Kate Ross

Out of the Box: Rethinking Wildlife Exhibition

We are living at a time marked by unprecedented rates of extinction precipitated by human impacts on the environment. Over the next twenty years, more than 500 species of land animals alone are likely to be lost forever. In order to more responsibly inhabit this planet we share, widespread behavioral and societal changes are necessary. The field of exhibition and narrative environments is uniquely equipped to inspire positive change through the design of meaningful and accessible experiences with and about nature and non-human animals. However, traditional modes of wildlife exhibition, in which individuals are removed from their native habitats and put on display in artificial environments, are unproductive—if not paradoxical—to the mission of conservation.

In reconsidering how, where, and what wildlife is exhibited, this thesis proposes that framing the city as a site of wildlife encounter has the potential to combat many of the problems inherent in traditional wildlife exhibition. Using Providence as a case study, the project demonstrates how we might convey more authentic narratives which take into account the interconnectedness of humans, animals, and the environment we share. The city site also affords opportunities to reach visitors who may not otherwise engage with wildlife or consider themselves to be environmentalists. By highlighting overlooked urban critters, the project questions which animals deserve our attention—positing that memorable experience with any animal might be enough to initiate caring for all animals.

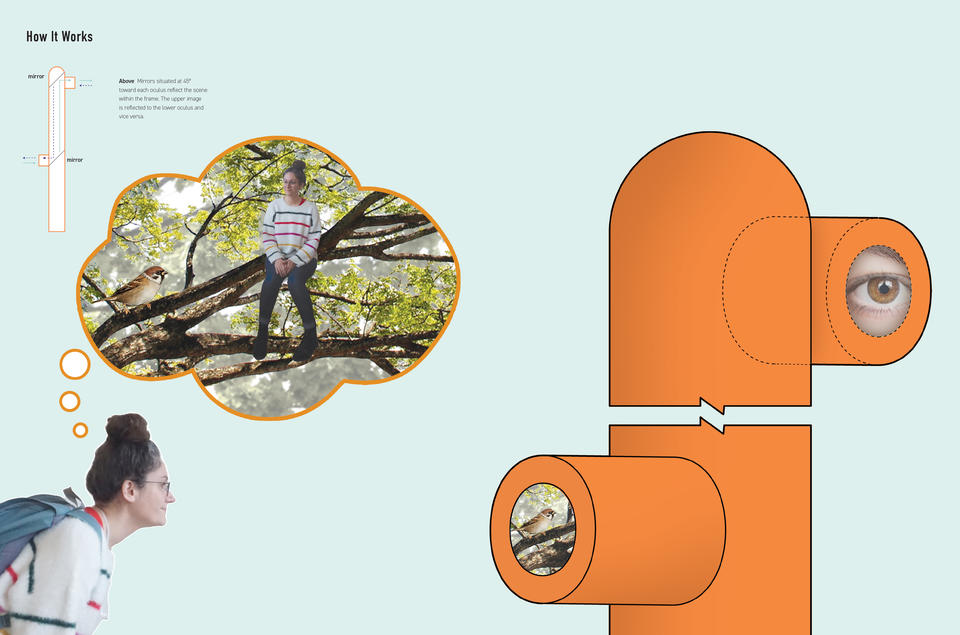

The intervention will include a system of viewing devices dispersed across the city. These objects will catch the attention of passersby, disrupting their normal routines and inserting a curious, exciting opportunity. As they peer into the device, users will assume new perspectives—viewing animals up-close and seeing the world through their eyes.

Image

Wildlife is present, but often overlooked, in the city. With more and more people living in urban centers, the city presents an opportunity to increase enthusiasm for animals and concern for their wellbeing. In light of accelerated extinction rates, it is critical promote concern and caring for our non-human neighbors.

On Looking

The act of looking is central to the zoo experience. While the missions of zoos have changed in the centuries since these institutions began to emerge, spectacle and objectification remain at the root of how they function as a public-facing entity.

Looking is of course integral to the discipline of exhibition design more broadly as well. Museums hold and care for artifacts of historical and cultural significance—objects belonging to the public and presented to us in creative ways so that we might continuously learn new things about ourselves and the world around us.

The museum gives us the opportunity to be in the presence of such objects, which are steeped in history and have, in some way or another, shaped our lives today. The in-the-fleshness of these experiences can be profound, and this ability of exhibition design is what zoos depend on. But what happens when the object of our gaze can look back at us?

Just as being in the presence of important objects can move us, in-person experiences with live animals can no doubt affect us in powerful ways. However, the zoo model is predicated on our caring being species-specific. In order to care about Asian elephants, for example, must we see one firsthand? Even if it means that elephant cannot roam free? What does this seeing really do for us or the subject?

I propose that a meaningful, authentic, even serendipitous encounter with any animal has the potential to be more positively affecting than a fabricated experience with an animal held captive—no matter how big, beautiful, strange, or rare.

Among other factors, this hypothesis is very much concerned with our ability to genuinely see a given animal subject. I question whether this is truly possible in the zoo, where animals have been stripped of so much of what makes them them. Rather, seeing an animal on its own terms, in the wild, affords us the chance to better understand who the animal is, its role in the environment, and even how we might influence one another’s lives. Moreover, non-captive wildlife viewing requires a bit of work on our part—patience, curiosity, attention—making for a more fulfilling experience.

Image

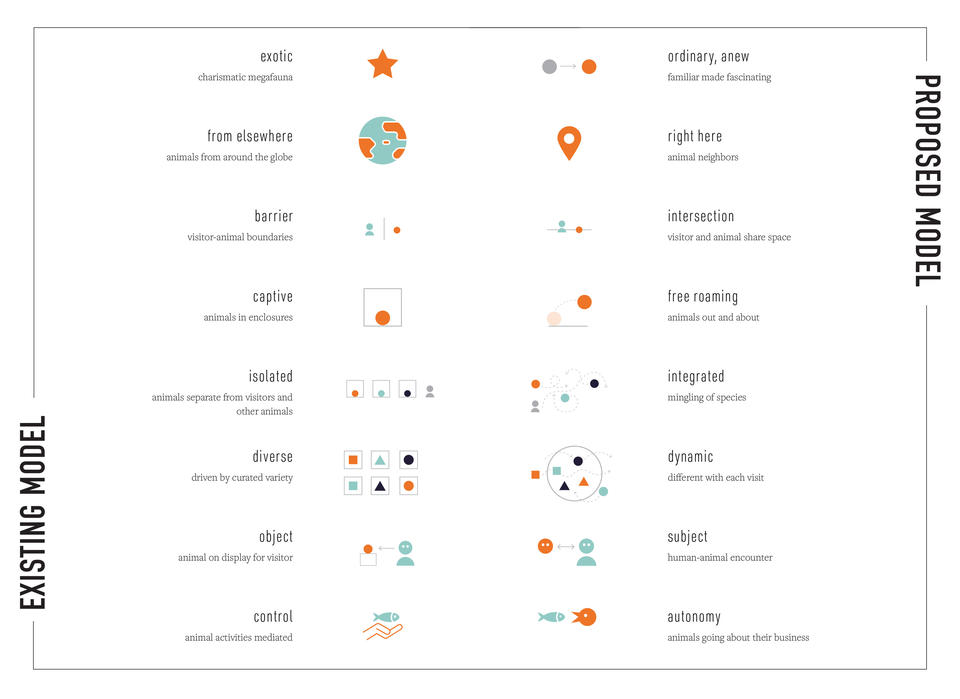

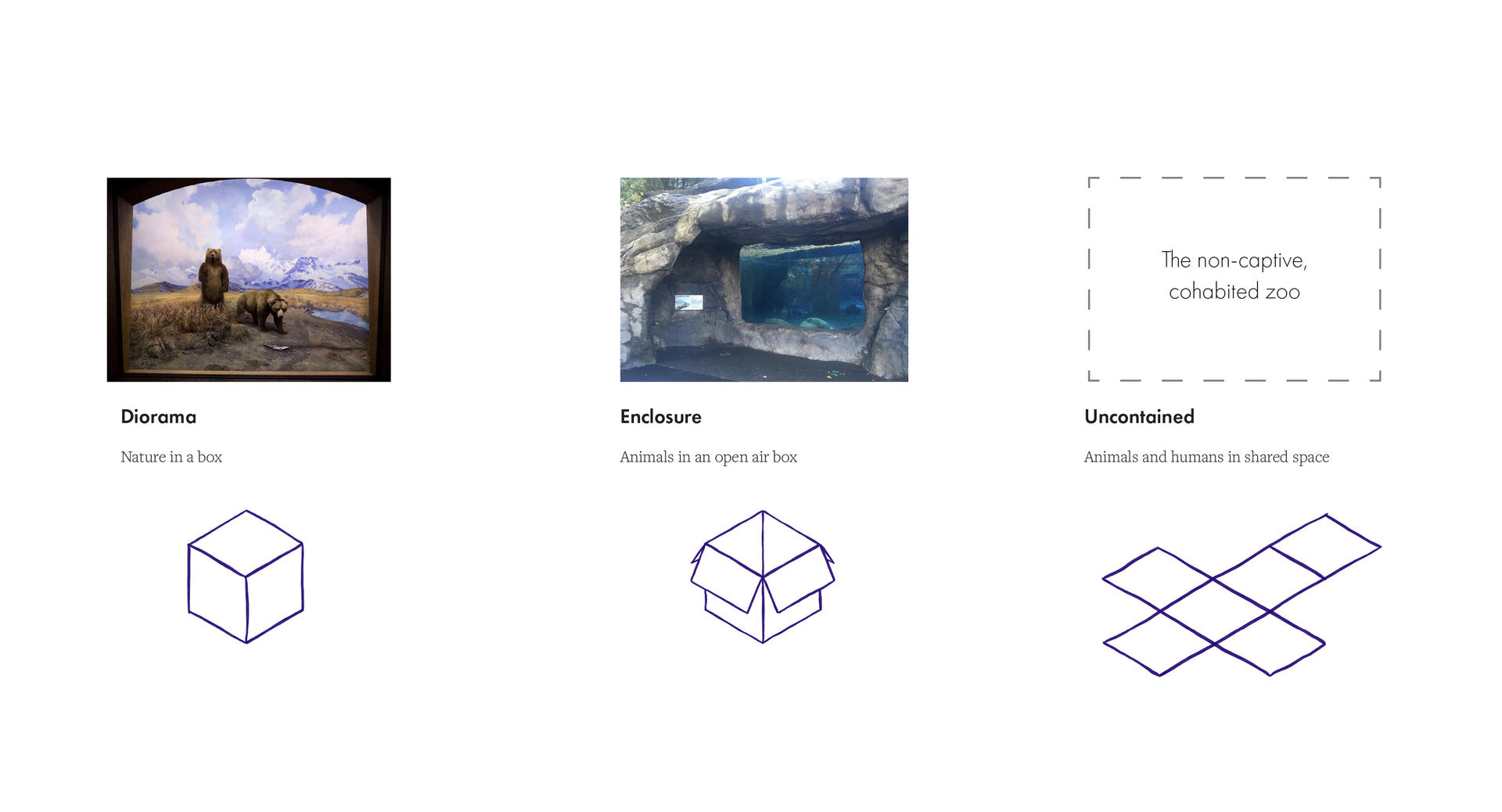

Existing wildlife exhibition frameworks place animals and nature in a box. However, nature is dynamic and ever-present. The current model removes wildlife from their native habitats, displaying animals in artificial habitats. The proposal leverages human-animal intersects to convey a wildlife narrative that includes the human experience and influence.

THE ZOO

The collecting of animals as a demonstration of status dates as far back as ancient Egypt, and this tradition gave rise to the concept of the zoo. The earliest zoological gardens were private menageries of the European aristocracy and were dependent upon elaborate expeditions for the capture and transport of exotic species. These animals were captured or traded and brought by sea to live on vast private gardens where they were sometimes made to perform or even fight for the entertainment of the elite.

Today we often hear about “good” zoos and “bad” zoos. These terms are meant to distinguish between roadside attractions—zoos which are palpably problematic in terms of animal welfare—and those zoos which are accredited by the American or World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Many of these modern zoos have placed conservation at the fore in their mission statements, but visitor awareness and even support of these goals is not always clear.

Indeed, the conservation mission of zoos seems paradoxical to the practice of keeping wild animals captive and displaying them for human entertainment. Zoos and their visitors appear to be confused about whether and how zoos are to be involved in wildlife conservation. With this conservation mission coming centuries after the birth of the zoo concept, it seems like a retroactive justification for the practice of captivity. The conflict between captivity and conservation must be reconciled.

Behind the scenes, many zoos are involved in research, breeding programs, and ex-situ efforts to aid wild populations of the species they exhibit. However, while zoos study and breed captive animals, wild populations continue to suffer the consequences of habitat loss, poaching, and climate change. The scale and urgency of these issues raises questions of where zoos should focus their efforts.

Today’s “animal ambassador” model is not unlike the justification of animal sacrifices for the natural history dioramas of centuries past. While these institutions have adopted more ethical methods of collection and exhibition, their missions and practices must be reevaluated in light of the realities of the 21st century.

Image

The proposal enables users to get a better look at urban critters. No need for captivity, the use of viewing devices offers a new perspective and up-close experience of animals we often consider to be pests or perhaps don't consider at all.

OUT OF THE BOX

This thesis proposes new approaches to wildlife exhibition and re-imagines what a zoo might look like. Where traditional methods of wildlife display and interpretation fortify imagined boundaries between humans and the natural world, I propose calling attention to the ways in which these worlds collide in our daily lives.

Rather than offering up renderings of far off places and exotic megafauna, I hope to highlight ignored or unnoticed animals living right alongside us in the city. Without curated and expertly decorated natural scenes or replicated habitats, a new zoo might ask it’s visitors to take a look at the environment around them and to consider the ways in which we have changed and sought to control it.

Indeed, these visitors might not be guests or tourists but local inhabitants of a space shared with the animals being “exhibited,” given an opportunity to meet and engage with their overlooked neighbors.

The proposed intervention is part wildlife exhibition, walking tour, and tactical urbanism. Periscope “portals” dispersed across the city will enable users to see local wildlife in new and surprising ways. Interpretive signage will give context by highlighting sights of ecological and historical significance. Abundant, scattered, and brightly colored, the objects will evoke curiosity and excitement from locals. The intervention will activate seemingly mundane corners of the city while enhancing popular landmark sites.

Both elements will be painted in “blaze orange.” This hue is used in many applications related to safety, construction, wayfinding, and hunting. The intervention—titled LOOK ALIVE!—is compatible with these other uses, as it prompts viewers to pay attention to their surroundings and change behaviors based on the safety and well-being of themselves and others. The color evokes a sense of urgency, significance, and even danger, while being bright, vibrant, and cheerful.

Image

The intervention is dispersed across the city—in parks, along waterways, on sidewalks, and near landmarks. Periscopes allow users to see into treetops and underwater so that they might observe creatures and behaviors that are otherwise invisible.

New Modes of Seeing

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles