Vrinda Mathur

A Fleeting Landscape:

Resurrecting the edges of the estuary

A Fleeting Landscape invites the city dweller to experience a mixed media microcosm of the marshes and discover what has been obscured through the encroachment of urban development.

From the salt marshes of Rhode Island to their tropical counterpart in the Sundarban (pronounced: shundar-bon) mangroves of India, wetlands are the world’s natural barriers. Fighting against extreme weather events between land and sea, the edges of this fragile ecosystem continue to shrink and degrade as anthropogenic stressors (infrastructure development, unsustainable land use, and aquaculture) increase. In a 2022 report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) persuasively argues for the protection of wetlands as they are key ecosystems that help regulate temperature rise to 1.5º C. Despite the urgency, an appreciation for the wetlands exists at the periphery of attention.

Your eyes and minds become tools for recognition, your voice — an activation. You are, a marshian

Have you noticed the street tree? Partitioned next to a bench, next to a trash can, next to a streetlamp. Some blossom like a newborn's cheeks, some a blinding bright green, and, when the seasons change, they bring out their best fall monotones. You may have seen trees elsewhere too. In the park, while on an evening stroll, or on hikes in a forest, on television when there is news of fires spreading across the Californian coast, and on social media when climate activists passionately share their worries about the dying Amazon.

You are given the opportunity to build a connection with nature through trees, you may have jumped and sat and climbed and hugged them. You might feel for them. You might know you need them. You might even want to protect them. You can be a steward, hugger, and nature lover.

But have you ever seen a marsh?

Striated along our coastline, next to the white sand, next to the pebbled pathway, next to the ocean. Coastal wetlands guard our shores as the first line of defense against extreme weather events. They hide and seek with the tide, doubling up as a nursing ground for a myriad species of animals and birds. They are lush and green with pops of pink in the summer months, fading to a golden sparkle over the winter.

You don’t see the marsh by the street, instead, you fill the marsh to make your streets. You don’t see them by the beach in the excitement of rushing towards that dip in the ocean. You don’t see them on television because you have the luxury to skip, ignore, or move on, and you don’t see them on social media, because, the Amazon is dying.

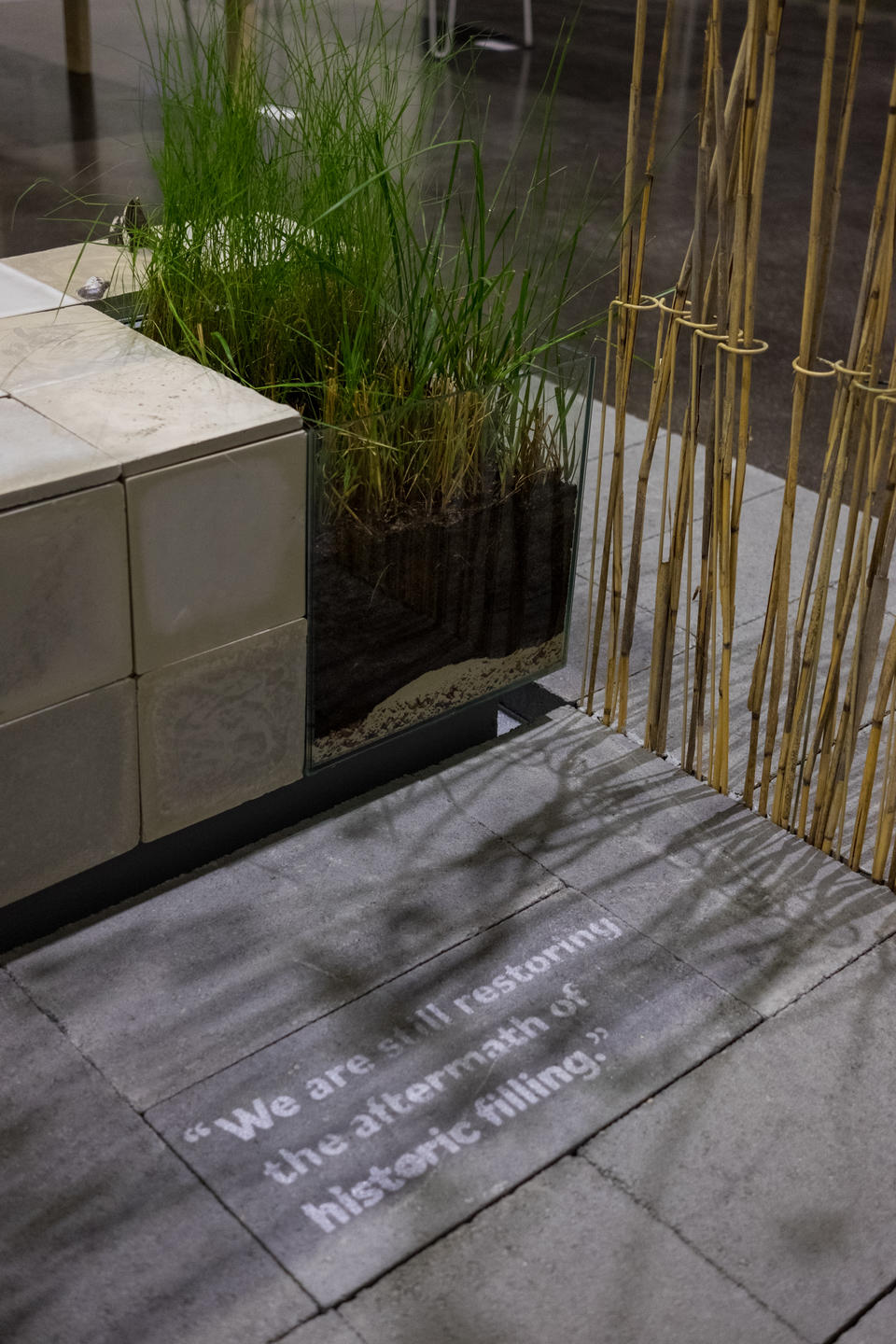

Image

Gateway to the marsh

Native marsh grasses, glass, sand, peat, hydraulic cement, plywood

48 x 18 x 16 inches

2022

By embedding ecological curiosity* through objects in the public space the proposed design becomes a physical embodiment of historical and scientific research. The concrete tiles are symbolic of extractive interactions, layered atop the stratigraphic representation of a salt marsh.

Ecological Curiosity refers to an inclination or individuals’ drive to learn about local ecology and put the learnings into action through a community-powered response.

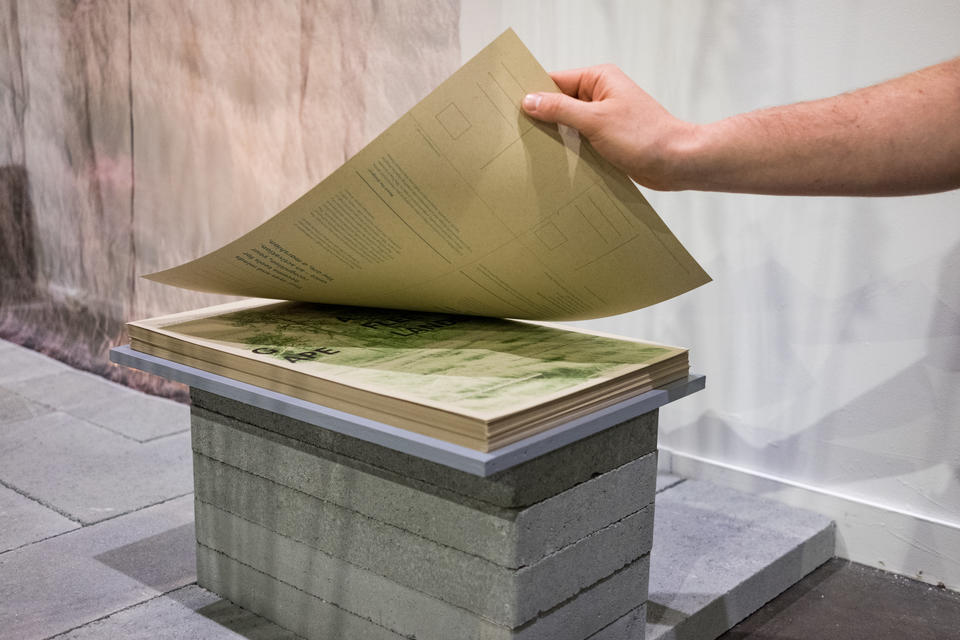

Image

Street view(s)

Image

A square foot of the marsh was created using gravel, sand, and peat. It is adorned with native marsh grasses namely Spartina alterniflora and Distichilis spicata which were sourced locally and planted to represent a microenvironment.

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles