Image

Xin Wang

Death Space

The changing discourse of death: how to design contemporary immortal funeral practice

ABSTRACT

My thesis seeks to design my grandfather’s cemetery to regain a piece of my personal memory. It also seeks to situate this issue in the contemporary context of the pandemic, which helped inspire my topic. I started my thesis in a very turbulent year. I found myself missing family members far away on the other side of the earth.

How are they doing now?

I suddenly missed my Grandfather’s village, which I had only visited once a year prior to the great pandemic. My Grandfather passed away when I was very young. I get along well with my Grandmother, but I rarely hear the story of my Grandfather from my Grandmother, and his photos have always hung on the wall of the living room, which conspicuously reminds me of his look. Maybe my Grandmother misses him the same way. When I went back, that photo was no longer there. Does that mean this memory over?

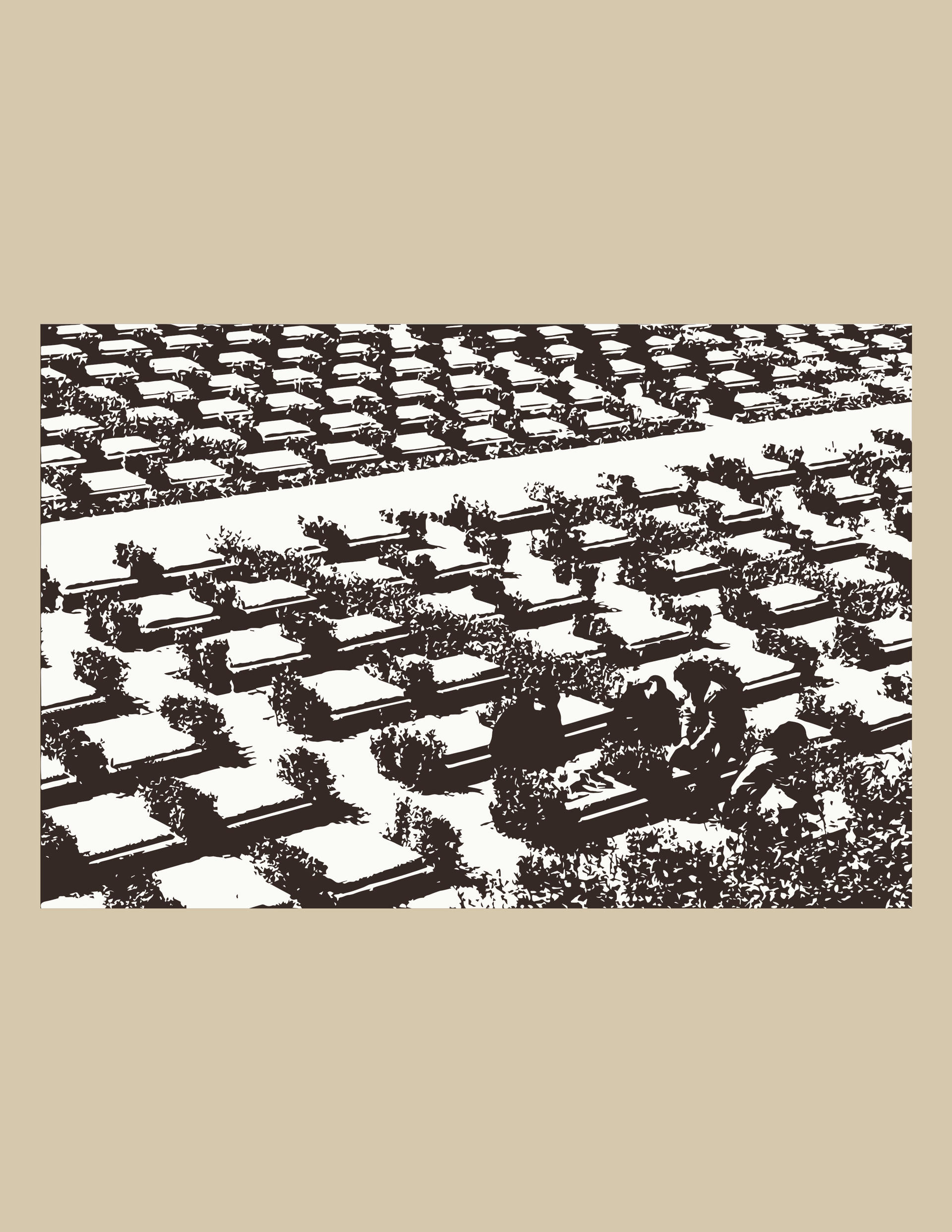

I didn't remember my Grandfather’s Cemetery because I only participated in his funeral ceremony. The news broadcasts that public cemetery prices are getting higher and higher. Can the pain of losing a loved one be measured by money? No one really mentioned this pain.

I started to reflect and decided I want to tell this story by rebuilding my Grandfather's cemetery.

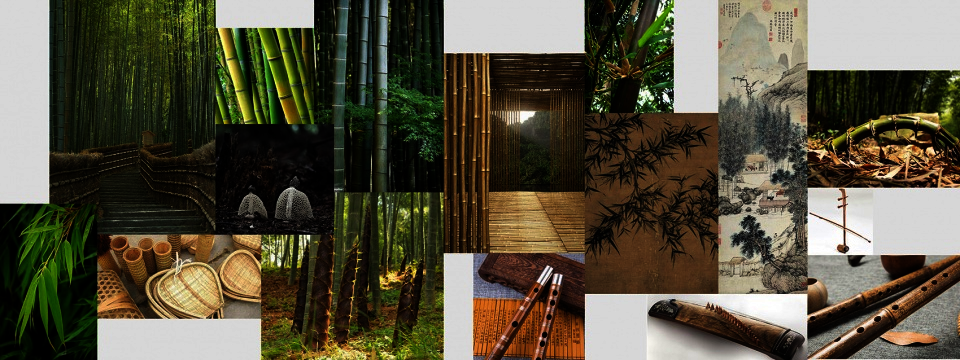

Bamboo forest concealing Grandfather cemetery

Image

LIFE AND DEATH

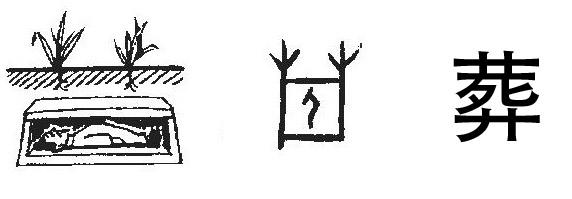

China is a country with deep roots in Confucian culture. Funeral practices are inseparable from the Chinese viewpoints of life and death. The significant differences in funeral rituals between the East and the West are based on these two cultures’ competing interpretations of death.

Chinese people believe that when people die, they should be buried in the ground which will lead them to another spiritual world and that the living should no longer disturb their space. As such, the tombs are always hidden deep underground, mirroring the ancient Chinese character diagram seen on the right, which shows grass on the ground on top of a body buried in a coffin underground.

Image

People often attach importance to convey ideas of life and death in China; rituals form the roots of funeral practices.

The Right image shows that “Koutou” one of the important Chinese funeral rituals

Image

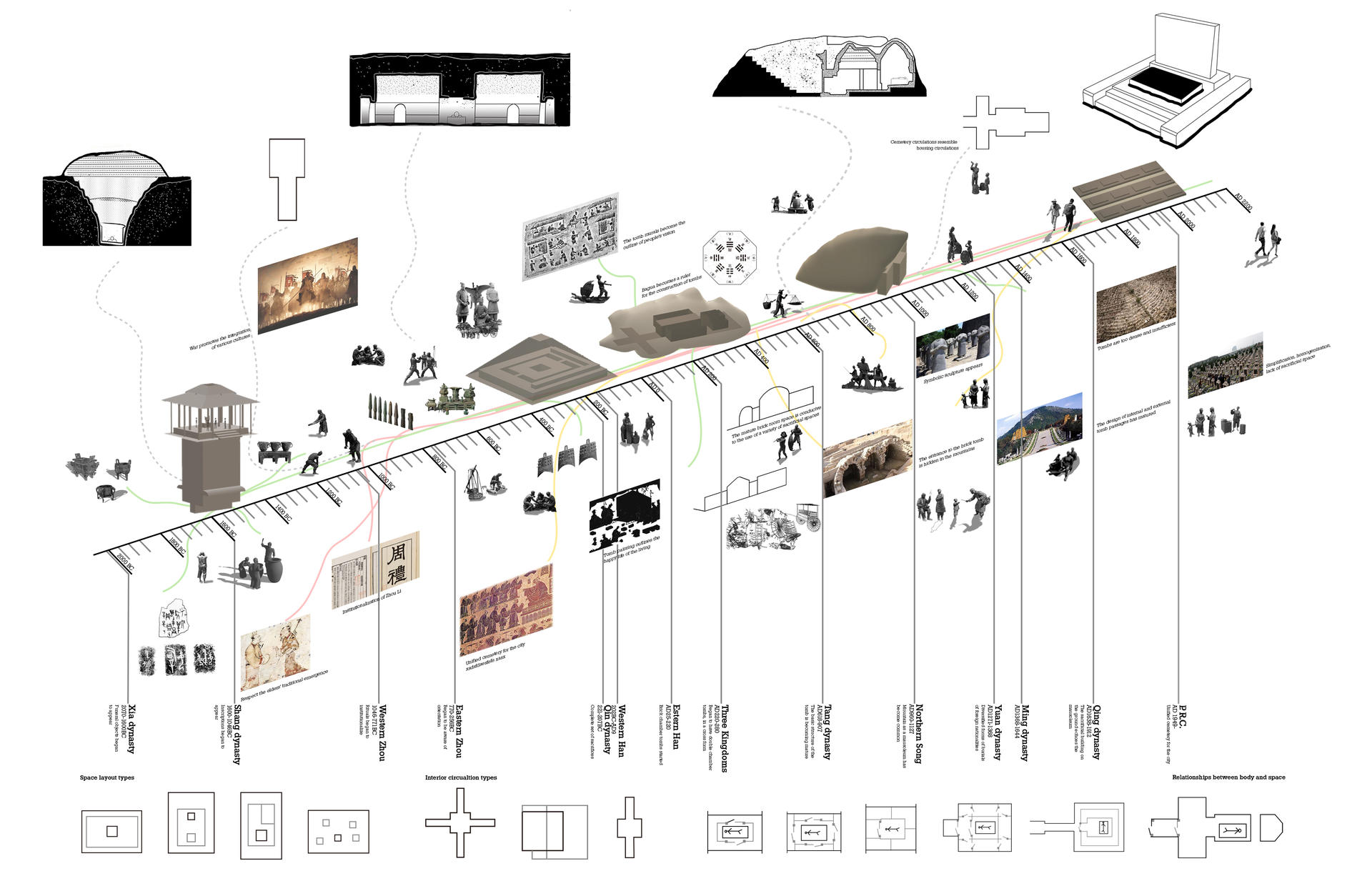

TIMELINE

Image

In my education, I have not yet encountered the subject of designing what I call “dead architecture”. So I want to take this opportunity by first analyzing and investigating the history and development of traditional Chinese funeral practices, and then by identifying the reasons for different tomb operations across the ages.

ANCIENT FUNERAL PRACTICES

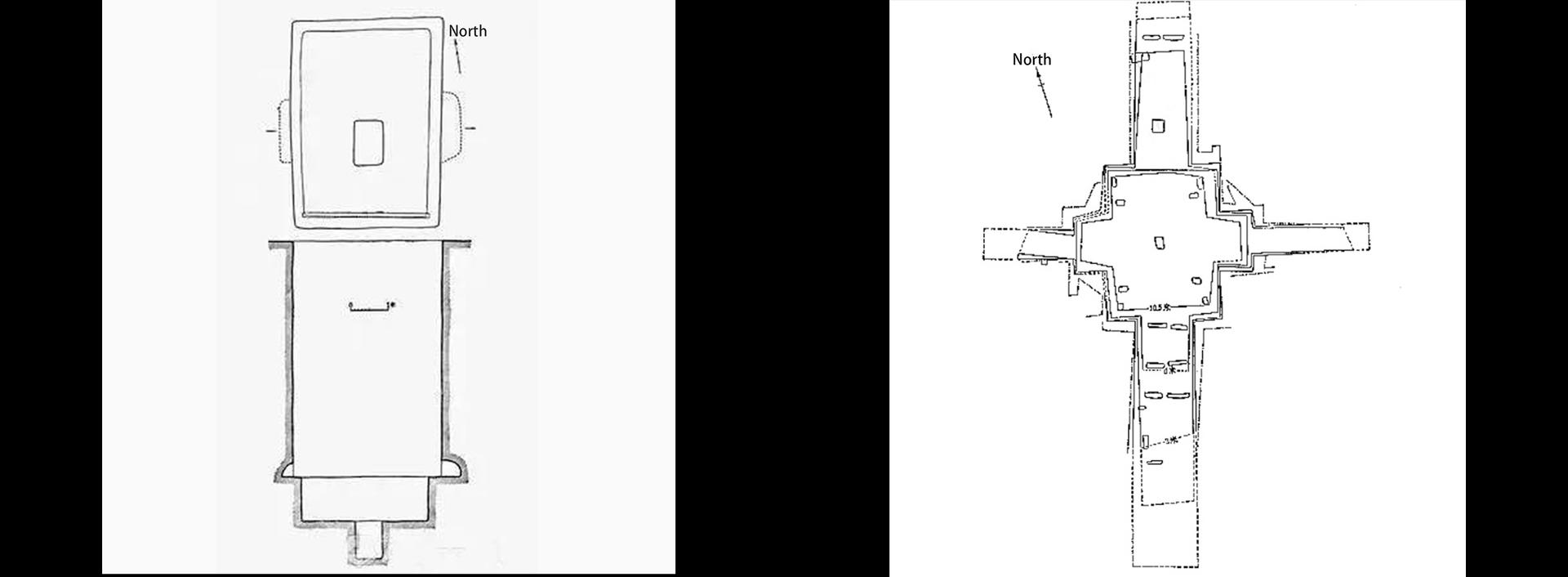

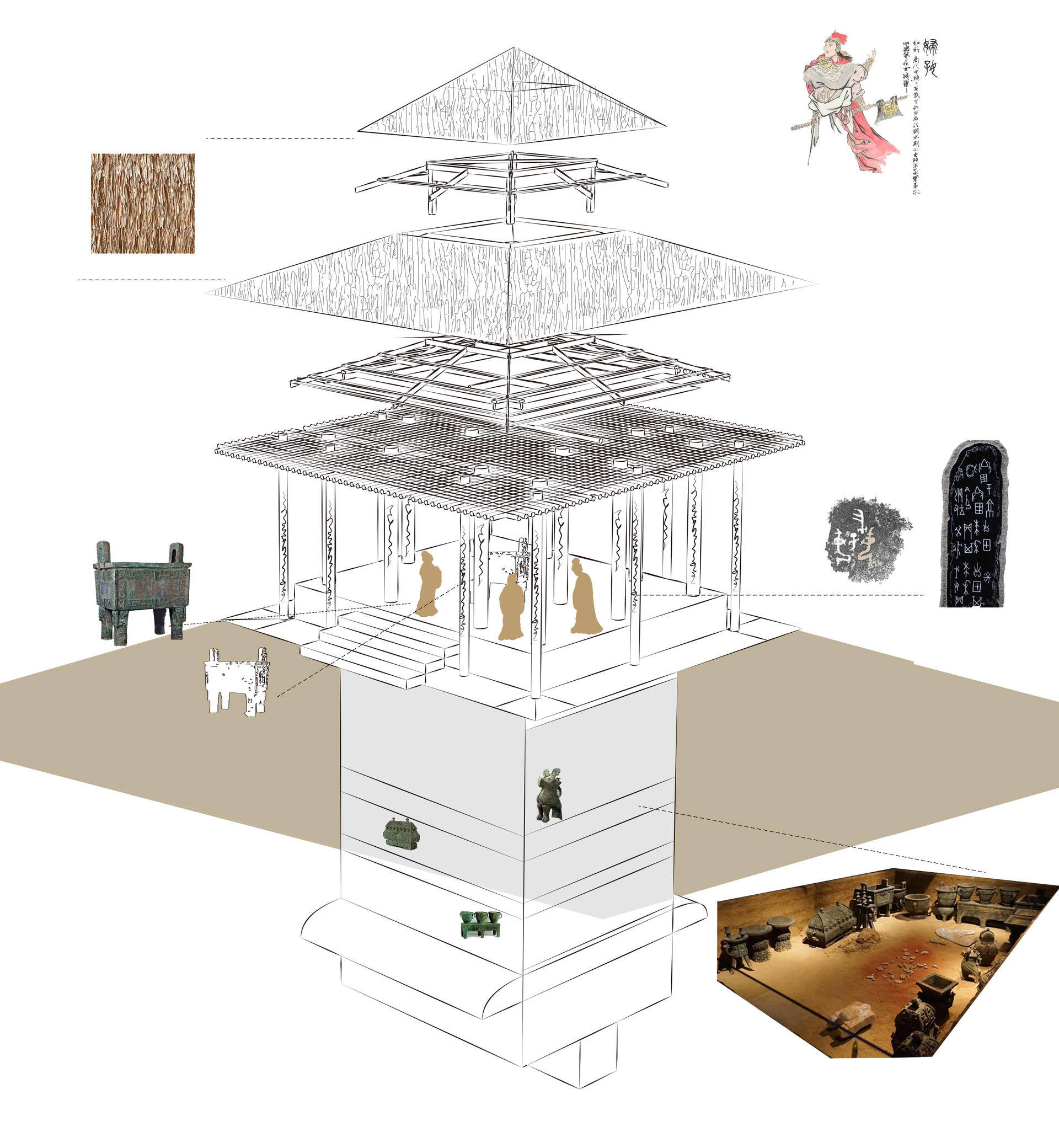

I selected a few ancient tombs that I think are representative of these practices, containing the basic configuration required by the chinese ancient tombs.

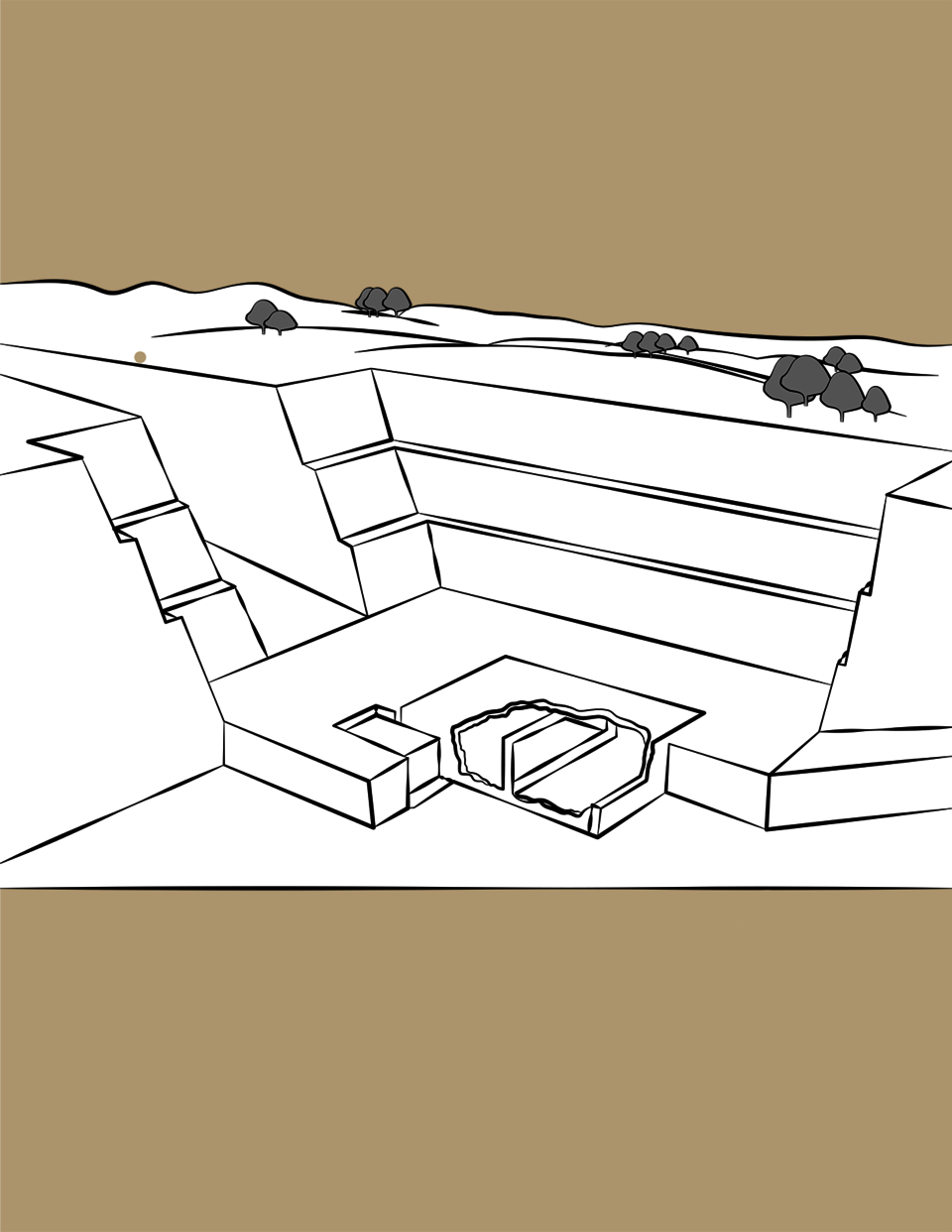

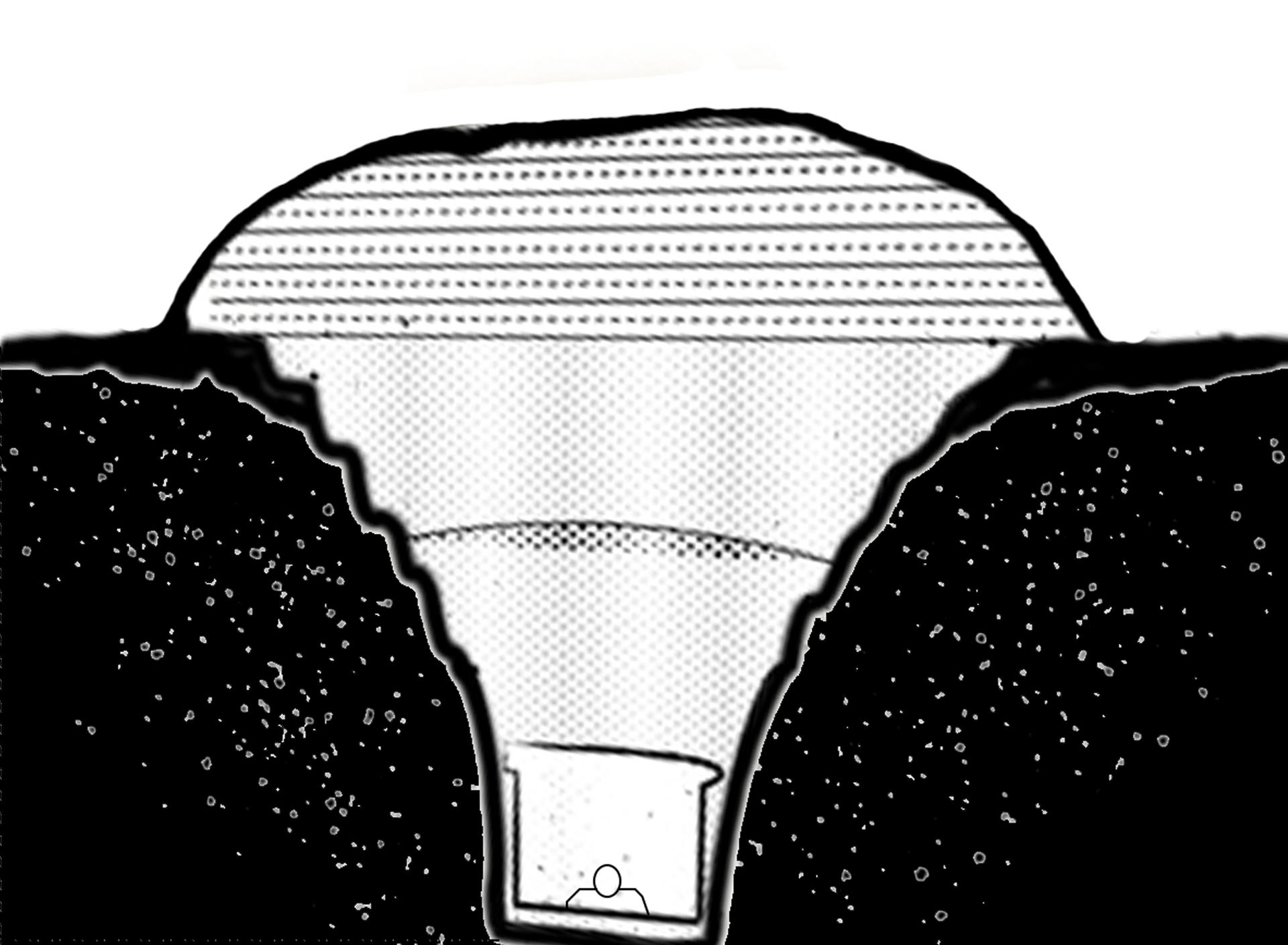

Deep Pit Tomb

Image

▲ Shang Dynasty - Qin Dynasty (1600 B.C. - 220 B.C.)

Image

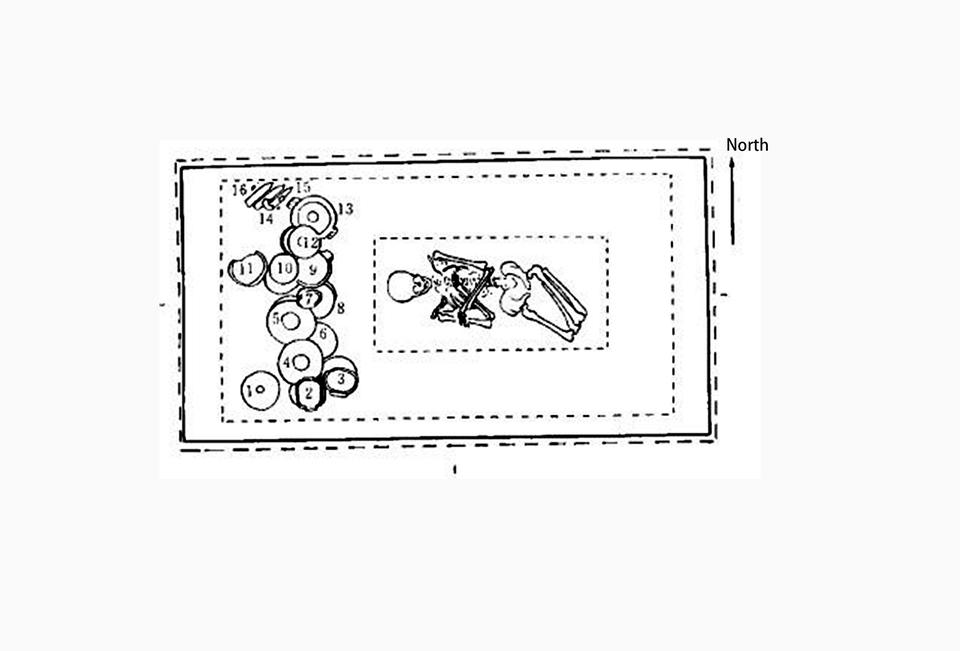

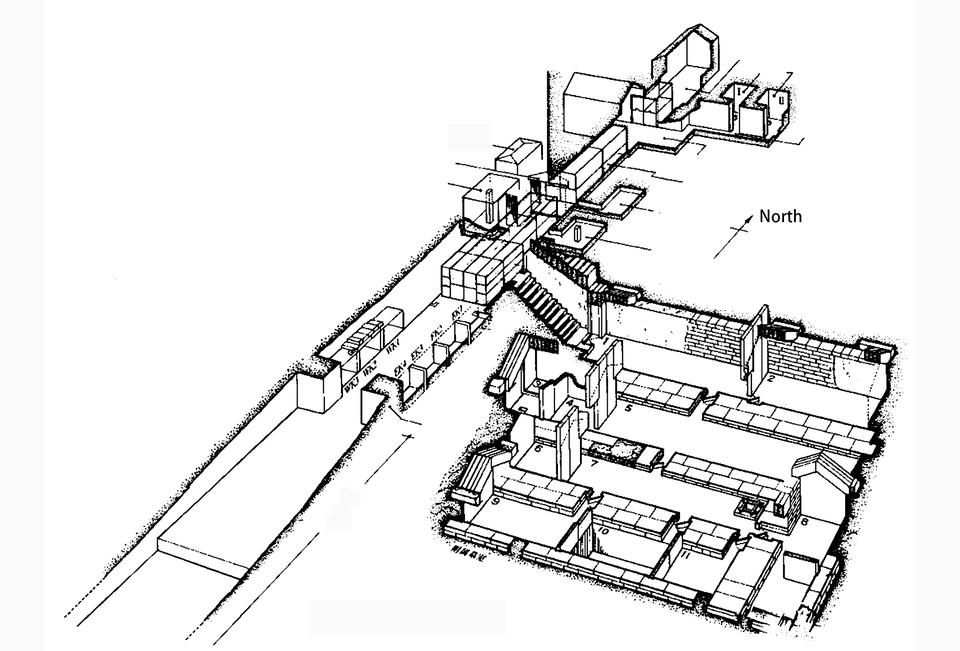

Fu Hao’s Tomb, Shang Dynasty, 1600- 1050 B.C.

Image

Plan(top) Section(down) Site circulation

Image

Image

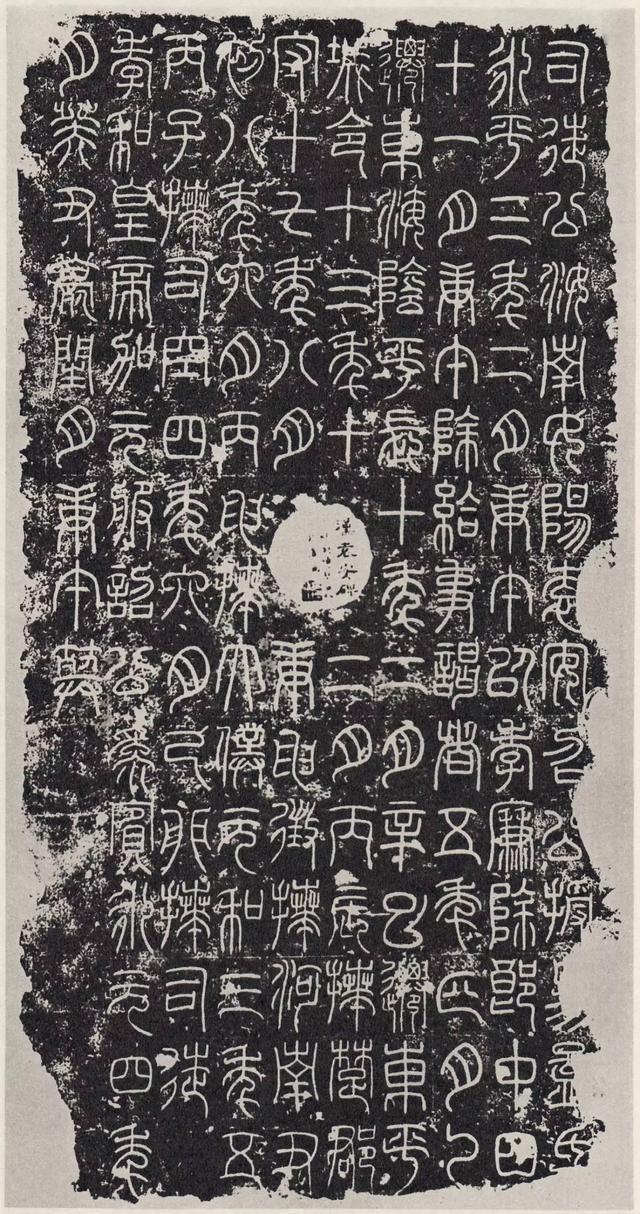

Inscriptions carved in tombstone

In Fuhao’s tomb from the Shang Dynasty, the first dynasty, people already designed the ceremony hall hidden the tomb architecture underneath, and people began to commemorate the dead with inscriptions that record the deceased's life experience, as well as the good wishes of future generations.

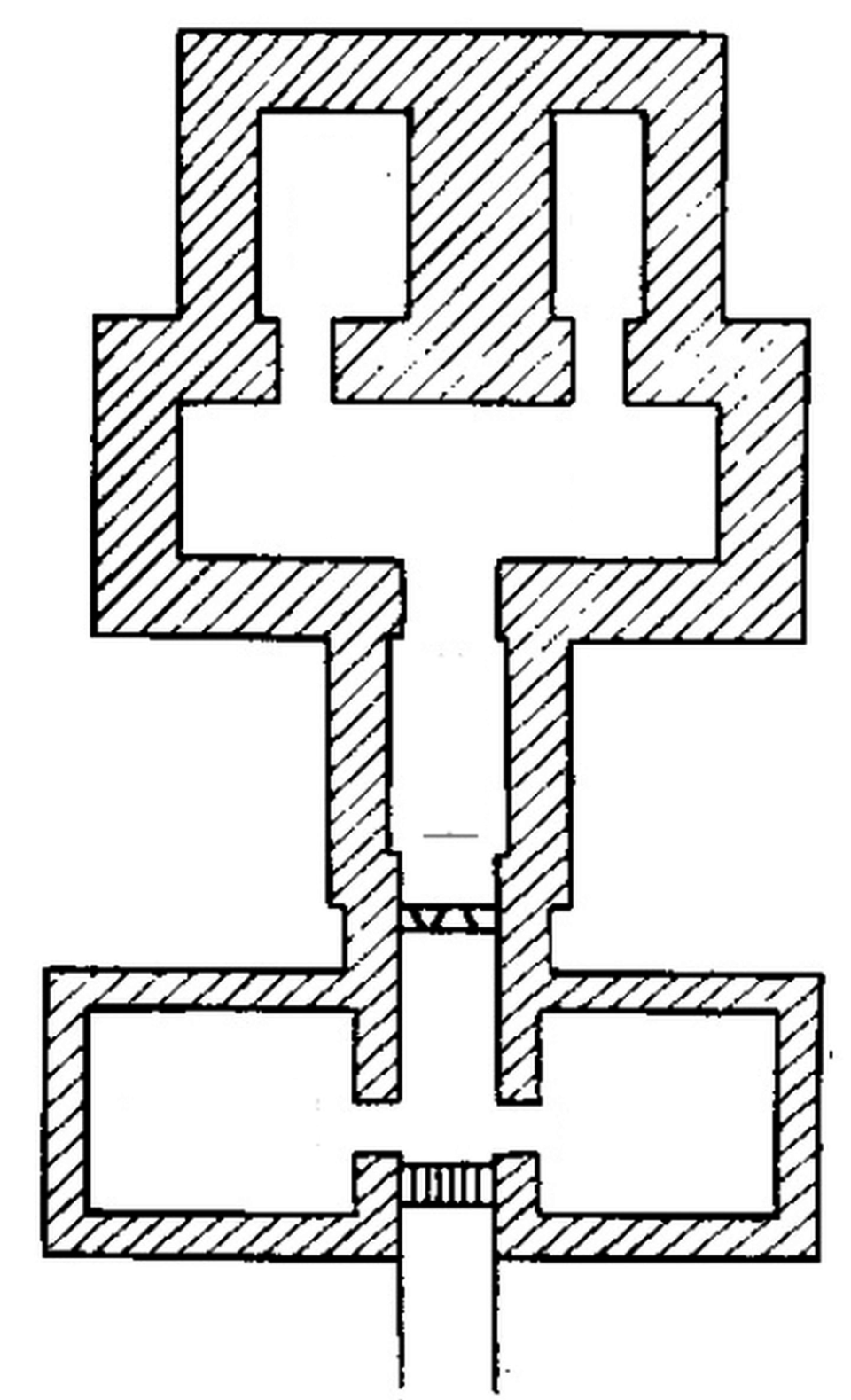

Palace Tomb

Image

▲ Qin Dynasty - West Han Dynasty (220 B.C. - 202 B.C.)

Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor, Qin Dynasty, 246- 208 B.C.

And in the Qin dynasty, people started to design multiple functions of the burial space in accordance with different rituals. The layout and arrangement of ancient tombs had a far-reaching impact on the imperial mausoleums of subsequent dynasties. Subterranean Palace tomb underground began to imitate the real palaces, imitating the death architecture of the emperor as his living space when he was alive. The funeral objects are also similar to those daily necessities, even creating Terra-cotta soldiers to protect the emperor.

Image

▲ West Han Emperor Tomb, West Han Dynasty, 202 - 8 B.C.

Image

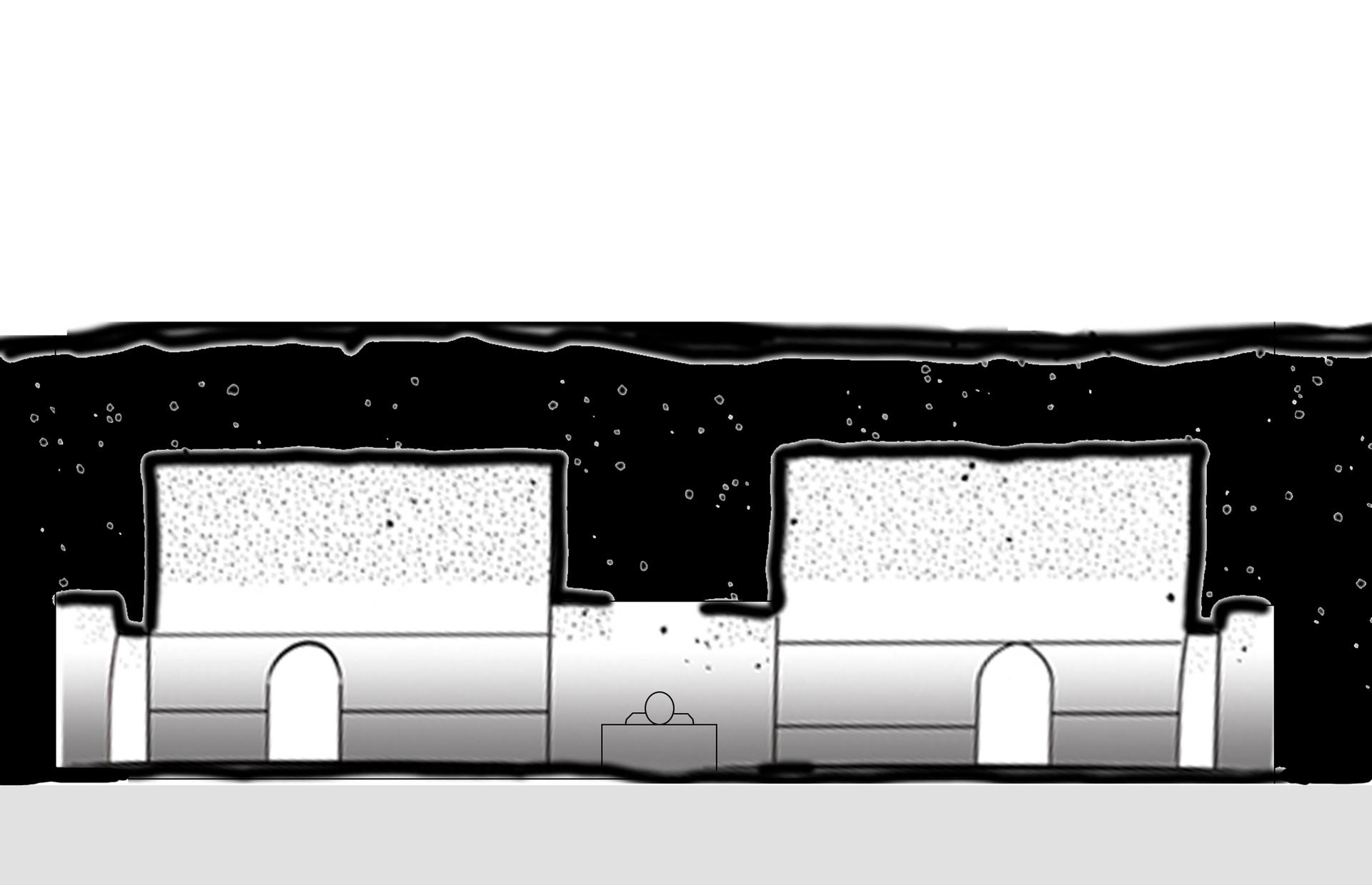

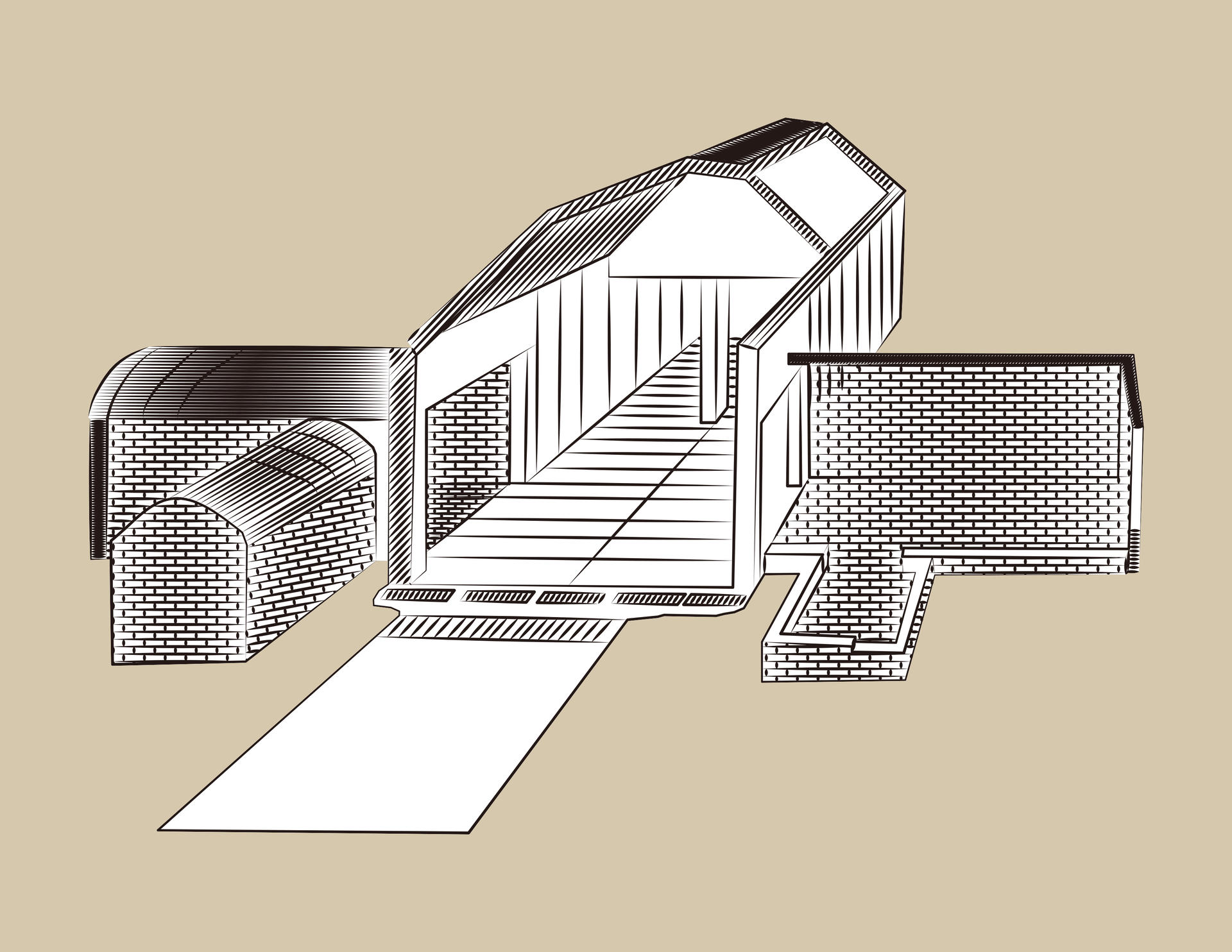

West Han Emperor Tomb, West Han Dynasty, 202 - 8 B.C.

In the funeral practices of the West Han Dynasty, the cemetery tended to imitate the living space -- as evident in the form and structures of buildings from this era. The underground tomb space replicates the housing space on the ground, because people believed that the tomb was the home of the deceased in the underground spiritual world.

Image

Zhao Mausoleum, Tang Dynasty, 589- 649 A.D.

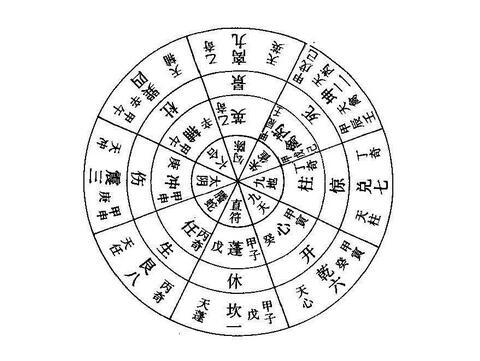

During the Tang Dynasty, the maturity of the rituals made the funeral ceremonies more and more systematic. Ritual theories such as Fengshui, Bagua helped people decide the location of tombs.

Image

Image

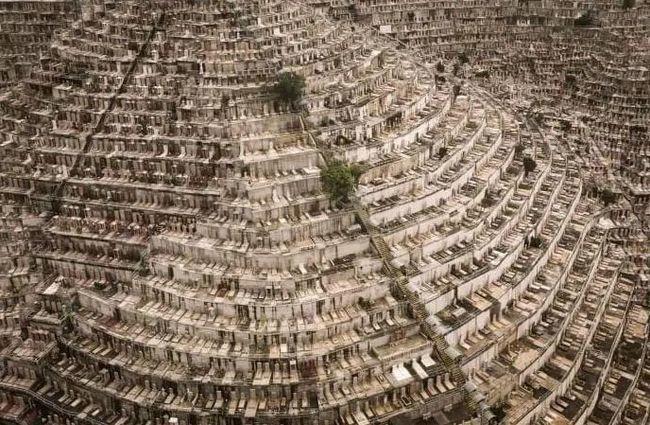

P.R.C 1949 -

Nowadays, due to the impact of social changes, foreign cultures, and government regulations, traditional funeral practices have been abandoned in cities and tombs have been converted to Western-style, public cemetery parks. However, many problems have arisen from this shift, including simplification and homogenization. Cremation does save burial space but lacks space for mourning, and as such, the private space left for people to memorialize the departed is tragically limited. The design does not take into account the core of the funeral practices: the rituals which, up until now, have been passed down over thousands of years.

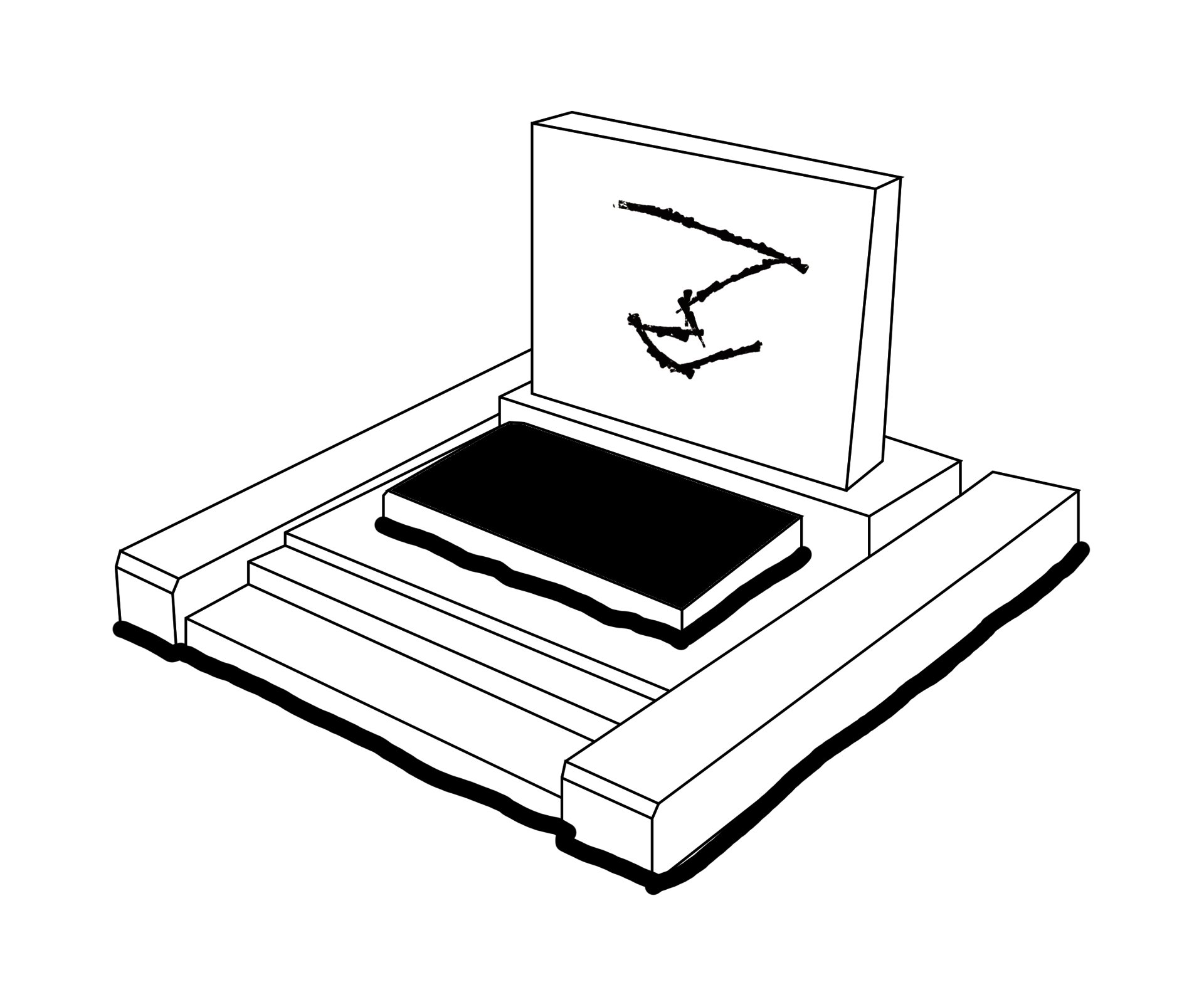

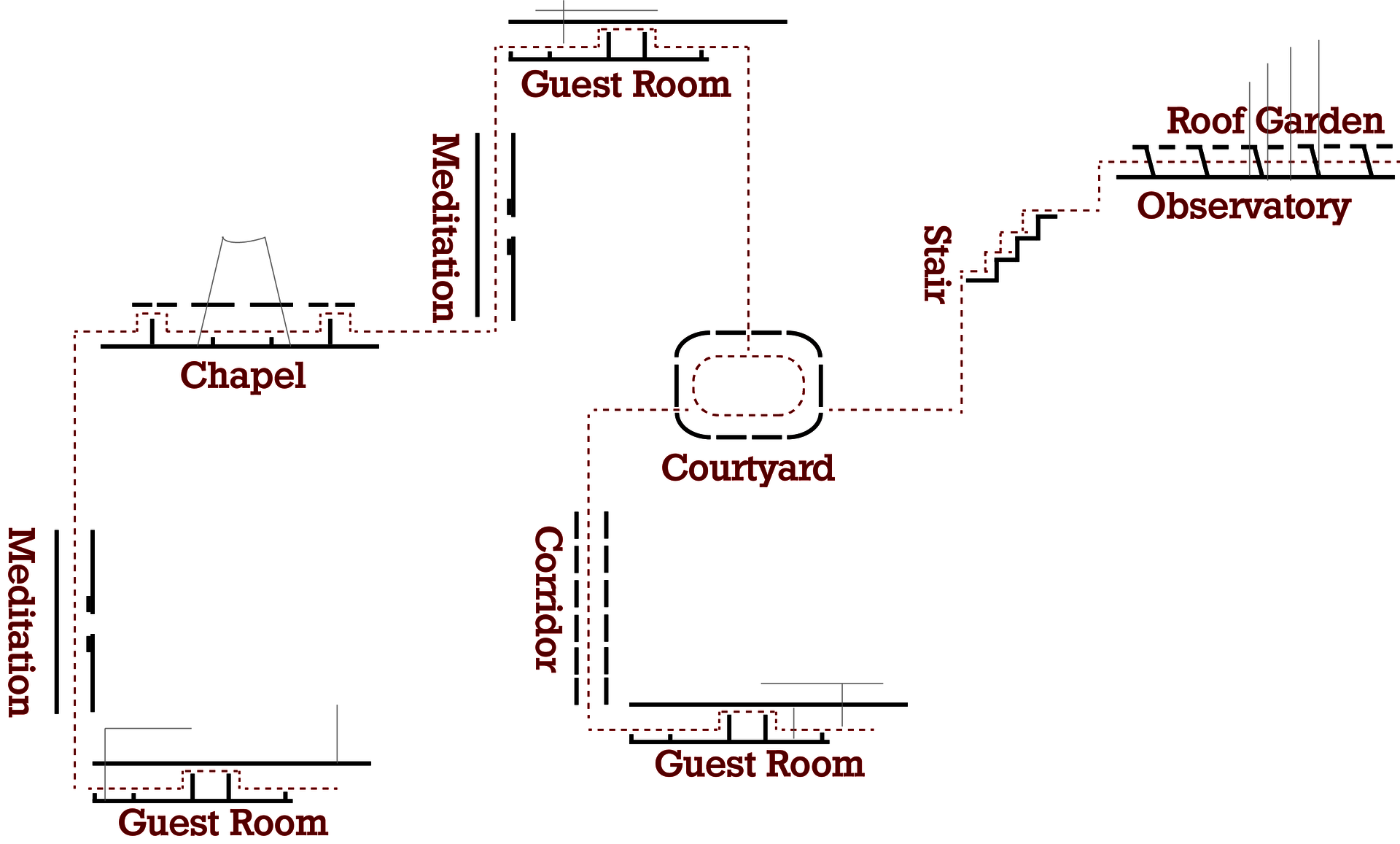

RITUALS

As a result, the core of my new cemetery mode design is about reconstructing the content of new rituals. According to traditional Chinese Confucian culture, The most important thing of ceremonies is to serve the dead as if they were living, as if they were still with us. In mourning, we should not go overboard, beyond fully expressing our grief. mourning is the most major part, is the process of living family members and friends resolving grief and accepting the death of relatives or friends. I break down the contents of mourning into six stages: sadness, calmness, farewell, sharing, healing, and memories. And I started an experiment to try and understand and conceptualize the corresponding architectural answers in turn. Saying goodbye to the deceased body in the private space of the chapel, keeping calm in the soft light and shadow space, sharing the sadness with relatives or friends in the public courtyard, after walking up to the garden, healing in the natural environment of the observation deck, and finally embracing and accepting the death, where the body is returned to nature, and the passing of the individual gives birth to a new life, where new memories may bloom.

SADNESS - CALMNESS - FAREWELL - SHARING - HEALING - MEMORIES

Image

SITE

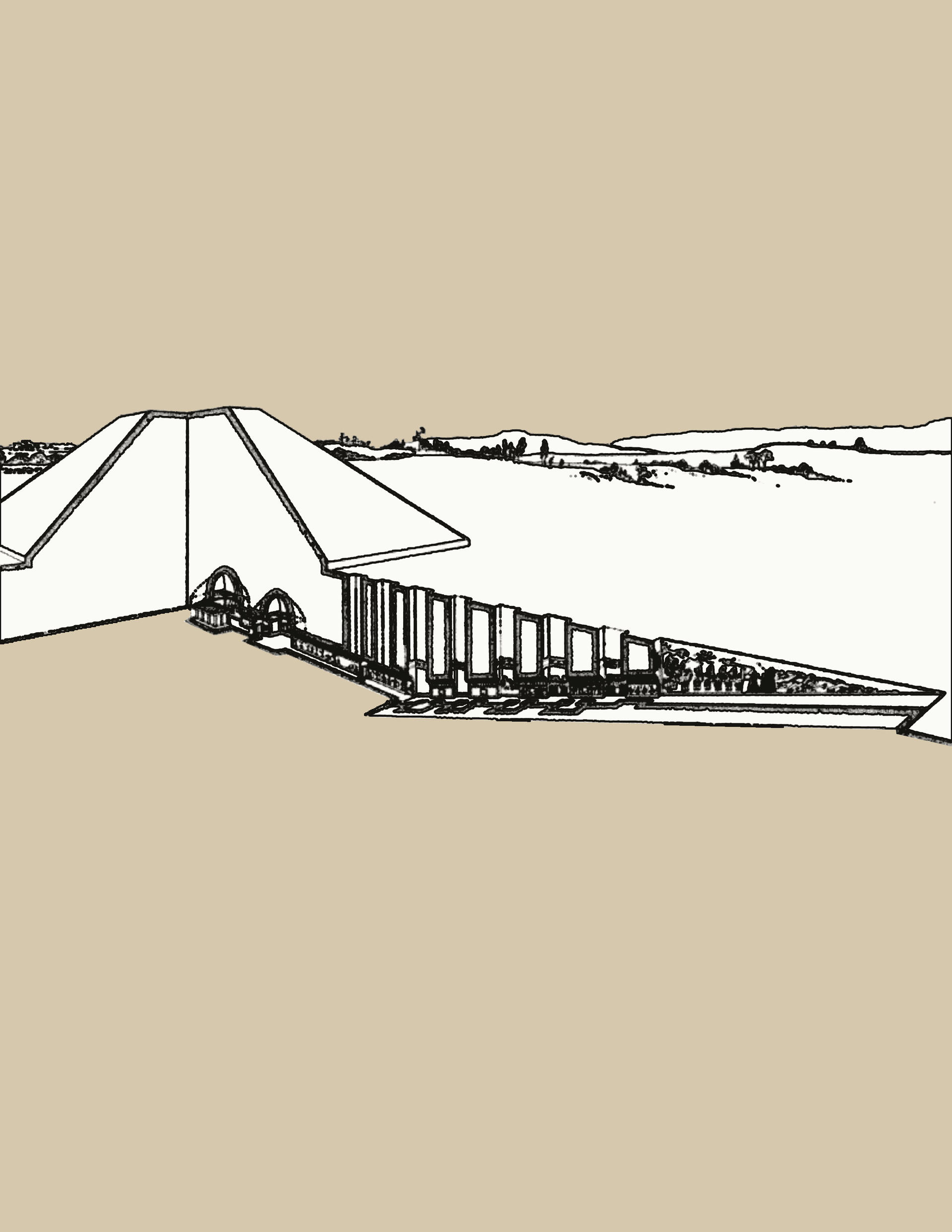

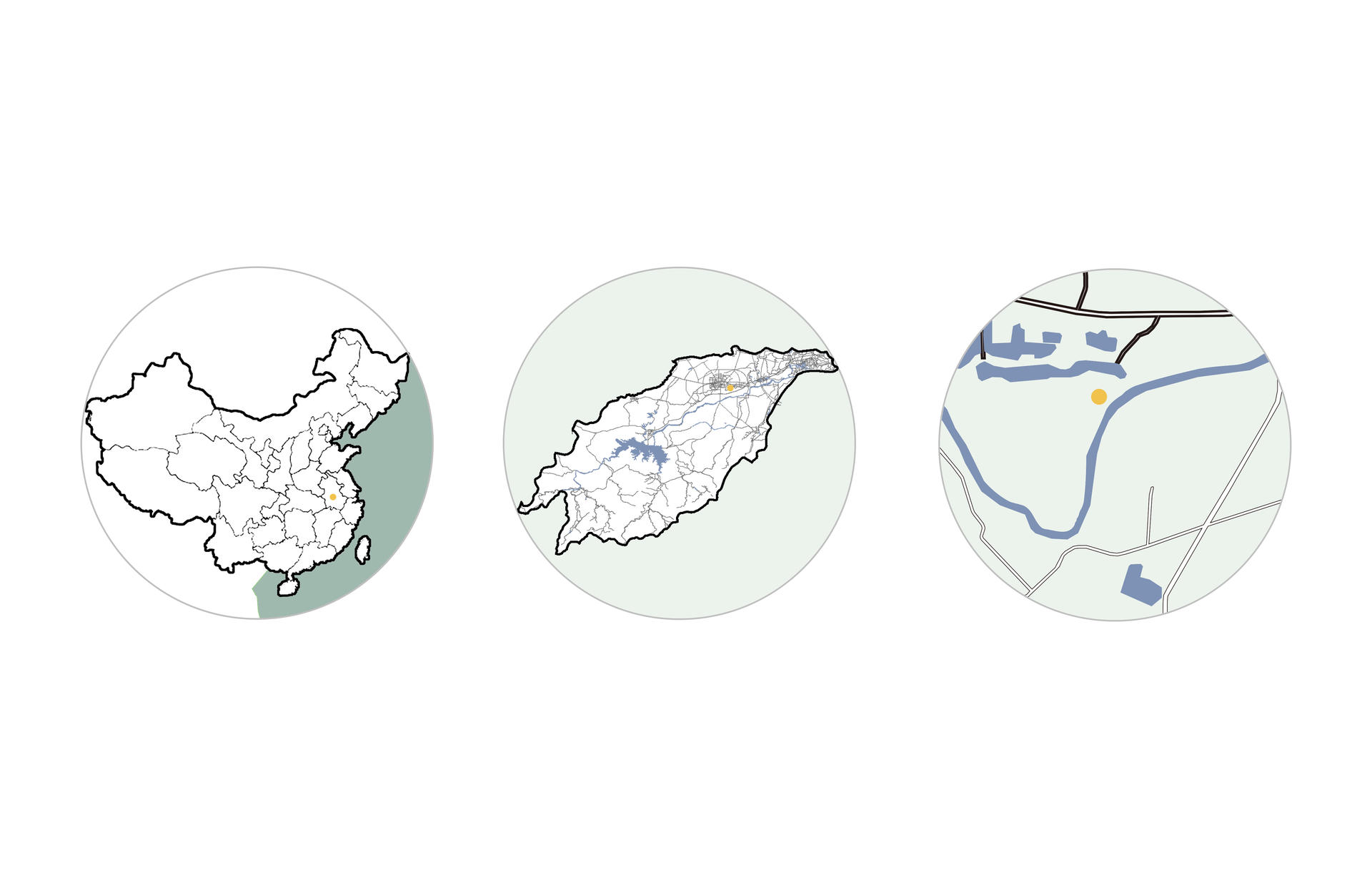

Here is the site called Shucheng, which is a county in the west-central part of Anhui Province. The area is famous for tea, and its architecture is also very distinctive. Huizhou Architecture is one of the traditional Chinese architecture styles. The architecture uses bricks, wood, and stone as raw materials, notably timber frames as significant structures. Huizhou Architecture is rich in bamboo and bamboo crafts as well.

Image

Image

Image

Image

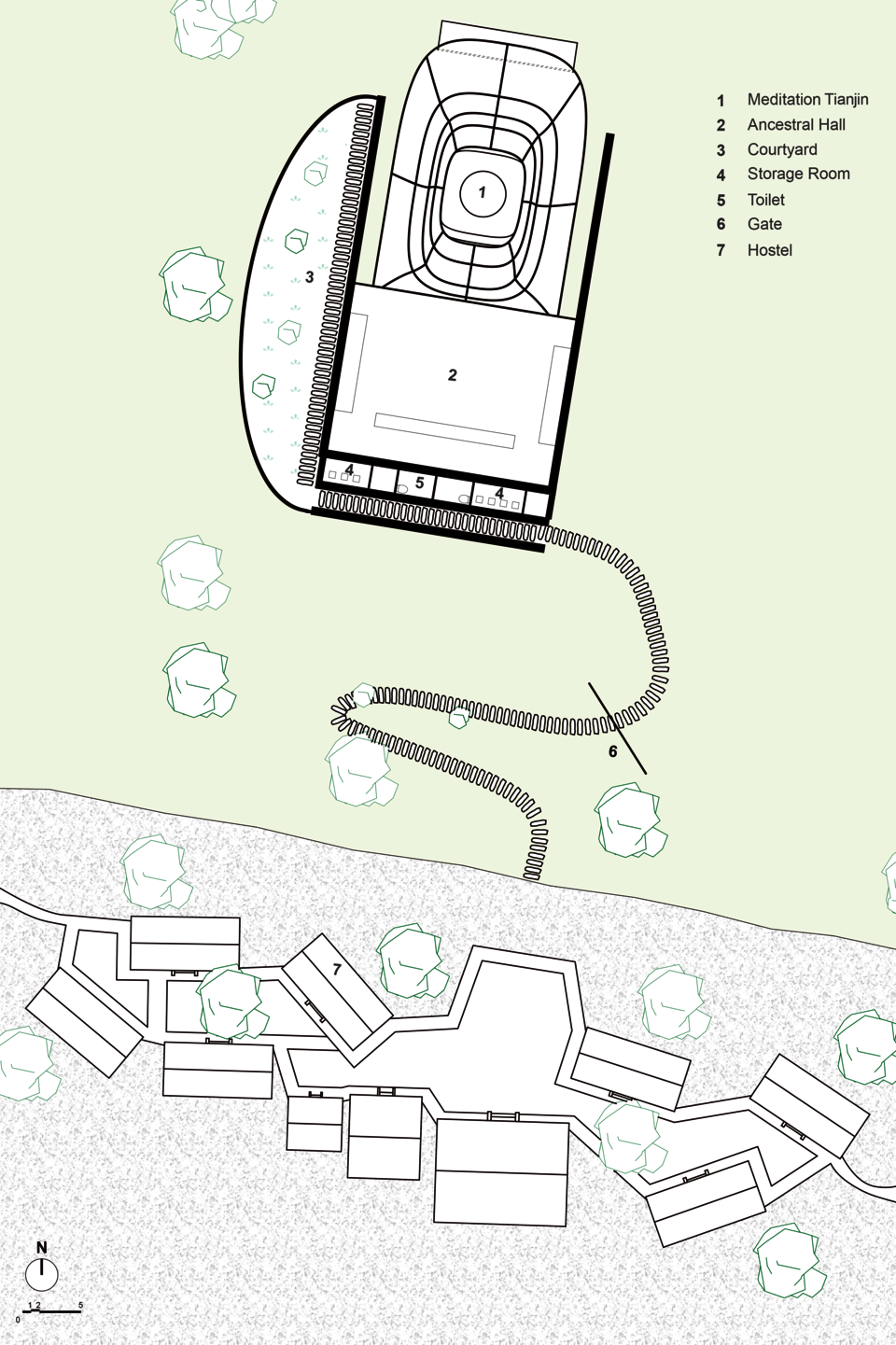

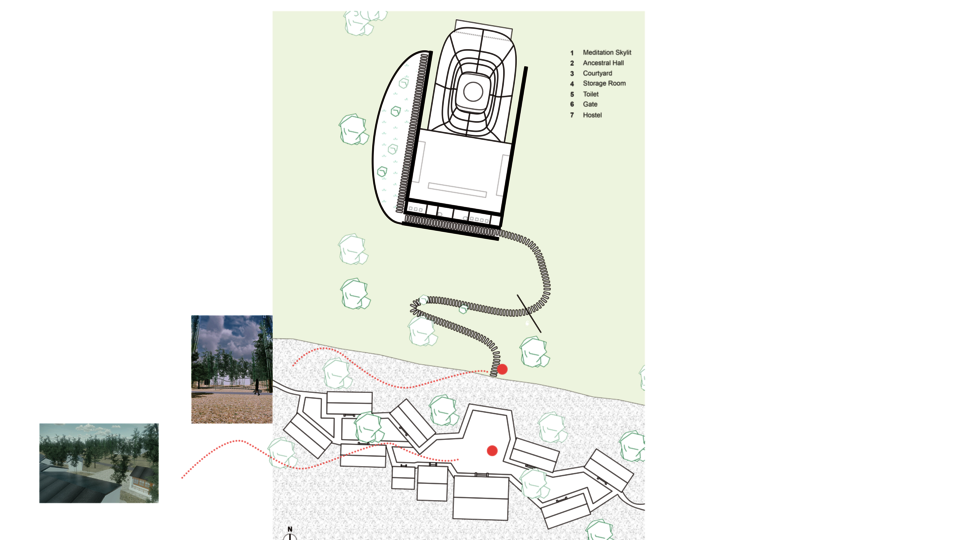

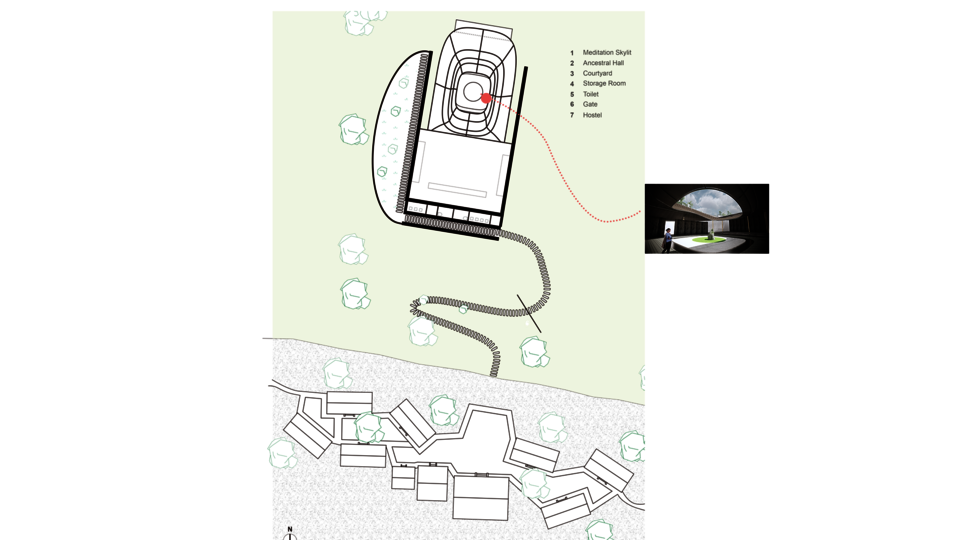

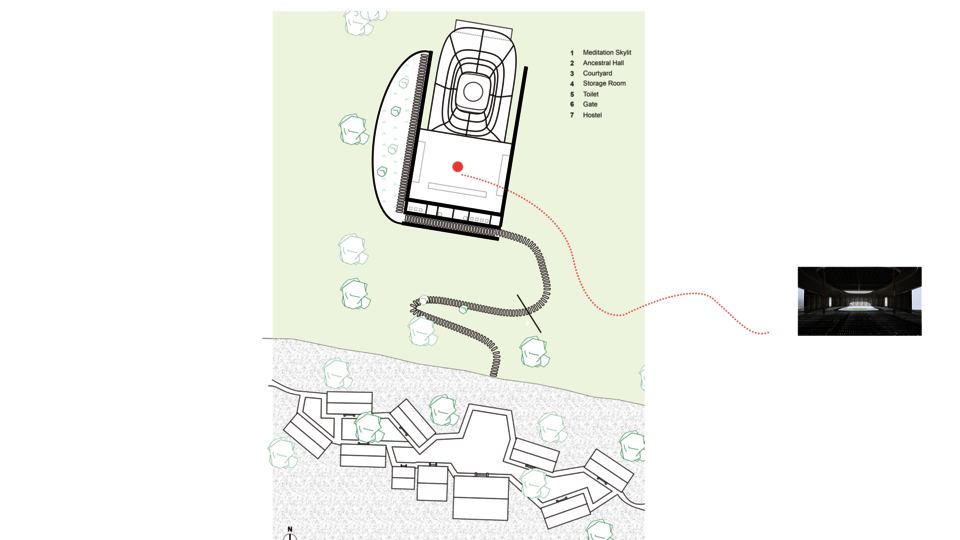

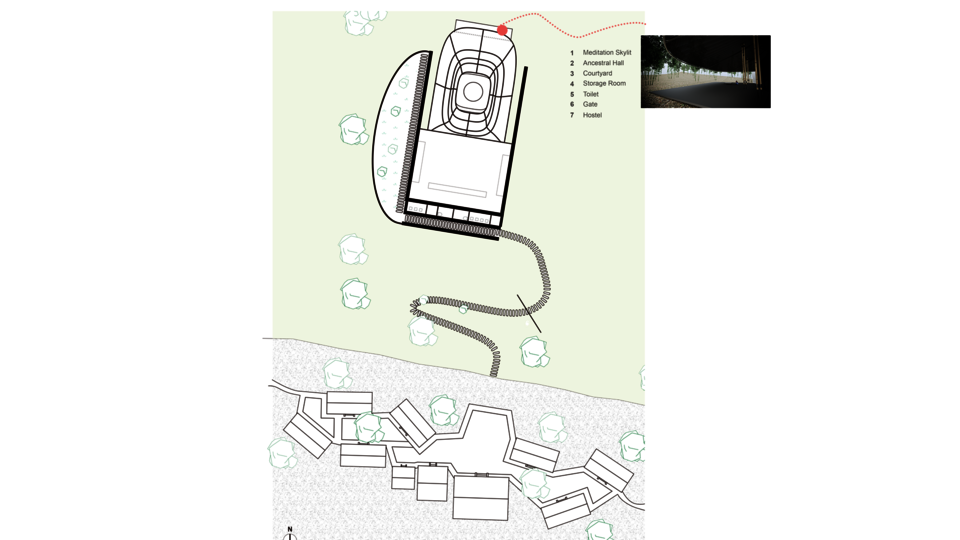

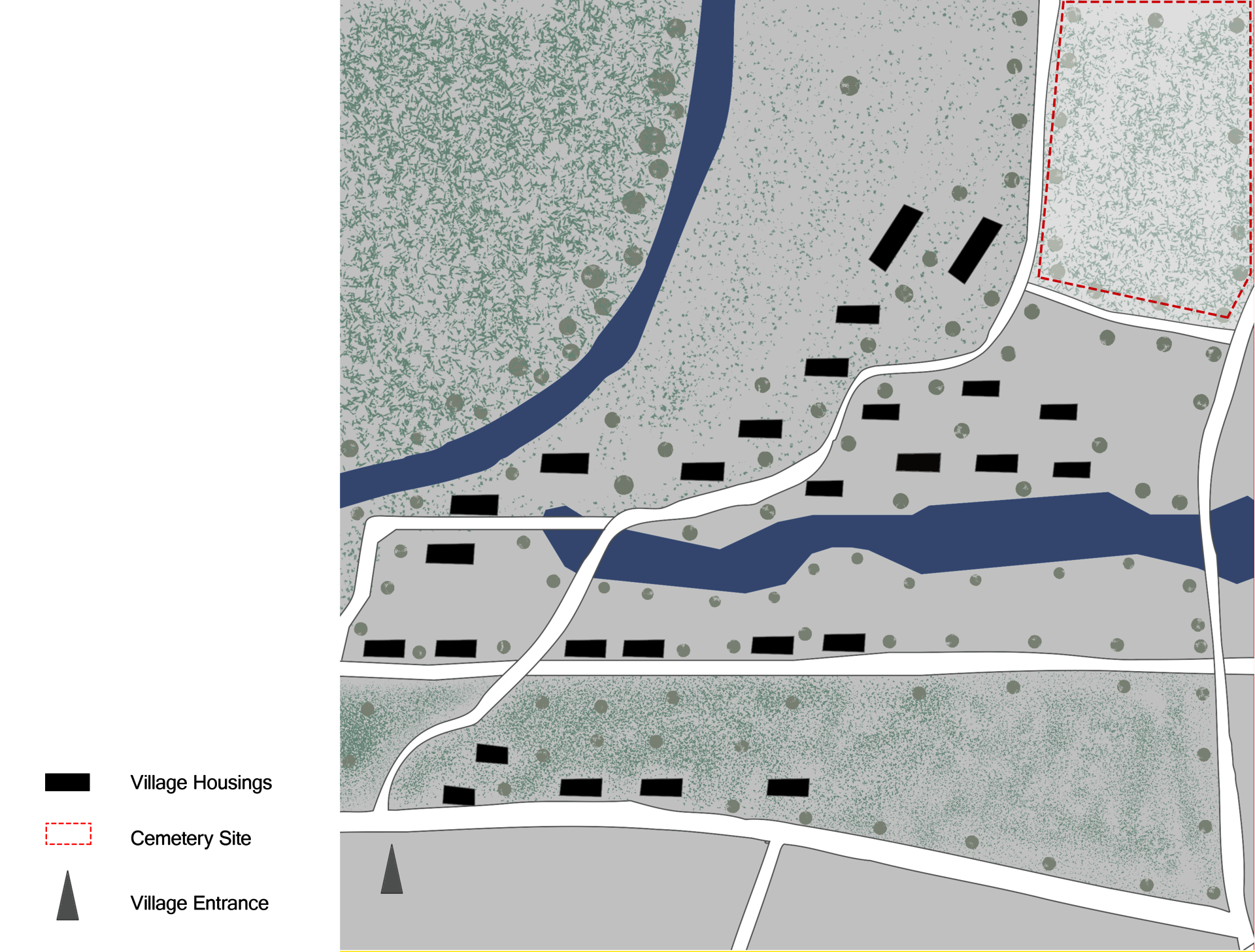

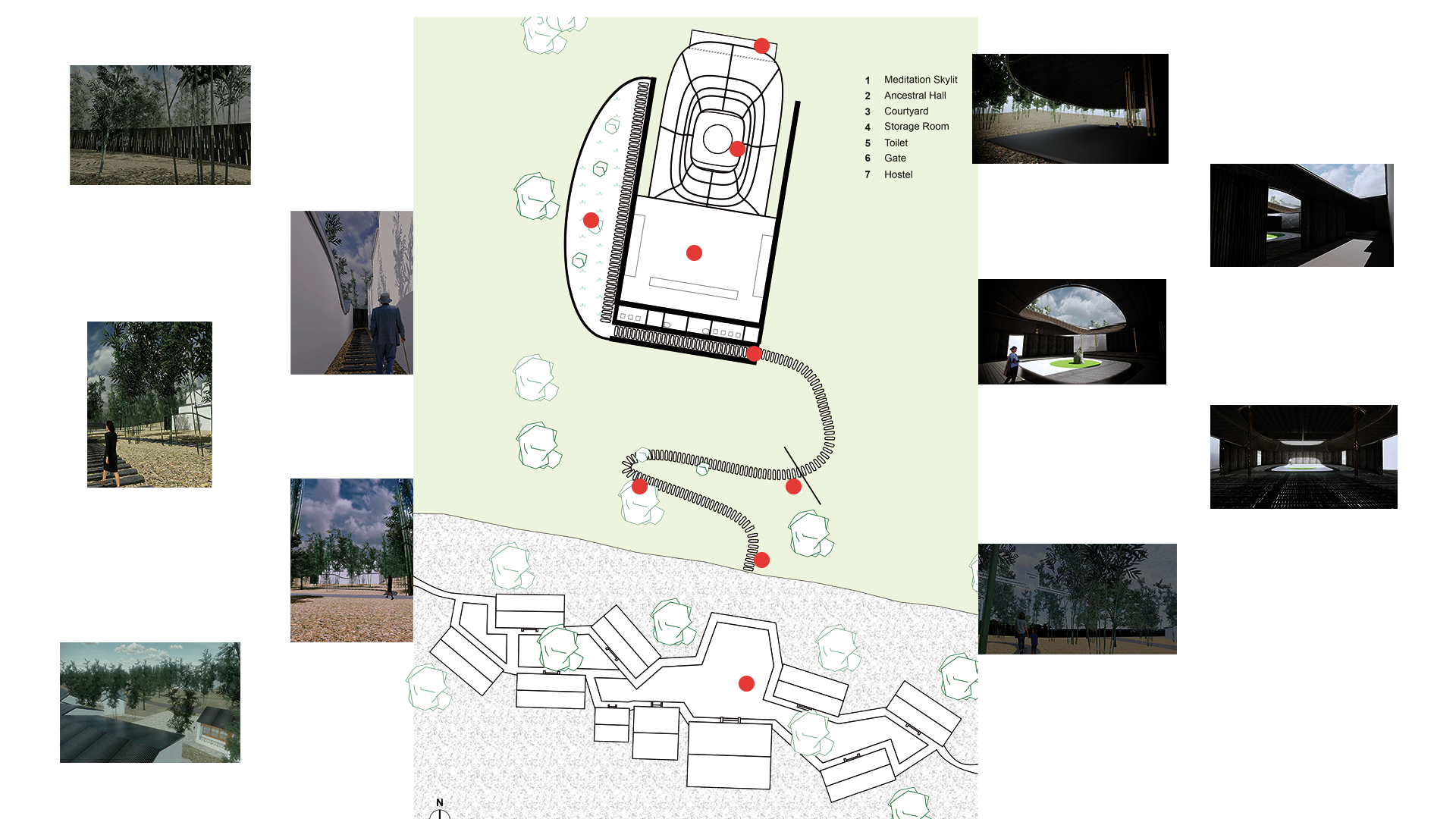

Here is the site map. The black blocks represent temporary dwellings for attending mourners, the gray arrow represents the entrance to the village, the red area for the cemetery, which is in a bamboo forest, at the end of the village. A very important piece of background information on this village is that there was a couple who migrated here to raise their family because of the Sino-Japanese war, where all village members had a blood relationship, which is why I consider design as a bigger space for the whole village, not just my grandfather. The deceased from this village can have their tombstone or memorial ancestral tablet in the ceremony hall. This idea also offers an opportunity: if someone is unable to return to the village to mourn for whatever reason, others who are able to be there can express grief and mourn on their behalf of them. Most of the new generation will not reside there permanently, hence the temporary housing in the village for short stays and the abundance of hostels for visitors and family to rent.

Image

Image

Image

As I mentioned before. Bamboo elements are embedded in the roofs and walls in the local residents’ houses.

I found one material that I’d apply to that site called bamboo reinforced concrete. It has a raw, natural, and non-decorative material language. The main building structure is constructed of concrete with a bamboo framework. The bamboo texture left on the concrete surface reduces the visual and material scale of the concrete wall and harmonizes with the surrounding trees and greenery.

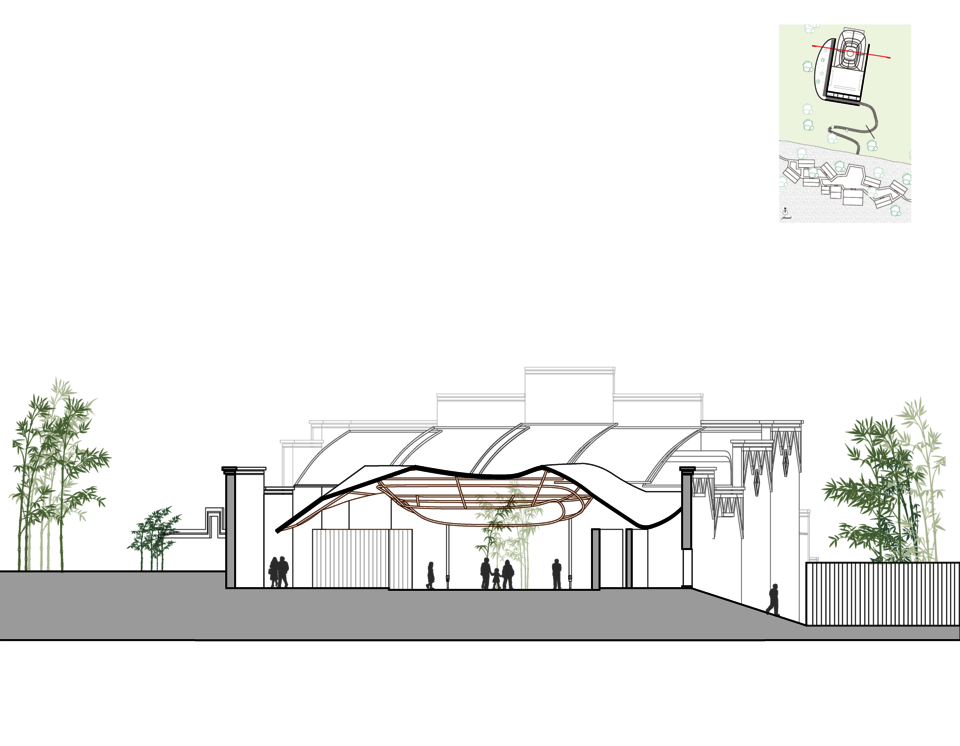

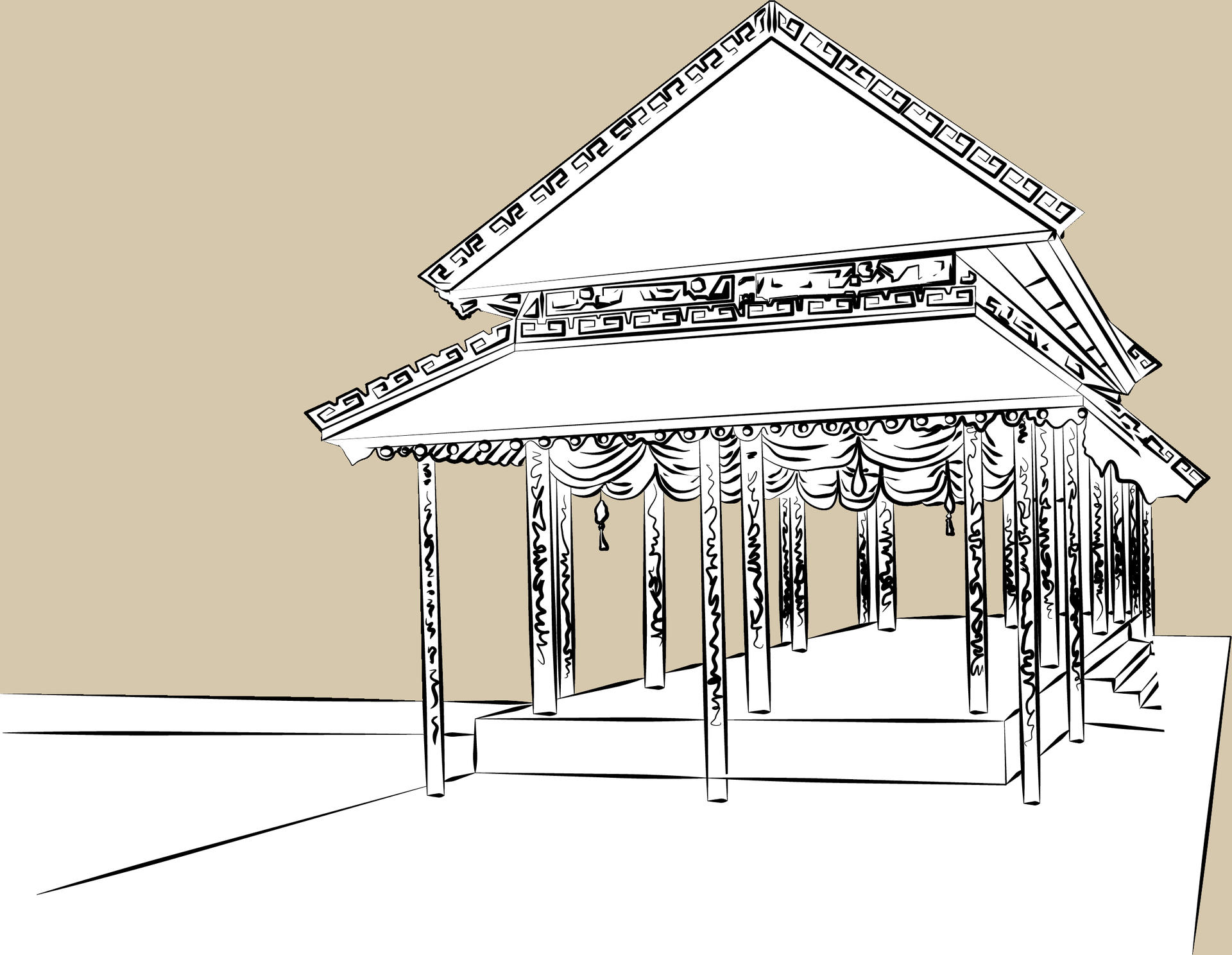

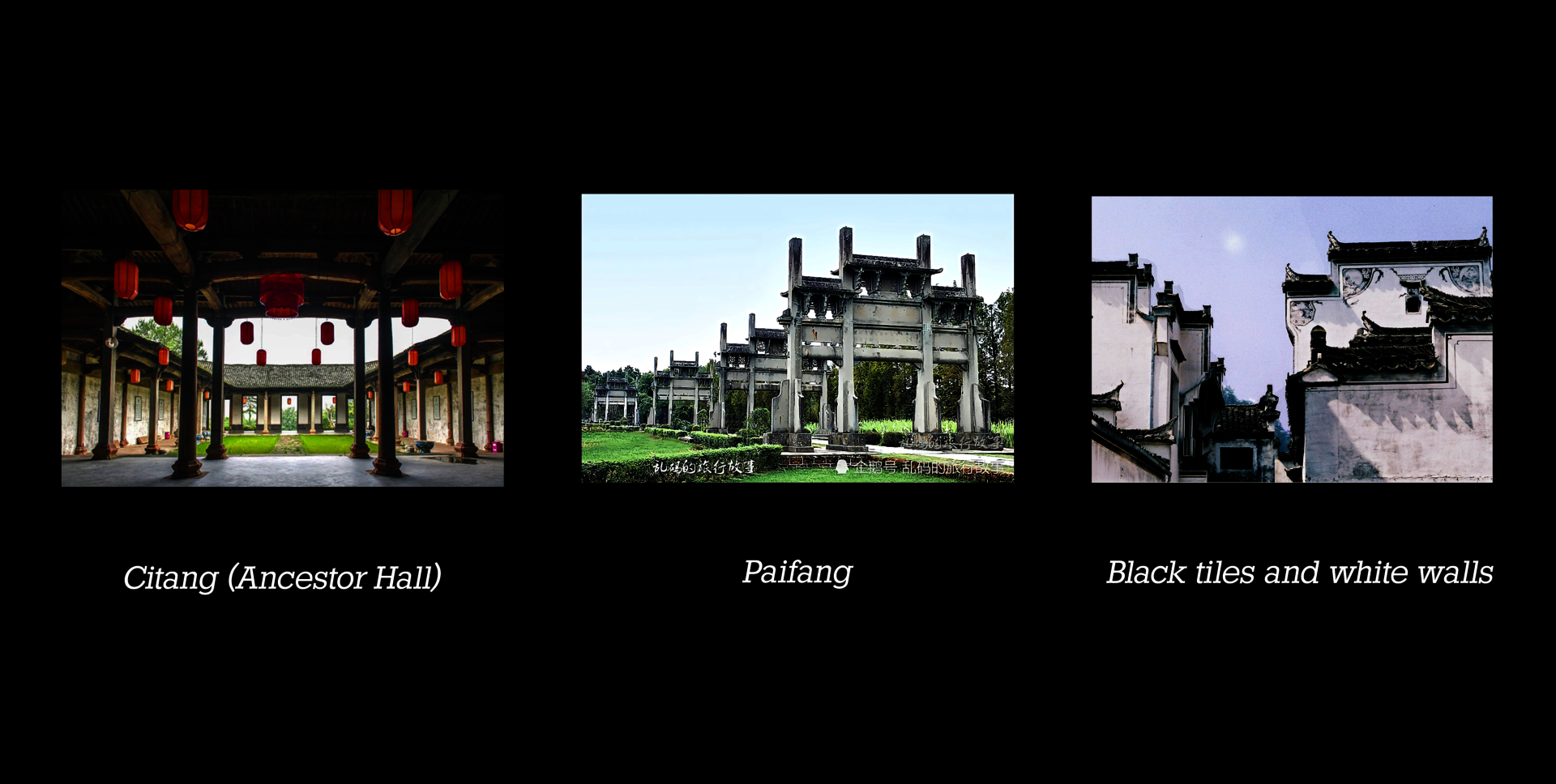

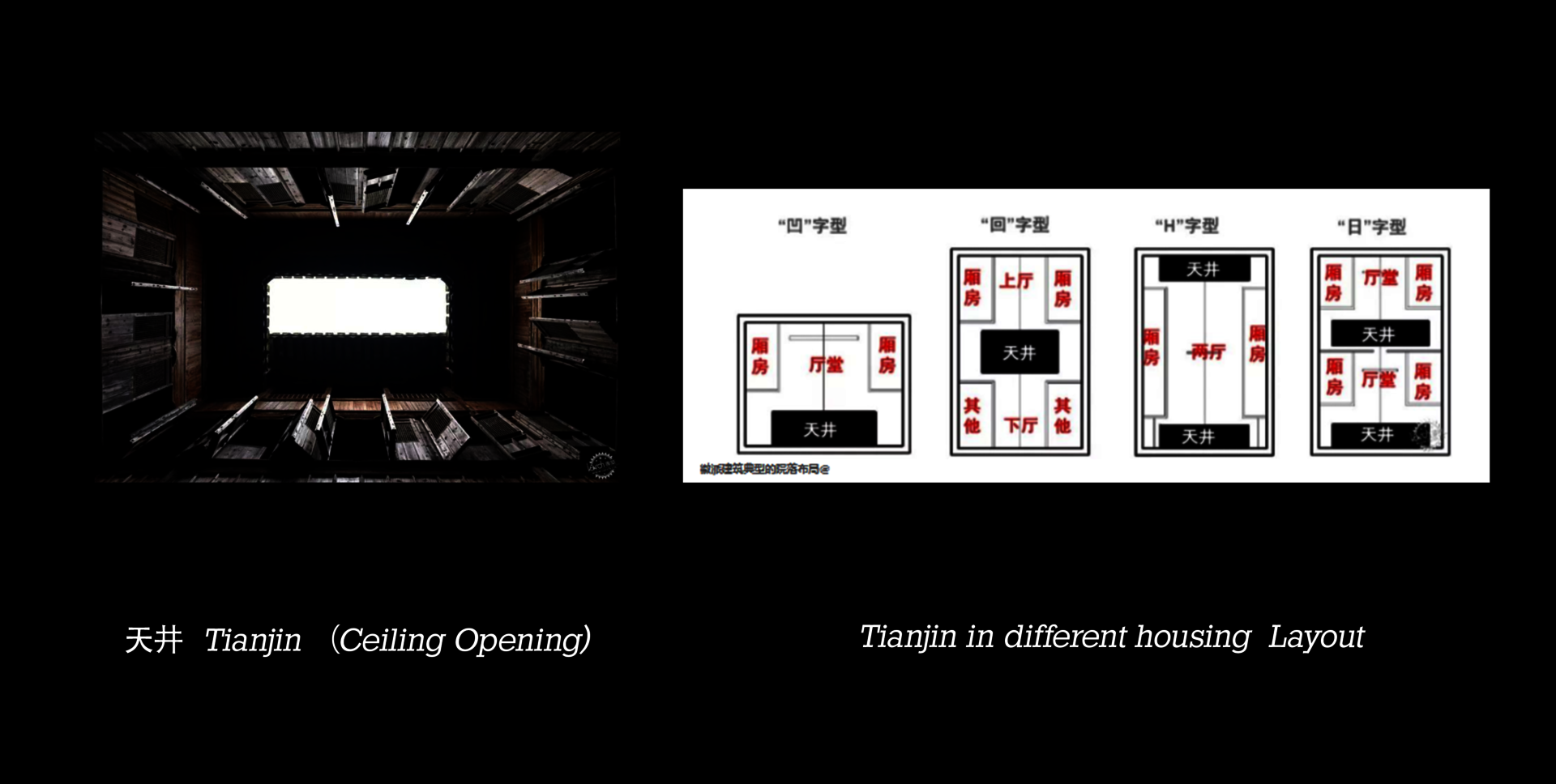

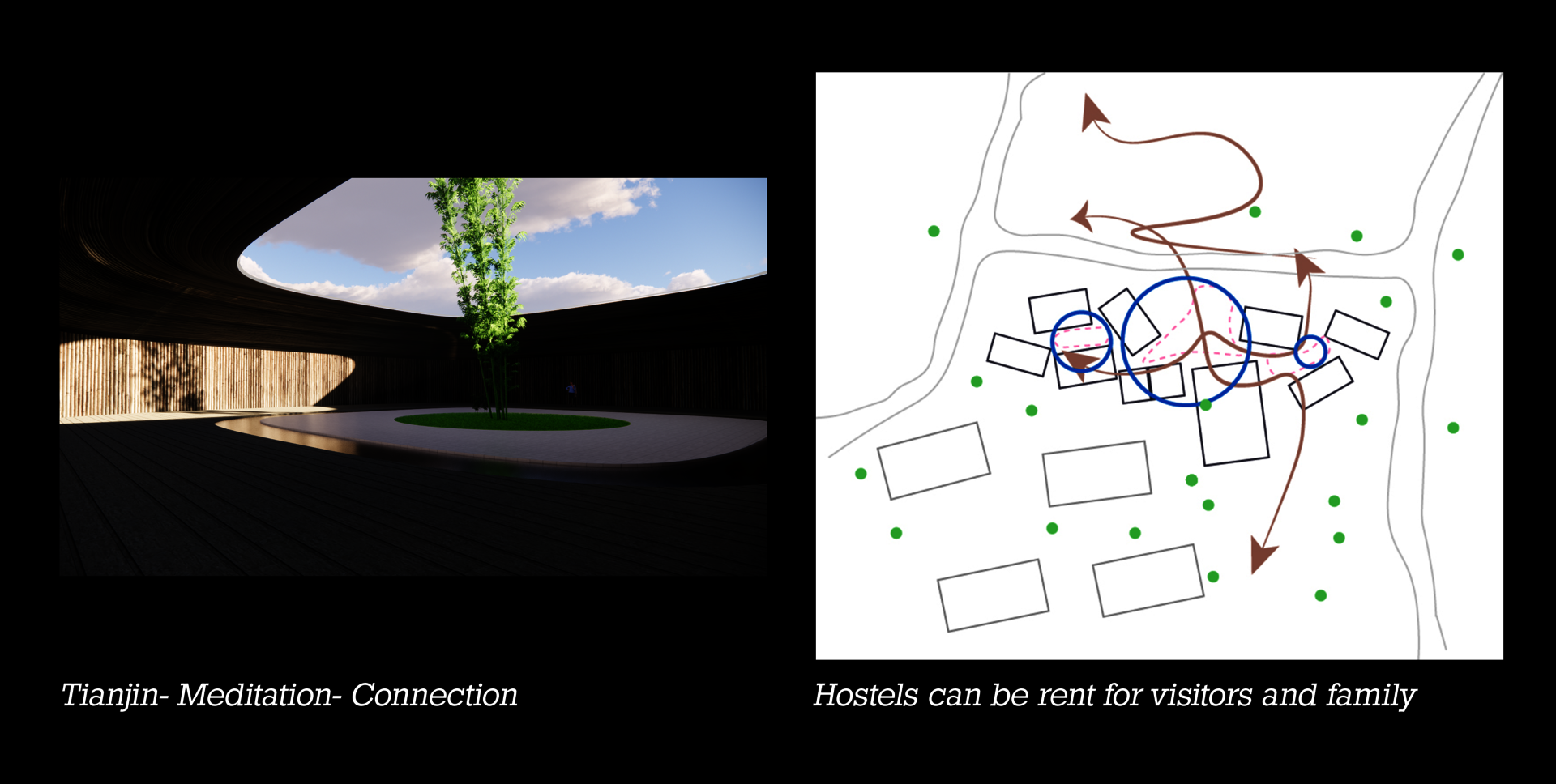

I also researched some unique local architectural language, which would be used in the funeral practice environment, citang also can be called: the ancestral hall and it is the space for local funeral ceremonies, paifang is the traditional style of Chinese architectural arch or a gateway structure. This can be translated as a cemetery entrance. The building style would imitate the local residential buildings, which feature black tiles and white walls. In terms of spatial structure, tianjin (a Chinese word that translates to “ceiling opening”) is widely used in local housing. These ceiling openings often served as bridge connections between different spaces and possessed meditative qualities in the simplicity of their design and in their inherent opening to the natural world.

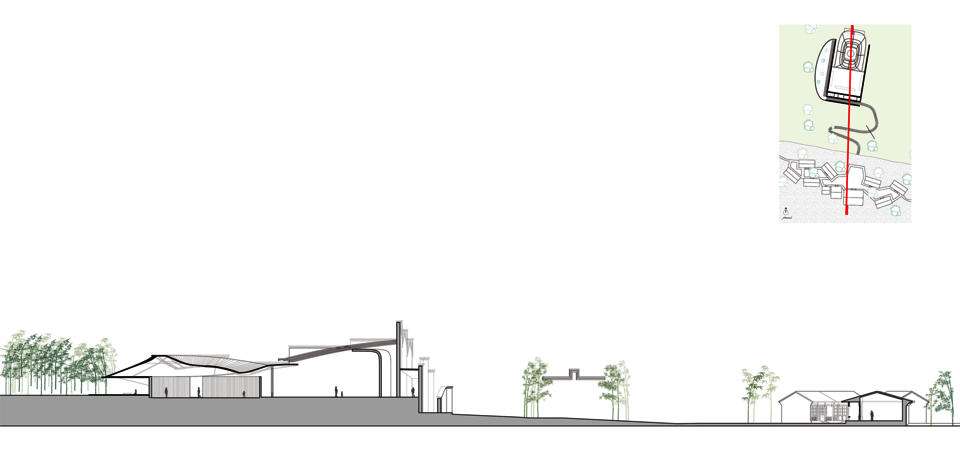

The placement of the temporary housing could also convey tianjin layout methods. A few hostels surround with a blue circle open public space for people doing activities, The design of the path should be winding and winding along with the bamboo forest, so that the whole building can be hidden by nature visually, and people living in the hostels can’t see the hall directly.

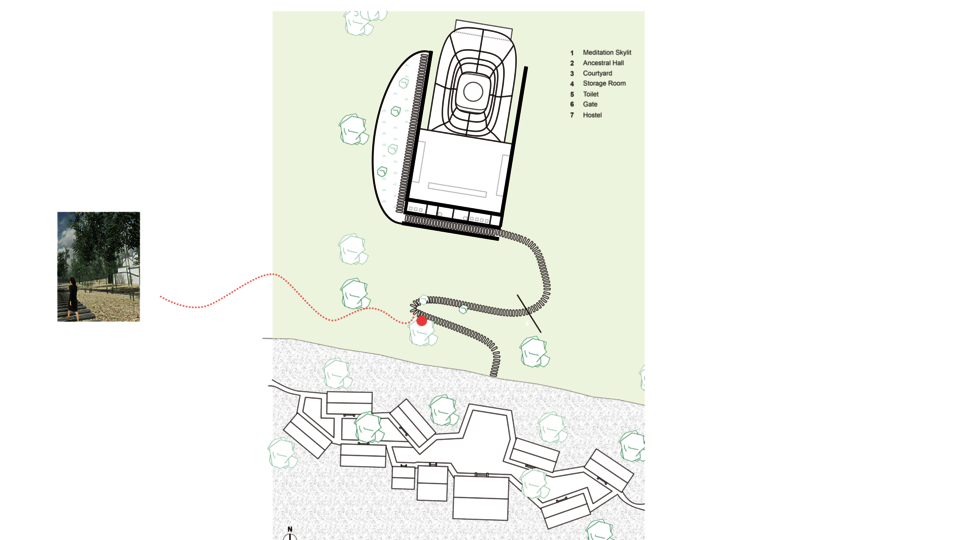

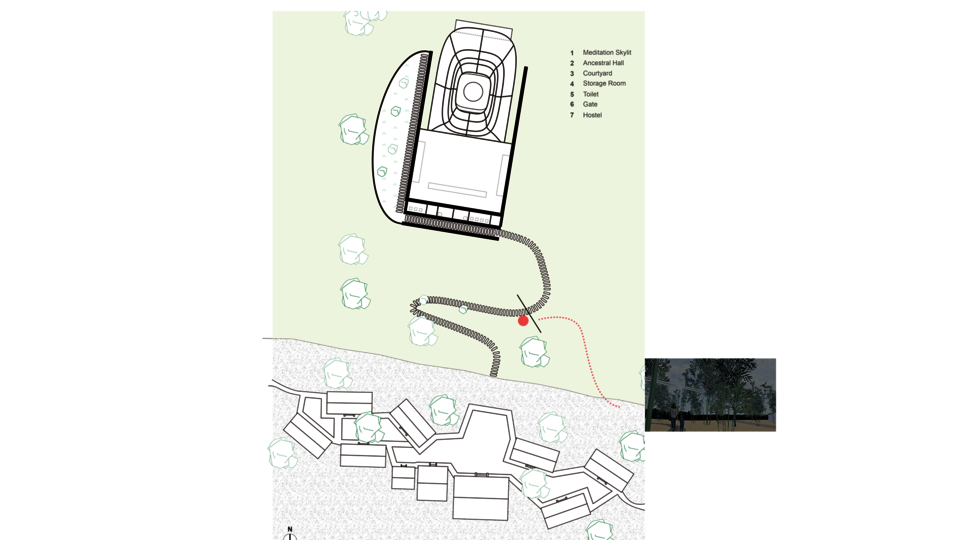

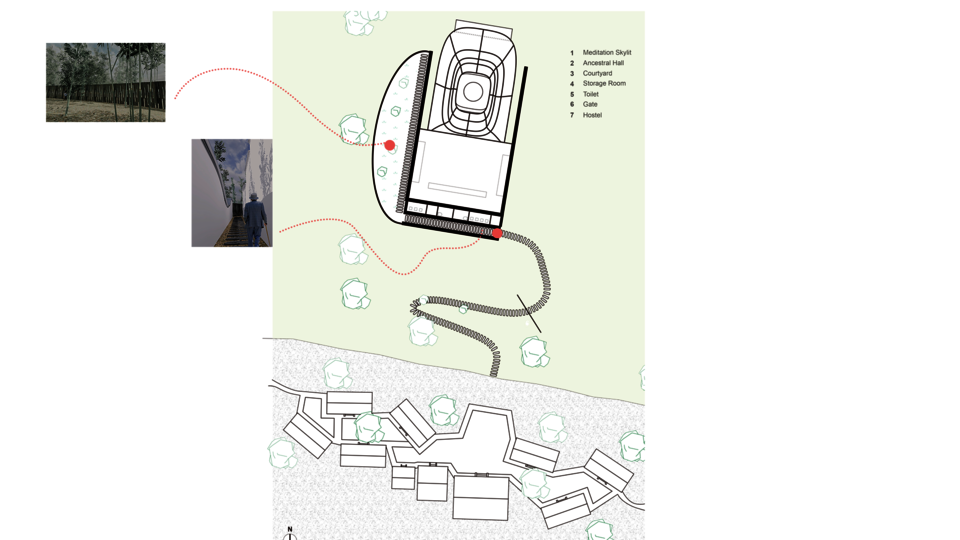

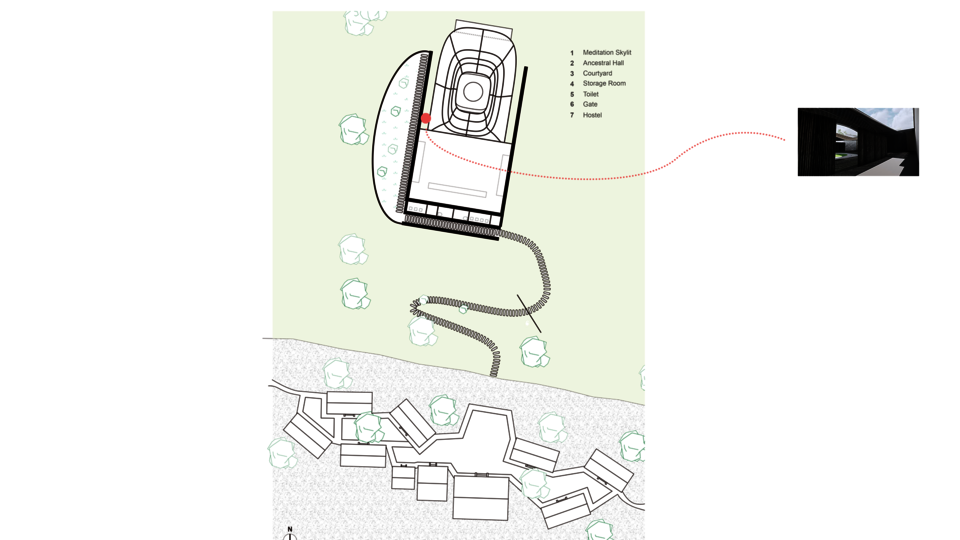

Here the final design map includes hostels, the gate, the ceremony hall, ceiling opening, courtyard, storage room, toilets and a tea space.

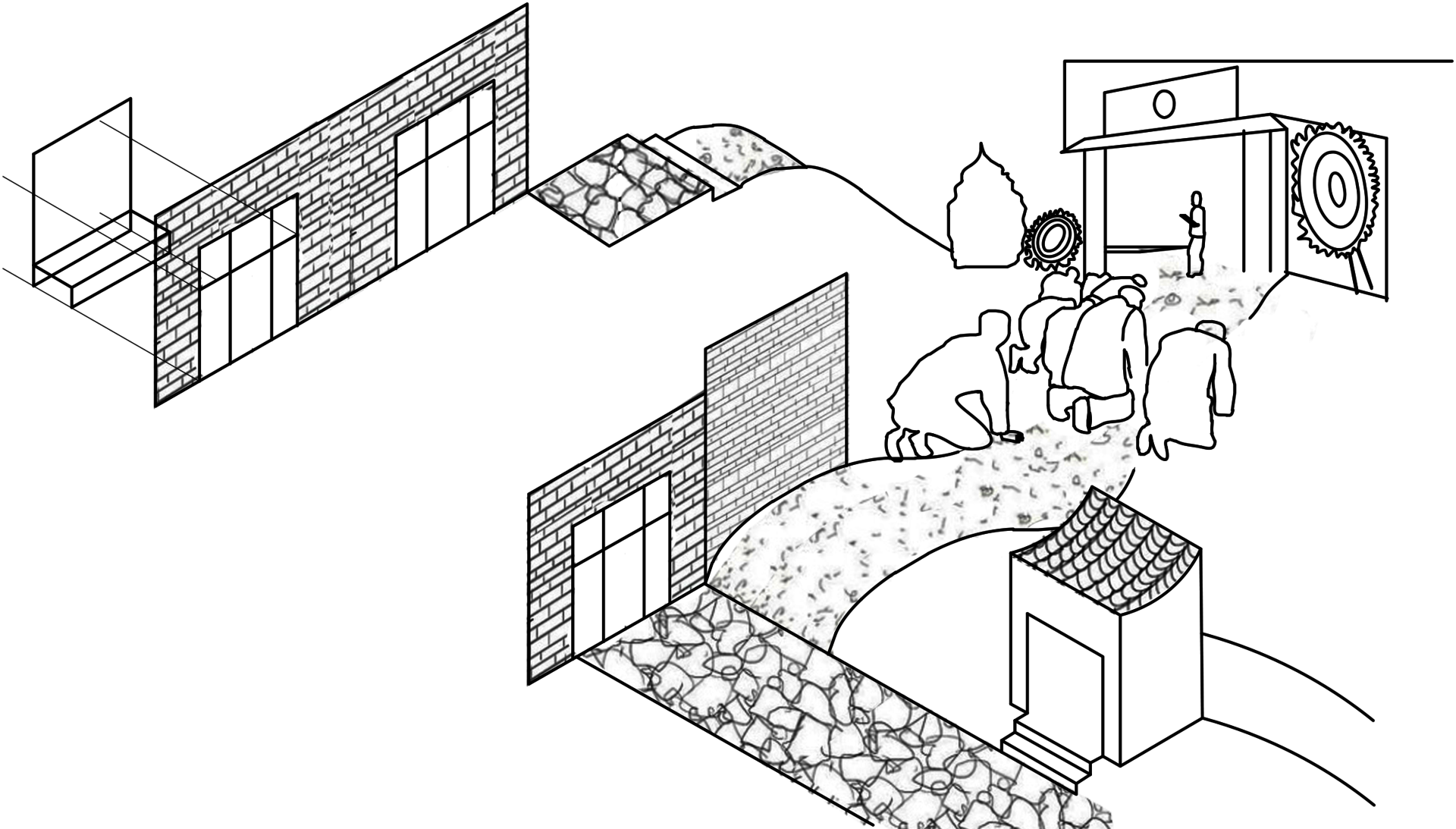

When people come out of the house and pass through this gate, they are entering a new spiritual world -- at least symbolically. They will follow the curved path and then you will enter the tianjin to enjoy the architecture and obtain a sense of calmness. They will then will reach the prayer hall to conduct the funeral ceremony. There will be a ceremony storage room and restrooms in the back. On the other side is an exit, where one may find an outdoor tea room to experience the natural space outside. Here are some renderings that express the whole journey.

JOURNEY

Image

This architectural piece is designed with my Grandfather and his funeral ceremony in mind.

Given this background, I wanted to create a space in which loved ones could gather and mourn their loved ones outside of a traditional burial site.

SADNESS

When the griever leaves their hostel, they are greeted by a long winding path which eventually leads to the ceremony space.

CALMNESS

The path is designed with meditation and time in mind, using a long curving path to take the user on a meditative journey through nature, rather than finding their destination immediately. In addition, the forest conceals parts of the ceremonial building, allowing the user to become immersed in the environment.

FAREWELL

Midway through the path, the user will pass through a gate that resembles bamboo and serves to transport the user to a different space while seamlessly blending in with the surrounding nature.

SHARING

As they approach the building, the user will enter a courtyard, with a fence whose cutouts mimic a river. This is a space to greet friends and family and feel a sense of calm.

HEALING

When the user arrives at the ceremonial hall, they will be greeted with a large open ceiling that allows for plenty of natural light, with the elegant and minimalist blend of nature and architecture allowing for a great sense of peace. Here, the user may sit and enjoy the simplistic open design as part of the meditative experience, and convene with family and friends before entering the prayer hall.

MEMORIE

After the user has completed their meditation and prayer, they are led to a tearoom where they may once again reconvene with family and friends and sip on tea together to complete the ceremonial journey.

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Feng, Qian and Yinghan, Li. Design of Contemporary Cemetery and

Cinerarium Building. Southeast University Press, 2020.

Guxi, Pan. A History of Chinese Architecture. China Architecture & Building

Press, 2009.

Hung, Wu. The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs.

University of Hawai'i Press, 2010.

Xuefeng, Zhang. The History of Chinese Tombs. GuangLing Press, 2009.

Yan, Zheng. Masking Death: Funerary Art of Medieval China. Peking

University Press, 2013.

Yi, Liu. Ancient Chinese mausoleum. Nankai University Press, 2010.

Zhen, Si. “On Traditional Funeral Culture and Modern Cemetery Construction

Of China.” Chinese Landscape Architecture, March. 2009, p. 23.

Zhendong, Liu. The hierarchy of the underworld: an introduction to the

ancient Chinese tomb system. Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2015.