ABSTRACT

“In an era of both utopian high tech and unprecedented climate extremes, we are drowning in information while starving for wisdom.”1 The TEK-Way is a challenge to the long arm of globalization by looking into multi-generational wisdom, the hidden strength of every community but forgotten in the endless race for “modernization”. It inspires a new relationship of justice and coexistence by exploring and rebuilding an understanding of traditional ecological knowledge and spreading awareness of its importance and role in this era of climate change.

This thesis questions the band-aid recovery strategies of disaster mitigation through an exploration of long-term adaptation scenarios by hybridizing indigenous nature-based technologies into contemporary systems to create resilient models for disaster preparedness. Situated in India, this research explores the tribal communities of the country, the Adivasis, who are considered the most threatened by climate change to develop an understanding of their values, practices, and the power dynamics and injustices around land tenure.

Cultures have existed and respected their landscapes for thousands of years. The idea of ownership of land needs to have a paradigm shift. We, as a species, need to come to terms with the fact that the environment is not a commodity to possess by one. “Environmental degradation, increasing social conflicts, and the loss of harmonious human-nature relationships, local identity, and historical context become significant topics of concern for the future.”2 Landscape Architects have the ability to develop and envision a more inclusive response for the future and nurture resilient communities. The TEK-Way unshackles and empowers the Adivasi communities by acknowledging their rights over land, spreading awareness, and respecting their practices and skills, which could be the future of climate-resilient infrastructures.

What is Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Why is it important?

Forests have become pastures for earthmovers and coastlines the barns of the real estate lobby. In the era of the Anthropocene, the devastation humans have caused to the ecosystem is irrefutable. With human populations increasing, natural resources are depleting, environments are degrading, and identities are being lost through globalization. Yet, we keep distancing ourselves from the natural systems and lean on new technologies, disrupting the environment and inviting crises.

Now, in the era of climate change and unforeseen catastrophes, we realize that resilience and our survival depend on a thriving environment. Therefore, as designers trying to tackle these challenges, we need to focus on integrating unacknowledged nature-based technologies with current systems to develop a resilient future.

Indigenous communities were developing and working with these traditional technologies from thousands of years ago, also called by other names including Indigenous Knowledge or Native Science Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is a cumulative body of multigenerational knowledge, practices and beliefs handed down through songs, stories and everyday life. They are the foundational systems with which these populations operate. These systems are sustainable, resilient, and is born out of nature. They grow stronger over time, building a symbiotic relationship between species. They do not exploit resources, instead sustain it.

But with the inequitable impacts of transformations and issues pertaining to climate change, global warming, rising sea level, this knowledge and the communities already marginalized are on the verge of extinction.

“Our global survival is dependent upon our thinking shifting from ‘survival of the fittest’ to ‘survival of the most symbiotic’ as a critical first step."1

Image

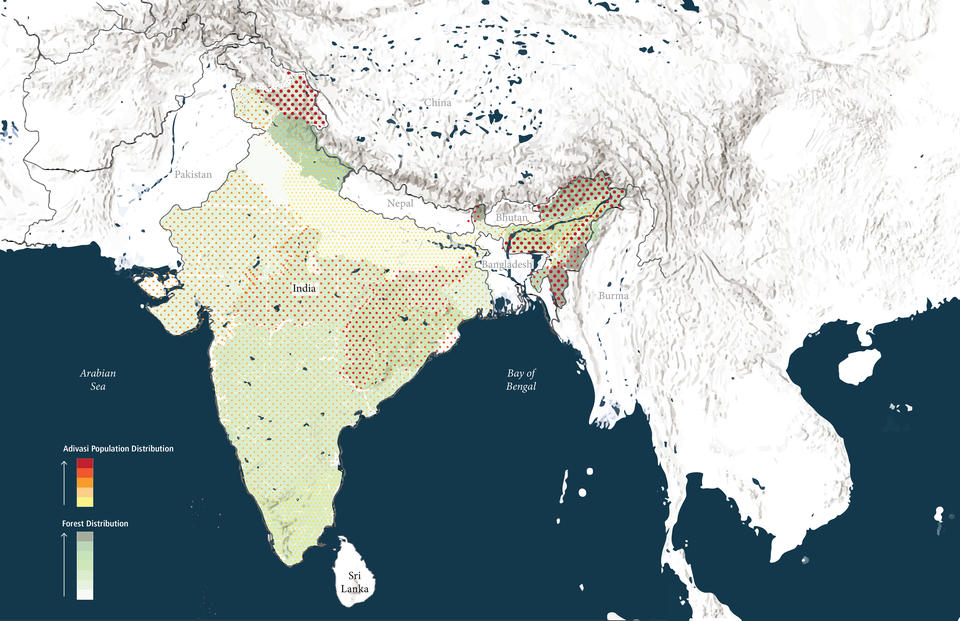

Tribal communities in India are called Adivasis - Adi meaning “first” and Vasi meaning Dweller and hence, are believed to be the first inhabitants of India.

They are India’s indigenous people and are geographically dispersed unevenly throughout the country but are essentially found in pockets mainly the forested, hilly, and mountainous areas.

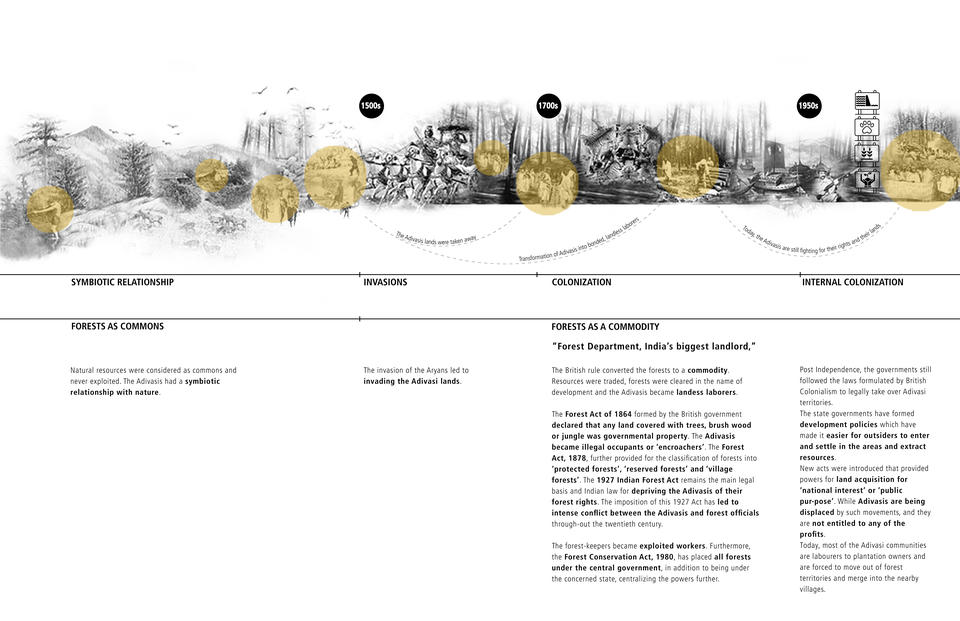

The Adivasi presence in India is thought to pre-date that of the dominant Aryan population, and their distinct identity has many aspects: language, religion, a profound bond linking the individual to the community and to nature, minimal dependence on money and markets, a tradition of community-level self-government, and egalitarian culture that rejects the rigid social hierarchy of the Hindu caste system.

Forest plays an essential role in the whole life cycle of the Adivasis. 'They live in a symbiotic relationship with nature. This has been their way of life for generations, and this is the life they enjoy and know how to lead—and hence 89.9 percent of them still live in or near the forests,' even today. However, globalization, liberalization, and privatization have forced them to abandon their land, territory, and resources. For decades, they have been struggling to survive.

Forests provide the Adivasis their essential livelihood resources, like food and shelter, and acts as their support system in terms of identity, culture, tradition, spirituality, autonomy, and social security.

However, they do not merely utilize forests for their needs; instead, they also help conserve it through various nature-based traditional practices that support the forests thrive and be resilient to any outside forces.

Today, the Adivasis traditional homelands have been taken away in the name of industrialization, tourism, plantation, mineral exploitation, developments, and nature & wildlife parks. This ‘internal colonization’ combined with globalization forces has forced the displacement and alienation of Adivasis from their land, territory and resources. They are pushed out of the forests to serve the corporate interest, resulting in resourcelessness, landlessness and impoverishment of the community.

Geographical Context

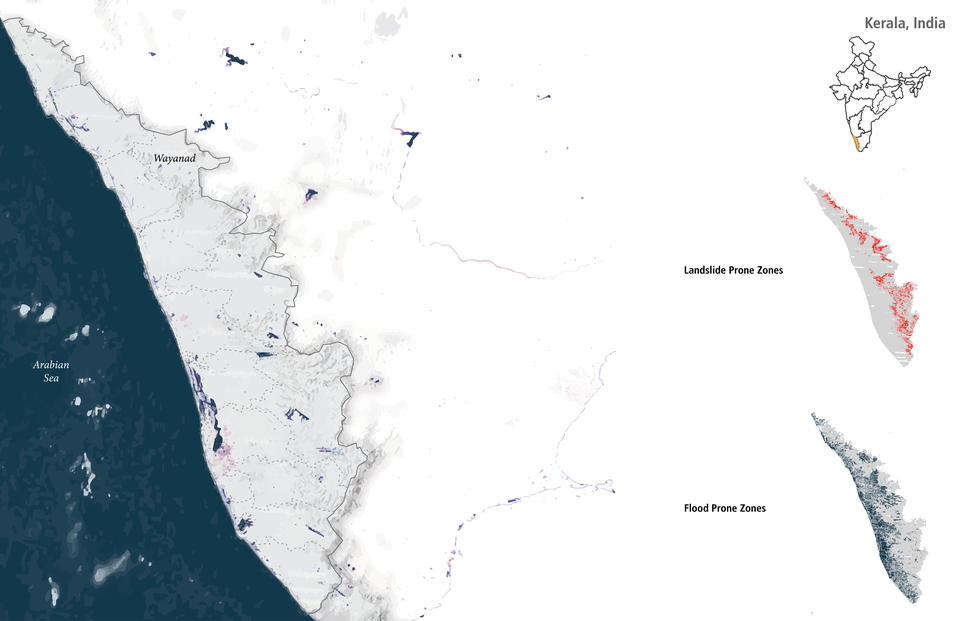

Kerala is in the southern peninsula of India, sandwiched between the Arabian Sea and the mountain ranges of the Western Ghats. Home to numerous rivers, lakes, backwaters, and estuaries, Kerala is positioned in close proximity to the sea. The state is also highly vulnerable to natural disasters like floods and landslides, severely impacting the state’s vulnerable populations.

In the years 2018 and 2019, during the monsoon seasons, Kerala witnessed one of the worst and devastating floods due to massive rainfall. The impact of rain varied across the state. The hilly and mountainous districts experienced severe landslides, while the low-lying areas faced massive floods leaving the entire region with grave repercussions.

Wayanad, a district in Northern Kerala, witnessed a heavy-handed round of these floods and landslides. These disasters though naturally triggered as a consequence of climate change they are also human-made.

All the district villages were affected. The losses endured in the disaster were immense, with a considerable loss of lives, agriculture, livestock, and significant damage to the houses, leaving most at-risk populations landless.

THE TEK-WAY STRATEGIES

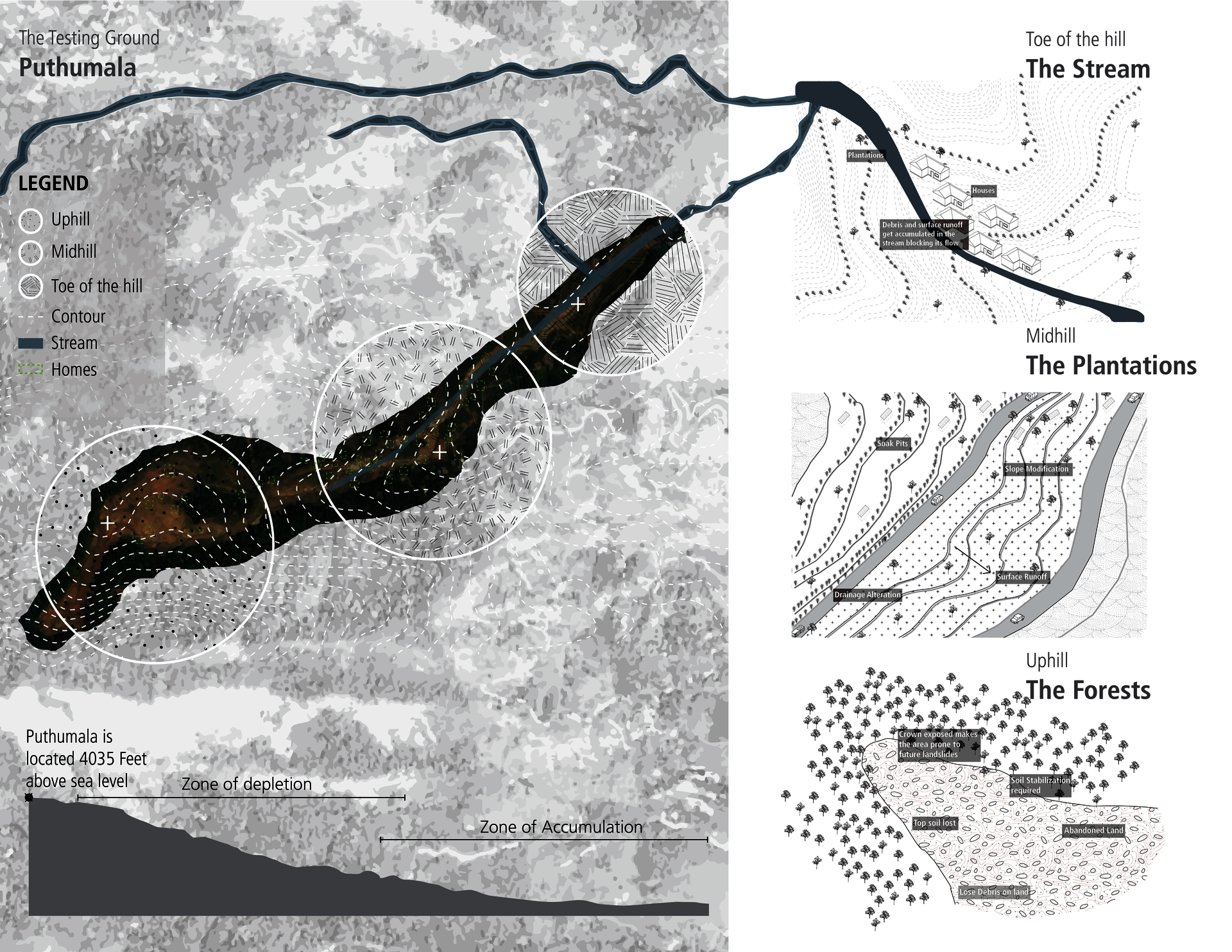

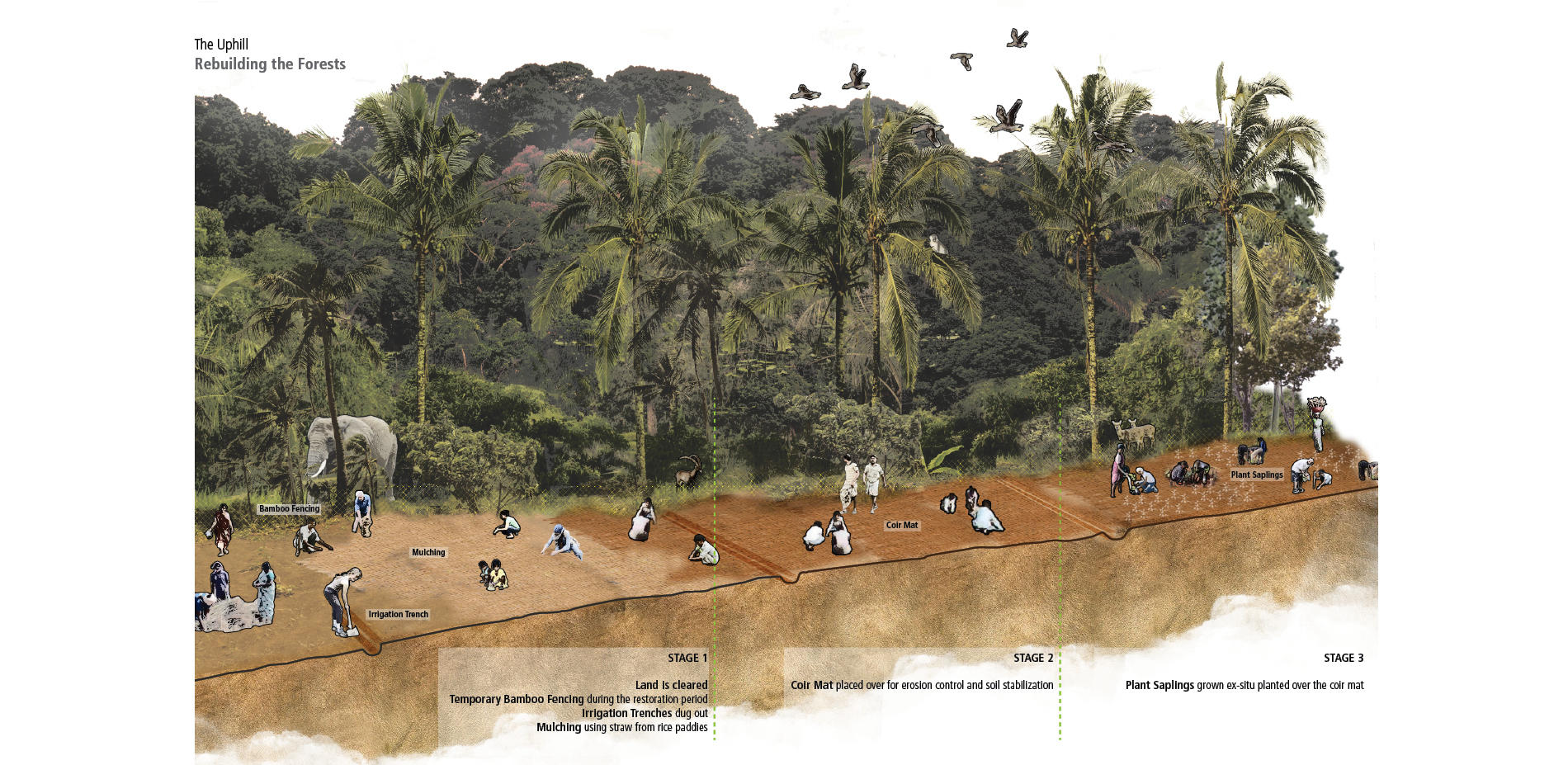

The TEK-Way envisions a system that can tackle issues in this Landscape Of Conflicts by restoring existing abandoned landslide hit sites to life. This process aims to deal with issues related to land, water, and people in order to understand how these systems could be applied to preparedness and hence become models of resilience catering to the surrounding landscapes.

Image

Image

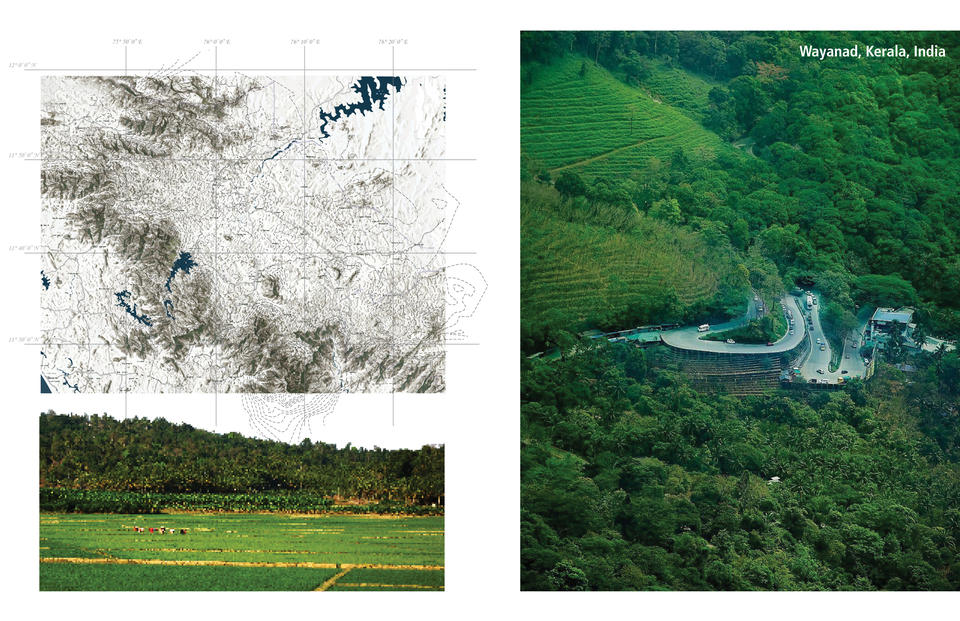

▲ Post the landslide, the ground has been left abandoned and could be leading to landslides in the future. The land currently has debris all over that gets accumulated in the stream, blocking the room for water. Hence, an effort needs to be taken to clear the land, stabilize it, and restore it.

Image

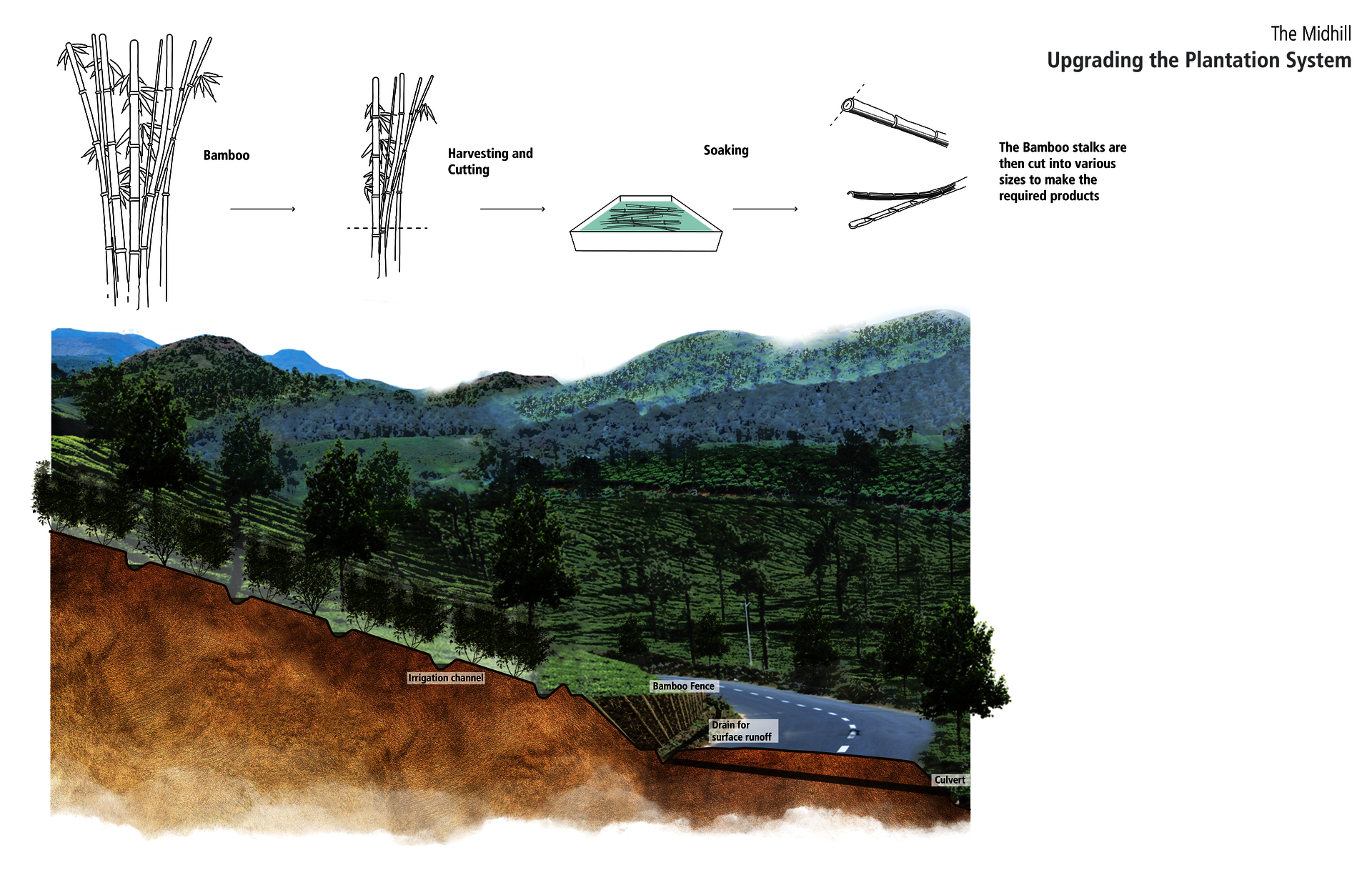

▲ The site is home to numerous tea plantations and houses constructed within the active flood plain; it was observed that plenty of rainwater was running over the slopes during the landslide event due to lack of proper drainage. There is a necessity for hill trenches/ irrigation channels to allow surface runoff to be suitably channelized.

The plantations replace the natural vegetation, modification of slope is noticed, and dug-up soak pits were constructed along the plantations for recharging groundwater and domestic water supply, thereby obliterating the natural course of drainages in the area.

Image

Image

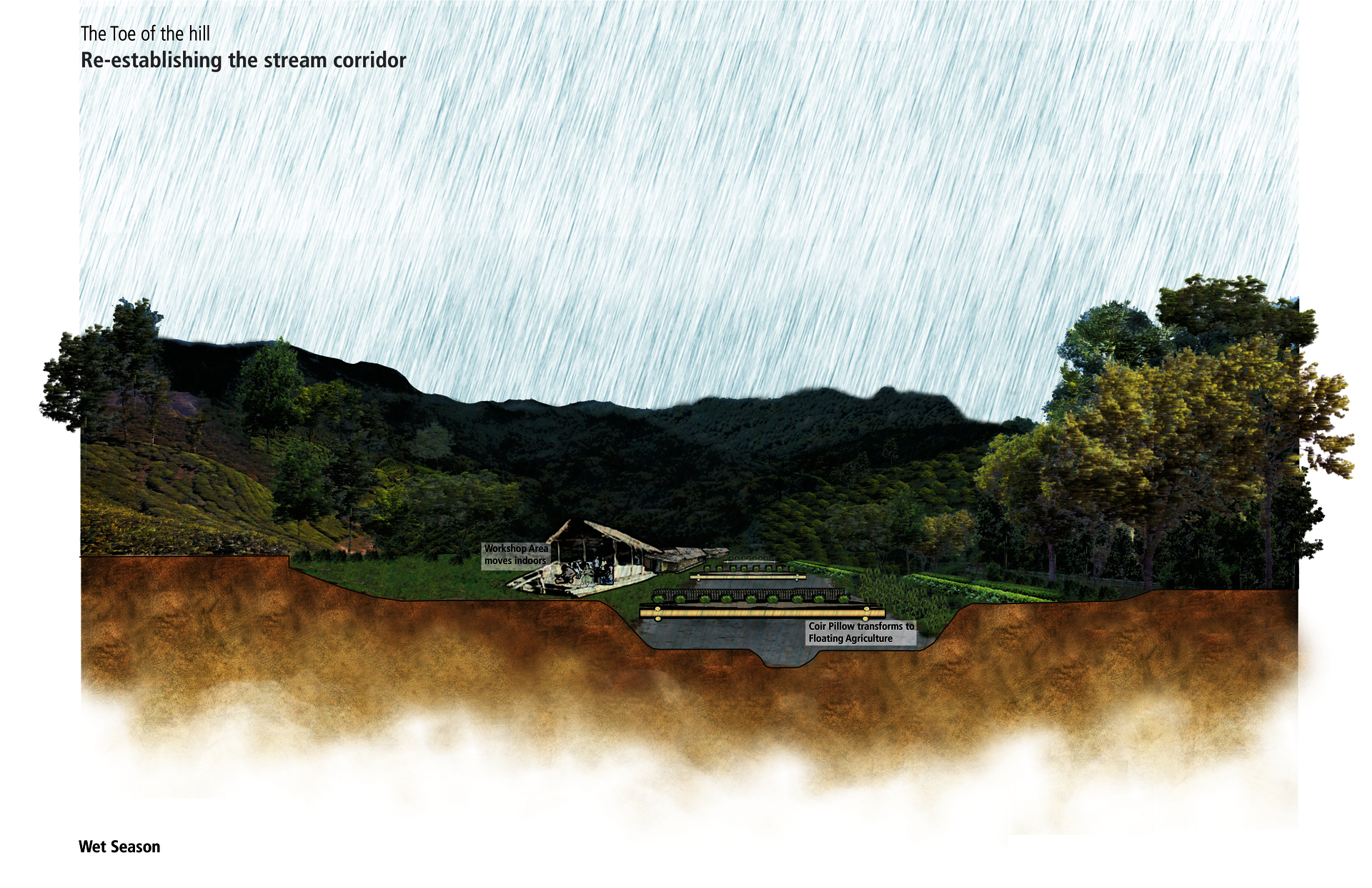

▲ Human developmental interventions have obstructed the runoff water flowing through the stream. The debris from the landslide and surface runoff is accumulated in the stream, blocking it and causing floods during adverse conditions

There is a requirement to reestablish the stream corridor, provide room for water, and live with it.

MATERIAL STUDIES

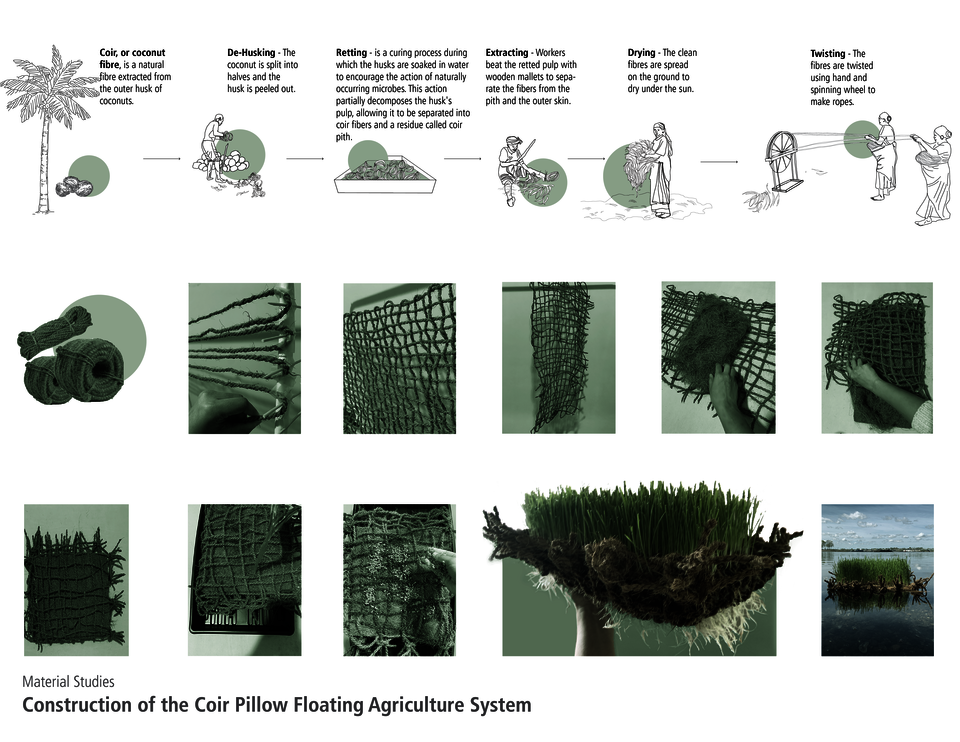

▲ To understand the water-holding properties of the material coir, an experiment was conducted by building a prototype of the coir pillow agriculture system using coir ropes, coconut husk, and wheatgrass seeds. The floating ability of the model was checked and tested on a waterbody. The experiment also involved studying coconut husk as an alternative to the soil in this system.

-

The coir ropes are weaved around a framework and interwoven to make a mat.

-

The mat is filled with coconut husk, which acts as a growing medium for plants. The mat is then tied on the ends and made into a pillow-like structure.

-

The coir pillow is soaked in water, and wheatgrass seeds were sown over it. The seeds sprouted and was fully grown by a week.

The final prototype model was let to float on a waterbody to test its floating ability.

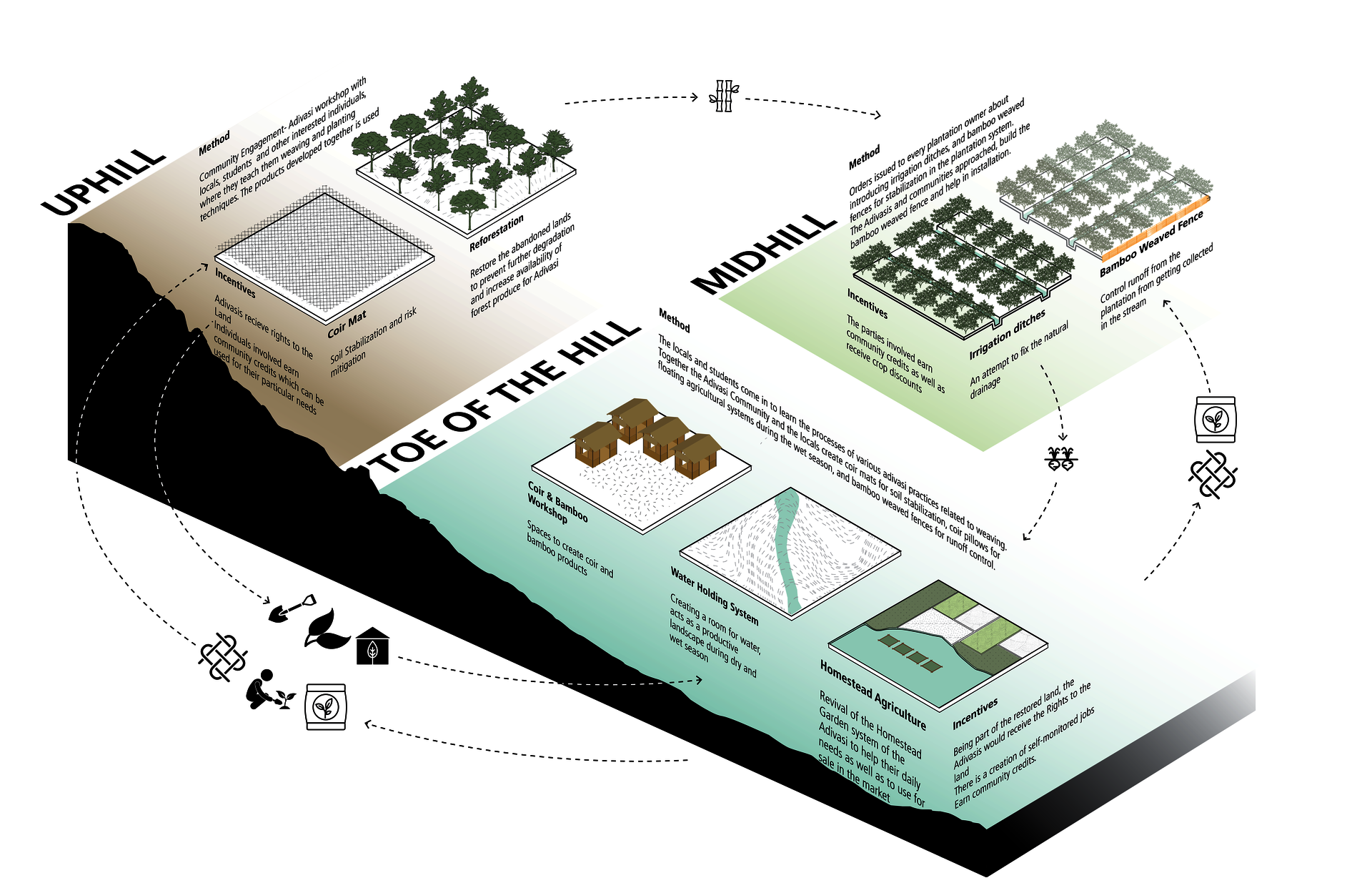

THE TEK-WAY SYSTEM

Image

▲ The three zones act as a system that provides for each other and help restore the land as well as spread awareness on traditional practices, and develop a sense of respect for it while encouraging community empowerment and economic development.

A GROWING SYSTEM

Living in the era of climate change and unforeseen catastrophes, today, designers recognize that resilience and survival of species are crucial to a thriving environment, yet this seems to be a distant utopia in practice.

Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge and practices are living examples of resilient thinking.

However, these communities are at the forefront of climate change as they face the challenge of modern-day colonialism through the imposition of the newer, “more advanced” systems and the homogenizing of these techniques as “primitive.”

Therefore, it is essential to look into this untapped knowledge towards what we call-a resilient design.

The TEK-Way is an attempt at demonstrating how imbibing Traditional Ecological Knowledge can aid in creating adaptive communities in the face of climate change and strengthen and empower them.

The idea of this project is to spread awareness on TEK through a three-step process:

- Pilot restoration project at Puthumala through the lens of Land, Water, and People.

- The restoration process is replicated in other abandoned sites.

- This knowledge and model of resilience is made available to other citizens through a learning process with the Adivasis. It is then implemented in other areas in the landscape, making it resilient to unforeseen catastrophes that could occur.

ENDNOTES

- Watson, Julia. Lo-Tek: Design by Radical Indigenism. Taschen, 2020.

- Han, F. (2016). Connecting humans and nature for an ideal future. Retrieved May, 2021, from https://www.lafoundation.org/resources/2016/07/declaration-feng-han &…;