Lilly Manycolors

Colonial Mapping, Heteropatriarchy and the Remaking of the World

Colonial mapping is the mechanism that male supremacists utilize in the unmaking and remaking of the Land. This unmaking and remaking simultaneously erodes the interrelationality between the Land and all inhabitants. Heteropatriarchy generates colonial mapping through an onto-epistemological scheme that works to undermine pre-existing Indigenous knowledges and relationships. This is done for the purposes of remaking the world in order to consume what male supremacists determine as a potential commodity. Male supremacy/colonialism necessitates the rape and desctruction of the Land and Indigenous people as a means of landscaping through the understanding that Indigenous people and the Land are synonymous. Colonial mapping is rooted in heteropatriarchal unmitigated greed resulting in cultural-climatic-geospatial catastrophe. Thus, genocide and ecocide are conspiratory benefactors in the capitalist enterprises of oil, water and other resource extractivist projects. Colonialism utilizes mapping to erode Planetary interrelationships and care-systems. Conversely, globally Indigenous communities have continued to disidentify with colonial ontology and sustained their own mapping practices and rotations towards care which narrate the continuous and unyielding cross-species interrelational networks. Indigneous ontologies and their subsequent mapping practices show us that colonialism can be disassembled just as it was assembled, and that there is, in fact, ample opportunity to rotate towards ontologies of care which produce mapping practices that topographically chart Planetary interrelationality.

Image

Bound thesis of Lilly Manycolors featuring a "Map of the Elements" by Manycolors' daughter Lyra Murphy-Manycolors.

Colonial Mapping of Space and Bodies

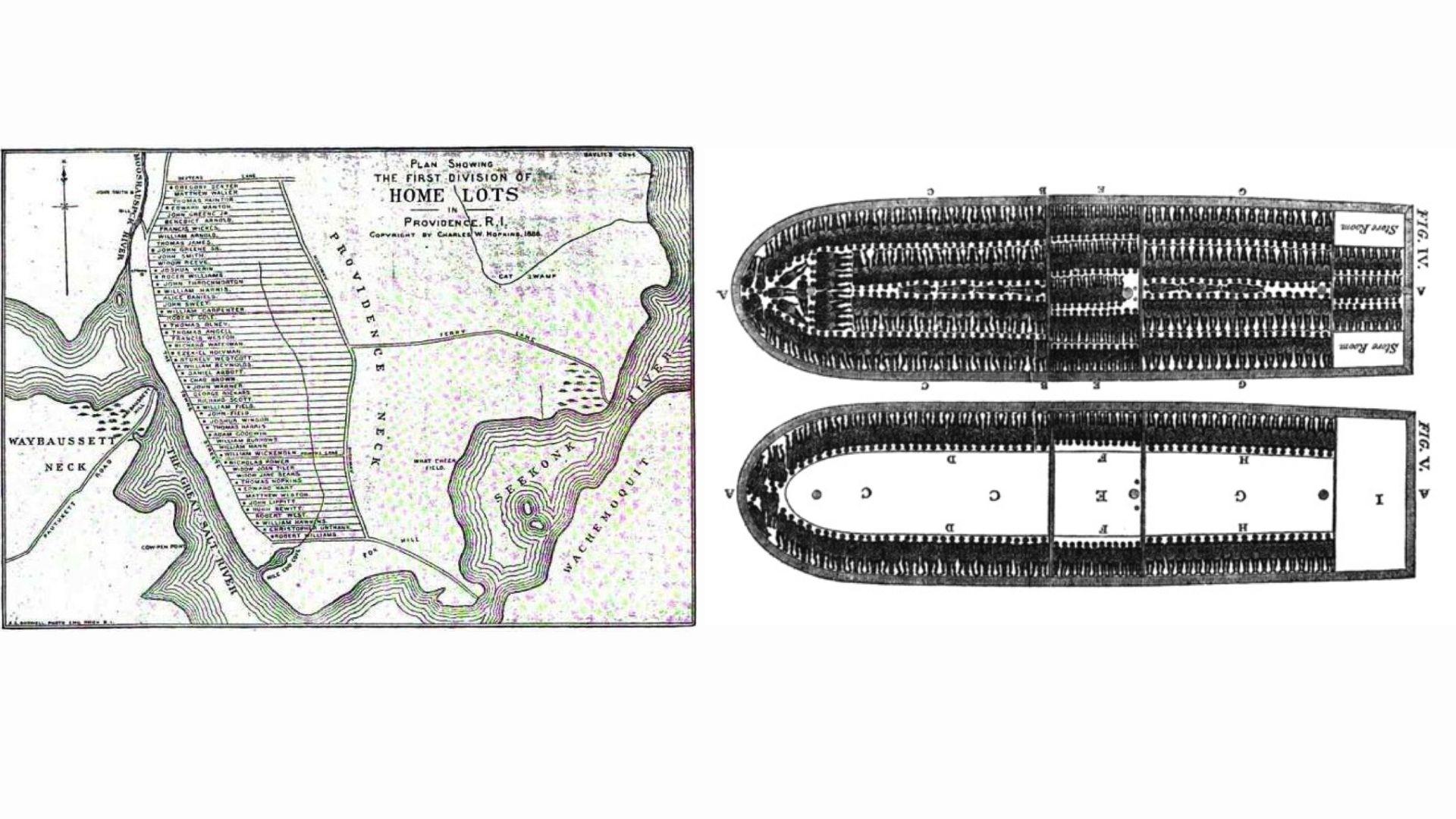

Colonial mapping’s egregious effects on the Land and people is made visible when comparing the images 1A and 1B. A comonality is visible with how Land was depicted and delineated into property, and the manner in which slave ships were designed and utilized. Colonists used similar depictions of horizontal and vertical lines to represent the spaces and bodies being commodified as clearly demonstrated by the images to the left. Image 1A is a map of the plantations in Providence, RI from the late 1800’s to early 1900’s. The plantation structure sliced the Land into elongated rectangular properties, no longer allowing for the Land’s animacy as Land-Mother. In image 1B there is a similar assignment of the slave ship’s space where Black bodies were drawn in the same fashion as the plantation property sectors. Indeed, Black bodies were thought of and engaged as property. Tiffany Lethabo King’s comments on Sylvia Wynter’s essay 1492: A New Worldview emphasize Wynter’s usage of a “‘triadic model’ (White-Native-Black) to understand the antagonisms that would bring forth the nation of the modern human and inform conquest” (King 2019: 53). The “triadic model” that both King and Wynter are speaking to is the racialization systems designed to unmake and remake bodies coded for commodification. King continues to comment on how this triadic model is echoed in Hortense Spillers’ writing Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe (1987), but it is through Wilderson’s reworking of “Spillers’s conceptualization of flesh” that we have a better understanding on “how the making of the human requires the unmaking of the Black and Native bodies into nonhuman matter” (Ibid). It is this unmaking and remaking that renders the Black and Indigenous Bodies as flesh which the colonist kneads and reshapes to its desire. Colonial mapping figuratively and literally unmakes and remakes the Land and Black bodies into capital gains. King continues to clarify that it is through the colonial onto-epistemology that “the nonhuman (slave and savage) is fleshly matter that exists outside the realm of the body and, thus, humanity” and I liken this outside realm to be where Land is located. It is this outside realm where Land and Black and Indigenous people become synonymous. Necessitated by the labor demands of male supremacy and colonial conquest, the Black body and the Indigenous body were fabricated to be subservient to the desires of the male supremacists. The Land, Indigenous body and the Black body were (continue to be) treated similarly in terms of spatial organization of products/property by the colonists/settlers (as seen in images 1A & 1B). Colonial epistemologies allow for a politic that denotes anything devoid of beingness (interrelationality) will not require humane conditions. This judicious thinking allows for the molding of “bodies” that produces such horrid environments as cotton plantations, factory labor, prisons, immigrant farm labor and innumerable or countless. Thus, these two images would naturally bear similarities since both the Land and bodies present are seen as the same entity: commodities. In a colonial reality the Land Body, the Black Body, the Indigenous Body, and the Feminized Body will always be arenas of white-patriarchal perverted ambition.

Image

Providence, Rhode Island Plantation 1902 A. Bodwell, Plan Showing The First Division of Home Lots in Providence, R. I., from State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History by Edward Field, 1902. [Public Domain] Source: Wolin, Jeremy L. “Demolition & Amnesia: Roger Williams National Memorial.” Demolition Amnesia Roger Williams National Memorial, blogs.brown.edu/investigatingasite/2017/05/05/roger-williams/ + Trans-Atlantic Slave Ship 1790. Diagram of a slave ship from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, 1790-1 [Public Domain]

Reshaping the Land and Seas

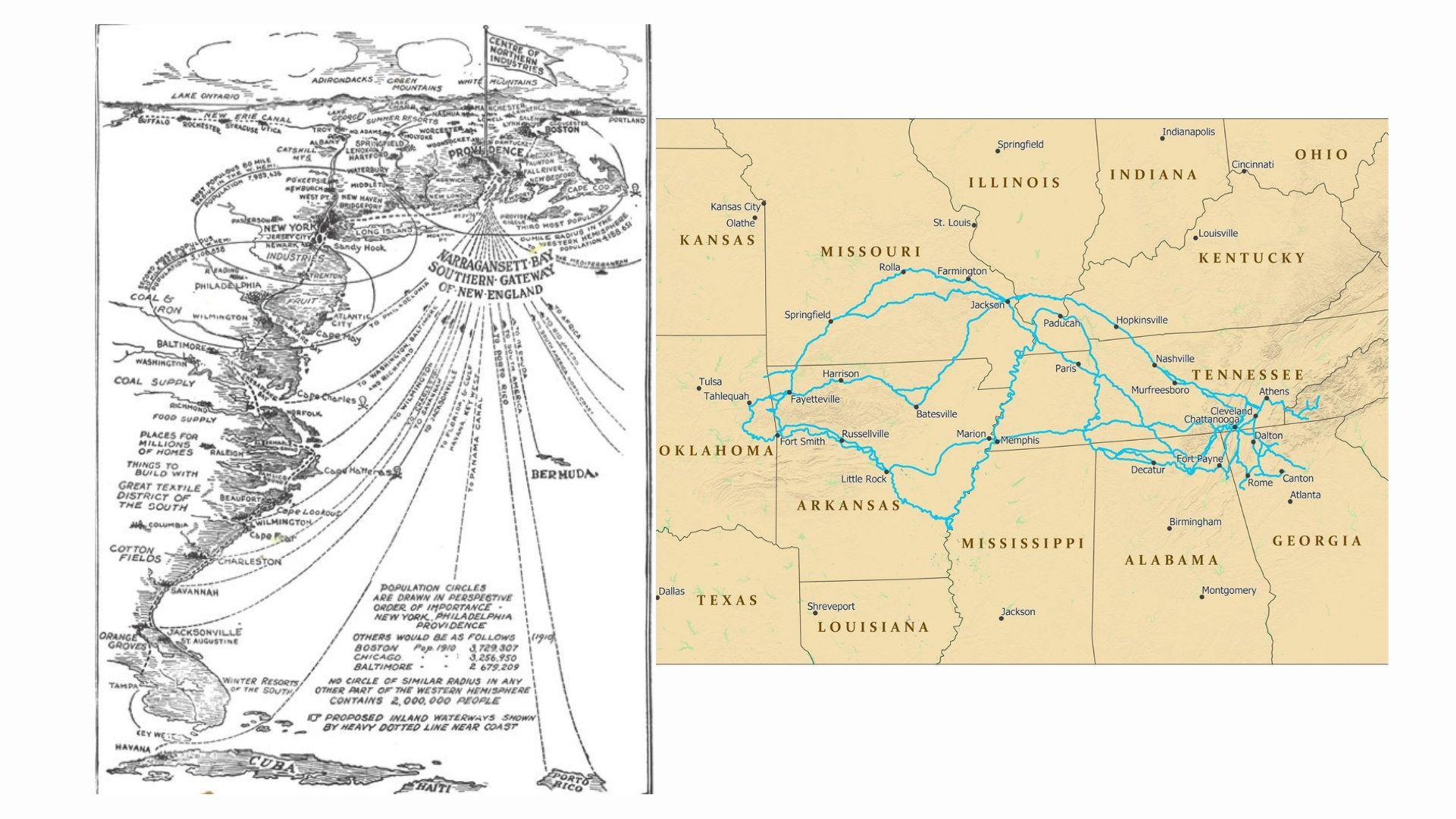

When we think of mapping we do not often think of charting the oceans, however, it needs to be considered that the same colonial mapping paradigms are indeed applied to all waters. Images 2A and 2B are two maps that depict colonial movements on the Land and the Sea. What you will notice in the image 2A is the categorization of capital assets such as “cotton fields” in what is now Georgia, the “great textile district of the South” in what is now the Carolinas, the “Coal and Iron district” of what is now Pennsylvania, and the boastful flag of Providence, RI declaring the “Center of Northern Industries''. This map is narrativizing the capitalist enterprise of colonialism: male+christian+white supremacy, through the renaming of the Land and Sea with no consideration for the pre-existing human and non-human cultural structures. The almost straight lines radiating from Providence, RI through the “Narragansett-Bay Southern-Gateway Of-New-England” highlights the consistent attempts by colonial forces to dominate the oceans just as they dominate the Land. This map demonstrates the attempts by colonial forces to landscape the oceans. One is inspired to question who drew this map and what was being asked of them in terms of cartographical execution. How did this person perceive the Land, Sea and the pre-existing inhabitants? Image 2B is a migration map depicting the violent removals of the Choctaw, Chicashaw, Cheroke, Seminole and the Creek from their traditional homelands and seasonal migratory traditions. In this map we see the Land has been landscaped into property sectors similarily to the Providence plantations and slave ships made visible by what we now call state lines (shown in black). The blue lines represent the forced migratory paths of the Indigenous nations who were violently relocated to new designated homes (often in the form of reservations) where they effectively became refugees in their own territories. Image 2B is another example of narrativizing the Land through mapping for the purposes of successful capitalist enterprise resulting in the erasure of the Indigenous people and the interrelationality between them, the Land and its other inhabitants. These two images demonstrate visually the manner in which colonial mapping flattens the Land and the Sea effectively eroding all animacy-beingness.

Image

New England Southern Gateway 1912. New England's Southern Gateway (Providence: Providence Board of Trade, 1912] Foundation, Rhode Island. Putting Rhode Island on the Map - Roger Williams Initiative, www.findingrogerwilliams.com/essays/putting-rhode-island-on-the-map + Trail of Tears Map. The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail depicting the forced migration of the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Cherokees, Seminoles and Creeks passes through the present-day states of Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. [Source: https://www.nps.gov/trte/planyourvisit/maps.htm The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail.]

Sympoietic Mapping

Sympoietic Mapping, is a mixed media painting which charts the relationship between Manycolors, her daughter and the other realms to which they access through the Waters. Present are specific Animal and Spirit Nations who help them along the journey, reminding them of how to embody kinship. The environment is a fluid substance emulating the Earth’s waters, a womb and the Spirit world. Dissimilar to a colonial map, this map does not attempt to flatten the waters nor divide them up into quadrants, rather this map places the people inside the water - a location rooted in interrelationality. Sympoietic Mapping is speaking to the way in which Indigenous creation stories are maps which do the work of storying and, contrary to colonial thought, are linearly multiplicitous as they weave together many realities Yes, linearly multiplicitous is somewhat oxymoronic, though thoroughly functional when it comes to how maps can chart and track multiple timelines. Ryan Spring, Choctaw Oklahoma Citizen and Historian, converses with Manycolors in this thesis work that the multiple creation stories of the Choctaw people is evidence that linear time is not singular. In fact, the presence of many creation stories is evident that many timelines exist intersecting at differing moments. From this perspective, maps are multidimensional.

Japanese settler aloha ‘aina Scholar and Activist Candice Fujikane situates in her book, Mapping for Planetary Abundance, mapping as an act of charting interrelationality which she does so through focusing her research on the ways that the Kānaka Maoli (Indigenous Hawai’ians) do this type of holistic cartography. The Kānaka Maoli’s mapping practices are embedded in their storying of their experiences of the Land which strengthens their bonds to it and other inhabitants. Fujikane highlights the ways in which the Kānaka Maoli cartographically record the Island’s changes through their oral migration story of the mo’o, “the great reptilian water deities” who travel down from their “home islands in the clouds to Hawai’i” (Fujikane 2021: 1). Fujikane draws attention to how the Kānaka Maoli map topographically through a genealogical connection to the Land, highlighting ecological impacts due to the bonds (as opposed to ownerships) between all the beings that make Hawai’i exist, such as the Land, Waters, Air, Lava, Animals, and Spirits. This is a pivotal distinction between colonial mapping and Indigenous mapping in that charting bonds makes male supremacy/colonialism virtually impossible.

Ultimately, Sympoietic Mapping is a visual representation of what is possible when we rotate towards an ontology of care, when our mapping practices are rooted in genealogical bonds to the Land. This map is asking that we (homo sapiens) consult the non-more-than-human inhabitants of this Planet for examples and directions on how to rotate into an ontology of care which is the only way to ensure not only our futurity, but to regain our place within Planetary interrelationality.

Image

"Sympoietic Mapping" Lilly Manycolors 2022 mixed media on canvas 113" x 72"

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles