ABSTRACT

In 2016, the Chinese American Restaurant Association recorded a total of 50,000 Chinese restaurants operating in the United States, far exceeding the number of McDonalds, Burger Kings, KFCs, and Wendy’s combined. In the near two centuries that Chinese people have been a part of the American fabric, our food has become one of the country’s most popular ethnic cuisines. While these restaurants stand as testaments to the tenacity and entrepreneurship of the Chinese immigrant, they are also reminders of the centuries of adversity Chinese Americans have endured. The racial divisions triggered by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 have resulted in fluctuating attitudes towards Chinese American culture and cuisine, influenced by factors having nothing to do with the food itself. Now more than ever, with the rise in Asian American and Pacific Islander related harassment and attacks, a reckoning with this troubled past is imperative.

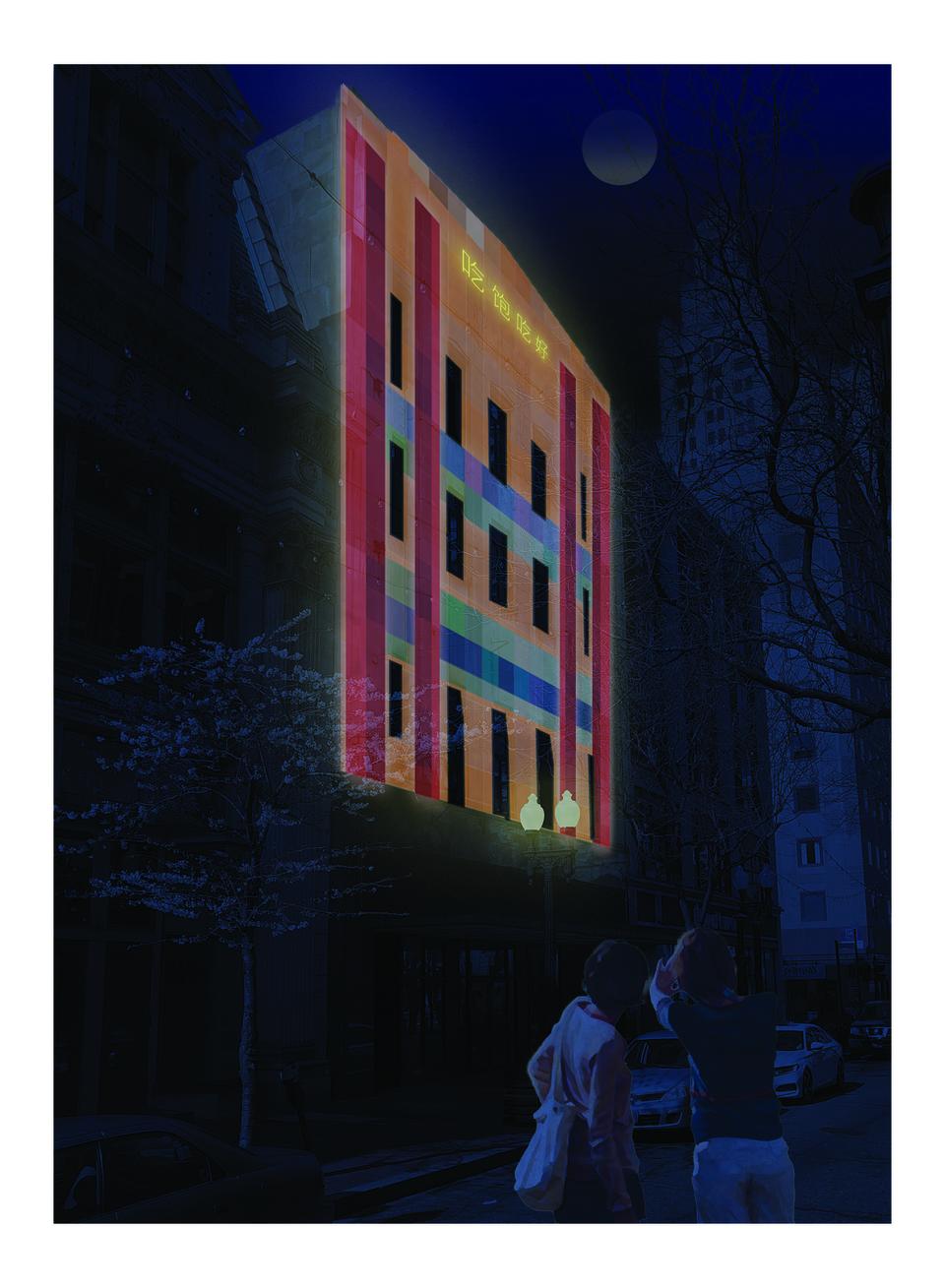

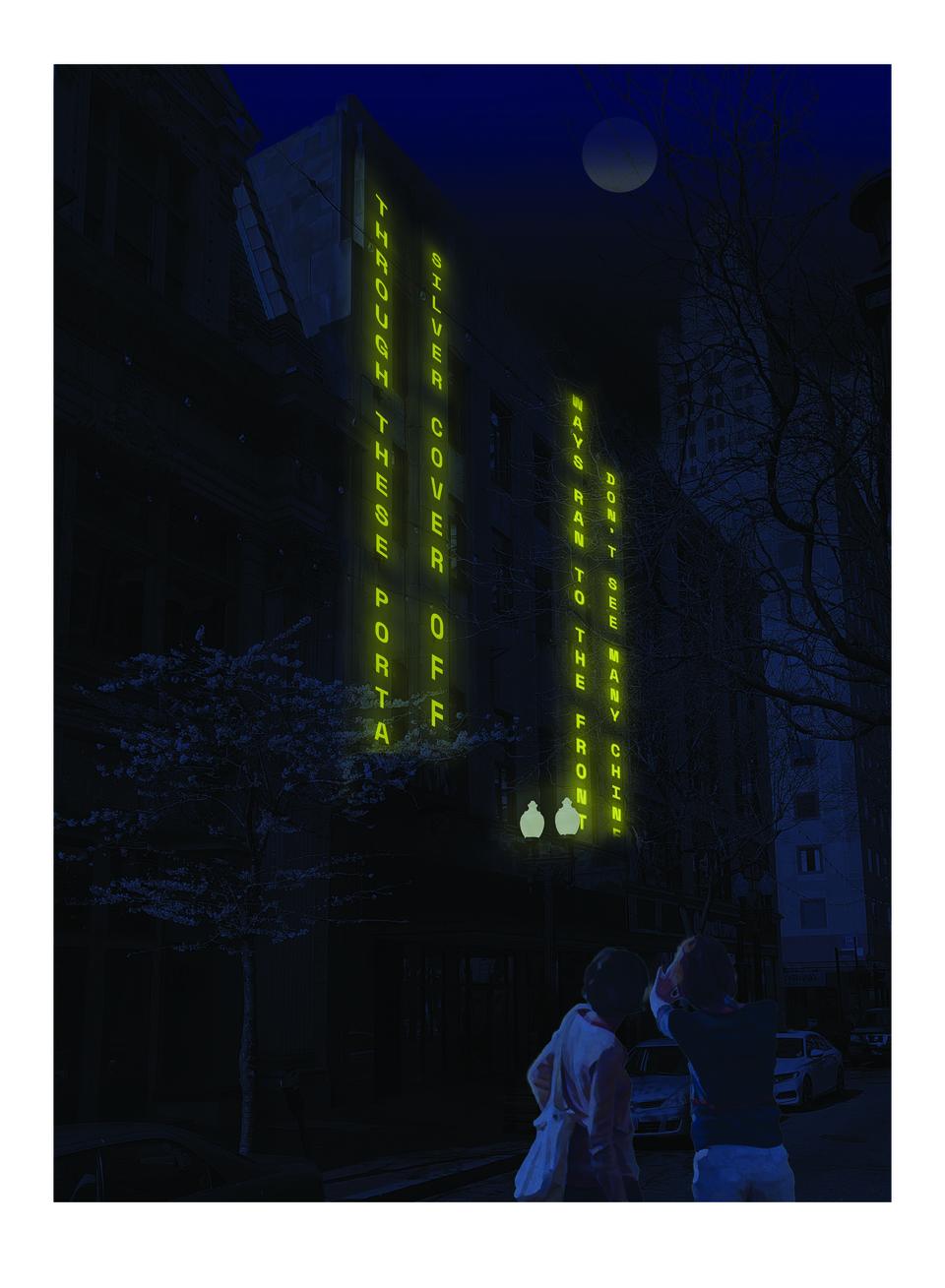

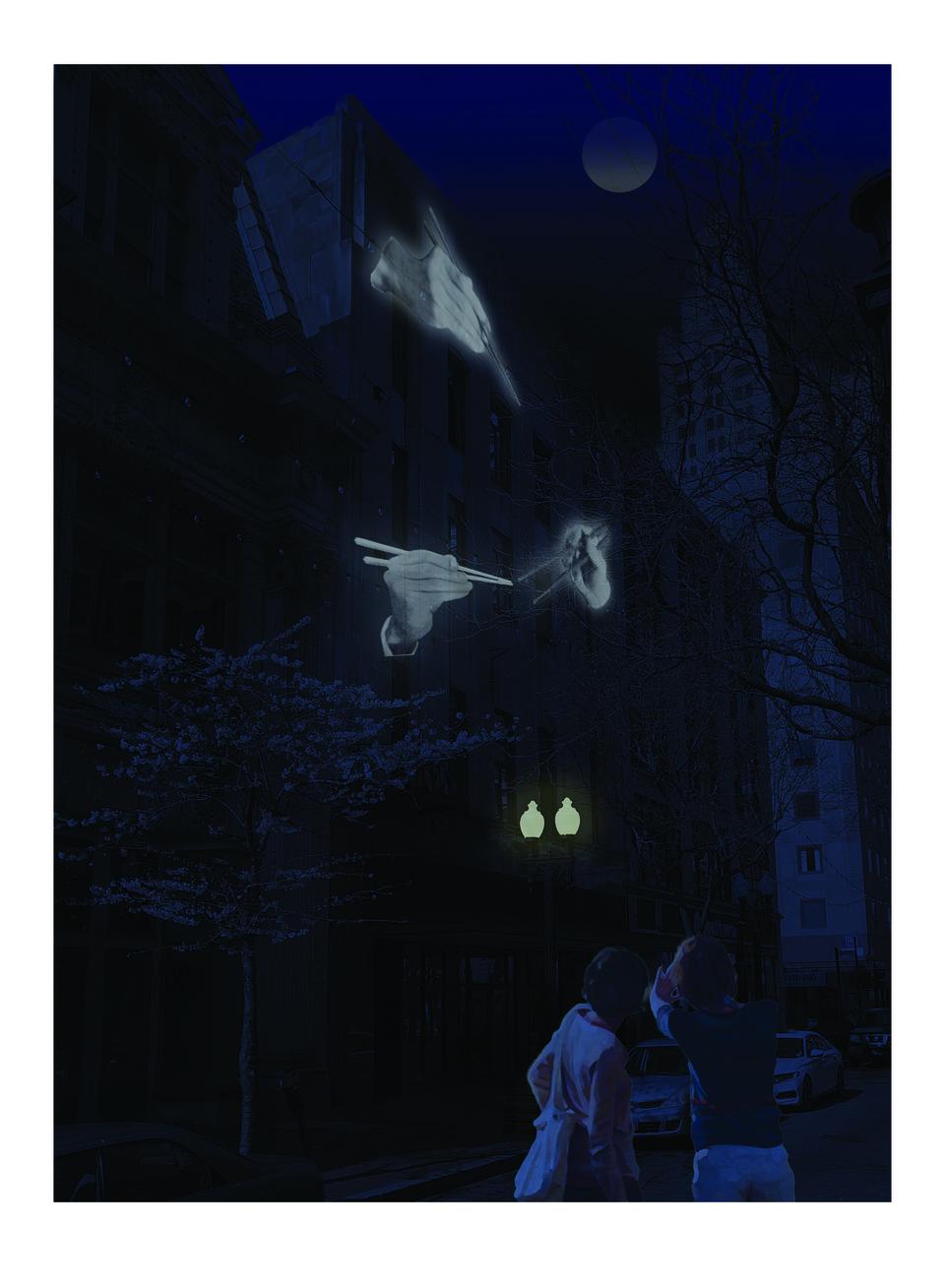

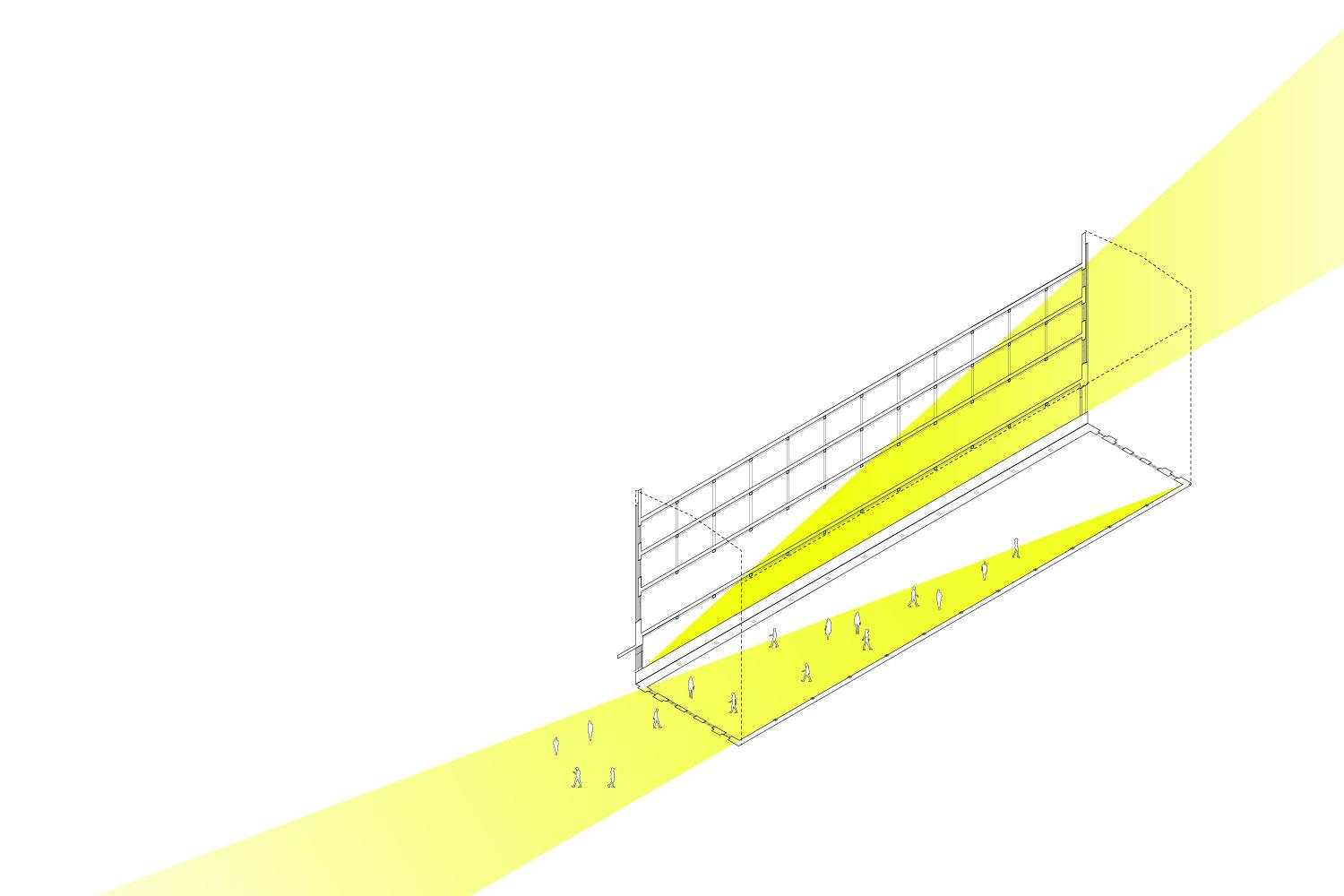

Downtown Providence was once home to a small, yet prominent, Chinatown. In 1914, Chinatown was razed as part of an urban renewal effort rooted in discriminatory immigration policies and racial biases. While this Chinatown’s presence lived on through a revolving network of Chinese restaurants, suburban flight and economic decline forced many of them to close in the 1980s. Most traces of this cultural enclave have disappeared and with them the loss of a communal identity for Chinese Americans in Providence. The Art Deco Kresge Building on Westminster Street sits on the former site of one of these bygone restaurants, the Chin Lee Corporation. Using digital projection as an ephemeral intervention, a series of illuminated images scattered throughout the downtown area and superimposed onto the Kresge Building's facades will enliven Downtown Providence and transform it into an urban canvas. Each provocative image tells a narrative that recalls the cultural memory of this forgotten community and moment in time and encourages the public to question notions of identity and history.

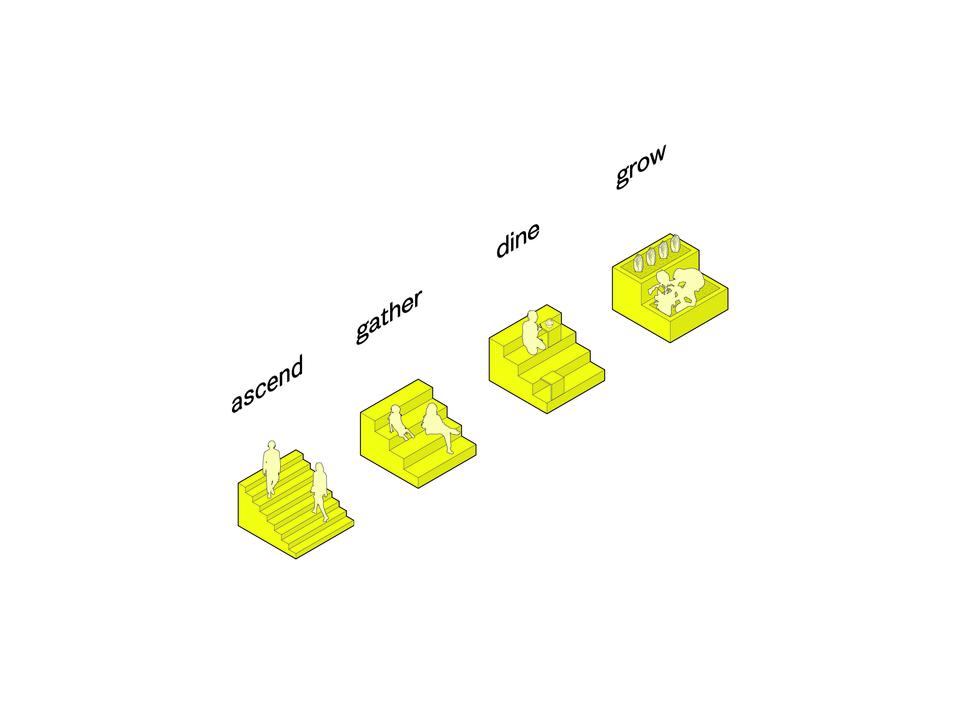

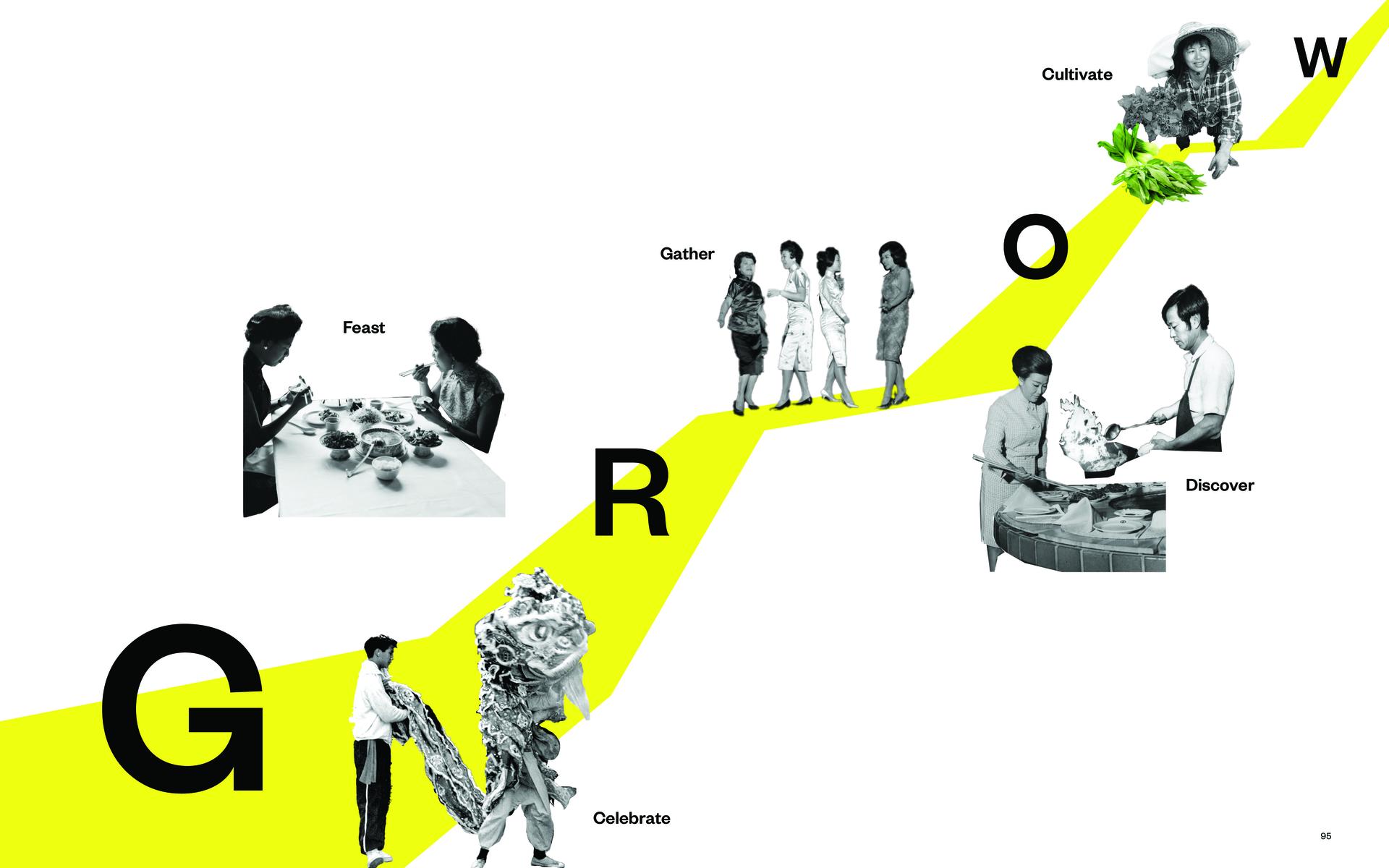

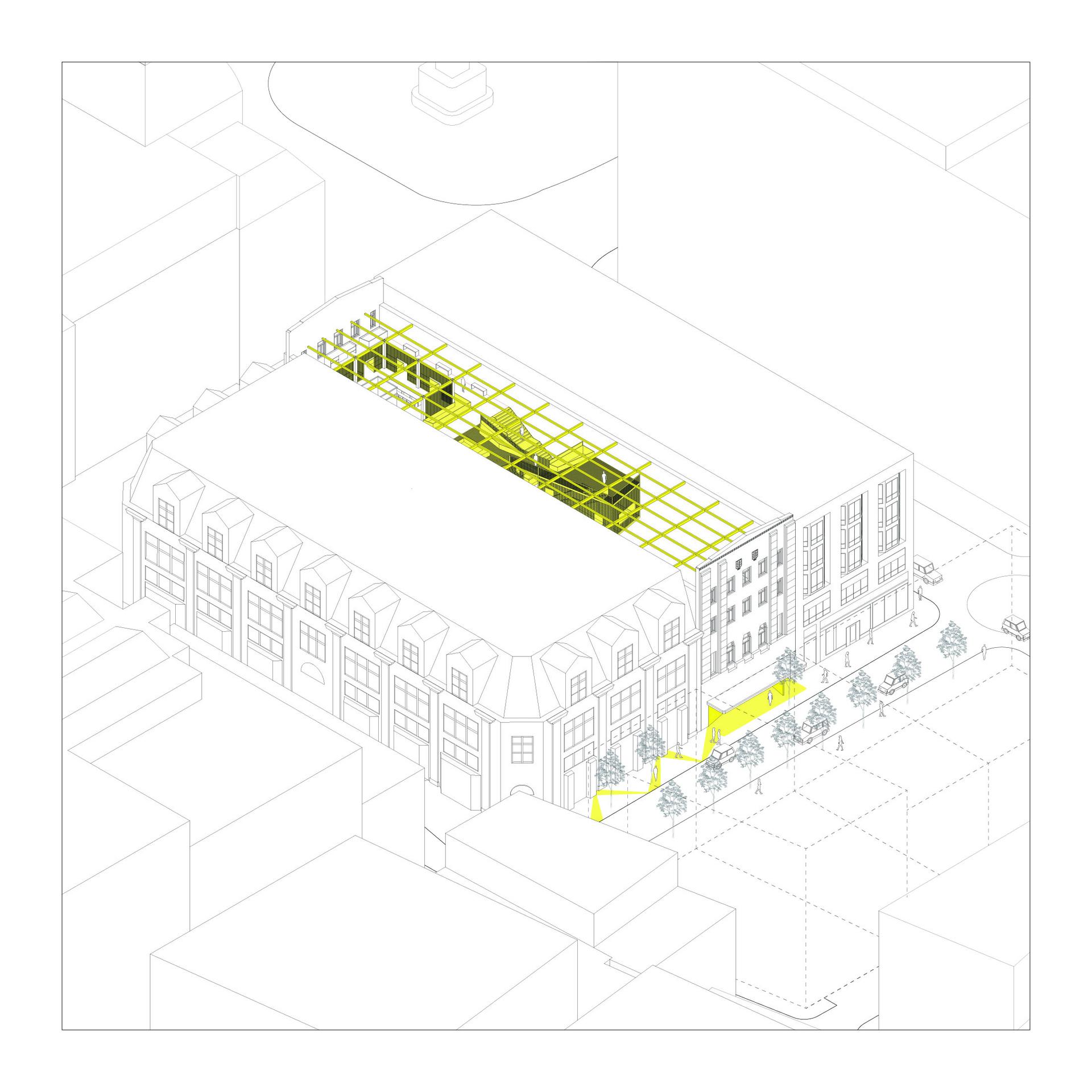

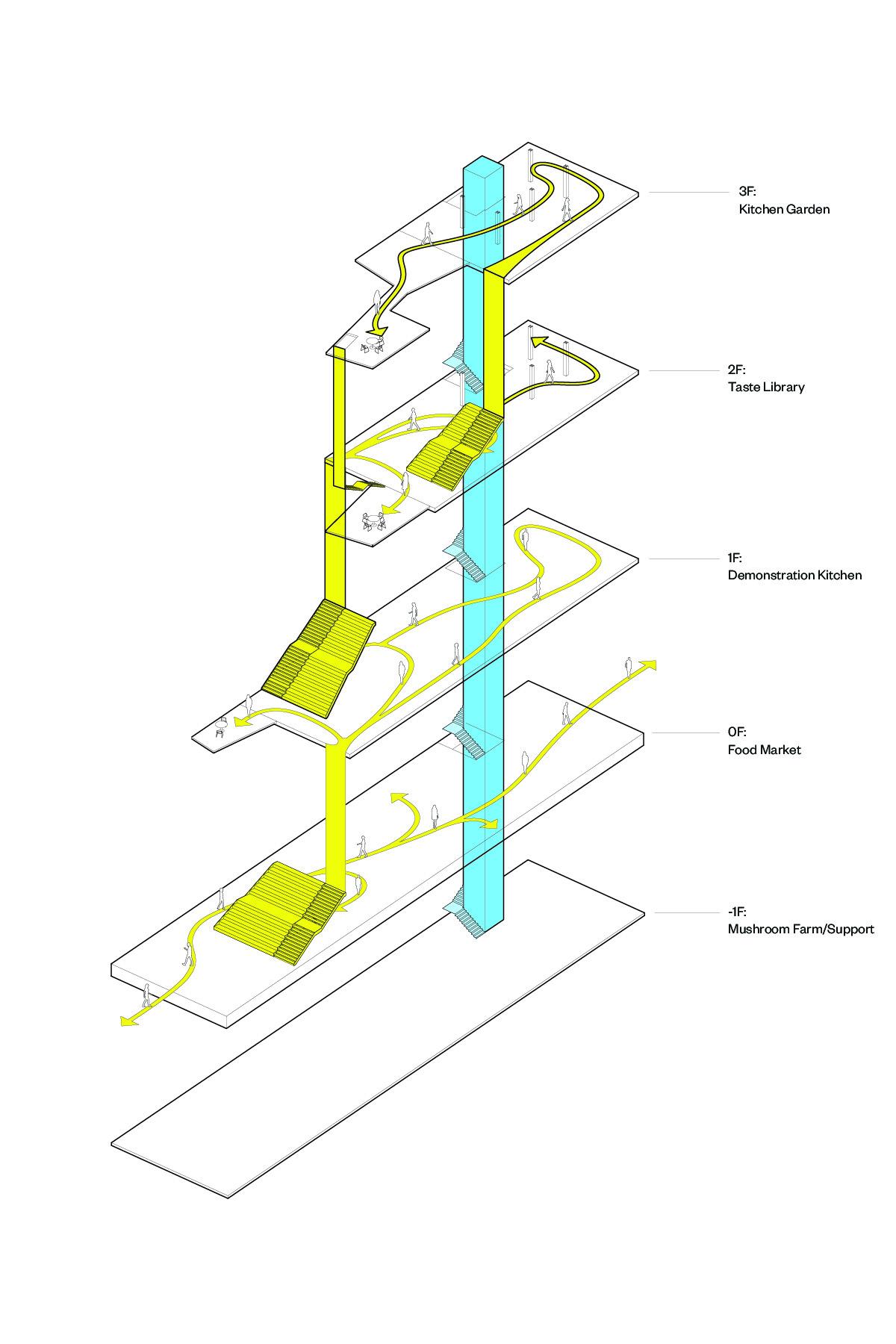

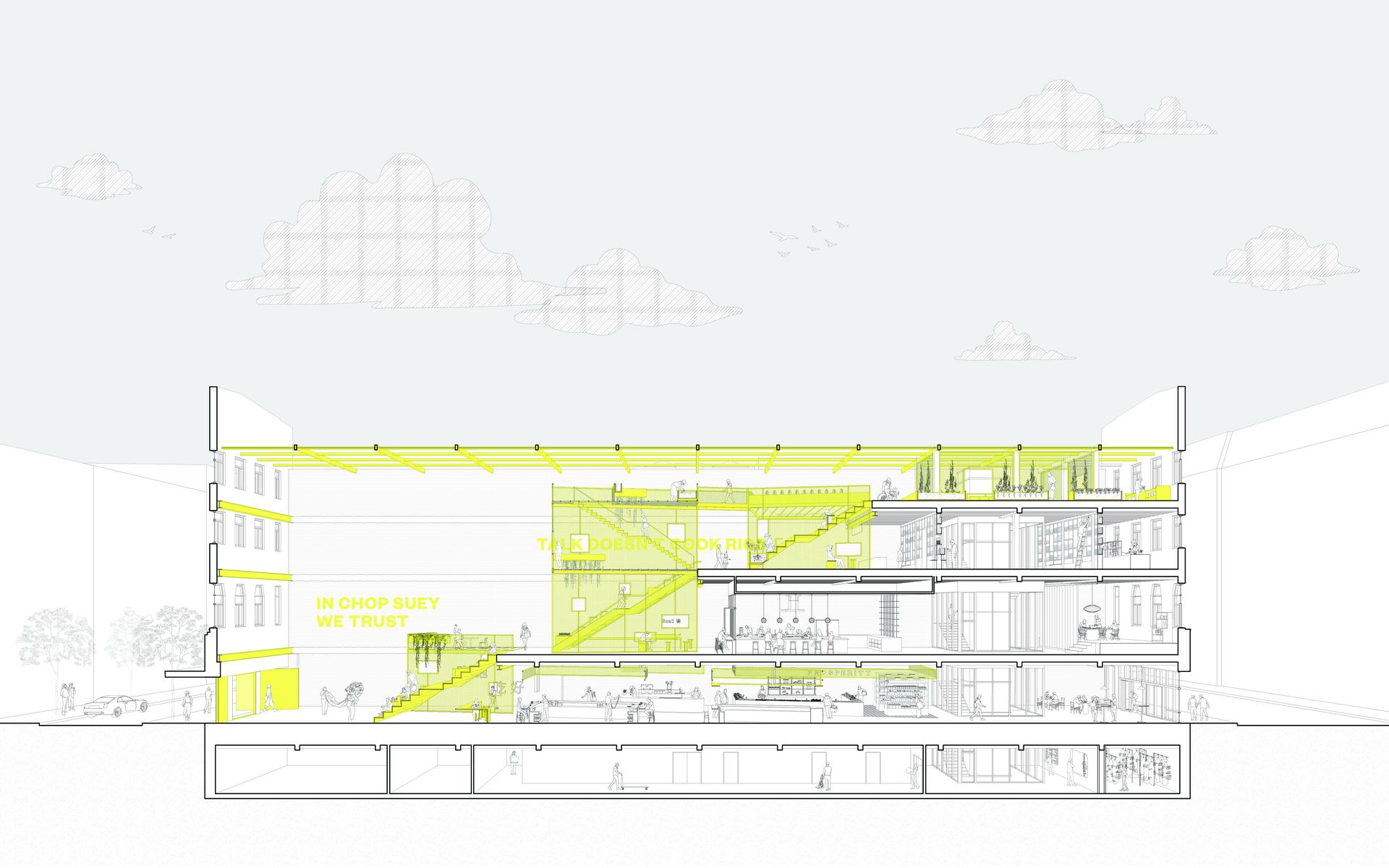

By converting the abandoned interior of the Kresge into a hub for the Chinese culinary arts, the intervention will demystify the ingredients and techniques used in Chinese cooking, while functioning as a cultural amenity for communities of all backgrounds. A vibrant social staircase cuts through the existing floor structure, establishing a bright and dynamic public atrium for visitors to enjoy. Serving multiple functions, the staircase becomes a common meeting ground where visitors can congregate, dine, and cultivate ingredients. Beyond each flight of stairs is an environment that celebrates Chinese cuisine; a food market, a demonstration kitchen, a taste lab, and a kitchen garden. Each space taps into food's potential to bring people together and allow them to understand one another. The adaptive reuse of the Kresge Building reinstates a place for cultural expression within the urban fabric of Providence that honors the memory of this forgotten Chinatown, while challenging stereotypes and shedding light on the complicated history of Chinese immigration.

Coming to America

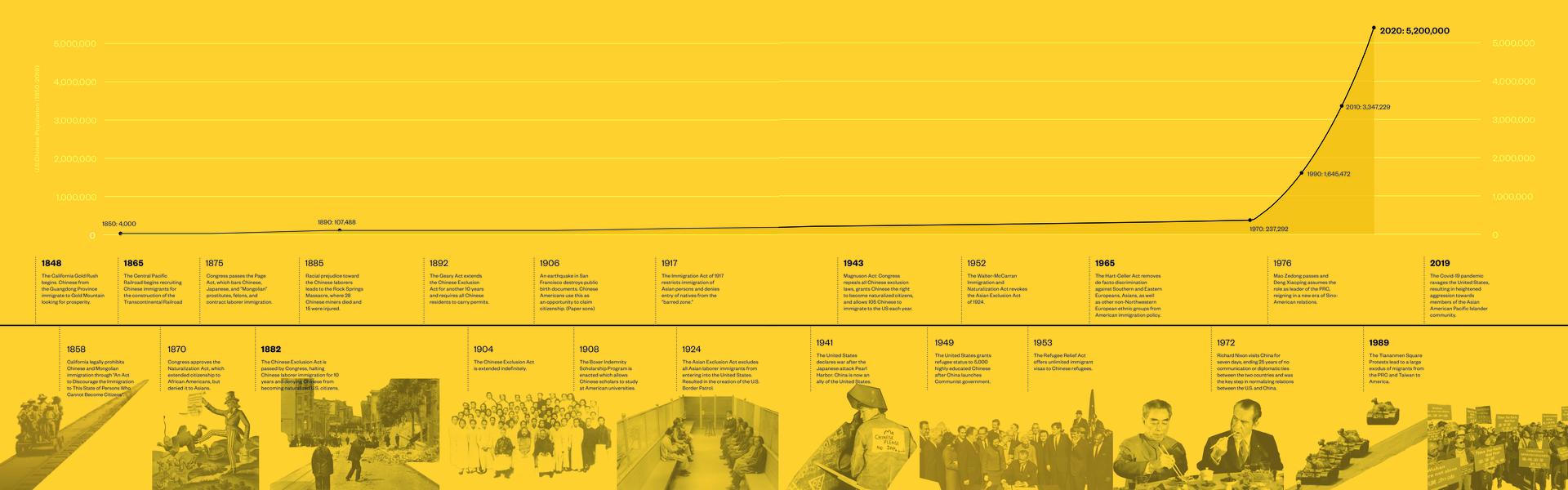

In order to understand the origins of the Chinese American restaurant industry, it is imperative to look into the deep and complicated history of the Chinese immigrant story. The first influx of Chinese immigrants occurred around 1849 during the California Gold Rush, and by 1852, it had brought over 25,000 Chinese immigrants to America, and with them, Chinese food. These early migrants were met with hostility from white America, as they were often associated with cheap labor, gambling, drugs, and as carriers of disease. Xenophobia reached a breaking point with the passing of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act which became the first ever federal law that restricted immigration based on class and barred Chinese laborers from employment.

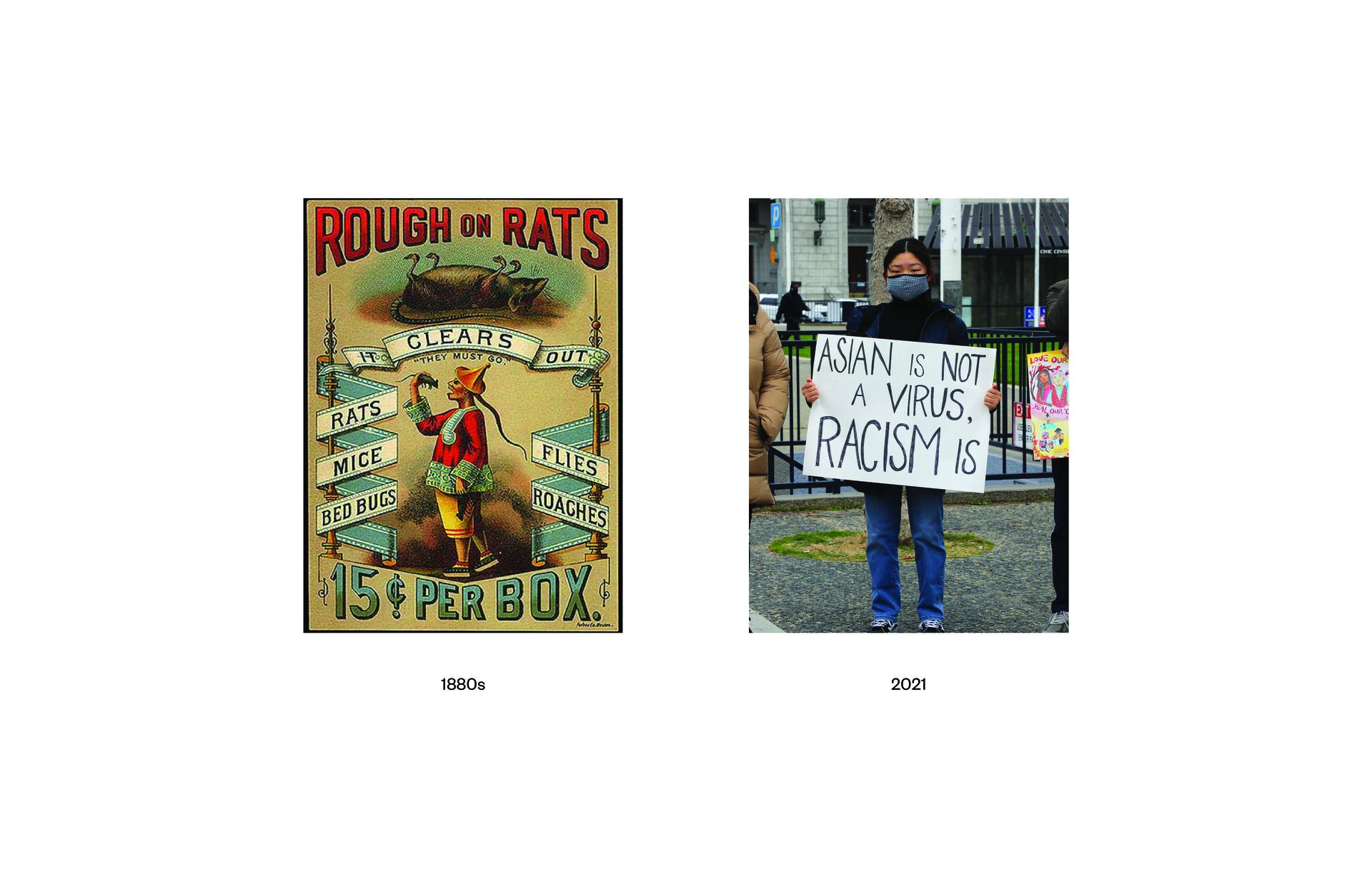

This single piece of legislation can be attributed the birth of the Chinese restaurant industry to this piece of legislation. Attitudes during this time leaned negatively towards Chinese people and their culture. As beloved as dishes such as chop suey and egg foo young became among American diners, the Chinese were perceived as an uncivilized people and attacks upon their eating habits corroborated these sentiments. Rumors were spread that the Chinese consumed “rat pies” and “vermin of the creeping crawling kind”, stereotypes that still exist today. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, fortune favored the Chinese in opposition towards Japan. As America began to open its gates to immigration, tastes for Chinese food expanded as well. Different regional cuisines were brought over from China, introducing Americans to a new world of flavors, textures, and ingredients.

Image

Today, however, these misconceptions are being revived and exacerbated in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The purported origins of the virus in a wet market located in Wuhan, China helped perpetuate the myths and fears that revolve around what Chinese people eat. Since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, researchers at Stop AAPI Hate, a coalition formed to combat racism during the pandemic, received reports of over 3,000 hate crimes against Asian, ranging from racial slurs to violent acts. America’s behavioral reaction to COVID-19 revealed that much of the ill-will and bias towards Chinese and Asian Americans still exists, and is still undeniably tied to the food we eat. In New York City alone, the NYPD recorded an over 1900% increase in anti-Asian related crimes, prompting grassroots organizations such as Send Chinatown Love and Asian restaurants across the city to pull together resources and help out these communities in need. And even with President Biden’s executive order condemning anti-Asian racism in play, the question remains, “What more can and be done to offset this hostility?”

Image

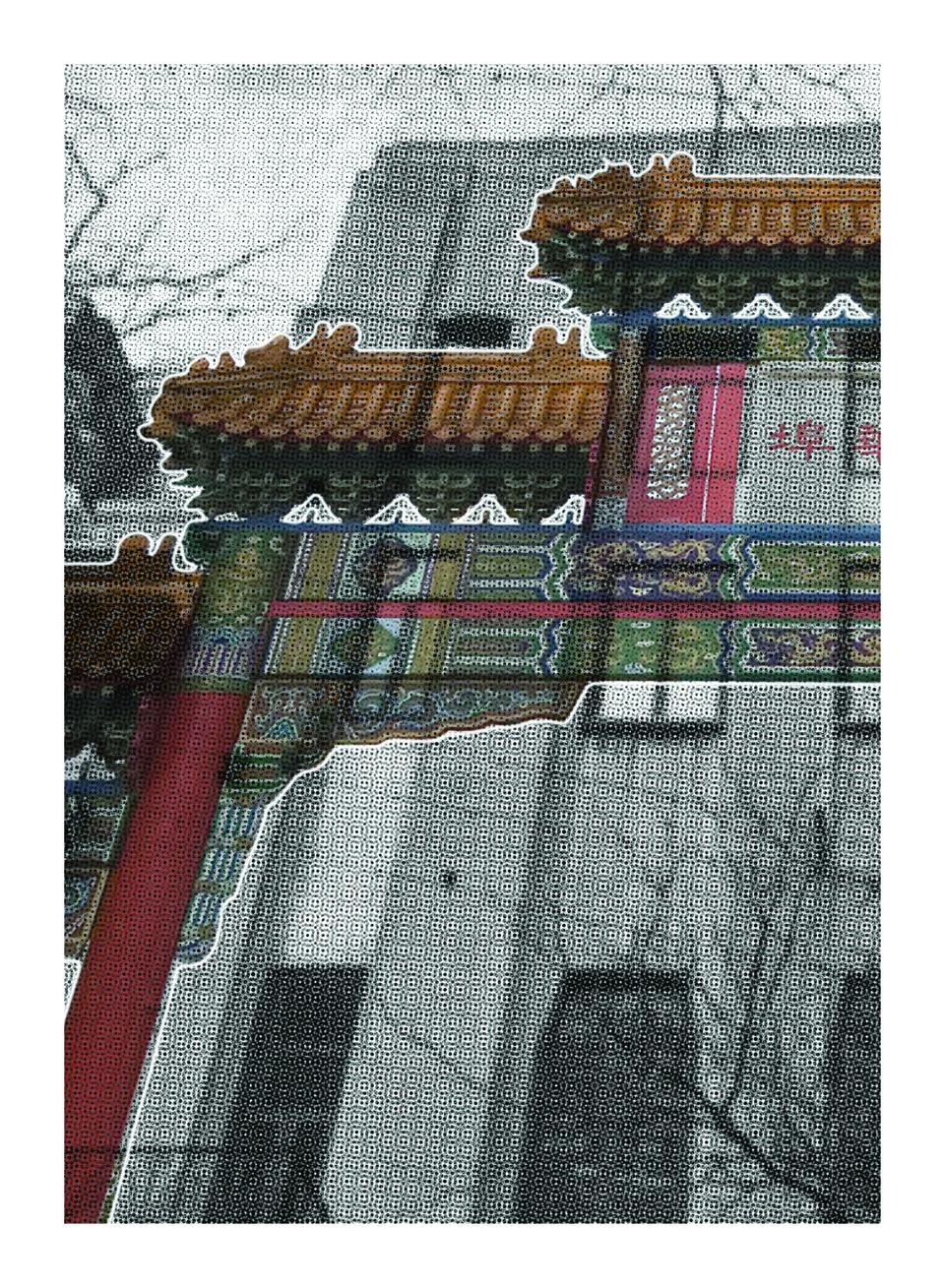

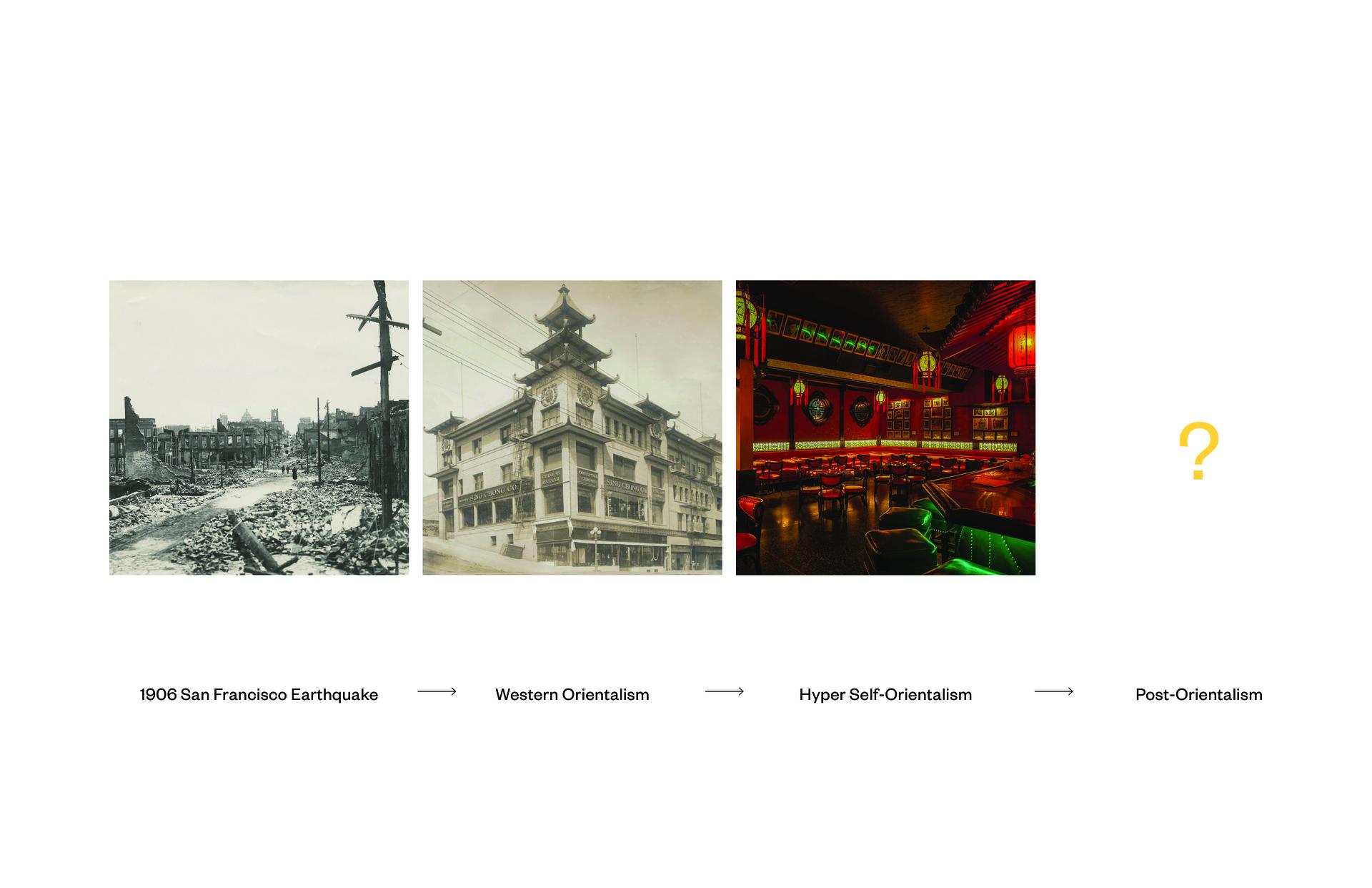

Many Americans have a shared visual impression when thinking of Chinatown: glowing red lanterns, sweeping pagoda rooftops, imposing dragon gates. The experience of visiting any Chinatown is an orchestrated experience of sights, sounds, tastes, and smells that look and feel exotic to the Western eye, but inauthentic to Chinese people. These over-exaggerated depictions of Chinese culture are products of Orientalism (Western representations of the "Orient", or non-Western civilization) and Self-Orientalism (a reflexive act of Orientalism as a means of self-preservation). This thesis intends to subvert these aesthetic expectations of Chinese culture by proposing a Post-Orientalist design approach, a new way of viewing and experiencing non-western cultures without exploiting, over-exaggerating, and or misrepresenting them.

Image

The Forgotten Chinatown

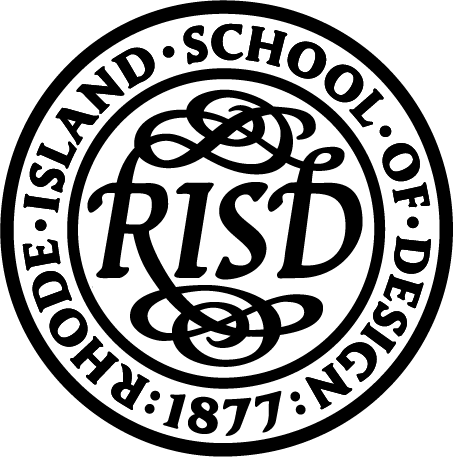

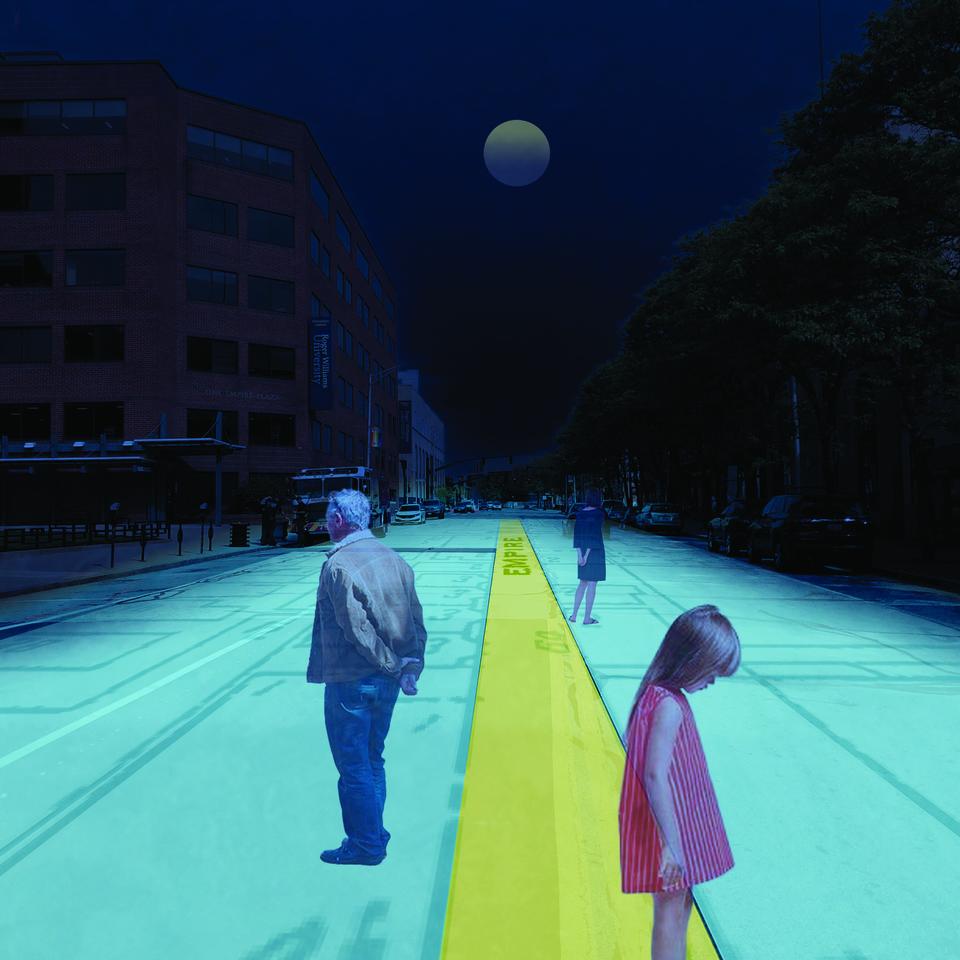

From 1900 to 1914, Downtown Providence was once home to a small, yet prominent, Chinatown. Clusters of Chinese businesses and boarding houses began to colonize the then-Burrill Street and Chapel Street, and in less than a decade, spilled into a majority of Empire Street. During this period, the number of Chinese restaurants reached its peak and made up the backbone of the Chinatown economy. Chop suey houses like the Port Arthur Restaurant and the Chin Lee Corporation became local favorites due to their relatively inexpensive menus, easily palatable offerings, and exuberant atmospheres. Unfortunately, the excitement of Providence’s Chinatown was short-lived. A call for the widening of Empire Street in 1914 resulted in the destruction of most of the buildings in Chinatown and forced many of the Chinese residents out of their homes. This sudden change in attitude and attempt at cultural erasure stemmed from the discriminatory views that many Americans harbored towards the Chinese. Chinese businesses, in particular restaurants, were seen as threats not only to the economic well-being of white-owned businesses.

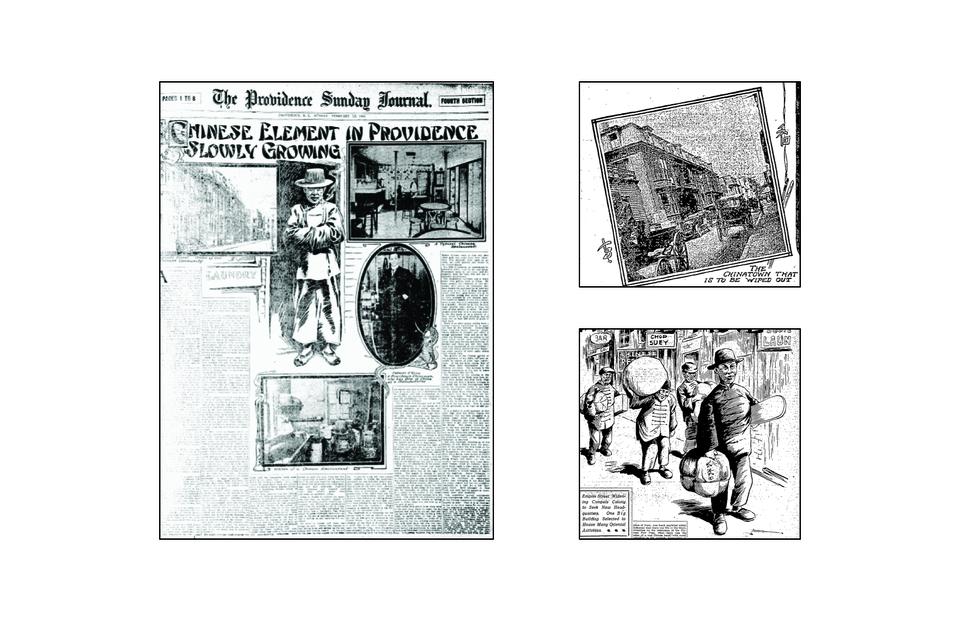

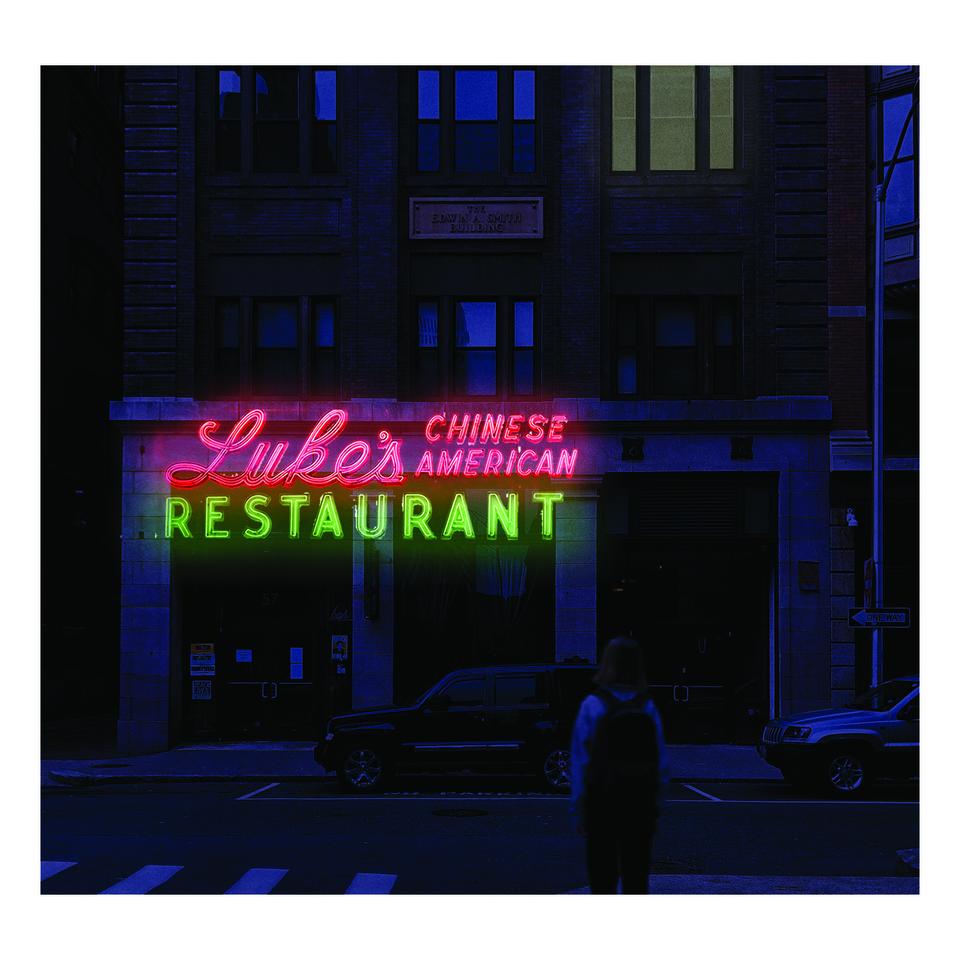

Even after the destruction of Chinatown, Downtown Providence remained home to a vibrant array of Chinese American dining establishments between the 1920s and the 1980s, as Chinese food was still popular because of its delicious flavors and inexpensive prices. Located within a few blocks from each other, these restaurants stood as testaments to the entrepreneurship and tenacity of the Chinese American community and became local favorites to those living in and outside of Providence. To residents and tourists, restaurants like the Ming Garden, Luke's Restaurant, and Mee Hong were culinary mainstays whose memories are ingrained into the cultural fabric of Providence. For the Chinese community, they functioned as a virtual Chinatown where community members could connect with one another, make a living, and establish a shared identity.

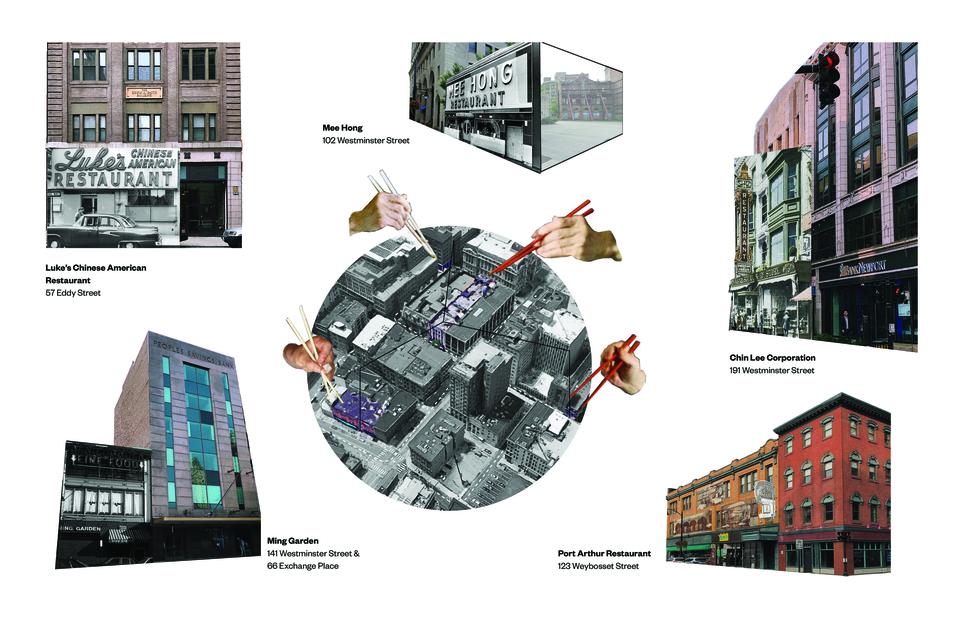

The Site: 191 Westminster Street

From 1914 to 1920, the building at 191 Westminster Street was occupied by the one of Providence’s most prominent Chinese dining establishments, the Chin Lee Corporation. Chin Lee began his life in the United States in San Francisco, working his way across the country until he settled in Providence where he opened his restaurant in 1914. The restaurant occupied the second floor of the building and was signified by its ornate and large blade signage along the building’s facade. In 1915, Lee welcomed his daughter into the world who was birthed right above the restaurant. Grace Lee Boggs would grow up to be a prominent civil rights activist during the 1960s, advocating for workers rights and working for interracial and cultural understanding.

By 1927, 191 Westminster Street was converted into the Art Deco structure that exists today. For over 40 years, the building was home to the Kresge Department store, the early predecessor to the Kmart Corporation. Designed by Kresge in-house architect James E. Sexton, it is one of the few examples of the Art Deco style in Downtown Providence. During the 1960s, Westminster Street was transformed into a pedestrian mall in an effort to revitalize Downtown and attract more shoppers. Despite this attempt, the project ultimately failed, and retail stores like the Kresge Department Store went out of business. Today, the Kresge Building is currently unoccupied.

Image

With this thesis, I ask, "Do Chinese American restaurants and culture still need to look and feel "Chinese" in order to find success? In turn, my design seeks a Post-Orientalist approach towards creating a new perception of Chinese culture and cuisine.

The intervention will occur on both an architectural and urban scale, breathing new life into Downtown Providence that embraces and celebrates Chinese culture through food and memory, rather than with an imagined, overexaggerated Orientalist aesthetic.

A Network of Ephemeral Memories

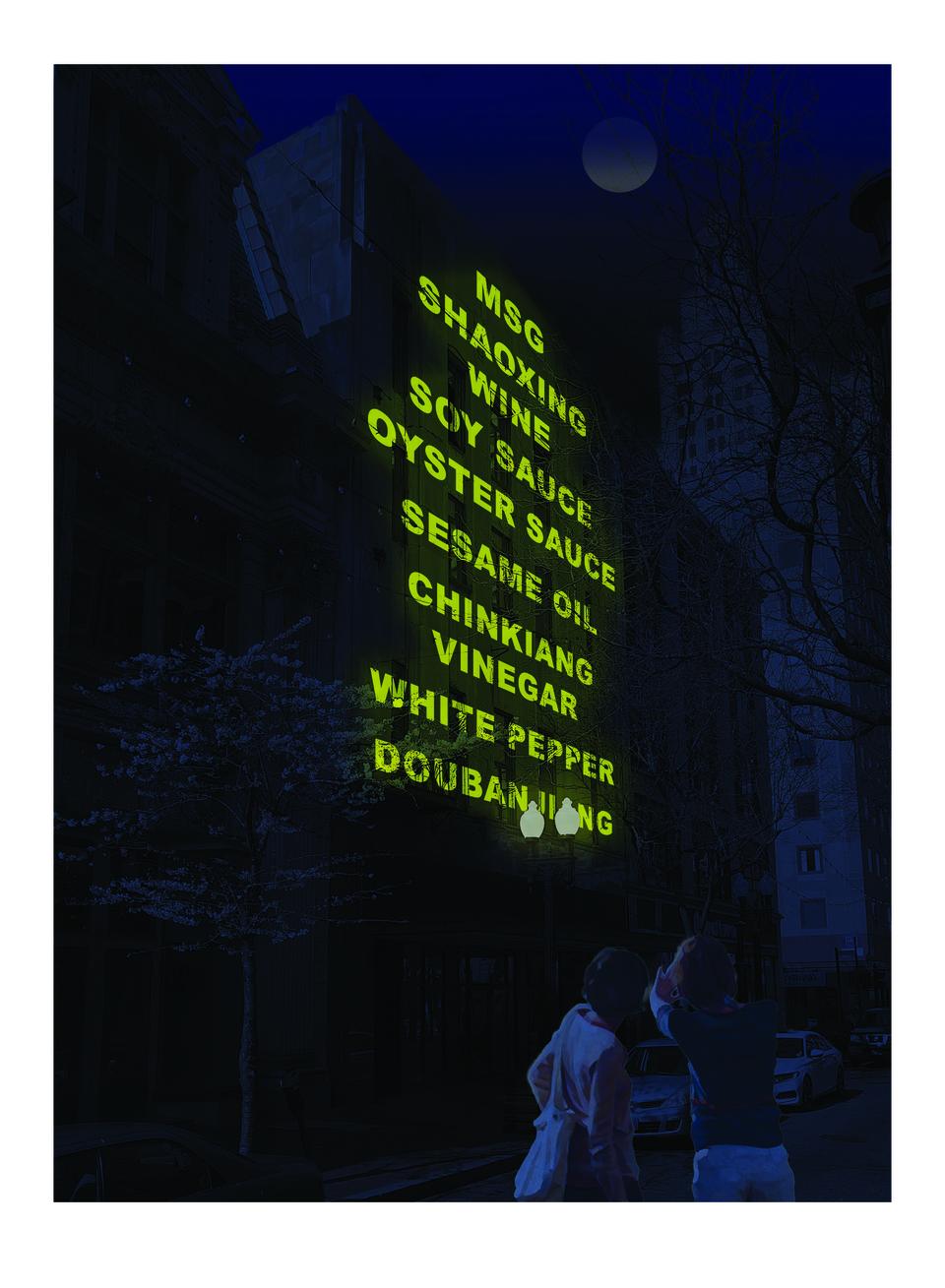

To bring recognition to Providence's lost Chinatown, the intervention first occurs on an urban scale. With so many bygone Chinese restaurants within walking distance of each other in downtown Providence, there is an opportunity to reactivate their memory for the public to see. Through the medium of digital projection, a curated collection of provocative, non-permanent images will create a network of ephemeral memories that will illuminate downtown and bring awareness to this forgotten community.

Image

The digital interventions culminate with the host site, the Kresge Building. To preserve its Art Deco nature, a dynamic facade of rotating digital projections transforms the building into a landmark in Downtown Providence. An exhibit of Providence's Chinatown and of Chinese American history and culture will light up the building's facade, telling a different narrative each night. The illuminations signify that the Kresge Building is a portal into a new world, functioning like the iconic gateways found throughout American Chinatowns.

A Culinary Playground

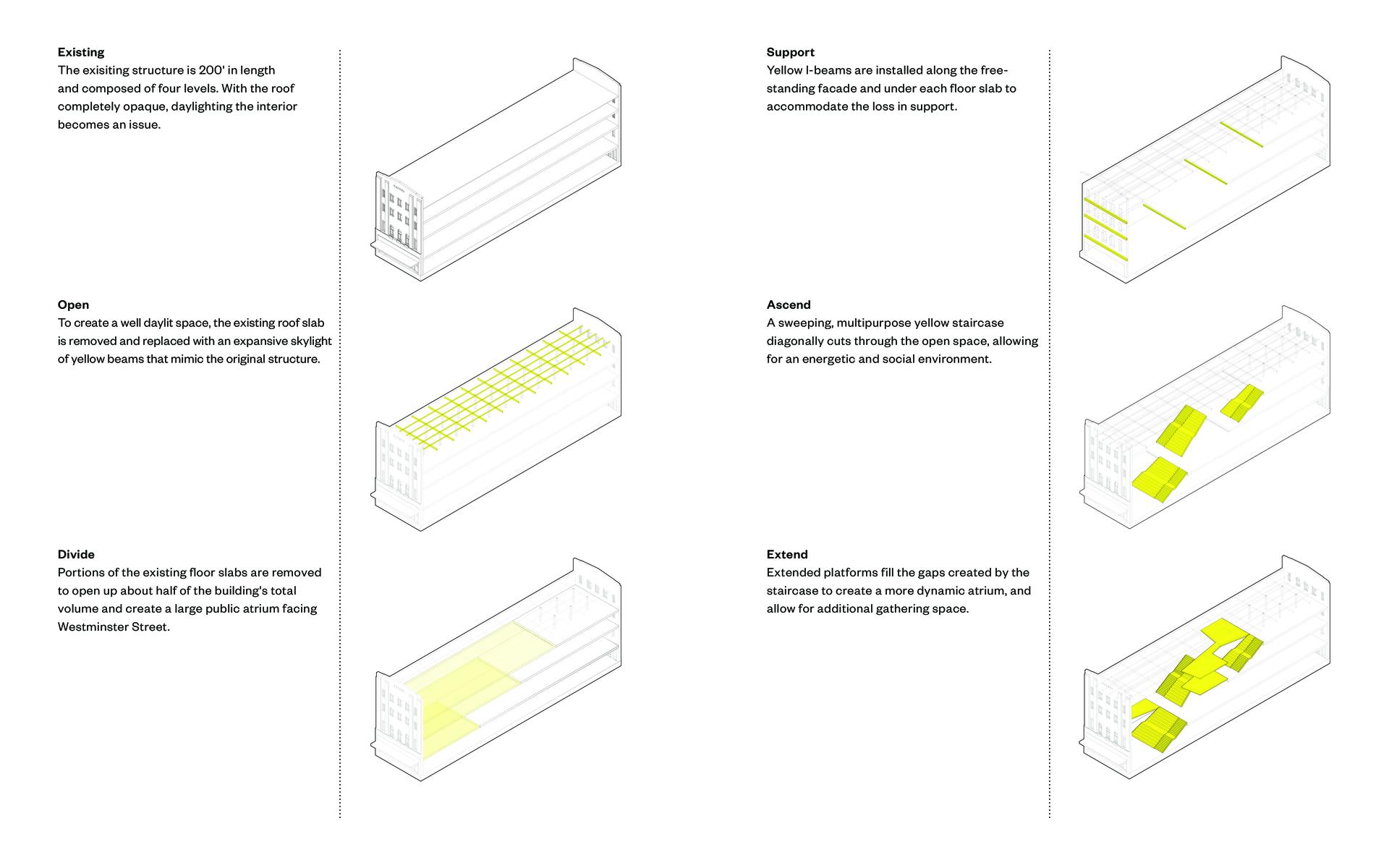

As a response to the erasure of Providence's Chinatown and its rich community, the initial action of the intervention is to bisect the building. The floors of the Kresge Building will be diagonally sliced in half, in both section and in plan. This gesture is not only symbolic of erasure, but it also allows the building to become a more open and public environment.

Image

Image

Image

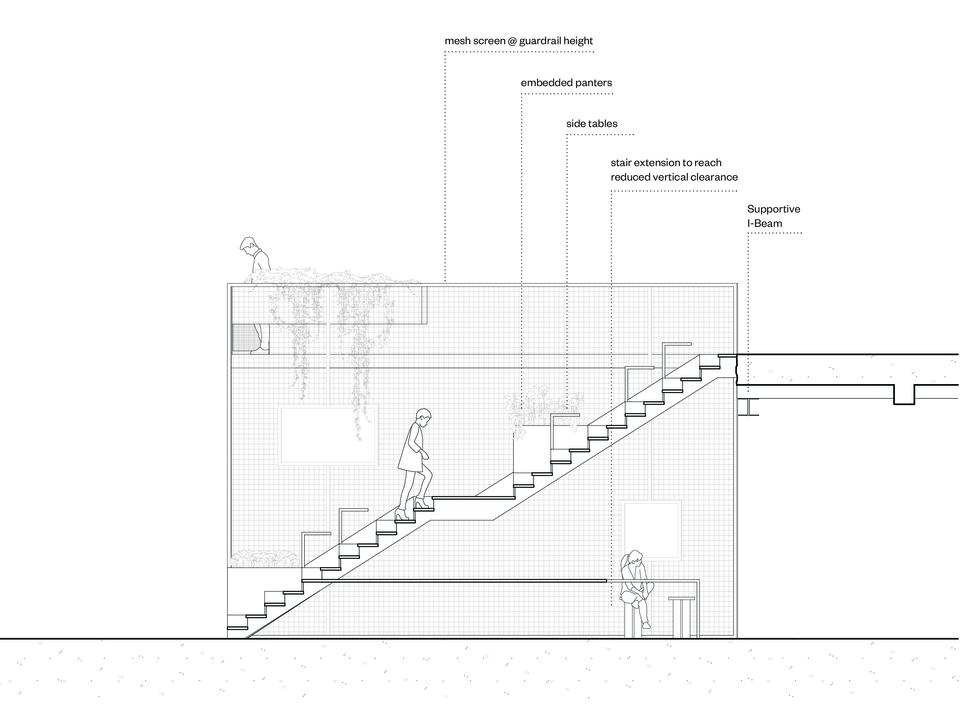

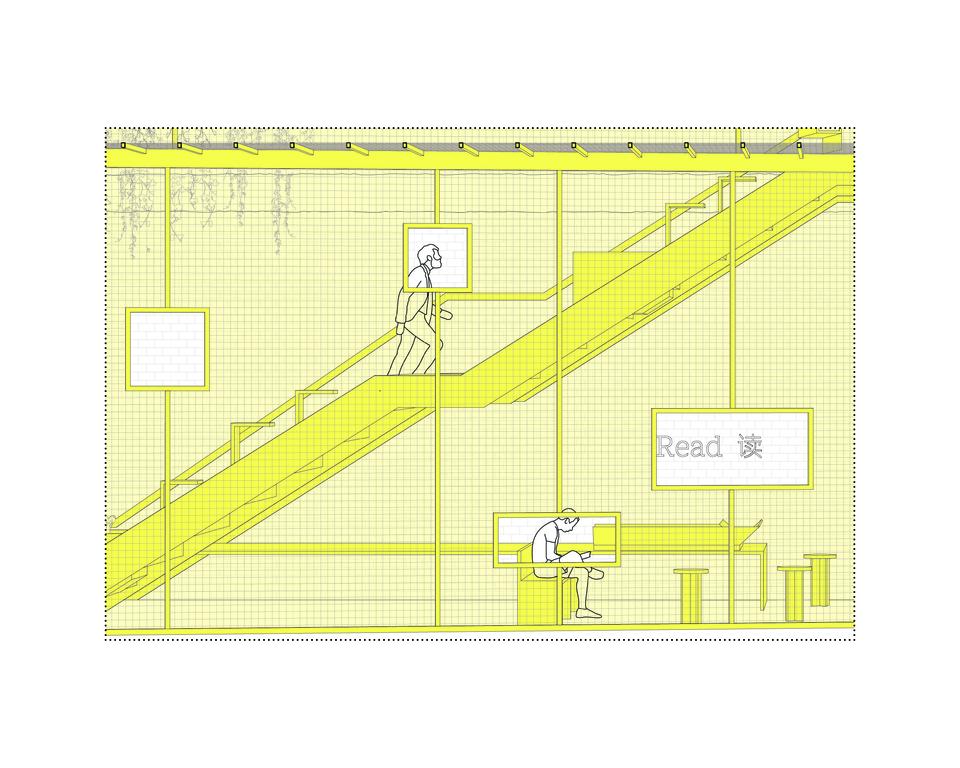

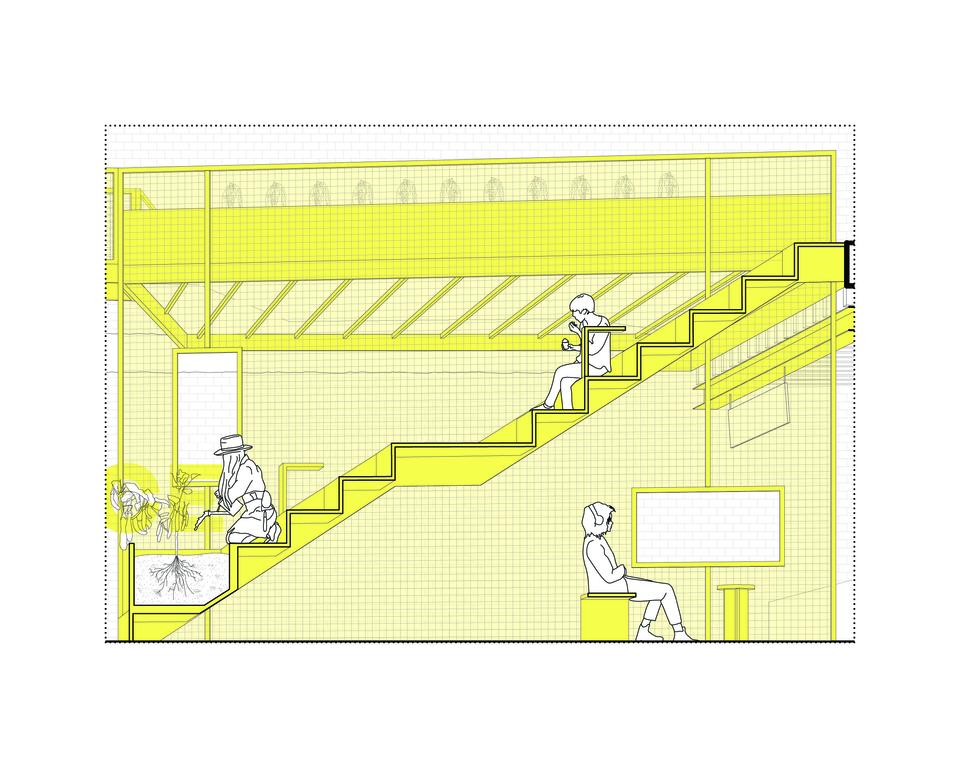

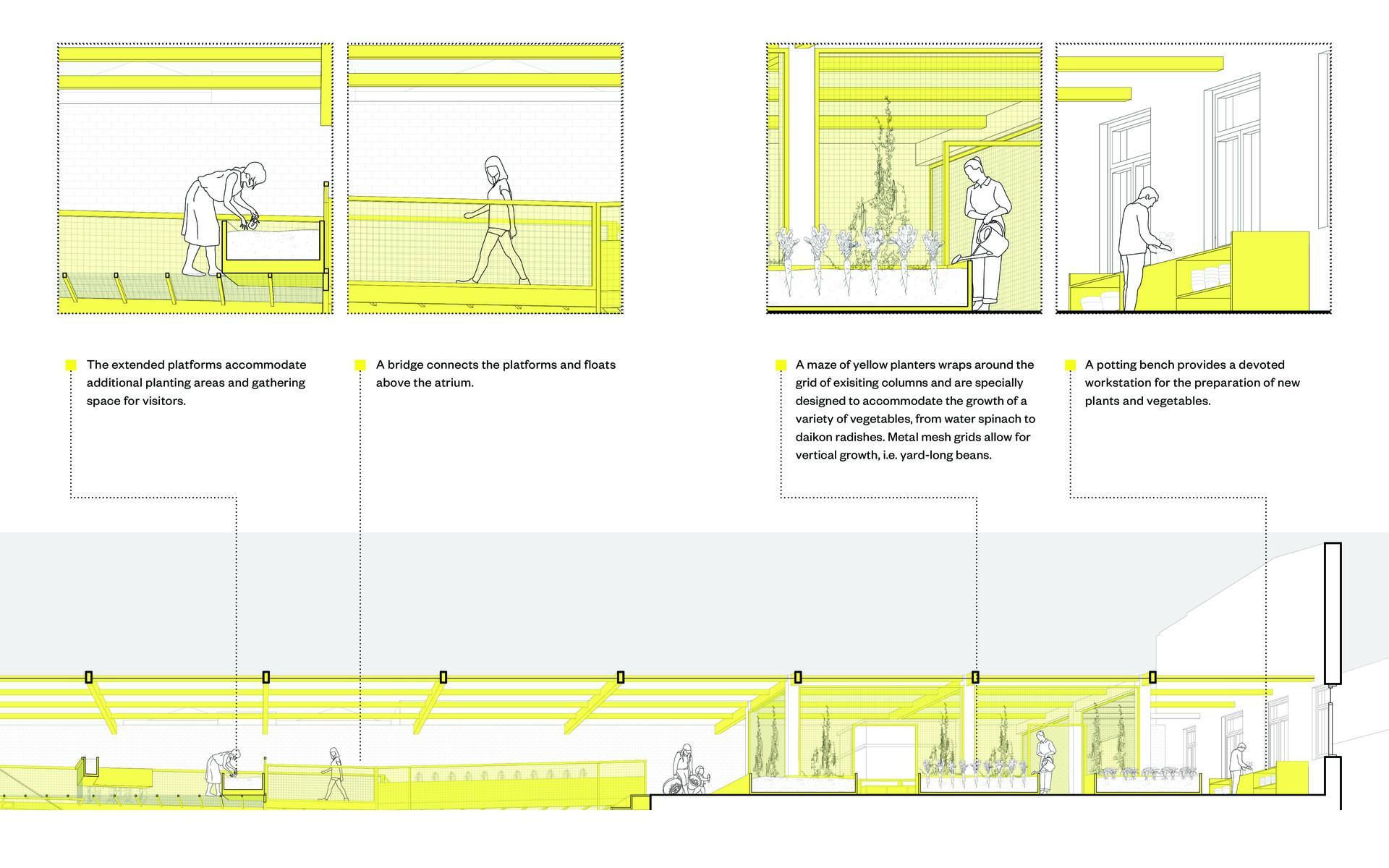

▲ The staircase is composed of functional units that allow for a communal and interactive experience. Ascending visitors are given a space to repose, eat a meal, or cultivate vegetables.

The resulting "culinary playground" will accommodate a multitude of ways to experience the new programming. The addition of a new vertical core offers a top-down, ADA accessible culinary experience where visitors learn about Chinese cuisine starting with the ingredients and ending with the plate.

The yellow staircase results in a journey of discovery, offering a more liberating path. Visitors are naturally drawn up by the sweeping staircase, but are given moments of assembly, enlightenment, and rest. The staircase, therefore, functions as a supplement to the culinary programming on each floor. Regardless of the path taken, visitors are transported to an entirely different environment on each floor that introduces them to world of tastes, sights, sounds, and smells.

Visitors who are in a hurry can also use the ground floor as a thoroughfare between Westminster Street and Fulton Street, picking up a snack from the market.

Image

Image

As fresh Chinese produce is hard to come across in Providence, a community operated kitchen garden devoted to Chinese vegetables is located on the third floor. Visitors will learn about Chinese produce and its cultivation, and eventually harvest the vegetables to be used in the demonstration kitchen, for a true garden-to-table experience. The bright environment brings together community and invites moments of collaboration and repose.

Image

Image

Image

▲ A communal table provides a rooftop dining experience and can be used for casual gatherings, banquets, and demonstrations.

Image

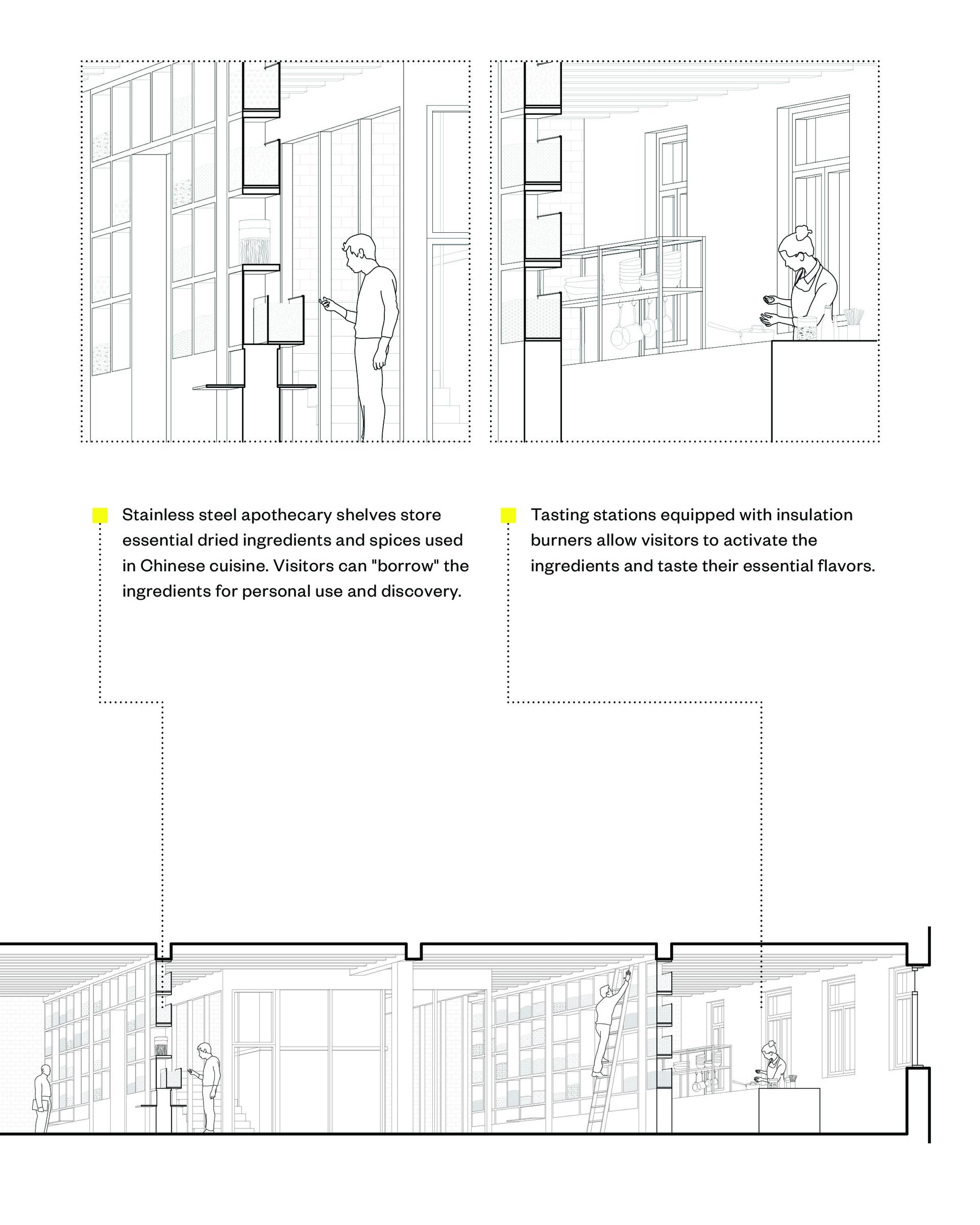

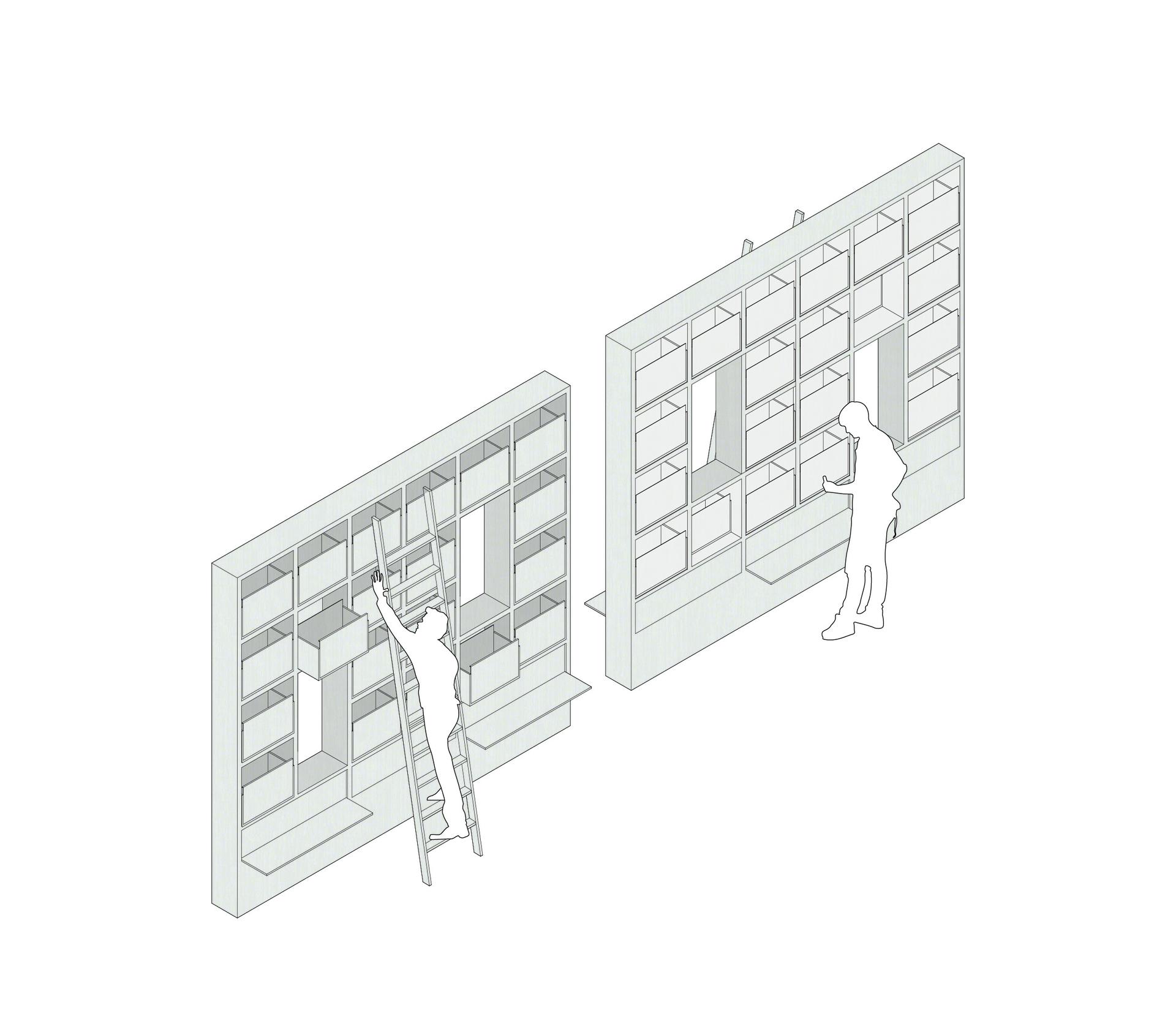

On the second floor, the visitor is welcomed by a colorful and aromatic world of spices, herbs, and dried ingredients. The Taste Library is a contemporary interpretation of a typical Chinese apothecary; stainless steel shelves house a variety of ingredients and create a sense of enclosure. The open nature of the shelves allows the ingredients to be placed on display and a symphony of fragrances to waft through the space. Here, visitors learn about the building blocks of Chinese cuisine and its many flavors.

Image

Image

▲ The stainless steel shelves act as wall partitions and exhibit varying levels of transparency. Shelves have glass backs that create a display of colorful ingredients. Larger openings can be used to store larger containers and wet ingredients.

Image

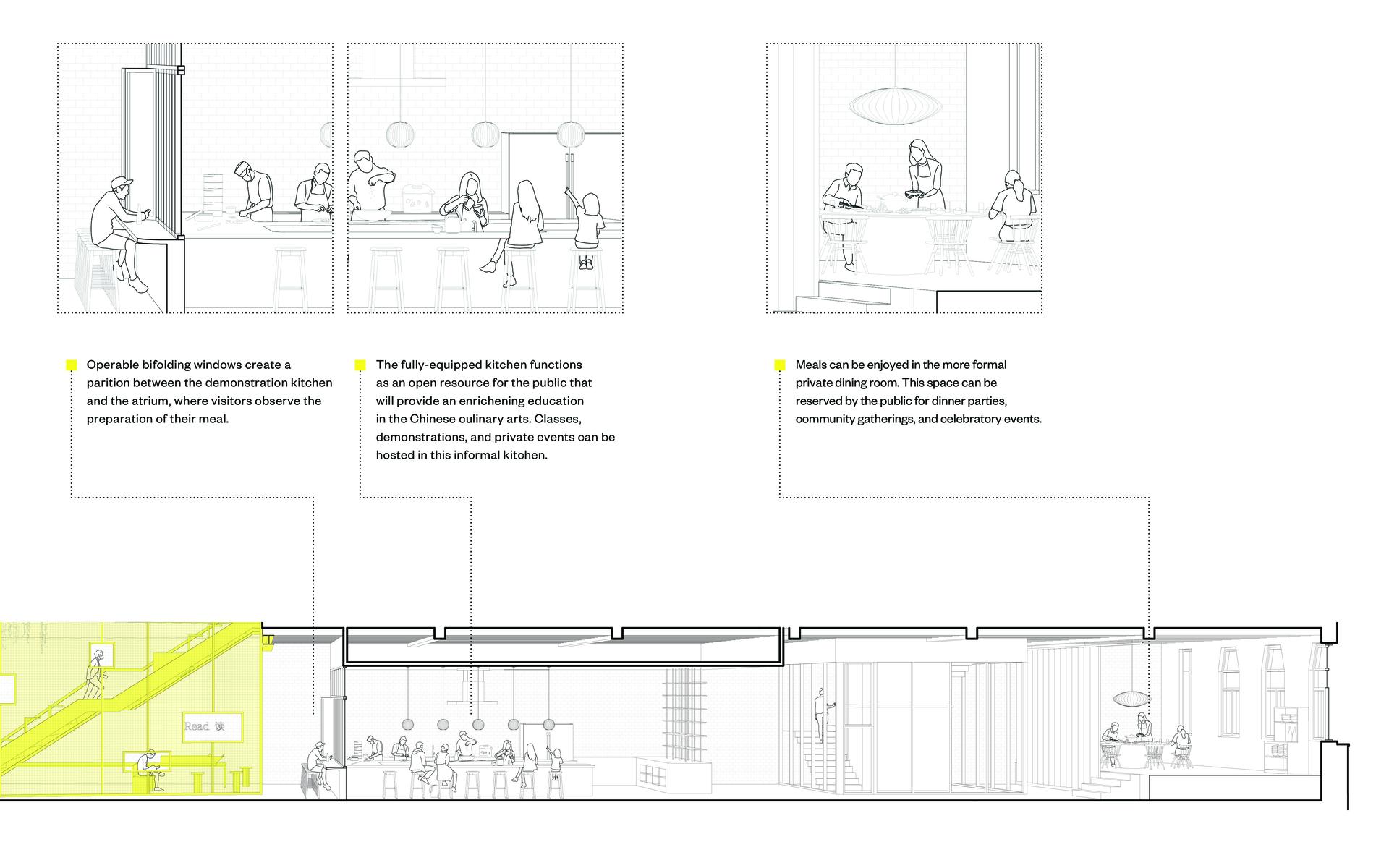

The demonstration kitchen located on the first floor is where visitors can apply their newfound knowledge of Chinese ingredients to the wok. Classes taught by resident chefs or students from Johnson and Wales will demonstrate the wide range of cooking techniques unique to Chinese cuisine. Budding local chefs can also rent the kitchen to host meals for the community to help kickstart their culinary careers. The arrangement of the kitchen allows for ample space for chefs to move about safely and efficiently, while placing the spectacle of cooking on display for the viewer. Visitors can discover and test classic Chinese recipes and enjoy the experience of a homecooked Chinese feast with friends and family in a more intimate dining room setting.

Image

Image

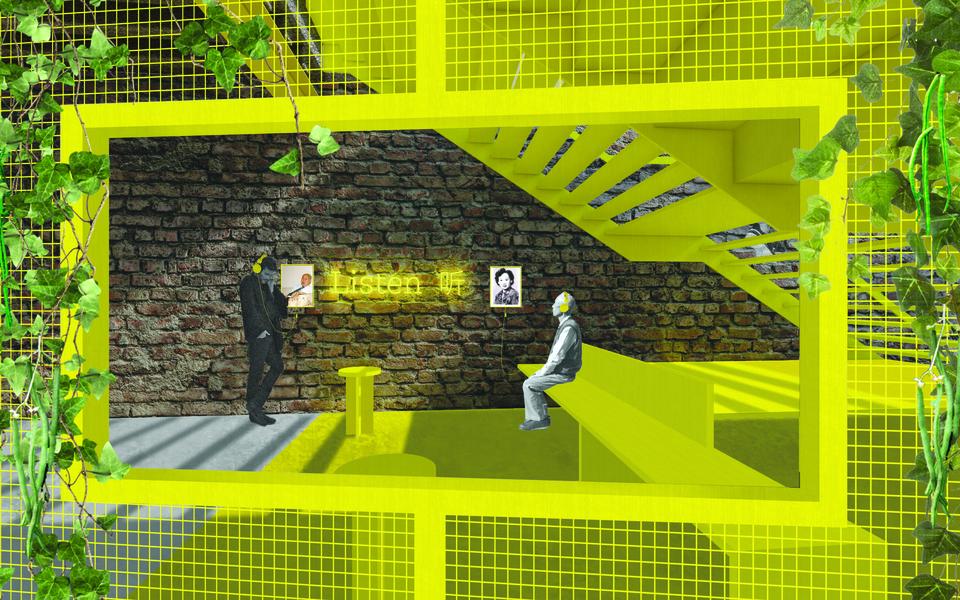

Underneath each flight of stairs are curatorial moments that shed light on Providence's past. A reading room on the first floor contains archival photographs and newspaper articles documenting the physical presence of Providence's Chinatown and its restaurants. On the second floor, visitors can listen to oral histories of Chinese residents, past and present, and their recollections of this once vibrant community. These intimate spaces serve as reminders and mementos of a forgotten community whose presence today would have no doubt greatly contributed to the vitality of downtown Providence.

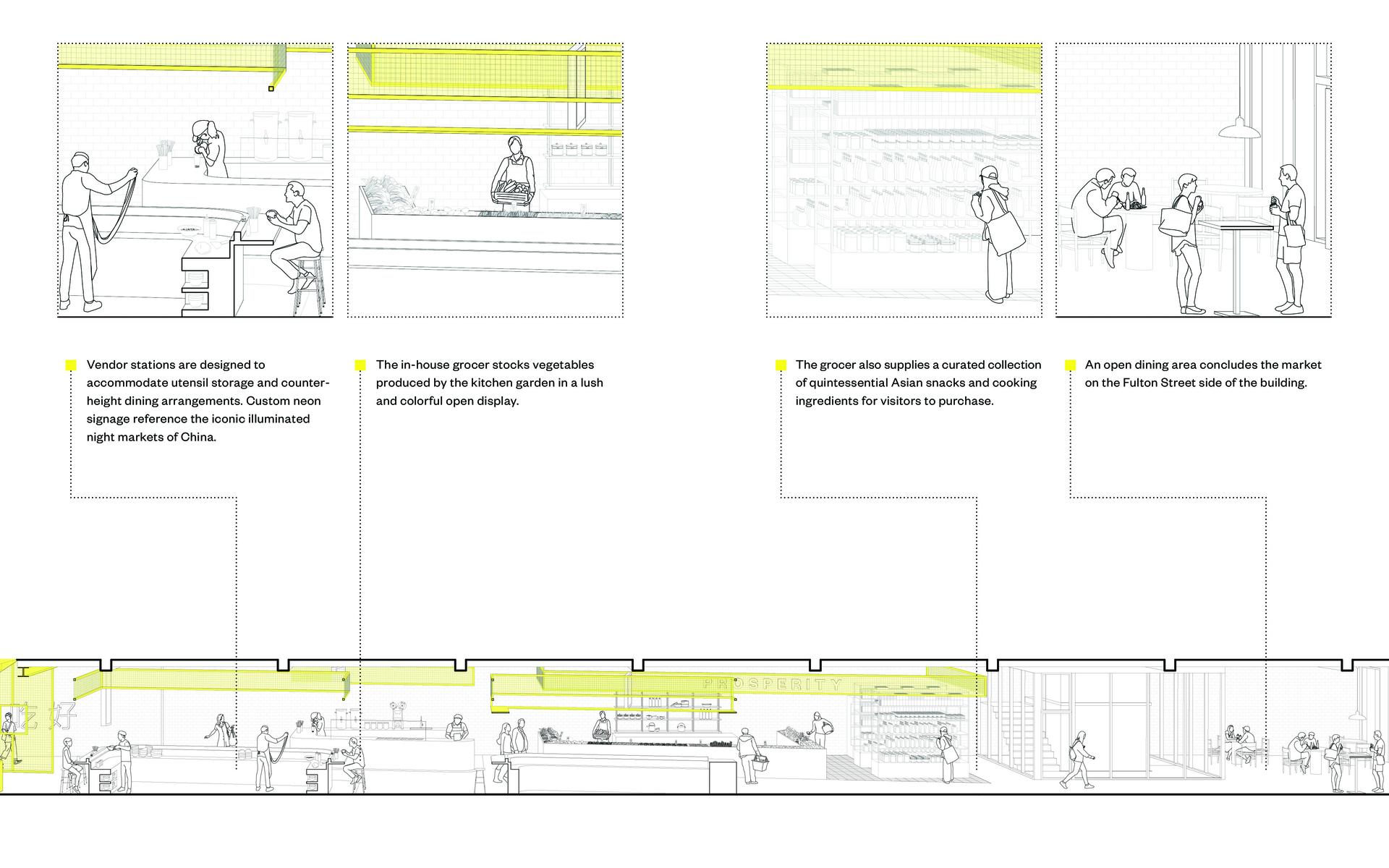

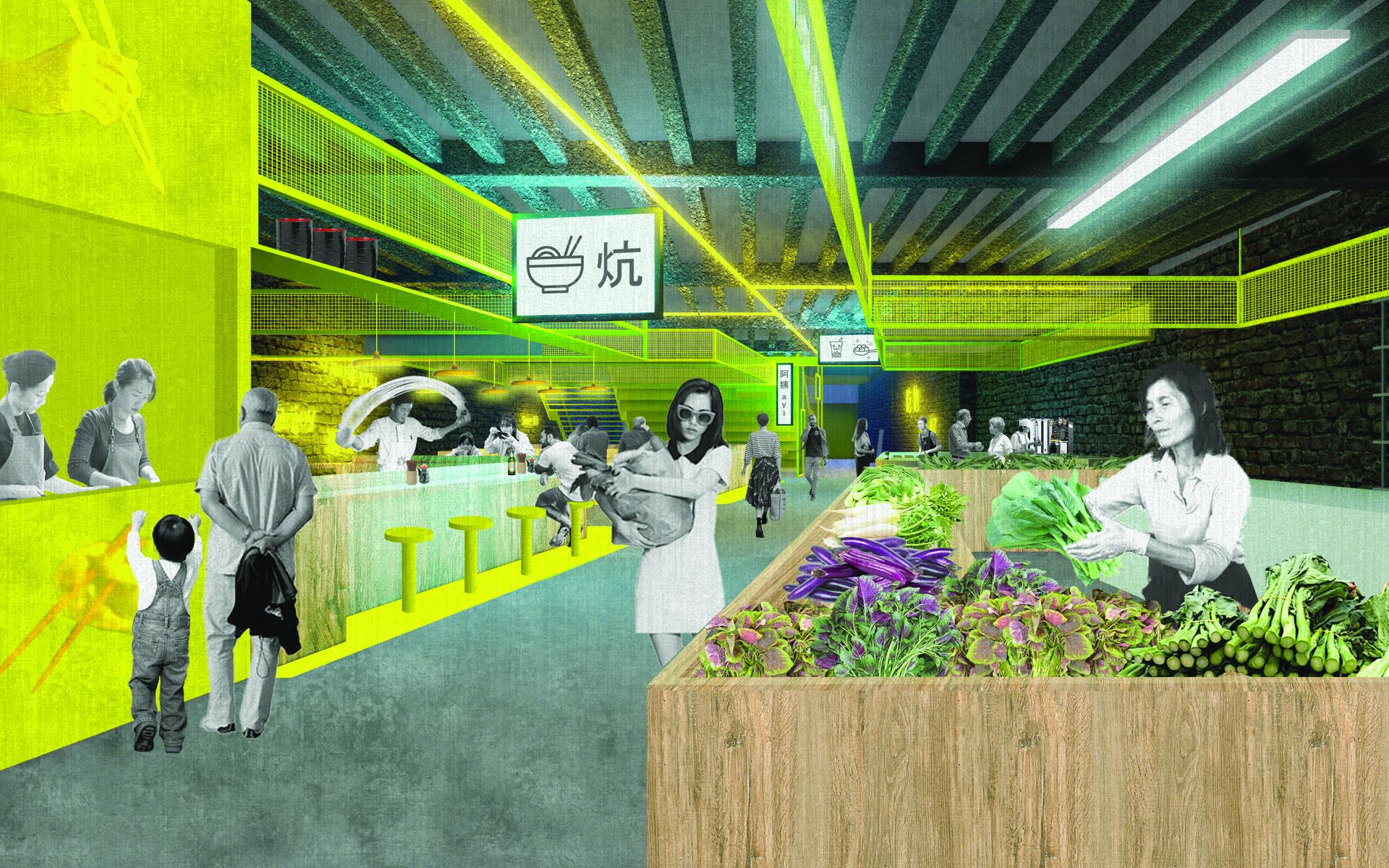

Once visitors have had a chance to experience cooking Chinese food themselves, they can further satiate their appetites on the ground floor. The culmination of the culinary journey, the indoor food market focuses on Chinese street food and will serve a variety of regional delicacies. From hand pulled noodles to bubble tea, the market is a celebration of the diversity of Chinese cuisine. Neon lights and open kitchens bring an energy to the space that is reminiscent of iconic Chinese night markets.

Vendor stations surround an avenue that follows the same angle of the atrium staircase. Each station is equipped with standard kitchen equipment but can be customized by the vendor to fit their needs and identity. Diners have ample seating options, or can enjoy their meals on the stairs of the public atrium.

Image

Image

Food is a common language between humans. We all need it to survive, and we enjoy consuming it. Food has the ability to bring people together and allow us to understand each other. It serves as a portal into other cultures, revealing flavors, spices, ingredients, and textures different from what we are accustomed to.

Unfortunately, food can also be misunderstood. Much of the adversity Chinese Americans have endured stems from misconceptions and stereotypes of our cuisine, even though it remains one of the most popular cultural foods among Americans. And in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, these misconceptions are finding new light and being further exacerbated.

The Chinese American story is, at once, both rich and complicated. While our presence in this country is most widely accepted today, the path towards this acceptance was frought. For almost 200 years, Chinese immigrants have strived to live a life apart from their homeland and achieve the “American dream”. And for many, making food for others became their way of life, as well as a way of survival.

This intervention sheds the aesthetic expectations associated with Orientalism. It offers a new lens with which to see and experience Chinese culture, one that is immersive, didactic, and joyful rather than explotative, misinformed, and over-exaggerated. My intent is to introduce a new type of environment where Chinese food can be celebrated together as a community, while also learning about the intricate histories that have kept it alive in America. This fusion of food, identity, and memory will create a new cultural destination in the heart of downtown Providence.

I hope this thesis has been successful in giving a voice to the narratives that are unknown and seldom recounted.

Image

ANNONTATED BIBILOGRAPHY

- Alcorn, Chauncey. April 20, 2020. “Coronavirus’ Toll on Chinese Restaurants Is Devastating.” CNN. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/21/business/coronavirus-chinese-restaurants….

- Chin, Gabriel J., and John Ormonde. 2018. “The War Against Chinese Restaurants.” Duke Law Journal 67 (4): 681–741.

- “Chinese Restaurants of the Past.” n.d. ArtInRuins. Accessed December 15, 2020. http://artinruins.com/property/chinese-restaurants/.

- Chong, Raymond Douglas, Tanfer Emin-Tunc, Bruce Makoto Arnold, and Project Muse, eds. 2018. Chop Suey and Sushi from Sea to Shining Sea: Chinese and Japanese Restaurants in the United States. Food and Foodways Series. Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press.

- “Coronavirus Fears Are Reviving Racist Ideas About Chinese Food.” n.d. Accessed November 17, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en/article/4ag37q/coronavirus-fears-are-reviving-r….

- Davis, Charles. October 14, 2020.“UN Report: Trump ‘seemingly Legitimizing’ Hate Crimes against Asian Americans - Business Insider.” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/un-report-trump-seemingly-legitimizing-….

- Feng, Angela and Fontana, Juliana. 2018. Providence’s Chinatown Exhibition. Brown University.

- Hong, Cathy Park. 2020. “The Slur I Never Expected to Hear in 2020.” The New York Times, April 12, 2020, sec. Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/12/magazine/asian-american-discriminati….

- Lim, Imogene, and John Eng-Wong. 1994. “Chow Mein Sandwiches: Chinese American Entrepreneurship in Rhode Island.” In Origins and Destinations: 41 Essays on Chinese America, 417–36. Los Angeles: Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

- Liu, Haiming. 2009. “Chop Suey as Imagined Authentic Chinese Food: The Culinary Identity of Chinese Restaurants in the United States.” Journal of Transnational American Studies 1 (1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2bc4k55r#page-1.

- Mendelson, Anne. 2016. Chow Chop Suey : Food and the Chinese American Journey. Arts and Traditions of the Table: Perspectives on Culinary History. New York: Columbia University Press. http://0-search.ebscohost.com.librarycat.risd.edu/login.aspx?direct=tru….

- Stone, David Norton. 2019. Lost Restaurants of Providence. Arcadia Publishing.

- Tansey, Tilli. 2019. “Plague in San Francisco: Rats, Racism and Reform.” Nature 568 (7753): 454–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01239-x.

- Yan, Grace, and Carla Almeida Santos. 2009. “‘CHINA, FOREVER’: Tourism Discourse and Self-Orientalism.” Annals of Tourism Research 36 (2): 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.01.003.

- Zhang, Jenny G. 2020. “Coronavirus Panic Buys Into Racist Ideas About How Chinese People Eat.” Eater. January 31, 2020. https://www.eater.com/2020/1/31/21117076/coronavirus-incites-racism-aga….