Email: yliu09@risd.edu

ABSTRACT

Climate change is posing great challenges to Tuvalu, a small archipelago in the center of the Pacific Ocean. With low elevations above sea level, poor soil, and limited land resources, Tuvalu is considered to be one of the smallest countries in the world, as well as the most vulnerable nation under climate change. About 2000 years ago the seafaring Pacific Islanders inhabited the archipelago and developed its unique culture following the fluid geographies of atoll islands––a culture that was once associated with the notion of paradise, and which gradually faded away with the arrival of western colonizers in the 19th century.

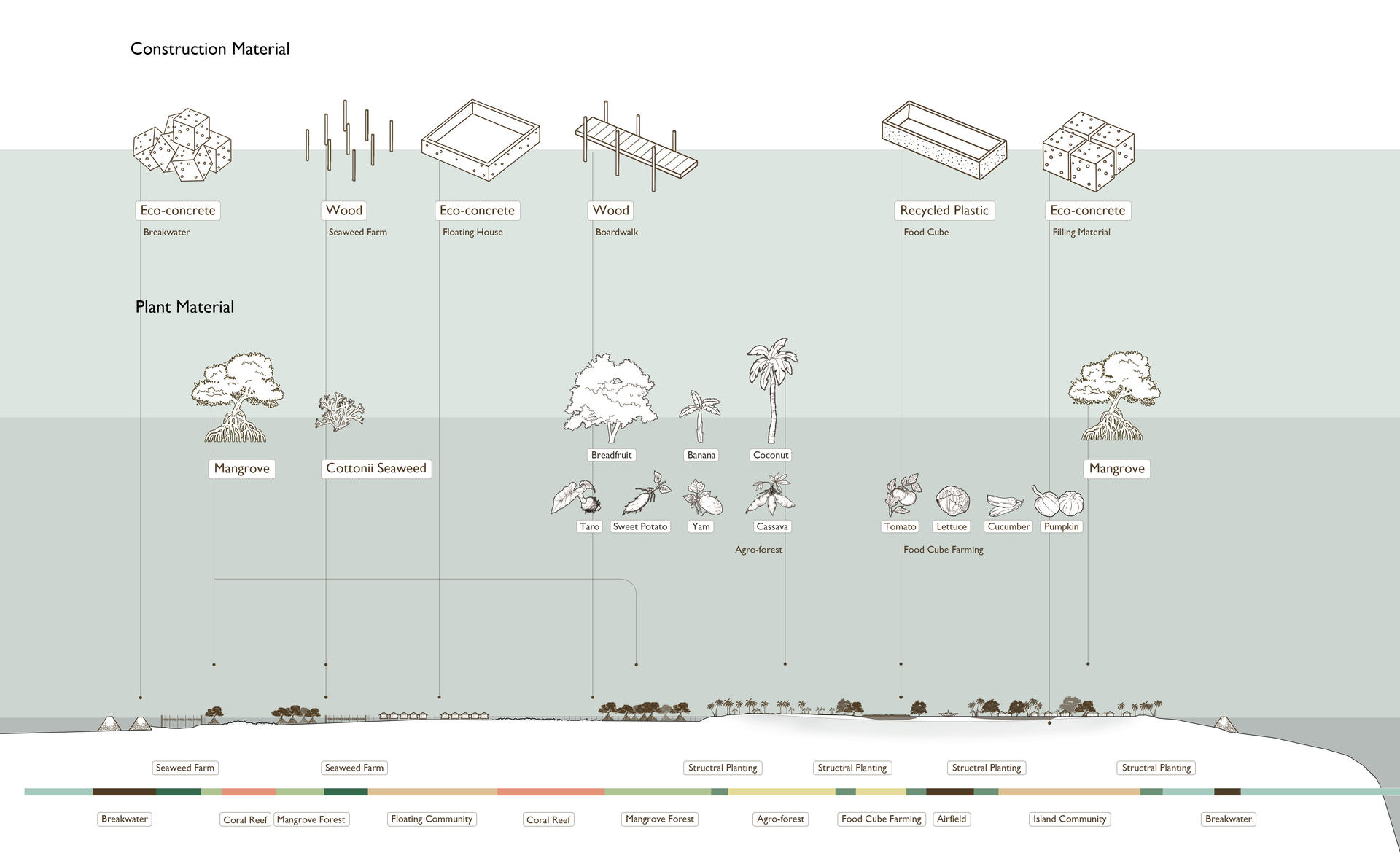

This thesis focuses on the study of the indigenous culture of Tuvalu to then explore a design approach for a new floating landscape. The new landscape adopts a regressive strategy that expands into the inside of the atoll and involves a flexible and constantly evolving aquaculture-floating habitation development in the lagoon of Funafuti, the capital island of Tuvalu. In the process, a new type of concrete material made with plastic as an aggregate is proposed as a solution to face sea level rise whilst also addressing, even if only partially, the issues related to abundant plastic pollution on the island.

Speculating on different scenarios spreading over the course of fifty years, the design experiments with a series of land and water-based ideas where flexibility becomes a key concept. The thesis ultimately aims to open up questions about the role of landscape architecture in supporting and mediating change in territories and their communities that currently face serious and existential pressures from climate change, or soon will.

Fluid Lifestyle

Image

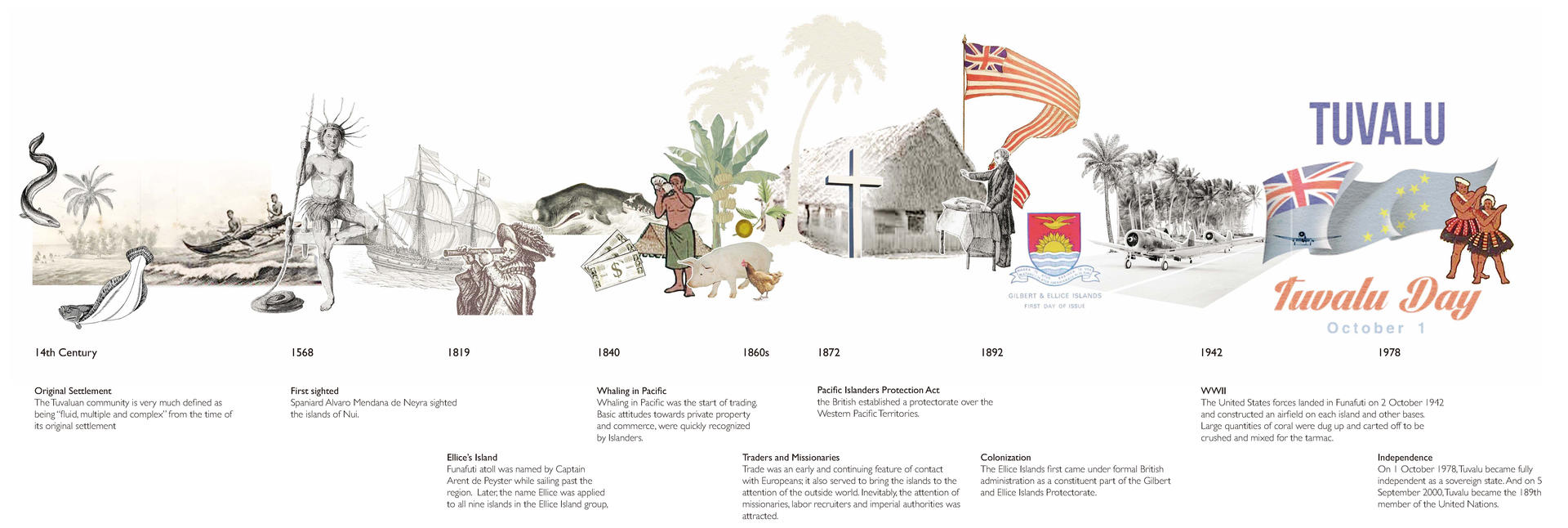

Indigenous Culture of Tuvalu

The Tuvaluan community is very much defined as being “fluid, multiple, and complex” from the time of its original settlement in the 14th century. In order to adapt to the dynamic and fluid nature of atoll islands, local communities lived with a nomadic lifestyle, moving back and forth between villages to let the coconut and fish grow. Meanwhile, they also never stopped searching for new islands in the ocean.

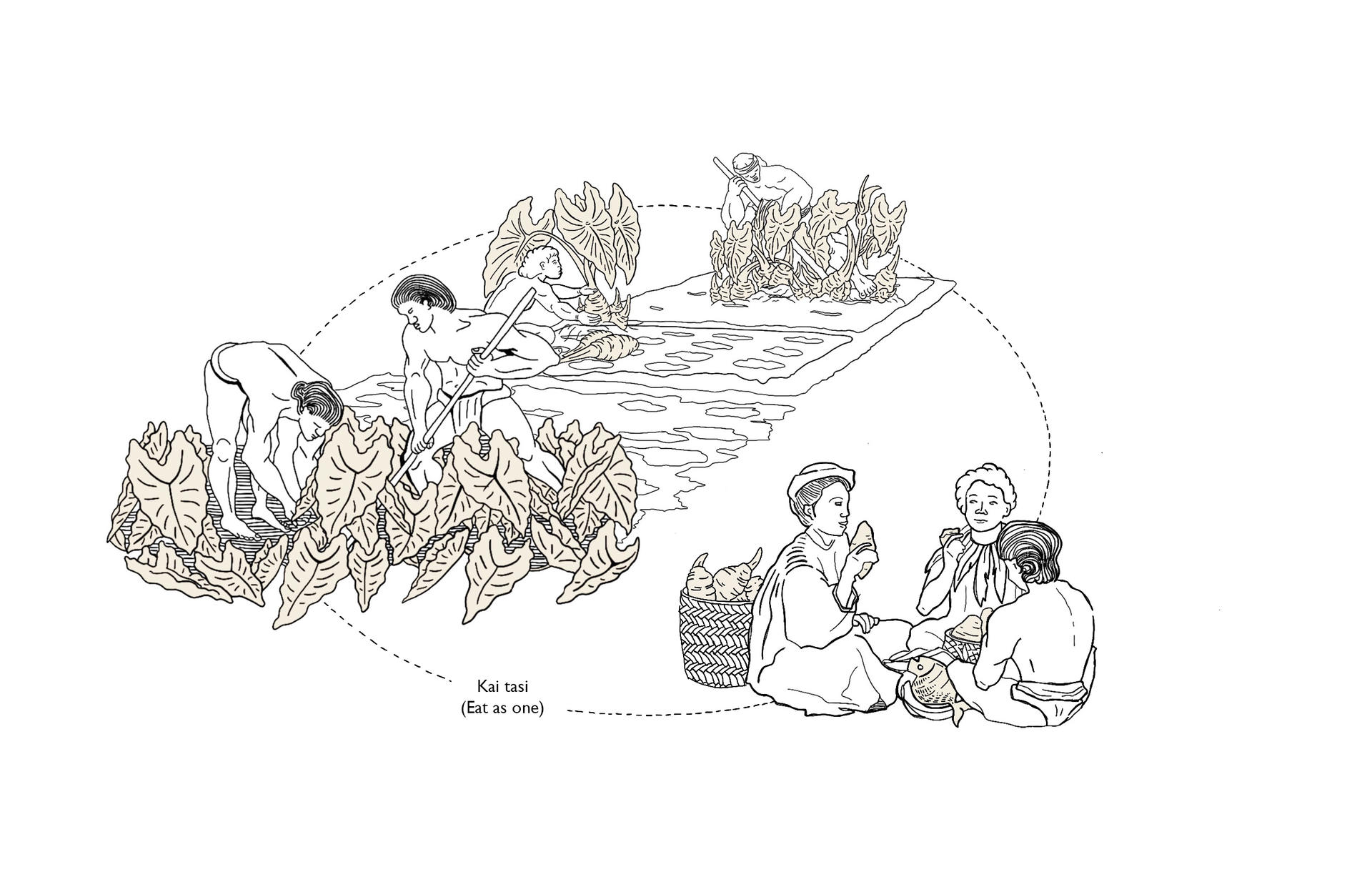

Collectivity was also an important part of their traditional lifestyle. Ideally, a single land unit was collectively owned and worked by the members of a puikaainga (‘landholding group’) under a form of tenure known as Kai tasi (‘eat as one’); In practice, however, land-holding units were usually smaller than this and cut across puikaainga boundaries. The produce of the land, the fruits of fishing practice, or any goods received through ceremonial presentation or exchange, were distributed among the households according to status and need.

Tradition of Kai tasi

Image

Timeline of Tuvalu

Image

The Arrival of Western Culture

However, the mobility of all atoll-dwellers and their traditional land tenureship was interrupted by the arrival of the cash economy, a new religion, as well as British colonization in the 19th century. The coming of western cultures introduced the concept of fixed property, which superseded Tuvalu’s original fluid lifestyle later on. Colonizers settled all the villages and even banned islanders from traveling between atolls for easier management.

Image

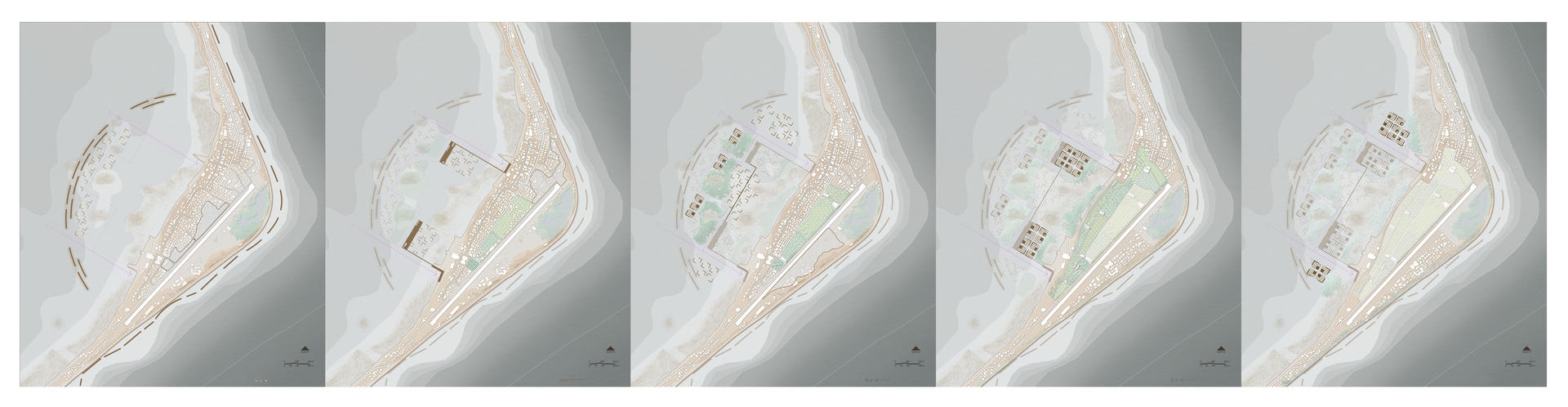

0-50 Years Plans

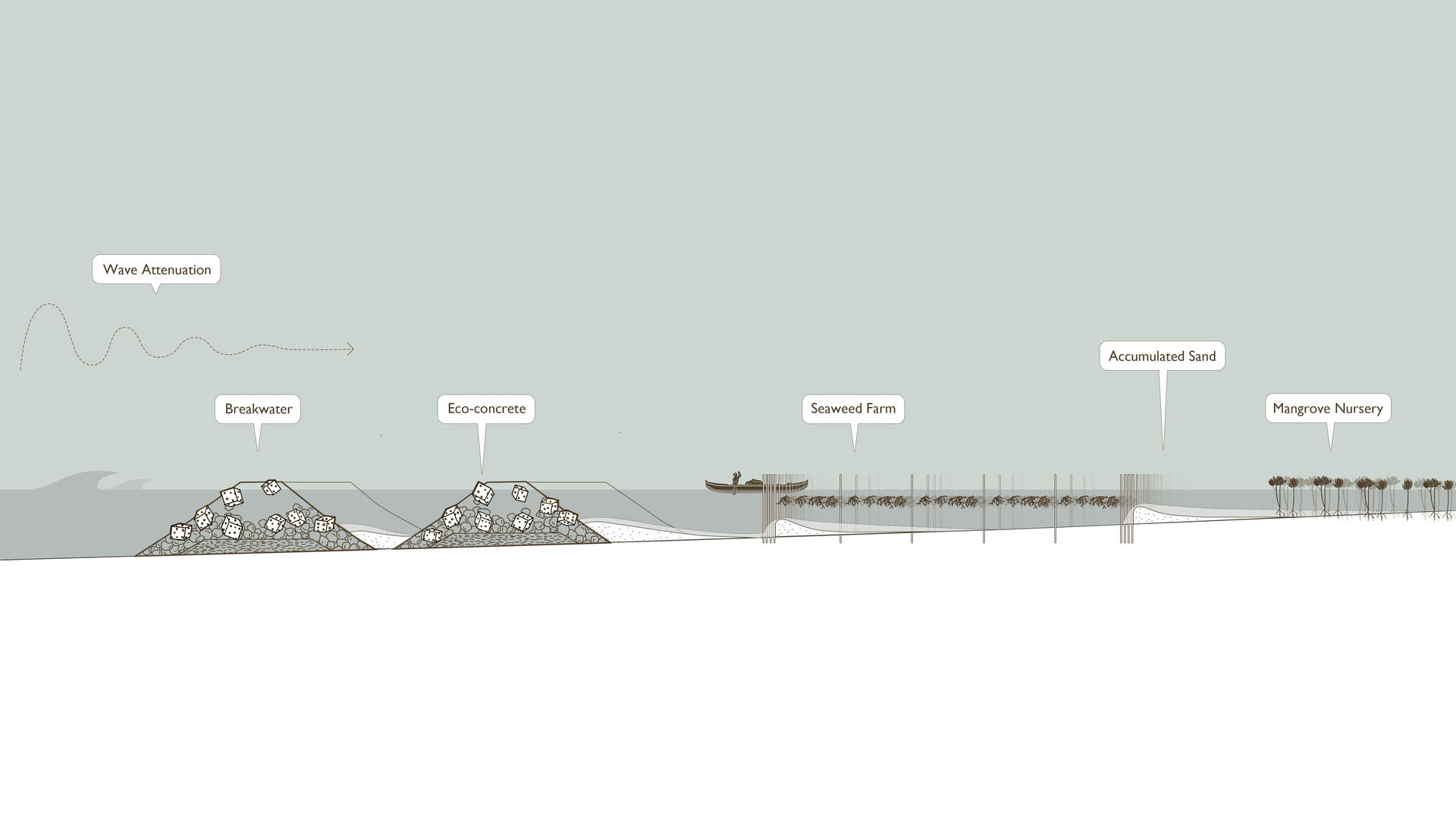

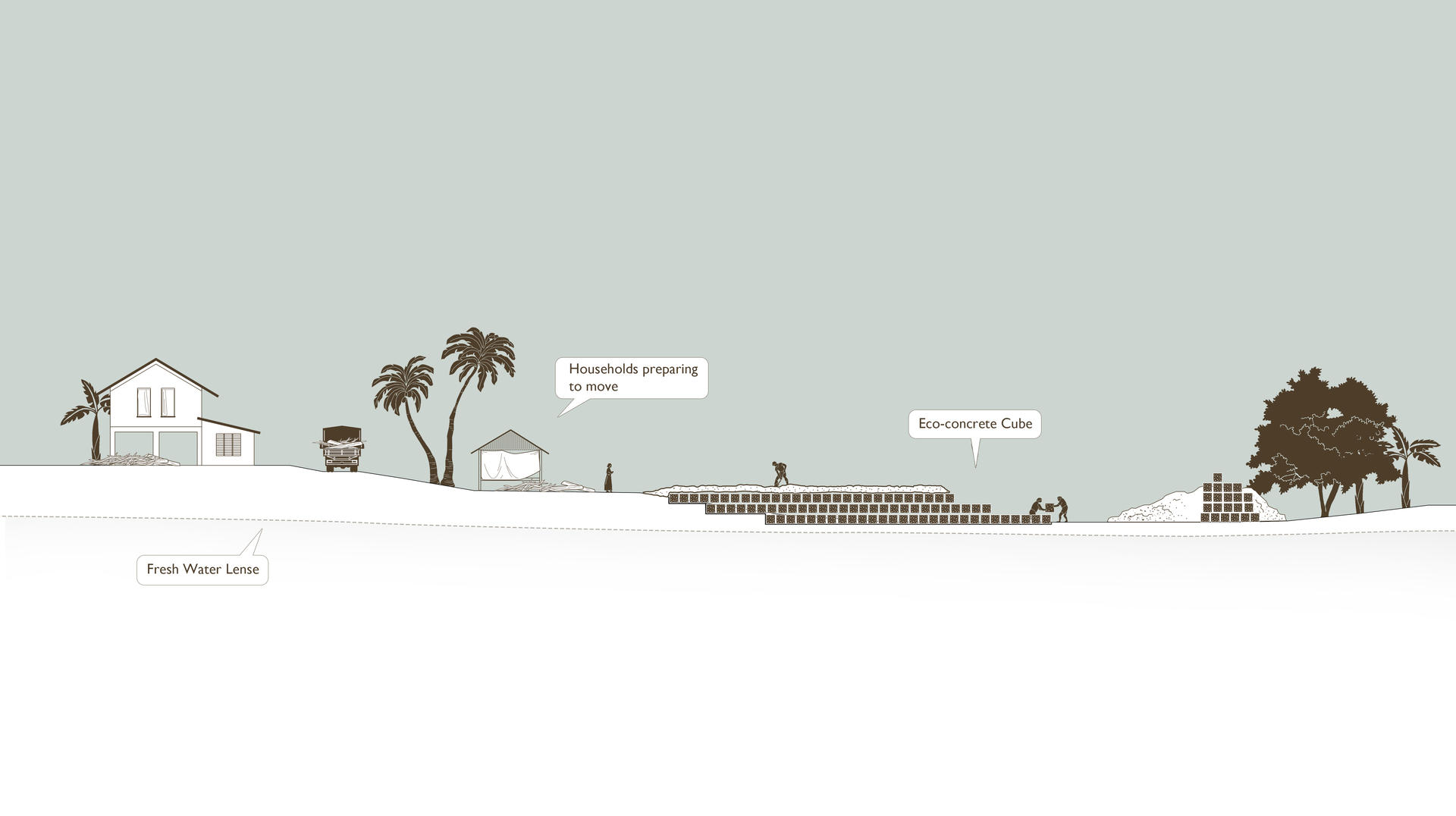

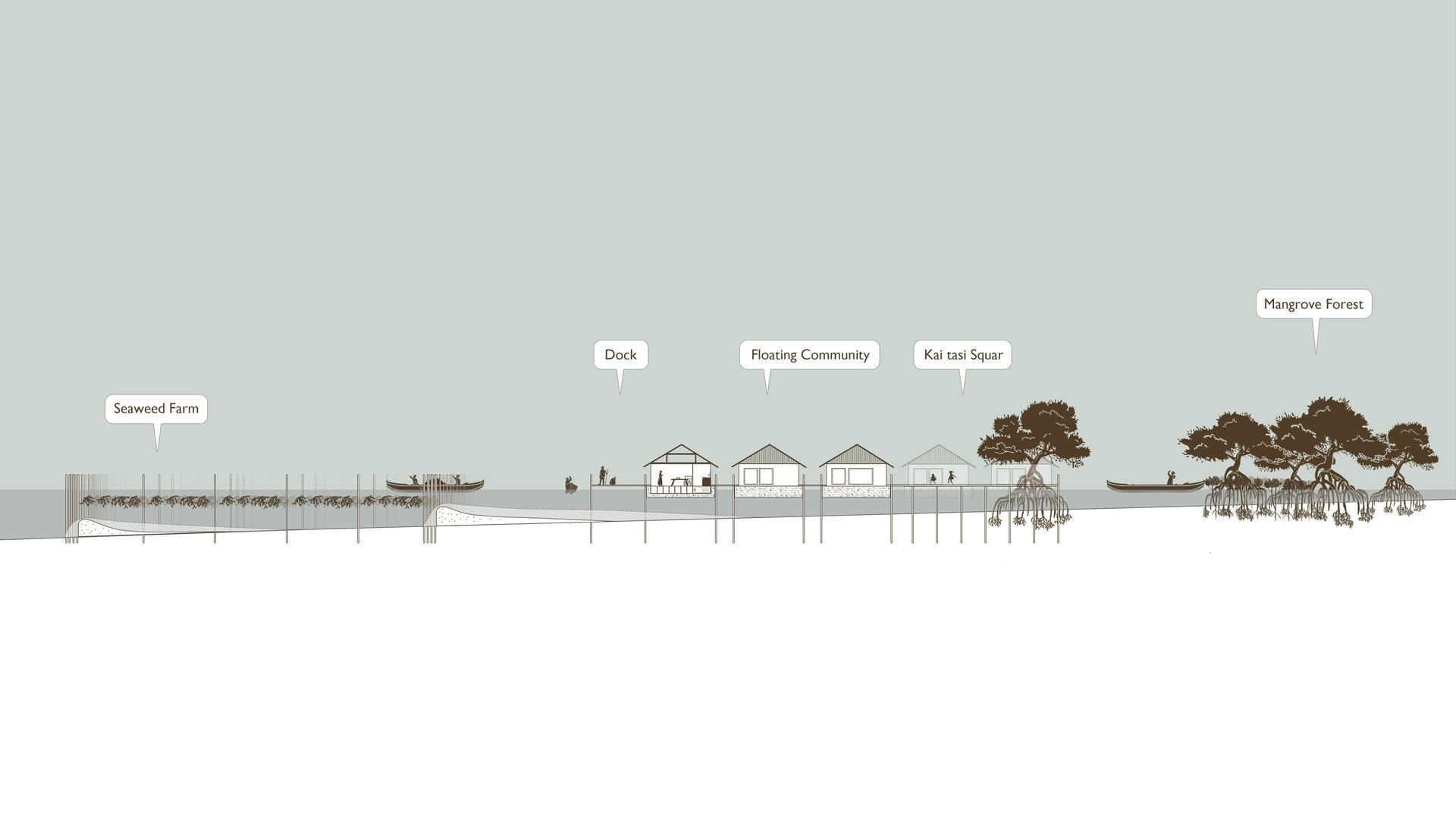

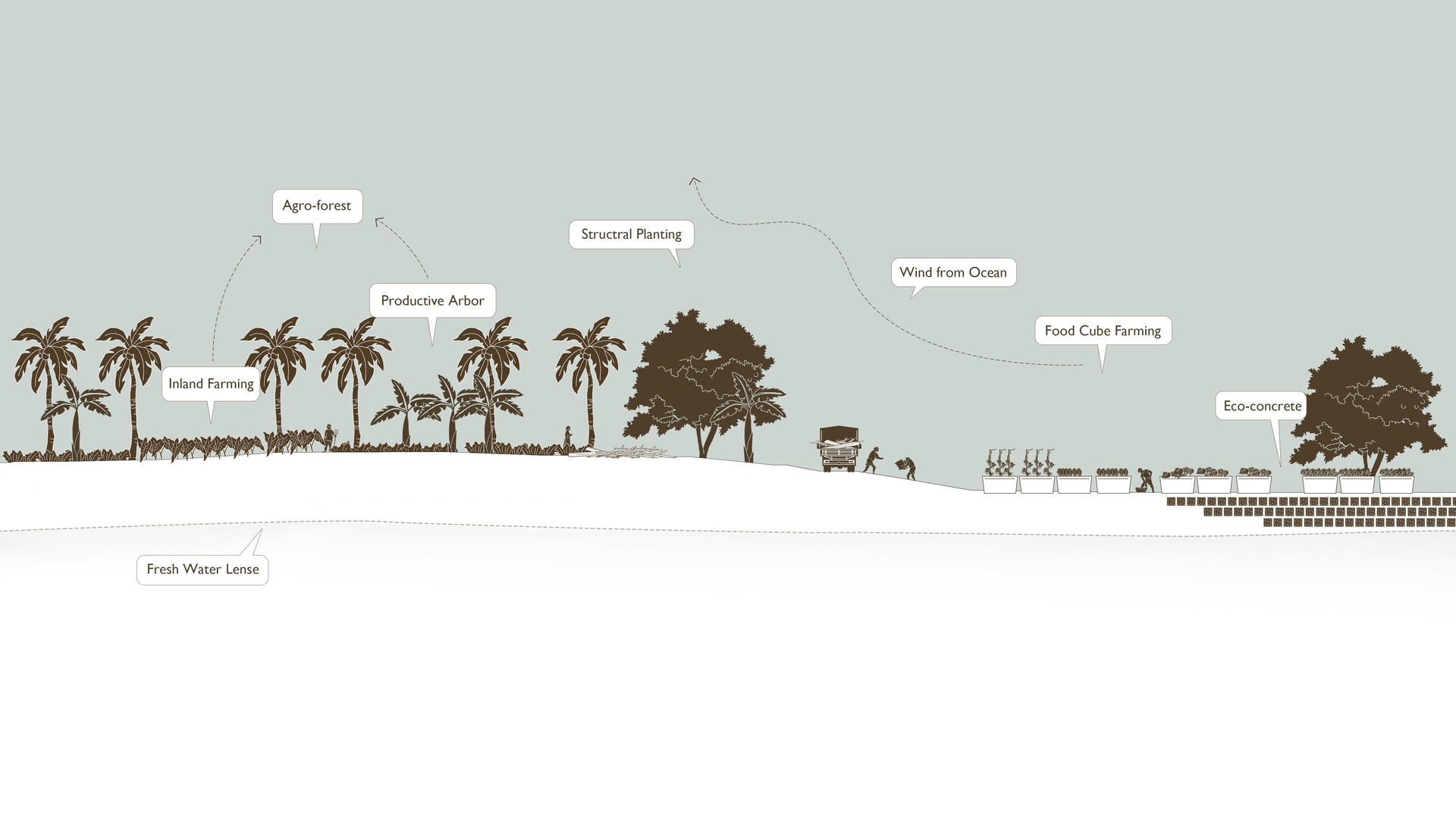

The new landscape adopts a regressive strategy that expands into the inside of the atoll and involves a flexible and constantly evolving aquaculture-floating habitation development in the lagoon of Funafuti, the capital island of Tuvalu.

In the lagoon, the system started with the artificial reef and seaweed farms. As more sand accumulates, it creates a suitable habitat for mangrove forests. Seaweed farms will be gradually turned into floating villages as the system develops further in time. On the island, areas with lower elevations will be elevated with eco concrete and become the location of new settlements. The highland will then be turned into farming areas, with structural planting on both sides to work as wind protection.

Image

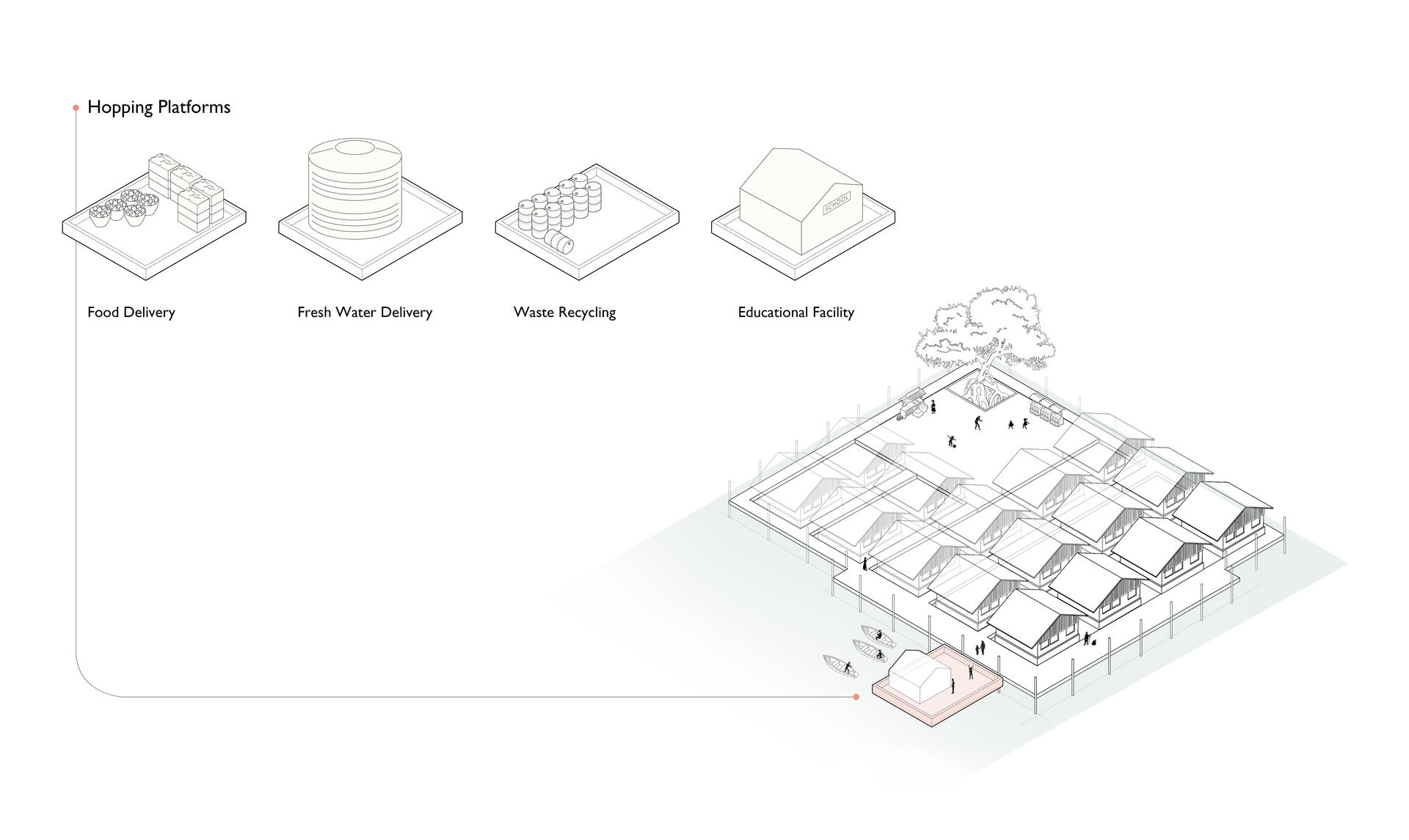

Hopping Platforms

The hopping platform system is an approach to increase the adaptation of the floating communities. Platforms with the functions of food delivery, fresh water delivery, waste recycling, and educational facilities can be attached to the wooden docks of different floating communities according to needs.

Image

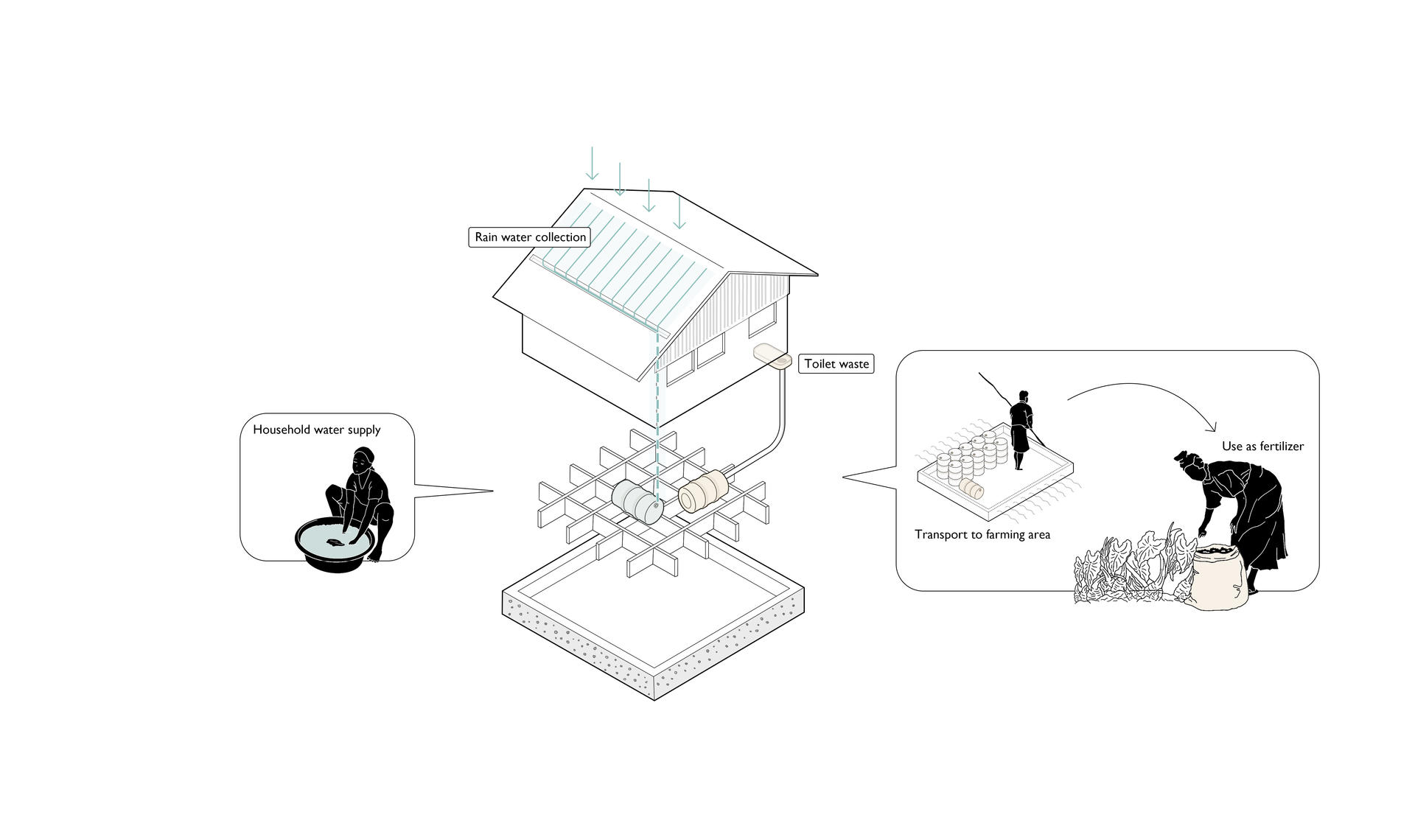

Sustainable Design

A single floating house can be separated into three layers, the concrete hull, collection layer, dwelling space, and roof. Water and waste are collected and recycled to the maximum extent. Plastic waste is exported to other countries in the production of eco-concrete. While organic waste is transported to the island and used as fertilizer.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

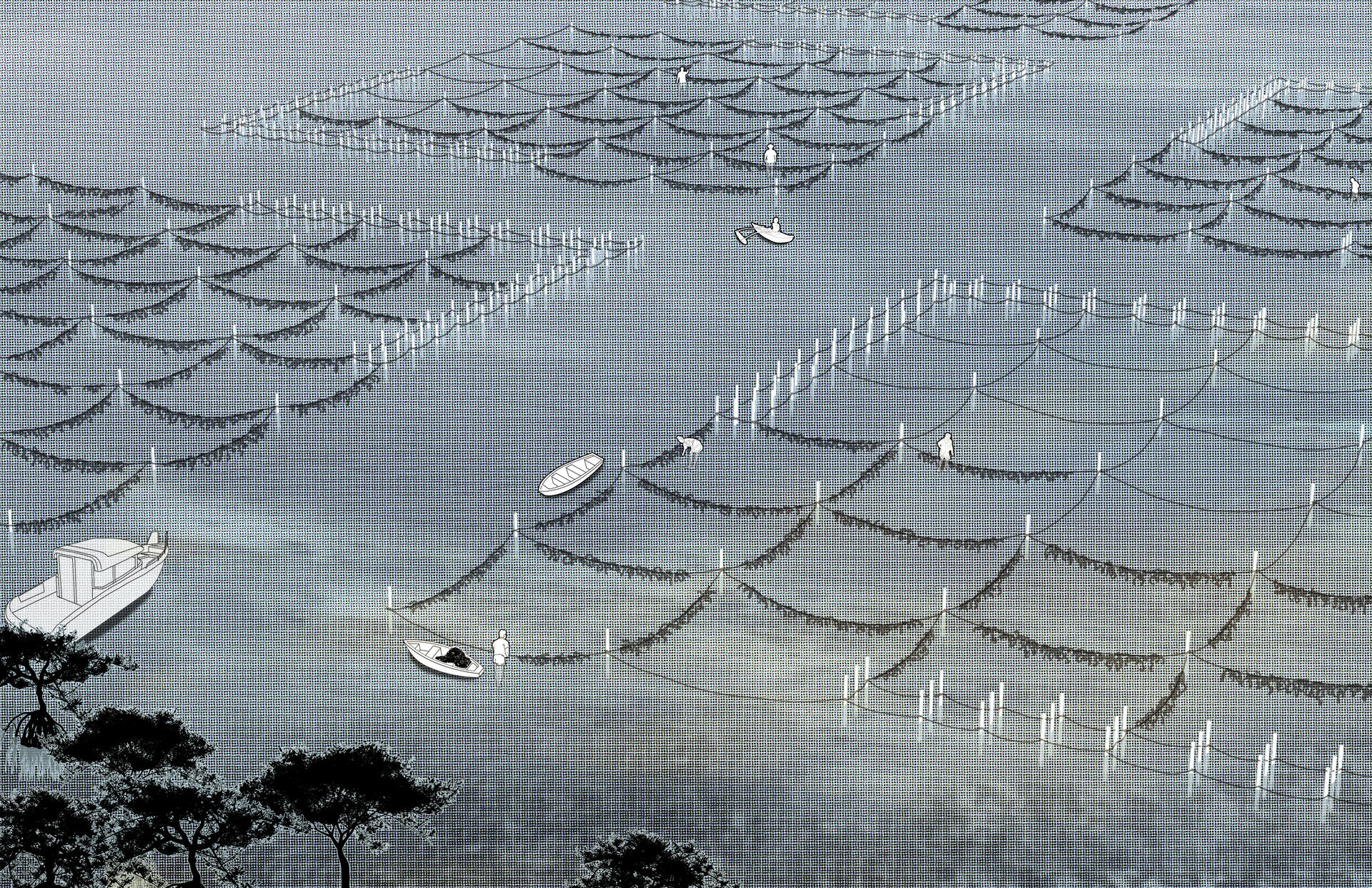

Seaweed Farms

The people of Tuvalu lived a completely self-sufficient life in the past. Only with the arrival of the cash economy in the 19th century did people begin to trade with the outside world. But this change also brought problems like overfishing and unsustainable farming that caused huge damage to the environment. So a combination of both subsistence and cash economy is developed in the thesis. Seaweed farming is an aquaculture practice with great economic value. Meanwhile, seaweed is also a major component of sustainable development with the creation of seaweed biomass and fertilizer.

Image

Floating Communities

As the seaweed farm continues to develop towards the coastline, enough sediments are accumulated by the wooden stakes of the farming areas, and suitable habitat for mangrove forest is created. A few years later, floating villages are developed following the grid set up by the seaweed farming blocks, welcoming the relocation of the first group of seaweed farmers.