JOHN DIXON

ABSTRACT

We’ve come to live our lives on a quest for what we deem as efficiency, but has our view on the matter been focused on the wrong measures? Taking Care investigates efficiency utilizing a variety of different comparative measures through the creation of 8 chairs. When our emphasis on certain variables is shifted, is mass production the most efficient means of making? What about one-off production utilizing local materials? Does industry’s approach to ergonomics focus on efficiencies of the employer while sacrificing those of the employee? Working from a Wendell Berry quote contrasting care to efficiency as a point of departure, this paper seeks to question our obsession with efficiency, and further asks the question, is what we have come to know as efficiency, efficient in the first place?

Efficiency Requires Care, Care Begets Efficiency

The standard of the exploiter is efficiency. The standard of the nurturer is care.

-Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America

I had not even made it out of the first chapter of this book, which had been recommended to me countless times, when I was struck with these two simple sentences. It was as if I had shared the last two years of my mind with the author, and he returned it to me in terms more eloquent and concise than I myself could muster. I grabbed my highlighter, and filled in the text, working quickly yet carefully to not drench the pages with the bath water in which I was sitting.

The pages and chapters that followed, and the subsequent essays and poems I’ve since enjoyed, have continued to speak to my concerns on the contemporary state of things. I was taken aback by his putting words to his issues with agribusiness, that ran so parallel to my own issues with contemporary design. Wendell Berry lives by the manners in which he so passionately speaks in favor of. Yet I kept coming back to these two sentences. Fourteen words, in the middle of a paragraph on page nine of The Unsettling of America.

It is said that the most efficient means of moving a person is by bicycle. I for one am quite the fan of this train of thought, and as such, a number of the following projects were made in close partnership with my bike. Yet in many instances, the way we evaluate the efficiency of a task, system, machine, our lives, runs in stark opposition to the aforementioned statement. When we measure all things, the bicycle wins out, but when the system is built to value some measures highly, and others not at all, we bend the definition of efficiency to fit our narrative. Hence, we don’t all ride bicycles everywhere. Bits of Taylorism remain at the heart of much of our industrial efforts, its valuation of worker engagement, skill development, even safety, often usurped by a narrow minded view of what’s come to be known as efficiency. We drive alone in our SUV’s, make coffee with our Keurigs, and have our toilet paper delivered, because we’ve been told that time is money...as if we are all getting rich.

The inconveniences we’ve come to call externalities, pushed by the wayside for the sake of saving time, have ironically led to us quickly running out of it. It is not what we measure that leads to efficiency, but what we have chosen to not measure that has hidden our inefficiencies.

When the street sweeper “cleans” Allens Avenue, pushing the salt, gravel, sand, sticks, loose gloves, bits of car, and whatever else lie in the center of the road, directly into the bike lane, it is not a demonstration of efficiency. It is dangerous. The cost savings to the municipality in reduced time spent cleaning the road without anything resembling care, are only transferred to added cost to myself and the dozens of other bicycle riders that use this bike lane everyday. I for one have felt these costs in fear for my safety and in the dozens of flat tires i have endured in the 2 years commuting in the bike lane turned litter strewn sandbox.

Riding my bicycle home from school one cold March evening on this very stretch of bike lane, past the Shell Oil Terminal and the 3 wind turbines at the Port of Providence, the reason for this Berry quote’s resonance finally rang true. The statement was wrong. Its wrongness made apparent by my learning of the life Berry himself was living. The standard of the exploiter is the absence of care. However, true efficiency is the signifier of the deepest of care. How could we possibly consider the current state of things, shaped largely by “exploiters,” as efficient?

The earth is finite, and full of systems that claim they are efficient. As we forge ahead, making few if any changes to how we operate, the scope of our problems and the negligence in our measurements come sharper into focus. August 22 marked Earth Overshoot Day* in 2020. The United States of America, hit its overshoot day on March 14th. This is not care. This is not efficiency.

Image

Image

Whence It Came

“Grab an end,” he said, as if I looked as though I wasn’t planning to help. Mike, a man I assume to be around 25 years my senior, heaved his fatter half of the log in the back of his truck making it look light as a feather; while I winced as a ping in my back signaled the brink of blow out.

“Holy hell green logs are heavy,” I said.

“Cut it yesterday,” he responded, as we both climbed back into his truck.

Much to my relief, he backed the tailgate up right to the rear of my van, allowing for an easy transfer of logs between vehicles. “How much do I owe ya?”

“Don’t worry about it, I’m happy to help. Good luck and keep in touch!” We shook hands, something I haven’t done with anyone in over a year now, and I took off back home, being sure to not take any quick turns as the three white oak logs rolled side to side in the rear of the van.

The next few days saw nonstop rain, delaying any log splitting, while I chomped at the bit. Thursday afternoon from the studio at RISD I noticed a break in the clouds. I grabbed my bike and took off for home.

Hatchet, mallet, a series of wedges, and some sore forearms, and the largest of the three logs was split and quartered. Putting my newly fashioned riving brake to use, I knocked the quarters down further still, taking my best stab at achieving the highest yield. With any luck, these three free logs from the side of the road 20 miles south of my house would give me parts for four chairs.

On my first walk through RISD’s 3D store I saw for sale something which I had not been able to buy for a number of years. I was immediately reminded of the last time I tried to purchase this favorite material of mine in my hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio sometime in 2015 or 2016.

I wandered around the warehouse three, maybe four times. I thought I had the place memorized, but maybe I was mistaken. There was rough four-quarter in rift and plain sawn, S4S three-quarter, but for the life of me, I could not find any eight-quarter ash. I swallowed my pride, and circled back to the awkwardly positioned desk in the center of the warehouse.

Choosing to feign confidence, I went to place an order. “Can I have 40 board feet of eight quarter Ash?”

“We can’t get eight quarter ash anymore. The state has determined that some beetles can survive kiln drying in material that thick, so it’s no longer available.”

“I guess we knew this was gonna happen at some point,” I replied, and with a few more words exchanged, I wandered back off to the edges of the warehouse, returning to the racks to think of what I could use in place of Ash.

Back at RISD in present day, I leafed through the pre-cut boards stacked on the industrial steel shelving. I picked out two, eight inch by 48 inch boards, and headed to the front counter. Five and one-third board feet. I had no project in mind for the material, but the surprise of seeing it sitting there on the shelf triggered some sort of hoarding instinct I did not know I had.

I had scrutinized that same aisle in a handful of other big box hardware stores in the past, yet this was my first time visiting a “home improvement center” in my new home state of Rhode Island. My heart was set on inch and half dowels, but I feared they’d only have poplar.

The usual spot held no surprises. Red Oak dowels up to inch and a quarter, poplar up to two inch, a wide variety of smaller sizes in Birch unlike any Birch I had ever bought in any other form…maybe its European?

But stored vertically amongst crown molding, trim, and hand rails, was a product I had never spotted for sale before. The one and half inch closet rods I had always seen for sale in Home Depots around Cincinnati were primed white Poplar. These were unfinished Southern Yellow Pine! In New England! Sold by the foot. The price was awfully high for such a modest material, but Southern Yellow Pine is a species I hold dear. Strong, heavy, and usually affordable, I have made a good many things using Yellow Pine 2x12’s as a raw material...you just have to take your time milling it, and sticker it with care.

I bought 8 feet of closet rod, a handful of three quarter and one inch red oak dowels, and a sheet of luan. I knew my project was on.

How do the means and materials by which an object is made affect its final outcome? And is the final outcome just the object, or everything involved in its make, the behavior its making promoted, and its being promotes?

What began as an investigation into origins, quickly transitioned into an observation on economy, paving the way for a number of additional projects which appear later on in this book. I was to make three distinct iterations of a chair I myself did not design, differentiated by the manners and materials used to construct each version, and leveraging the potential afforded by each mode. My muse would be the J39 chair, designed in 1947 by Borge Mogensen in Denmark. My mentors would be the internet, Jennie Alexander, and my dad.

The three separate iterations of the J39 were to take on subtle changes from the original, afforded and sometimes mandated by the techniques and materials used for each. The limitations placed on each iteration prior to its making resulted in variations in aesthetics, proportions, assembly, character, structure, and so on. My main point of reference was a 3D Cad file on Fredericia’s website, which is clearly intended solely for visualization in interiors rendering, and lacks details which I am confident the real chair has, though I have only seen a J39 chair in person on one occasion...

The only time I’ve ever seen a J39 was in Iceland in 2017.

Claire, Mara, and I had an afternoon to kill in Reykjavik, as we waited for our mini camper to be returned, cleaned, and readied for our week-long trip. A quick survey of the little city pointed us in the direction of Hallgrímskirkja, the city’s famous modern cathedral at the top of a hill.

We stopped to look up at the iconic structure, designed to resemble much of the Icelandic landscape we were eager to see in the coming days, and then entered through a series of doors. Head on a swivel, taking in the vastness of the nave, I stopped just shy of a full 180, and rushed back, just to the right of the doors through which we just walked.

There it was, in the flesh. A single J39 chair. A chair I had grown so fond of, I had actually followed the hashtag, #J39 on Instagram. I had never seen one in person, though was well aware of its wide use in Denmark. But here? A single, modest chair, placed in this iconic Icelandic church which was anything but modest.

As the organ player belted out a slew of long chords, I snapped pictures of the chair, picked it up, turned it over, admired it. The patina and color it had taken on caught me by surprise but it’s reference to the Shaker furniture I had seen countless times before was clear and apparent.

My travel partners circled back and asked if I was ready to go. I hadn’t really seen much of the cathedral, but was more than pleased with the visit.

Analog | Digital | Analog

The J39 was designed by Mogensen in 1947 for FDB, however it is currently produced by Fredericia. Inspired by Kaare Klint’s Church chair, which drew heavily from Shaker furniture from 18th and 19th century America. Intended for standardization and production, it became one of the best selling wooden chairs in Denmark, earning its nickname The Peoples’ Chair. Originally produced in Beech with woven seagrass, it is now most widely produced in Oak with paper cord. It’s beauty, clever design, and function made it the perfect chair to use as a model for Whence it Came.

Analog / Digital / Analog is as close to copy as I could manage using the CAD I had access to. While the originals are Beech or Oak, the availability of 8/4 Ash in Rhode Island, which I had not had access to Ohio for years, made it impossible to pass up.

Kentucky Danish

The influence of Jennie Alexander’s 1978 book and subsequent video, Make a Chair From a Tree on green woodworking continues to this day, as exemplified by Lost Art Press’s reissuing of the book, set for 2021. The book served as a sort of text book for the making of Kentucky Danish, covering what to look for in a log, the tools, and many techniques, in the construction of a post and run chair made from green wood. Kentucky Danish took a lot of work, but that could be lessened with experience. The financial cost: a box of cut nails, $8.95.

Big Box Vernacular

My dad worked as an architect until his retirement a few years back. His can do attitude, abilities to make things with limited tools and materials, and his sharing this attitude and these abilities with me are central not only to this specific chair, but a significant portion of my aspirations as a designer. The self-imposed limitations of Big Box Vernacular brought about a whole new way of thinking for me...fine furniture with unfine means. Could designing furniture to be built from easy to access and learn to use materials and tools which leverage economy of scale and global supply chains, gain a bigger audience for "design?"

Image

Counting Calories

“There are a lot of different ways of building a prosperous society, and some of them use much less energy than others. And it is possible and more practical to talk about rebuilding systems to use much less energy than it is to think about trying to meet greater demands of energy through clean energy alone.”

-Alex Steffen

The chainsaw fells. The loader piles. The truck transports. The mill gives order. The kiln dries. The fork lift stacks. The truck delivers…again, and probably again, and again. My car makes a special trip to the lumber yard and back to my shop. The machines flatten, dimension, shape, and turn…all for the log to become round once more.

There are 31,500 Calories in one gallon of gasoline. One horsepower is equal to the consumption of 641 Calories per hour. For a moderately active man my age, it is suggested I consume between 2,400 and 2,600 calories a day…in reality, I could probably survive on far fewer.

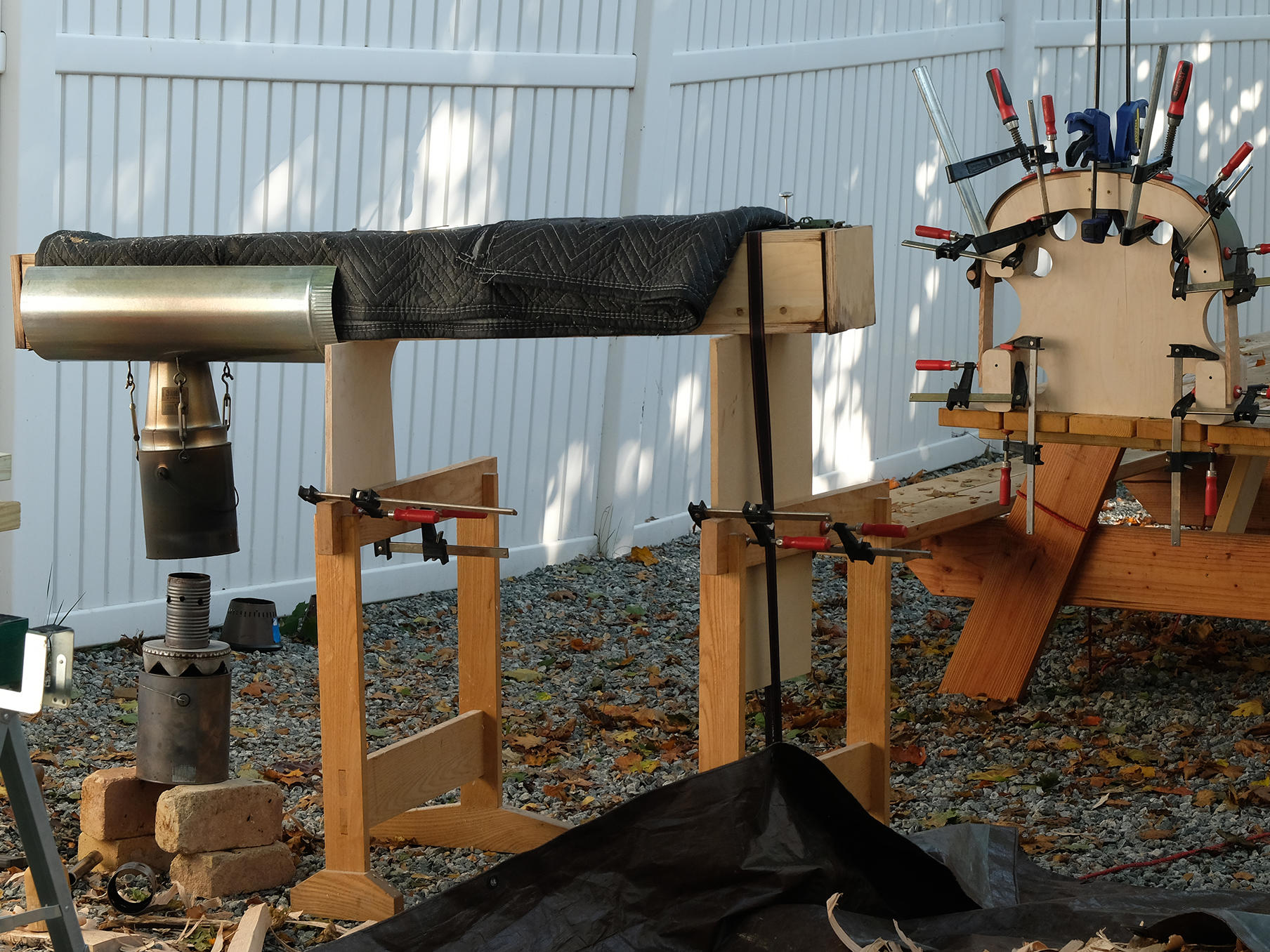

The night before my first big day of Counting Calories, as I gathered up my tools, and finished the last few details to make my jigs and fixtures functional, I struggled with the fact that my Mobile Manual Log Processing Unit (MMLPU) had been built using more energy than the sum total of all the chairs it will ever help create. The task of ‘treading lightly’ had already begun to show its paradoxical truth.

What I had deemed the most appropriate log for my tight schedule lay amongst a massive pile of trunks and branches of lesser quality, all of which had been cut down to make room for a new patio in the backyard of a home in Cranston.

I came across this lot of chair making material listed as firewood on Facebook marketplace, and on my initial scouting trip the week prior, had chosen my candidate. An eight foot long, fourteen inch in diameter Red Oak log, weighing multiple times my own weight. It just so happened to be way on the top of the pile.

The first day of Counting Calories started with a cup of coffee, a quick shower, and a double checking of my tool inventory. I turned my bike around, noting tight turns with the trailer can be treacherous, swung my right leg over my top tube, and took off on the eight mile trek, MMLPU in tow, to the location of the log that would soon become chair.

Passing the Stop & Shop about a half of the way into my ride, I noticed I’d forgotten one important ingredient on my food fueled wood processing exploit...food. A quick pitstop to grab some food, and I was back at it.

As I struggled up Phenix Ave., an all too familiar quick little flick of my right index finger revealed what I was afraid would become the theme of the day...I was out of gears. A few more minutes of struggle, and a bout of huffing and puffing, and I had made it to the log, the pile on which it lay, and my worksite for the day.

Over the course of this long, beautifully sunny Sunday in October, I climbed to the top of the pile, and split the log while it lay in situ being careful not to roll an ankle or roll the log onto myself. I heaved the split log off the top of the stack, quartered it, cut it to a variety of lengths, rived these lengths down closer to their final dimensions and shaved the components down even closer yet. I stacked the wood I would not use being careful to be respectful of the property owner, gathered the chips into the MMLPU’s dry bag, and transported the fruit of the day’s labor via bicycle and trailer, back to my house over three long, slow, fulfilling round trips.

On this most demanding day of the creation of Counting Calories, I consumed 4,511 Calories, which entered my body as an Italian sub, dried cranberries, a 20 oz. Coke, spaghetti, a salad, and hopefully some fat clinging to me from the past.

Thirty-two miles on a bike weighed down with a variety of tools, the MMLPU, 22 rough chair components including redundancies, and all of the waste left over both to fuel my wood steamer, and clean the site. 4,511 calories, 2,500 of which I would have consumed anyhow, and I have the beginnings of a chair, made from a tree whose prior fate had been the wood chipper

What would it take to construct a functional wooden chair using the least amount of energy I could manage?

First, what is functional? To claim the word function as a trope would be an understatement, however, for the sake of this exercise, my pondering over it was truly foundational. While a tree stump may function as a seat, I would argue it does not function as a chair. So that settled it. The key function of a chair beyond a seat, is its ability to easily be handled...so a functional wooden chair would have to be an assembly, so as to be of a manageable weight.

Second, what did I mean by energy? When calculating energy we tend to ignore that of our own. I was set to include the energy I myself spent, and leverage the fact that we as machines, are actually rather efficient.

And last, when and how would I begin measuring? Where does a project begin? I begrudgingly decided the energy used in the creation of the tools I would use could not practically, and therefore would not be calculated. I would begin calculating, when I began actually making the chair. Starting with the acquisition of its material. I was to use an Apple Watch as my means of measurement and tracking, well aware of it’s weaknesses. (And the irony of using such a modern contraption to help make a chair under my own power.) However the intent of the project would not rely on high accuracy, but general comparison.

The first 4 concessions would yield the largest efficiencies:

I could not use my car or any fossil-fueled transportation. I opted instead for the most efficient means: the bicycle. Pulling my Burley trailer, I could move decent size loads with a bit of effort, but little energy use. Not only was I to use what I had figured to be a more efficient source of energy, but I would not be wasting excess on moving the mass of my 2 ton Ford Transit Connect.

I could not use milled and kiln-dried lumber. The energy intensive and inefficient diesel of the mill and natural gas of the kiln mandated the wood be processed under my own power. I would split the chair components from a red oak log, felled a few weeks prior to clear land for a new patio the south of Cranston.

I would have to make the seat from plant matter I could easily find in my near surroundings. For no reason beyond preference, I opted for a woven seat. The materials used in contemporary times for this application are those of import. But the cattail, a grass native to New England found along the shores of its many ponds and swamps, makes for fine, but laborious weaving.

To make the material more moveable and manageable, I would have to work the log down as much as possible in-situ, in order to avoid using energy transporting material which would not turn into chair.

Image

Image

Using a bicycle as transport for myself, my tools, and materials, and tools which were driven entirely by my own power, I was able to produce a chair, all in, with

10,666 Calories...

With one slight exception meant to address 2 dilemas:

1) My design called for steam bending of an integral component making up borth the backrest and arms, and providing a significant amount of torsional strength.

2) I had a lot of scrap wood leftover, primarily in the form of draw knife shavings, that left to their own devices, would ultimately lose a significant portion of their stored energy to methane...a serious greenhouse gas.

Pushing my obsession for Calorie counting aside, I realized I could respond to both of these dilemmas at the same time. A few days of research into home production of biochar revealed that my wood steamer could at least hypothetically be powered by a homemade stove, burning my scraps in an oxygen starved environment, and capturing a large portion of the carbon they contained in a very stable form.

Image

Image

Image

Image

The Next One

Just before Xmas I managed to aggravate an old back injury which put me out of action for over a week. While visiting a physiotherapist in Woodend I asked him his opinion on the best seating position for me whilst I recovered. He responded immediately, ‘the next one.’

-Glenn Rundell, chair maker

The task chair held my torso like a back brace I’d never been prescribed. I settled in to the sore, stiff, weak, familiar feeling of office brought on atrophy. I had interned there for three months and I was twenty-two years old.

Much to my parents’ dismay, my long history with and addiction to BMX (bicycle motocross), had led to a wide array of injuries. Broken arms, ribs, hand, and leg, torn ACL’s, dozens of stitches. Yet I had not ever thought these activities were killing me. But here I sat in my office chair, poised in a position of utter inactivity, and I felt like I was dying.

The prospect of a normal, professional, aspirational career brought about the guarantee of security but not comfort, and certainly not health. The degradation of my body in these three short months foreshadowed a future I could not get myself to bear.

Two years, a college graduation, and half of a recession later, I found myself working in a machine shop in conditions and manners that by contemporary standards would be considered drudgery. I felt better than I ever had. I found myself sore after work. Not during it. Gone was the atrophy. Gone was the chair shaped back brace. Gone was sitting.

The feeling of weakness had been replaced with one of strength. The hunch in my shoulders had been replaced with a stance of pride and better posture. And the nagging pain in my stomach, for which I had feared chronic illness, had been long forgotten. It is of great irony that my new found job, which literally contained the word machine in its title, had made me feel more human.

For 5 years I worked making forklift parts, none of which was ever descriptive enough in its design or name to hint at its final function. It was hard, hot, loud, and smelly. However it was not back breaking. The turning of vice handles and allen wrenches gave my hands strength they had never felt. The carrying of coolant buckets and parts bins translated into core and leg strength which no amount of BMX could ever have created on its own. It was work. And though it didn’t make my wallet feel right, my body had never felt better.

The shift in careers had left me making less, and sitting much more, but the class with George Sawyer brought back the feelings of real work. The odd little stool was tucked underneath the longer of the two workbenches. It wasn’t so much as in storage as conveniently placed out of the way to not take up any of the precious little floor space.

“What’s this?” I asked, as I pulled it out and looked it over.

“Oh, the perch?!,” George let out with his infectious excitement he showed over many of the things in his shop full of treasures. “Peter Galbert and Curtis Buchanan designed that in partnership with someone who does research into ergonomics.”

The perch and the form it took were new to me, filling me with excitement and curiosity. Though a concept not of his own, I was certain this particular example was George’s personal take, as the turnings were clearly of his style.

As I sat down in the perch, I was put in a position I had never felt before. My hips rolled forward, my feet planted soundly into the floor, and my spine curved in a way I had only seen in anatomical illustrations. My new found posture and bodily position made me immediately aware of who this unnamed researcher was.

Earlier on in this very same trip, while in a hotel in Rhode Island, I had finished reading The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body, and Design, by Galen Cranz. A particular quote from the book came immediately to mind. “The optimal solution is not a better design of the components of the chair itself, but rather reconfiguration of the chair itself to allow a fundamental change in posture.”

I was certain that this design was her research made manifest in physical form.

In a quest for efficiency I kept coming back to my experiences working in an office setting. Sure my supportive chair task chair made me more productive at my computer. But its adverse affects on my body didn’t cease when I went home at night. The quantitative costs would be hard to measure. If I had stayed in that job for my whole life would it have lead to increased medical costs down the road? Blood clots, weight gain, back problems, loss of flexibility... The qualitative costs were clear however. While the work was interesting, the stagnation it required was lowering my quality of life, both in the office and out. Sore back, sore wrists, sore...guts? However difficult to totally count, I determined the costs to my health far outweighed the benefits I could possibly make to my employer. On a search for research that challenged what I had always thought of as “ergonomic,” I stumbled across the work of Galen Cranz. In her book, The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body, and Design. She specifically mentions all of the symptoms I had developed in my short time in that office years before. The answers were surprisingly simple, and I had already discovered many of them through intuition, avoiding the office at all costs. The postures which we employ are in desperate need of change. When we think of a typical day, next to lying down while sleeping, we spend most of our time sitting. Is this humane? Is it even human?

Image

As I make my way up the overpass, I feel a slight forward nudge from the trailer following every stroke of the pedals. My oneness with the machine reminds me of my use of the bicycle and all its versions, as a means of explaining ergonomics to my former students.

“You don’t enter a race with a beach cruiser,” I would say.

A second later, I round over the top, and with a wide right turn, coast down into the Home Depot parking lot. With the sudden urge of a vocabulary refresher, I get out my phone and search “ergonomics” in Google.

The very first result is from Oxford Languages and couldn’t be more appropriate: Ergonomics (n) : the study of people’s efficiency in their working environment.