ABSTRACT

This thesis explores the theoretical and practical relationship between mobility justice and social capital. A literature review establishes the theoretical relationship through an overview of history and policy. The relationship is then explored through a case study of Strawberry Mansion and Kensington neighborhoods in Philadelphia. These sections are then connected by considering how they are both impacted by the larger system of capitalism. The real-world example of gentrification is given for how all these elements interact and affect each other, and the practical relationship between mobility justice and social capital is established. Finally, policy implementations and paths for possible future research are recommended.

Research Questions

What is mobility justice? What is social capital? How are these concepts related and what do they look like in the real world? These are the fundamental questions that my thesis set out to explain and explore. Through the process, I learned about the movement of people, both currently and throughout history, and the complex ways they intersect with social factors and changes.

Mobility Justice and Social Capital

Mobility in its simplest definition is the movement of people and resources whether that is through transportation such as cars or natural resources like the flow of a river. Mobility of people, goods, and resources is a crucial part of our daily lives. While people may have traveled less over the past year, the mobility of packages and necessities such as groceries has become even more essential. However, like almost all systems, mobility is not inherently equitable. Within the realm of people, transportation such as cars are the dominant form of mobility, but they are only one factor that shapes people’s mobility. Issues such as race, income, and gender often shape the way people choose to move as much as access to cars and public transportation, yet they go largely unexamined in the field. As a result, mobility justice tries to fill the gap by taking intersectionality and scale into consideration. It centers around the movement of people, objects, animals, and resources across spaces whether it be on a local or global scale (Sheller 2018).

The other major theory of this thesis is social capital. Social capital is a theory which attempts to quantify the value individuals gain from social organizations and interactions. My thesis uses a hybrid definition of social capital that builds off the work of scholars Robert Putnam and Pierre Bourdieu. This definition is that social capital can lead to social bonds and communities that are beneficial to individuals socially, but they can also result in financial benefits and connections. As a result, social capital and its benefits can be unequally distributed to people who have access to high-powered individuals and organizations. By using this hybrid definition my thesis seeks a more nuanced understanding of social capital.

So how are these theories of mobility justice and social capital related? There are similarities in how people access mobility justice and social capital, and the role they play in everyday life. Both fields are greatly impacted by social inequities. Those who are unable to be mobile in their daily lives due to their location, income, race, gender, or ability live in a society that expects them to be mobile but does not give them the help or tools to do so. Similarly, those born into places of privilege and power will have more access and opportunities to build social capital and with-it economic capital than someone born into a social disadvantage. Both these forces operate in our daily lives yet the capitalist systems they occupy have made it, so they are taken for normal since they allow those in power to continue undisturbed. This reveals how issues of economics, society, geography, and policy work together to create barriers to accessing mobility and social capital. For someone who is not able to afford a car because they do not have the money, the best option for them is to get a higher-paying job. But they cannot reach that job because it is in the suburbs and not accessible by public transportation. And even if they do finally get access to a car, they may not feel safe driving it if they are black. Whenever there is a way to work around one barrier, another barrier is in place. This is no accident; it is put into place officially and unofficially by a capitalist, white supremacy system. Social capital could potentially offer an alternative by gaining capital through social connections, but the same barriers that prevent mobility are in place for social capital only they take the form of fees, unspoken rules, and privileged connections. Thus, the relationship between mobility and social capital is formed.

Image

▲ A protest at Somerset Station. In March 2021, the Somerset El Station in Kensington became a of mobility debate after Septa closed the station for two weeks. Septa cited a lack of security, broken elevators and unsanitary conditions as the reasons for closing the station. The decision was met with protests by neighborhood residents who rely on the station for mobility and argued that multiple other El stations had the same conditions but were not shut down. Photo by Kimberly Paynter.

Image

▲ The John Coltrane house located in Strawberry Mansion. The jazz musician lived in the house in the 1950s and composed important work there including his album Giant Steps. The was placed on the list of historic landmarks in 1985 but is still at risk of being destroyed. As a result, residents and musicians founded the John Coltrane House National Historic Landmark to save and restore the house. Photo by Bradley Maule.

Image

▲ A photo taken underneath the El in Kensington circa 1970. Photo by Edward Carlin

Image

▲ A photo taken underneath the El in Kensington in 2017. Photo by Jared Whalen.

Case Study

Once the theories of mobility justice and social capital, and their theoretical link was established, I was interested in understanding how it worked in the real world. As a lifelong resident of Philadelphia, I was aware of the transportation system in Philadelphia which includes buses, subways, trains, and trolleys. I was mainly interested in studying public transportation as it presents a vital but often flawed form of mobility. Philadelphia is also one of the country’s oldest cities meaning it has a multitude of histories, cultures, and organizations all of which affect social capital. In my case study, I specifically studied two neighborhoods in North Philadelphia: Strawberry Mansion (SM) and Kensington. I knew that the city was too big to look at all its neighborhoods and that by focusing on two neighborhoods I could get more detailed results about if there was a relationship between mobility justice and social capital. I chose strawberry mansion and Kensington as my neighborhoods of study because they represent larger trends in Philadelphia, both historically and currently. Throughout the twentieth century, these neighborhoods saw the effects of deindustrialization, suburbanization, and changing racial populations. Today they are struggling with changes due to gentrification and the opioid crisis. They also both are neighborhoods with sites of public transportation and social capital, meaning that data on both variables can be collected. To do this I collected qualitative data from websites, archives, blogs, and census records to understand the history, population, and mobility, and social capital makeup of these neighborhoods.

Strawberry Mansion is a neighborhood in North Philadelphia located near a large city park called Fairmount Park. Due to suburbanization in the fifties and sixties, Strawberry Mansion changed from a mostly middle-class Jewish neighborhood to a lower-income, Black population which continues to be the case today. In terms of mobility, large percentages of the population depend on public transportation for commuting to and from work. Strawberry Mansion is served by the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, or Septa, which provides public transportation to the entire Philadelphia region. Using Septa’s website, I was able to determine what transportation runs in the area and with what frequency. In terms of buses 8 routes run through the neighborhood: the 3, 7, 32, 39, 48, 49, 54, and 61 buses (Septa n.d.). The 7, 39, and 54 buses run every 60 minutes, while the 61, 49, 32 buses run every 30 minutes (Septa n.d.). The 3 and 48 bus run every 15 minutes (Septa n.d.). While there are multiple bus lines, only two out of the eight run at a high-frequency rate of 15 minutes (Septa n.d.). All the other buses require a wait of 30 to 60 minutes (Septa n.d.). This gives riders low flexibility in terms of timing if unexpected problems occur. In terms of social capital, SM has a strong history and current culture of art. From the jazz musician John Coltrane who lived in the neighborhood in the 1950s, to an art group that is working to bring historical and cultural awareness to the neighborhood. These groups help build social capital by growing a sense of community, bonding, and investment. Additionally, SM has a Community Development Corporation (CDC) which helps residents with organizing finances, buying houses, and offering grocery vouchers among other services. This CDC helps to build social capital by providing residents with financial empowerment which increases their access to other social capital and builds ties with other residents.

Kensington, the other neighborhood of study, was historically an important site of industry in the city producing textiles, tools, and other goods. In the 1980s when industrialization caused many factories to move overseas, Kensington was left without a source of income and many abandoned factories and houses. The neighborhood changed from a majority white, middle-income neighborhood to a lower-income neighborhood with most of its residents being Black or Latino. Currently, Kensington is also suffering as the epicenter of Philadelphia’s opioid crisis, which has a large effect on the environment of the neighborhood, as well as mobility and social capital. In terms of mobility, Kensington residents on public transportation are slightly lower, but still high levels in terms of commuting to work. The main form of public transport is the elevated train, or the el, which runs on a track above one of the main streets in the neighborhood. The social capital situation in Kensington is slightly different than in Strawberry Mansion. Due to the opioid epidemic, many people in the neighborhood are struggling with substance abuse disorders and experiencing homelessness. This affects social capital in two main ways: it has caused Kensington residents to feel frustrated and uninvested in the neighborhood. It has also caused sites of social capital to be built around substance abuse rehabilitation. Two rehabilitation houses, Last Stop and First Stop offer a sense of community, stability, and hope for people struggling with substance abuse. This makes these sites important for both social capital and combating the opioid crisis.

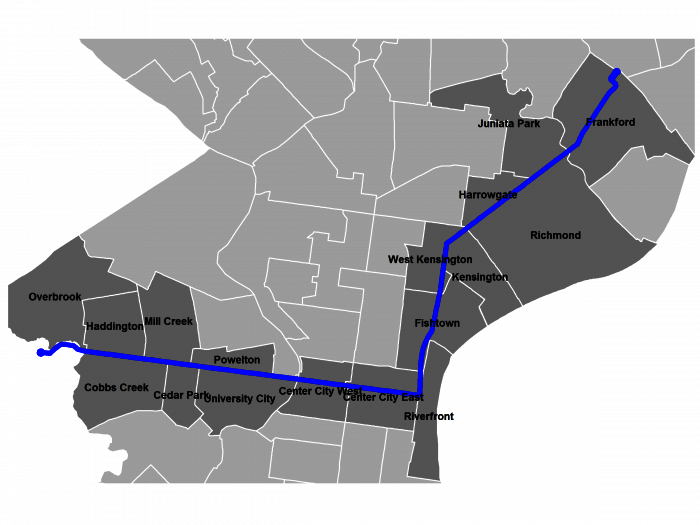

So now that mobility and social capital in this case study have been established, the question becomes how are they connected? The answer is found by considering the larger systems and environments they both exist in. If mobility justice is the ability for a person or community to control over how, when and where they move, then part of that justice is having the ability not to move. Unfortunately, this is the case for residents in both Strawberry Mansion and Kensington as the neighborhoods are gentrifying and they can no longer afford the rent or property taxes to live there. Gentrification is commonly thought of as the result of higher-class individuals moving into lower class neighborhoods. However, while individuals do play a role in gentrification, the bigger players are real estate companies that buy land in neighborhoods while it is still inexpensive and then slowly start to develop and raise living prices as individuals of classes begin to move in. Without these companies and corporations gentrification could not take place on the scale that it does. The rising cost of living in these neighborhoods is a risk to mobility justice and social capital. In Strawberry Mansion residents being forced to move could damage the various arts organizations and movements that create social capital in the neighborhood. Gentrification also poses a threat to the rehabilitation houses in Kensington, one of which has already had to move due to increased property taxes. If these houses are forced to shut down, then the neighborhood would not only lose a source of social capital but also an important tool for people dealing with substance abuse disorder. However social capital can also be a tool for combating gentrification and mobility injustice. In SM, the bonds residents have built through social capital have helped them feel more invested in their neighborhood and could help them fight gentrification. In Kensington, the recovery houses help people find sobriety could also help ease tensions with residents and businesses owners who are frustrated by the opioid epidemic. However, without a sense of community, residents may find it harder to fight against gentrification in the neighborhood.

Gentrification in Kensington

▲ A sign for Last Stop, an important source of social capital in Kensington. It may seem contradictory that a neighborhood struggling with the opioid crisis would be gentrification, but the low property values make large scale building and development inexpensive. Septa also contributes to gentrification. The map shows the areas the El train runs through broken down by neighborhood. The graph shows the extra value, or premium, on houses located in Kensington and its neighboring neighborhood Fishtown, compared to Philadelphia as a whole. Photo by Jim “Bear” Katona Jr. Map and graph by Jonathan Tannen.

Gentrification in

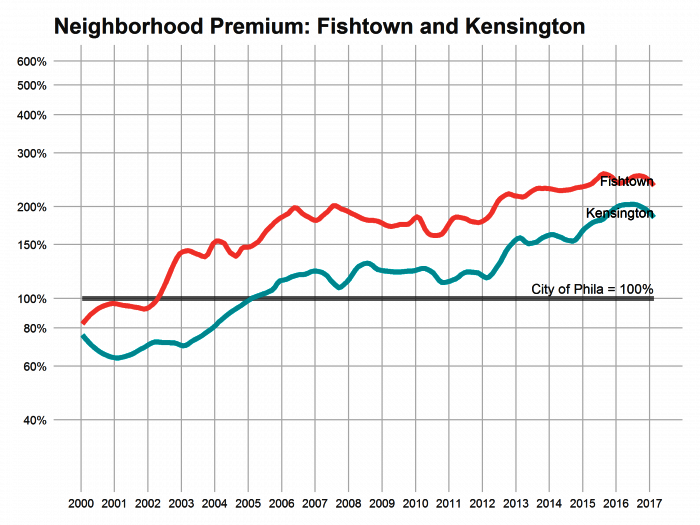

Strawberry Mansion

Image

▲ Using census data, this graph shows the median income difference between people who use cars vs. public transportation to commute to work. This illustrates the far-reaching impacts that mobility can have on other areas of life. Graph by Rebecca Fruehwald.

Image

▲ A street in Strawberry Mansion that tells the story of a changing neighborhood. Older row homes built-in working-class neighborhoods in the 20th century, stand next to the new construction of apartment buildings, a common sight in gentrifying neighborhoods. Organization such as the CDC are fighting for resident’s rights to stay in the neighborhood against the rising cost of living. Photo by Danya Henninger.

Image

▲ A sign of the times on the subway. Septa has seen large drops in ridership and income due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Service cuts are continually discussed and threaten mobility in the city. Photo by Rebecca Fruehwald

Policy Suggestions

As Philadelphia faces changes, growing inequity and increasing violence, the question becomes what policy steps can be taken to combat these issues? An important step is understanding the value of social capital and the work it is already doing. For instance, helping to build community investment and understanding, particularly in Kensington, is one policy movement the city could take to help promote mobility justice and social capital in Philadelphia. Another important step is for Septa to acknowledge the role it has played in gentrification. As shown above in the images above residency and property value along Septa routes are contributing to gentrification. Rather than let this continue, Septa should work with these communities and organizations to find ways to grow sustainably and protect mobility. Finally, Philadelphia must take steps to limit gentrification as a source of income. Many cities are now dependent on the income from the corporations, businesses and individuals that come with gentrification for daily operation. However, by doing this they are valuing the system of capitalism above Black and low-income spaces and lives. In the last year Philadelphia has discussed ways to improve racial equity, but as gentrification in the city continues it becomes clear that the systematic capitalism that causes gentrification does not allow space for equity. To protect mobility, social capital, and lives, firm policy steps must be taken to achieve justice. By working with communities, listening to ideas and taking policy steps such as the ones described above, a more equitable and just Philadelphia is possible.

ANNONTATED BIBILOGRAPHY

Carpiano, Richard M. 2005. "Toward a neighborhood resource-based theory of social capital for health: Can Bourdieu and sociology help?" Social Science and Medicine 62, no. 1 (January): 165-175. https://doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.020

Fairmount Park Conservancy. N.d. “Strawberry Mansion Short Films” Accessed December 2, 2020. https://myphillypark.org/what-we-do/arts-culture/strawberry-mansion/

Historic Strawberry Mansion. “Timeline.” Accessed December 2, 2020. http://www.historicstrawberrymansion.org/timeline/

Lubrano, Alfred. 2018. “How Kensington Got To Be The Center Of Philly’s Opioid Crisis.” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia), January 23, 2018. https://www.inquirer.com/philly/news/kensington-opioid-crisis-history-philly-heroin-20180123.html

Madej, Patricia. 2020. "Septa Shows Dire Map of Reductions." Philadelphia Inquirer [Philadelphia], 19 Aug. 2020.

Moskowitz, P.E. 2018. How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood. New York: Bold Type Books. Amazon E-Book.

Pew Charitable Trusts. 2019. “The State of 10 Cities.” Pew Charitable Trusts, December 3, 2019. www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2019/the-state-of-10-cities

Septa. N.d. “Route 3.” Accessed November 30, 2020. http://www.septa.org/maps/bus/pdf/003.pdf

Septa. N.d. “Route 39.” Accessed November 30, 2020. http://www.septa.org/maps/bus/pdf/039.pdf

Septa. N.d. “Route 60.” Accessed November 30, 2020. http://www.septa.org/maps/bus/pdf/060.pdf

Sheller, Mimi. 2018. Mobility Justice The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. New York: Verso. E-book

Strawberry Mansion Community Development Corporation. N.d. “Board Members.” Accessed November 30, 2020. http://www.strawberrymansioncdc.org/board-members/

The Why. 2019. “The Last Stop’s last stand? Why a Philly addiction recovery house is fighting to stay open.” NPR, March 11, 2019. https://whyy.org/episodes/the-last-stops-last-stand/

United States Census Bureau, American Community Survey. 2011- 2018. Means of Transportation to Work By Selected Characteristics. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=8600000US19132,19143&tid=ACSST5Y2018.S0802&hidePreview=false

Casper, Amanda. 2013. “Row Houses.” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/row-houses/

ENDNOTES

Carlin, Edward. Under the El. Photograph. Philadelphia History Museum.

http://www.philadelphiahistory.org/objects/under-the-frankford-el/.

Henninger, Danya. A Strawberry Mansion Block. Photograph. Billy Penn. December 10, 2017.

https://billypenn.com/2017/12/10/how-strawberry-mansion-residents-are-f….

Katona, Jim "Bear", Jr. Last Stop Sign. Photograph. Kensington Voice. January 30, 2019.

https://kensingtonvoice.com/en/truth-is-abundant-in-kensington/.

Maule, Bradley. John Coltrane House circa 2005. Photograph. Hidden City. https://hiddencityphila.org/

2013/03/at-coltrane-house-getting-closer-to-the-dream/.

Paynter, Kimberly. Kensington residents gathered at SEPTA's Somerset Station to protest its closure Tuesday, March 23, 2021. Photograph. WHYY. March 26, 2021. https://whyy.org/articles/

septa-to-reopen-somerset-station-after-repairs-with-a-new-police-booth-more-security/.

Tannen, Jonathan. "Neighborhood Premium: Fishtown and Kensington." Graph. Econsult Solutions Inc.

https://econsultsolutions.com/impacts-the-el-has-on-neighborhood-housin….

Tannen, Jonathan. "The El's Neighborhoods." Map. Econsult Solutions Inc.

https://econsultsolutions.com/impacts-the-el-has-on-neighborhood-housin….

Whalen, Jared. Under the El. Photograph. Billy Penn. March 27, 2017. https://billypenn.com/2017/03/

27/how-the-overworked-unstable-el-just-might-be-saving-philadelphia/.

Maule, Bradley. John Coltrane House circa 2005. Photograph. Hidden City.

https://hiddencityphila.org/2013/03/at-coltrane-house-getting-closer-to-the-dream/.

Paynter, Kimberly. Kensington residents gathered at SEPTA's Somerset Station to protest. Photograph.

WHYY. March 26, 2021.

https://whyy.org/articles/septa-to-reopen-somerset-station-after-repair….

Katona, Jim "Bear", Jr. Last Stop Sign. Photograph. Kensington Voice. January 30, 2019.

https://kensingtonvoice.com/en/truth-is-abundant-in-kensington/.

Henninger, Danya. A Strawberry Mansion Block. Photograph. Billy Penn. December 10, 2017

https://billypenn.com/2017/12/10/how-strawberry-mansion-residents-are-f….

History, Philosophy, and Social Sciences

Division of Liberal Arts

Nature, Culture and Sustainability Studies Program

Advisors:

Dr. Alero Akporiaye, Assistant Professor

Dr. Lauren Richter, Assistant Professor