How We Can Modify the Home for People with Dementia

ABSTRACT

More than 50 million people live with dementia worldwide. For reasons of familiarity, affordability, and psychological comfort, the home is uniquely preferred by people with dementia (PwD) and their caregivers for aging in place. Ample studies show that built environmental features (e.g., furnishing, lighting, layout) influence the daily lives of PwD. These features can be modified easily and with fewer disruptions to daily life at home. However, most PwD and their caregivers usually have little knowledge of what can be achieved through simple interventions to environmental features.

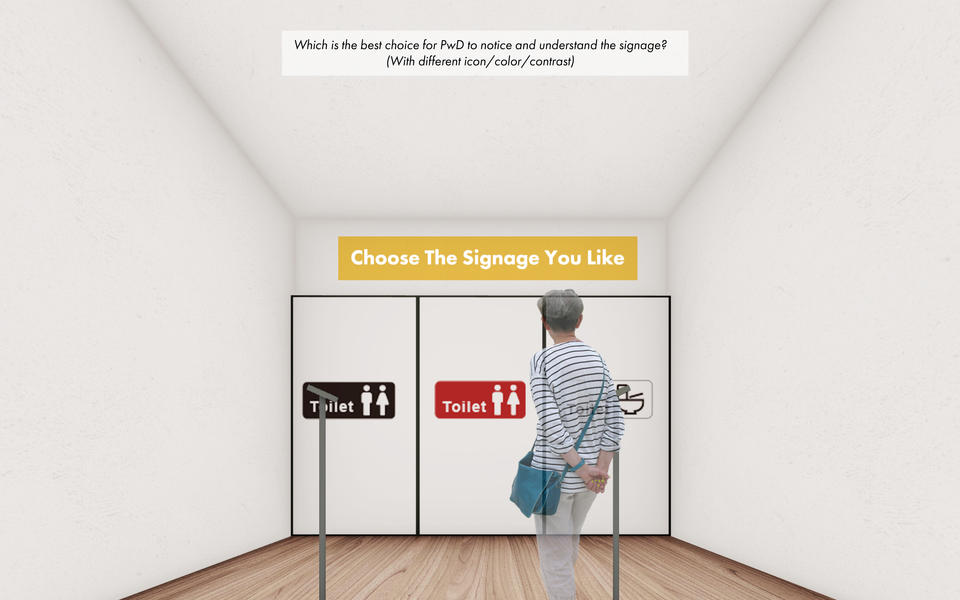

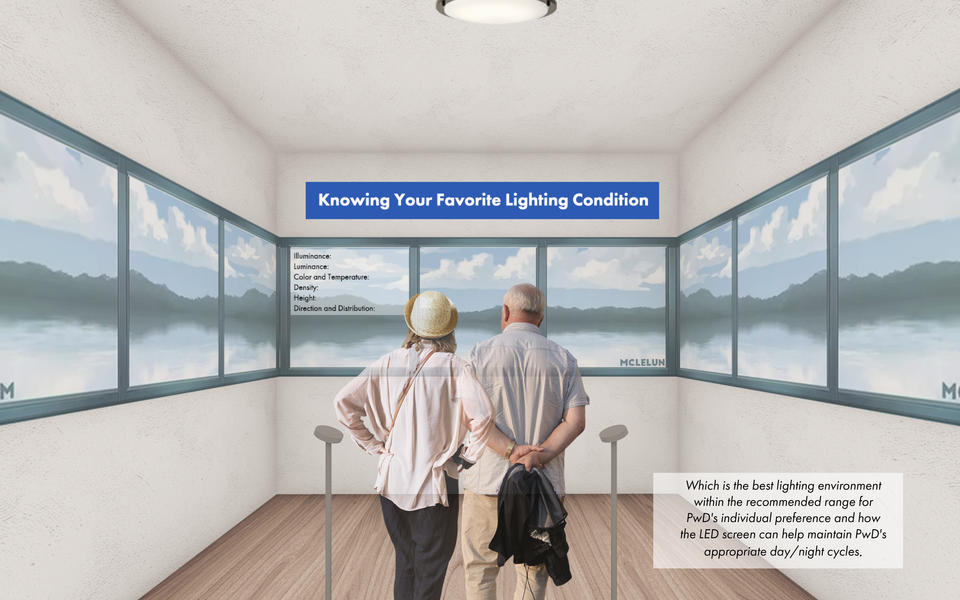

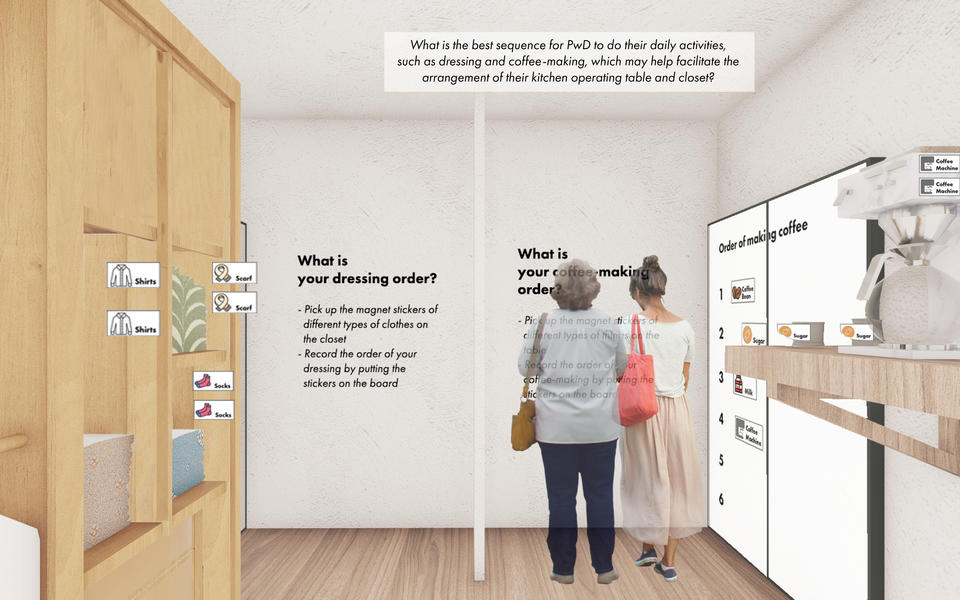

There is a great need for an exhibition to explain the dementia-friendly home environment to the general public. Therefore, a series of annual exhibitions, distributed around the world and adapted to the characteristics of the local home environment, is introduced. These regularly-held and updatable exhibitions can meet the constant new cases and build long-term relationships with people for multiple study visits.

This laboratory immersion exhibition will break through the traditional format of communicating information. During the continuous exploration and interactive activities in the experiment areas, visitors can learn about dementia-friendly home environments to facilitate and customize evidence-based home modifications by themselves. Meanwhile, the simulation of the real home environment brings visitors through a more immersive experience. The exhibition will also help promote further research in this field through bringing together PwD, caregivers, researchers, and designers to communicate the best practice. In the end, the exhibition should provide support for creating dementia-friendly environments and help improve PwD’s quality of life.

Current Research State

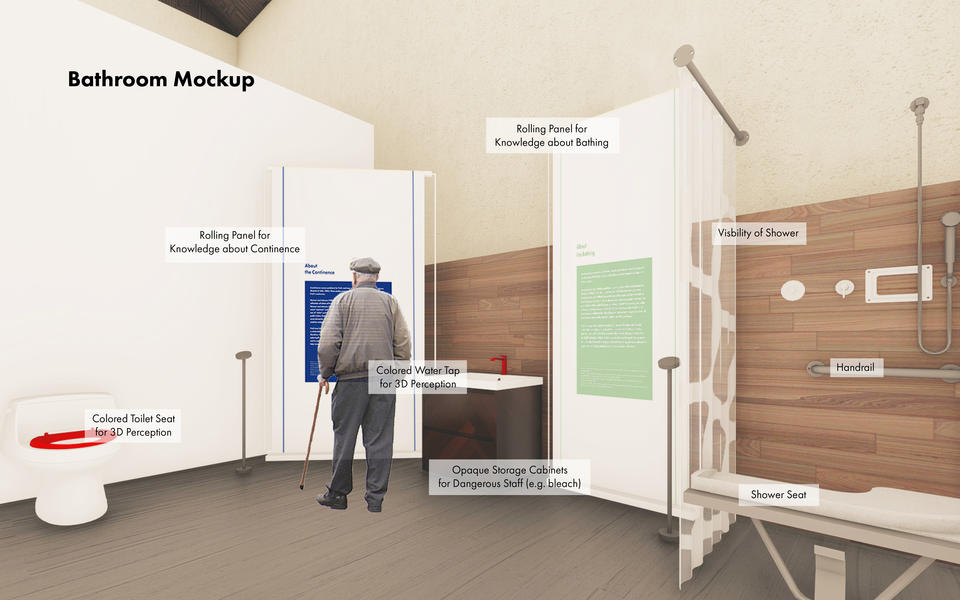

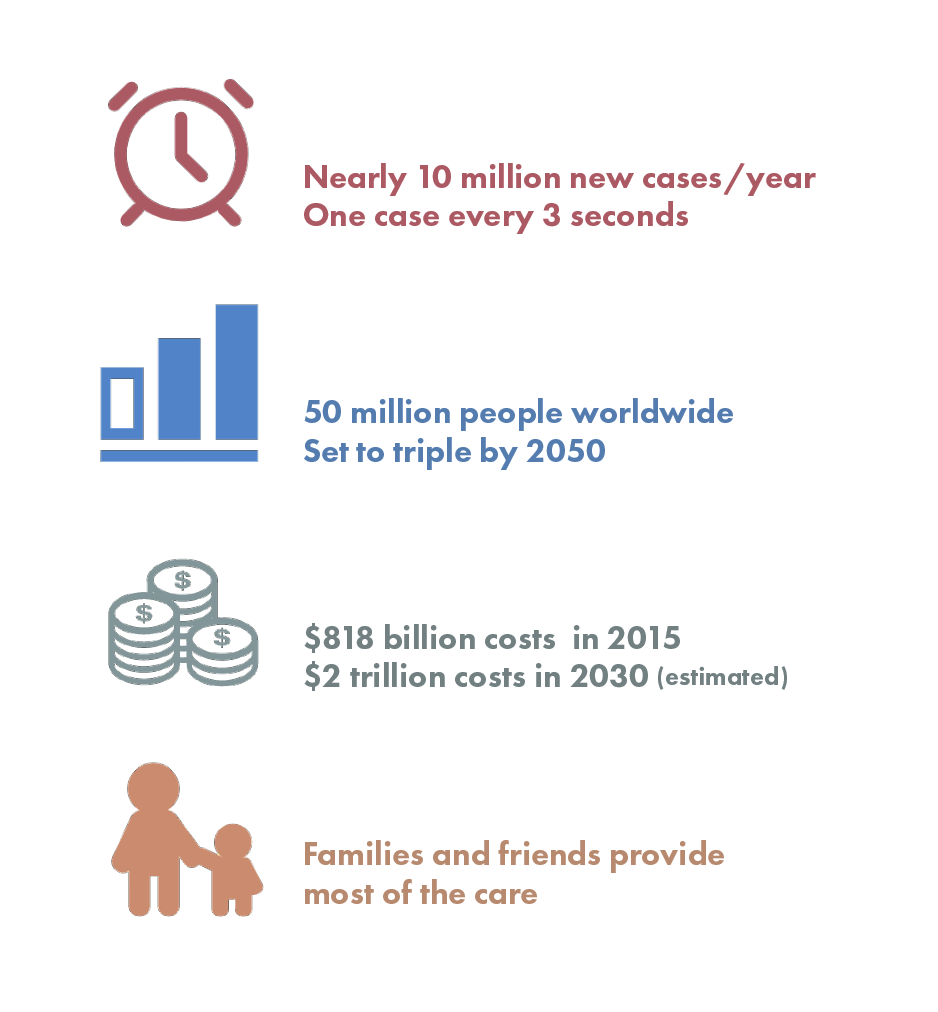

More than 50 million people are living with dementia worldwide, with nearly 10 million new cases emerging each year.1 Dementia is a syndrome leading to deterioration in cognitive functions. Abilities of people with dementia (PwD), such as memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning, language, and judgment, decline gradually,1 which may have adverse impacts on their capability to negotiate, and/or be adapted to the daily living environment. Activities of daily living (ADLs), including bathing and showering, personal hygiene and grooming, dressing, toilet hygiene, functional mobility and transferring, and self-feeding,2 becomes more challenging as dementia symptoms advance.3

Ample evidence indicates that built environmental features (e.g., lighting, noise, temperature, sensory inputs, furnishing, building layouts) influence the daily living of PwD.4 These features fall into three categories5,6 : (1) ambient environment (the least permanent features), such as calming music;7 (2) interior design (less permanent features), such as homelike materials and furniture;8 (3) architecture design (relatively permanent features), such as building layouts.9 While previous research suggested that specific design interventions were beneficial to PwD4 , the concept of the dementia-friendly environment has been created to support a cohesive system that recognizes the experience of PwD and assists them to be engaged in meaningful daily lives10. Advocated by multiple major organizations11, 12, 13, dementia-friendly environments can be developed in communities, hospitals, or wards, targeting PwD and/or caregivers14. Being dementia-friendly in healthcare settings, as Lin stated, requires improvement in multiple areas including environmental modifications, staff education, etc.14. The Kings Fund also describes that supportive design principles of a dementia-friendly environment should promote familiarity, legibility, wayfinding, orientation and meaningful daily activities15.

Among these studies, the majority have largely focused on institutions (e.g., dementia care facility, memory care facility, assisted living facility). However, among different types of living arrangements, the home has been uniquely preferred by PwD and their families for aging in place16 . Current research in the home environment for PwD focused on the impacts on their activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Influences on sleeping, safety and independence problems have also been investigated.17 Aging at home has profound significance and benefits like maintaining the affinity and constancy of the surrounding environment and maintaining the social network.18 However, staying at home also presents many challenges—for example, higher fall risk, safety problems, environmental challenges, and unmet physical demands.19, 20 Among those topics, home safety has been demonstrated as one of the biggest concerns, which is related to: (1) falling; (2) using kitchen, food, and medication inappropriately; (3) wandering, exiting and getting lost; (4) injuring self or others using sharp objects; and (5) responding slowly to crisis.21, 22

Van Hoof and Kort proposed the concept of “A design for a dementia dwelling,” which provided related home modification suggestions for PwD.23 The interventions that have been studied on home environments for PwD can generally be categorized as (1) using assistive devices; (2) modifying home environments appropriately; (3) modifying or rearranging objects such as furniture, utensils, equipment, and other items; and (4) simplifying task processes.17

Image

▲ Data from World Health Organization

Critical Research/Design Strategies

Image

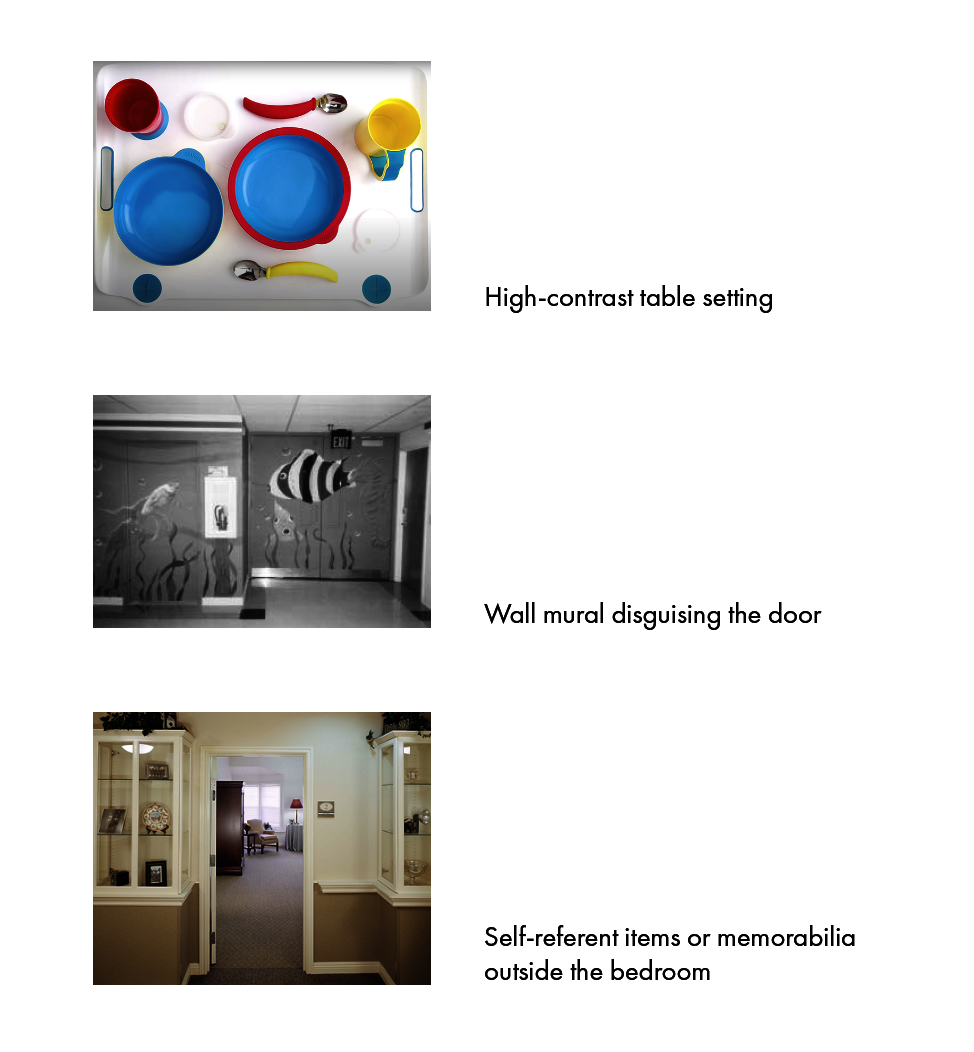

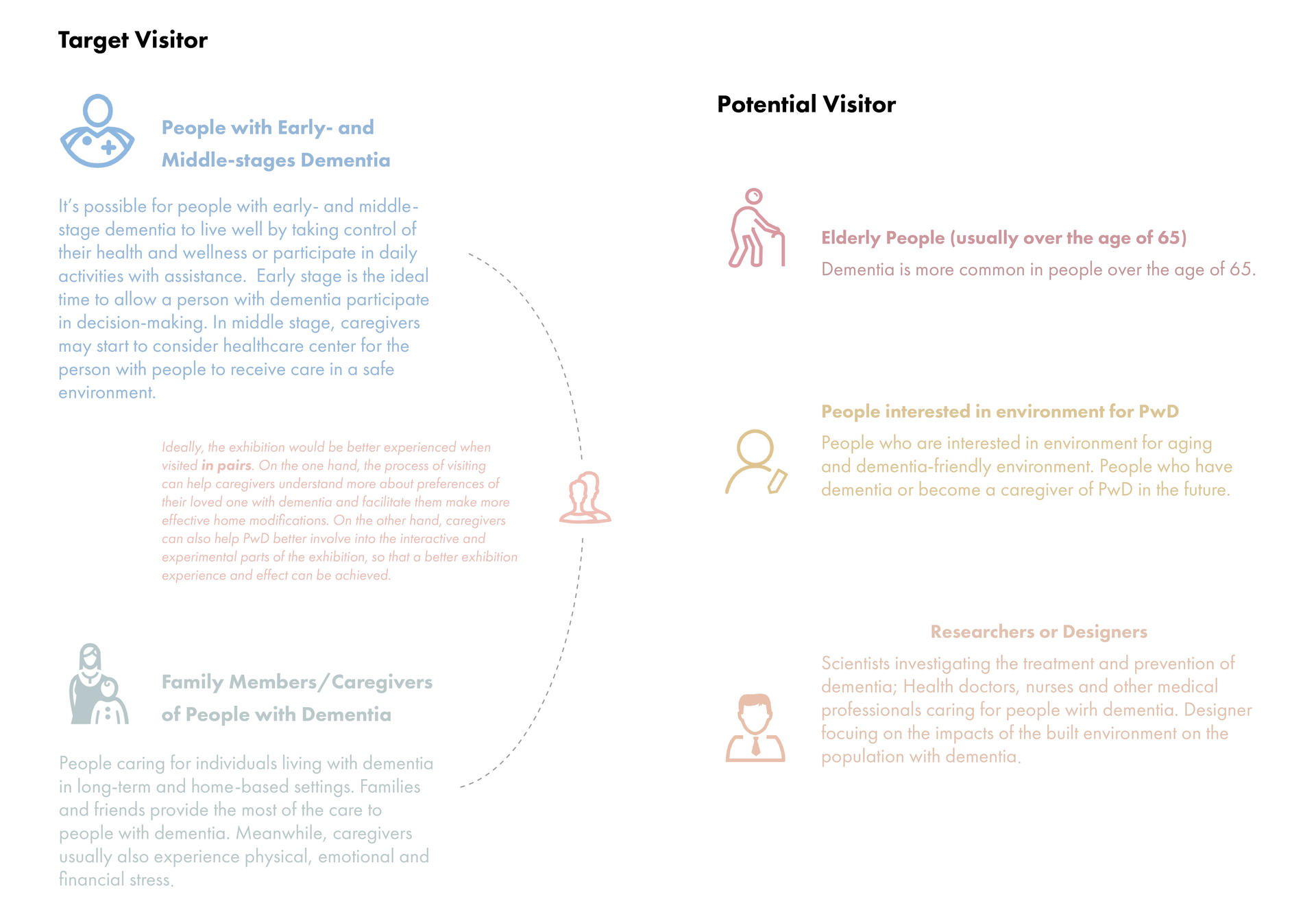

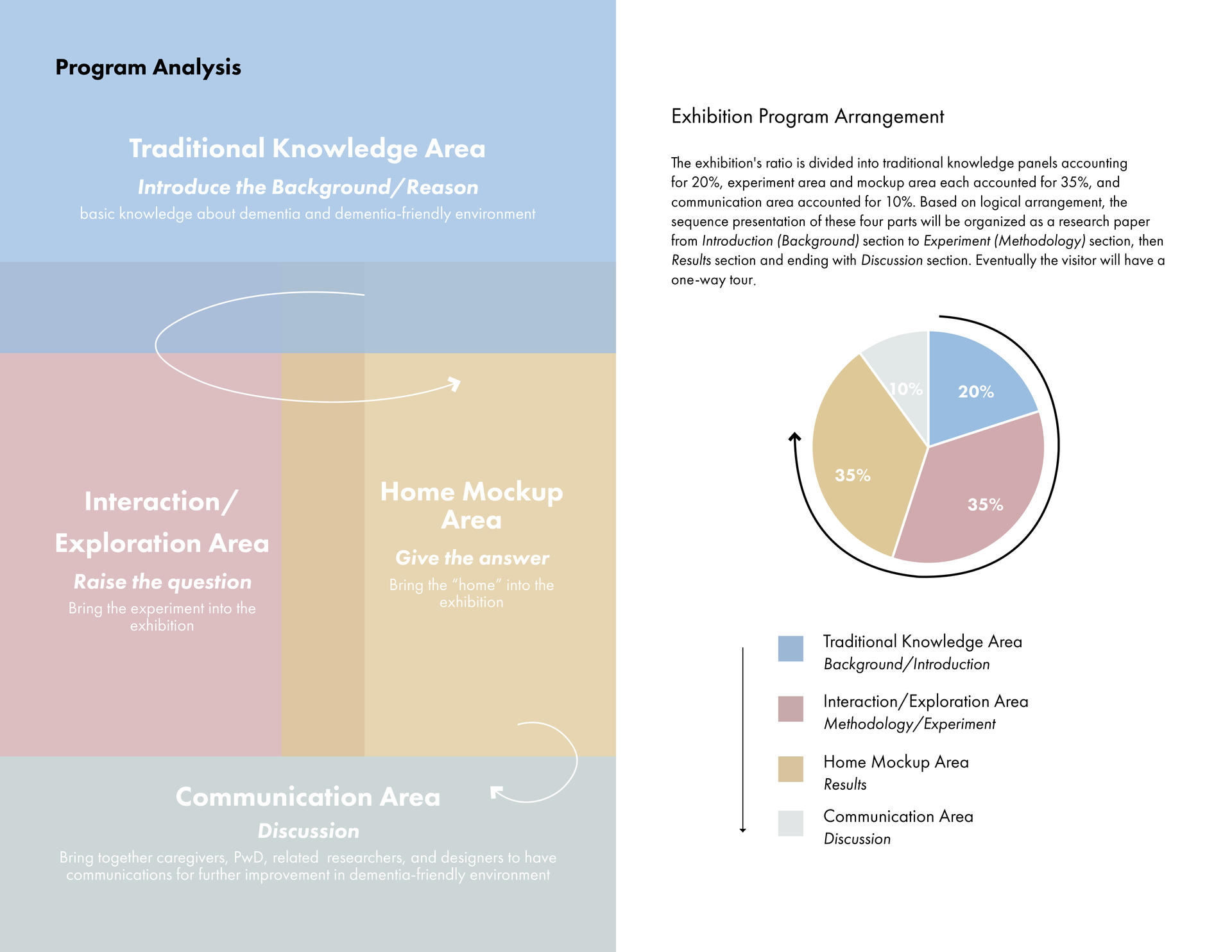

▲ Examples of Dementia-friendly Built Environment Features

Existing research shows the impacts of built environmental features on PwD's daily lives. However, how to apply the modifications into PwD's own home wisely and optimally still needs further investigation. Design tailored for specific individuals was frequently recommended for home environments for PwD.17 The significance of tailored design may be attributed to nuanced differences among the lives of PwD. These differences may result in some particular approaches based on theoretical studies more or less effective in practice. There is little research investigating the most effective environmental cues regarding the selection of colors and image types.24, 25 In addition, it suggested that there is a gap between theoretical and practical applications. For instance, prior research found that using mirrors on the door worked effectively to prevent PwD’s exit attempts26 while a participant in an in-depth interview repeatedly emphasized reflective materials should not be used due to the confusion they caused.27 Similarly, one study found that calming music could lead PwD to be less agitated,28 but it was reported by one participant that music may lead to hallucinations especially for PwD who are sensitive to some sounds.27

Meanwhile, the intended population of dementia-friendly home environments - people with early- and middle-stages dementia and their caregivers (e.g., the family members) usually have little knowledge about the best practice . Therefore, it is of great importance through this exhibition to educate related groups (e.g., family members or caregivers of PwD) about the current research state of dementia-friendly home environments. The exhibition should facilitate evidence-based dementia-friendly home modification that can help PwD stay home longer and avoid relocating in nursing homes.

The exhibition will provide easy access to relevant user groups through a laboratory immersion format. To ensure that the exhibition can go to more places to educate more people about the dementia-friendly environment, the exhibition will distribute around the world and adapted to the characteristics of the local home environment, is introduced. These regularly-held and updatable exhibitions can meet the constant new cases and build long-term relationships with people for multiple study visits. As previously mentioned about the tailored design for specific individuals, the exhibition will not only present basic evidence-based research results but also involve a number of interactive experiences. Through close interactions in the experiments, visitors will explore in an immersive experience to find the most effective home modification strategies for the person with dementia. Meanwhile, in these interactive experiences, PwD and their families are involved in the decision-making process about customizing their own home modifications, which has significant benefits for PwD's well-being and the effectiveness of those dementia-friendly home modification strategies.

In addition, this exhibition can bring together PwD, their families, designers and researchers to involve in the design and planning process and establish better communication. Therefore, this exhibition can play as a good platform to promote mutual communications within the dementia community. Such communications will not only improve the quality of life of PwD, but also leverage the research development in related fields.

As a result, through the continuous progress of this exhibition and participations of visitors, two research questions will be answered - what are the barriers and facilitators for PwD to age in place at home? And what is the optimal dementia-friendly home environment?

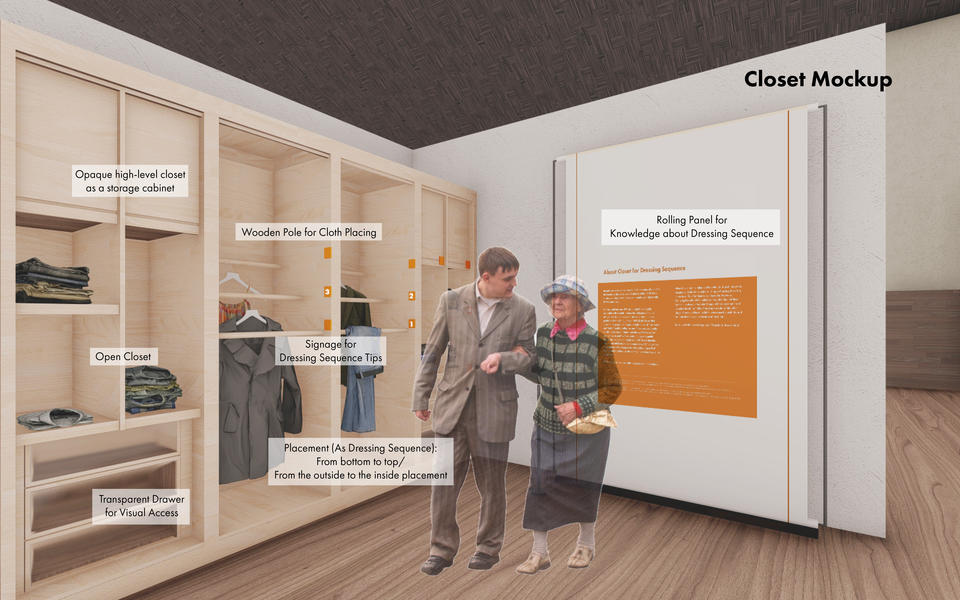

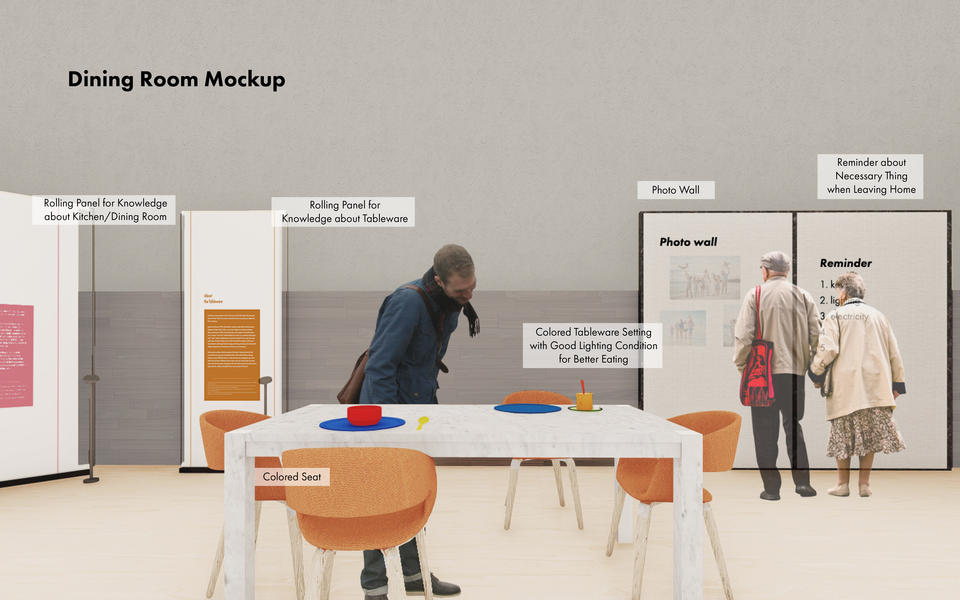

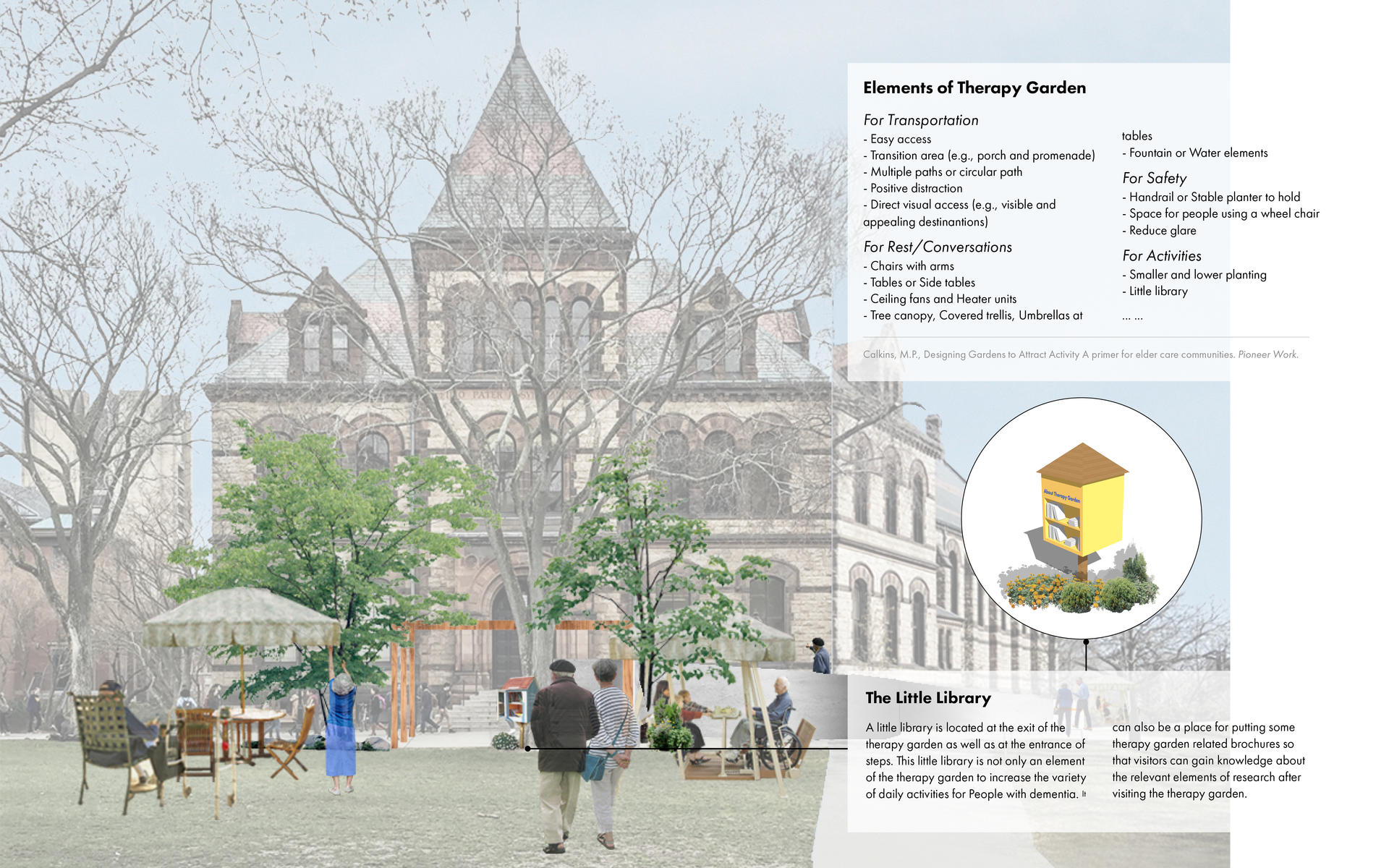

Image

Image

Image

Therapy Garden

Image

Experiment Area

Home Mockup Area

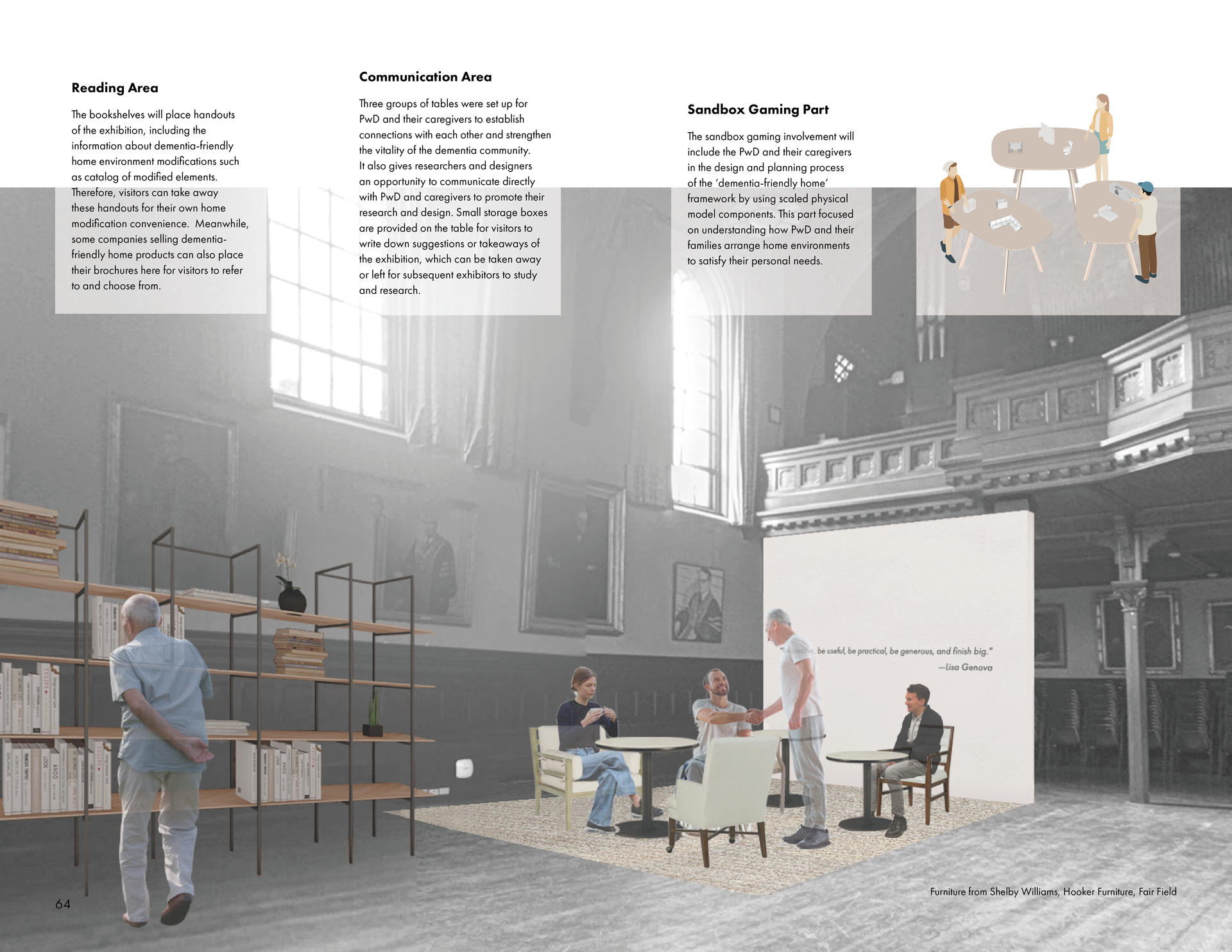

Communication Area

Image

“Be creative, be useful, be practical, be generous, and finish big.”

—Lisa Genova

Endnotes

1. World Health Organization. Dementia. World Health Organization, Sep 2020, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

2. Hardy, S. E. "Consideration of Function & Functional Decline". Williams, B.A., Chang, A., Ahalt, C., Chen, H., Conant, R., Landefeld, C.S., Ritchie, C., Yukawa, M. (Eds.). Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Geriatrics, Second Edition. (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2014)

3. Alzheimer’s Association. What Is Dementia?. Alzheimer’s Association, accessed December 7th, 2020 https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia

4. Marquardt, G., K. Bueter, and T. Motzek. "Impact of the Design of the Built Environment on People with Dementia: An Evidence-Based Review." [In eng]. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 8, no. 1 (Fall 2014): 127-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758671400800111.

5. Anderiesen, H., E. J. A. Scherder, R. H. M. Goossens, and M. H. Sonneveld. "A Systematic Review - Physical Activity in Dementia: The Influence of the Nursing Home Environment." Applied Ergonomics 45, no. 6 (Nov 2014): 1678-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2014.05.011. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000340697100035.

6. Harris, P. B. , G. McBride, C. Ross, and L. Curtis. "A Place to Heal: Environmental Sources of Satisfaction among Hospital Patients." Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32, no. 6 (2002): 1276-99.

7. Remington, Ruth. "Calming Music and Hand Massage with Agitated Elderly." Nursing Research 51, no. 5 (2002): 317-23. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200209000-00008. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200209000-00008

8. Cutler, L. J., and R. A. Kane. "Post-Occupancy Evaluation of a Transformed Nursing Home: The First Four Green House® Settings." Journal of Housing for the Elderly 23, no. 4 (2009): 304-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763890903327010. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=10527419….

9. Marquardt, G. "Wayfinding for People with Dementia: A Review of the Role of Architectural Design." [In eng]. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal 4, no. 2 (Winter 2011): 75-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758671100400207.

10. Davis, Sandra, Suzanne Byers, Rhonda Nay, and Susan Koch. "Guiding Design of Dementia Friendly Environments in Residential Care Settings: Considering the Living Experiences." Dementia 8, no. 2 (2009): 185-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301209103250. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1471301209103250.

11. World Health Organization. Dementia: a public health priority. World Health Organization, 2012, http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/

12. Alzheimer’s Society. Dementia Friendly Communities.Alzheimer’s Society, (2016) https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/dementiafriendlycommunities.

13. Dementia Action Alliance. The right care: creating dementia friendly hospitals. Dementia Action Alliance, 2013, www.dementiaaction.org.uk/assets/0000/1688/Dementia_Action_Alliance_New…

14. Lin, Shih-Yin. "'Dementia-Friendly Communities' and Being Dementia Friendly in Healthcare Settings." [In eng]. Current opinion in psychiatry 30, no. 2 (2017): 145-50. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000304. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27997454

15. The Kings Fund. Is your ward dementia friendly? The EHE environmental assessment tool. The Kings Fund, 2014, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/EHE-dementia-assessmen….

16. Soilemezi, Dia, Amy Drahota, John Crossland, Rebecca Stores, and Alan Costall. "Exploring the Meaning of Home for Family Caregivers of People with Dementia." Journal of Environmental Psychology 51 (2017/08/01/ 2017): 70-81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.007.

17. van Hoof, J., H. S. Kort, H. van Waarde, and M. M. Blom. "Environmental Interventions and the Design of Homes for Older Adults with Dementia: An Overview." [In eng]. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Care and Related Disorders & Research 25, no. 3 (May 2010): 202-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317509358885.

18. Aminzadeh, F., W. B. Dalziel, F. J. Molnar, and L. J. Garcia. "Meanings, Functions, and Experiences of Living at Home for Individuals with Dementia at the Critical Point of Relocation." [In eng]. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 36, no. 6 (Jun 2010): 28-35; quiz 36-7. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20100303-02.

19. Soilemezi, D., A. Drahota, J. Crossland, and R. Stores. "The Role of the Home Environment in Dementia Care and Support: Systematic Review of Qualitative Research." [In eng]. Dementia (London) 18, no. 4 (May 2019): 1237-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217692130.

20. Gitlin, L. N., N. Hodgson, C. V. Piersol, E. Hess, and W. W. Hauck. "Correlates of Quality of Life for Individuals with Dementia Living at Home: The Role of Home Environment, Caregiver, and Patient-Related Characteristics." [In eng]. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 22, no. 6 (Jun 2014): 587-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.11.005.

21. Gitlin, Laura N., and Mary Corcoran. "Making Homes Safer: Environmental Adaptations for People with Dementia." Alzheimer's Care Today 1, no. 1 (2000). https://journals.lww.com/actjournalonline/Fulltext/2000/01010/Making_Ho….

22. Green, Y. S. "Safety Implications for the Homebound Patient with Dementia." [In eng]. Home Healthc Now 36, no. 6 (Nov/Dec 2018): 386-91. https://doi.org/10.1097/nhh.0000000000000701.

23. Van Hoof, Joost, and Helianthe S. M. Kort. "Supportive Living Environments: A First Concept of a Dwelling Designed for Older Adults with Dementia." Dementia 8, no. 2 (2009/05/01 2009): 293-316.

24. Motzek, T., K. Bueter, and G. Marquardt. "Environmental Cues in Double-Occupancy Rooms to Support Patients with Dementia." [In eng]. Herd 9, no. 3 (Apr 2016): 106-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586715619740.

25. Wood, S., K. F. Mortel, M. Hiscock, B. G. Breitmeyer, and J. S. Caroselli. "Adaptive and Maladaptive Utilization of Color Cues by Patients with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer's Disease." [In eng]. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 12, no. 5 (1997): 483-9.

26. Mayer, R., and Stuart J. Darby. "Does a Mirror Deter Wandering in Demented Older People?". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 6, no. 8 (1991): 607-09. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.930060810. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gps.930060810.

27. Wang, W. . Does a "dementia-friendly home design" work in real-world? [Unpublished manuscript] (2020). School of Public Health, Brown University.

28. Remington, R. (2002). Calming Music and Hand Massage With Agitated Elderly. Nursing Research, 51(5), 317-323. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200209000-00008

Image Credits

Melanie Potter. This tableware is specifically made for people with Alzheimer's, AOL.COM, Aug 21st, 2015, https://www.aol.com/article/2015/08/21/this-tableware-is-made-specifica…

Kincaid, C., and J. R. Peacock. "The Effect of a Wall Mural on Decreasing Four Types of Door-Testing Behaviors." Journal of Applied Gerontology 22, no. 1 (2003): 76-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464802250046. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0733464802250046.

Memory boxes outside of memory care resident’s room. Douglas Pancake Architects. https://archiveglobal.org/promoting-senior-health-in-interior-environme…