Image

Thesis Statement

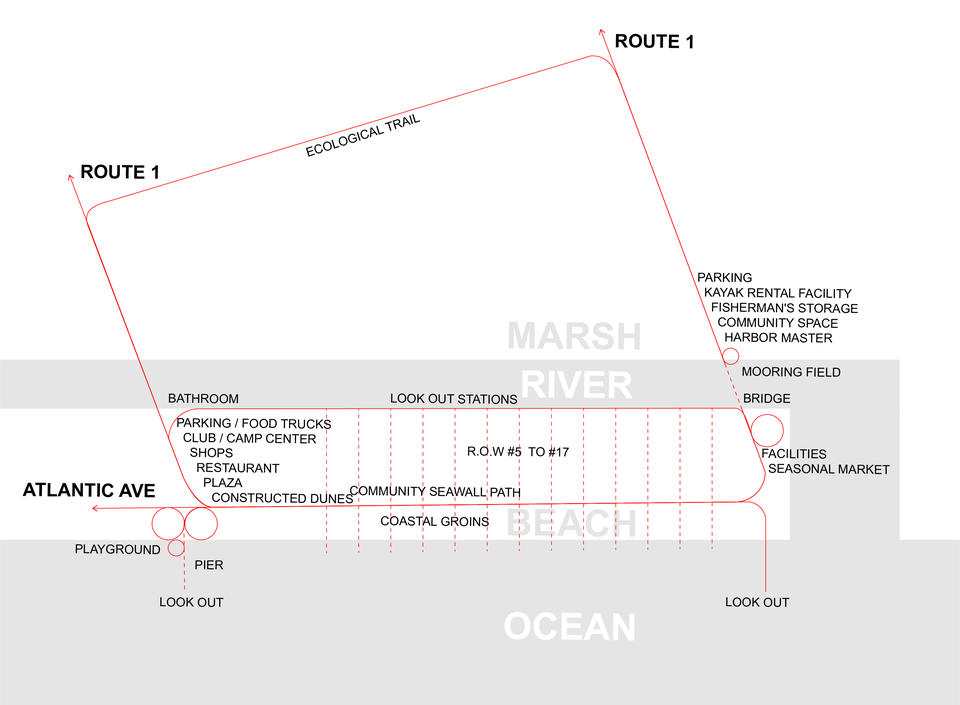

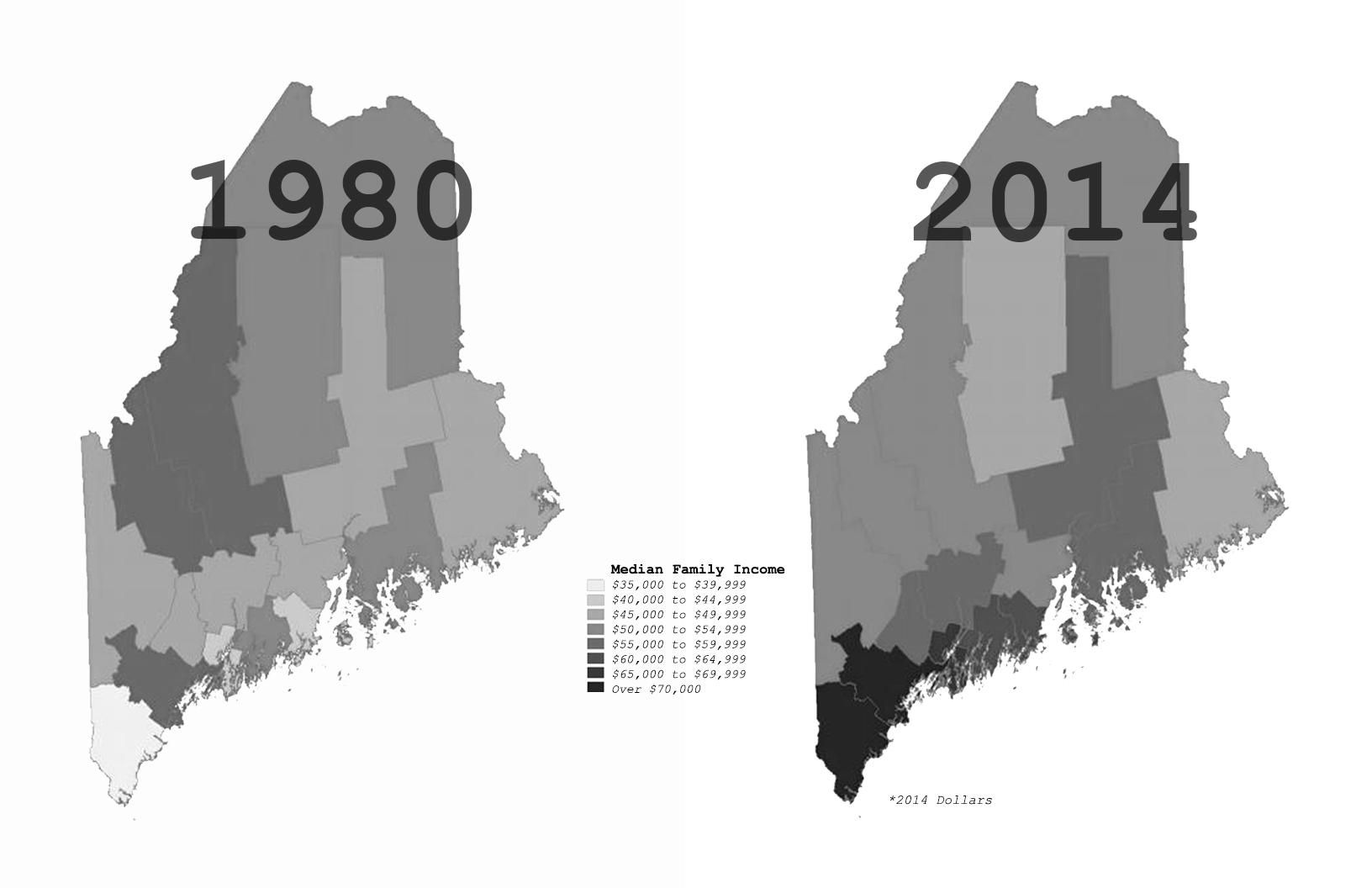

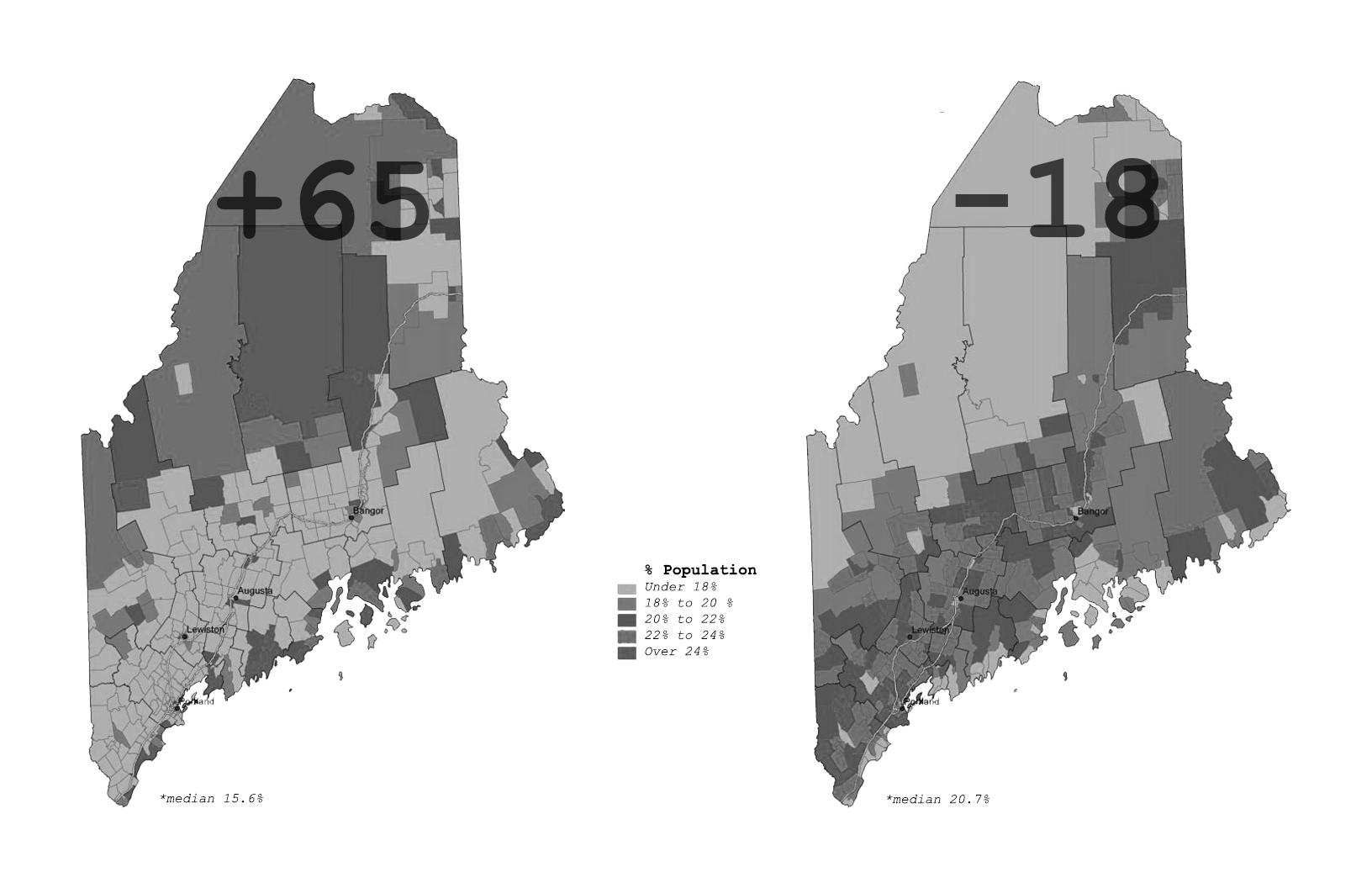

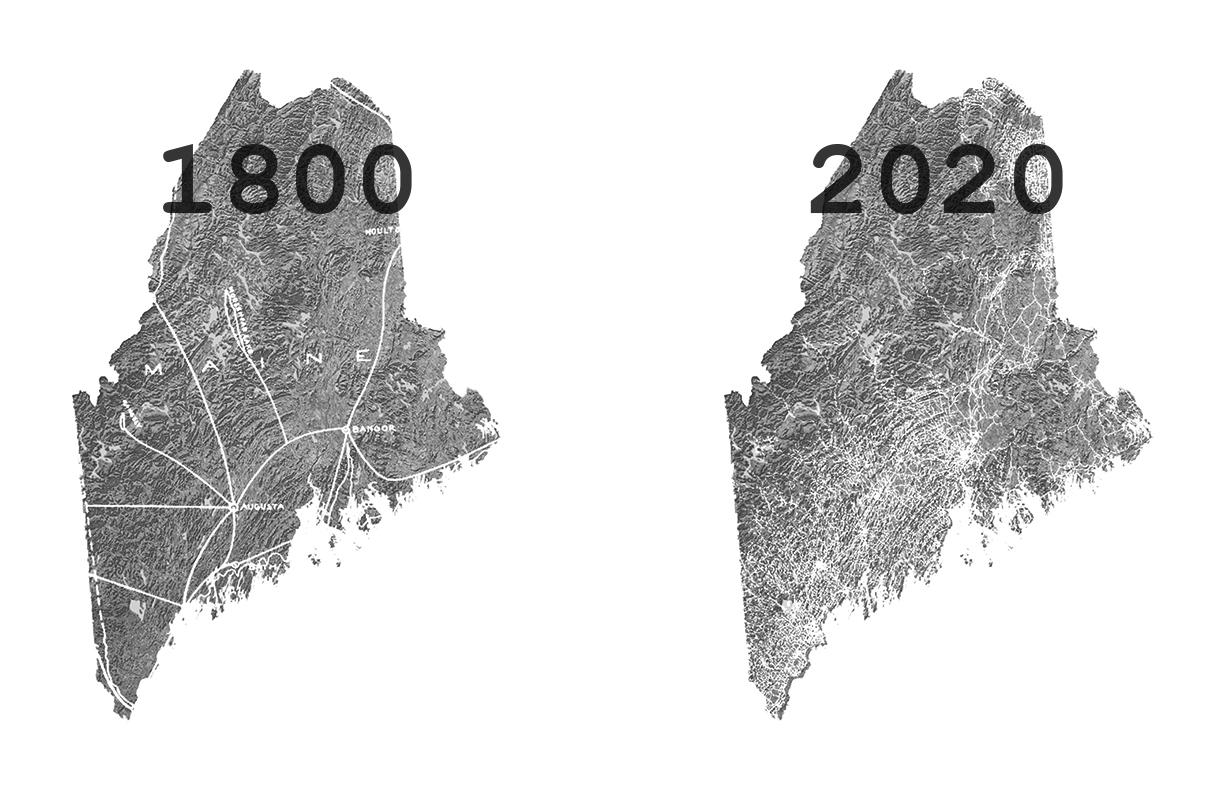

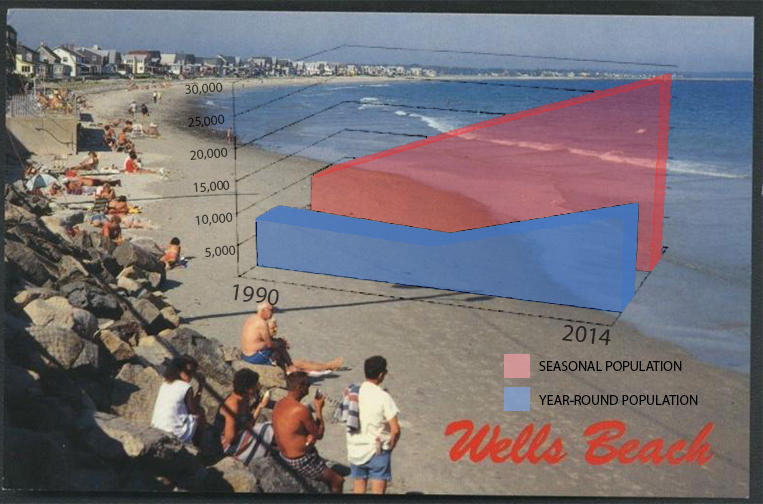

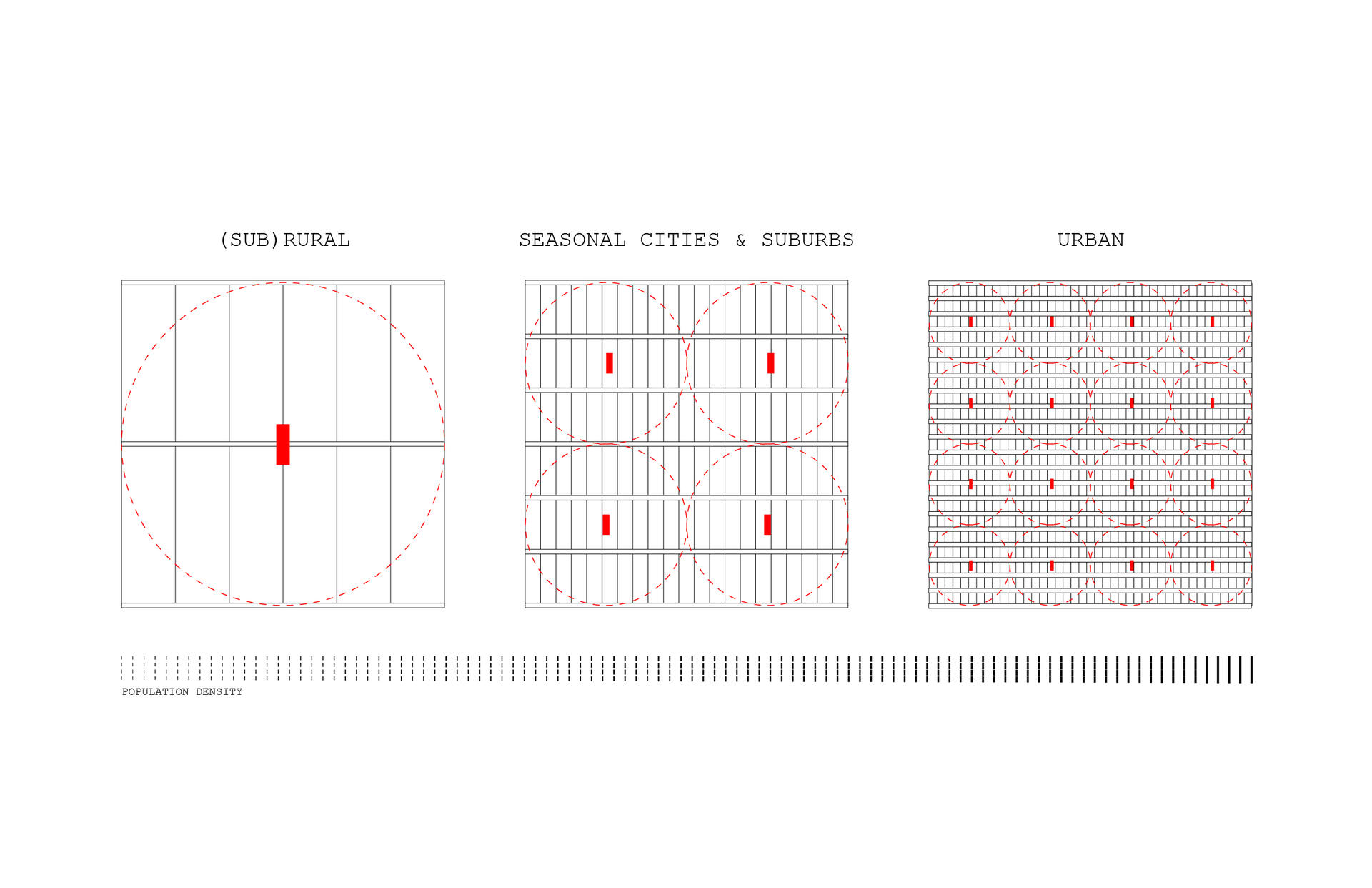

The tourist economy in Maine, while profitable, has been a catalyst for the removal of local communities on the coast through the privatization of ecosystem services. Inclusive master planning that reconnects Maine’s coastline to its upland areas in the southern beach region will restore a lost local and working class identity. This proposal enables year-round and flexible programming and stewardship of the natural environment, and challenges the current model of commodification of a landscape and its people. Furthermore, celebration of the right of way to ecological systems and development of supporting markets for both the working and playing communities of the vacation landscape benefits the modernization of the Maine identity and diversification of its labor force. Maine’s economy in the past relied heavily on timber harvest and manufacturing for paper, an industry that existed within the arcadian image. In the late-1970’s Maine pivoted toward a tourism, hospitality and real estate centric system. A now near 11.5 billion dollar industry that operates only six months out of the year. As a result Maine density has moved to an aging and unaffordable southern coastlines with relatively little economic activity generated in the center or northern areas of the state. Out-of-state ownership has led to part-time communities and the polarization of the working and leisure populations. Southern Coastal towns like York, Kennebunk, and Ogunquit are unable to execute comprehensive master planning that seeks to stabilize year-round communities in the face of annual winter abandonment. The beach community of Wells is one such center for tourism where coexistence between the two communities' use of the surrounding natural and built environments would create a model of holism in a seasonal city typology.

Tertiary strategies that work in tandem with architectural intervention to unbind the privatization of public resources are coastal devaluation models, creation of conservation easements, and mixed use zoning. Additionally, coastal categorization as vulnerable to climate change and past developmental negligence limit the use of a landscape and should be challenged by building more responsibility and with appropriate materiality. The architect’s role in the seasonal city is to facilitate the relationship between the people who use the built environment and instances of shared experience to nature for all. The institution of perpendicular community programming repairs the delamination of the Maine coastline and restoration of agency on the shore for both the tourists and the working class.

A MORE WEALTHY COAST,

Image

AN AGING COAST,

Image

A MORE DIVIDED COAST.

Image

VACATIONLAND

Image

TWO COMMUNITIES

Image

SEASONAL CITY TYPOLOGY

Image

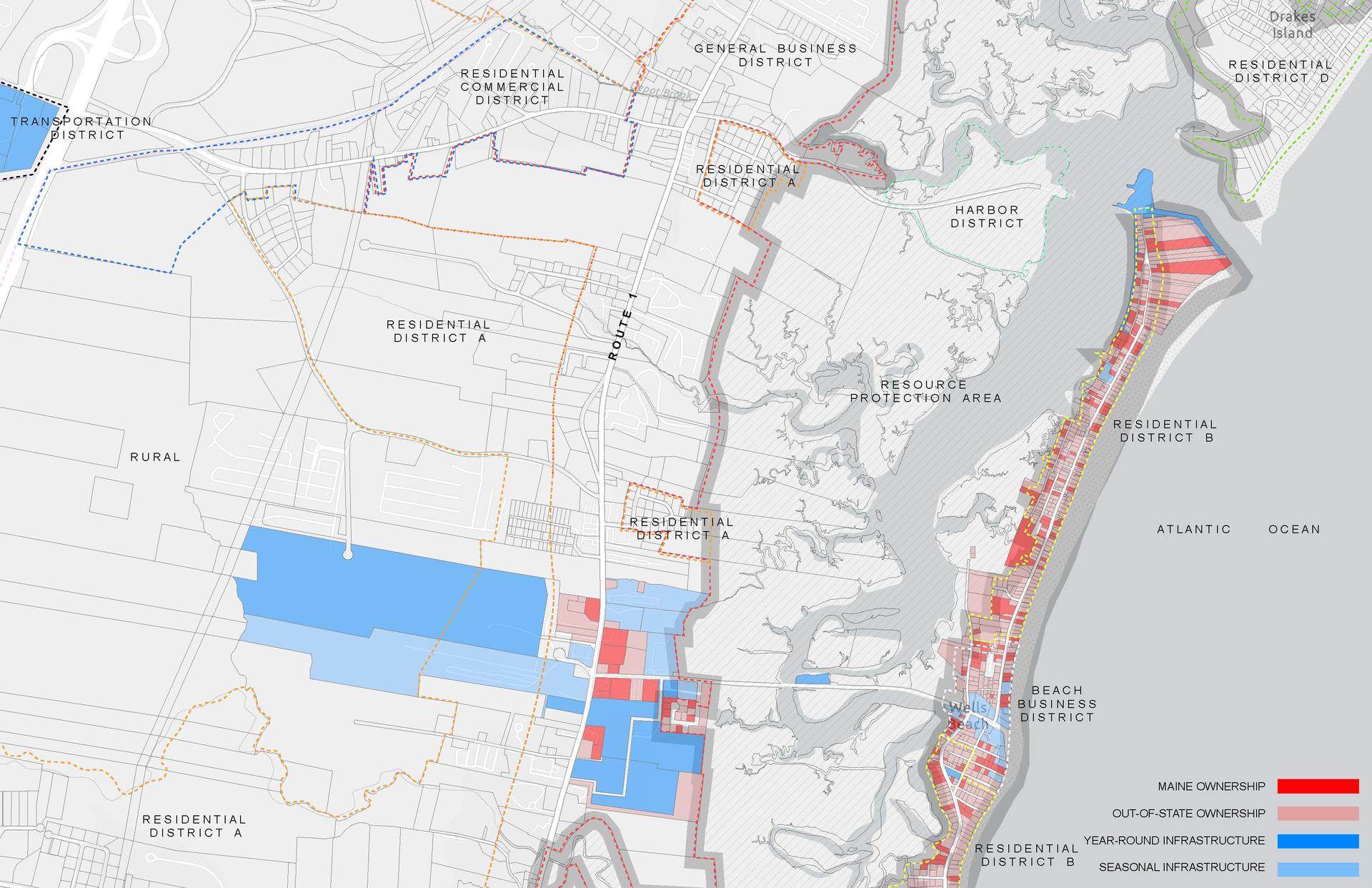

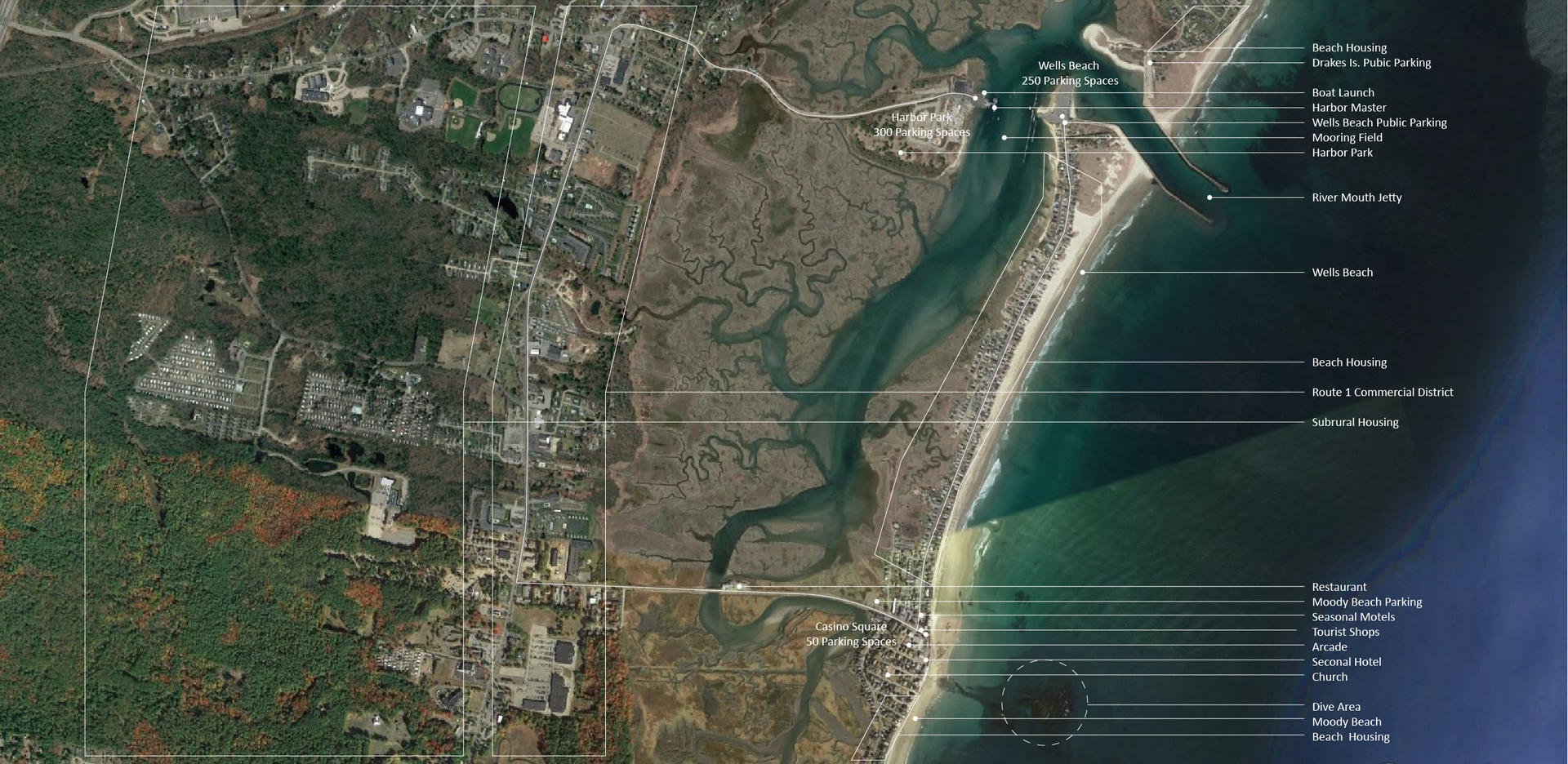

MAPPING THE SEASONAL CITY

Image

EXISITING WELLS BEACH PROGRAM

Image

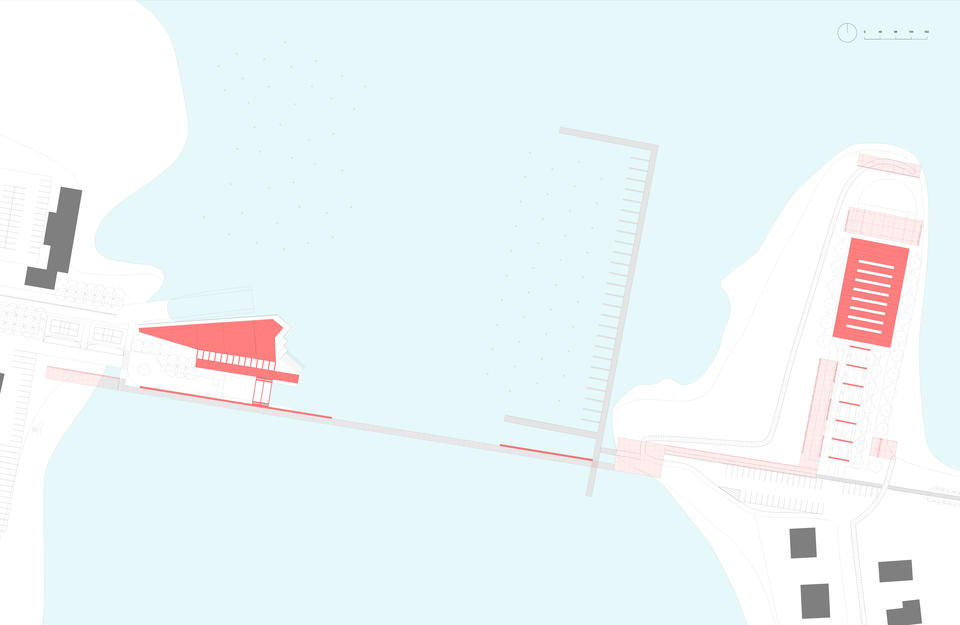

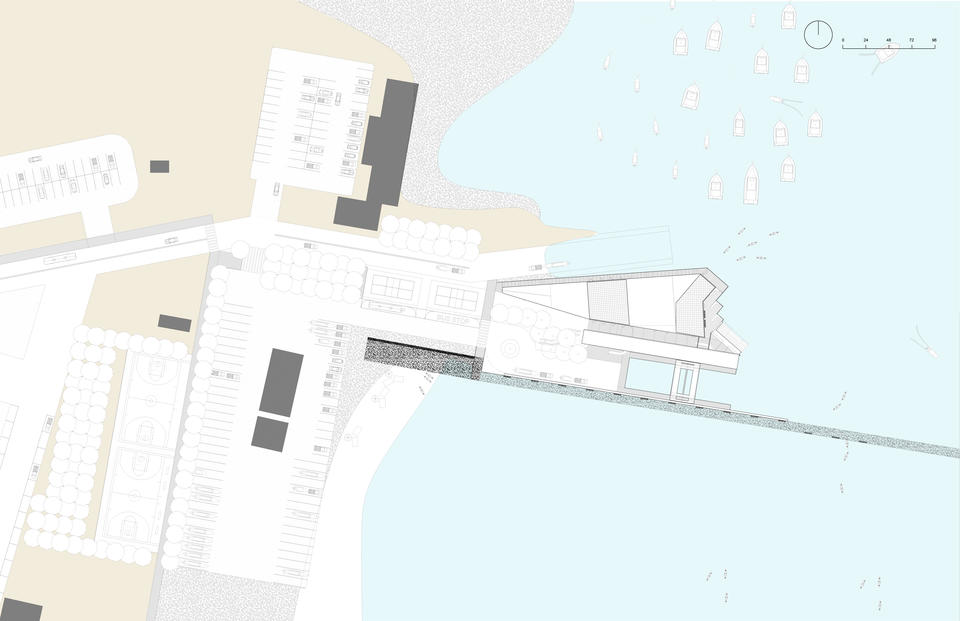

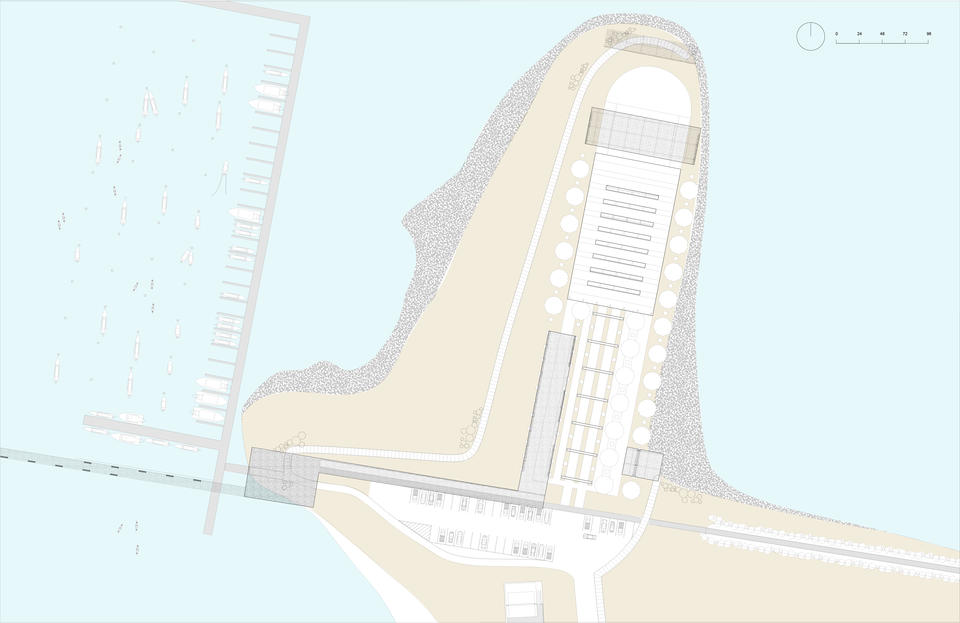

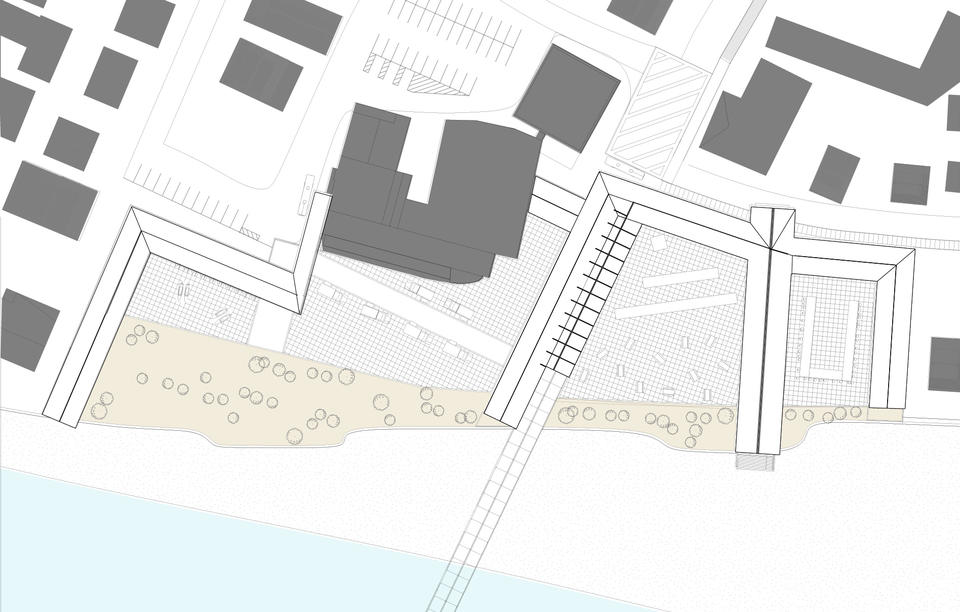

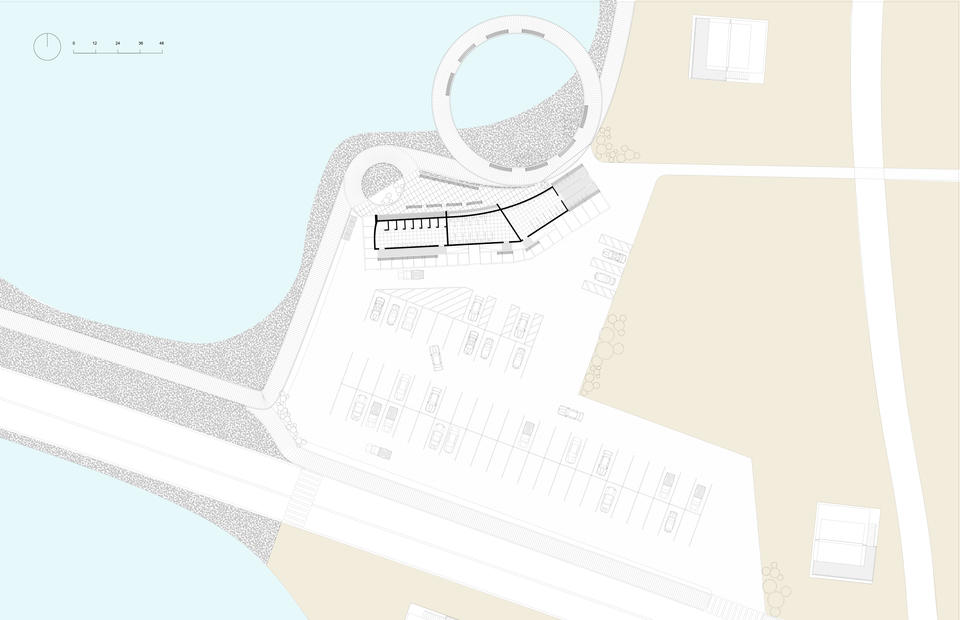

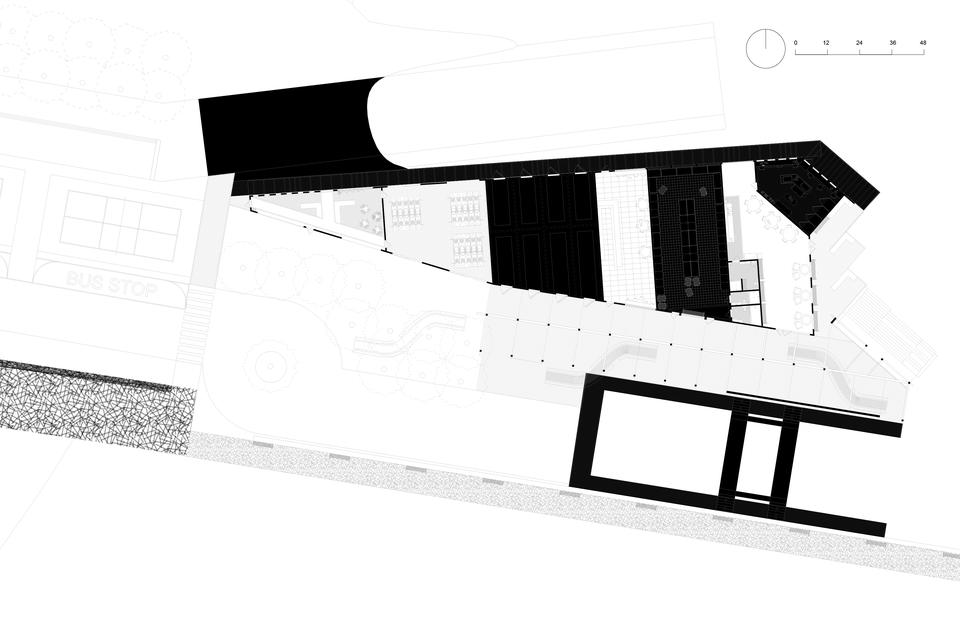

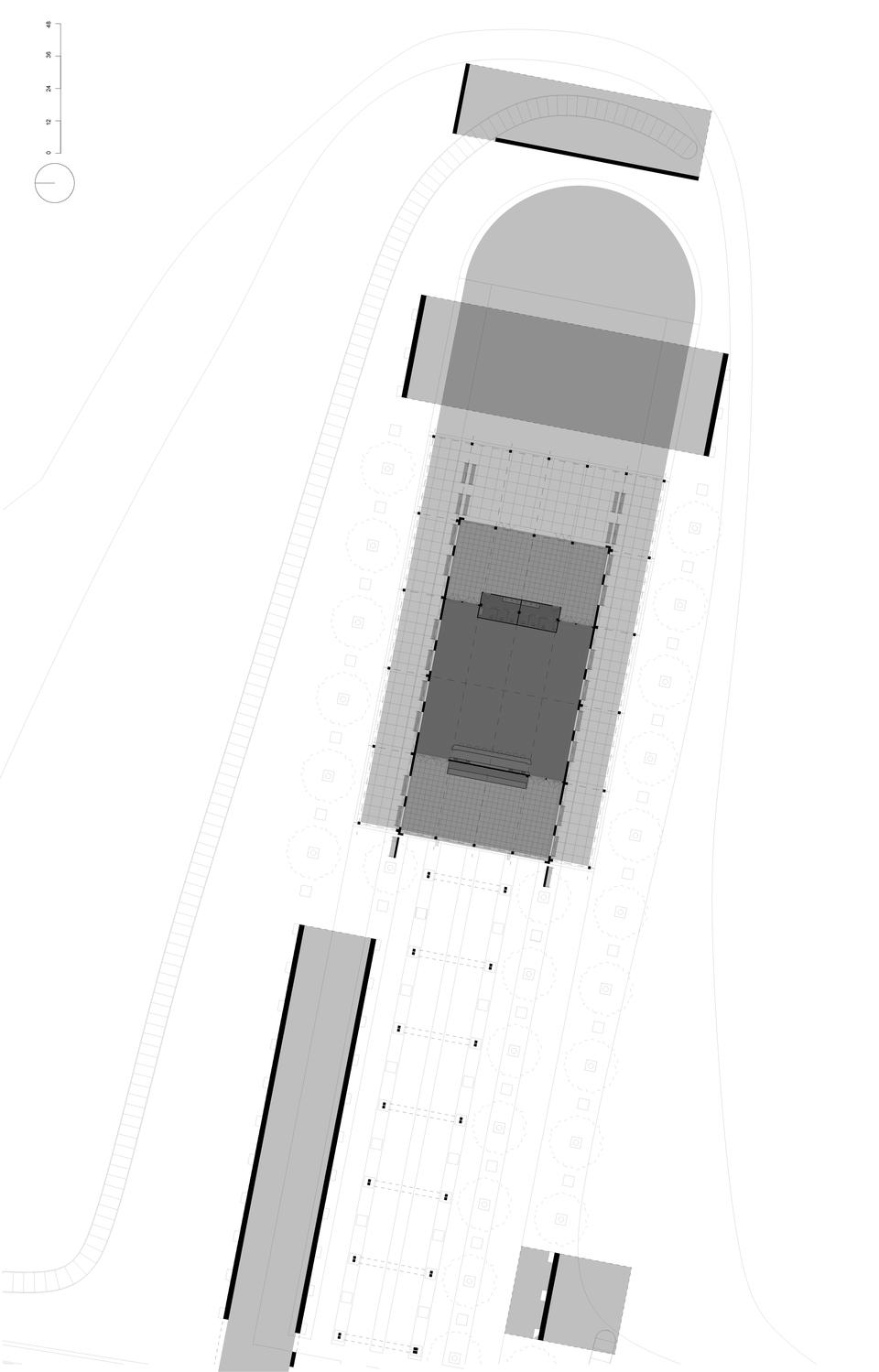

MASTER PLAN DRAWINGS

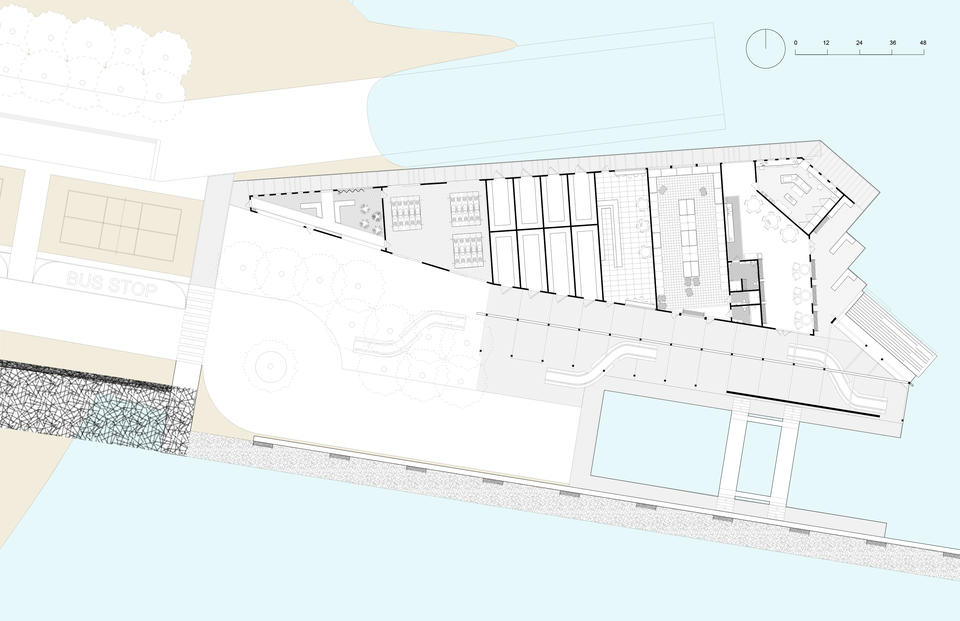

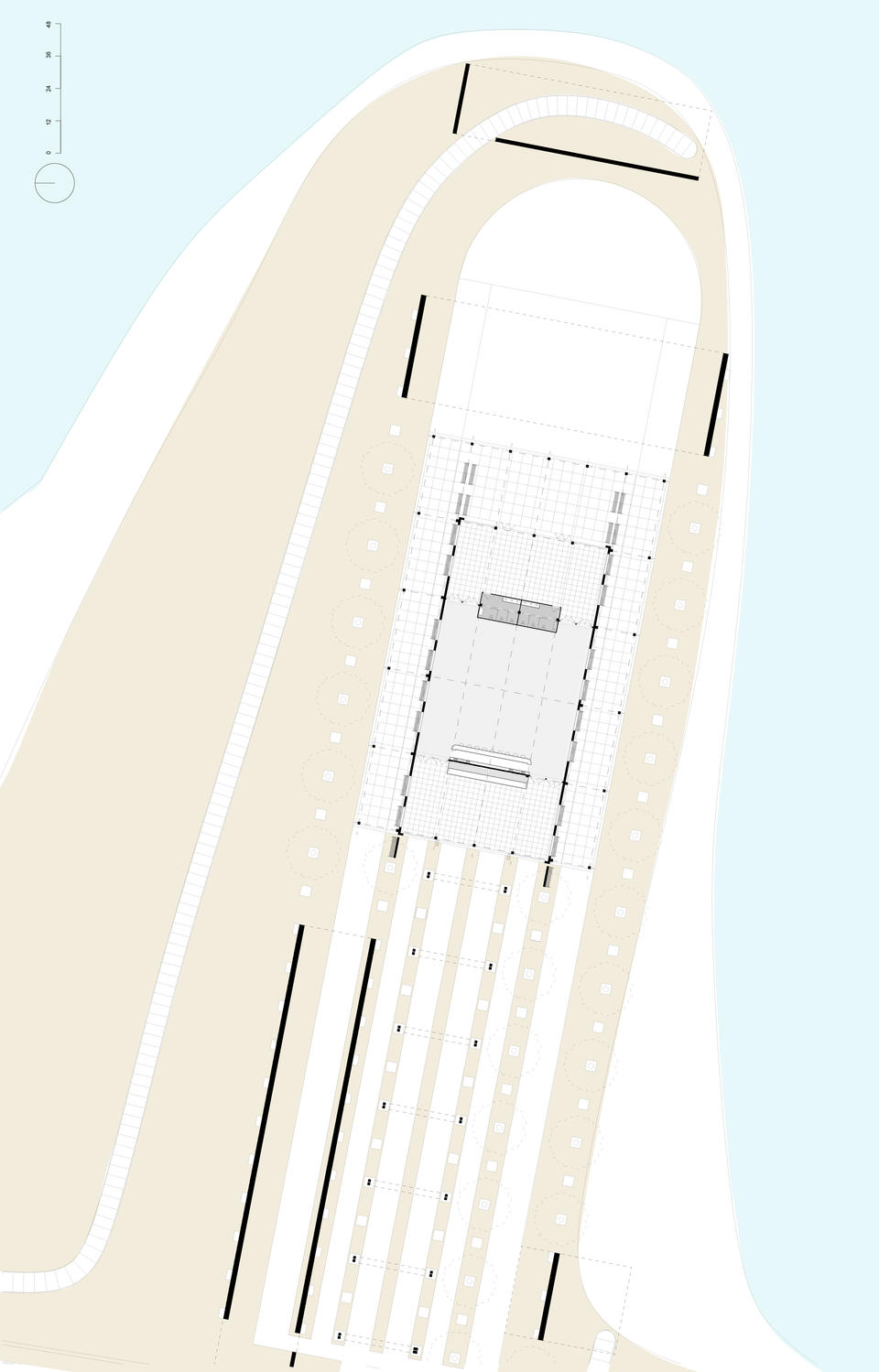

SITE PLAN DRAWINGS

PLAN - SECTION DRAWINGS

CONCEPT DIAGRAMS

PERSPECTIVE RENDERS

Image

CONCLUSIONS

Ecotourism more generally can be defined as tourism that supports the conservation of a threatened environment. The threat to many coastal environments is the privatization and preservation that hinders a connection to nature for its residents. How can models of sustainable tourism be applied to developed country’s subrural landscapes? Additionally, questions of modernization and a diversified economy drove this proposal. How can heritage and access to modern industry not compete with one another and create opportunity for all levels of income to live on the coast. Lastly, what are models of shared ownership of ecological spaces for both livelihood and leisure? Can the future of shoreline development embody a conservation easement as the basis of design for all?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Department of Administrative and Financial Services: State Economist, State of Maine. Economics & Demographics. http://econ.maine.gov/index/build.

Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment. “Coastal Land Use and Development.” Gulf of Maine Association, June 2013, gulfofmaine.org/public/state-of-the-gulf-of-maine/coastal-development/.

J. M. Omernik. Ecoregions: A Framework for Managing Ecosystems. The George Wright FORUM. Volume 12, Number 1. 1995. http://www.georgewright.org/121omernik.pdf

Lamber, Keeley-Anne. Wells Maine Assessor Map. https://www.axisgis.com/WellsME.

Maine Center for Economic Policy. The State of Working Maine 2017. https://www.mecep.org/maines-economy/sowm2017.

Maine Department of Economic and Community Development. Maine Economic Development Strategy: 2020-2029. 2019, www.wellstown.org/DocumentCenter/View/4048/Maine-Economic-Development-S….

“MAINE: The Farnsworth Collection.” Farnsworth Art Museum, 24 Feb. 2020, www.farnsworthmuseum.org/exhibition/maine-the-farnsworth-collection/.&n…;

Pollard, J.A. Polluted Paradise: The Story of the Maine Rape. Lewiston: Twin City Printery, Inc., 1973.

RISD. Fleet Library | Rhode Island School of Design, 2020, library.risd.edu/.

The Marine Law Institute, University of Maine School of Law. “Public Shoreline Access in Maine: A Citizen’s Guide to Ocean and Coastal Law.” The University of Maine Cooperative Extension, Sept. 2004, www.mainehealthybeaches.org/documents/pubacc04.pdf.

The University of Maine. “The Maine Question: Conversations Important to Maine and Beyond.” The Maine Question, 10 Sept. 2020, umaine.edu/podcasts.

Town of Wells. “2016 Comprehensive Plan Update.” Town of Wells Vision for the Future, 2016, www.flipsnack.com/sbelanger/inventory-table-of-contents/full-view.html.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Ecoregions of North America. EPA Official Website of the United States. Accessed august 23, 2020. https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions-north-america.

Town of Wells: The Vision of Our Future, 2016 Comprehensive Plan Update. https://www.flipsnack.com/sbelanger/inventory-table-of-contents/full-vi…

Wallace, David Foster. “Consider the Lobster and Other Essays.” Consider the Lobster, Boston, Back Bay Books, 2007, pp. 235–54.