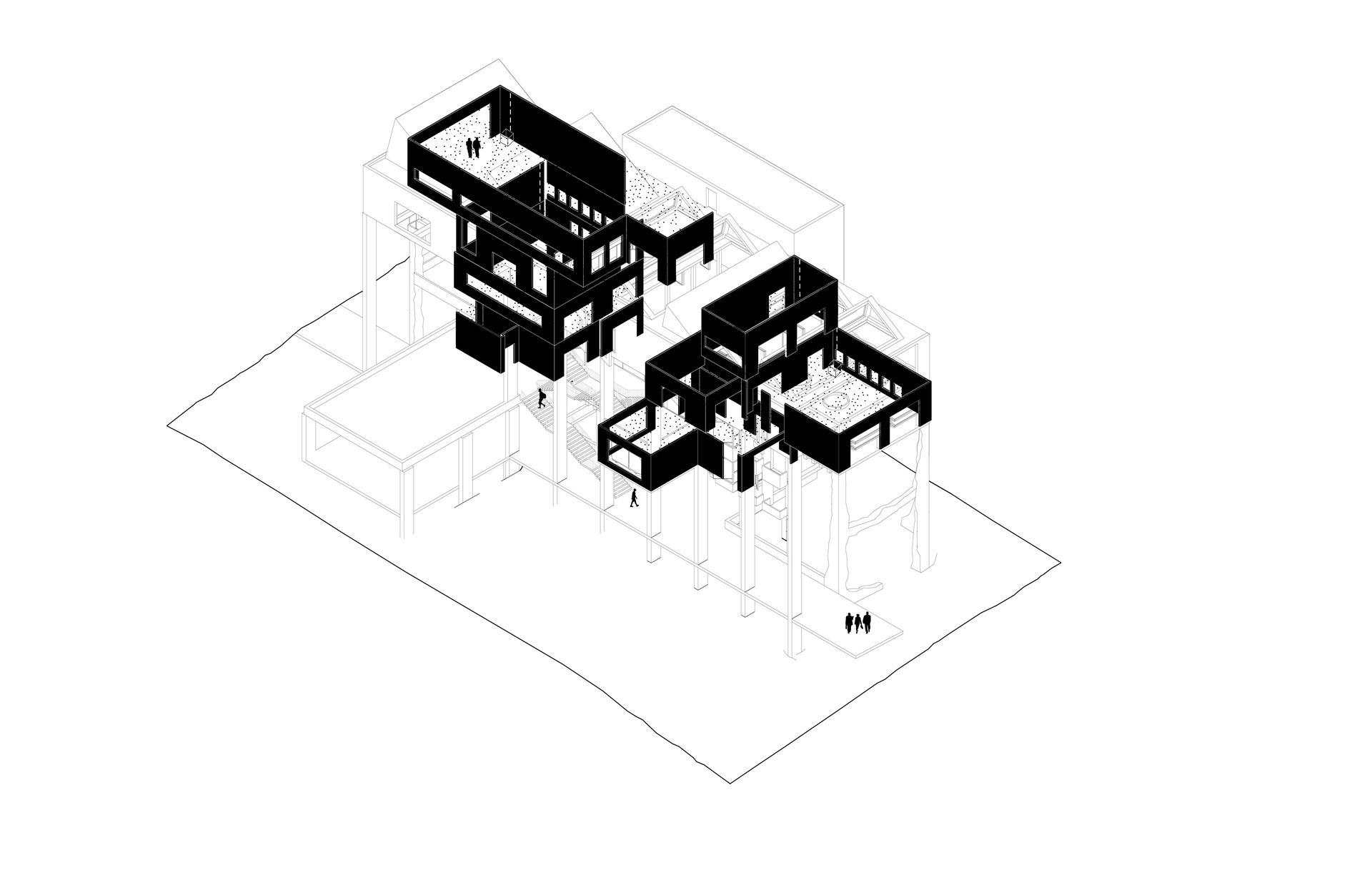

DESIGN STRATEGY: DECONSTRUCT / RECONSTRUCT

Image

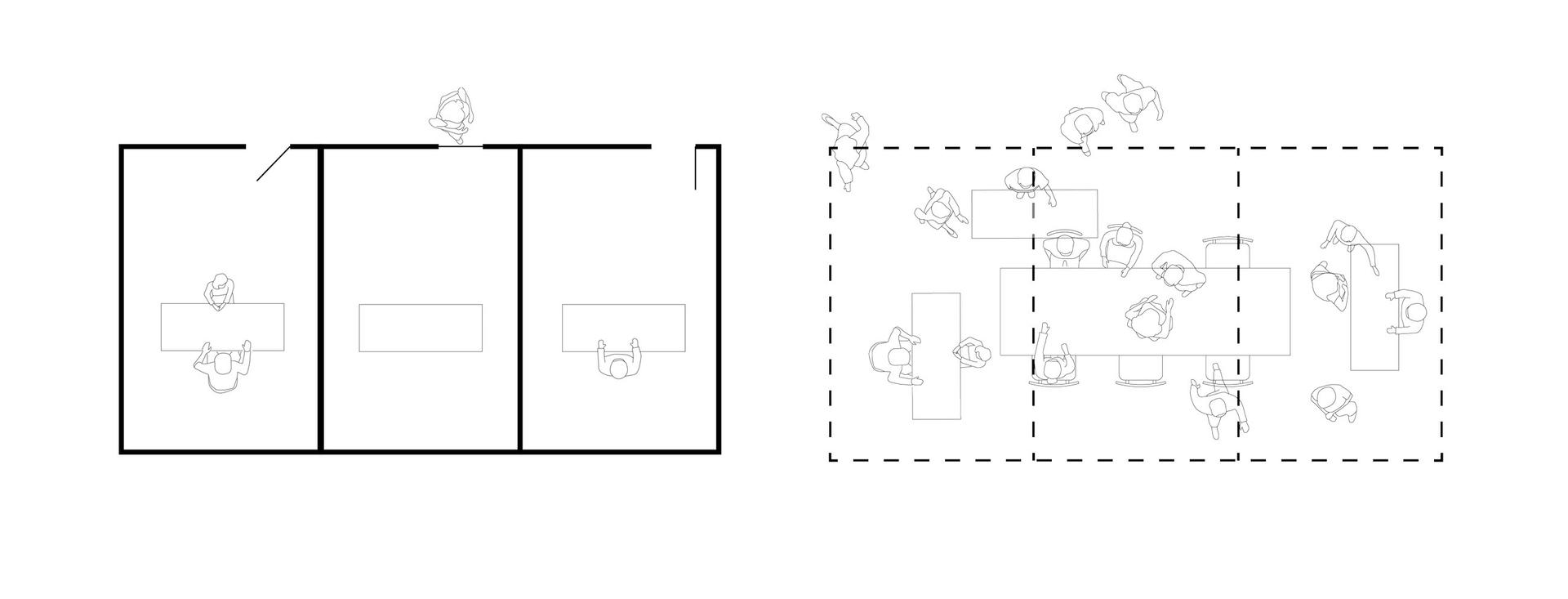

RIGID / FLEXIBLE

Image

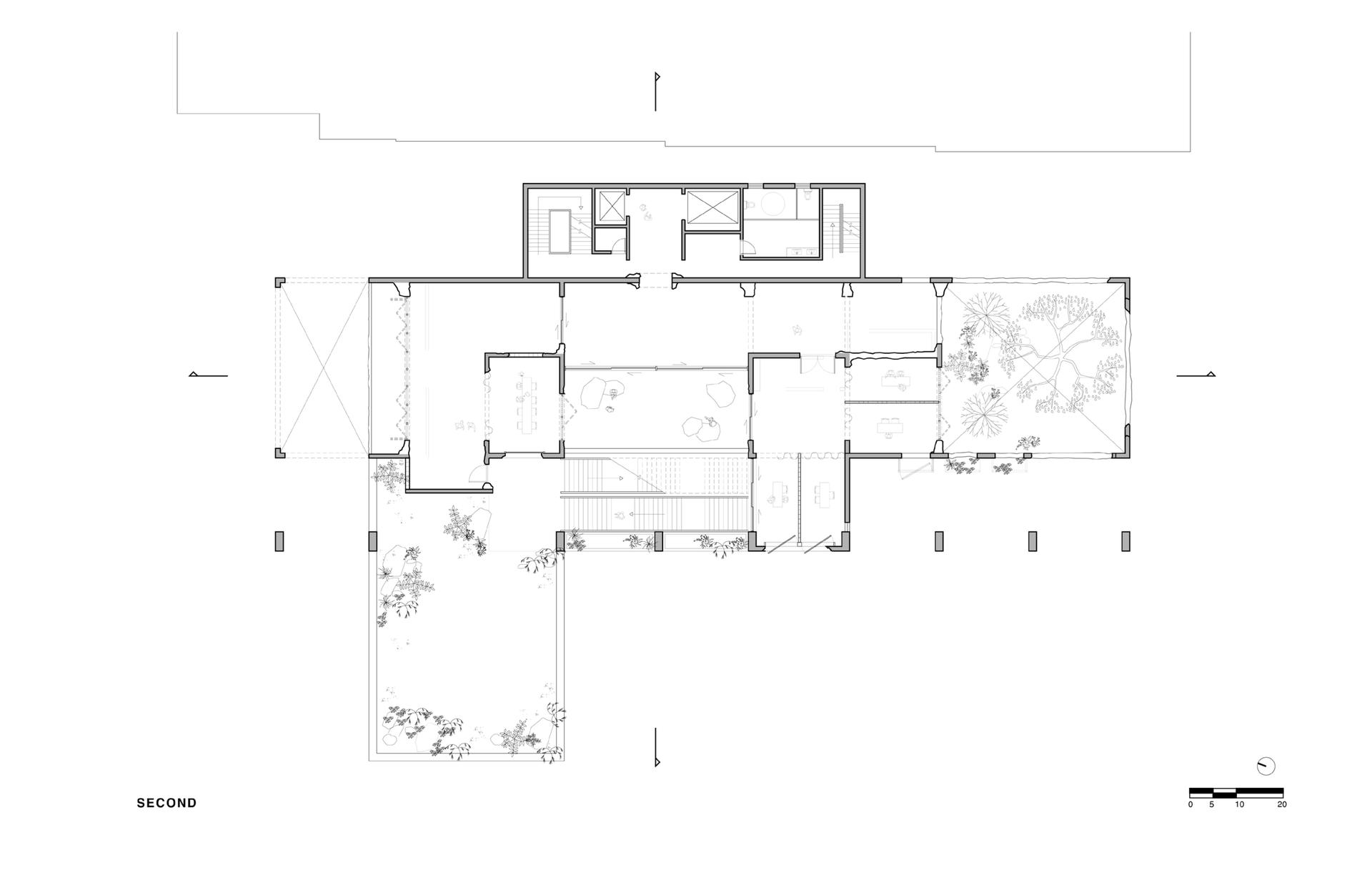

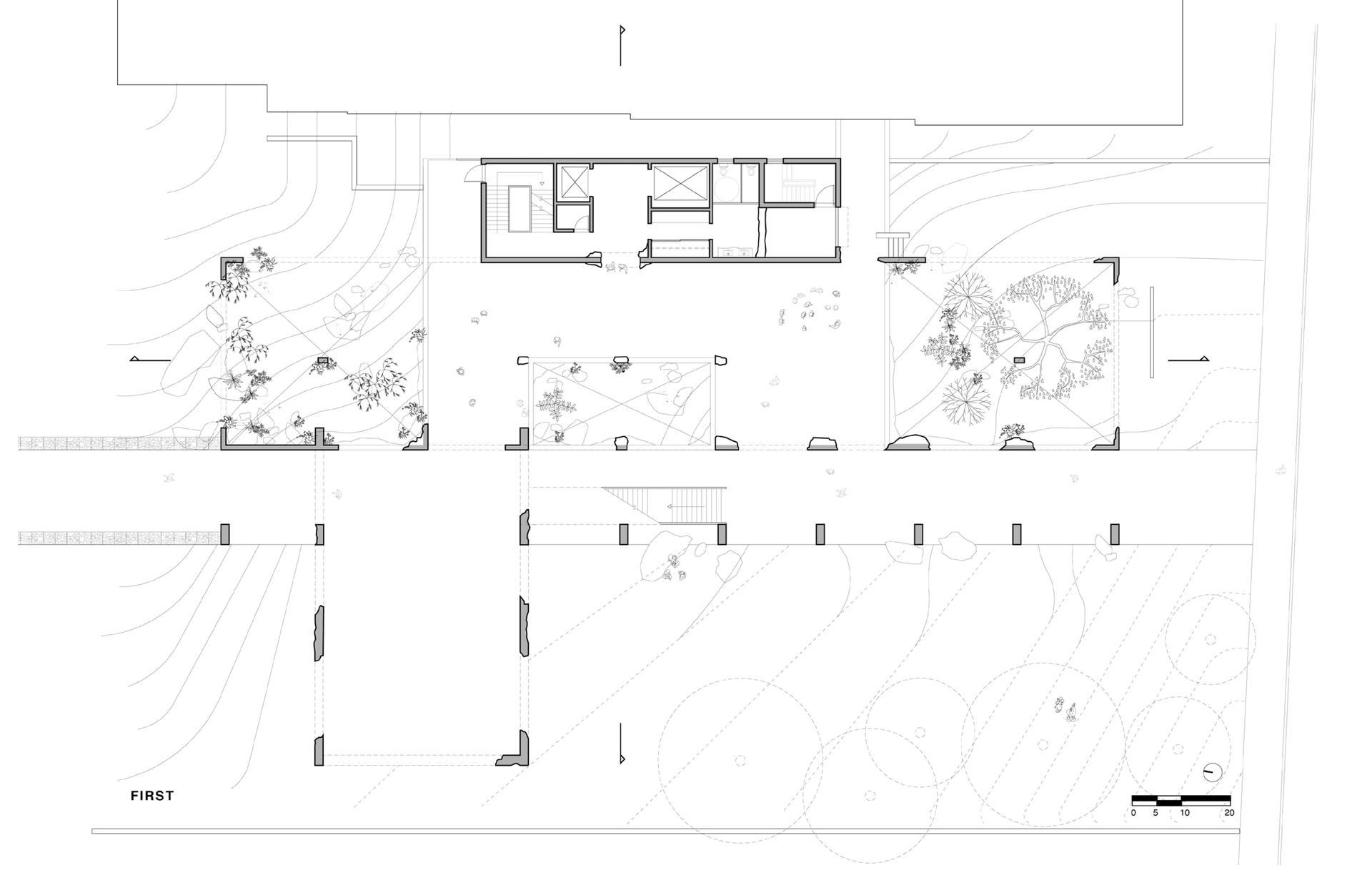

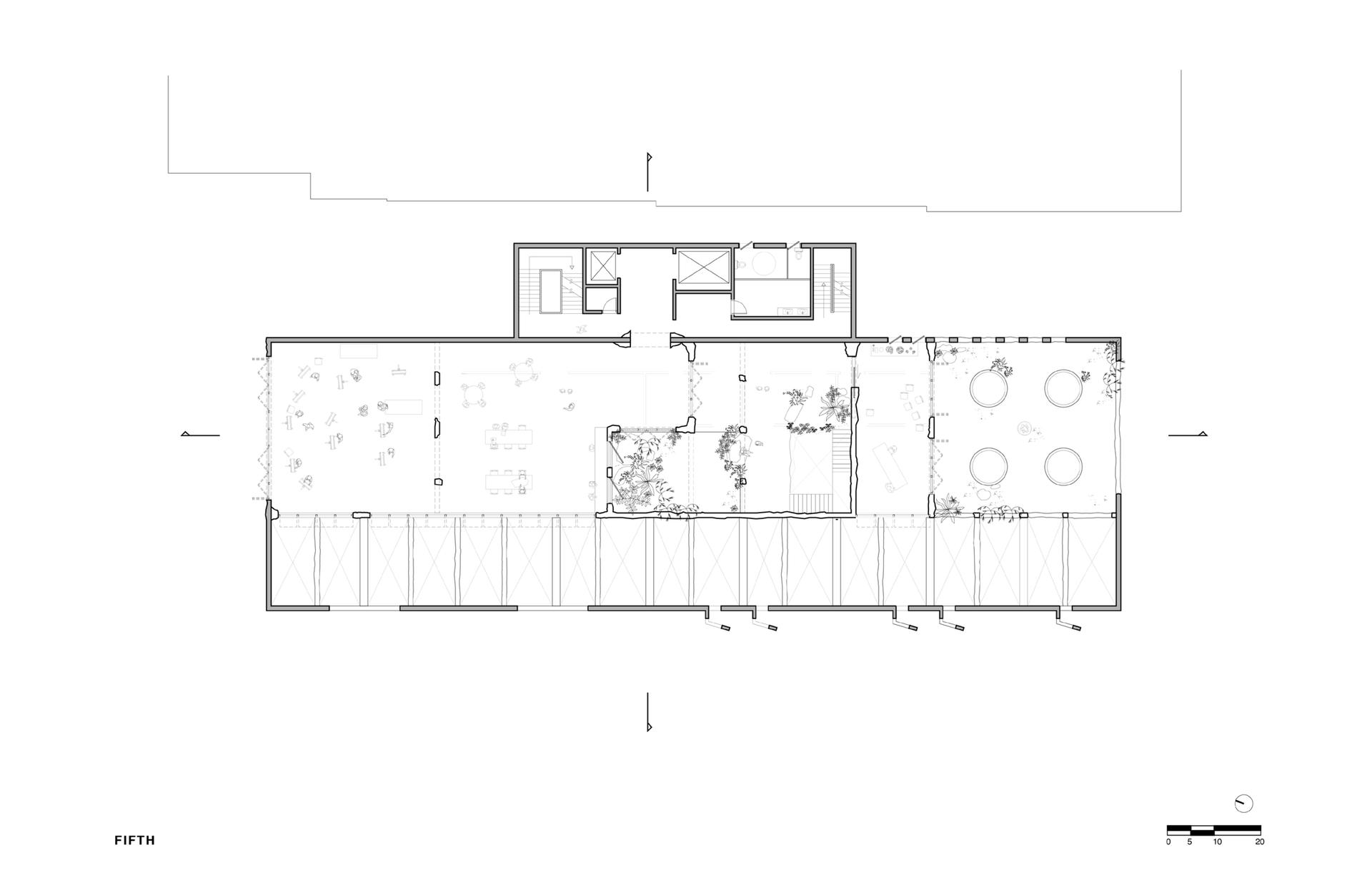

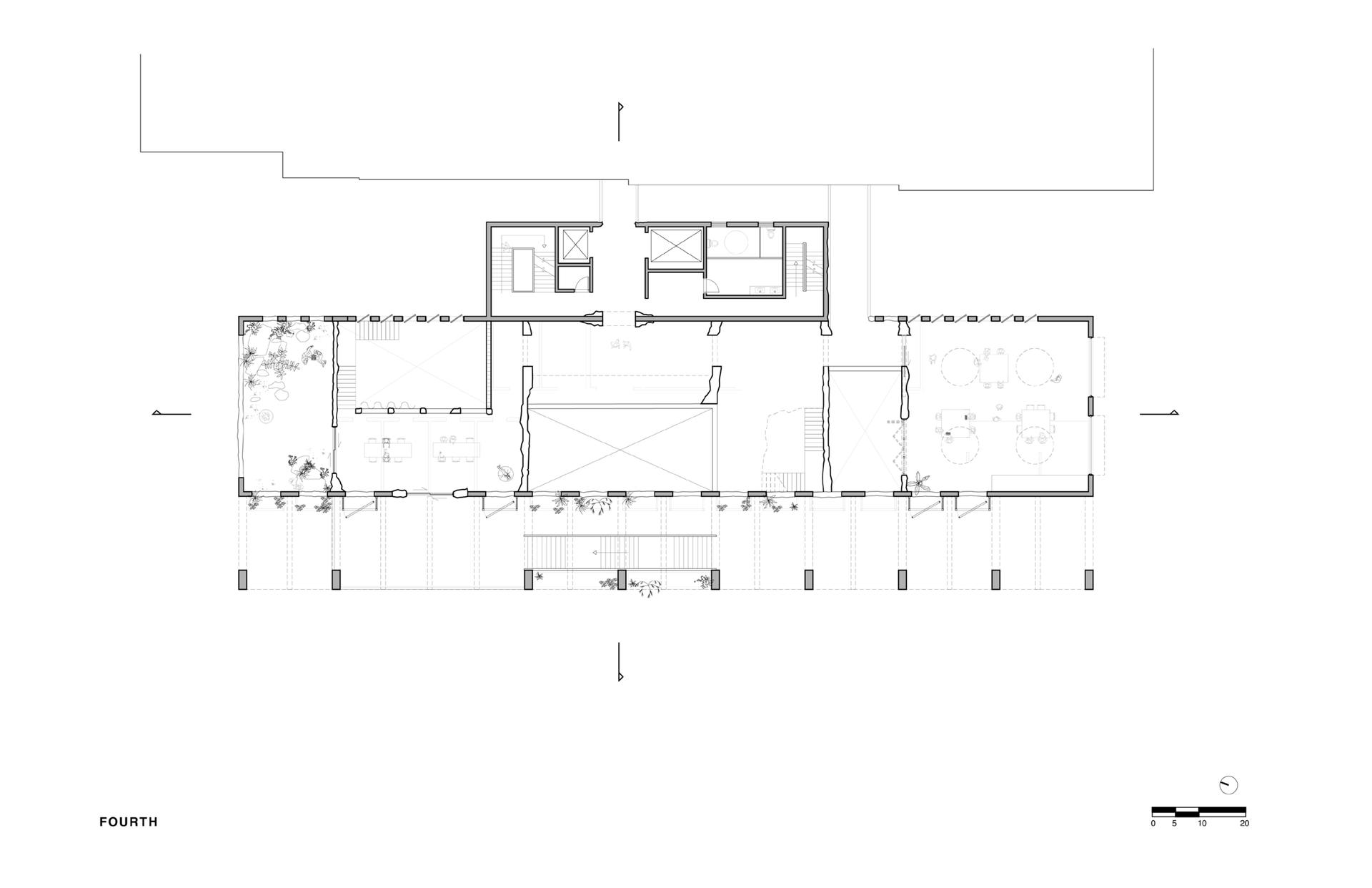

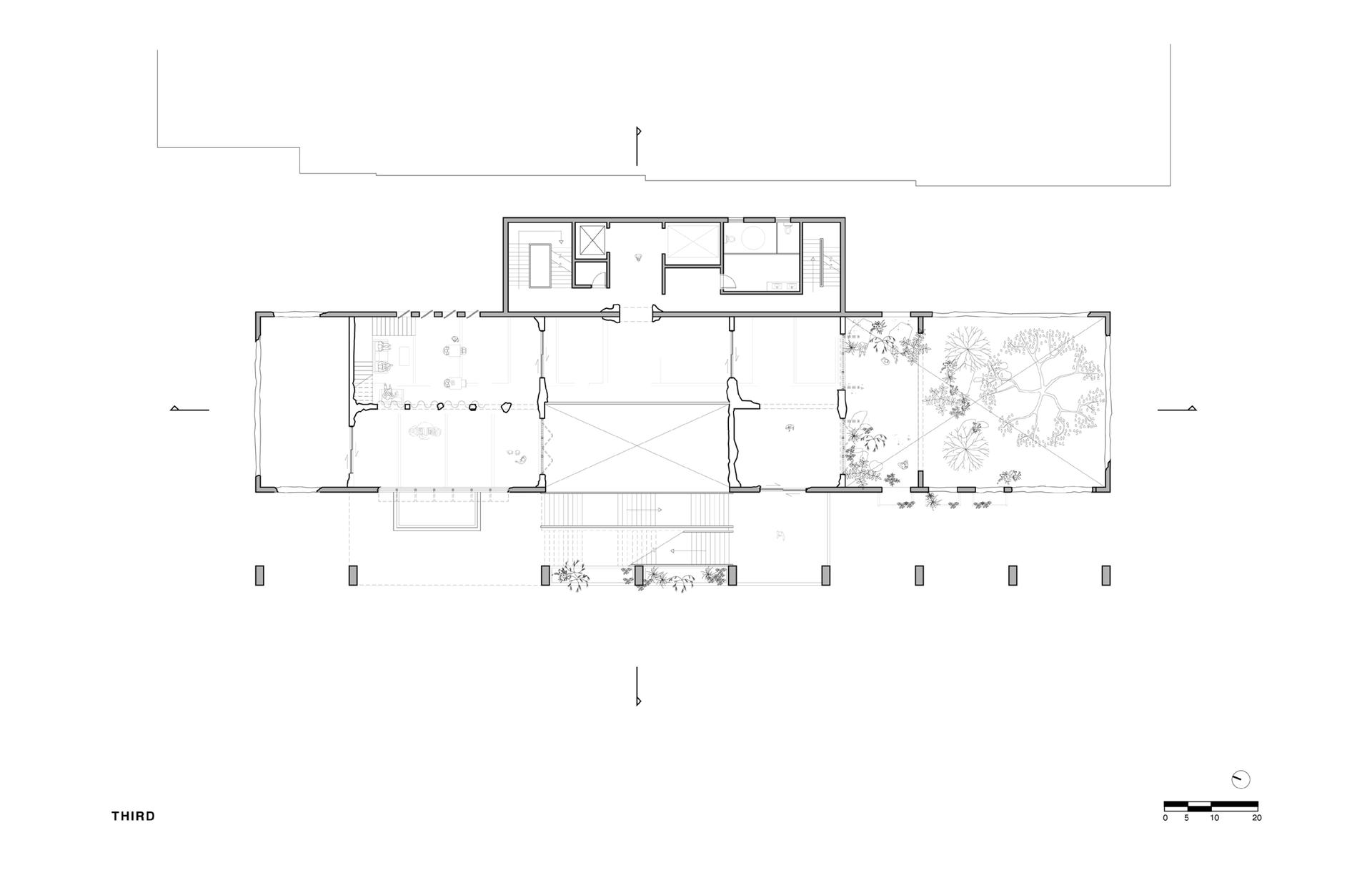

Deconstruction through the redefining of program into a more fluid structure allowing for a degree of flexibility in spaces.

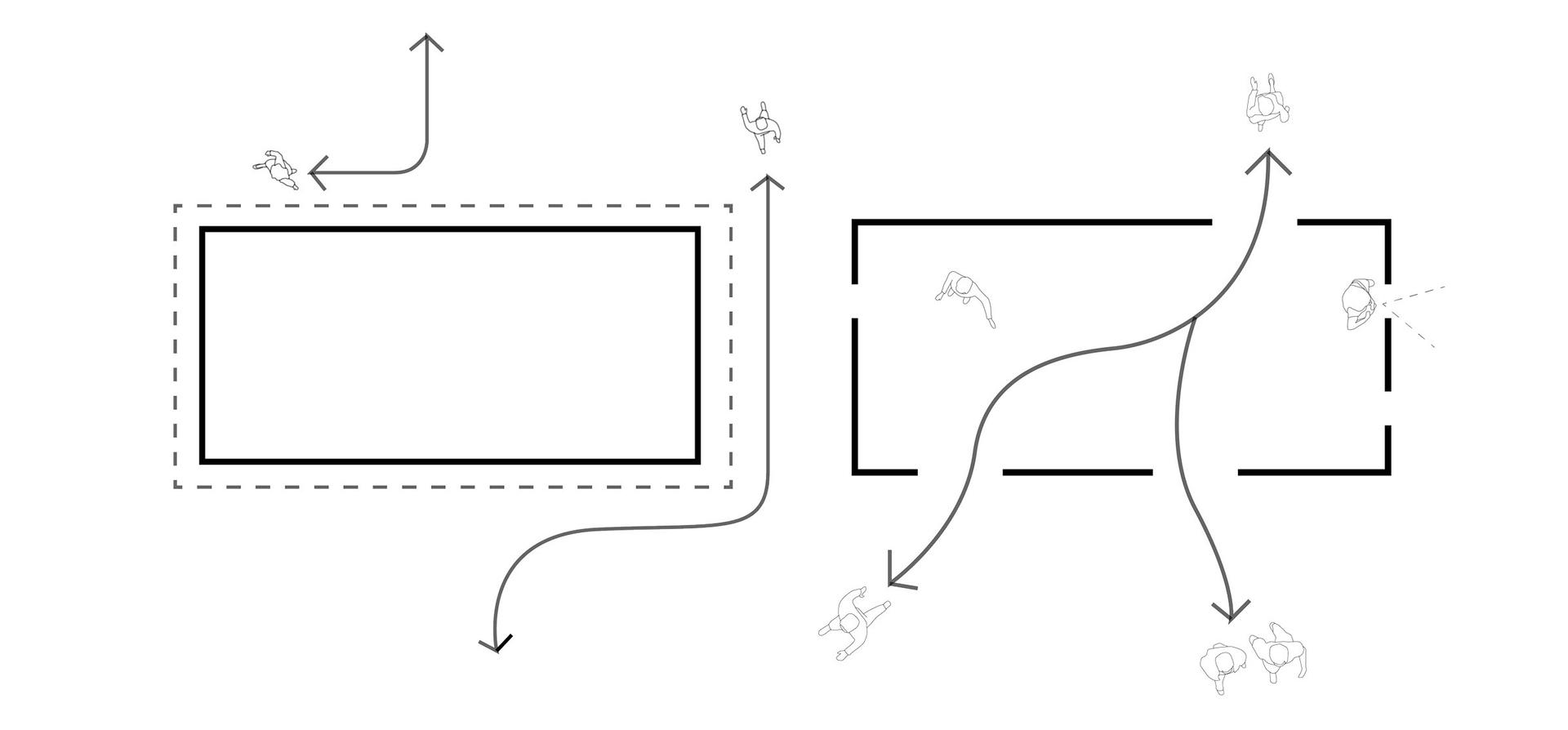

INTERNALIZED / INTEGRATED

Image

Reconstructing the way architecture relates to the city, becoming more integrated and shifting the user from a pedestrian to citizen.

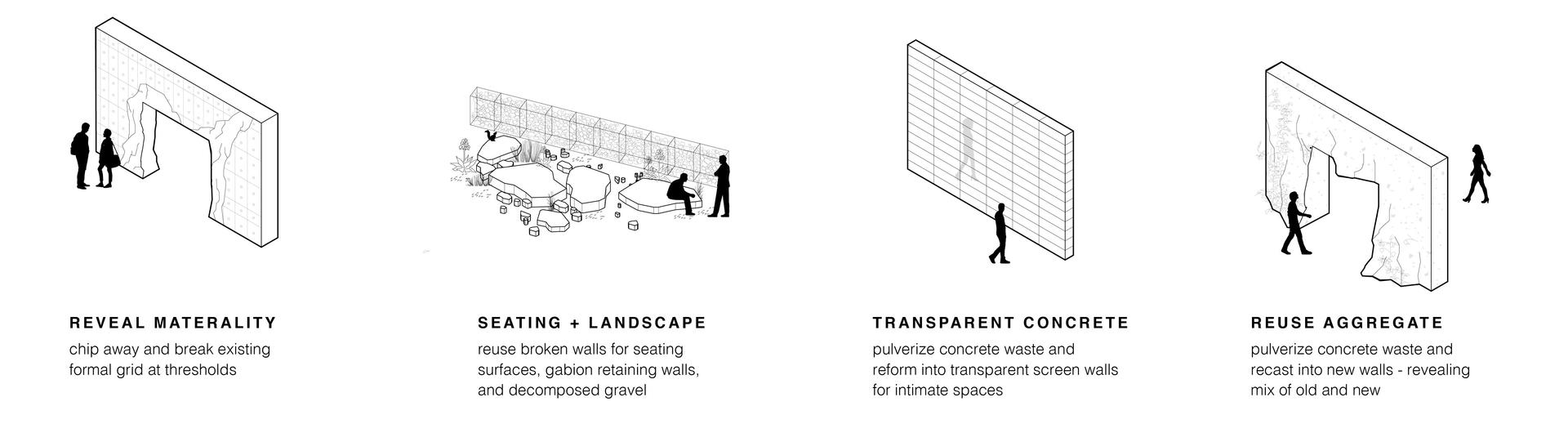

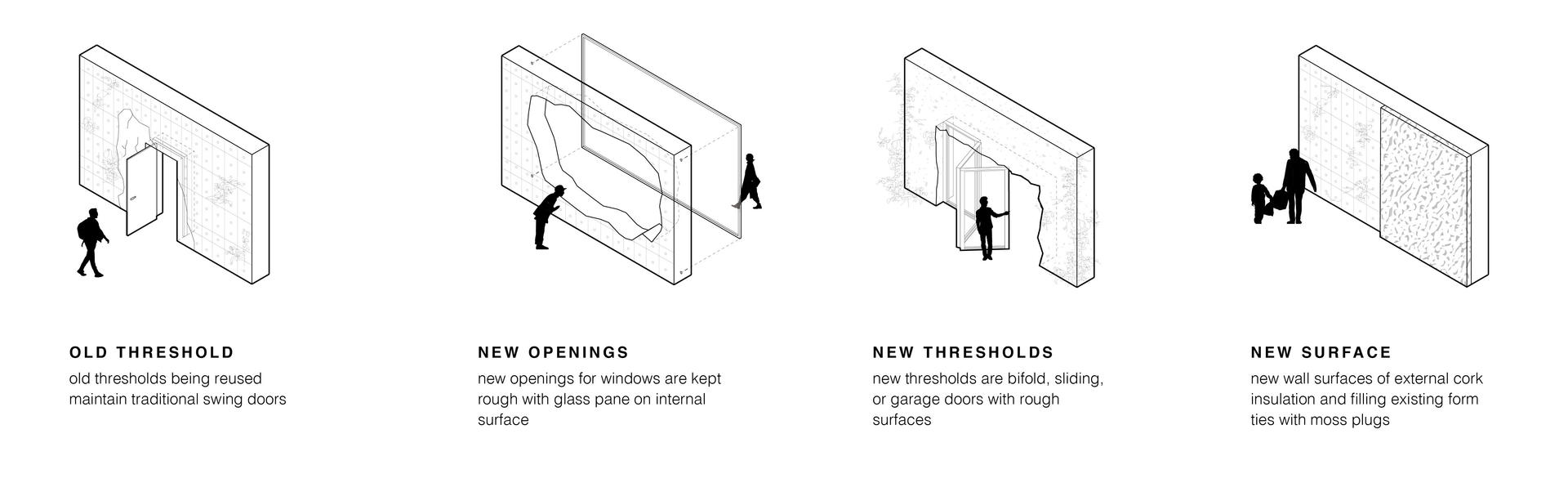

Human-scale interventions show the progression of the deconstruction and reconstruction process: the lefthand side being the most minimal form of intervention while the right shows the maximum.

Image

Layers of time visible through evolution of rigid thresholds and surface patterns to a softer surface which evolves over time.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

SPATIAL TYPOLOGIES

INTIMATE

A transparent concrete screen wall provides and acoustic barrier while still maintaining visual connectivity. Meant for one-on-one meetings, individual work, new faculty offices, reading, listening, and pondering.

CLUSTER

Designed for groups of seating for typical classroom set ups, public workshops, temporary galleries, and builder spaces.

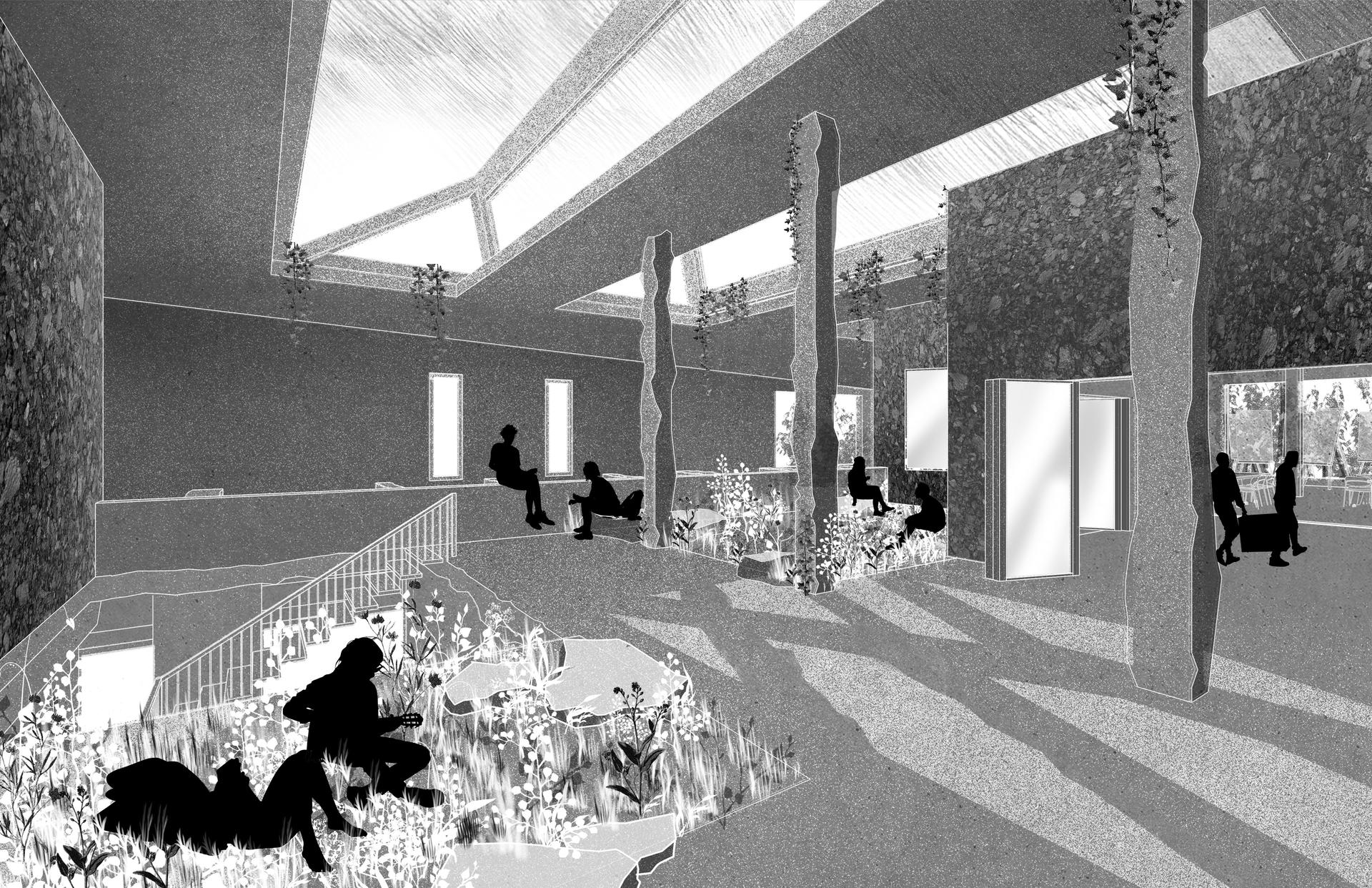

SOCIAL

This double height space is designed to feel more public with connection to outdoor green spaces on both levels and promotes social interaction by having visual and acoustic connection between spaces. It is meant for group work, group faculty meetings, social gallery openings, and club meetings.

COLLECTIVE

Larger collectives spaces for studio work during school semesters, large assemblies, lectures, along with large public workshops during summer.

ENVIRONMENTAL STEWARDSHIP

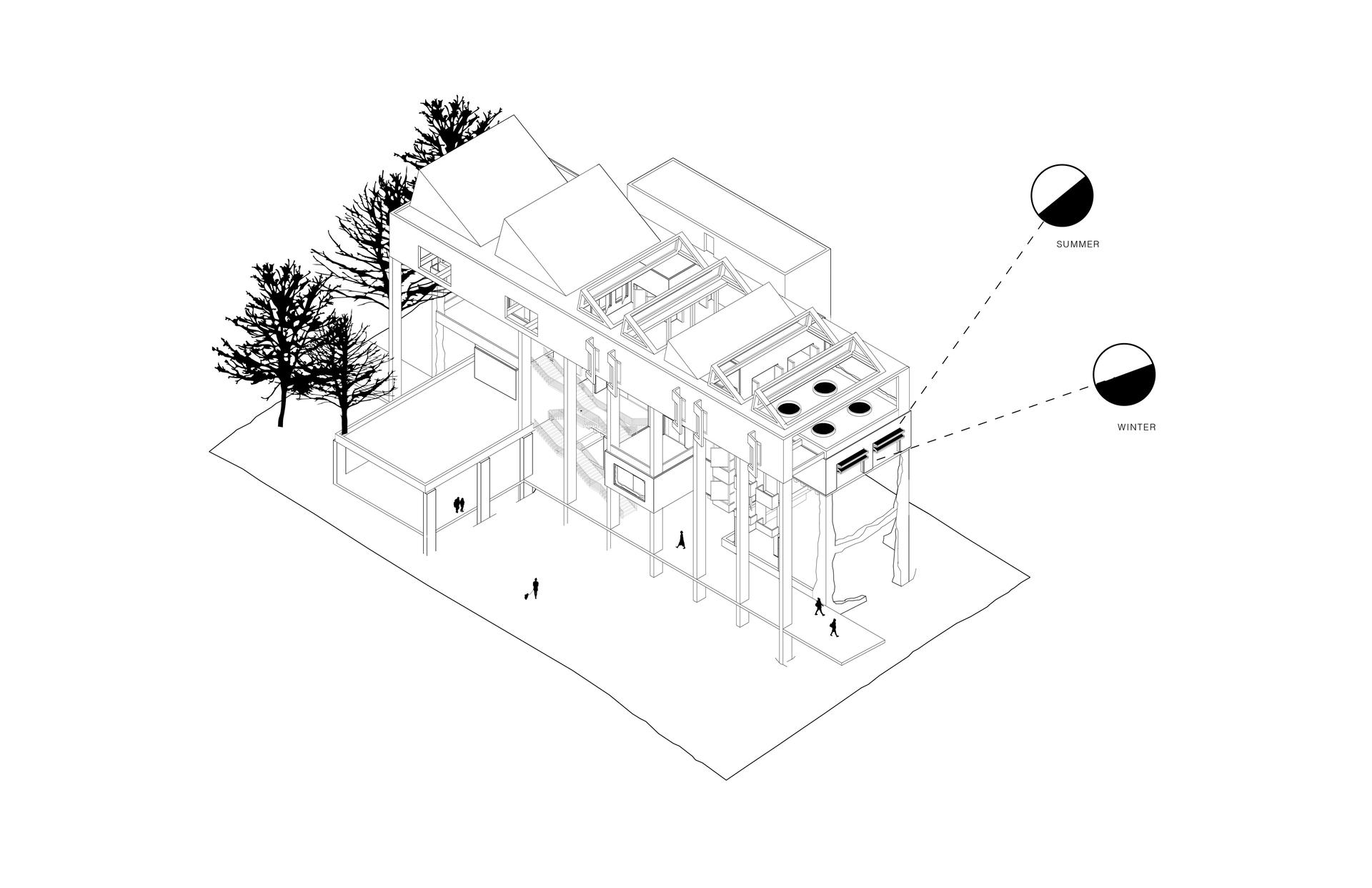

DAYLIGHTING

Image

▲ Openings maximize natural light while garage doors open during the summer to become awnings, blocking direct heat gain.

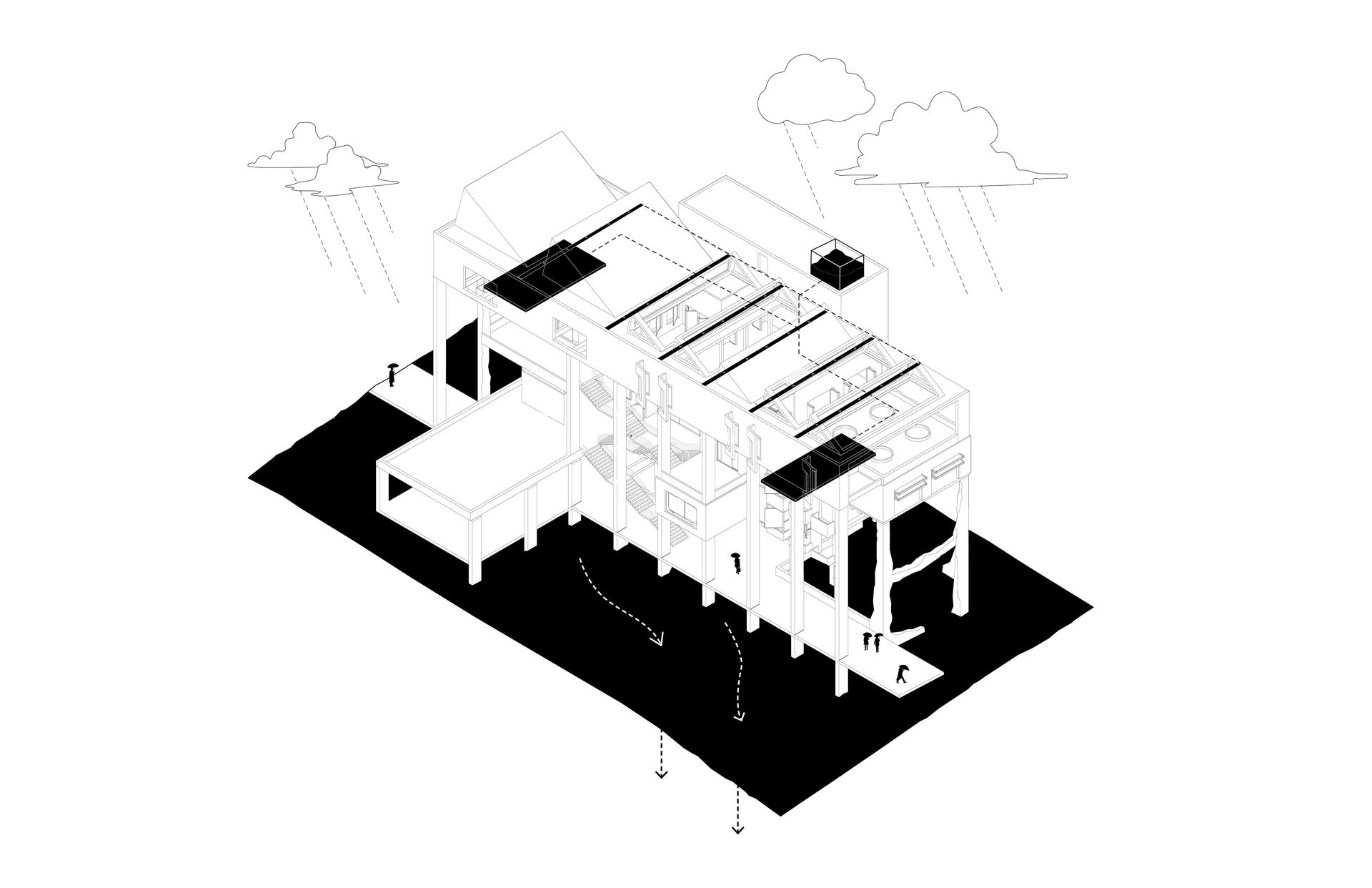

RAINWATER COLLECTION

Image

▲ Rainwater capture on roof directs water to cistern which utilizes gravity to feed water into covered vegetative areas. Water on ground plane is allowed to penetrate down into water table.

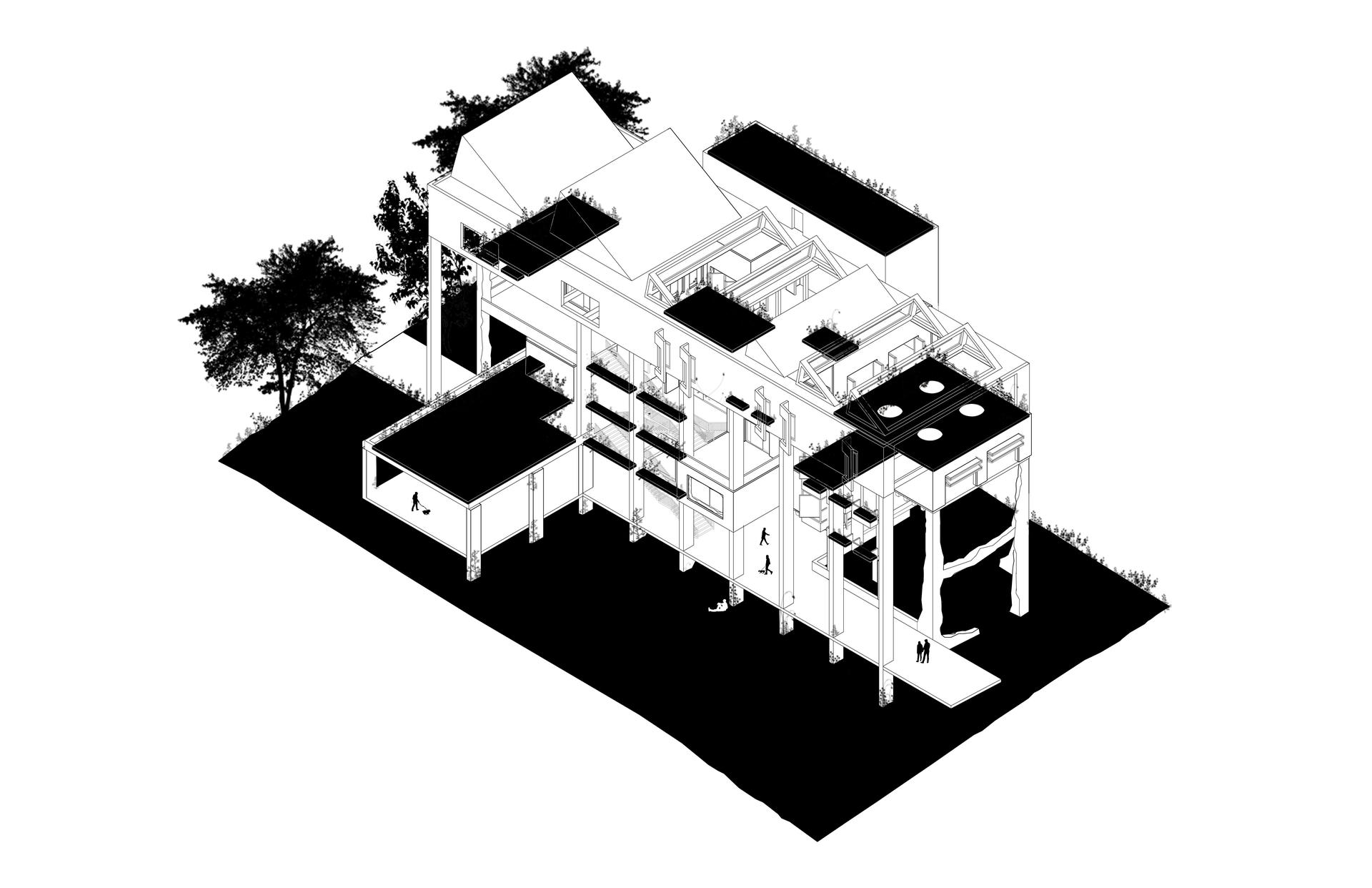

RESTORATION

Image

▲ Implemented green spaces to evolve over time with little to no management.

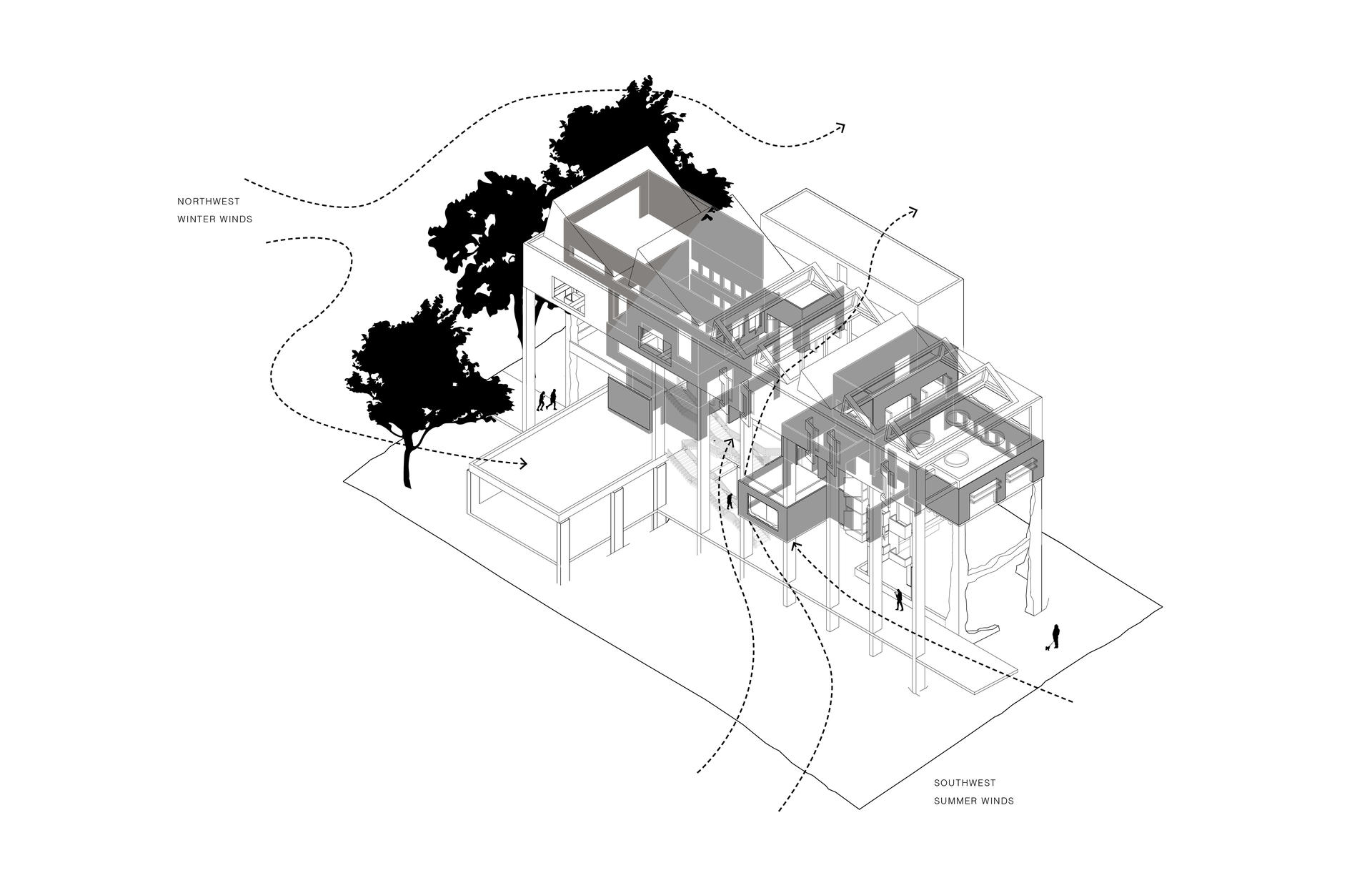

AIRFLOW

Image

▲ NW winter winds redirected by tree plantings around the building while SW summer winds channeled through core of the building by convection, ventilating the spaces passively.

INSULATION PODS

Image

▲ Exterior cork insulation added with spray-in hempcrete as ceiling insulation — both carbon sequestering materials.

ENERGY

Image

▲ Energy harvest via PV panels feeding air source heat pump for mechanical ventilation when necessary.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

ENDNOTES

1. Waldheim, Charles. Landscape as Urbanism: A General Theory. Princeton University Press, 2016.

2. Ibid.

3. Pallasmaa, Juhani. "Matter, Hapticity and Time Material Imagination and the Voice of Matter." Building Material, no. 20 (2016): 171-89. Accessed November 5, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26445108.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.