Ethan Howard

Repair Rolodex

"Repair Rolodex" presents a series of exchanges with strangers met online through email listservs or by word of mouth. Each transaction centers around the repair of a broken thing in return for a trade-in-kind payment. Through the brief relationship between owner and designer, these interactions suggest an object is almost never entirely obsolete despite its perceived obsolescence. At the core of these trades is a grassroots protest of the landfill and a critique of our global capitalist commerce system. The apparent desire for and nature of these trades demonstrates that stories make our objects meaningful. Each interplay studies peoples’ mercurial understandings of value. Each repair celebrates the scars that become evident when an object lives a long life. Each decision is rooted in the belief that small (inter)actions cause large ripples.

Like most people in this project, I met Her on an email Listserv. She responded to my call for broken things with photos of her ex’s chair. “It represents a kind of stubbornness. The chair is solid. My ex was a solid person, a substantive figure." As we sat together and talked, She asked herself a question: "How attached am I to the brokenness of this chair as it represents the brokenness of my ex? How much satisfaction do I get holding onto this as opposed to rewarding myself?"

Image

A Very Special Chair

This chair holds a heavy place in space. Emblematic of a human being sitting there stagnant, limbs detached, it was falling apart at the seams. I silently asked myself: How do you repair a broken body? You use something inert. So, I fabricate something visually and physically non-reactive inspired by that logic. Brass sutures and rods bring back function and highlight what used to be broken.

Image

Detail: A Very Special Chair

She told me, "These chairs come from a house on the shore on the ocean in Rhode Island. I don’t know how old they are. Early twentieth century, maybe older. They’re so delicate and interesting. But the chairs were completely unusable because the seats were gone." When I think of the ocean and weaving together new seats, I think of something fibrous and malleable. I wondered how plausible it would be to fabricate new seats with beach grass or kelp. Doing so would be more meaningful and local than buying pre-woven cane from an online retailer. A few weeks after receiving the chairs, I reached out to a local kelp farmer and purchased five pounds of fresh sugar kelp. Though I’ve never worked with this material, bioplastic seemed like a reasonable way to bind the kelp blades together and preserve their structural integrity.

Image

Kelp Chairs (re-caning)

As I wove the seats together, my hands became sticky with salt. During the hours-long process, I filled my mouth with handfuls of the kelp blades that were too short to use. Briney. Bioplastic painted between each layer welds the kelp together and creates a durable bond. When you can eat the same material you’re working with you realize how interconnected everything could be. When your chairs smell like the ocean for weeks, you realize how lovely it is for your objects to literally embody their story. When you think regeneratively, you push your design decisions to accommodate a future reliant on stewardship and ecological engagement.

Image

Detail: Kelp Chairs (re-caning)

This garment was not visibly broken, reinforcing my philosophy that a collective panoptic definition of brokenness cannot exist. What needs repair can only be determined on a case-by-case basis. While I interviewed her, She told me, "On the jacket, there are very thick decorated knobs as the buttons. I don’t like my clothes to be too flashy. Not only that, but the buttons aren’t functional. The other side of the jacket is sewn through, and the holes are closed with a stitch.” As we spoke, it became clear how closely connected she was to her home in Galicia. I asked her about it: Could you tell me more about where you’re from? What food do you eat there? What’s popular? Her response inspired how I repaired the buttons on this jacket.

Image

Buttons

She said, "We have these things that live on the rocks and are local to our area of Spain. They're very small. My brother and I would get a plastic bag and fill it with as many as we could, wiggling them off the rocks." She's talking about Periwinkles. "Most of the clothing I buy is from Spain because it's from people that I know who are making it. I like knowing where the materials are sourced." Inspired by these versions of hyper-locality, I went to the RI coast and found a beach with plenty of Periwinkles. There, I picked them and brought them back to Providence, where I cooked and ate the snails (drenched in butter and garlic) and ground the shells into a powder. Using this powder and a resin substrate, I cast the Periwinkles into six new buttons.

Image

Detail: Buttons

“I got this plate when I was a junior in college. My roommate entered us into a contest which we won. Each one got $2,000 to West Elm. I bought these plates. Since then, I always moved into places where people had plates. So, I never used them until this year. Recently, my sister came to visit. I was overwhelmed by the prospect of being a host. So, when I went to wash the dishes, I dropped it, and a piece fell off. I thought it broke so perfectly. It’d be a waste to throw it away. But it’s going to take me years to get around to fixing it." Like many of us, She finds sentiment in objects that feel meaningful to her. But this plate was definitely not one of them. "They do not mean much to me. Its weird though; I’m not... not a sentimental person.”

Image

Meaning (full/less)

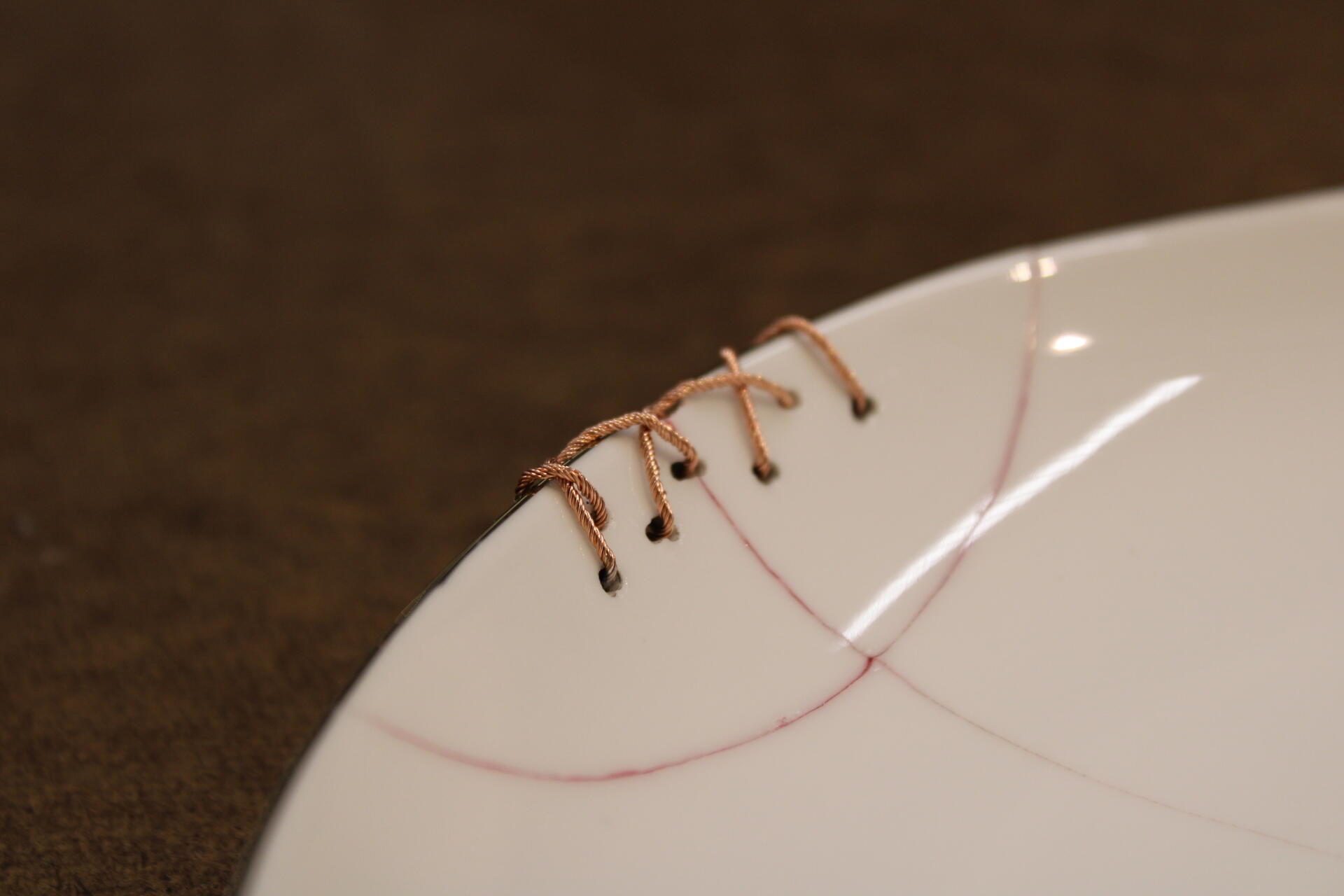

This plate had no initial perceived value. So, the process of repair became threefold: Bringing it back to a functional state; making it more valuable than before; conducting the repair with a cheap material that would inflate in value over time. The solution was to strip the PVC coating off an electrical wire to extract the copper inside, then wind the wires together to make a braid. By stitching the broken pieces together with a finite material, the plate’s literal value will continue to increase over time. Its environmental footprint stayed small (using found wire), while the footprint the object holds in Her life took a leap forward.

Image

Detail: Meaning (full/less)

EXHIBITION IMAGES