Chhavi Jain

Curating within Indigenous Ecosystems of Art and Storytelling

Chhavi Jain is a writer, curator, and a performing artist trained in the Indian classical dance form, Kathak. She holds a Master’s degree in English Literature (University of Delhi, 2017) and has worked in the fields of journalism, public programming and production, publishing as well as arts management. At RISD, her research focused on creative ecosystems in Indigenous art, emphasizing on Indigenous self-representation and the need for care within the art industry. She co-founded RISD’s Performance Art Association (PAA) and directed a public performance. Chhavi is a recipient of the Graduate Commons Grant and the Turner Fund. Presently, she is a Post-Grad Tutor at RISD’s Center for Arts and Language and the Curatorial Research Associate at the Department of Costume and Textiles, RISD Museum. She seeks to create more interdisciplinary and immersive formats in storytelling in the interest of building a more equitable and accessible world through art.

Abstract

Curation brings art into an organized space. This has been structured upon Western colonial terminologies and logics that oftentimes do not translate, be it for the citizens of Narragansett nation Indigenous to Rhode Island, United States, or for the Adivasi community of the Gond Pardhans in Madhya Pradesh, India. This book thinks through creative ecosystems in Indigenous art as it navigates the markets, to create curatorial vocabularies and work with people who are in the business of making art, while laying emphasis on Indigenous self-representation and the need for care within the art industry. The text begins with a Prologue that recounts a personal historical account of the author’s family elders: Displacement from Sialkot during the Partition of India and their subsequent migration to Delhi. It sets the tone for the following chapters to exemplify legacies, habits and stories as embodied. They persist despite any borders [of the nation-state].

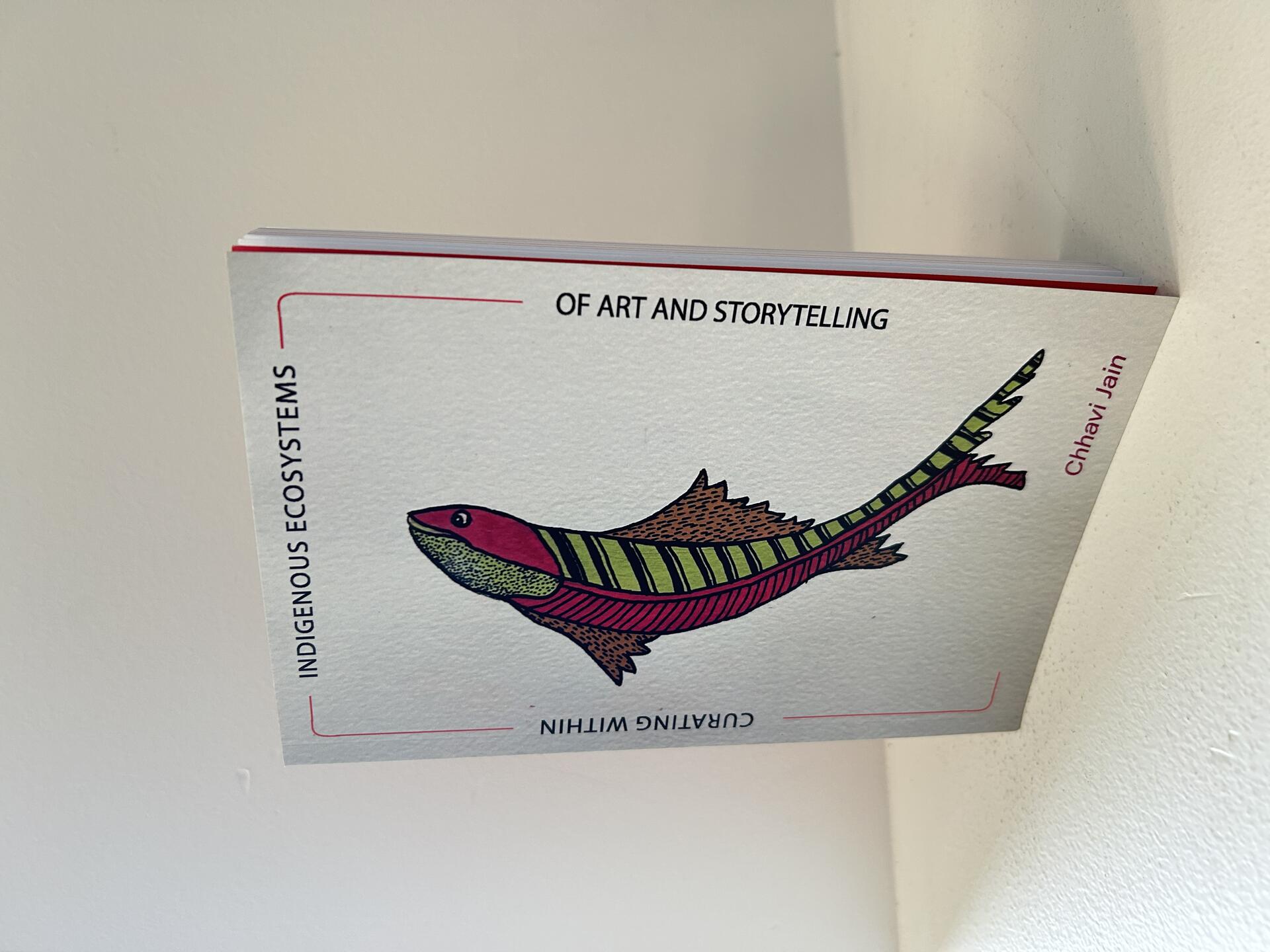

Image

The Book ft. 'The Fish' by Mayank Shyam & Chhavi Jain

The Story

"My sister and I, learned about the Partition in our history textbooks. When we learned that our grandparents had lived through it, we picked their brains with all kinds of questions and curiosities. They're upfront about not remembering very much, afterall it has been more than 75 years! And their ‘home’ is now in Delhi, with us. We are Sialkotis. People from Sialkot. Known to have an uncompromising sweet tooth. My grandfather and father really relish Indian sweets. My sister and I prefer chocolates, waffles, cakes.. This legacy of sweet tooth comes from a history that precedes me, and from people who are outside of me. And yet, they inform who I am and where I come from. An untouched pile of Indian sweets often disappoints our grandfather. But I believe that we are Sialkotis too, only in a globalized world. Sweet tooth translates differently through us."

Image

A snapshot of the northern India-Pakistan border (as circulated in India)

On Curation

The core themes in the book triangulate between Indigeneity, Art and Curation. This extends 3 primary lines of inquiry which are about curation’s relationship with care, storytelling and community. The questions and curiosities expressed in the work emerge from my curatorial practice in India. Curation allows me to bring my training, experience and interests together in generative ways. It enables me to expand my knowledge on various subjects and devise my own definitions of best practices. I meditate on curation as the space in-between, the gap, the bridge, the interstice– between the artist and the viewer. When it comes to Indigenous art, I ask: Why are the markets not, in the least, equitable for contemporary and contemporary Indigenous practices in a postcolonial global world?

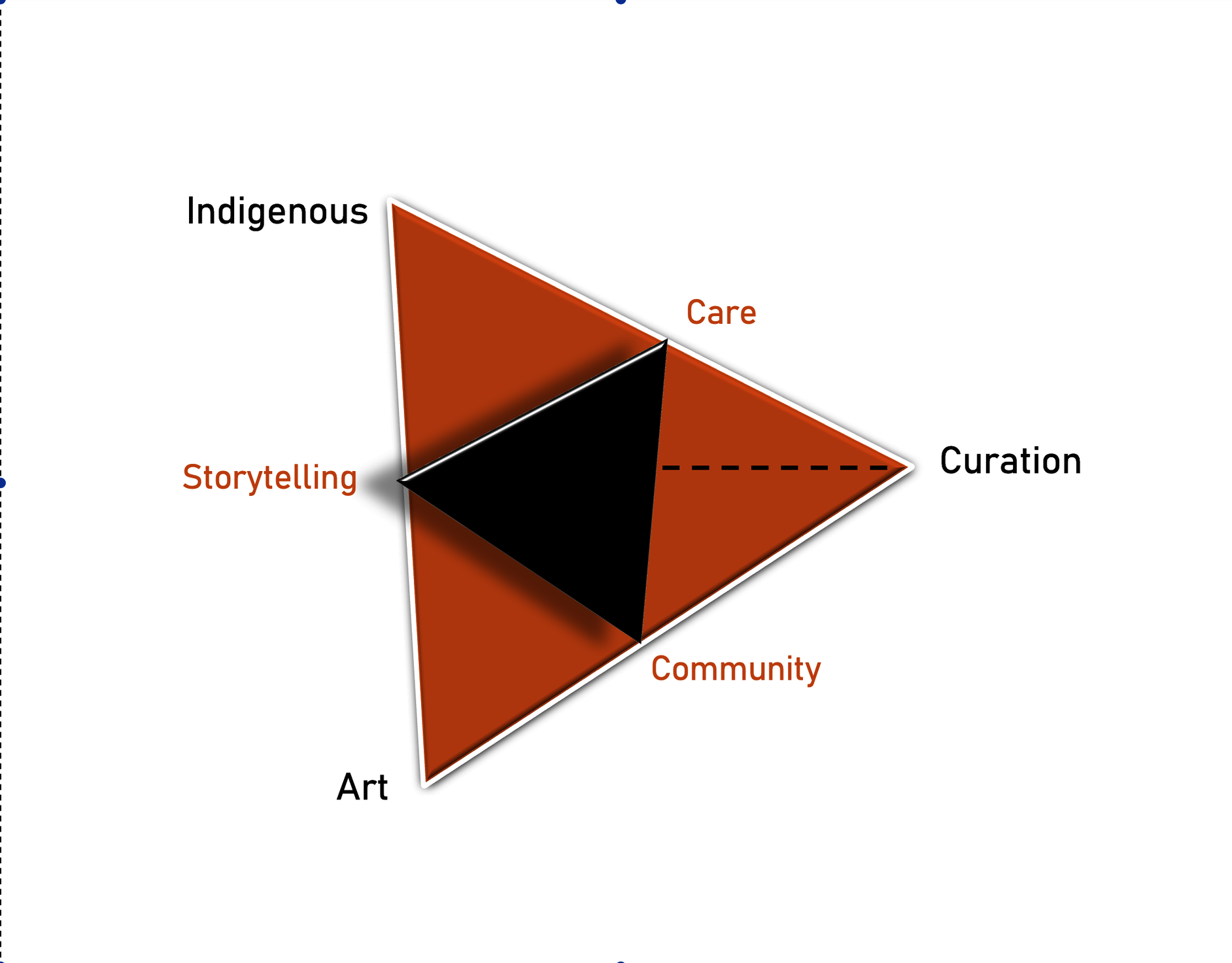

Image

Research triangle: Indigeneity, Art and Curation & their relationship with Care, Storytelling and Community

Tensions in Terminology

The term Indigenous (Latin: indigena or sprung from the land) has been used in colonial vocabularies indigenous to refer to flora and fauna, suffusing the term with a racial flavour. In India, Indigeneity is not rooted in the binary logic of the Indigenous and the settler colonial West. Adivasis (Sanskrit: earliest inhabitant) or tribals are commonly referred to as Indigenous people. Adivasi curation is a rare phenomenon as evidenced by the presence of only one adivasi curator in India, Madan Meena, from the Meena community, who is also a miniature artist. Drawing on this, I bring 2 specific case studies: virtual interviews with Angel Beth Smith, curator and artist as well as with Silvermoon LaRose, artist, educator, public servant and assistant director at the Tomaquag Museum (from the Narragansett community of Rhode Island); & Gond Pardhan community from Madhya Pradesh in central India.

A Snapshot

Chapter 1 begins with the tragic story of the famous Gond Pardhan artist, Jangarh Singh Shyam. It seeks to underline on the urgent need of care within the ecosystems of art. In the various aspects of an artist’s life, from representation to opportunity and access, I ask– ‘Where’s the Care?’ This chapter focuses on the value of care in curating Indigenous practices. You will see the development of some definitional frameworks that are carried through the book. I also emphasize on the value of working ‘with’ Indigenous artists as a means to support practices in a curatorial scape. This section ends with a focus on two museums: Arna Jharna in Rajasthan, India and the Tomaquag Museum of the Narragansett community in Rhode Island, U.S. that are built within the communities they represent, as opposed to the museumization for a presumed outside audience.

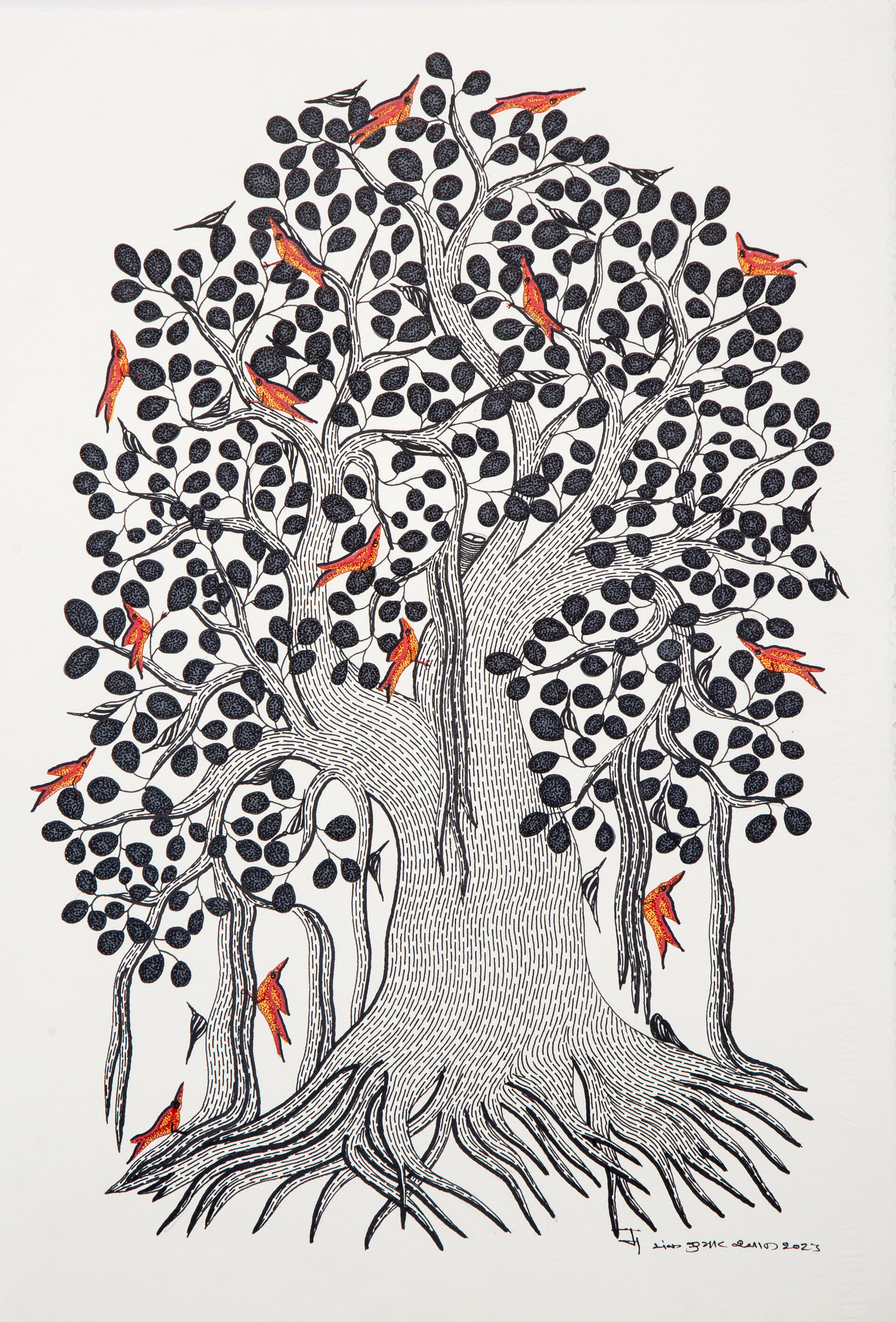

Image

Artwork by Jangarh Singh Shyam

Chapter 2 carries selections from my virtual exchanges with Silvermoon LaRose and Angel Beth Smith, artists from the Narragansett community. LaRose is an artist, educator, assistant director at the Tomaquag Museum and also a public servant; Smith is an artist and a curator. Titled ‘In the Room With’, I deliberately use the preposition ‘with’ instead of ‘for’ or ‘on’, to challenge the academic binary of the researcher and the subject. This is in keeping with my approach to perform research through conversations with people, established names in their respective fields and have been acquaintances for a while now. Positionality is a layered concept, while it situates the researcher in some contexts it also creates distance. ‘With-ness’, I believe, carries the essence of relationships and trust that have been built over time. This chapter is a direct engagement with the artists. They talk about their respective practices, the ways to support Indigenous led projects and institutions, and futuristic visions for their community through the Tomaquag Museum. While the exchange was carried out in a question-answer format over email, you will see some direct quotations along with my voice as I learn from them and make connections with other Indigenous theories.

Image

"Native Blanket" by Angel B. Smith (Courtesy the artist) and "The First Strawberry" by Silvermoon LaRose (Credits: Project Antelope)

Chapter 3 transitions into the art making process in connection with storytelling amongst the Gond Pardhans in India. It carries various subsections that traverse history, legacy, performance and visual art of the community using a combination of textual and web sources. I end with a proposition for curators who want to work with [Indigenous] communities and are looking for ways to incorporate more mindful practices. As an individual outside of the Adivasi community, I believe it is important to remain cognizant of the power dynamics and the limitations that come with it, and yet not be paralyzed by them. It is even more important to continue to learn and incorporate ethical ways that provide the support wanted by the communities and to engage with artistic practices even when, especially when, faced with the untranslatable.

Image

Artwork by Mayank Kumar Shyam

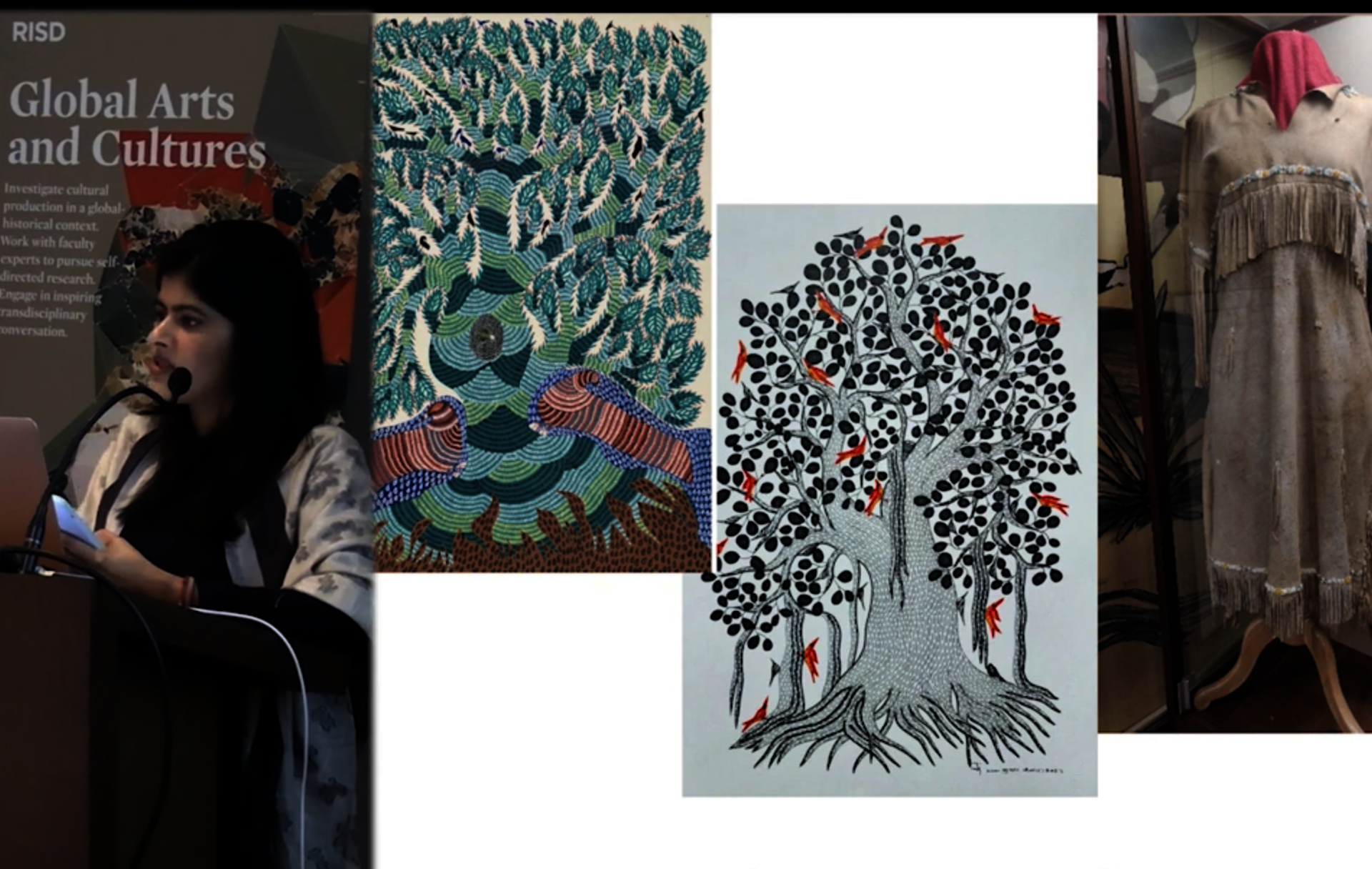

Image

Chhavi Jain presenting her thesis work at the GAC symposium in Dec, 2023

EXHIBITION IMAGES