ABSTRACT

This thesis elucidates artistic research on the programmed world and its brutal machines. My practice hones a deviant worldview while confronting ubiquity. Rejecting a vision of progress that rests on exploitation, I aim to destabilize readings of surveillance and policing as beacons of safety. My work proposes models for seeing and knowing from below.

Beam Splitter

Image

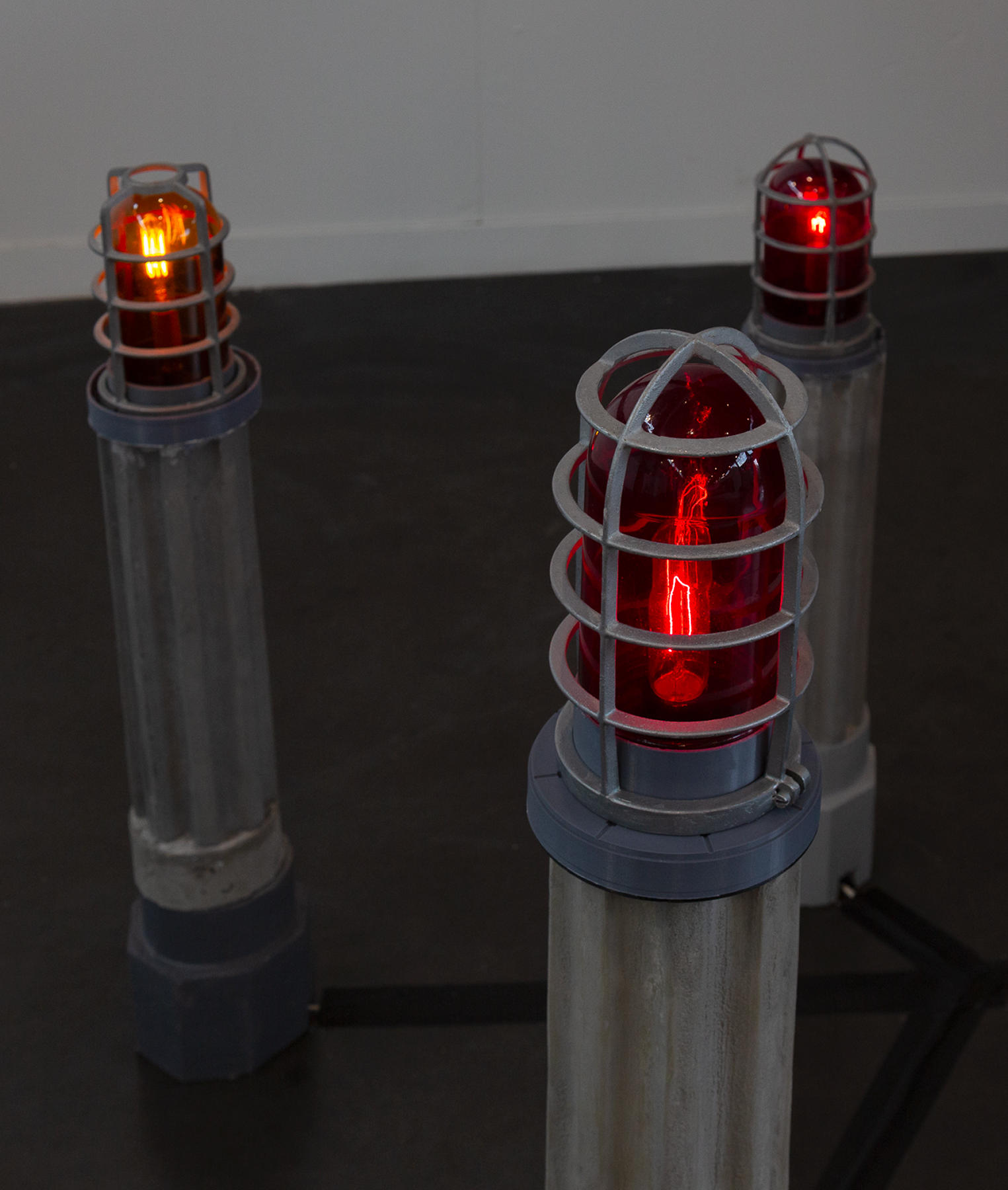

Light Cages

Image

Mercury Bath

Image

False Beacons (Essay)

Through my essay and series False Beacons, I aim to address a misplaced sense of emergency, and to unravel the symbolic correlation between light and safety.

What follows is an excerpt from my thesis book Knowledge From Below (2021).

The dioptric lens, invented by Augustin Fresnel in the 1820s, was first installed in lighthouses as a life-saving measure. Its basic form is a glass bull’s-eye, with concentric circles like steps. This lens, bending light from a single source, could transmit signals through the fog and across long distances. The French installed them at Cordouan lighthouse in 1823. Within that decade, the British, Irish, and Scottish adopted dioptric systems for lighthouses on their own shores and colonies overseas. Fresnel’s invention, a canonical achievement of Enlightenment optics, assured that rapid maritime expansion would follow.

In a treatise from 1859, physicist David Brewster presents dioptric lighting as an unequivocal success. He asserts that the lights “will be hailed on every shore as beacons of mercy to the seafaring world.” 1

It is tempting to romanticize the beacon. Nevertheless, repetitive stories emphasizing salvation obscure the role of lighthouses in colonial projects. Important gentlemen of the 19th century wax lyrical about sacrifices and treacherous voyages, but their stories mask another treachery, which spawns from the idolatry of light.

As clockwork turns the lighthouse lens, beams flash intermittently through an array of prisms and colored filters. Sailors find and decrypt these illuminated signals. The apparatus, piercing through the darkness, resembles the red and blue flashers on police cars.

An 1850 paper from the British House of Commons bears the title “Statement of what measures have been adopted respecting the Erection, Management and Superintendence of Lighthouses in the British Colonies and Possessions.” This document begins, like many of its kind, with a description of perils at sea. The text presents colonial lighthouses as valuable aids in a great logistical challenge. It includes a letter from Hume, who argues that a department ought to be established, to facilitate the exchange of messages among globally dispersed officers. Channeled through an administrative center, naval communications could produce a “mass of information” useful for navigating the sprawling empire. 2

These documents on colonial lighthouses seem to reiterate the same ideology— that Western men can use their inventions, their bright lights, to triumph over nature’s tempests, and to establish control over foreign lands and people. Resistance is missing from most published accounts about lighthouses. Suppose the people already inhabiting Bermuda, Jamaica, Singapore, and other “possessions” opposed the will of British sailors, to see and reach their coasts safely? When seen from below, the spinning light appears neither picturesque nor romantic, but malicious. False beacons become inscribed in history, and intentional erasures smooth out contradictions in the enlightenment fetish, which persists today.

Soon after its incorporation in lighthouses, the fresnel lens found roles in other niches of modern life: railway signal lanterns and police beacons. I walk through Providence and notice small beacons everywhere. I see light fixtures with red lenses beneath the bridges. Blue emergency lamps line the campuses. I pass under flickering street lights in Kennedy Plaza and recognize the surveillance cameras conveniently attached. The flashing lights of police cars glare— piercing through the night, and through my windows. Even when I’m home, I feel constantly surrounded by and reminded of their presence. Spreading light without warmth, the beacons won’t protect us.

1 p38, “On the Life-Boat, the Lightning Conductor, and the Lighthouse” (1859, David Brewster)

2 p17, “Statement of what measures have been adopted respecting the Erection, Management and Superintendence of Lighthouses in the British Colonies and Possessions.” (1850, The House of Commons.)

Image

▲ Three works from the False Beacons series. From Left: Beam Splitter, Light Cages, and Mercury Bath.

Mercury Bath is a hybrid between railroad switch lamp and lighthouse with revolving Fresnel lens.

Video file

Behind the Research and Naming

From the late 1800s through mid 1900s, mercury was widely employed in lighthouse mechanisms around the globe. As faster signaling became necessary to keep pace with steam ships, the mercury float, or bath, was introduced to sustain frictionless rotation of massive, 1st order Fresnel lenses. Lighthouse keepers were routinely exposed to the toxic material while maintaining the apparatus. Mercury Bath is a monument to the Industrial Revolution's tragic, toxic dream of acceleration.

Video file

The tin lanterns in Beam Splitter mimic the form of Victorian era police lanterns, a.k.a. "bullseye" or "dark" lanterns. The blink of LEDs and shutter glass highlights the lanterns' formal resemblance to a camera and evokes their deranged weaponization of light. The supporting structure, of metal pipe and plaster bandages, nods to the ubiquitous form of Providence street lights, which are neoclassical kitsch— fluted like columns, but far from elegant.