Website

IG: sumkrishna

ABSTRACT

Around the world practitioners and researchers are working on new material systems and technologies that center new ways to build. In this age of information, there are countless design frameworks, tools, machines available to us. We are a part of the fundamental shift in architecture that involves new modes of production and new material systems that redefine our role as architects. We have a role in addressing the context of each project, using architectural elements as tools for negotiation and consensus to build stronger communities. How can architecture contribute to improving global labor conditions, instilling dignity in manual labor, dismantling economic systems that mandate problematic class distinctions, and promoting social and environmental justice?

The project titled breaking the mold: a journey of the brick investigates the nature of global practices in architecture and construction. It examines the ethics of production and consumption of materials, foregrounding the inequities that exist within our daily practices. I wanted to understand through this project the relationship of labor to specific means of production and to embody the engagement of people with the material.

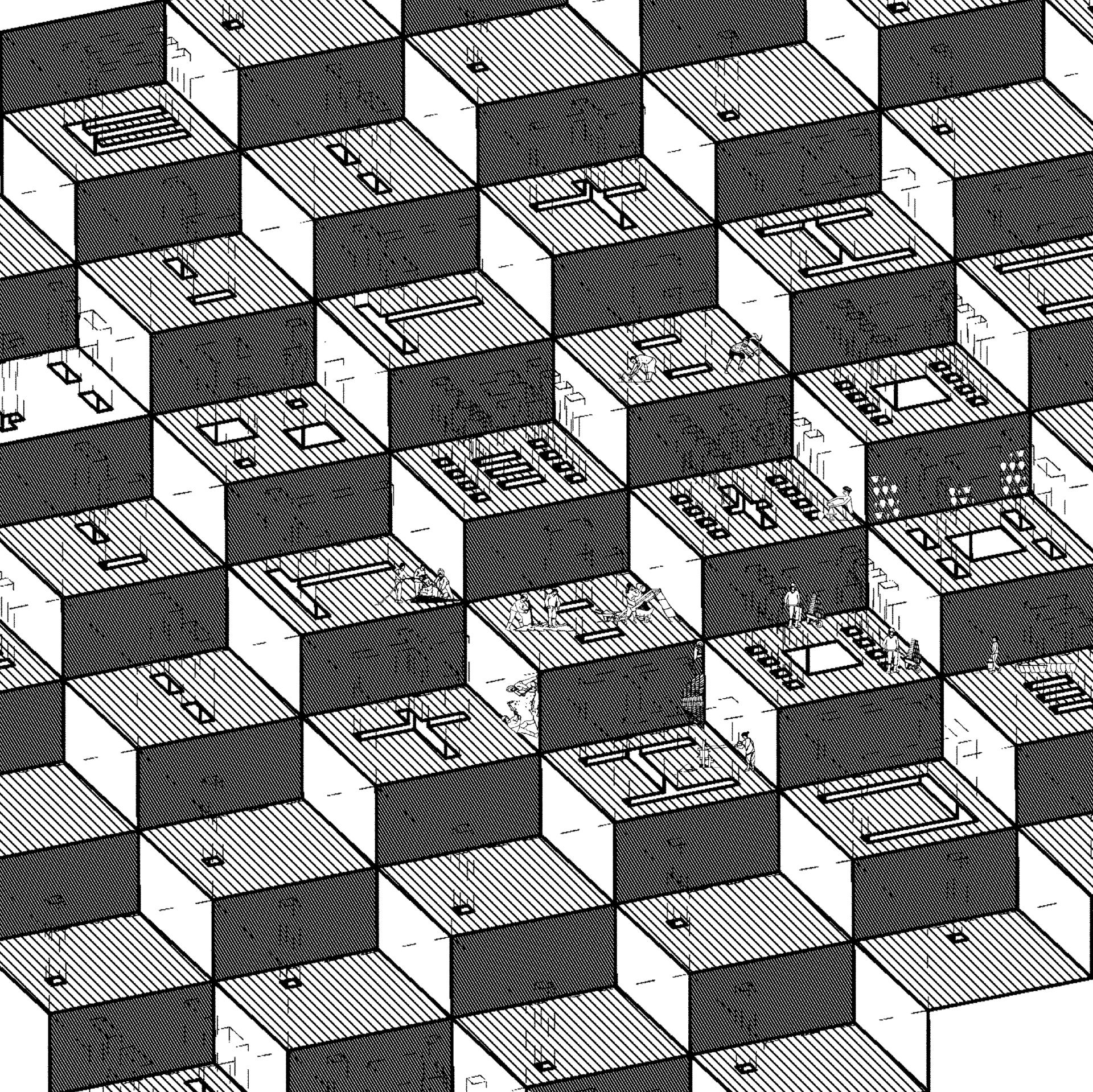

This project critically examines architectural drawings as a form of representation capable of fostering revelatory dialogues between analog and digital content. It draws from historic examples of drawings by the likes of Piranesi, Choisy, and Boullèe to create a form of digital representation that communicates architectural intent. The drawings in the project choreograph a critical dialogue between the digital pixel and the analog brick: both are basic elements operating within the larger economies of digital images and architectural construction; both are capable of world-building through known logics of aggregation; and both contribute, through recombination, to elaborate and sometimes ornamental patterns.

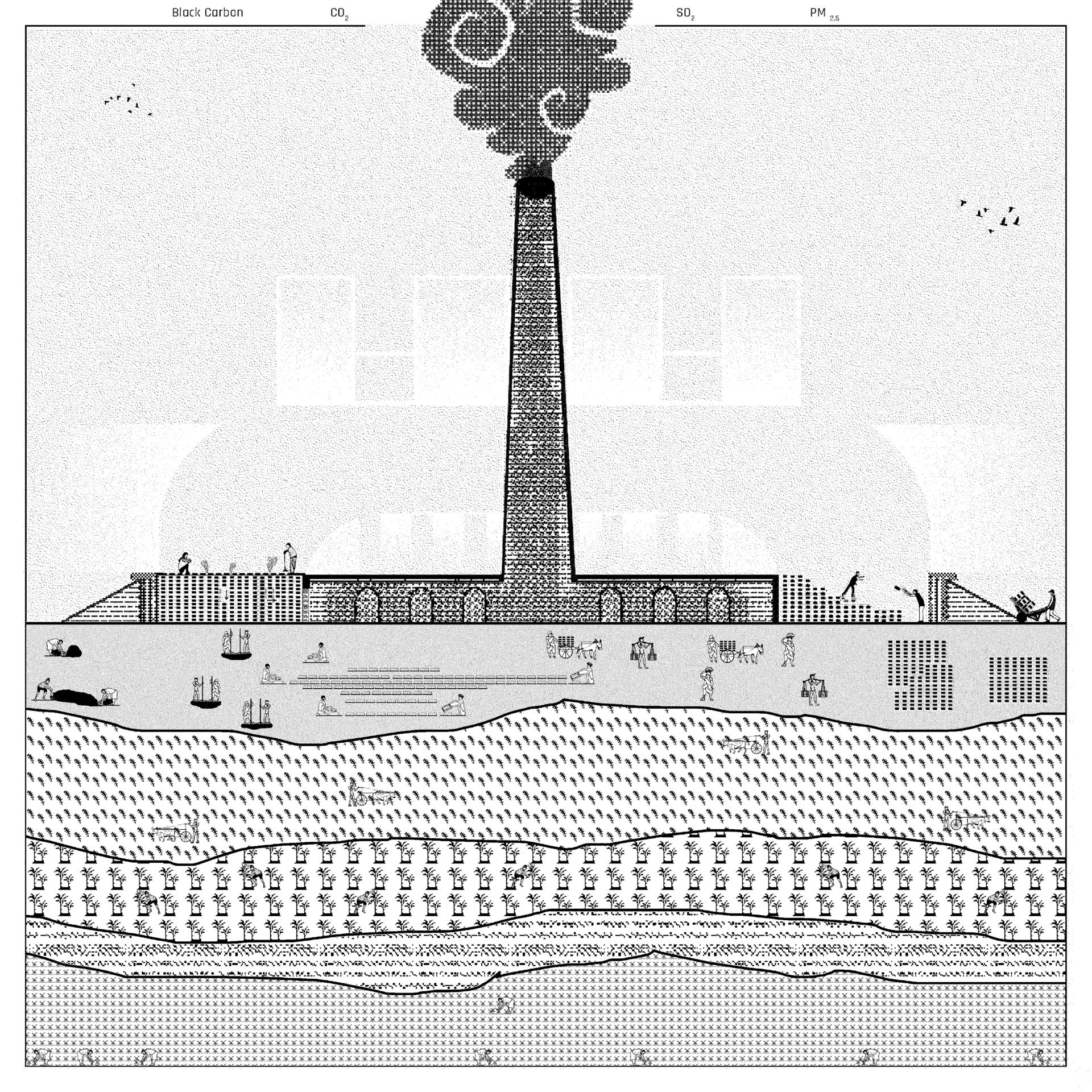

1px = 1km

At this scale, we can develop an understanding of the regional ecology that my thesis engages with. The research examines the process of industrial production of bricks in India. The Indian subcontinent produces about 13% of the global supply of bricks which adds up to about 250 billion bricks per year. This estimate comes from a workforce of about 10 million people working across 35000 kilns in one of the largest unorganized sectors that needs attention. Within a 3-mile region of study, I identified 167 Kilns that employ about 8000 migrant workers seasonally. They are also one of the largest polluting industries consuming about 35 million tons of coal annually.1

Image

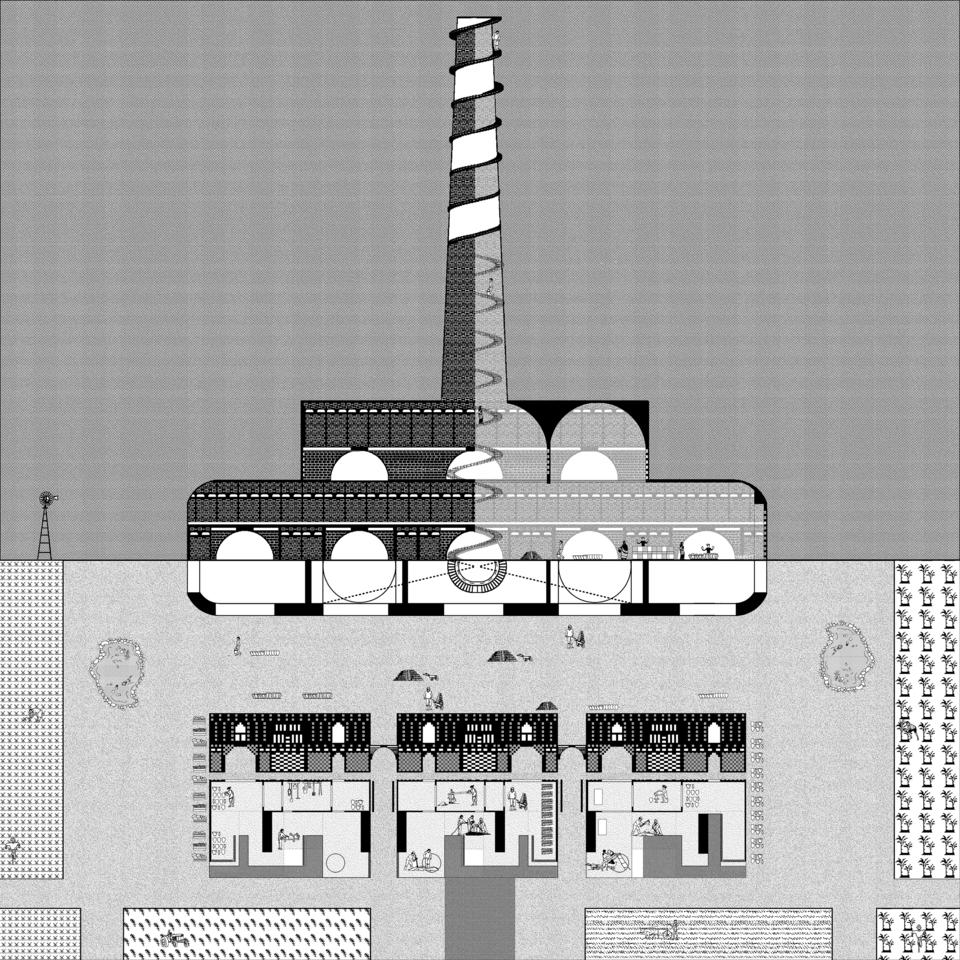

The Fixed Chimney Bull Trench Kiln

Image

1 px = 1 meter

This drawing illustrates the various processes in and around the kiln site while also indicating the supporting activities that the workers engage in such as the farming of Sugarcane, Wheat and Rice. The brick production process requires a large amount of physical labor through the process of digging, pudging, and molding the bricks before they are loaded in the kiln. The Fixed chimney Bull trench Kiln is a continuous firing kiln that allows the kiln to operate across the season without the need to restart the firing process repeatedly. The loading and unloading of about 5000 bricks a day are typical at a kiln worksite. Workers are recruited by a contractor who offers them credit in exchange for work at the kiln sites. They are recruited as family units who work 6 days a week and have a monthly income of about $140 for the entire family as compared to a student in an internship who earns about the same per month. To maximize profit margins, the kiln owners do not provide tools and machinery to make the production process less laborious. This exploits the workers physically and financially, putting them into multi-generational debt bondage.

A new ecology

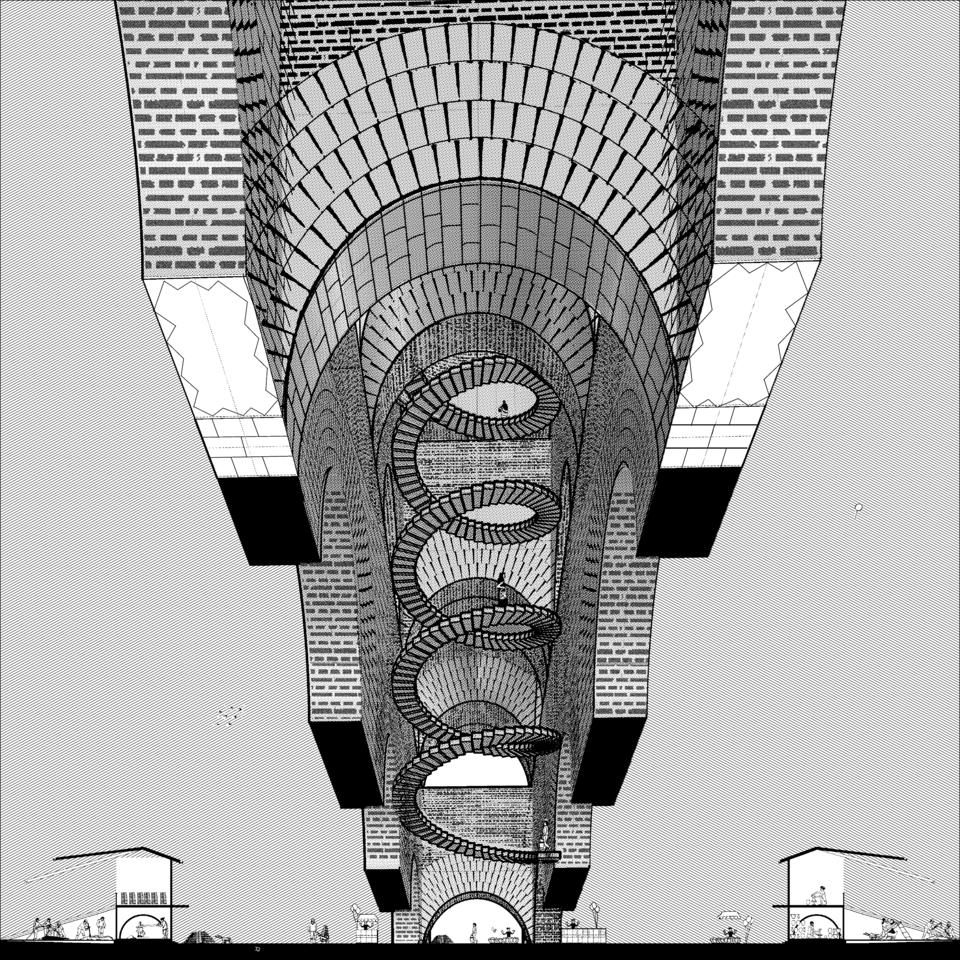

1 px = 1 ft

The legacy of colonialism in the region is preserved in its systems of measure. Highly educated engineers and architects communicate their designs using the metric system, whereas the uneducated physical laborers convey their intentions to the construction industry through the imperial system of measure. Therefore, there is an implicit hierarchy between architectural design and construction that preserves classism by perpetuating the hegemony of imperial measure, while subjugating the laborers to it.

The revision in my thesis construction starts with the creation of vocational studios which are intended to empower the worker on-site along with a central marketplace. It involves the redevelopment of the existing kiln ecology to create a community of makers. These studios are designed to be multifunctional spaces that can act as independently-run artisan studios or can be interconnected to create larger studios. To allow the workers to engage in commerce with the consumer directly, the kilns center structure called the Miyan was redesigned to be a double-height marketplace for the community. The central chimney is designed to become an observatory tower for the local community; it also acts as a symbol of the changing economy.

The brick’s eye view. It is a 2-point perspective collapsed onto a sectional elevation to allow the brick to be in dialogue with its maker. The brick’s eye view represents the weight of the brick wall, informing the laborers about how to engage with the construction of the masonry in the drawing.

1px = 1 inch

Image

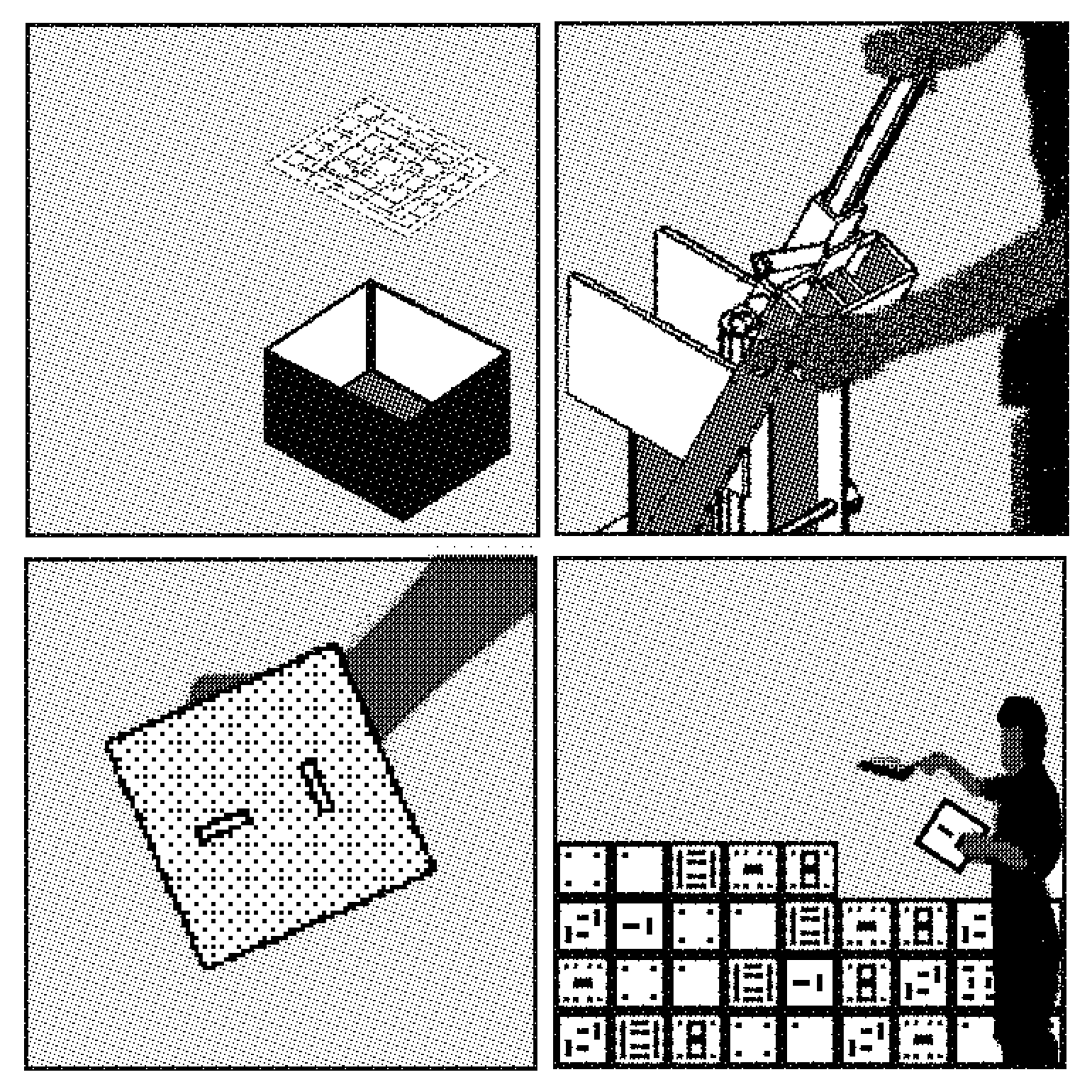

▲ In this process, I started with a 12 x 12-pixel grid with a bounding box. I then started to depict solids and voids through the pixel to create interesting patterns that can create a new geometry of brick jali that are informed by pixel grids. The use of jaali bricks creates an interesting relationship between the wall and the street but also allows ventilation and play of light and shadow within the spaces. The jaali brick also has cultural significance within the region.

Image

▲ Further identifying tools to make the process more economically feasible. By appropriating existing tools, the brickmaking process can shift from an industrial to an artisanal practice, empowering the brickmaker. Retooling the CINVA-RAM press originally designed in Colombia, to accommodate molds of different shapes.

Making Bricks

In this process of brick making, I wanted to limit my access to machinery to embody the ethical relationship between material, tools and the human body that are appropriate to this region.