Erika Kane

Adaptive Reduce: Forging Architectural Futures Through Degrowth

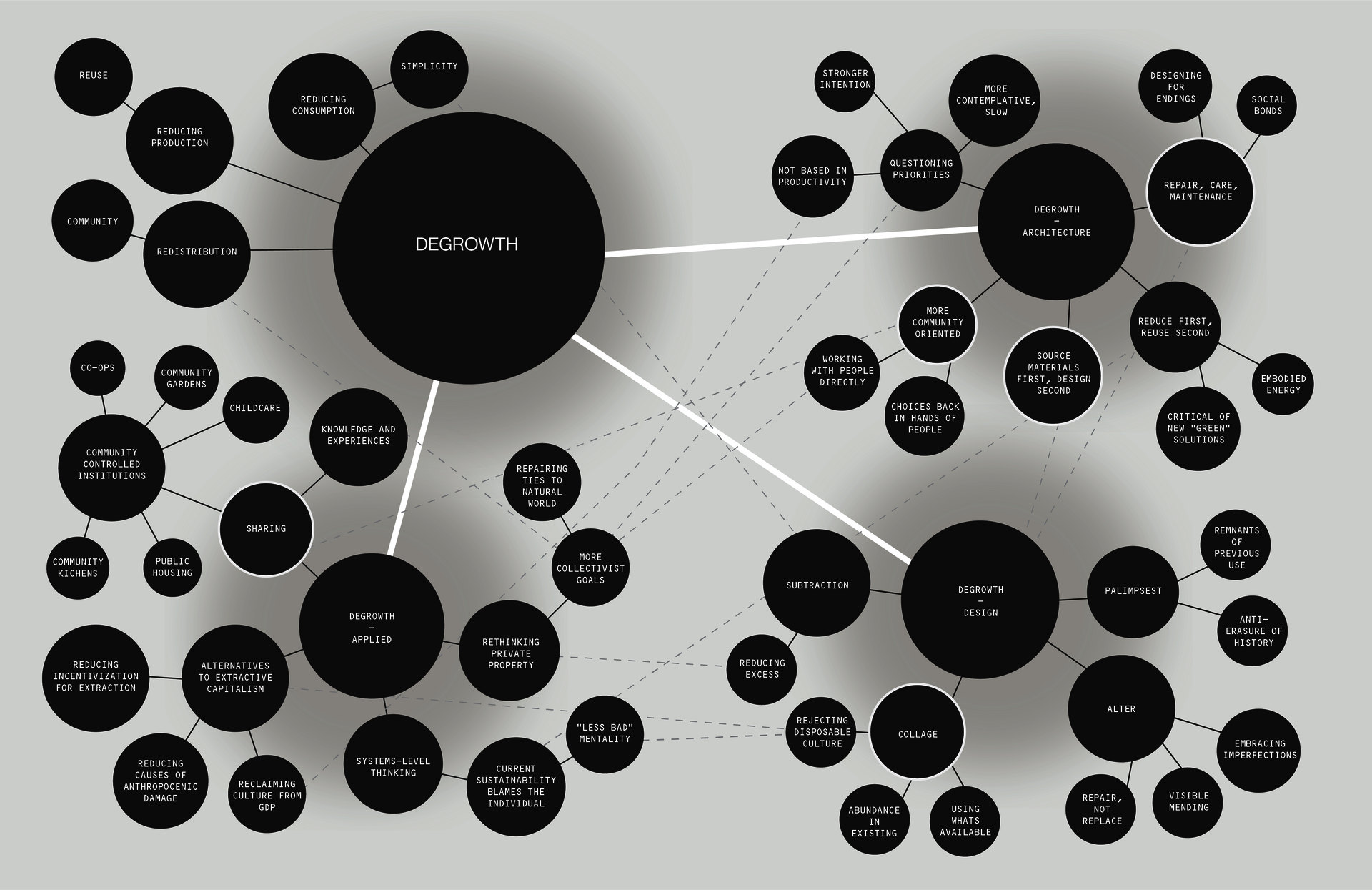

Architectural education and practice exist under the premise of expansion – there will always be more to build and more to design. On a planet of finite resources, a resource crisis is inevitable if we continue to live in pursuit of infinite economic growth. There is widespread awareness of the damage caused by anthropocentric habits in the West, and there have been great strides in development of “green” materials and solutions. But what is the point of building more, though greener, if we are still building endlessly without utilizing the abundance within the built environment that typically gets dismissed as “waste”? This thesis seeks to translate the concept of degrowth, the downscaling of production and consumption, into architectural language, for more regenerative, equitable and collectivist futures.

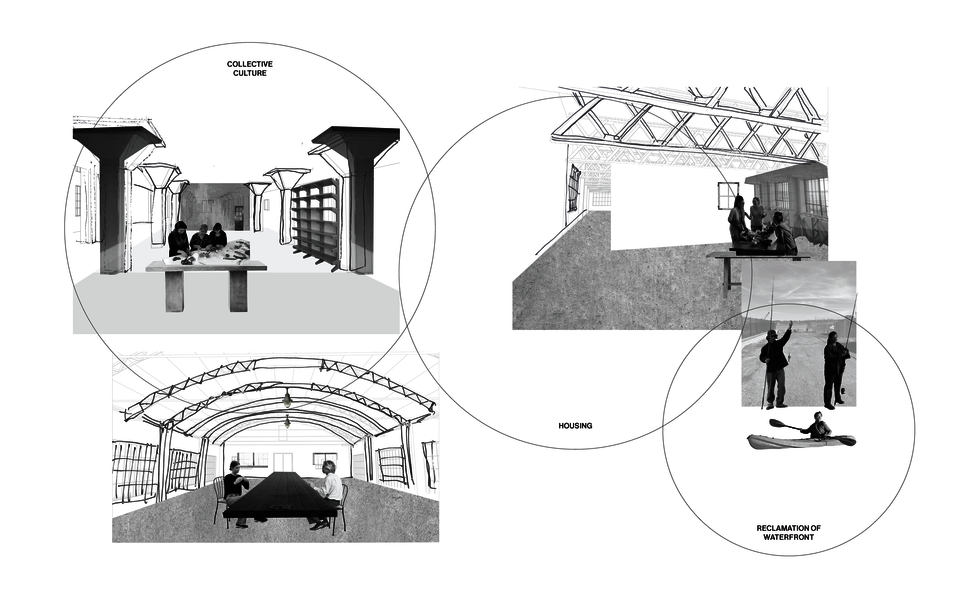

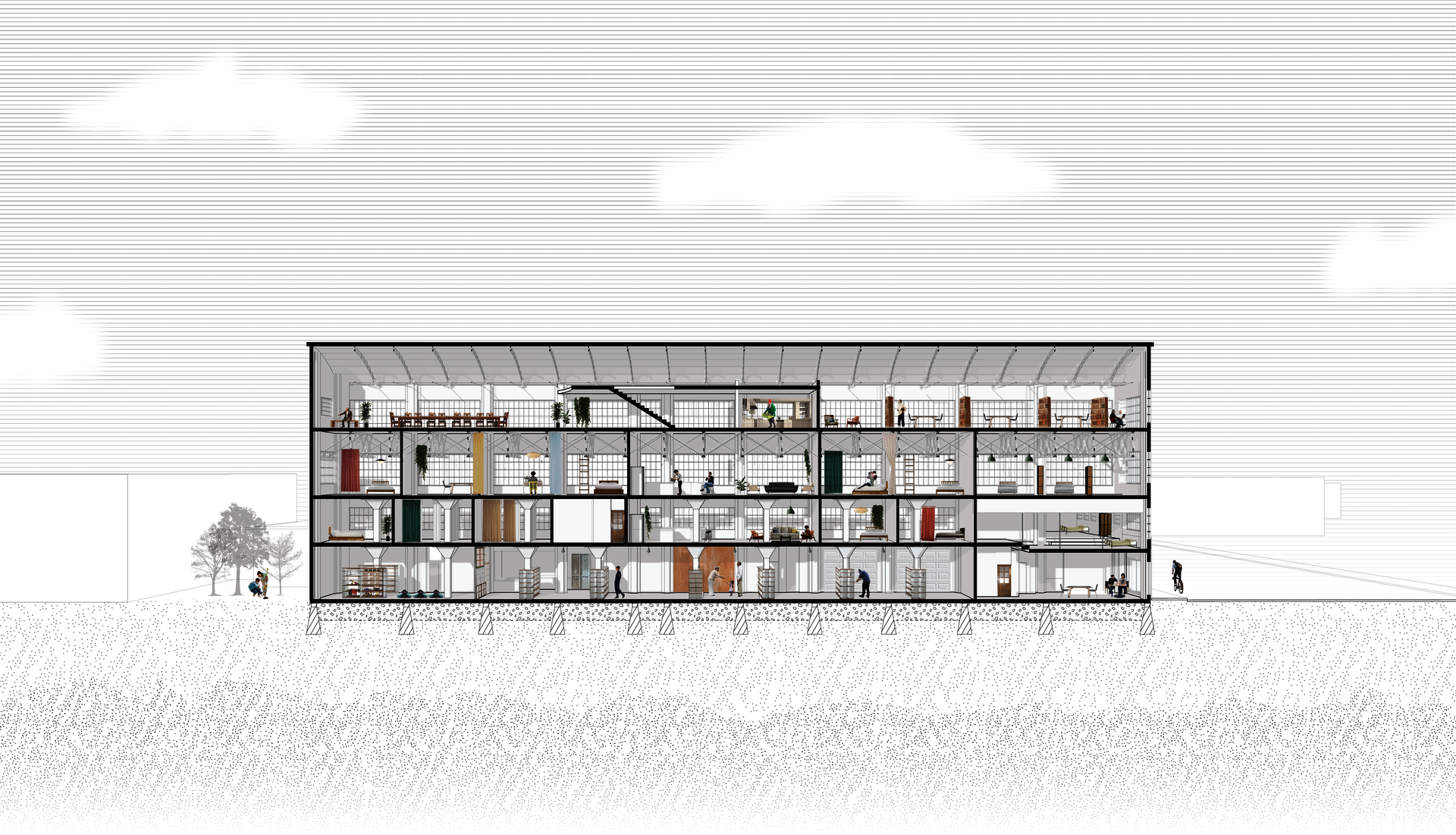

The following proposal explores how an architecture of degrowth can facilitate sharing within a community and reclamation of the neighboring waterfront through the adaptive reuse of obsolete industrial infrastructure. Situated amidst oil tanks and scrap yards, the former Providence Gas Company Purifier House, built in 1900, is adapted for reuse in a way that opposes its original role within the fossil fuel industry of Providence Harbor. It addresses the qualities of the South Providence neighborhood and seeks to elevate its strengths for its current residents. If the aim of design practice is less focused on economic productivity, architectural design can become a more community-oriented, thoughtful, and contemplative process. Collectively we need to consider how degrowth can pose challenging, enriching opportunities for construction and help architects question priorities while also challenging existing pitfalls of a field that assumes perpetual growth.

Image

Adaptive Reduce: 1. A term for architecture that acknowledges where architecture is not necessary, making space for resource conservation through the reduction of consumption and production where possible. 2. An alternative to the term ‘adaptive reuse,’ which, as a field, is praised for its environmentally sustainable aspects but requires more thoughtful application for existing residents and surrounding context. 3. A term that acknowledges where degrowth can be beneficial and where it can benefit from being more inclusive.

Relics of Industry

This thesis exists somewhere between speculation and reality. It is at once engaging with industrial growth and development of the past, and the present dangers of its aftermath in the contemporary world.

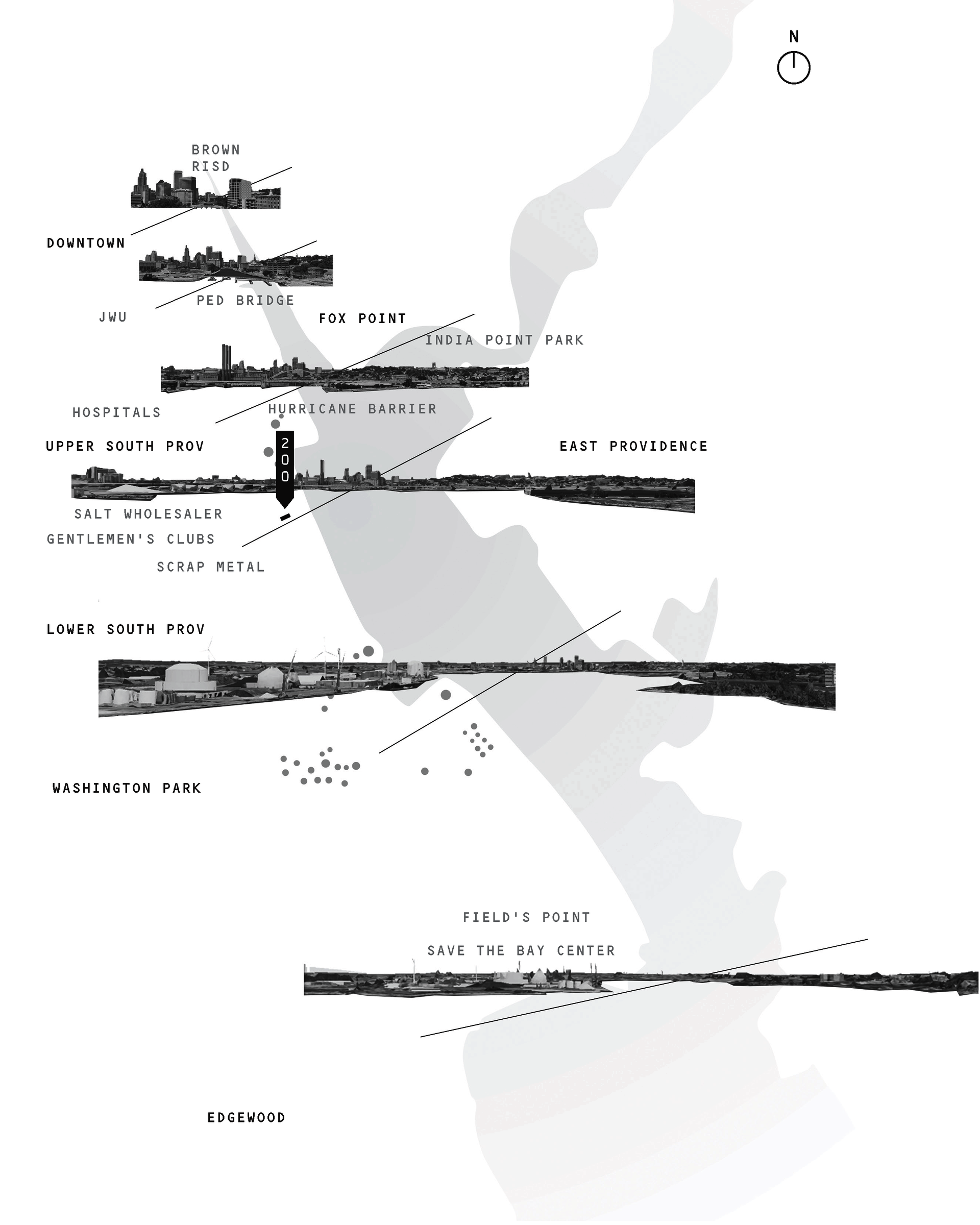

The industry of Providence Harbor historically shaped the city of Providence into one of the busiest ports in New England for trading and shipping. During the Revolutionary War, the British occupation of Newport brought most of the shipping industry North to Providence. In researching the harbor, one will find a variety of the transitions that have occurred. Initially the salt marsh around the harbor was filled to increase the usable land footprint, then it was developed to house water-based industries and eventually to store and facilitate energy production. Eventually the energy standard transitioned from coal to oil, and in the 1960s the highway was built, separating communities and increasing car travel through the area. Today, industrial Providence is a graveyard of past innovation with a nascent appearance of green energy. When thinking through the history of Providence Harbor, one thing becomes clear – the harbor has gone through transitions before and it will go through transitions again.

In the field of adaptive reuse, we find ourselves grappling with relics – the toxicity of harmful industries, the ghosts of those displaced, and the physical remains of construction waste and unwanted material. Often adaptive reuse is championed in the field for its sustainable aspects of working within existing buildings and structures. But as I understand it now, “sustainability” concerns much more than the existing environment, it also concerns more systemic conditions, such as community, context, and history. Specifically, we rarely discuss gentrification in the educational space and its broadly detrimental effects on communities. While growth in the past may have looked like the introduction of innovative forms of energy production, it’s harder now to see growth as a “rising tide lifts that all boats,” as famously said by John F. Kennedy. Today it has become clear that growth directly benefits the few by exploiting the majority. Architectural and urban “development” are good examples of this, in a sense of who is benefiting from the gentrification of existing communities as we propose these architectural projects, and who is displaced. Ultimately, the ethics of private property must be turned on its head, shaken, and reconfigured until more equitable conclusions can be derived.

In other words, growth was once a celebrated notion, representing progress, technological advancement, and the accumulation of wealth. We harnessed Nature, extracted from it and learned how to commodify it for our benefit. The industrialization and growth of Providence was the reason it could become this city it is today. But what this growth was missing then was foresight. Within all the excitement of growth lacked the questions of What comes next? What problems are we creating, and who will clean up the mess?

Degrowth can have the power to improve our lives if we do not succumb to it through a societal collapse. Now, when we ask ourselves What comes next?, we must ask What will we be proud of? and What do we have to redistribute?

Image

Georgios Kallis defined sustainable degrowth as an “equitable downscaling of production and consumption that increases human wellbeing and enhances ecological conditions.” Our current rates of consumption are testing the biophysical limits of Earth. Reducing these ecological demands is the only way to decrease the rate in which we meet those limits, and in doing so we must also create the conditions for resilient ecosystems and enhancement of life.

Providence Gas Company Purifier House (1900)

A long-standing witness of an ever evolving industrial waterfront.

The choice of the former Providence Gas Company Purifier House (1900) for my site was a deliberate one in giving a convivial new life to one that played a critical role in the fossil fuel industry. I think there is great symbolic and functional value in transforming old energy infrastructure into social infrastructure.

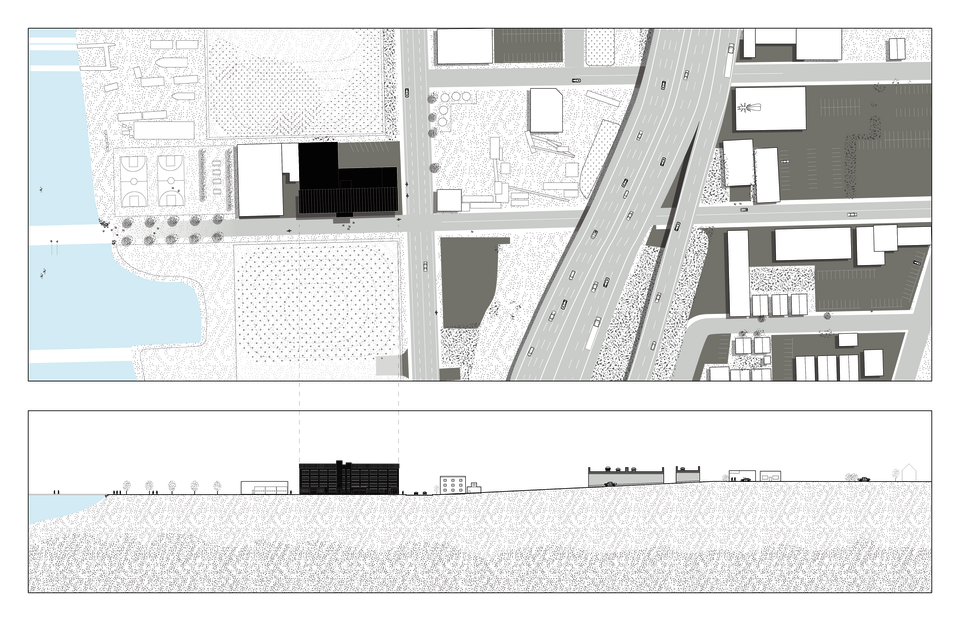

200 Allens Ave is a large, four-story, steel frame, reinforced concrete and brick industrial building located at the corner of Allens Avenue and Public Street on the Providence Harbor. It is a long, narrow building (41’ x 178’), oriented east-west, with an elliptical arched roof and a four-story stair tower in the center of its north elevation.

The building was used by the Providence Gas Company to purify the gas manufactured at the South Station until the plant was closed in 1917. In the 1920s, a new owner modified the interior spaces and exterior skin of the Purifier House so that it now resembles a more conventional industrial building. Through the 1960s, successive owners made several additions, mostly along the south elevation.

Image

The site is proximate to the I-95, which contributed to the transition of Allens Avenue from an active harbor-based industrial trading port to one that also supported automobile travel, parking, and industry. It’s zoned as a W-3: Port/Maritime Industrial Waterfront District, and there are multiple oil tank farms belonging to different companies: Sprague, Shell, National Grid, and Provport. The current primary import is petroleum, but it also supports the imports of asphalt, cement, and road salt. The industry has contributed to many pollution and health concerns, including higher rates of asthma, in residents of the neighboring residential areas.

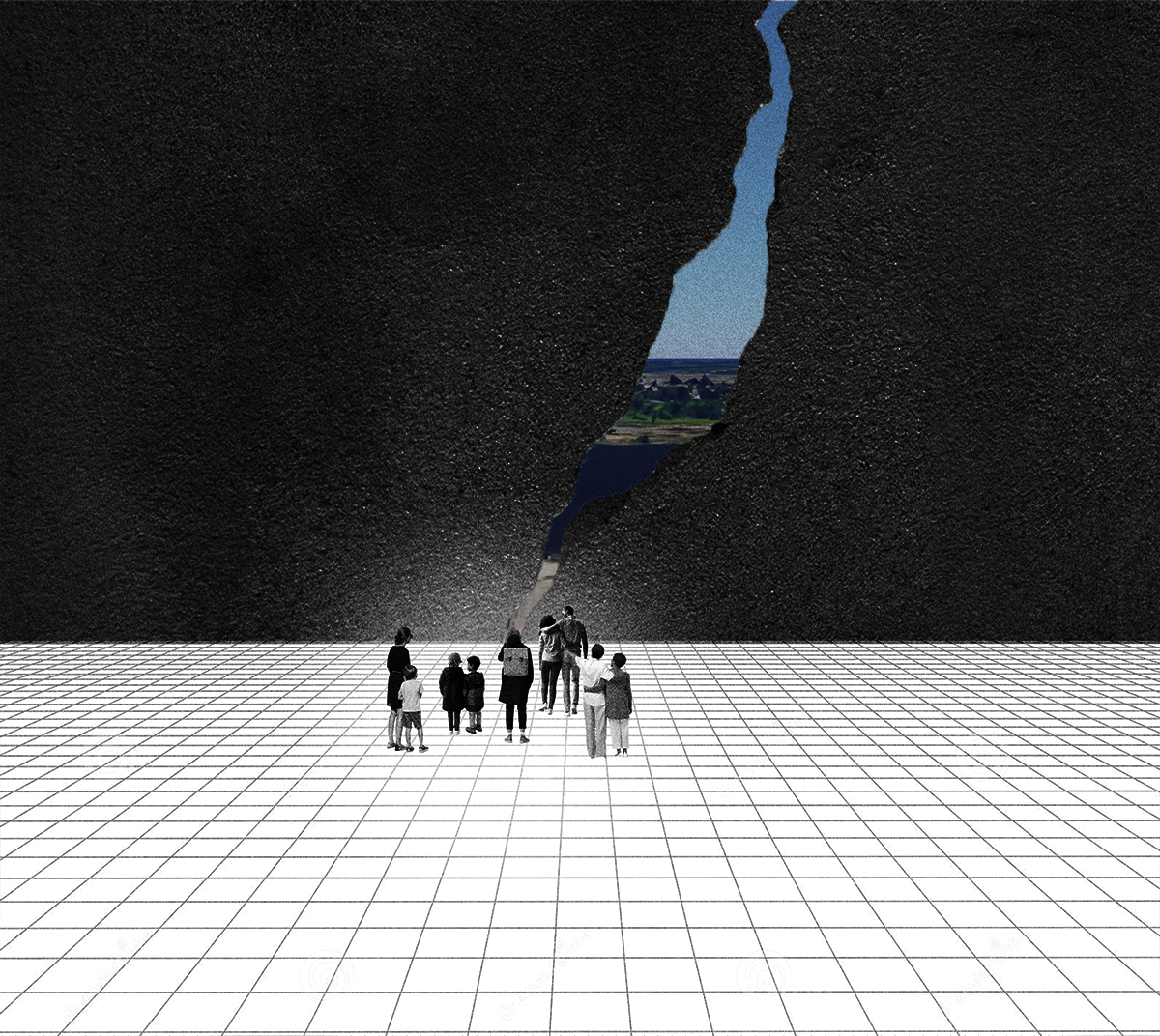

Public Street, Public Access

The best intervention would be a total reclamation of Providence River, where oil is replaced by cleaner forms of energy production. But considering the fact the community is still protesting Shell’s expansion on the harbor, the ability to gain public access to the waterfront via Public Street was a big win and should be celebrated. This public access point (one of three along the harbor) to me symbolizes a crack in the wall. Similarly to how a crack exposes where the whole wall can be torn down, it is an opportunity to see how things can be different – a catalyst for change.

Designing for degrowth may be misinterpreted as anti-design. In my interpretation, rather, it works as a tool for thought. It asks the questions: What is necessary? What is excess? What have we accepted as the norm without question? It helps us reevaluate what we waste resources on, how to be more intentional with our surroundings, and how to find alternatives to extractive practices that are fundamentally unnecessary and harmful.

We live in an age of widespread understanding of the environmental destruction of the waste we produce, just as new ways of creating and building are at the forefront of the design world. New bio-materials, new technologies, new “green” solutions – all of which rely on consumption, perpetuating and mimicking the same destructive systems already in place, with only a slightly lighter impact.

The “greenwashing” that occurs include technologies that are still inaccessible to many and are resource-heavy to produce. The inefficiencies caused by the hastiness of growth-inspired architecture would be much better off with more thoughtful planning for orientation, material choice, and actionable plans for maintenance. Additionally, contemporary sustainability standards for buildings and objects, such as LEED, measure success by meeting a certain level of “sustainability.” By doing so, it distracts us from considering whether or not the building or object needs to be created in the first place. Regardless – the buildings have been built. And what do we do with them now?

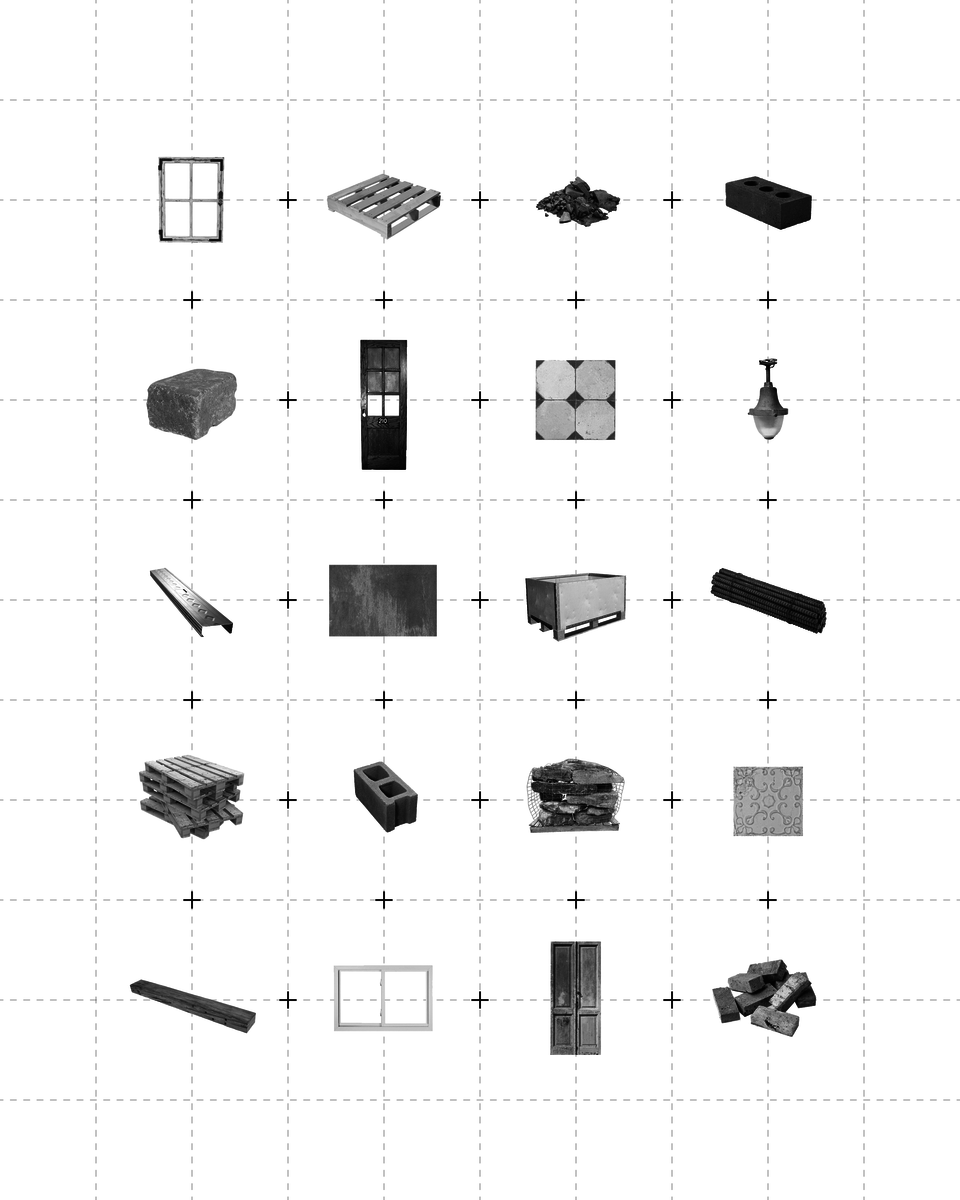

We must begin to search for alternatives to newly mined resources before we transition out of necessity. “Urban mining” is a term used to describe the use of deconstructed/demolished building material to mitigate the need to produce new construction materials from natural resources. This has the potential to save the large amount of embodied energy expelled in the extraction process. When resource mines dry up we can look to the material typically discarded as waste. Where buildings and structures cannot be saved for new use, they can be seen as materials depots. Abundance can be found everywhere, if we put more time and care into the end of life of urban buildings.

Image

A crack exposes where the whole wall can be torn down.

Intervention

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles