ABSTRACT

In Seoul, people of the poorest economic status live in compressed units no larger than 32 square feet, known as “sliced housing.” The majority of these residents hope for better living conditions, but they are unable to move for multiple reasons. This is an interwoven sociological issue that requires intervention proposals that improve the physical and mental wellbeing of the people in these housing situations. This thesis demonstrates possible architectural interventions that will enhance the quality of life and support systems within Seoul’s “sliced housing” villages.

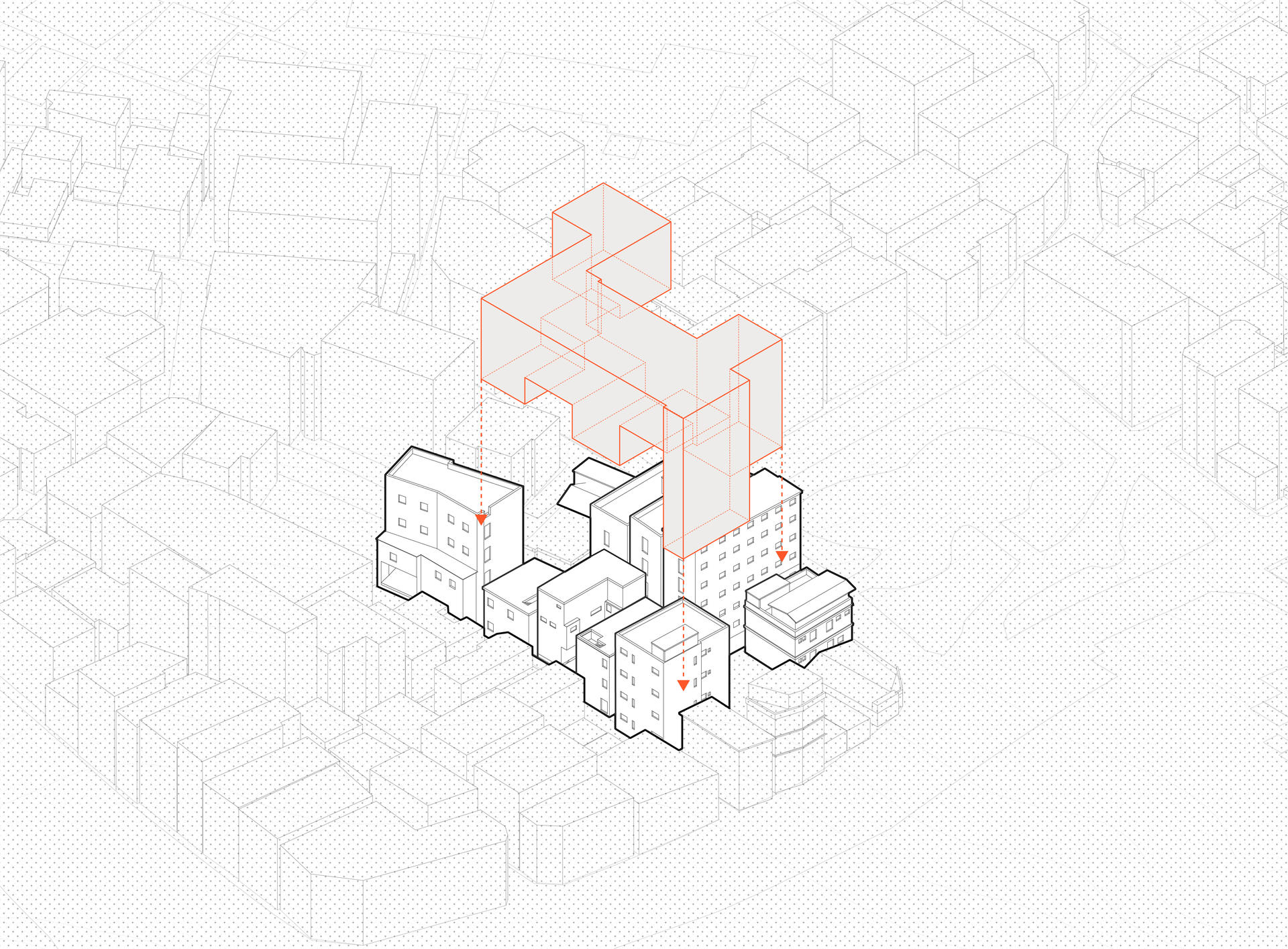

Other urban villages in Seoul in similar states of degradation have been destroyed, with districts of collective housings as a planned replacement. Though these districts intend to absorb the displaced residents, they still need to leave for several years before a new home is ready. An alternative way to renovate the area is needed that doesn’t upend the lives of the community.

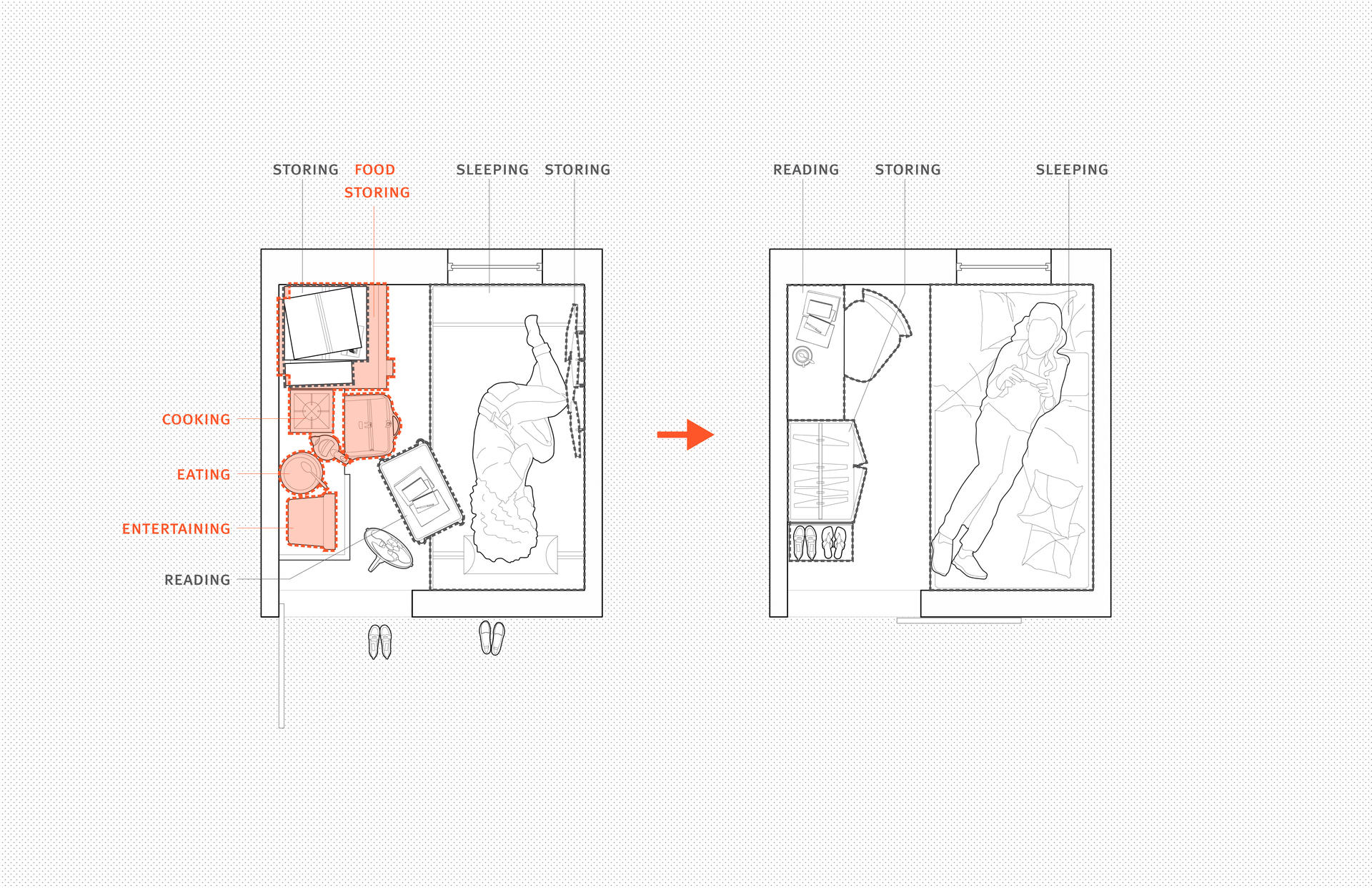

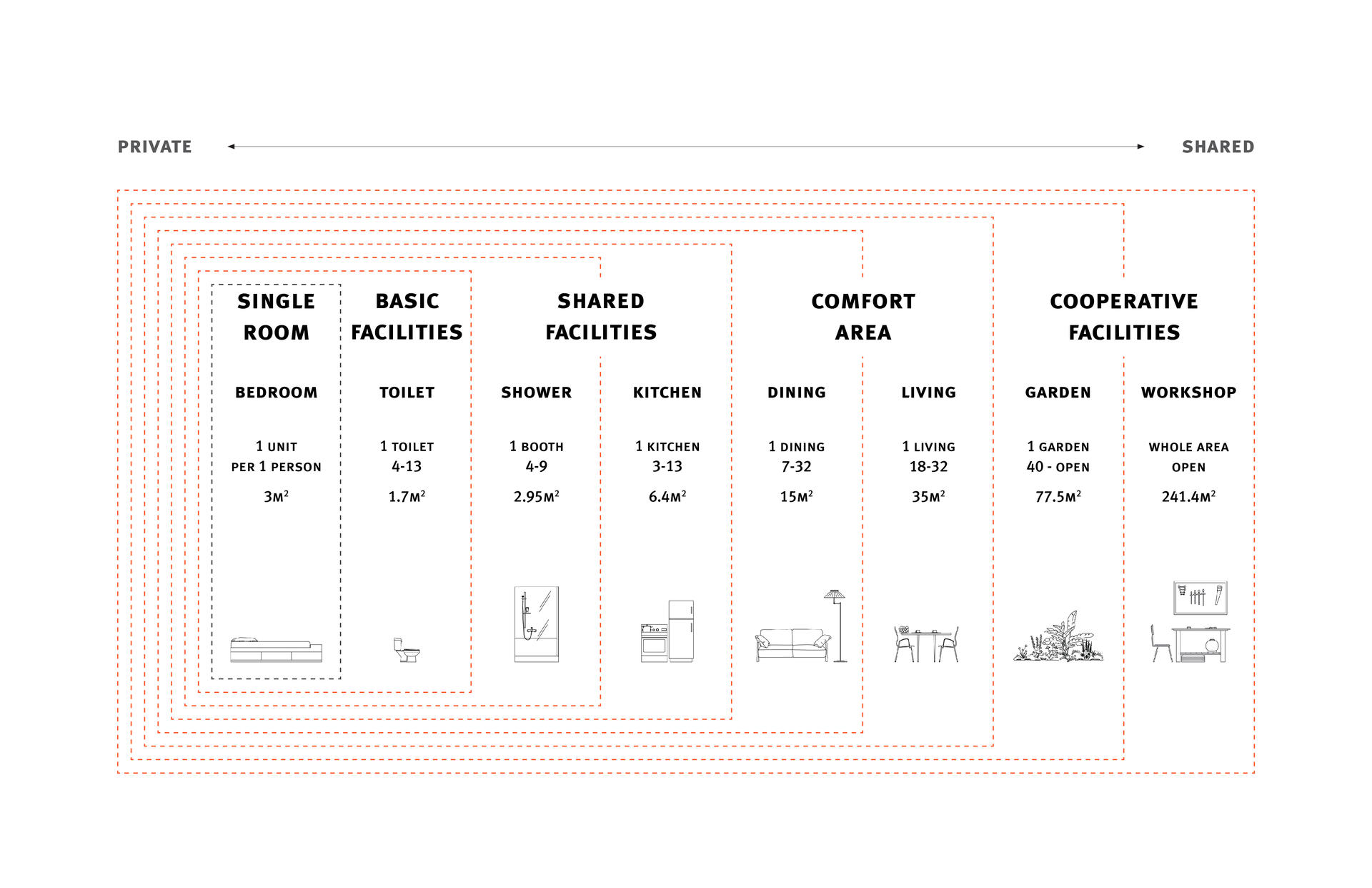

An existing single sliced housing unit holds multiple functions; sleeping, cooking, eating, resting, studying, storing. This thesis explores ways to expand shared facilities to the community within the tight context. Then overlapping activities will be spread out to the new space, leaving each new sliced unit, which is technically a small room, only for sleeping.

In addition to improvements in individual living standards, they also encourage community contact between residents. Though the city government and many charities provide resources to the community, they lack easy access. The proposal brings those facilities into the same block, enhancing a kin connection.

SLICED ROOM

“JJok-bahng” originally referred to a small room at the corner of a house. However, the term has changed in meaning to an extremely tiny room that could hardly fit one or two people which is rented to the poor. Here in this thesis, “jjok-bahng” is translated into “sliced room” referring to the current day definition.

There is not a single integrated definition of sliced rooms among charitable institutions. The common requirements could be found that are agreed with. The size of a room is less than 3m2. It is usually in an illegal accommodation facility that is rented without deposit but run by daily or monthly payment. The residents of those rooms are the poorest of the poor who do not have jobs. Even if they have jobs, they are unstable and temporary. Mostly, they are alone without family situated in the elder demographic pyramid and have physical restrictions. Sliced rooms are the most destitute housing. Some shelves and nails on the wall are the only furniture in those rooms. Showers and toilets are shared in the building, but they are hardly in usable condition. Some buildings do not have the space to cook. Rare common kitchens are as small as 4m2 for six people. This typology of dwelling does not meet the minimum requirement of residential architecture, so the government does not count these rooms in housing statistics.

Image

▲ Inside a sliced room

Image

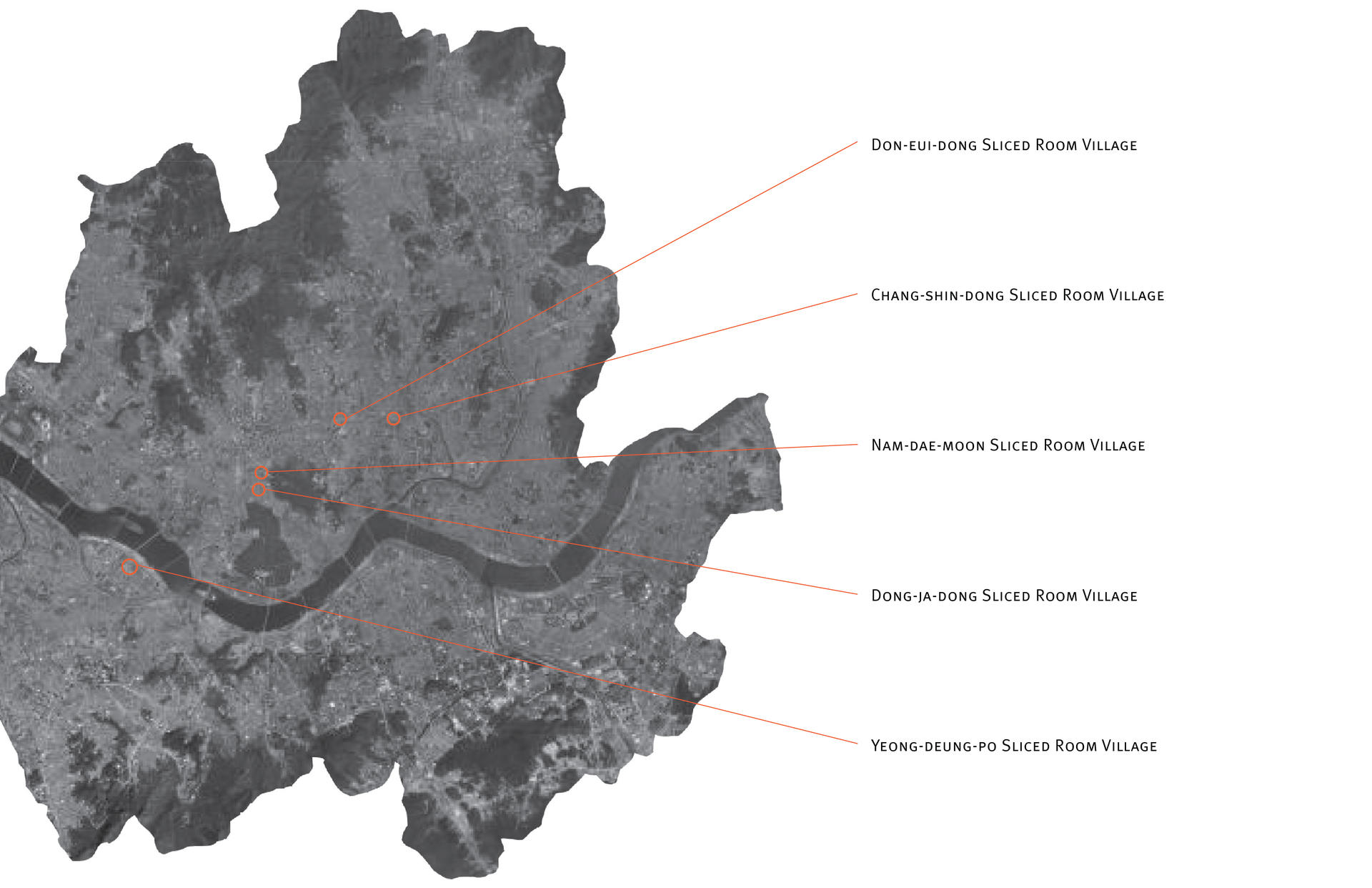

▲ Five sliced housing villages in Seoul

The term ‘sliced room’ is usually referred to as an area with these rooms clustered together. Many people are familiar with the term “Jjok-bahng-chon” which means a village of sliced rooms. It is sometimes used in general to designate poor villages even if they are not characterized by sliced rooms. According to the Seoul city government, five areas are identified as sliced room villages; Don-eui-dong, Jjok-bahng-chon, Chang-sin Jjok-bahng-chon, Nam-dae-mun Jjok-bahng-chon, Young-deung-po Jjok-bahng-chon, and Dong-ja-dong Jjok-bahng-chon. Main sliced support centers are located within 10-minute walking distance.

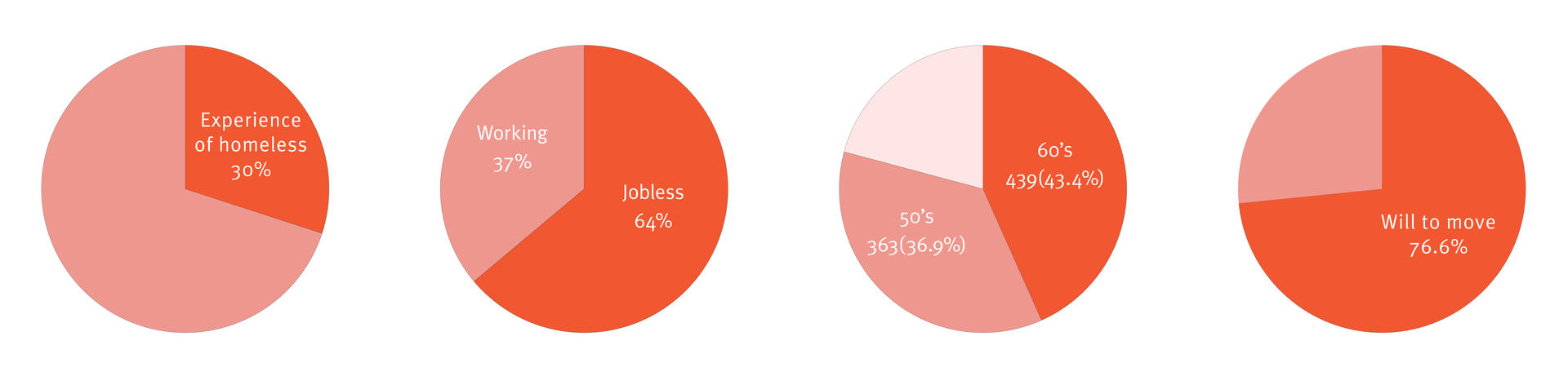

These villages are considered as the last shelter for socially vulnerable groups. 30% of the residents experienced homelessness already, and many of them still fear going back to the streets. Most of the residents rely on the basic pension from the government without any employment. The reason is that the pension cuts off when they receive official income, and most of them have passed the age of retirement. About 80% of the population are over their 50’s. They strongly desire for better conditions. Even though they can, they decide to stay within the community for social connections and support programs.

Image

PREMISE

Image

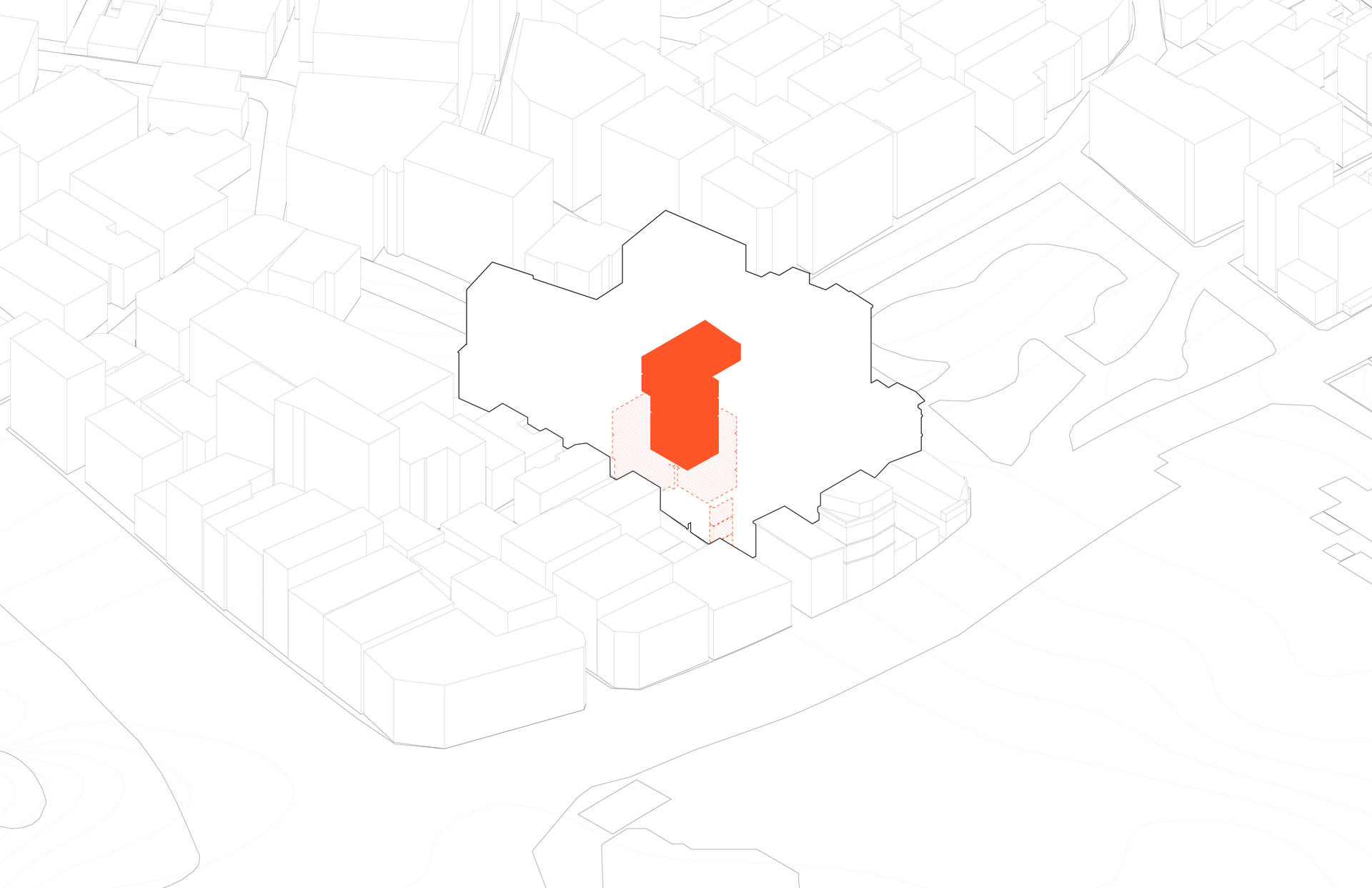

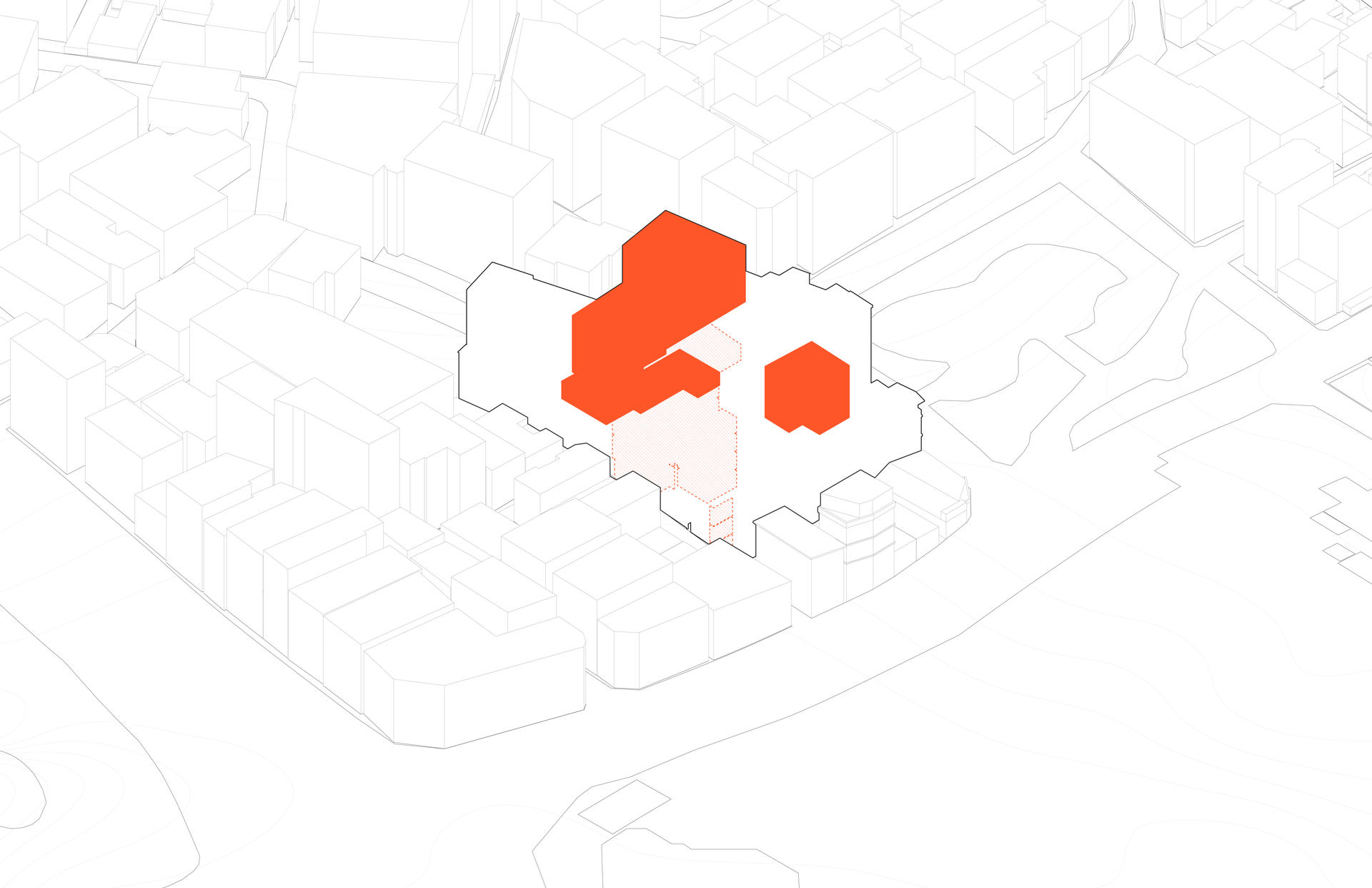

DESIGN STRATEGY

Image

Expansion for more space is the most urgent issue because too many programs overlap in a tiny space. Physical expansion could be one of the approaches, but this project won’t disrupt the existing units drastically in order to avoid evictions. Instead, each unit will be vacated by removing some programs out of the room. The new intervention leaves the most basic function in a single room. Other functions like cooking, eating, resting will be taken out of the room, so that the room can serve for more personal needs.

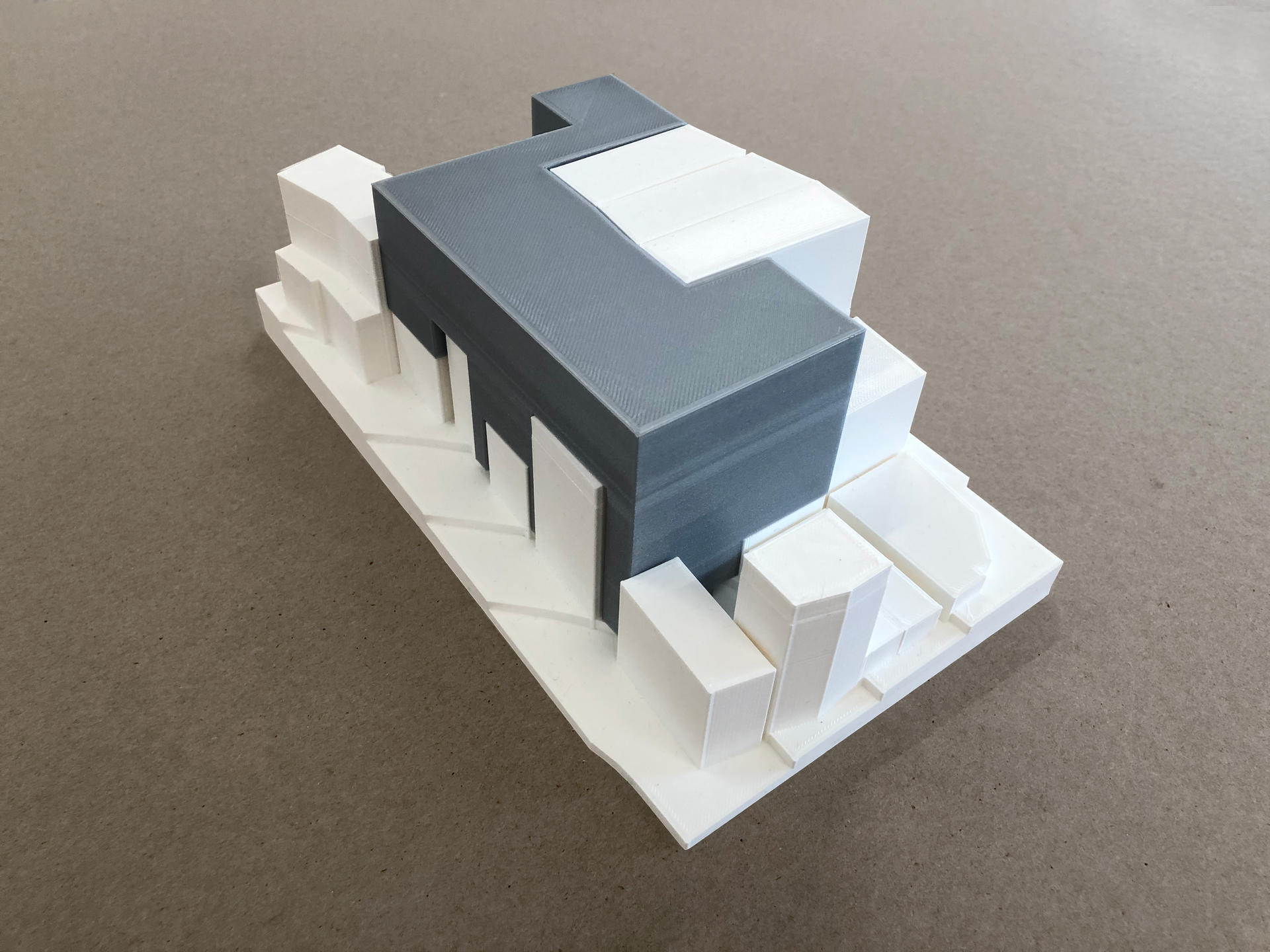

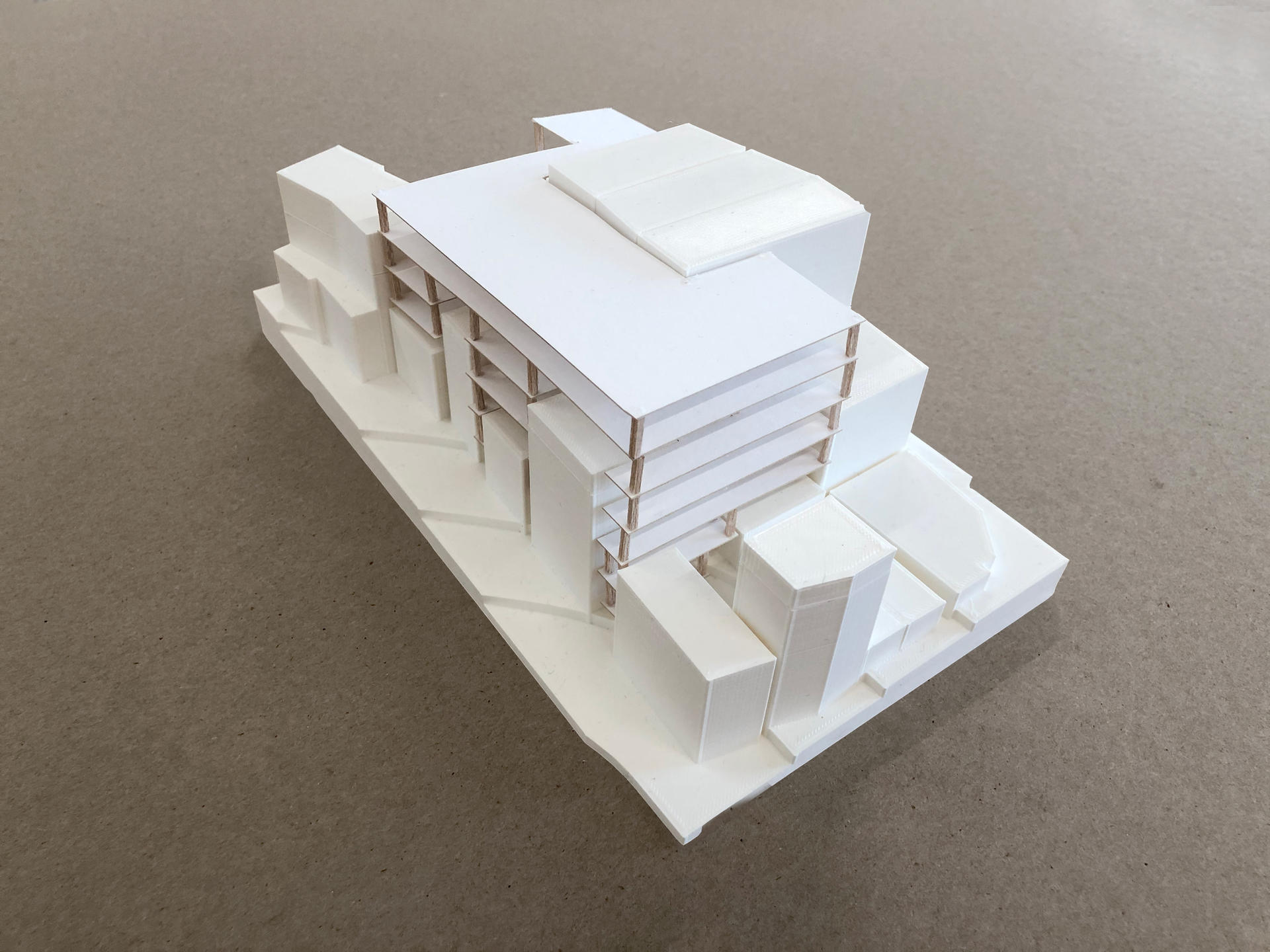

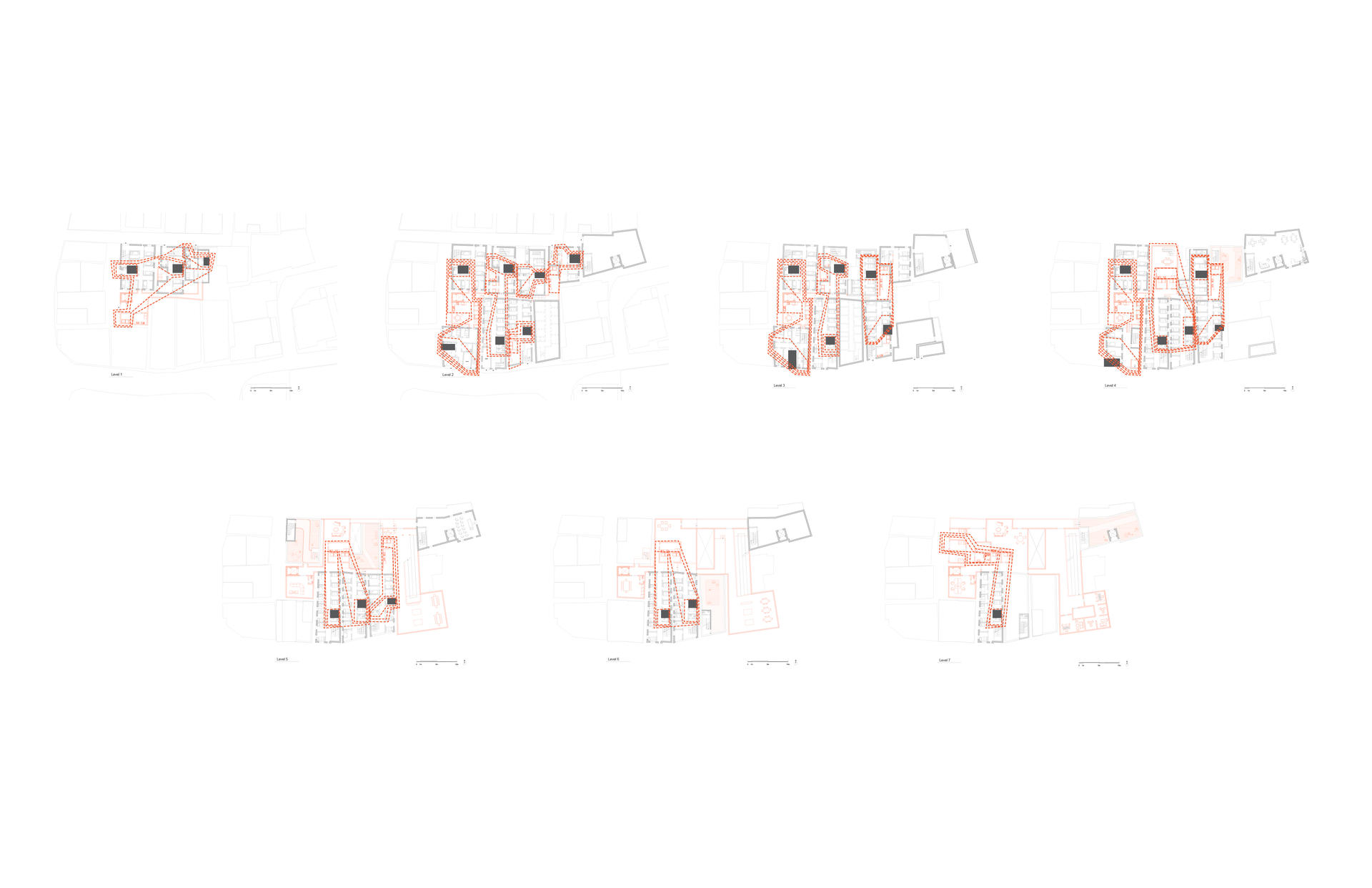

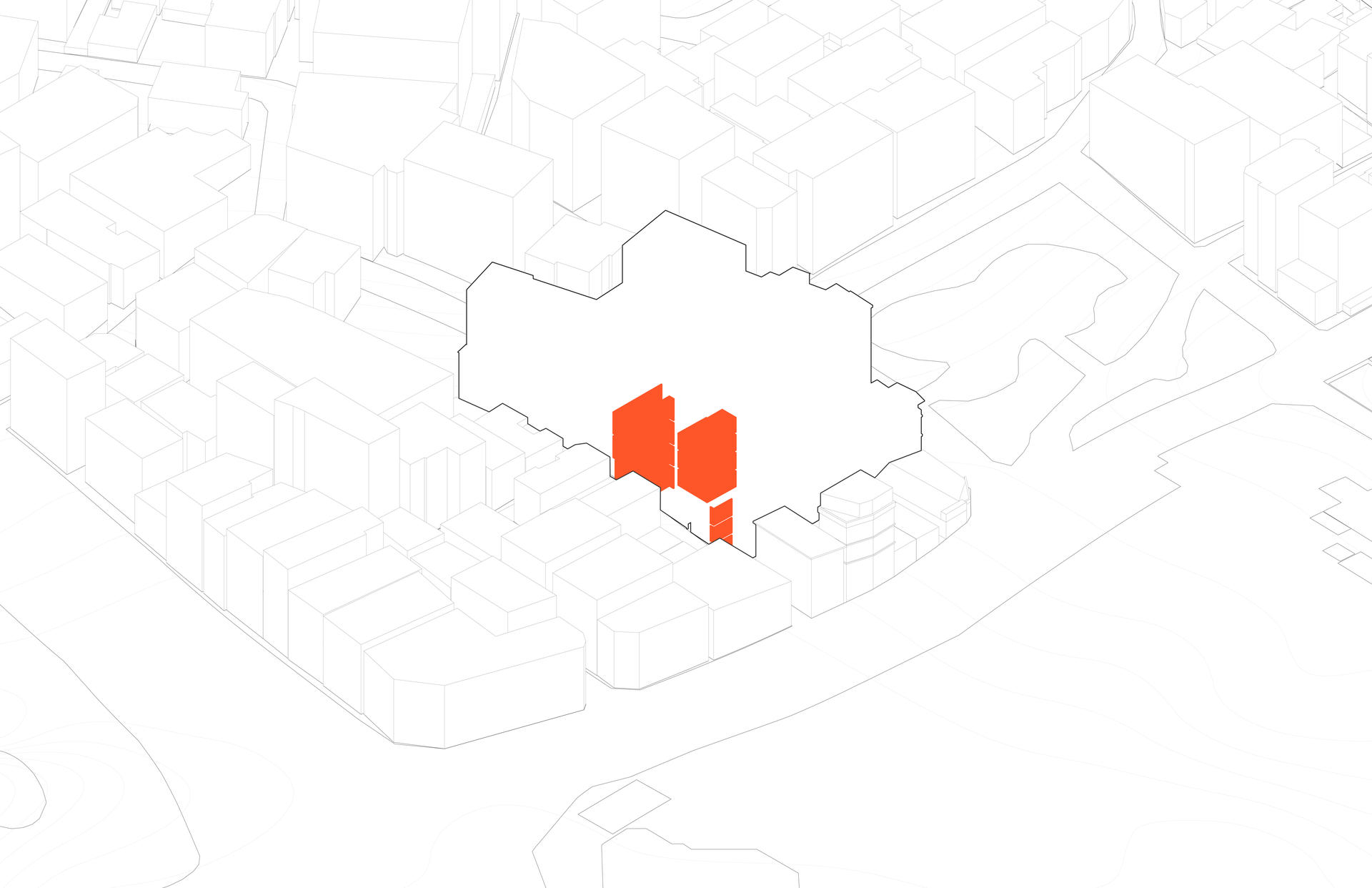

Removed programs will be located outside of the current buildings, but they have to be remained in close distance. Discovering usable land within such a condensed urban context was a challenge. The situation wouldn’t allow an open land, instead, even the small gaps between the buildings are explored for the intervention. As the existing buildings are all in different heights and shapes, there were empty spaces that could be molded out. Original living units will be unraveled over this empty space.

Image

▲ Volume study

Image

▲ Plate Study

Image

Image

The intervention aims to provide the sense of home not just rush to equipping necessities. Even though facilities can’t be privately owned, the elements of home need to be brought in. The elements of a typical home are aligned according to the necessity and frequency in order to equip more urgent facilities prior and distribute them as evenly as possible. In addition, the residents highly value the services that they can receive while staying in the site. Kin relationships and active interaction for social connection are also another important assets. Communal spaces for these purposes exist near the community, but they lack accessibility. The intervention will bring the program into the block for more active interaction.

Image

▲ Examining home bubbles for every buildings

DONG-JA-DONG SLICED COMPLEX

Image

Image

Shared facilities function as a stem of the intervention, because more necessary programs take up the even tight crevices between buildings for closer proximity to rooms. Comfort areas like dinings and living rooms sit on the upper level with more light and space. Then cooperative programs are allocated onto the existing roofs and side wings of the intervention. Existing roofs will be turned into community gardens. Edible plants will provide fresh and healthy nutrients. Also, as existing roofs are located in different levels, they will allow various environments to be created within the additional intervention.

Image

Image

Image

Image

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Lee, Jinwoo. “쪽방, 쪽방촌, 쪽방상담소(쪽방촌 실태분석을 통한 쪽방 상담소 기능 재정립 방안)[Jjokbang, Jjokbang Village, Jjokbang Counseling center(A plan to re-establish the function of the jjokbang counseling center through the analysis of the actual situation of jjokbang village)].” Seoul: 서울시 자활지원과[Seoul City Government Self Sufficient Department], 2017.

- Ha, Chun, and Hyemin Kim. “도시빈곤층의 공동체 형성 고찰-서울시 쪽방밀집지역 저렴쪽방 중심으로[A study on the formation of communities among the urban poor-Focusing on the cheap sliced rooms in the densely packed areas in Seoul].” Seoul: 서울연구원[The Seoul Institute], 2019. https://www.si.re.kr/sites/default/files/%5B%EC%9E%91%EC%9D%80%EC%97%B0…

- Ha, Sungkyu. “비주택 거주가구 주거지원 방안 마련을 위한 연구[A study to prepare a housing support plan for non-housing households].” 한국도시연구소[Korean Center for City and Environment Research], 2013.

- Kim, Sungkeun, and Changsu Ryu. “사회취약계층의 안전 실태와 개선방안 연구[Research on the safety status and improvement plan of the vulnerable social].” 한국행정연구원[Korea Institute of Public Administration], 2015. http://www.papersearch.net/thesis/article.asp?key=3536224&code=CP000000….