ABSTRACT

This thesis explores conditions of mutability in the landscape through the lens of the Earth’s biomass, particularly the living beings whose systemic, functional and aesthetic values are misrepresented or undervalued. Relegated to the abandoned, derelict and forgotten landscapes, the presence of these living things has often come to represent decay, blight, lack of resources, and care. However, in the light of the global environmental crisis and in search of viable solutions to clean up the environment and curb greenhouse gas emissions, it has become apparent that the spontaneous, opportunistic qualities of these living beings can provide unparalleled opportunities to do so in cost effective strategies.

Composed of five parts, the study includes [1] a novella, which tells a story of a sentient presence that serves as the collective consciousness of all living things past and present, [2] a theoretical framework that uses ideas such as landscape, mutability, or utopia to reposition the discipline of landscape architecture, [3 and 4] chapters containing a set of regenerative and diversity practices that aim to exemplify the ideas previously explored, and [5] a final focus on the concept of diversity, this time to explore the biomass as a potentially diverse physical manifestation of the genetic knowledge of life.

In this trajectory, the thesis attempts to explore an argument where diversity is linked to sustainability, ecological balance, resilience and democracy. It proposes that diversity is supported by mutability to operate as an integral part of everyday life to suggest that it can be regarded as a manifestation of utopia. Finally, the thesis returns to the idea of diversity in social cultures and offers a reflection on practicing diversity on the entire spectrum of the living world.

Thesis Statement

Mutability in the landscape is explored through the lens of the Earth’s biomass and a case is made in defense of diversity as a state vastly broader than the sum of its parts; diversity is an integral element of theoretical discourse, as well as a manifestation of mutability, and thereby utopia, in the physical world.

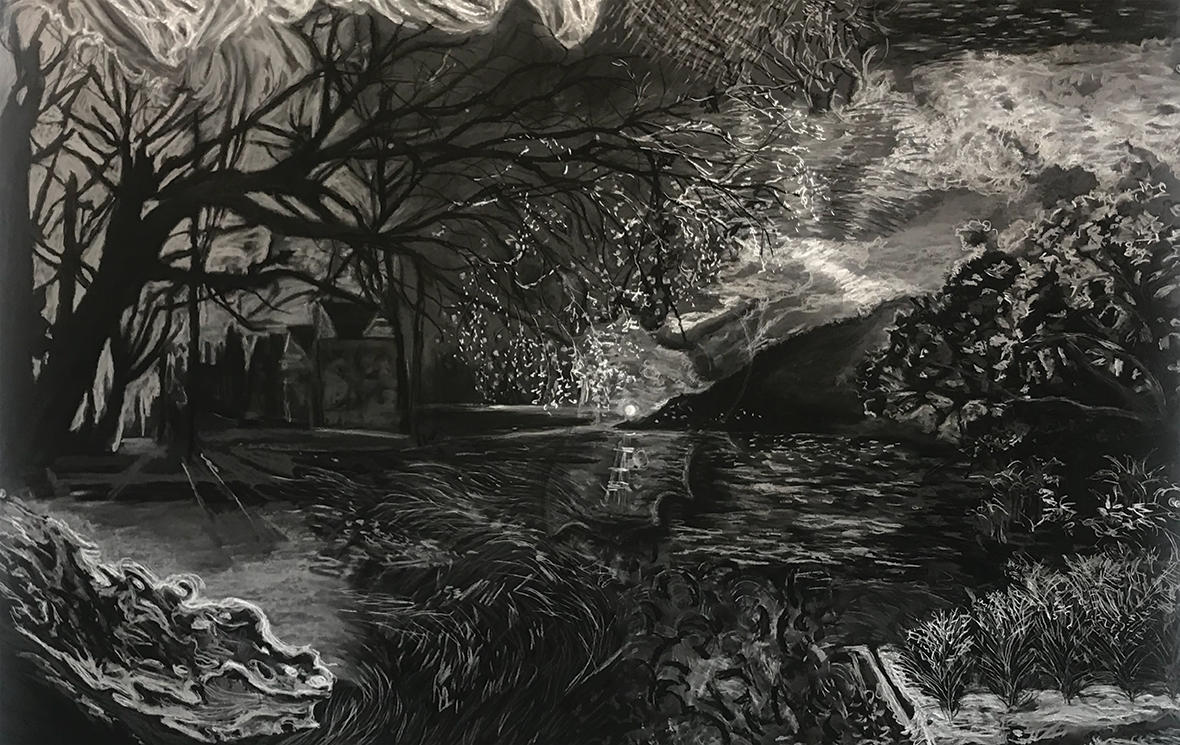

Image

Mutable Landscapes. Charcoal on paper.

A representation of mutability in the landscape, the drawing is an amalgam of different landscapes and seasons coalesced in a singular image.

Objective

The objective of this thesis is to demonstrate how mutability occurs in Nature through the lens of the Earth’s biomass and how its regenerative processes can be applied to diversity practices that enable and sustain all of life. Examining the historical origins of humanity’s relationships with Nature, particularly through the curation of lawns and gardens, the research attempts to link back the modern-day practices to their historical contexts to elucidate the reasons behind their engendered meanings and values. The examination of these legacies reveals the practices of exclusivity, control, and captivity which can be the antithesis of mutability and thereby a threat to diversity. However, by providing examples of regenerative principles applied to the practices of cultivating the lawn and the garden, it is hoped that a possible middle ground is reached. Furthermore, when regenerative principles are applied to diversity practices through various configurations in the landscape, they enable mutability to operate within the biomass. The thesis attempts to make a case in defense of the existence of these — and all living beings — through the argument that diversity is directly linked to sustainability, environmental and cultural equity and justice, ecological balance, resilience and democracy. It is therefore hoped that the understanding of this may reveal to landscape architecture practitioners and the public alike, how diversity in the natural world must be cultivated much like the diversity in the human world. It is argued that the biomass is the physical manifestation of the genetic knowledge of life, the existence of which is wholly tied to promulgating theoretical frameworks and discourse, and the practice of everyday life.

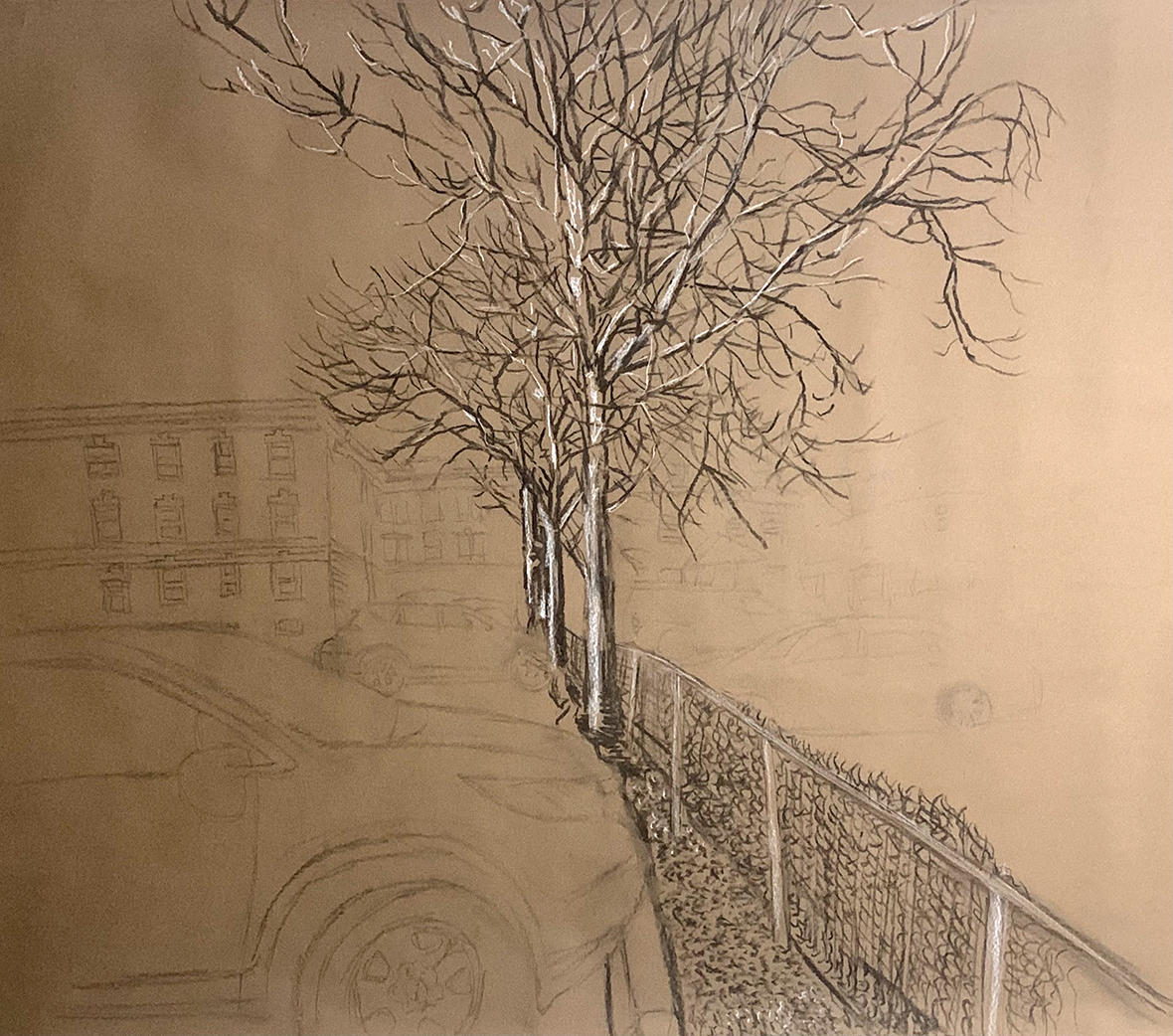

Image

Pier Roost in East Boston.

Remnants of an industrial pier in East Boston are occupied by cormorants who use the pilings for a safe nighttime roost and, perhaps, to hunt by dusk and dawn.

Image

The Hudson Yards before the High Line.

A portion of derelict infrastructure at Hudson Yards, NYC, just prior to the development of the last phase of the High Line. Spontaneous vegetation that colonizes the structure in the photo will be replaced by “chosen” plants, whose values are determined by humankind.

Image

The Phillipsdale Barge.

Abandoned and forgotten, save for the plants that are capitalizing on its demise, the barge hosts successional layers of life, which continuously perpetuate new life through cycles of regeneration.

Image

Marginalized Biomass.

Spontaneous Ailanthus altissima, Chinese tree-of-heaven, volunteer as hedgerow trees in a permeable fringe between two parking lots, providing free ecological services.

Image

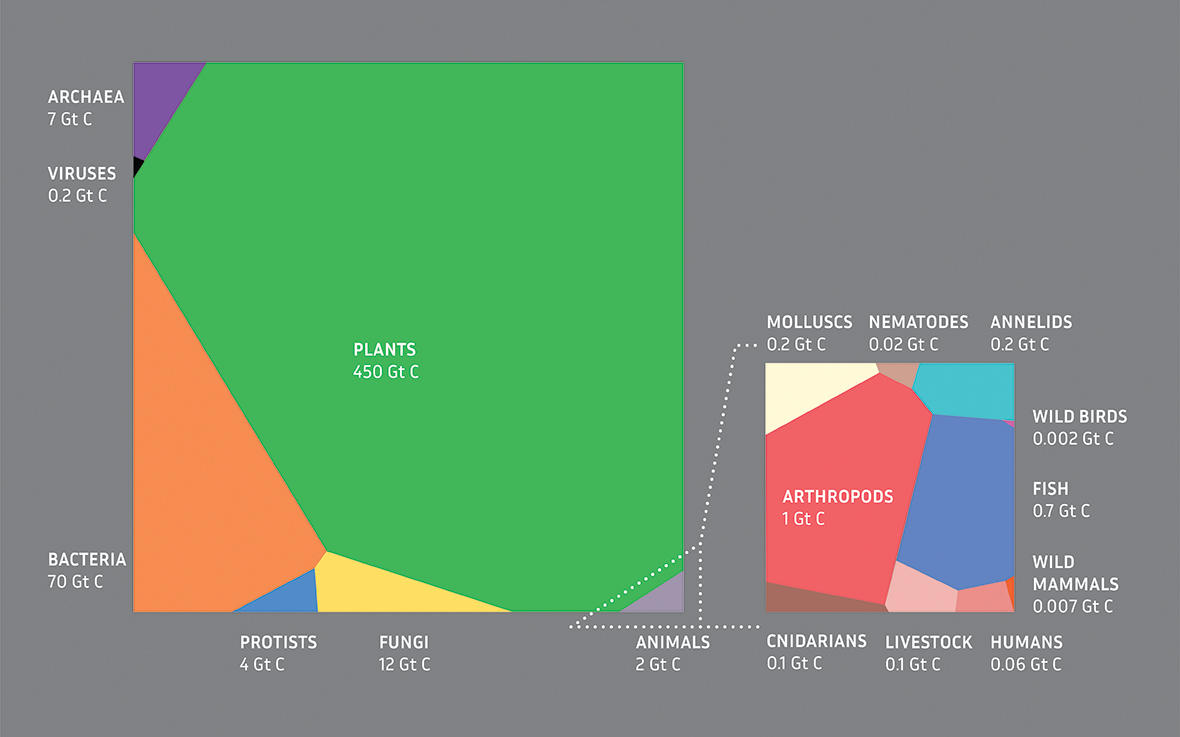

The Global Biomass.

A Voronoi diagram showing the distribution of the biomass, where each taxa is represented by a cell, the area of which is proportional in relation to others. Biomass is measured in gigatons of carbon.

Earth’s living things, including humans are its Biomass. Measured in gigatons of carbon that biomass makes up for approximately 550 gigatons of organic carbon. Terrestrial plants are considered to hold the greatest biomass in the world. Together with the microbes and the fungi, they account for some 532 gigatons of carbon and are capable of sequestering a gargantuan amount of atmospheric carbon and storing it within their tissues and the Earth’s crust. Along with carbon sequestration, organic matter in the soil, helps precipitation percolate to groundwater instead of becoming runoff. Keeping the microbiota in the soil thriving, helps sustain everyone else up the food chain, including humans. Beyond that, the bacteria and fungi in the soil are capable of breaking down some of the most recalcitrant synthetic pollutants into harmless compounds.

Source: The biomass distribution on Earth, Yinon M. Bar-On, Rob Philips, and Ron Milo, PNAS Journal, April, 2018.

Regenerative Practices

Regenerative qualities of our planet are owed to its biomass, an amalgam of interconnected living things across the globe. Regenerative Practices come out of Regenerative Agriculture, which focuses on a bottom-up approach to organic practices that start with sustaining healthy, viable, live soils. Similarly, regenerative practices are initiatives that are applied to any landscape, land management strategies to ensure that they work with the natural systems.

Origins of regenerative agriculture can be traced back to organic practices and sustainable practices. While both practices probably started to come about around the same time, they were not necessarily developed together or in awareness of one another. Organic practices were developed in response to the negative impacts of practices which utilize synthetic inputs (such as fertilizers, pesticides and genetically modified organisms (GMOs)), while sustainable practices, favor the use of materials that are renewable. However, there are substantial gaps between the two systems. While organic practices limit the use of synthetics, they are not necessarily biodiverse and they do not limit the use of resources, some of which are finite or not renewable. For example, organic practices do not exempt the use of monocultures or intensive irrigation or the addition of mined minerals. Similarly, sustainable practices do not rely on biodiversity or organic practices but simply on the ability of making materials available indefinitely. For example, growing bamboo as a sustainable construction material, does not guarantee that the resources used to grow that bamboo are organic or renewable. Therefore, the fundamental gaps that emerge from the two systems, inevitably make them unsustainable. Regenerative Agriculture emerges out of the need to fill the gaps in the two systems, while encompassing their principles within a more integrated framework of holistic practices.

A Brief History of the Lawn

Lawn’s origins and its various manifestations began to take shape in Europe from around the 16th century. Back then, the word lawn described a clearing in the woods. In the 17th century, “lawn” was used to describe a portion of uncultivated land that was covered in grass. And in the 18th century, it referred to an area of a pleasure garden containing grass that was kept tightly mown.

American lawns did not make much of an appearance until after the Civil War, but the true proliferation of lawns in the United States is owed to the three major movements of urbanization in the country’s history.

The first of these started during the Civil War with the expansion of the railroad, streetcars and trolleys that prompted the development of suburban communities. Together with the public park movement, begun by none other than Frederick Law Olmsted, new suburbs sprang up along the East Coast. The second great movement took place in the 1920s, when the automobile enabled further expansion of the suburbs, along with the explosive popularity in golf. The third and the biggest urban sprawl came after World War II, when the federal government financed low-cost mortgages for veterans and a countrywide funding for interstate infrastructure.

In America as in Europe, lawns were seen as a mark of wealth and affluence, especially because cultivating and maintaining them was an extremely expensive proposition. Even with the invention and advances of the lawn mower, keeping the lawns maintained was not an exact science. The post WWII Green (Chemical) Revolution, which provided unequivocal opportunities to standardize agriculture, had also made growing and sustaining lawns much easier and more accessible, and soon enough having a nice lawn became the standard mark of a successful middle-class American home. In addition to being a status symbol, the lawn provided the perfectly curated illusion of a democratic landscape, because while the landscape lacked walls, the turf served as a buffer between the private home and the public street.

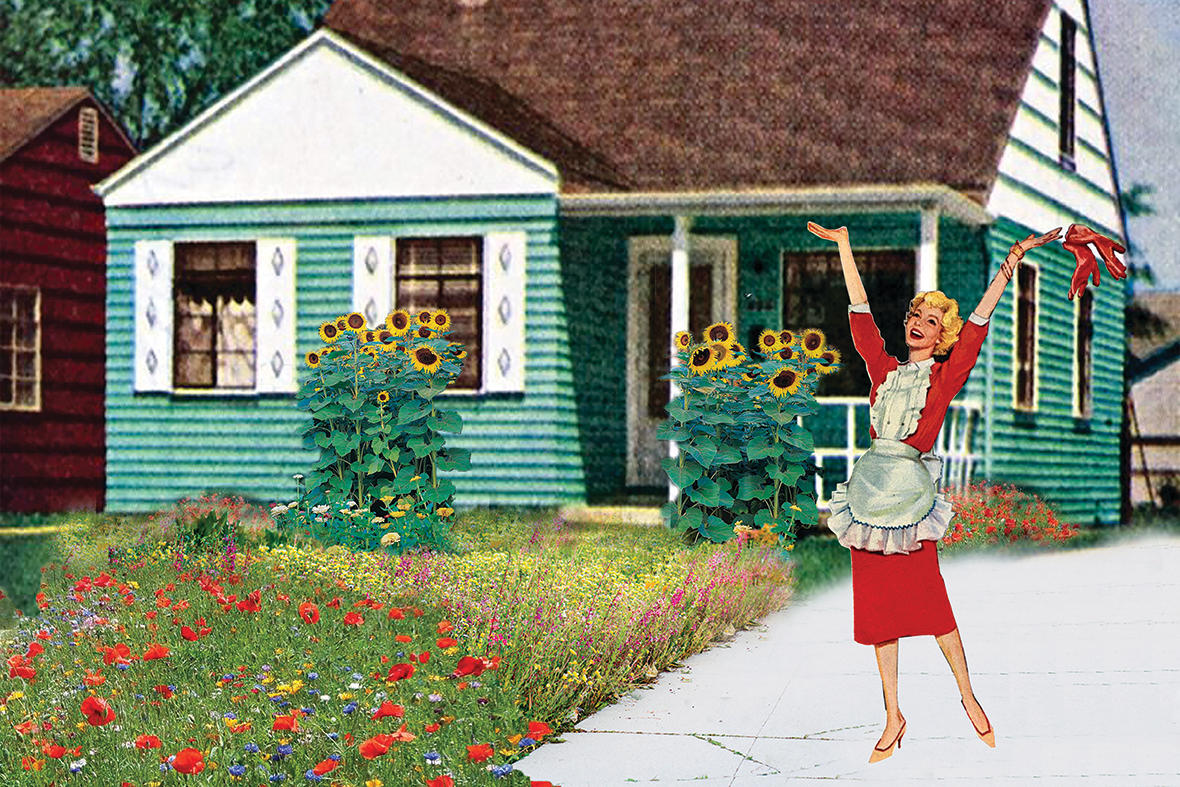

Image

“On My Turf.”

Somewhere between our obsession with a verdant patch and a desire to be immersed in a biophilic lifestyle, lie compulsive tendencies that may accomplish neither but continue to drive at our primordial need to surround ourselves with Nature.

Image

A Place for Repose.

Front lawns outside apartment complexes such as the one pictured, are used by residents during the pandemic to gather in a socially distanced way.

Brief History of the Garden: Paradise is an Enclosure!

Gardens date back to antiquity. The English word “garden” can be traced back to Old High German origin gard or gart. Similar phonetically to the word guard, gardening refers to an enclosure or a compound. (Think kindergarten, “children’s enclosure.”) Perhaps older than the word “garden,” the word “paradise,” also meant a “walled enclosure.” The Greek paradeisos was a term used in translation of the Old Testament to refer to the Garden of Eden. The Greeks appropriated the word from Old Iranian paridaiza(h), which has its origins from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language. The root dheigh literally means “to stick and set up (a wall),” and per “around.”,

Back then, gardens were not necessarily built as they are today, where we introduce natural elements such as vegetation to a prepared space. What was often involved then was quite literally the building of a wall or raising of an enclosure around an area that already had desirable features such as water, vegetation and game animals, such as deer and antelope that were sought after for meat, hide, and trophy. In the Middle East, these desirable areas often started out as natural oases.

Because both words have origins in antiquity, it is not surprising that the combination of the words “paradise” and “garden” has yielded other meanings. With its origins in the Persian Empire, a paradise garden was first associated with an Islamic garden style. As the Persian Empire spread, its garden influence spread with it. But gardens existed well before the Persian Empire. Ancient Egyptians, who were likely the ancestors of Persians, had extensive gardens, including pleasure gardens.

Although through time, “garden” and “paradise” have come to mean significantly different things, the origin of both lies not only in an enclosed, guarded place, which is meant to denote exclusivity, but also a place of pleasure and comfort that is associated with ease of sustenance and feast for all senses. The exclusivity of the garden meant that first and foremost it was free of the dangers associated with wilderness. A garden contained only the desired aspects of Nature, and with time, they evolved to present that nature in an organized and logical manner. Especially significant in the arid regions of the Middle East, a paradise garden had the most sought after element attributed to life, water. Hence, the Islamic garden style had the specificity of featuring water at the center of four quadrants of vegetation, the whole thing contained within a walled interior. Second, it had to be guarded against intruders — other people — who coveted these oases or paradises for themselves.

As the two words diverged, paradise was more attributed to the afterlife or the utopian future, whereas the garden was seen as a physical manifestation of a utopian ideal in the current life or the present.

Image

Garden of the Sheesh Mahal, Amber Palace, India.

Islamic gardens prominently feature water at the center of the garden, surrounded by four quadrants of vegetation.

Image source: “WOWchitecture,” January 2014, http://wowchitecture.blogspot.com/2014_01_01_archive.html.

Image

Opportunities for Biomass.

Espaliered apple trees commune with a variety of herbs atop a NYC terrace. Gardening on a terrace or a rooftop, is akin to gardening on a side of small mountain, where microclimates and a limited soil column present challenges and opportunities alike.

Image credit: Trillium Landscape Design

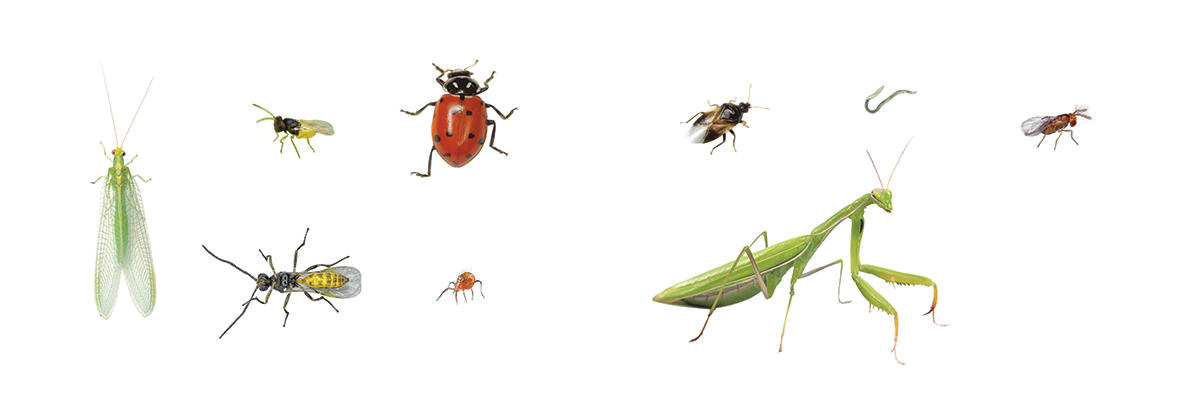

Image

Beneficial Organisms.

Organisms which help control undesirable organisms in the landscape, are deployed as part of a holistic approach of the Integrated Pest Management (IPM) system. Although preference is given to some over others, this approach ensures that there are no long-term detrimental effects to the organisms or the environment.

DIVERSITY

In the English language, we have a specific word to describe the diversity that occurs in nature, biodiversity. The word “diversity” is usually reserved to imply a broader diversity such as the kind that applies in theoretical, social, economic and political frameworks. Throughout this thesis, the word “biodiversity” is intentionally left out and the word “diversity” is instead used in discussion of both the theoretical constructs and living beings. The reason for this is that the coining of the term “biodiversity” has essentially created a binary set, where “biodiversity” and “diversity” are disassociated from each other. While the word “biodiversity” is associated with the natural world, we tend to apply it to animals, plants, insects and “other” such living things, whereas the word “diversity” is reserved for human beings, such as when we speak of diversity of people in school or the workplace. The binary set, which through its virtue of specificity neglects the fact that all of our theoretical constructs and knowledge originate from and are sustained by all of the living things and systems of Earth.

The United Nations Environment Programme defines biodiversity as “the biological variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic, species, and ecosystem level.”1

The Oxford English Dictionary defines diversity as: 1. the state of being diverse; variety. “[T]here was considerable diversity in the style of the reports.” 2. the practice or quality of including or involving people from a range of different social and ethnic backgrounds and of different genders, sexual orientations, etc. “[E]quality and diversity should be supported for their own sake.”2

1Joanna Benn and Amina Darani, “Biodiversity Factsheet,” February 2010.

2“Oxford Languages and Google - English,” Oxford Languages, accessed May 21, 2021, https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/.

Raised Beds, A Micro Guarded Oasis

The origins of paradise and garden trace back to erecting walls around favorable conditions found in Nature, but they were also erected to create favorable conditions. Similarly raised beds were invented to create favorable conditions where none existed but with the added flexibility of scale and ease of deployment. What precipitated the creation of raised beds, most likely had to do with urbanization. Urbanization, which occurred in large part due to the mobility enabled first by rail transit and then expanded by the automobile, required prioritization of infrastructure for that mobility and architecture for domesticity and industry over food cultivation. As industries grew, towns and cities grew alongside them, with agriculture for the most part being relegated to lands outside towns and cities. Very quickly, arable land in cities became converted to space for additional buildings, transit infrastructure and automobiles. What’s more, any remaining land around buildings and houses got redeveloped into landscaping that echoed the symbolism of the Great American Dream, which proudly announced the industrial and commercial successes of a country that could afford to relegate its landscape to a nonproductive and purely aesthetic form.

“There are two things money can’t buy — true love and homegrown tomatoes.” Of course that isn’t everyone’s American Dream. For some people, especially those living in the concrete jungles of a city, having their own patch of green allows them to reconnect with Earth. There’s really nothing quite like cultivating new life; the symbiosis that ensues when you grow your own food. Although there are plenty of private and public gardens across the cities in the US, many of them do not afford most people the opportunity to grow their own food. This is an even bigger issue in very dense and urbanized cities, where the square footage of multi-story buildings greatly outweighs the square footage of open space. On rare occasions, when there is a shared backyard of a multistory building, or a vacant lot that used to be occupied by a building or served as a parking lot, the soil is either severely compacted, contaminated or worse yet paved over. In cases like these, raised beds become essential small oases in which new life can easily be cultivated and maintained.

Image

A Raised Bed for a Tree Pit

A rendering for a raised bed that augments an existing tree pit. The idea is for the bed to capture precipitation and then channel it towards the tree pit opening. As well as providing additional water to the tree, the side compartments can be planted.

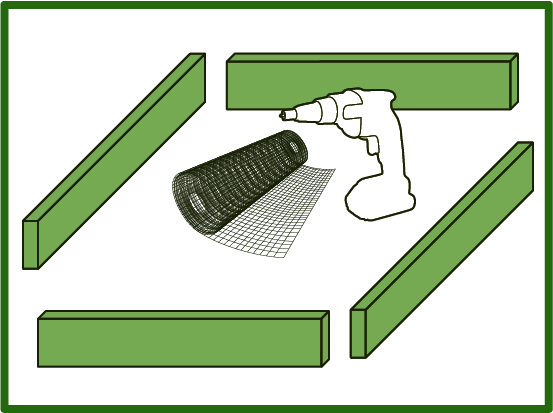

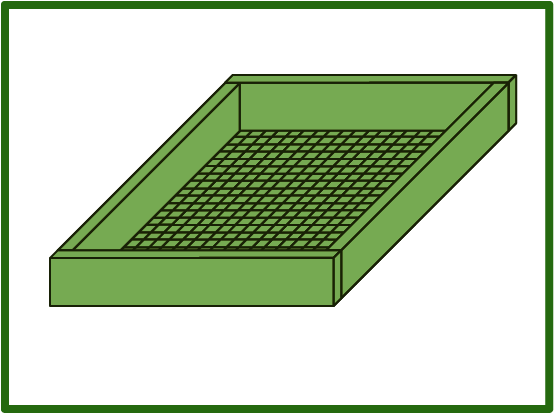

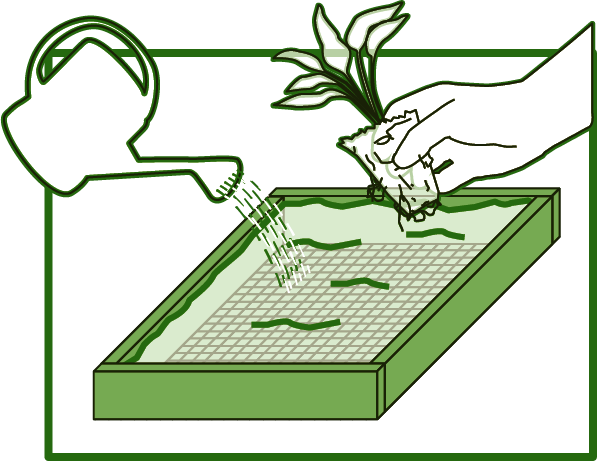

Image

“There are Two Things Money Can't Buy: True Love and Home Grown Tomatoes.”

A basic raised bed requires [1] securing 4 planks to each other, [2] optionally installing hardware cloth to deter animals from below and/or landscape fabric to separate soil and prevent erosion, [3] followed by the addition of soil, [4] water and plants.

Image

The finished raised bed planter installed. Although it was seeded with annuals, it is hoped that the compartments will be colonized spontaneously by opportunistic vegetation.

Freshwater Pond & the Element of Life

What made an oasis, made a paradise.

As it was an essential part of an oasis and thereby the paradise, water was the most important element of the Middle Eastern garden. Water diverted from the Nile in Ancient Egypt was fed through irrigation canals, which also fed decorative ponds and fountains. The Roman Empire adopted and appropriated hydrological technology from the Persian Empire, and both the Italians and the French took to waterworks with an astounding zeal and sophistication.

Life as we know it cannot exist without water. In search of new habitable planets in the cosmos, astrobiologists first look for the presence of water to ascertain the capacity of the celestial bodies to support life. Nothing animates a landscape like water. If water’s movement, translucency, and reflective capacities weren’t enough to animate the landscape, water’s life enabling capacities attract and activate all of life.

The creation of a pond — a small body of water in a depression of earth — is another microcosm of what we find in Nature and what we can adapt to a smaller footprint in the patchwork of urban ecology. Building an artificial pond is a lot simpler and cheaper than is imaginable and this chapter will attempt to explain how to do so and the benefits behind it. A small water feature can enliven even the smallest backyard, however for the purposes of diversifying the biomass, we will discuss the building of a pond, the dimensions and typology of which are designed to support life year-round.

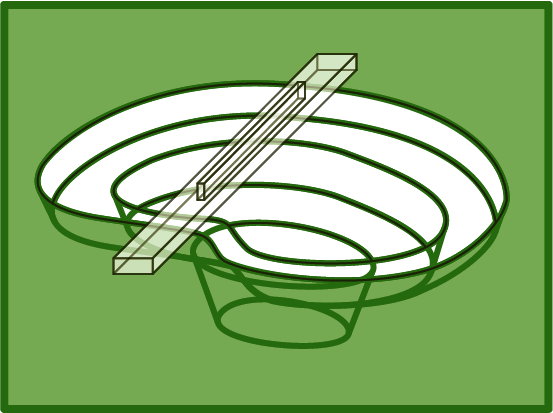

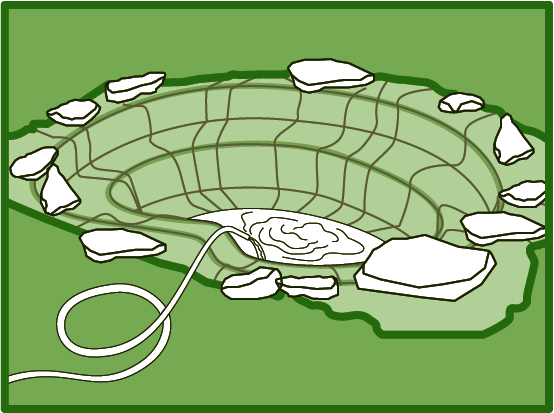

Image

An illustrative drawing of a pond showing marginal shelves of the pond for housing vegetation at different levels of submersion, and the laying of a rubber liner that will serve as a watertight membrane.

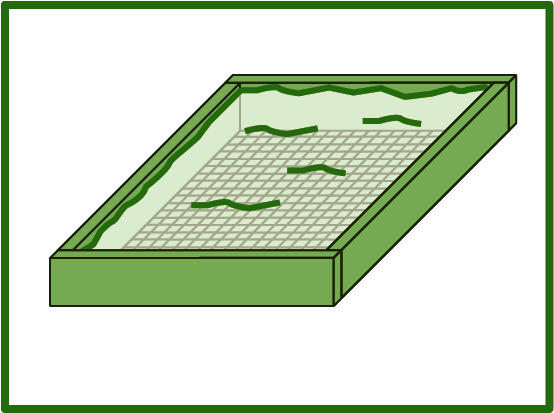

Image

"How To Build A Pond."

Building a pond: [1] The pond outline is clearly marked out on the ground, [2] the pond is dug with care taken to ensure all sides are level, [3] an underlayment is installed to protect the rubber liner, [4] is filled with water and edged with rocks.

Image

A Pond in Harlem, New York City.

Green Roofs, Biomass in the Sky

The first green roofs were hanging. Perhaps the earliest recorded example of cultivation of plants atop buildings were the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Regarded as one the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Hanging Gardens were reported to have existed during either 6th or 7th century BC, depending on whether the gardens are attributed to the Babylonaian king Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled between 605 and 562 BC or to the Assyrian king Sennacherib, who ruled between 704-581 BC. To date, there is no archeological evidence that the wonder ever existed in Babylon and there is a lack of contemporaneous documentation in Babylonian sources describing the Hanging Gardens. However, extensive records exist of the gardens in Nineveh, an ancient Assyrian city in upper Mesopotamia (modern-day northern Iraq). There was a tradition of Assyrian royal garden building and king Ashurnasirpal II who ruled between 883-859 BC, had created a canal which cut through mountains. Following his lead, King Sennacherib constructed the massive 50 kilometer canals and aqueducts that were necessary to bring more water into Nineveh from the mountains. Well documented accounts, archeological remains and inscriptions elucidate the implementation of various hydrological technologies, including the use of the Egyptian water screw or the screw pump to raise the water above ground level to irrigate the extensively planted terraces of the Hanging Gardens.

More specifically and recognizably as green roofs, vegetation on roofs in ancient times probably resembled sod roofs such as those that exist in Scandinavia to this day. Sod roofs in Scandinavia existed before recorded history, and they are believed to have been a dominant roofing technology during Viking and Middle Ages., Sod roofs were an ideal choice for log cabins because the relatively heavy load of approximately 50 pounds per square foot helped compress the logs and make them more draft proof. Layers of birch bark underneath the sod provided waterproofing, while the sod itself provided efficient insulation from the cold.

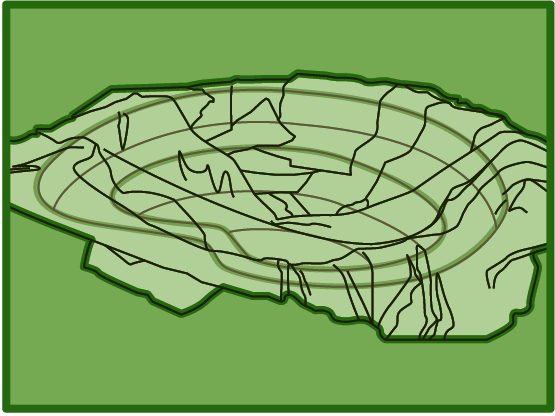

Image

An illustrative drawing of a green roof showing the developmental stages of the vegetation.

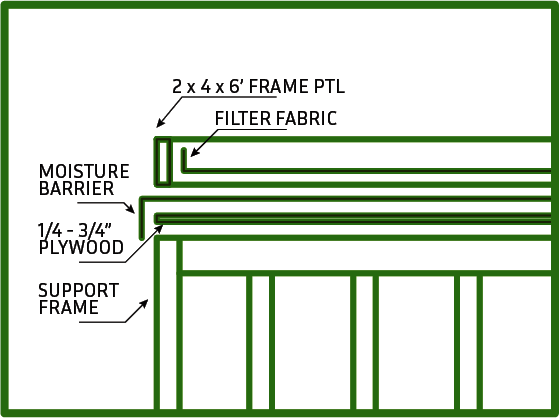

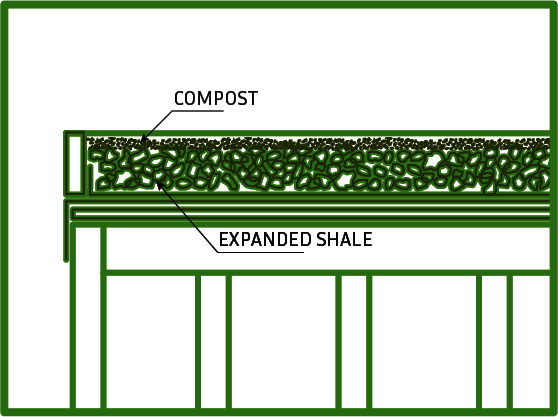

Image

"Green Roofs! Green Walls!! What Will They Think of Next?!"

The layers of the green roof are assembled with the support of a (1) structural frame, (2) plywood to provide a flat surface and rigidity, (3) moisture barrier, such as a butyl rubber liner, (4) geotextile filter fabric, and (5) a frame to hold soil and plants. The planting substrate consists of a (1) porous aggregate mixed with (2) compost. Using seed is an economically viable option and it allows plants to adapt to the environmental conditions from the beginning. Plugs and cuttings are another great choice as they provide a more instant effect. Mixing seeds and plugs is also a good way to diversify.

Image

Green Roof in Gano Park.

Planted in the fall of the previous year, this green roof at a local community garden was in flower by May, 2021.

Making a Meadow, Reimagining the American Dream

Our obsession with the lawn. The lawn holds so much symbolism, history and meaning in American culture that we may actually never see it completely disappear from our landscape’s vernacular. On the contrary, along with globalization in general, our influence on the world has precipitated the spread of lawn use into other parts of the globe, including Europe, South America, Far East Asia, and even Africa. There is a lot of debate and disagreement over whether lawns are actually beneficial or detrimental to the environment because collecting data on them has been a challenge. Depending on the maintenance paradigms, such as frequency of mowing, some lawns may contain a greater diversity of plants than others and thereby support more diversity of animals and insects, while others may be the complete opposite. Whatever the debate, it seems that lawns are here to stay. After all, more people engage directly with lawns than any other vegetative aspect of the landscape. Despite the existence of many lawns for purely aesthetic purposes, many are used for a variety of activities and functions from playing sports to providing vegetative buffers along highways that absorb stormwater runoff and pollution. While a sport like golf is completely reliant on turf, imagine sunbathing on a summer’s day in a park on a bed of gravel or a wooden platform, or worse yet, on a paved surface. As described in Part 3, Chapter 1, it is possible to cultivate and maintain a lawn organically (note, that organic does not necessarily mean sustainable), however, the mowing practice that is required to keep the lawns green year-round, is what makes them unsustainable and furthermore, lacking diversity.

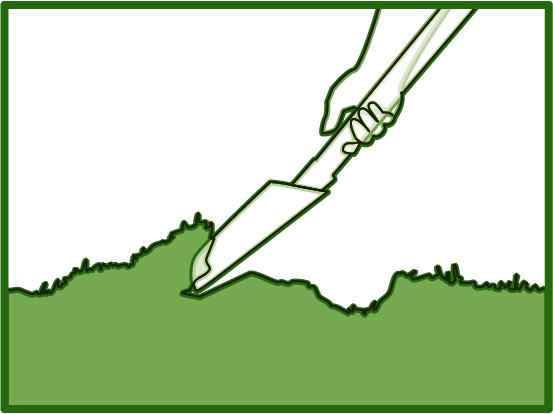

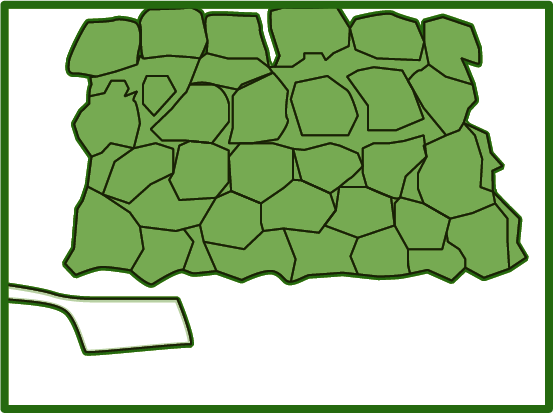

Image

An illustration of a meadow in the making shows [1] the removal of an existing front lawn, [2] the spreading of compost and [3] seeds, and [4] planting and watering of plant plugs.

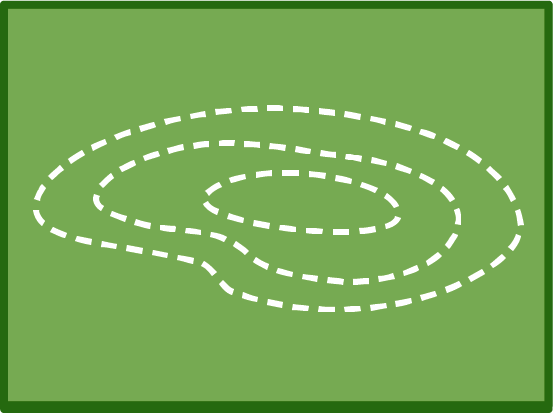

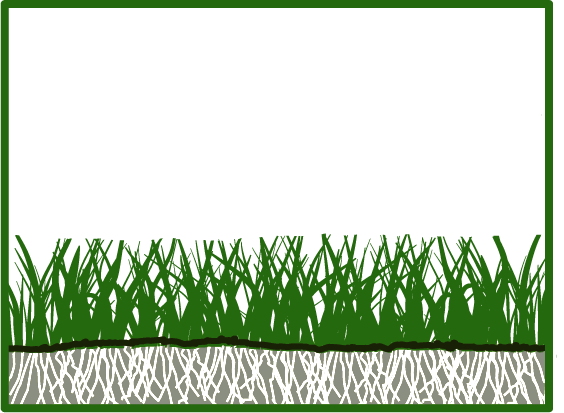

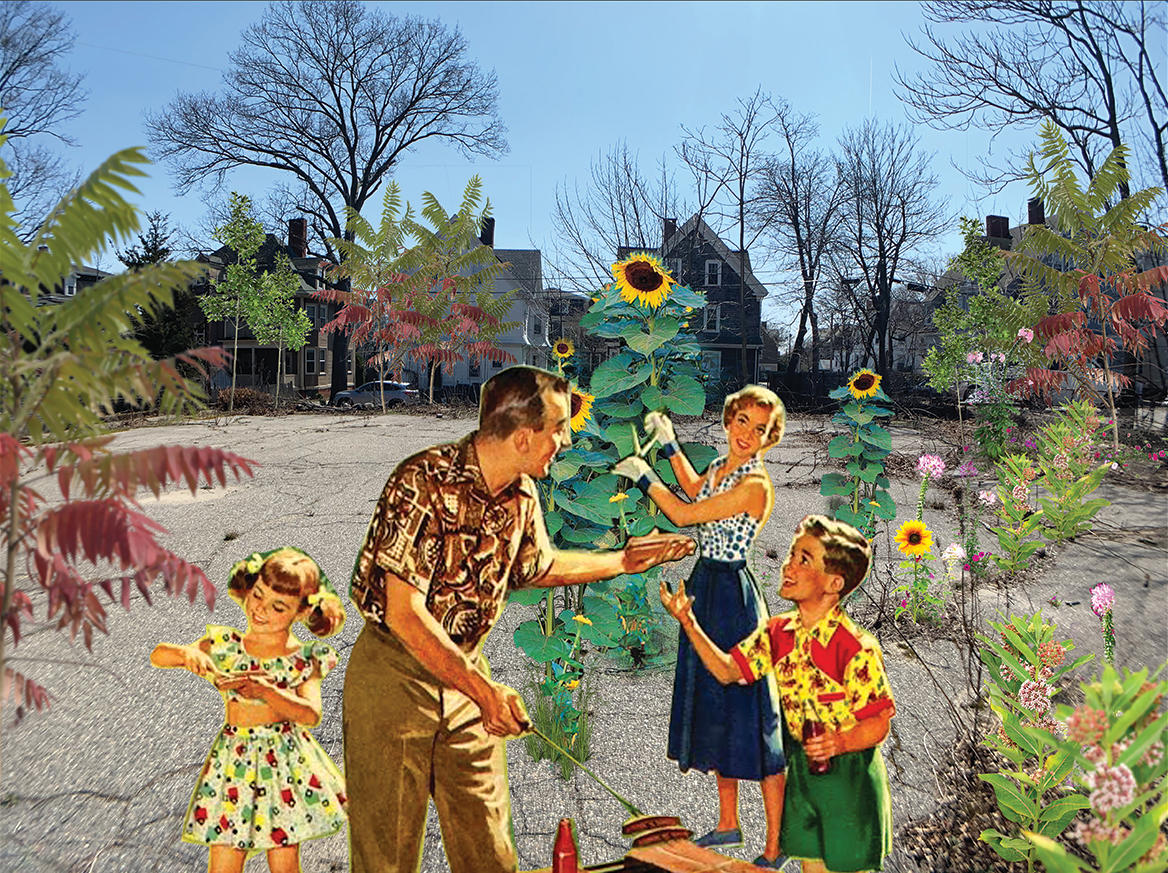

Image

"Reimagining the American Dream."

Lawn to Meadow making begins with [1] the removal of the sod. Typical grass species used in lawns are running varieties that spread through underground roots and stems. Grass can quickly out-compete other plants, especially if those are to be started from seed. [2] Sections of removed sod are laid upside down to (1) deter soil erosion caused by wind and water, (2) hold and release water, (3) keep soil cool, (3) slowly release nutrients back to the soil as the pieces decay and (4) reduce the need for disposal. [3] A compost dressing can be applied to further stimulate the soil biota and provide nutrients for newly introduced plants. Watering takes place before and after seeding to ensure good adhesion of the seeds to the surface of the soil and to jump start germination. [4] Watering plants is a practice of art, science and patience. A fine rosette head on a hose or watering can, (1) ensures that seeds, plant plugs and soil are not dislodged from place, and (2) that the water is able to percolate beyond the surface of the soil.

Image

A Meadow in Twelve Inches or Less.

Some ordinances in the United States do not allow lawns to exceed the height of 12 inches. This is a measure used to enforce the manicured lawn aesthetic based on the premise that unkempt front yards lead to a decrease in property values. However, growing a meadow lawn in less than 12 inches of height is possible through the reduction of mowing and fertilizing and stopping the use of herbicides. Flowering plants can then be allowed to spontaneously colonize or be intentionally introduced to the turf.

Meadow Lawn, Mowing towards a New American Dream

Maintaining a Meadow. It may seem counterintuitive to include the word “mowing” as an operative verb when referring to a pursuit of a dream not least because dreams are usually associated with growth rather than a stifling curtness, but also because in the preceding chapter mowing had been given a negative connotation on the account that continuous mowing of the lawn renders the practice of lawn keeping unsustainable. However, mowing itself isn’t necessarily a bad practice, especially if it is done on occasion. In fact, maintaining a meadow still requires periodic mowing to arrest succession. Most meadows are transitory, which means that sooner or later the herbaceous vegetation is superseded by woody shrubs and trees, in a process known as succession., Thus, mowing prevents woody plants from taking over. The mowing schedule somewhat depends on the plants being cultivated, when they emerge and when they perform their performance duties. Generally speaking, plants cultivated for flowers (and subsequent seeds) are organized into three categories: early season, mid season and late season blooming plants. Perhaps through eons of predation by herbivores, herbaceous plants have evolved to adapt to grazing by being able to regenerate their reproductive parts and thus still produce flowers and seeds. This adaptation is in large part due to the fact that these plants do not invest energy into wood production and therefore can recover quickly from grazing to set new shoots. In fact, grazing in some ways benefits plants as it encourages fuller, bushier growth. The absence of mammalian herbivores in urban settings, necessitates the use of mechanical ones, which is where the lawn mowers come in. Especially if a wide variety of flowering plants is being grown, with different blooming cycles and vigorous growth, a mid-season mow would benefit the plants rising up on the heels of the early bloomers. Typically, this should take place between late-June and early-July. In its first year, the meadow should be cut to about 8 inches in mid-season and then to about 6 inches in late fall, anytime after November. If the meadow is slow to start or is sparse, it should only be mowed in the fall.

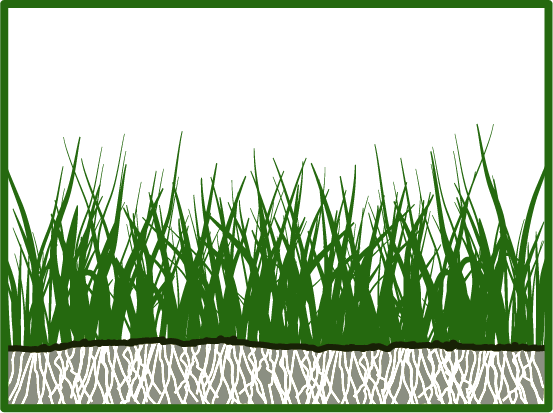

Image

Meadow Lawn, Mowing towards a New American Dream.

Image

[Collage caption]

A lawn can become converted to a lawn meadow or a "freedom lawn" by [1] suspending frequent mowing of the grass. [2] Suspending frequent mowing will enable grass to grow, as well as numerous plant seeds that are present in the soil bank. [3] Many so called weeds are actually wildflowers that serve a variety of ecological functions and provide unparalleled diversity. [4] Since beauty is in the eye of the beholder and function is a matter of personal awareness and opinion, the meadow lawn can be adjusted to exclude or include whichever species are sought after.

Image

An urban meadow, which was likely created through neglect and infrequent mowing, supports a diversity of plants and other living beings that rely on it.

Cultivating Freedom in the Pavement Cracks

Impervious surfaces, “Human beings around the world build, use and maintain constructed impervious surfaces for shelter, transportation and commerce. It is a universal phenomenon – akin to clothing – and represents one of the primary anthropogenic modifications of the environment. Expansion in population numbers and economies combined with the popular use of automobiles has lead to the sprawl of development and a wide proliferation of constructed impervious surfaces. The quantity of development that has occurred in recent decades is staggering. In the USA there are a million new homes and 16,000 kilometers of paved road built each year. The worldwide pattern of sprawl development will continue in the coming decades in response to both population growth and growth in living standards.”1 The above statement came from a study published in 2007, which assessed satellite imagery of impermeable surfaces from data sets compiled between 2000 and 2001.1 Systems that are embedded into the Earth’s crust, which include roads, buildings, driveways, sidewalks, parking lots and other manmade structures, allow us to subvert and control the forces of Nature. Through standardization, we have come to design and build very reliable ways of withstanding landscape flux; to provide safety from the elements and Nature. These solid, static structures are usually developed to be impermeable to withstand one of Nature’s most notorious corrosive forces — water. As a result, impervious surfaces are beginning to dominate our landscapes in ways that are extremely detrimental to our environment. Although dwellings and circulation infrastructure are on the list of impermeable surfaces, in this chapter we specifically consider the abandoned, derelict post-industrial and domestic sites and parking which feature paved over surfaces that may not be conducive to typical cultivation of biomass, particularly plants.

1 Christopher D Elvidge et al., “Global Distribution and Density of Constructed Impervious Surfaces,” Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) (Molecular Diversity Preservation International (MDPI), September 21, 2007), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3841857/#:~:text=We%20foun…)%20is%20constructed%20impervious%20surface.

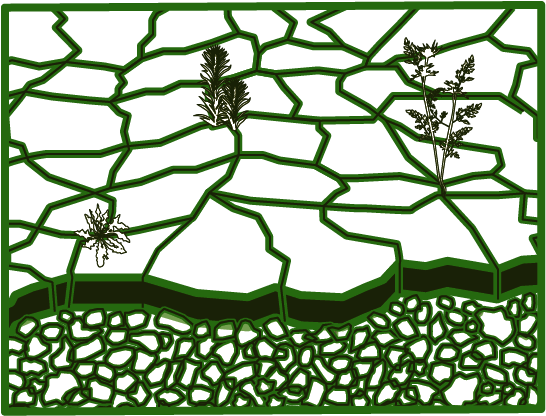

Image

Cultivating Crocodile Cracks.

Breaking down the barrier of old pavement between biomass and soil, allows living things to move freely, doing what they do best — thriving and diversifying, and perpetuating utopia.

Image

Cultivating Freedom in the Pavement Cracks.

Cracked pavement is an ideal space for plants that thrive in disturbed sites. [1] Crocodile cracking, a pattern illustrated below, occurs when pavement subgrade is compromised. The resulting cracks form interconnected networks through which water travels and provides opportunities for spontaneous vegetation. [2] Widening the cracks and gaps provides greater opportunities for plants to take root. A little physical intervention is all that's needed to help live colonize an otherwise abandoned and lifeless pavement. [3] If there is an interest to cultivate specific plants, it is best done with seed and occasional watering to get things started. [4] Which plants stay or go become a question of apparent aesthetics and functions, particularly for those plants whose virtues are yet to be discovered...

Image

[Photo caption]

AFTERWORD: Thesis Reflection

Opportunity for diversity, is diversity of opportunity.

“Nature must not win the game, but she cannot lose. And whenever the conscious mind clings to hard and fast concepts and gets caught in its own rules and regulations — as is unavoidable and of the essence of civilized consciousness — nature pops up with her inescapable demands.”— Carl Jung.

In the quote above, Carl Gustav Jung, “a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology,”1 is talking about the conscious and the unconscious mind, making a distinction that, while the conscious must rule over the decisions made through thought and reason, the unconscious will always yield its influence as it is the collective wisdom of the human species.2 Nature is similar in that it often defies the conscious ideologies of mankind but still serves as the collective wisdom of the living world. This notion is more than just a mere theoretical philosophy. The intrinsic value of the diversity of living things is found in their genetic makeup. The increased awareness of how anthropogenic activities impact the environment has prompted many people to explore new ways of approaching Nature, including embracing some of its spontaneous qualities allowing them to redefine aesthetic values based on their apparent benefits. But humans still hold Nature at an arm's length. For one, Nature continues to pose threats with its elements, various climate conditions and weather patterns. Another looming danger is from the animal species with which we share our world. Although large animals no longer pose a serious threat in large part due to extrication efforts, poaching and habitat loss, people in close contact with pockets of remaining wilderness still wage a battle with them, while city dwellers fight off mammals and birds that are associated with blight and disease. The smaller the species, the harder it is to isolate and maintain the threat that comes from it, as is the case with numerous insects, parasites, fungi, bacterias, and viruses. Humanity has had a very long relationship with diseases, pathogens and plagues. We have done a lot to try and eradicate everything that ails us and often with justifiable reason — the assurance of our own survival. As a result we often seek to assign values to living things whose existence we wish to justify, often on the perceived virtues of their aesthetic qualities or benefit values they provide to us. And yet we seldom question how we fit into this picture; how our own presence benefits the rest of the natural world. The point of this thesis is not necessarily to denounce or validate the reasons or efforts for controlling Nature. Instead the point is to bring about awareness of how we assign meanings and values, and how the actions we take on behalf of those meanings and values shape the world around us. Because, while meanings and values change over time, the actions that are taken, especially those that severely impact the existence of living beings, are often damaging and irreversible. As the dominating species, which prides itself on awareness and intellect, it behooves us, humans, to recognize the great impacts we have on our planet and all of its inhabitants when we make wholesale decisions which decide who gets to occupy space and who doesn’t, who gets a share of the resources and who doesn’t, and who gets to live and who doesn’t. Additionally, it is imperative that we start addressing uncomfortable questions that pertain to the unbridled expansion and resource extraction of our species, including overpopulation and encroachment onto the last bits of wilderness. This is especially crucial in the face of the ongoing Sixth Mass Extinction event, where we are forever losing an immense amount of genetic diversity, the likes of which have previously been the result of occurrences not originating on our planet. Care for humanity cannot outweigh the care for other living beings because we have not evolved separately from the systems that we are connected to; the same systems that sustain us. The systems that sustain us are regenerative, unlike the synthetic mechanized technologies that we create, which require resources that are often finite or unsafe. While we can no longer imagine life without some of those technologies, such as computers, they are destined for obsolescence because they are not living and thus unable to evolve. And although living systems are regenerative, they are not immune to succumbing to great pressures of anthropogenic activities, which often preference human needs. It is also imperative to recognize diversity within our own species and use the powers that placed us at the apex of the natural world to make better decisions that promote greater equity and justice throughout the human race.

1 “Carl Jung,” Wikipedia (Wikimedia Foundation, May 11, 2021), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Jung.

2 Andy Newman, “Subway Mosaic Turns Riders Into Underground Philosophers,” The New York Times (The New York Times, December 27, 2004), https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/27/nyregion/subway-mosaic-turns-riders-….

Image

Come sit and ponder with me the existential questions of our day, while we bear witness the vigor and virility of our verdant world.

BIBILOGRAPHY

- Ignatieva, Maria, et al., “Lawn as a Cultural and Ecological Phenomenon: A Conceptual Framework for Transdisciplinary Research,” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14, no. 2 (2015): pp. 383-387, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.04.003.

- Jacobs Karrie. “The High Line Network Tackles Gentrification.” Architect, October 16, 2017. https://www.architectmagazine.com/design/ the-high-line-network-tackles-gentrification_o.

- James Corner Field Operations, Diller, Scofidio + Renfo. The High Line: Foreseen, Unforeseen. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2015.

- Jenkins, Virginia Scott. The Lawn: a History of an American Obsession. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999.

- Kostromytska, Olga S. “Annual Bluegrass Weevil Cross-Resistance to Insecticides.” Golf Course Magazine: Powered by GCSAA, January 1, 2019. https:// www.gcmonline.com/course/environment/news/ abw-insecticide-resistance.

- “Landscape IPM.” History of IPM “ Landscape IPM. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://landscapeipm.tamu.edu/ what-is-ipm/history-of-ipm/#:~:text=Dr.,Dr.

- “Landscaping and Construction Material Weights.” Harmony Sand & Gravel. Accessed May 9, 2021. https:// harmonysandgravel.com/material-weights.

- Land, Leslie, et al. The New York Times 1000 Gardening Questions & Answers: Based on the New York Times Column ‘Garden Q. & A'. New York: Workman Pub., 2003

- Matthews, Karen. “New York’s High Line Park Marks 10 Years of Transformation.” ABC News. ABC News Network, June 9, 2019. https://abcnews.go.com/Lifestyle/wire- Story/yorks-high-line-park-marks-10-years-transformation- 63587235.

- Marshall, Michael, “Scattering Moss Can Restore Key Carbon Sink,” New Scientist, September 27, 2012, https://www.newscientist.com/article/ dn22313-scattering-moss-can-restore-key-carbon-sink/.

- “Meadow,” Wikipedia (Wikimedia Foundation, March 20, 2021), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meadow.

- Newman, Andy. “Subway Mosaic Turns Riders Into Underground Philosophers.” The New York Times. The New York Times, December 27, 2004. https://www.nytimes. com/2004/12/27/nyregion/subway-mosaic-turnsriders- into-underground-philosophers.html.

- The New Oxford American Dictionary. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Old Farmer’s Almanac. “What Are Plant Hardiness Zones?” Old Farmer’s Almanac. Accessed May 2, 2021. https://www.almanac.com/content/ plant-hardiness-zones.

- “Poa Pratensis,” Wikipedia (Wikimedia Foundation, April 6, 2021), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poa_pratensis.

- Piepenburg, Erik. “Under the High Line, a Gay Past.” The New York Times. The New York Times, February 3, 2012. https://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/03/ under-the-high-line-a-gay-past/.

- “Range Plants of Utah,” Kentucky Bluegrass (Utah State University Extension), accessed May 12, 2021, https:// extension.usu.edu/rangeplants/grasses-and-grasslikes/ kentucky-bluegrass.

- Rhodes, Christopher J. “The Imperative for Regenerative Agriculture.” Science Progress 100, no. 1 (2017): 80–129. https://doi.org/10.3184/00368501 7x14876775256165.

- Ruzickova, Helena, Bural, Miroslav, “Grasslands of the East Carpathian Biosphere Reserve in Slovakia,” In: Office of Central Europe and Eurasia National Research Council, Biodiversity Conservation in Transboundary Protected Areas, National Academies Press, Sept 27, 1996, p. 233-236, as cited by Wikipedia, https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meadow

- Seiter, David, McPhearson, Timon. Spontaneous Urban Plants: Weeds in NYC. Archer, 2016.

- Seiter, David. “2015 ASLA Professional Awards.” Spontaneous Urban Plants | 2015 ASLA Professional Awards, 2015. https://www.asla.org/2015awards/96909. html.

- “The State of Regenerative Agriculture: Growing With Room to Grow More.” Conservation Finance Network, March 24, 2020. https://conservationfinancenetwork. org/2020/03/24/the-state-of-regenerative-agriculture- growing-with-room-to-grow-more.

- Stewart, B. A., Howell, Terry A. Encyclopedia of Water Science. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2003. Spinney, Laura. “Panicking about societal collapse? Plunder the bookshelves”. Nature. 578 (7795).

- Stewart, B. A., and Terry A. Howell. Encyclopedia of Water Science. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2003.

- “Tree Choices - Urban Forestry News and Views.” Accessed May 3, 2021. https://juneautrees.files.wordpress. com/2008/01/natives_vs_nonnatives-or-09.pdf.

- Velazquez, Aramis. “New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) Announces Sustainable Roof Requirements for New Buildings Go Into Effect.” Greenroofs.com, November 16, 2019. https://www. greenroofs.com/2019/11/16/new-york-city-departmentof- buildings-dob-announces-sustainable-roof-requirements- for-new-buildings-go-into-effect/.

- Wallander, Hokan, et al., “Production, Standing Biomass and Natural Abundance of 15 N and 13 C in Ectomycorrhizal Mycelia Collected at Different Soil Depths in Two Forest Types,” Oecologia 139, no. 1 (January 2004): pp. 89-97, https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00442-003-1477-z.

- “Welcome to the Biological Control Site.” Biological Control : A Guide to Natural Enemies in North America. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://biocontrol.entomology. cornell.edu/index.php.