ABSTRACT

This Trash is Someone Else’s Problem reimagines object design practices through a decolonial lens that embraces responsive approaches to the local environment and the communities that steward it. It advocates for design justice and social equality. The physical work was developed from discarded scraps of industrial waste harvested from the Providence area, such as wire fencing, oil drums, rebar and steel tubing. It was created without the use of expensive tools, machinery and materials in favour of a less extractive approach to design. In conjunction with the studio work is a series of community gatherings focused on low-fi ceramic pit firing and salon style discussions. The event series was developed to share the core ideas of the thesis with the larger community and establish a deliberately informal learning environment centered in the principles of listening and gratitude.

Providence Project

Eyes Closed, Ears Open

The pandemic spread quickly across the small state of Rhode Island. After three weeks in my tiny apartment I resolved to drive home to Canada to wait it out amongst the lakes and the trees. When I arrived in early April there was three feet of snow, a frozen lake and a cord of chopped wood for the fire. It was quiet, cold and off course. One month later the snow had cleared. I watched the ice on the lake slowly melt, then come back, then melt again until the entire body of water was freed from it’s winter shackles. Buds became visible on bare trees and almost overnight the birds returned. I first started hearing them in the wee hours of the morning. The blackcapped chickadee calling out chickadee-dee-dee-dee through the leafless trees. The Eastern Wood-Pewee slurs a cheerful pee-a-wee from a young maple beside the deck. Each morning I would be engulfed in the developing cacophony of spring. I spent hours sitting in the cold with my eyes closed and my ears open. It can take decades to learn to identify birds based on their calls. Some lifelong birders never reach the point of confident auditory identification.

I clattered around the hall cupboard filled with heavy coats. Behind a box with flashlights and screwdrivers I found my grandfather's old field glasses. The case was tattered and the strap long gone, but the binoculars afforded me a new level of observation, a way to connect with the physicality of the sounds that had been holding me all spring. I ordered a book on Ontario birds and slowly began to connect the sights and sounds to knowledge. Robins and crows, kinglets and wrens, I was grateful for their company. I watch the female loon float around the bay with a baby chick on her back. Occasionally her baby would slide on to the water's surface as she dove into the depths in search of minnows for breakfast. Loons sleep with their necks tucked in, drifting about with the currents and the wind. When I come too close in my canoe, she belts out a tremolo call, warning her partner of my presence. We are all talking to each other even if we don’t speak the same language. Nearly a year later the birds are returning to my backyard in East Providence. My ears have been tuned to perk up at the sound of a squawking jay or the hammering of the woodpecker I haven’t been able to glimpse. I can’t always see them, but I am listening so I know they are there.

Listening is a practice because it takes deliberate work. Our ability to multitask within our own minds is truly extraordinary but not necessarily beneficial. Listening, like meditation, requires you to be present. I can watch television, work on ceramics and simultaneously have a conversation with my roommate, but should I? What was that thing she mentioned? Did I remember to score and slip that section? What just happened? Okay now I have to rewind. To offer one's full attention at all times is impossible as modernity has not afforded us more leisure time but rather more distractions. Developing a practice of listening is to narrow one's focus in a world that requires us to be working on five things at once. From the birds in my backyard, to the many voices I spoke with for this project, I have been exercising my ability to listen and cultivate knowledge. As designers, we are often positioned as experts of our field. A practice of listening acknowledges everyone’s expertise based on their own lived experience.

When I arrived at RISD in the fall of 2019, listening was not my strong suit. My professors admonished me for pressing forward too quickly, not really doing the design work, not listening to the feedback I was given. “You need to enjoy the process more. Slow down. Do the work”. I was impatient. I wanted to develop new ways of thinking but remained rigid in my approach. To ensure I would make beautiful designed objects, I would stay firmly within my lane.

Something fundamentally shifted after my summer alone with the birds and the whispering pines. I didn’t have a lane anymore, at least not one that I recognized and I could not separate myself from this practice that had carried me through the summer. By listening to everything around me my perspective shifted organically. When I returned to Providence, I noted the sound of the river from my apartment, plastic bags and leaves smushed along chain link fences, masks strewn across public walkways and heaping piles of garbage along the train tracks.

My capacity for listening was expanding to my other senses where seeing and feeling became a form of listening. On the first day of classes I walked by the big blue bin outside the sculpture foundry. I had passed this bin everyday the year before and had never given it a second thought. This time, when I approached it, the sun was casting its last rays of the day on the alleyway behind our studios before dipping behind the Metcalf Building. It was as if the container was glowing, light refracting off misshapen and abandoned projects. The bin was signaling to me, drawing me toward the limitless possibilities within it. I put on my welding gloves and began dragging out rusted metal scraps, contorted, some haphazardly fused together. I found a wide piece of steel tubing, some rebar and some steel rod a student had bent into a squiggly shape. I took these items to the mig welder and made my first piece of the year. It was a chair, it was sittable and it was like nothing I had ever made before.

I was actively unlearning while simultaneously knowing more. The materials were speaking to me, telling me how they should be processed and shaped. It was as if they had always been trying to talk to me but in a frequency I could not hear. Suddenly, I heard everything. I could recognize my lane again and it was going in a completely new direction. I decided that day I wouldn't go to the store anymore. There was nothing I needed that I couldn't find in my surroundings. Undervalued items everywhere. Pure potential tossed in the ditch while thinking, this trash is someone else's problem. Maybe it could be my problem. I could create second chances and see value all around me. All I had to do was listen.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

The Providence Project was developed with the intention of highlighting under-represented models of production and undervalued material resources. Made entirely from salvaged, discarded material harvested from the Providence area, I aim to draw from my surroundings, a narrative of what Providence might look like as furniture. Individual pieces of steel were found, collected, processed with oxy-acetylene, connected through a MIG welder and spray painted.

Hot Talks

Nothing Left Unthanked (excerpt)

A fire is a place to be present, to share, to listen, to observe. As the flames mesmerize with their dance and traces of smoke fill your nostrils, you are met with feelings of nostalgia and warmth.

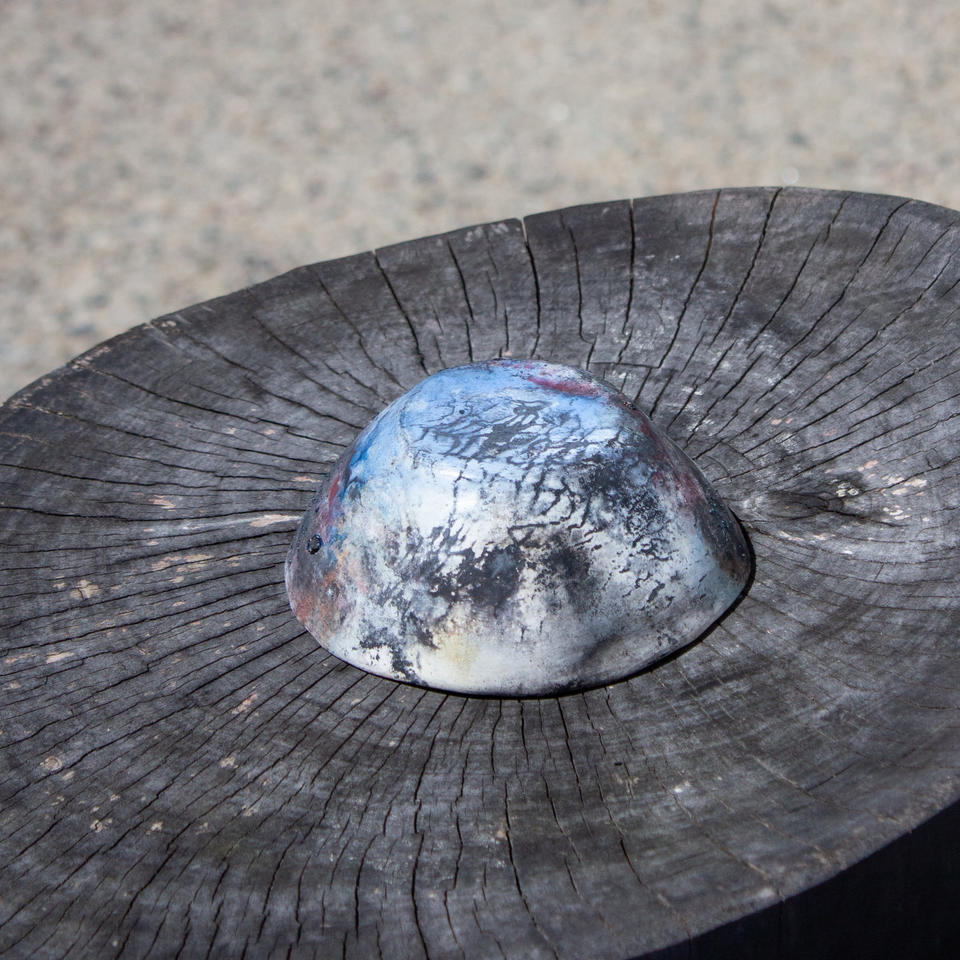

Pit firing is the oldest known method of firing ceramics and is still widely practiced around the globe. It employs aspects of the natural environment in the process of making and cultivates sensations of experimentation and play. Hot Talks is a recurring community gathering and ceramic pit fire event. The goal of Hot Talks was to create a space to practice gratitude, foster community and engage participants in a deliberately informal learning experience. We begin by loading a pit with various organic materials and colorants. Coffee grounds and salt soaked corn husks. Seaweed and copper carbonate. Sawdust and wood scraps fuel the flames. Everyone gets a chance to add something to benefit the firing. Before we ignite the first flame, I ask everyone to join around the pit with some seaweed in their hands. We all take a moment of reflection and express gratitude for an element in our lives as we toss the seaweed into the pit. We watch the flames as they engulf our blend of gathered materials. I close the lid and turn on an air mattress pump I have fixed to a long steel tube punched with holes. The pump keeps a steady flow of oxygen to the fire and we reorient ourselves for a discussion.

The first time we spoke of the land. I told the story of King Philip’s War - a story of genocide and displacement. We spoke of street names and colonial powers. Land acknowledgements and institutional change. Everyone listened and everyone shared. The next time John told us about the many ecological benefits of biochar. He read us a story and brought out a stove he fashioned from coffee cans to show us how biochar is made. We spoke of carbon emissions and climate change, of afforestation and governmental oversight. Everyone listened and everyone shared. At the final Hot Talks, I asked the group to reflect on the idea of ceremony. What makes a ceremony and what kinds of homemade ceremonies punctuated their lives. We spoke of intention and personal growth, of religion and past lives. Everyone listened and everyone shared.

Hot Talks itself is a ceremony unbound by time and place. Like the trees in the forest, linked through complex subterranean networks, Hot Talks weaves a potent web of reciprocity and connection not visible from the surface. It invites you to visit a space less precious than the studio. Somewhere where there are no mistakes and we can learn collectively. I hope to continue hosting Hot Talks, here in my backyard throughout the summer months. I hope to take Hot Talks with me when I move away from this place. I hope others who have participated continue to talk, make and work collectively and cultivate ceremonies of their own. Just like mornings on the mat, it’s about making space for gratitude to flow in and let it fill the gaps between us. Hot Talks is to be continued.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

50% Off

When I go to the grocery store I head toward the reduced rack. The location varies from store to store but it can often be found tucked away somewhere inconspicuous. The rack is occupied with items the store clerk has deemed unsuitable for full price sale, mostly produce on the brink of expiration. But sometimes the items found there are not on their last legs at all. Sometimes the produce is fresh, crisp, bright, and teeming with delicious nutrients. So why were these perfectly good fruits and vegetables plucked from heaps of others like it and placed in the no-man's-land between the bread and fish sections?

If you have ever grown anything at home you understand the reality of food production is not to generate a crop of uniform items without imperfections. A tomato has no true platonic form. As long as it comes in healthy and a squirrel didn’t snatch it, it’s a success. In Indigenous agriculture, the practice has been to modify plants to fit the land while using biodiversity to support a healthy ecosystem. For generations, Indigenous Peoples have cultivated a variety of plant species at one time, practicing a polycultural approach. Polycultures are not only less susceptible to pest outbreaks than monocultures, but the diversity of plant forms provides habitats for a wide variety of insects and animals. Modern agriculture takes the opposite approach, modifying the land to fit the plants, cultivating straight rows of a single species.

At the store, fruits are homogenous, herbs come wrapped in plastic boxes and tomatoes have no flavour. The modern food industry creates antiseptic clones, and we have bought into it so much that an apple with a funky shape gets a 50% off sticker or is tossed aside completely. Why do we maintain such a narrow view of what is acceptable? Our inability to recognize the possibilities that lie beneath the surface, stretches far further than food. We love to tell a single story.

Julia Watson outlines in Lo-Tek (2019), “Practices such as monocultures, excessive tilling and the application of artificial fertilizers and pesticides are being linked to the deterioration of soils, depletion of aquifers and the global collapse of bee populations which are critical to pollination.” When the British colonists initially encountered the Indigenous gardens in Massachusetts, they inferred that these first peoples did not know how to farm. They were wholly unable to fathom the multifaceted and holistic approaches that characterize Indigenous cultivation practices.

The Three Sisters are a companion planting technique that involves cultivating corn, beans, and squash together. The corn provides the structure for the beans to climb while the beans contribute essential nutrients, like nitrogen, to the soil. The squash comes in last providing ground cover, shielding the soil from excess sunlight and creating a microclimate for moisture. I have often found myself travelling through the Greenbelt of Southern Ontario, a protected region of watersheds and farmland between Toronto and Niagara Falls. Consecutive rows of analogous forms extend for miles, sheathing the urban landscapes of the Golden Horseshoe. Corn, soy beans, wheat, and barley, neatly arranged in single file with none of their Sisters in sight.

Our greatest social vulnerability is also our most considerable blind spot. Monoculture farming practices can be used as a metaphorical framework for understanding the devastating risks imposed by the single story of Western colonialism. It comes as no surprise that an economy predicated on extraction and accumulation, maligns the sacred. Today’s worlds, such as those of settler colonialism in North America, were constructed to provide privileges to their descendants including the agency to dominate and inhabit Indigenous lands. A destructive narrative has been crafted to lead the privileged to believe that it is legally and morally acceptable to do so. Former U.S. senator, Rick Santorum, recently stated at a right wing students’ conference that American colonists built this nation from nothing.

“There was nothing here. I mean, yes we have Native Americans but candidly there isn’t much Native American culture in American culture...We came here and created a blank slate, we birthed a nation from nothing”.

Colonial ancestors granted their offspring the worlds in which they could feel themselves to be innocent saviors of Indigenous peoples. Santorum’s comments not only negate the millenia-long presence of Indigenous peoples and the genocide inflicted upon them by European settlers, but it also perfectly exemplifies the white colonial mindset. They have constructed a fantasy in which they were protagonist heroes while the free market would be their eraser.

Designers today face a variety of complex problems that require multifaceted and adaptive responses. In the face of environmental and social collapse, design at the intersection of anthropology, sociology and ecology is the most urgent discussion of our time. We cannot possibly do right by every living organism, however we can shift our perspective to one that focuses on long term ecological impacts above short term financial gains. Adopting a polyculture of knowing requires a radical shift from practices rooted in extraction and intrusion towards a system of diversity and inclusion that actively seeks liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems. The Three Sisters exemplify the benefits of a mutual support network where the contributions of the individual are not fully expressed until they are nurtured together. The Sisters rely on each other’s unique gifts in order to thrive collectively.

Bottom of the Barrel

Image

The idea to free pour bronze came just like everything else. It was suddenly so obvious that was the way to finish the table. I endeavoured to bring more value to the materials while continuing to work in the spirit of spontaneity. Free pouring the bronze was as playful as it was experimental - discovering the perfect temperature so the bronze would slump just so. The molten metal filled in the holes that were caused by rust and repeated hammering. It wrapped around the bottom of the barrel like a fungus. Little bubbles popped wildly as the hot metal hit the cold concrete floor. I turned the pieces right side up and continued to pour, allowing the metal to find its place along the surface. Sometimes we do things because we think we should. Sometimes we do things because it’s what we were taught. Sometimes we do things almost by accident and it ends up being the most illuminating thing we have ever tried. This was the culmination of my shift of methodology. Surrendering control of the process, allowing the materials to just be. I learned to be less precious and in doing so I discovered these materials have an agency of their own. We just have to give them space to exist and ourselves the space to enable it.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to my thesis committee members, Emily Cornell du Houx, Patty Johnson and Lane Meyer.

To Douglas Borkman for helping me pick through piles of garbage and giving me the space to experiment and play.

To Stephen Slaughter, Lóren M. Spears, Karen Houle, Tanya Aguiñiga and James Miller for speaking with me and helping these ideas take shape.

To my classmates, John Dixon and Eric Loucks for your help and guidance.

To my family, Mom, Dad, Craig and Kelsey.

To Ayumi Kodama for your essential graphic design expertise.

To P.J. Couture for driving out every weekend to document the work.

To Anna Dawson for your documentation assistance.

To everyone who participated in Hot Talks, this project could not have happened without you.

To Shauna Jean Doherty for editing this text.

BIBILOGRAPHY

Winona LaDuke and Deborah Cowen, “Beyond Wiindigo Infrastructure,” South Atlantic Quarterly 119:2 (April 2020).

Richard Luscombe, “CNN urged to fire Rick Santorum after racist comments on Native Americans,” The Guardian, April 26th, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/apr/26/rick-santorum-native-am….

Robin Wall-Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants (Milkweed Editions, 2013).

Julia Watson, Lo-Tek: Design by Radical Indigenism (Taschen, 2019).

Kyle P. Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crisis” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, Vol. 1 (2018).