ABSTRACT

This thesis explored the idea of interdisciplinary study between film media and landscape architecture. Through the study of film theory in narrative and cinematography, and experimentation with multi-medium, in order to discover the contribution of media study and film theory in landscape architecture, and further explored a way to drive and reshape the perception and focus of humans’ experience in landscape, in order to develop a new typology of performative space with filmic experience.

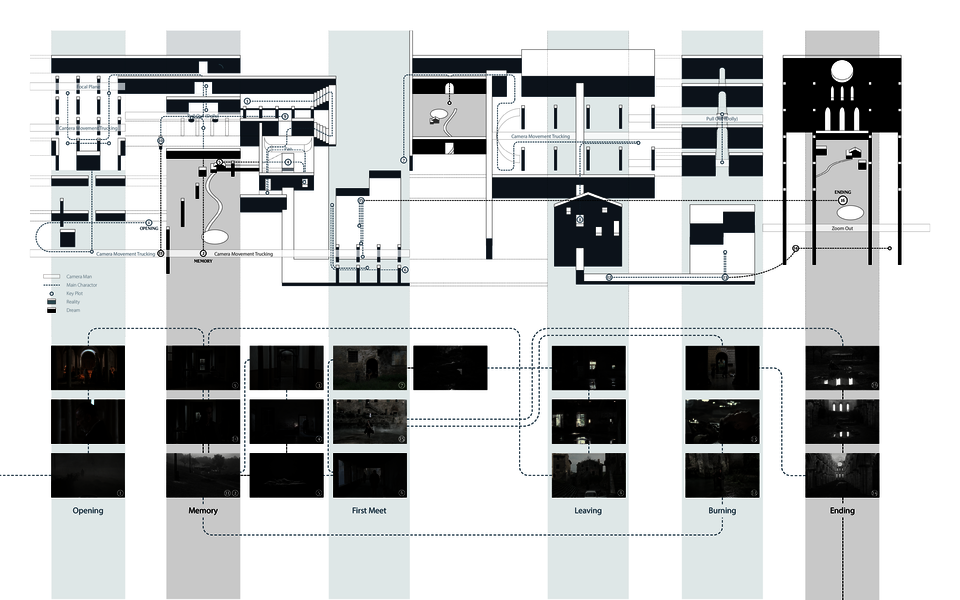

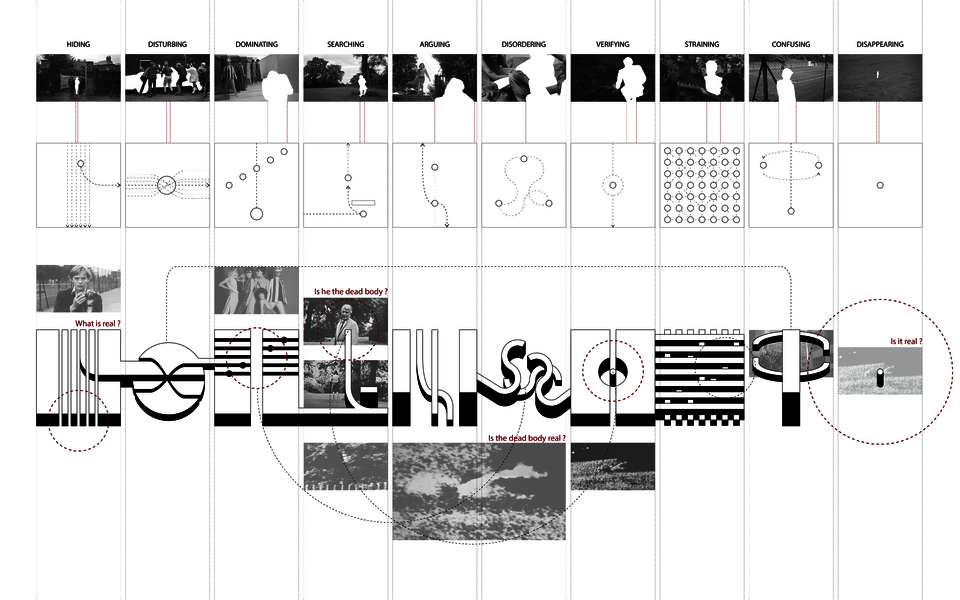

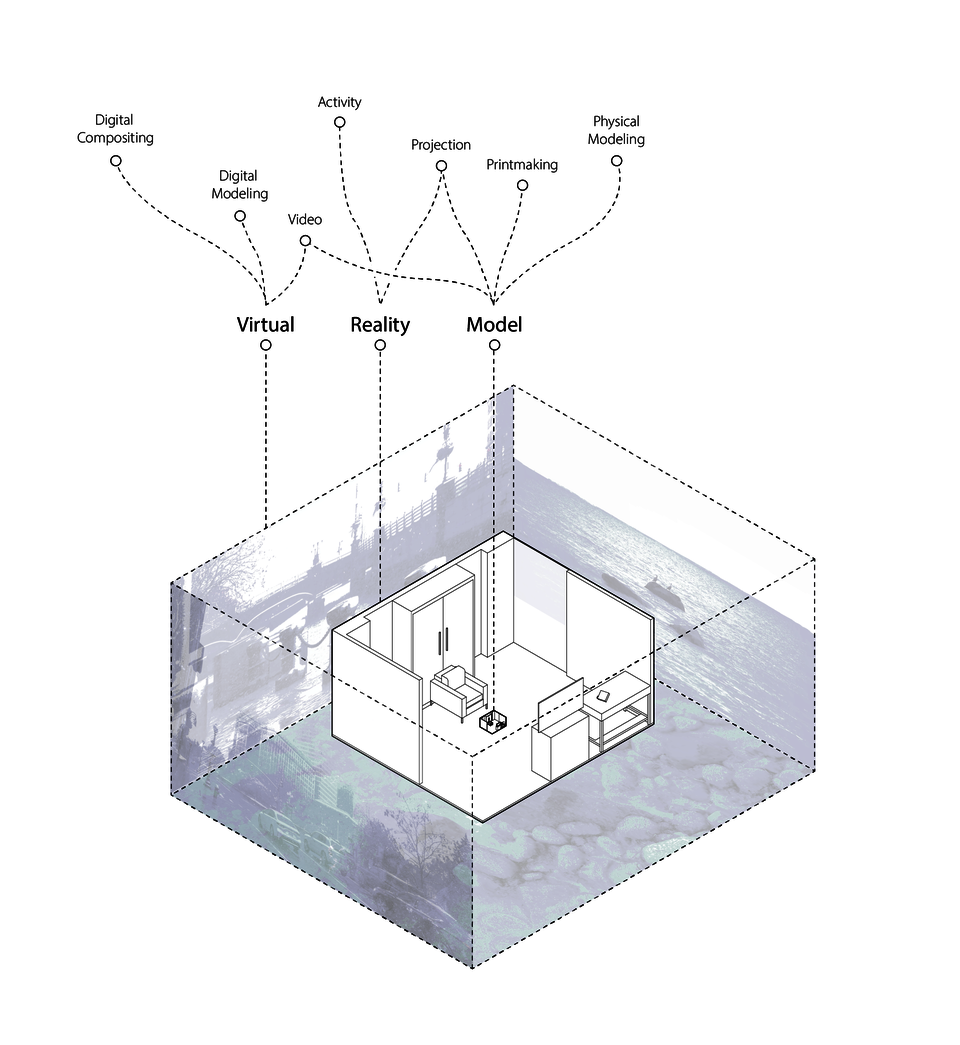

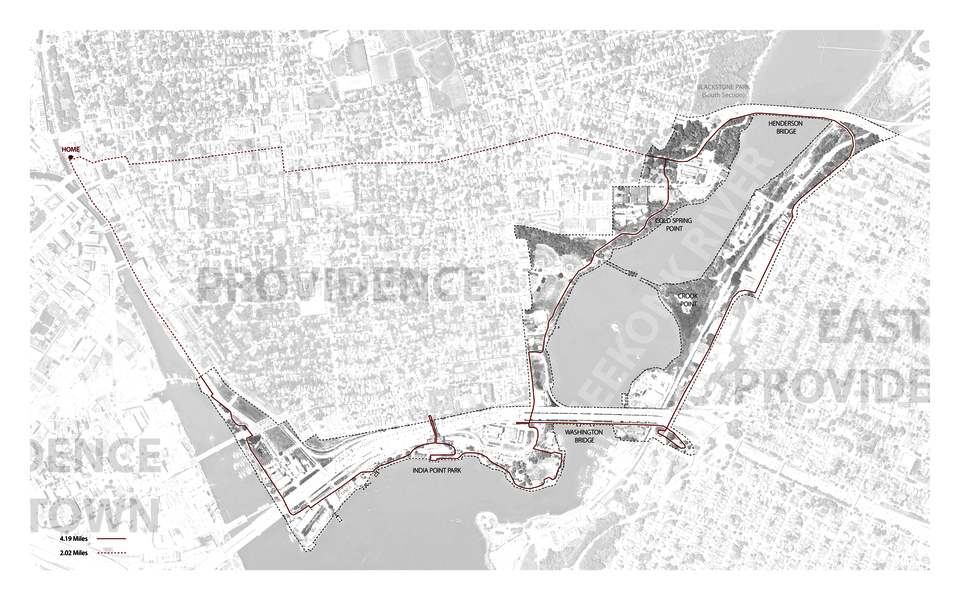

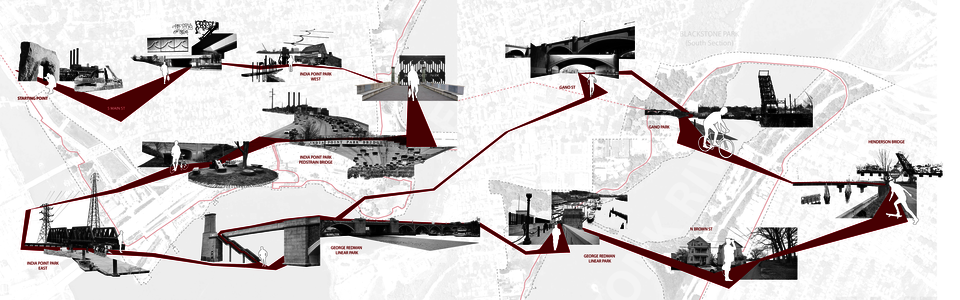

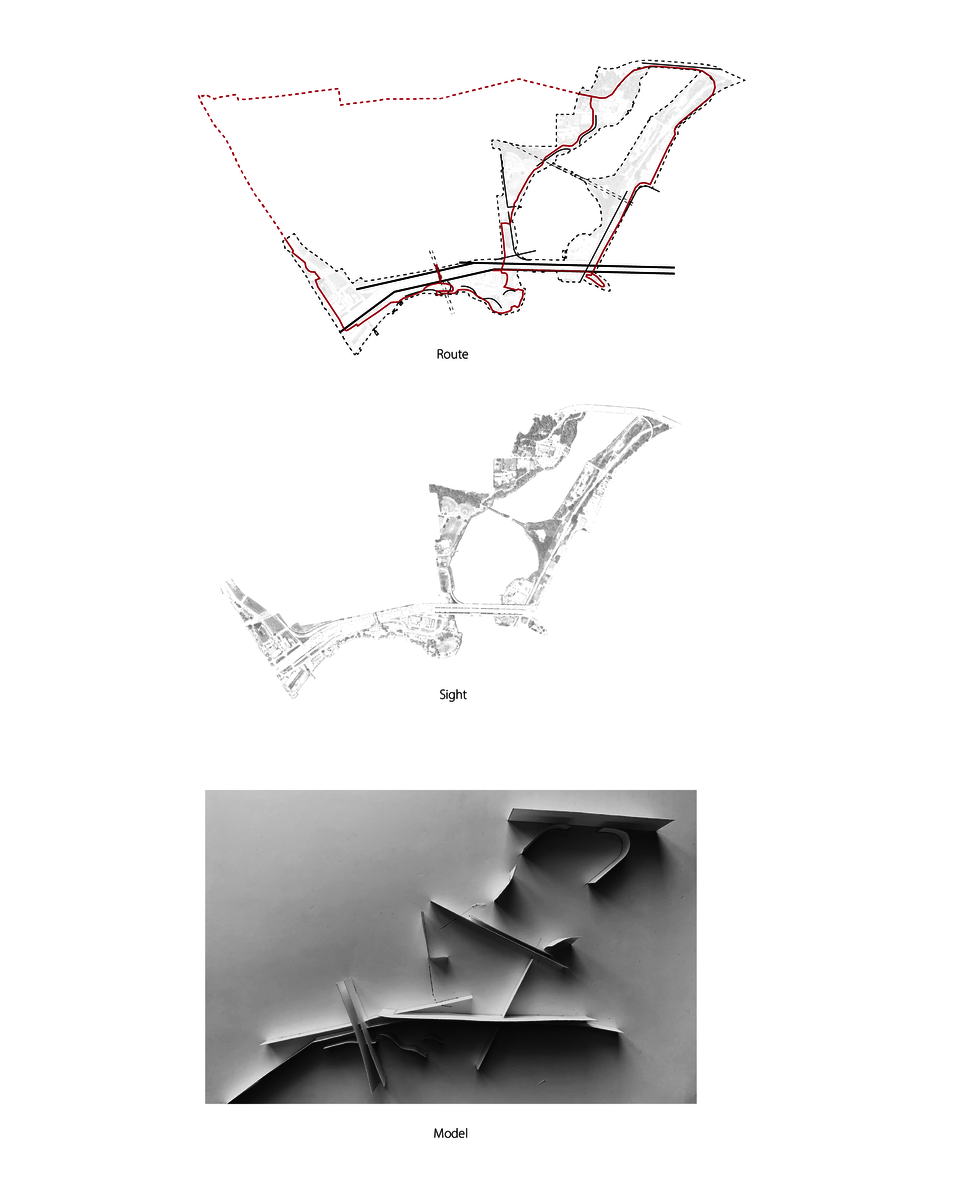

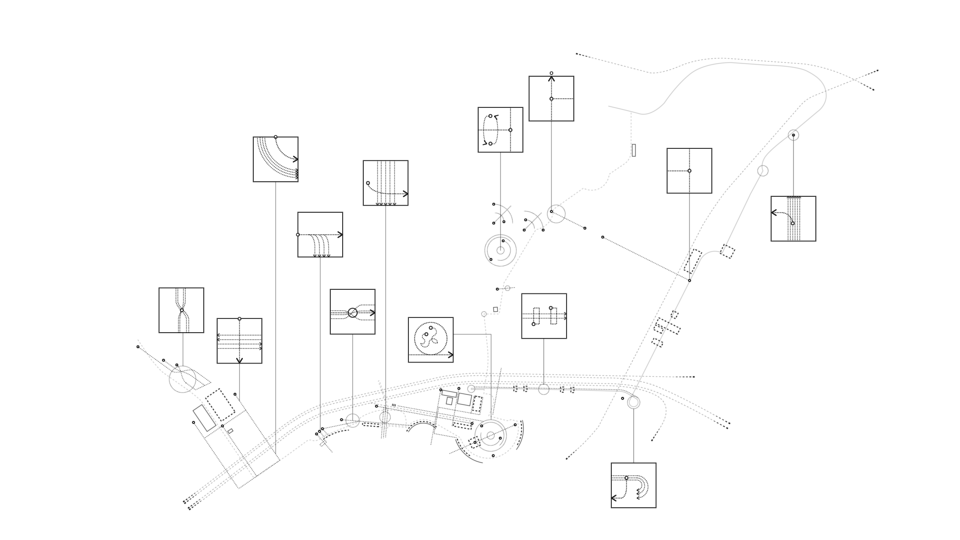

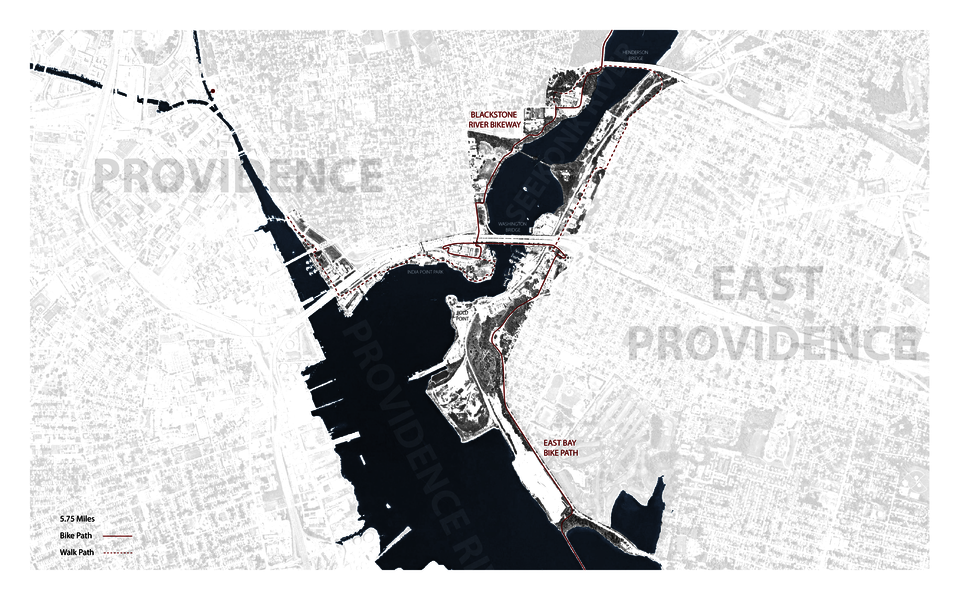

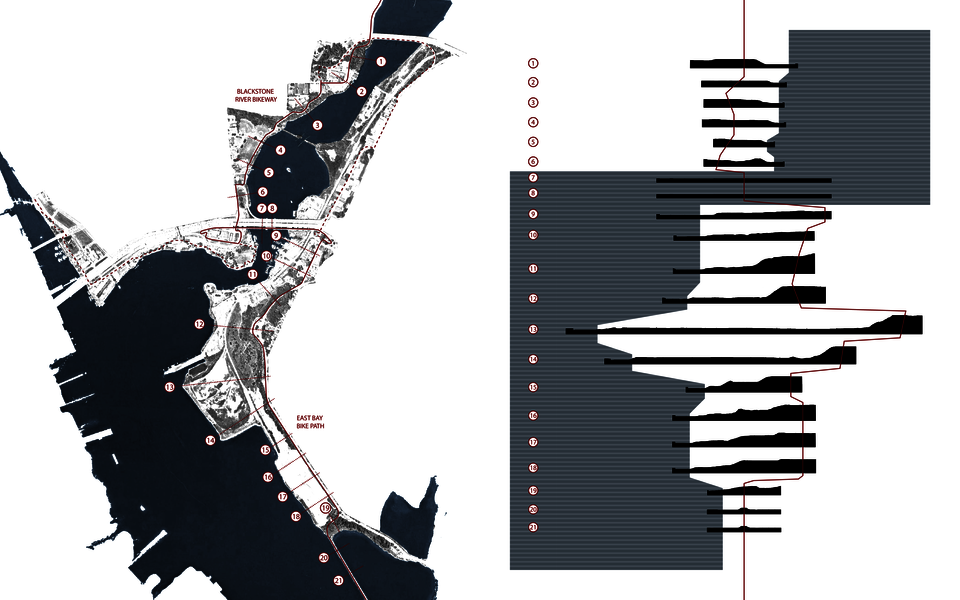

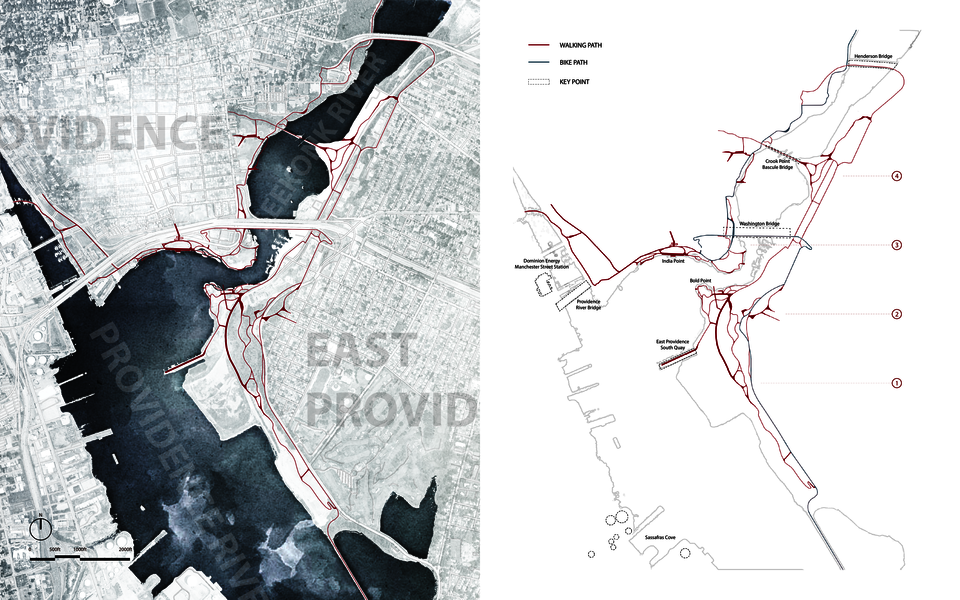

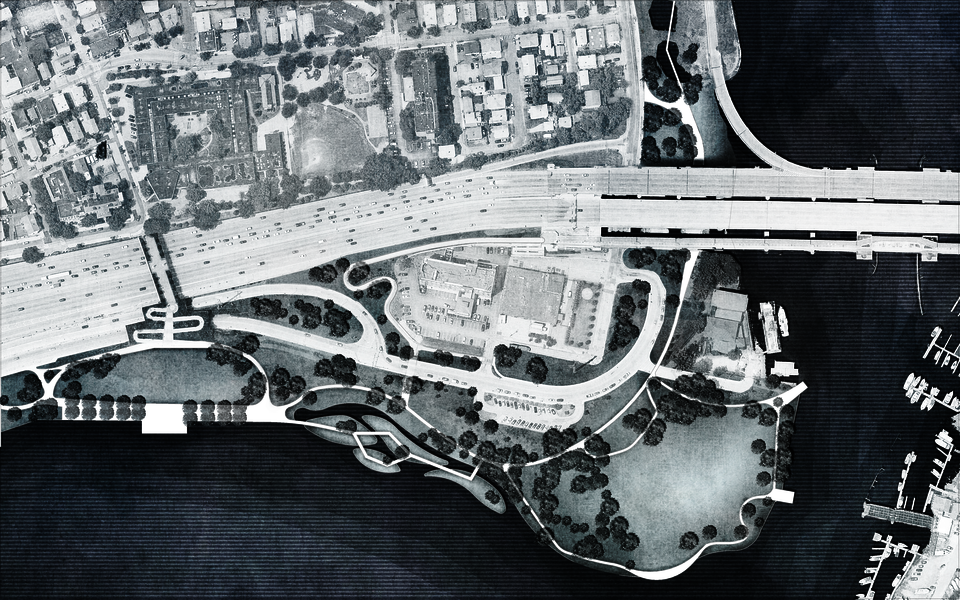

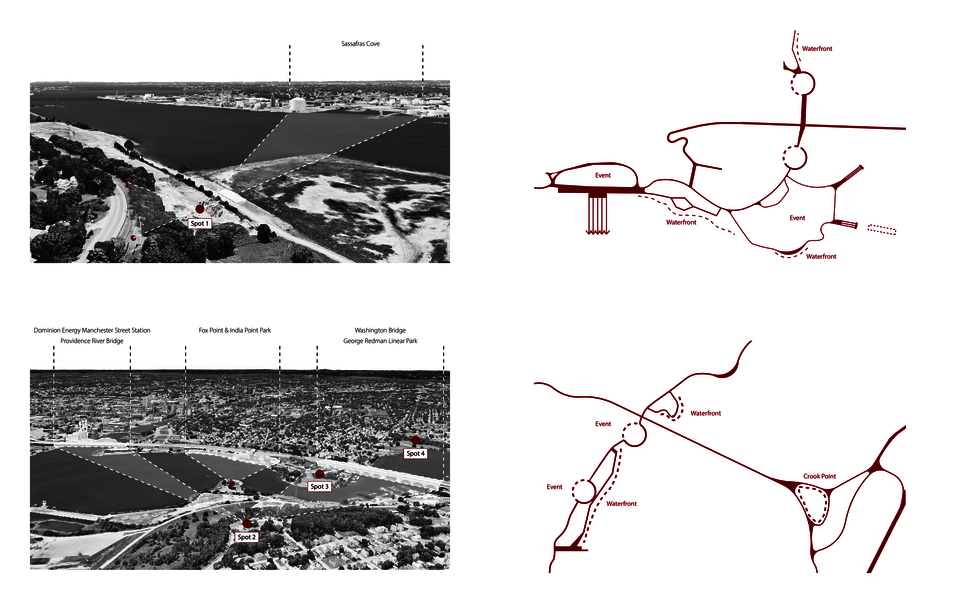

The project was divided into 3 phases and 6 chapters. It started with the study of precedent cases in the field of film and landscape. Through the deep analysis and transformation of certain films, a specific methodology was developed for the next step. In phase 2, to take a walk in the real world and record the observation and experience with a video camera. Used the methodology to analyze and translate this footage from 3 aspects, viewshed, event, and focus. The outcome of these analyses was used for developing two different spatial installations as prototypes to convey the experience and understanding of landscape. Through the re-interpretation of the relationship between the cinematic equipment in the installation, filmic narrative and cinematography could be developed as a design strategy in order to enhance the experience and improve the readability of landscape. Finally, a pedestrian system on two bike paths in Providence (East Bay Bike Path & Blackstone River Bikeway) was redesigned, which encouraged people to connect the fragments in the city during the walk on this path, and interact with the environmental conditions, and build their own observation and understanding on the landscape.

TRAVERSING THROUGH MOTION PICTURE TO LANDSCAPE

Since the advent of the film camera, it was possible to reconstruct landscape fragments in a continuous way. Rather than the earliest landscape paintings, the portability of a film camera made it a new eye for humans, it could be taken to any place, recorded the landscape from different angles. These images influenced academic research, narratives, and even wars.

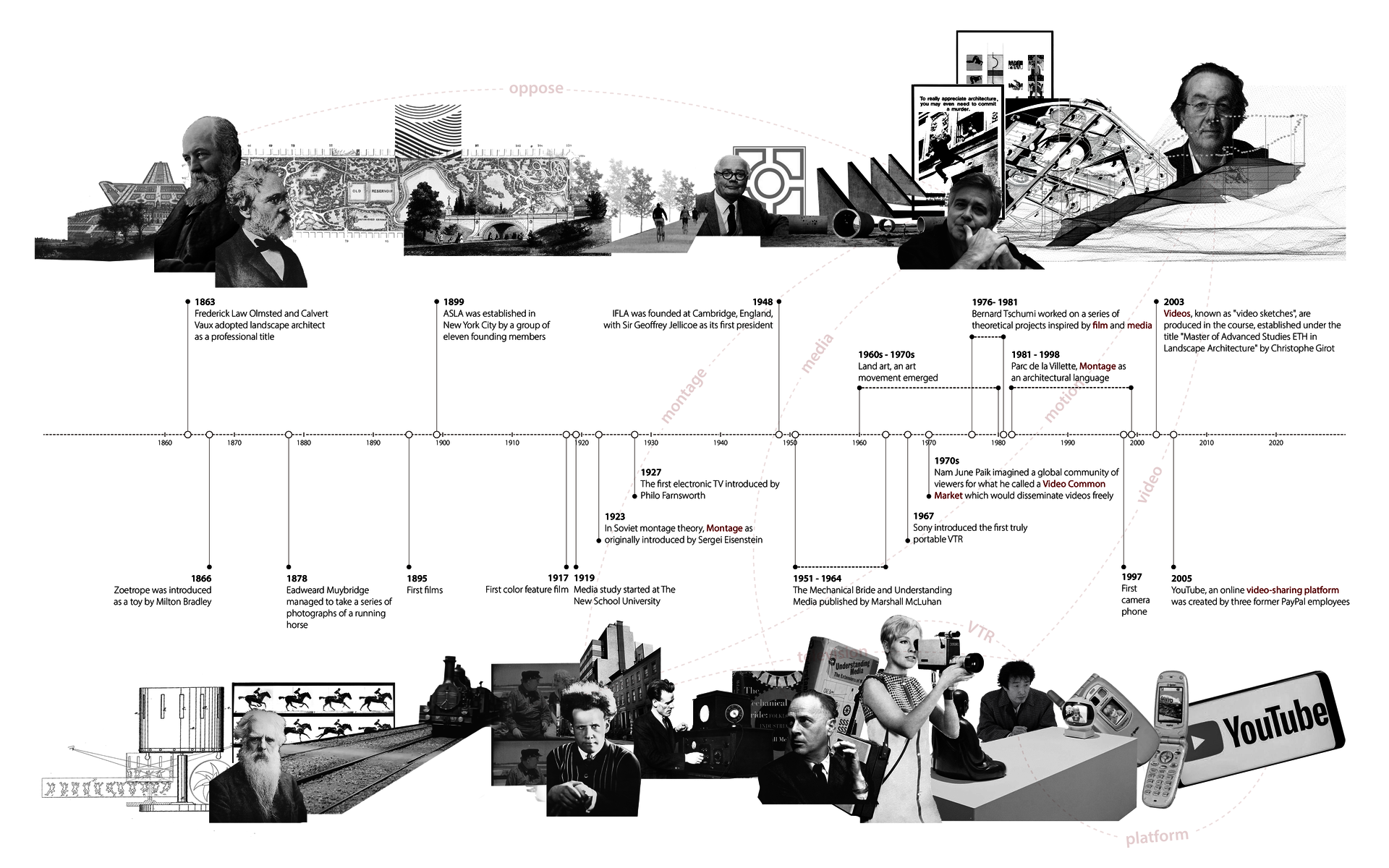

Excluding landscape gardening and landscape painting, landscape architecture as a profession and film developed at about the same time around the 1860s. And through these recent 100 years, the invention and theory in both fields kept affecting each other.

In the digital age, escaping from the influence of media is impossible. The mechanism, image, sound, all the techniques are permeating our living environment. It should be the responsibility of every designer to fight against this tendency that technology becomes the replacement of the human body and physical environment. Instead of grasping the “content” of any medium, to understand the indescribable texture, hear the imperceptible sound and explore the world from an unobservable perspective, the idea of cinematic experience could be deeply explored.

The motion picture, as one of the most important mediums in recent 100 years, had a great impact on our perception of reality. The technique, device, and language developed from cinema also changed the way we observe and understand the landscape, and rebuild the narrative of past, present, and future. In order to explore a new dimension and perspective of landscape, the film study would have great potential to make a contribution to human’s extended perception and representation of landscape and raise the possibility of defining a new typology of the performative landscape even beyond space and time.

Image

▲ The parallel timeline between film media and landscape architecture.

Image

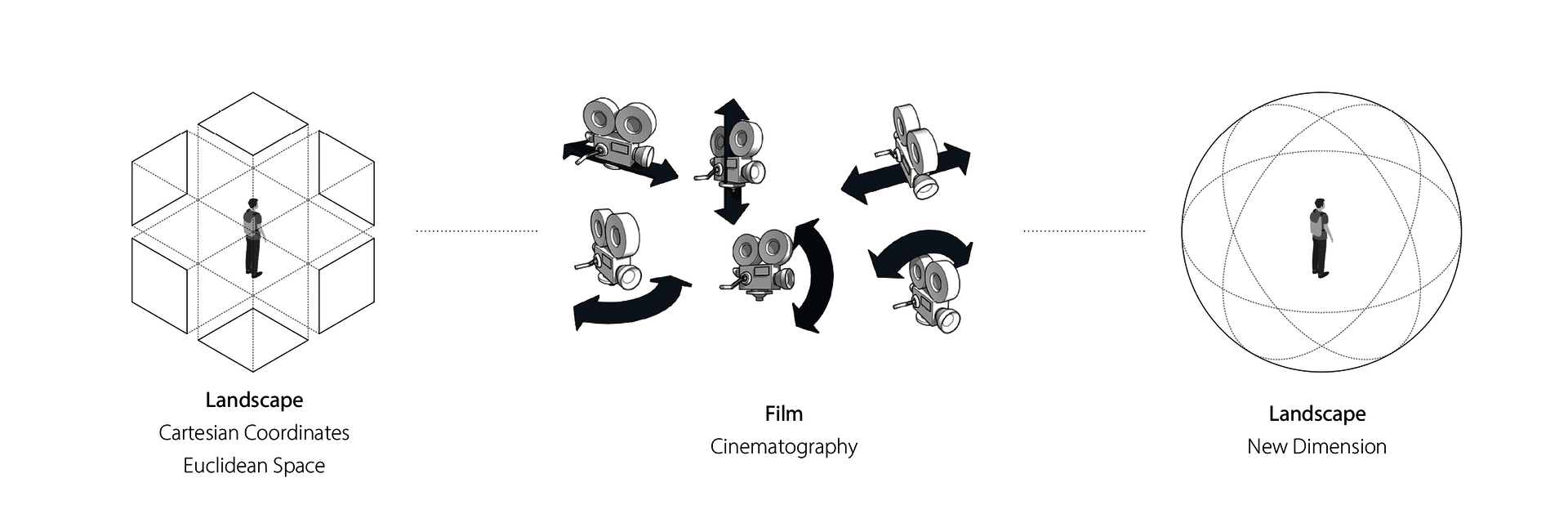

▲ Spatial dimension and cinematography

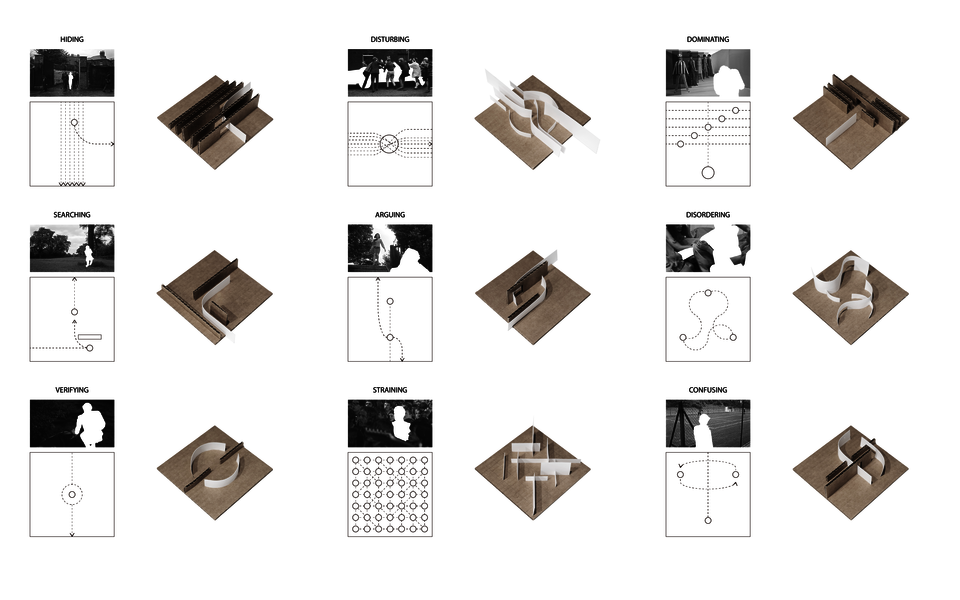

In general, the way we perceive the physical space is based on the rule by Cartesian coordinates and Euclidean space, that’s how we can understand the 3-dimensional world with 6 different directions (Up, Down, Left, Right, Front, Back). It’s not how the world was constituted, of course, but a clear orientation is crucial to humans when we get into reality. However, the filmic language and cinematography could easily break this rule and create a dreamlike and unreal world. That’s why lots of filmmakers overindulge in cinema all the time. The film became a perspective and power for them, in order to reconstitute the world they understand and rebuilt a new dimension in landscape as narrative to express their values and statement. To analyze three different films and reconstruct and translate the narrative space in each of them, in order to test the idea of a new dimension of landscape with several experimentations with multi-medium.

A WALK IN REAL WORLD

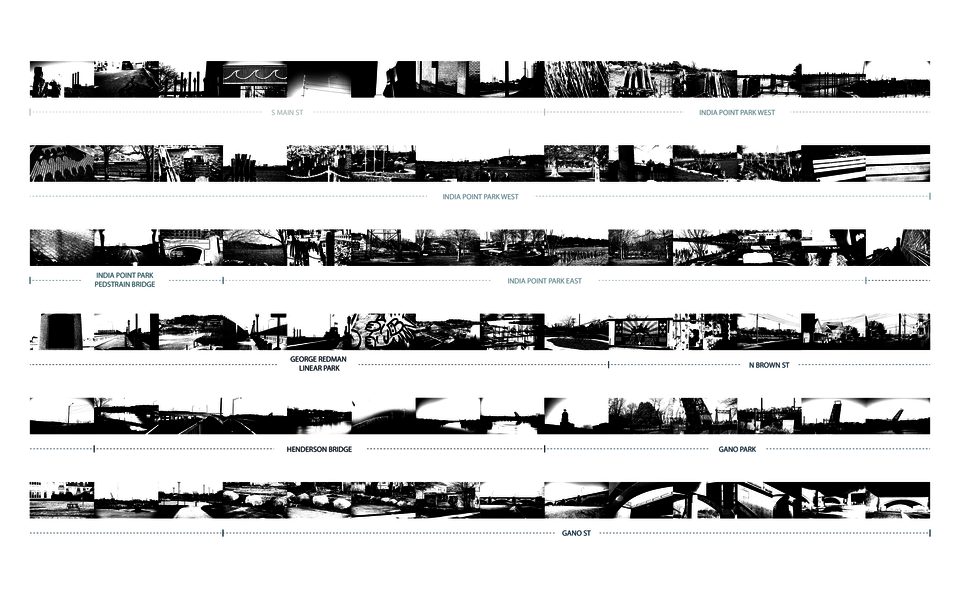

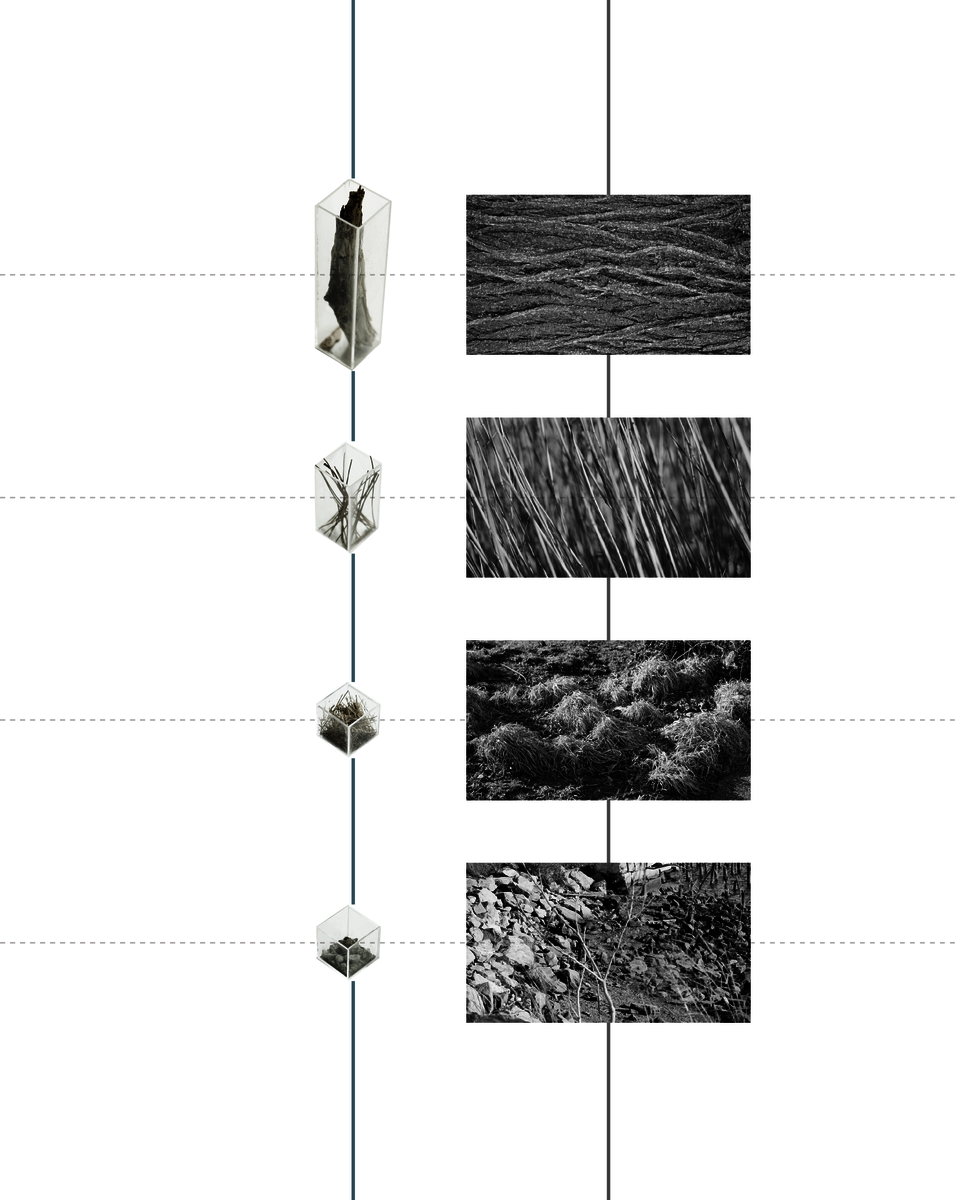

In Phase 2, all the research will be based on a walk in Providence and the observation on it. I will develop my methodology to explore more observations in the real world which are based on the research and experiment on film theory and media study in Phase 1. On the other hand, inspired by psychogeography. These observations will shy away from the spectacle of consumerism in our living environment and more focus on the perceptual, emotional and fluid aspects of landscape. Camera and cinematography will be a very important point of view to help me build the linear experience of filmic world.

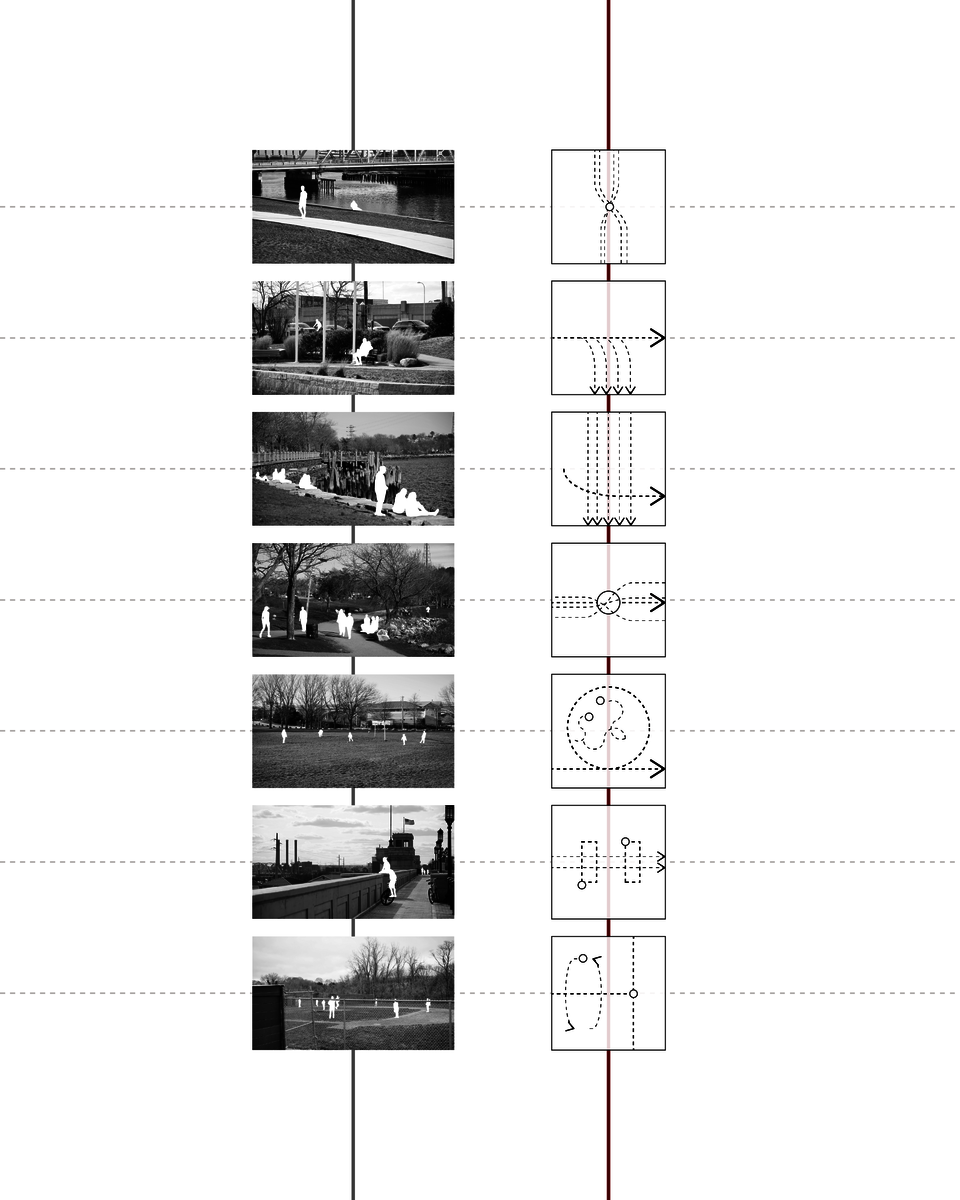

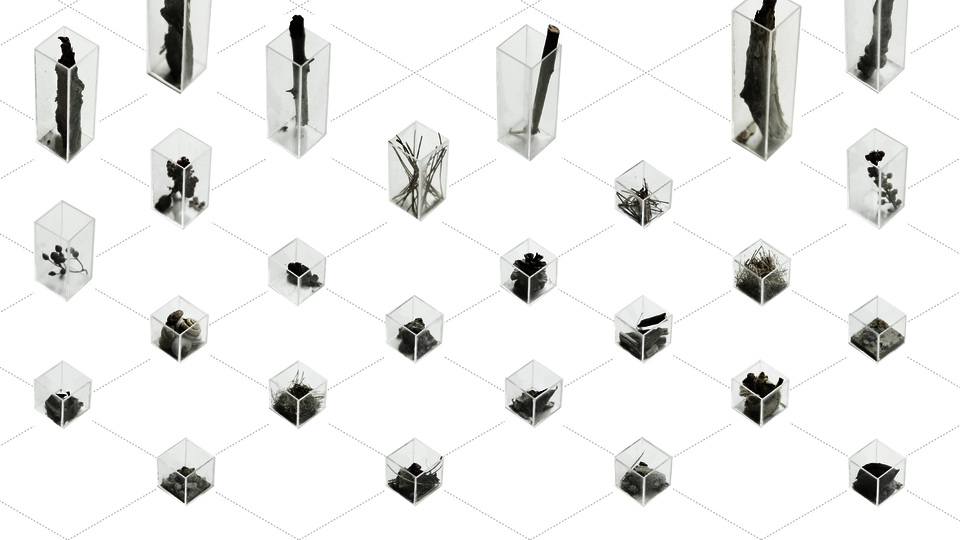

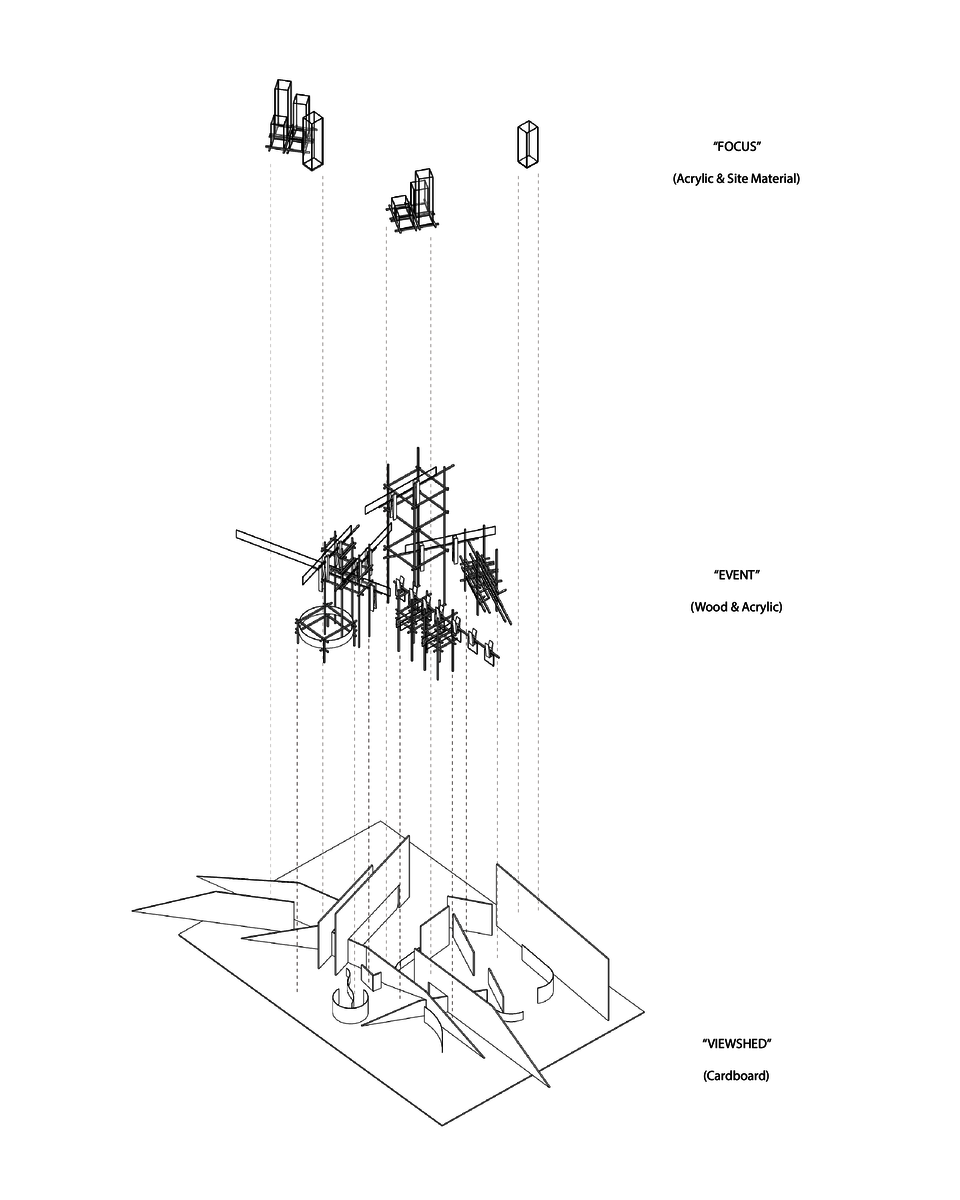

The first step is to use the moving image as a gaze to experience a site, I try to capture something unusual, unique, special but also represent the site and also my subjective experience, regardless of emotion, viewshed, events and so on. Then, to start to analyze and transform those moving image and build an installation which can be as a configuration and spatial form that reconstruct my linear experience on the site and use moving image to engage with it and activate it.

INSTALLATION AS CONFIGURATION

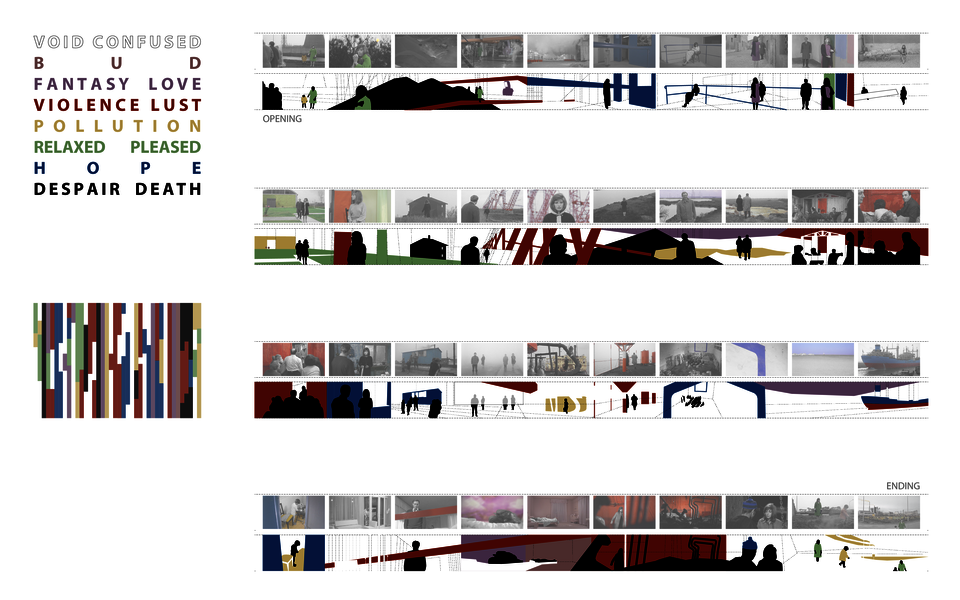

After all the walks and analysis, I started engaging with installation to combine all these found and experiences into space. This is a process to transform the perceptual, linear connection and sequence through this certain route in Providence and East Providence into the world of creative configuration or structure, which can represent the narrative and emotion in my film about the walk.

It is about the memory, the perception and the context of the walk. On the other hand, it is also a start to revisit and reinspect a familiar site from another perspective and explore a design language and spatial form that I can use to respond to the site.

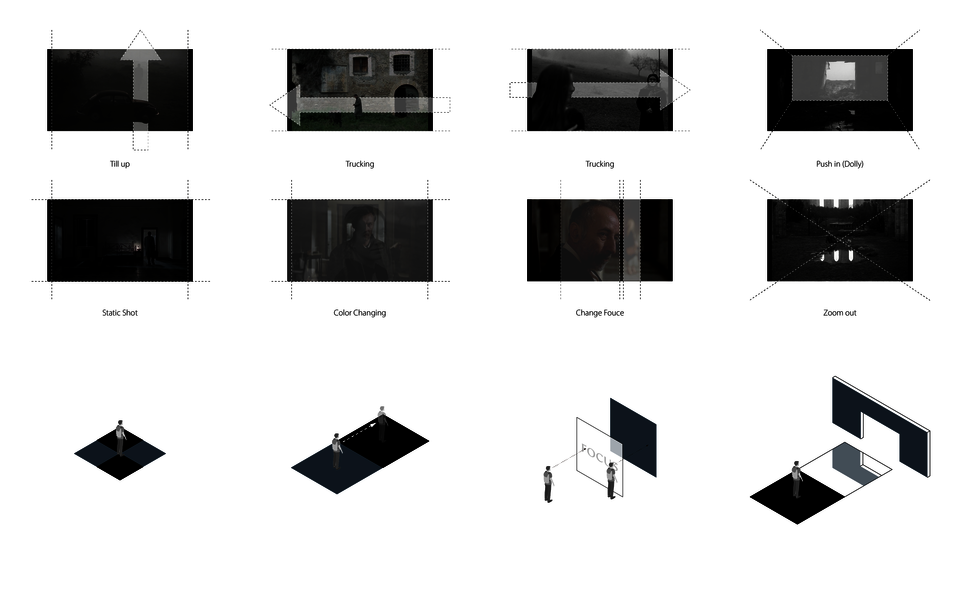

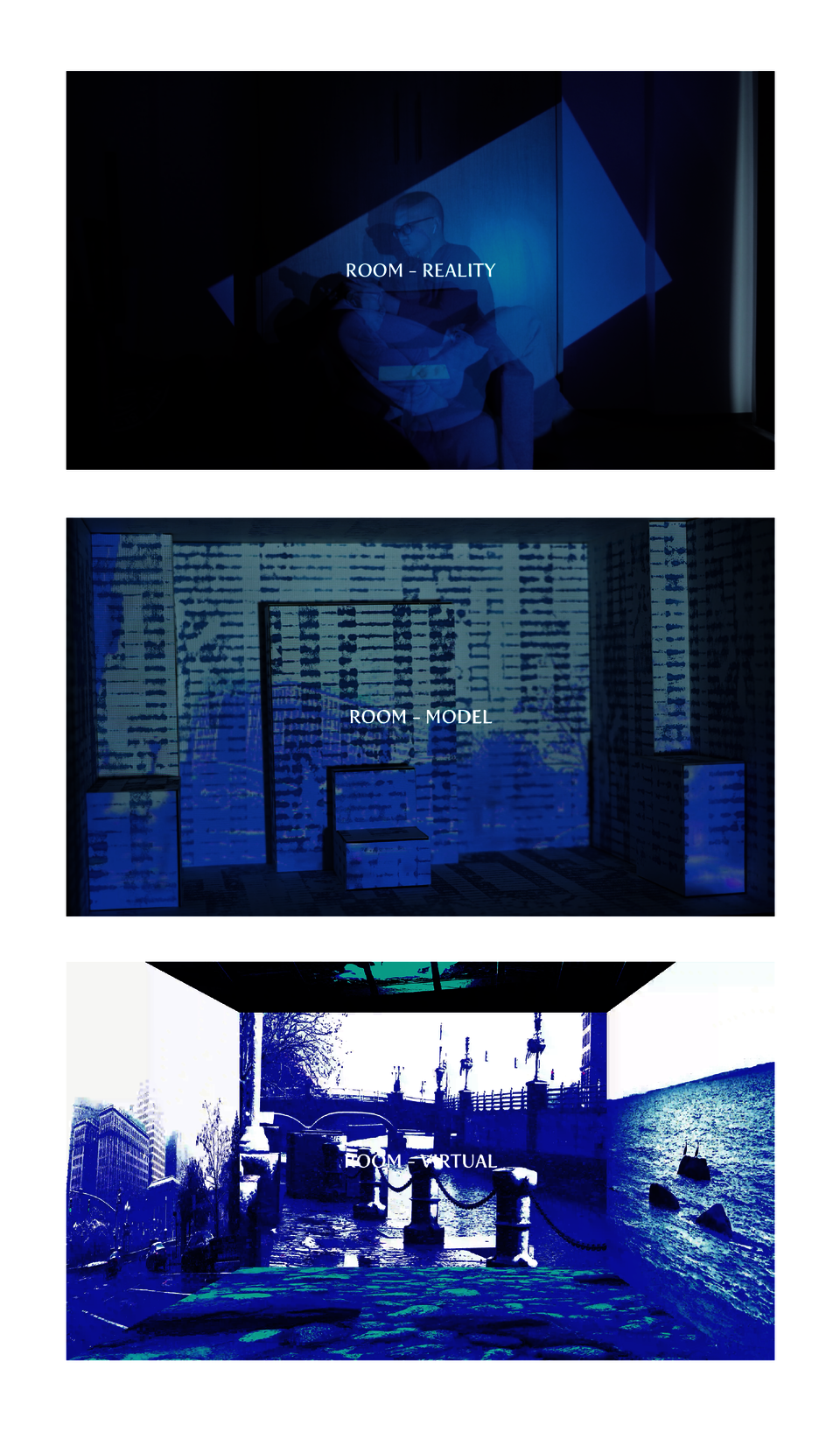

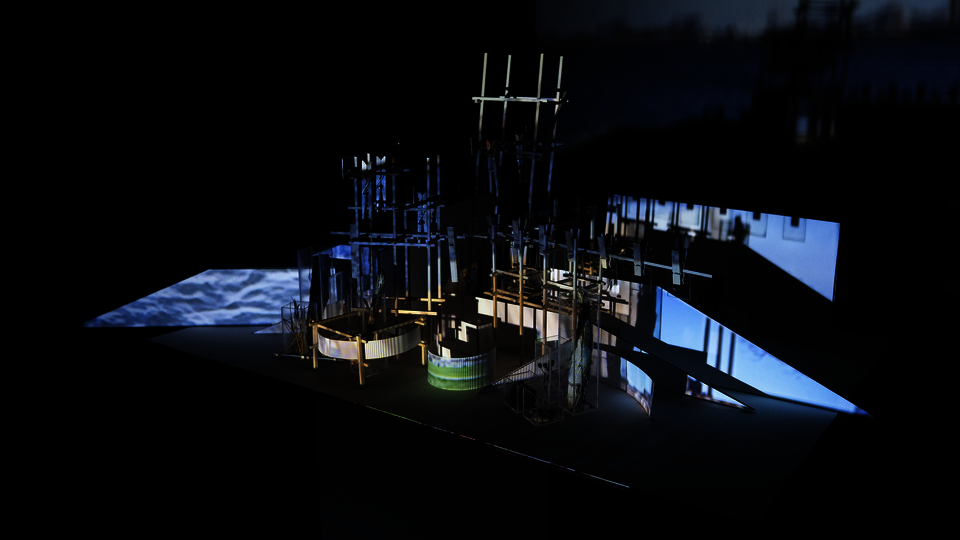

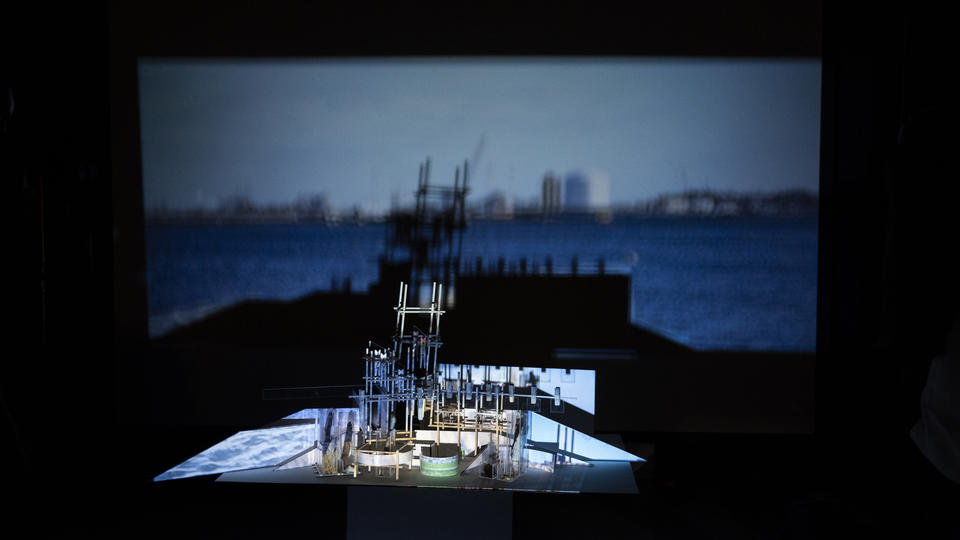

Image

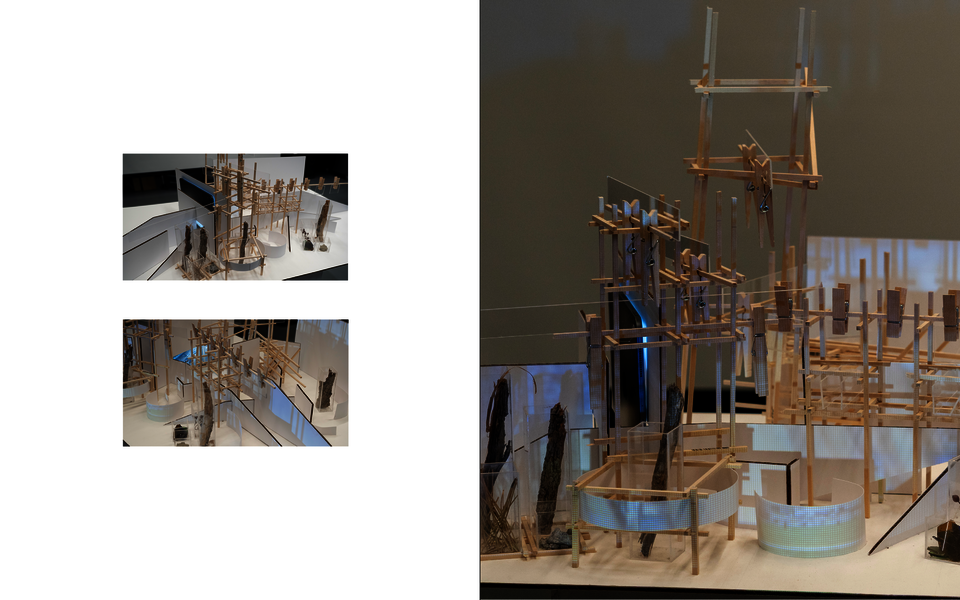

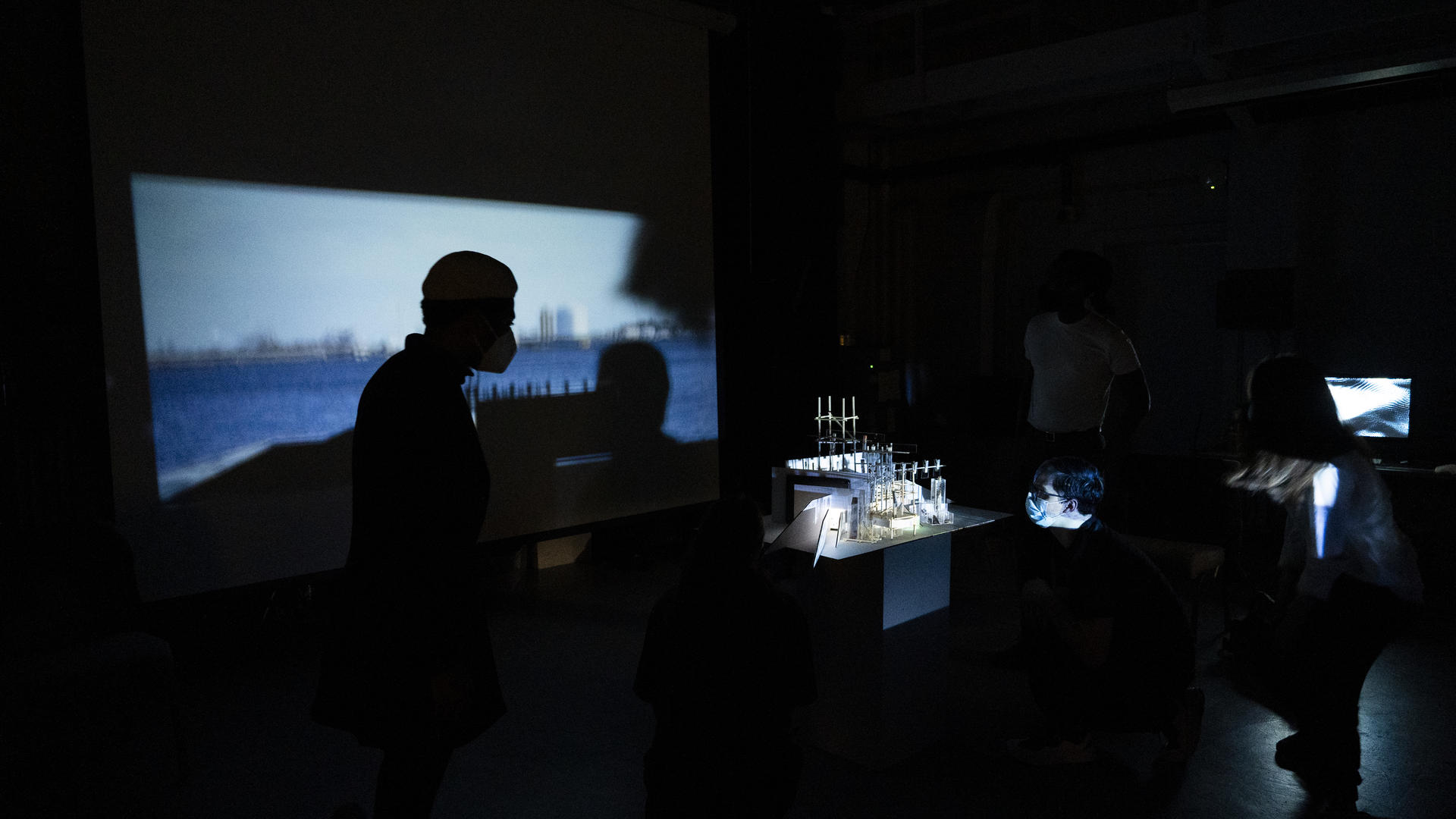

▲ Spatial installation in Blue studio, RISD Auditorium.

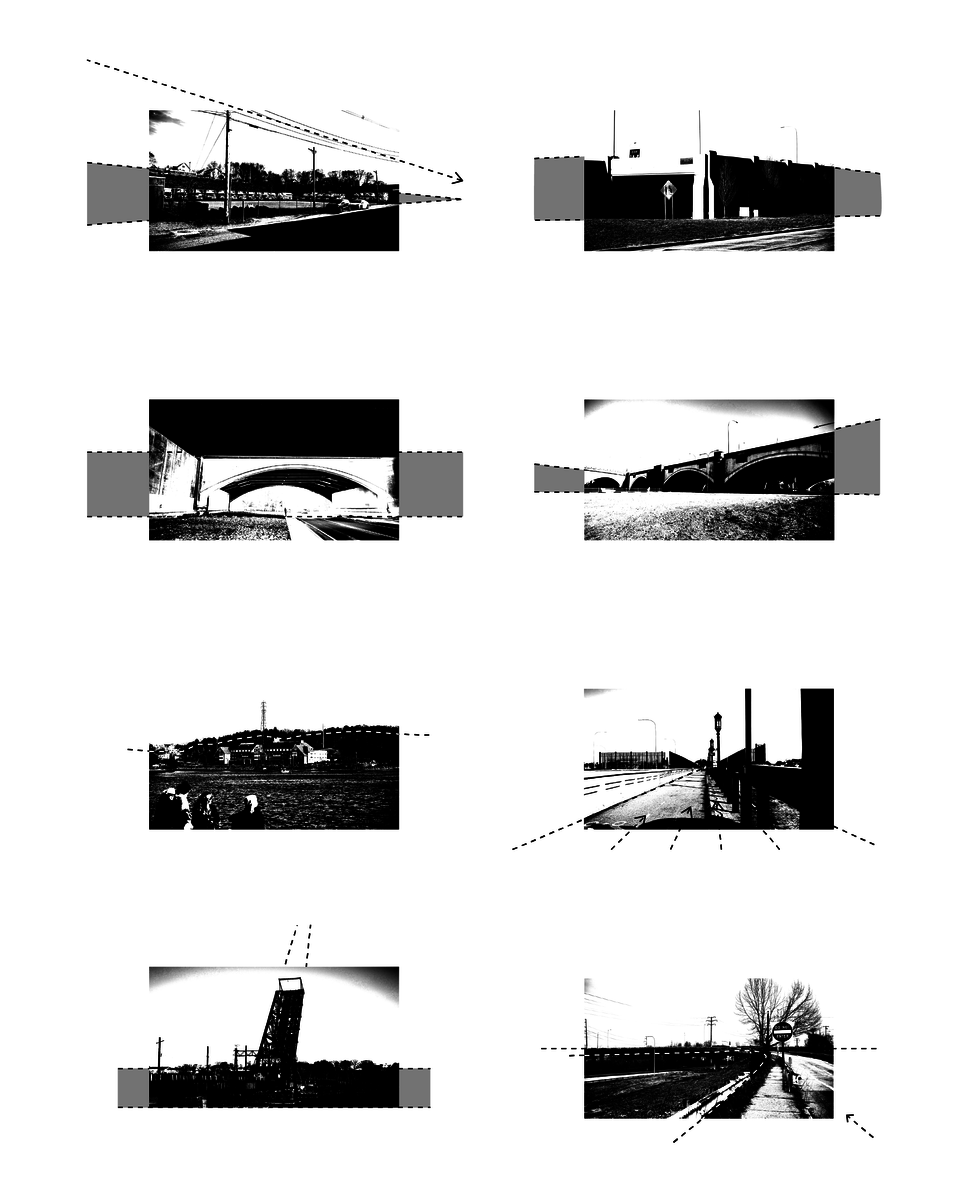

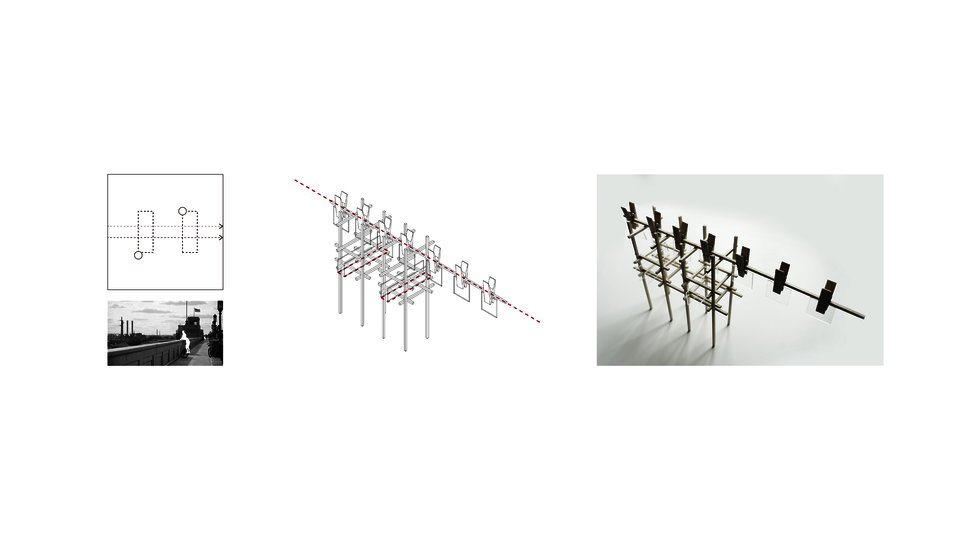

In cinematography, each camera movement has its own focus, which allows the audience to pay attention to what the filmmaker would like to show. Can we translate this means into experience in the real world?

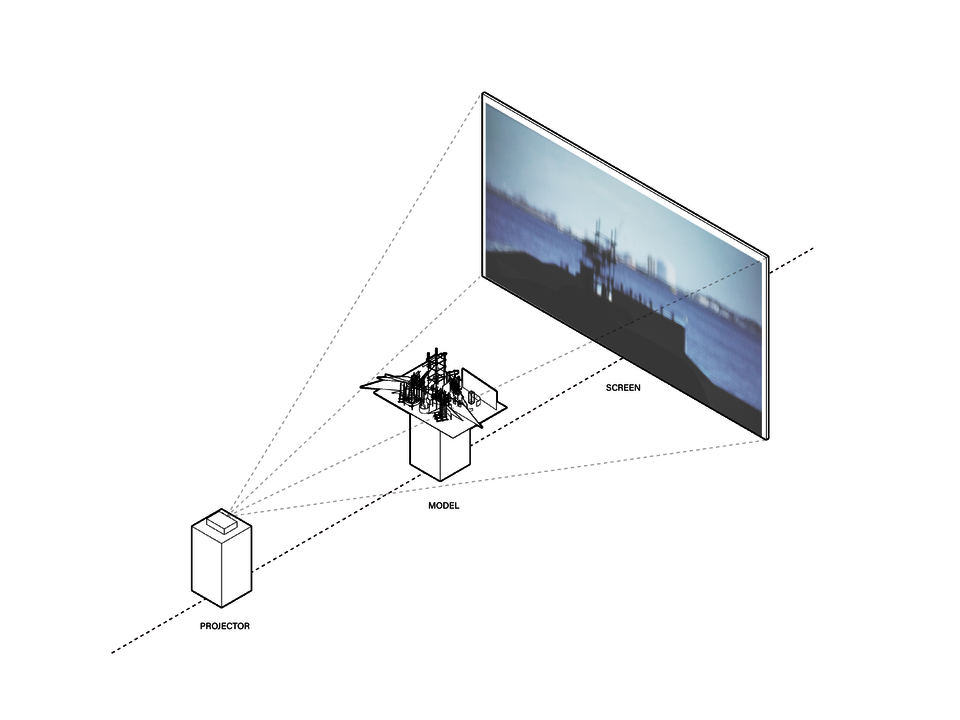

In order to understand this relationship, I re-interpreted the set of my installation into the experience in the physical environment. We can consider the relationship between the projector, the model and the screen as the relationship between ourselves and the landscape. If we use our eyes as the projector, the object and materials outside, regardless of the vegetation or the architectural feature, would become the model between the screen and projector. These objects would reframe our sight and experience on the landscape to generate our own understanding of the real world as our mind, as same as the image on the screen intervened by the model. In order to experiment with this idea of translating this relationship, I built another installation to test it.

Image

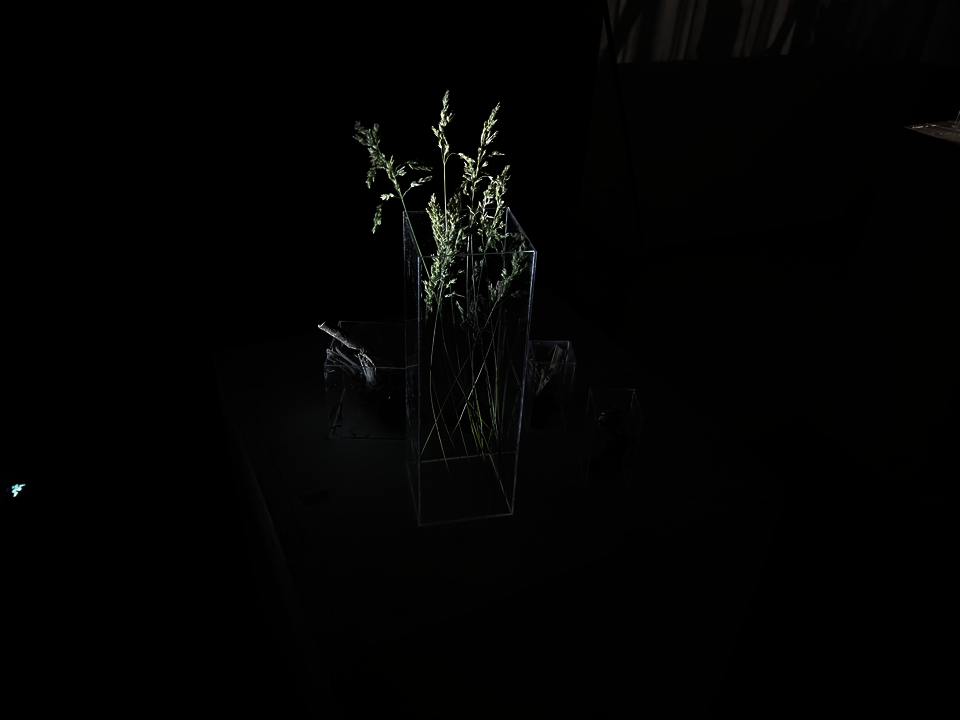

I set up two different prototypes to test the idea of reframing sight. I used the same structure developed from a certain event to reframe the moving images (a wide angel shot and a close-up shot) on the board in two different ways in order to test the visual experience at different distances.

This installation was installed in the blue studio in FAV Department. Through the four relationships of light and shadow listed below, I placed the moving image I recorded during the walk, the materials collected on the site, and the structure translated from events in Blue Studio, and combined with the spatial conditions of the studio to complete my installation. The audience could experience the influence of distance changing on the visual focus through the light, shadow and projection in it, various interactions could be approached in a narrow indoor space with simple circulation. Simultaneously, the walk of the audience would cast a shadow and reframe the sight of other audience. As a result, the movement of the audience became a part of the performance of the installation and affect other audience’s experiences.

A MARKERLESS PATH

During my walks, I found plenty of historical markers, which told the history of Providence in text and image, regardless of the events, landmarks, or important people. There are totally 161 historical markers in Providence County, and some of them are marked with maps and circulation to connect with other markers.

A large number of historical contexts are no longer present in the city. The Markers could document this information and make it known to the public. However, should these markers dominate a person’s walking? Do people have to be guided by these markers? Is it possible to draw people’s attention to the phenomena existing at present by defining a markerless but readable landscape?

▲ Historical markers in Providence County.

A filmmaker could only use video and sound to convey the narrative with very few subtitles and dialogue. As same as the walking experience, people can also discover hidden corners of the city and get different viewshed by a redesigned pedestrian system without the guidance of a marker or signboard, in order to understand what constitutes our landscape and the topography, and even explore the relationship between ecology and hydrology.

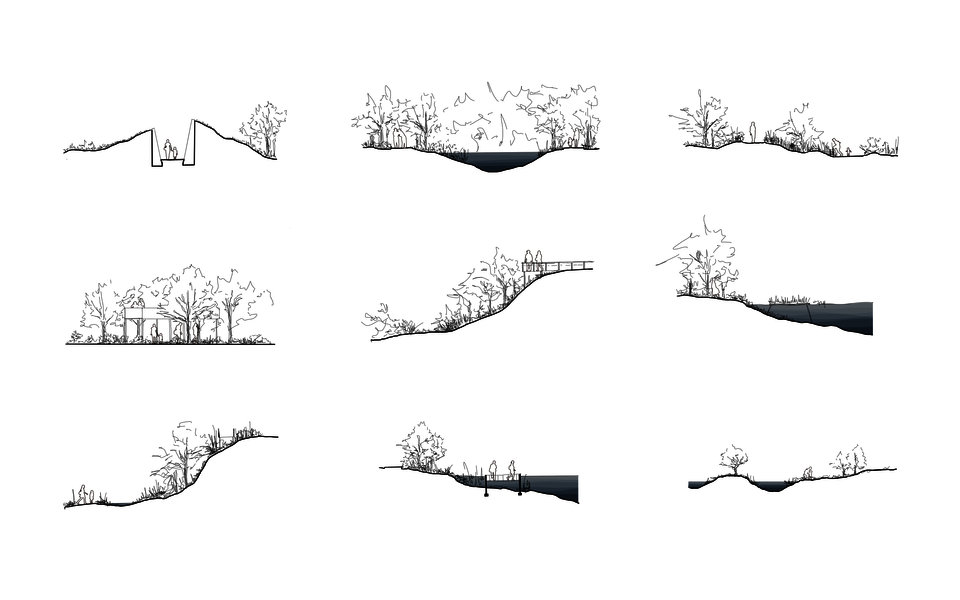

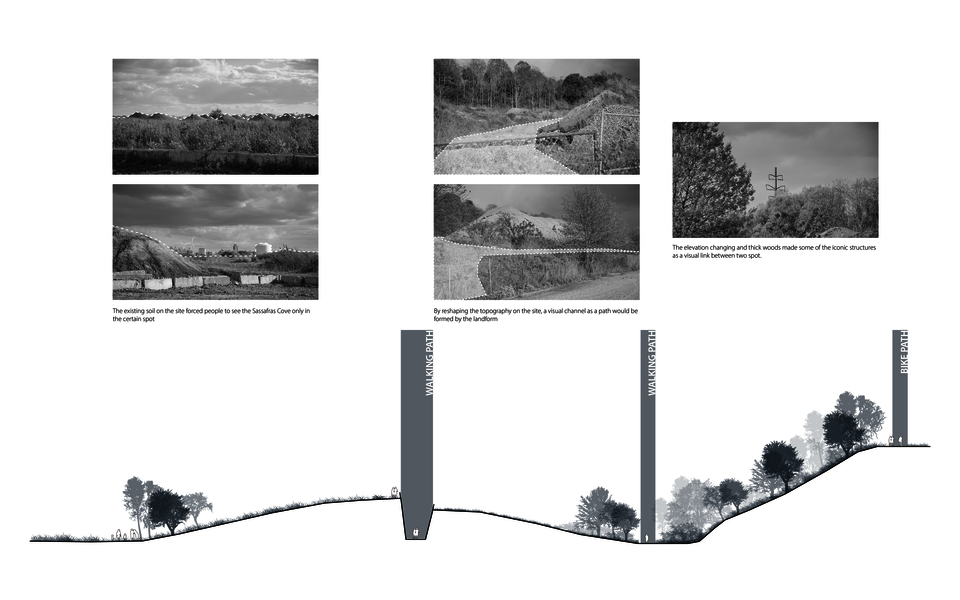

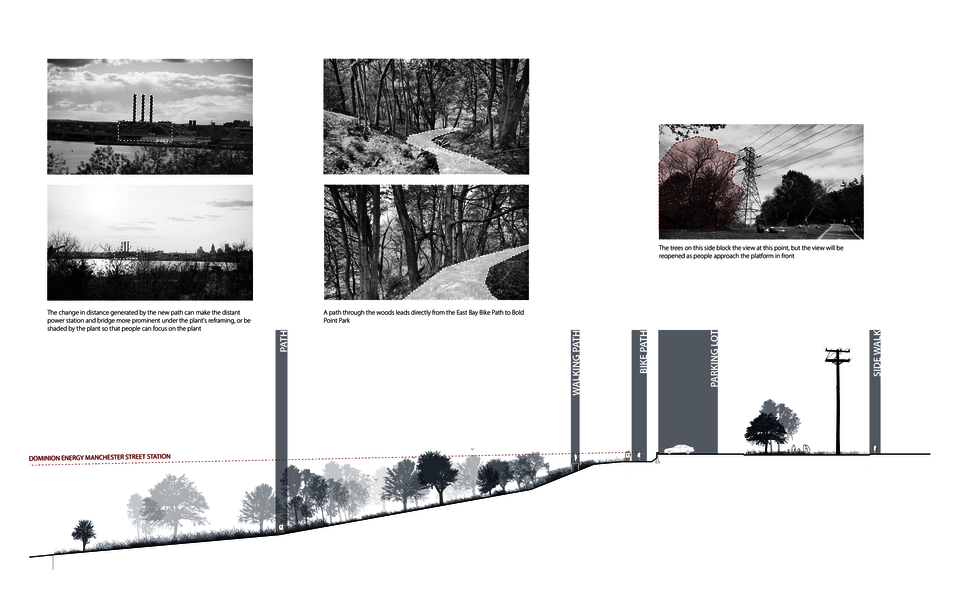

I began to redesign the pedestrian system on the route I walked, improving the accessibility in different locations and providing people the opportunity to interact with the water edge and the woods. The viewshed and elevation changing would be crucial to the design. They could provide a very rich visual experience for the pedestrian system, while the different environmental conditions will allow people to experience the transition between the different sections. Through the control and design of the distance, the walk, as camera movement, could draw together the city fragments by zooming in and out or tracking.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andy, Clark. 2004. Natural-Born Cyborgs: Minds, Technologies, and the Future of Human Intelligence. Oxford University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by J. A. Underwood. Penguin Great Ideas. Harlow, England: Penguin Books.

Christophe Girot, Sabine Wolf, Fred Truniger, Landscape MediaLab ETHZ. 2010. LandscapeVideo: Landscape in movement. gta Verlag.

Eisenstein, Sergei M., Yve-Alain Bois, and Michael Glenny. “Montage and Architecture.” Assemblage, no. 10 (1989): 111-31. Accessed May 6, 2021. doi:10.2307/3171145.

Edward, A., Shanken. 2015. Systems. London : Whitechapel Gallery.

Graeme Harper, Jonathan Rayner, and Ebooks Corporation. 2010. Cinema and Landscape : Film, Nation and Cultural Geography. Bristol : Intellect Books.

Gidal, Peter. 1976. Structural Film Anthology. London : British Film Institute.

Giannetti, Louis D., and Jim Leach. 2008. Understanding movies. Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Helphand, Kenneth I. “Landscape Films.” Landscape Journal 5, no. 1 (1986): 1-8. Accessed May 7, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43322989.

J. B. Jackson. 1984. Discovering the vernacular landscape. New Haven : Yale University Press.

Jena, Osman. 2019. Motion Studies. Ugly Duckling Presse.

Jim, Davis. 1953. “The only dynamic art” Films in Review 4, no. 10 (1953): 511–515.

John, Cantine, Susan Howard, and Brady Lewis. 2011. Shot by shot : a practical guide to filmmaking. Pittsburgh, PA : Pittsburgh Filmmakers.

Jussi, Parikka. 2015. A geology of media. Minneapolis ; London : University of Minnesota Press.

Kongjian Yu, and Valerio Morabito. 2020. Landscape Architecture Frontiers 041: Observation and Representation. Oro Editions.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding media: the extensions of man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Murch, Walter. 2001. In The Blink of an Eye: a Perspective on Film Editing. Los Angeles, California: Silman-James Press.

Swaffield, Simon R. 2002. Theory in landscape architecture: a reader. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Tarkovsky, Andrey. 1988. Sculpting in Time. Translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Truniger, Fred. 2013. Filmic mapping: film and the visual culture of landscape architecture. Berlin: Jovis Verlag.

Tschumi, Bernard. 1981. The Manhattan transcripts. London: Academy Editions.

Virilio, Paul. 1989. War and cinema: the logistics of perception. London: Verso.

William, Gibson. 2012. Distrust that particular flavor. New York : G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

FILMOGRAPHY

Feature Film:

Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

The Steamroller and the Violin (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1961)

Ivan’s Childhood (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1962)

Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972)

The Mirror (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975)

Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

Nostalghia (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1983)

The Sacrifice (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986)

Mysterious Object At Noon (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2000)

Blissfully Yours (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2002)

Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004)

Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2006)

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2010)

Cemetery of Splendour (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2015)

Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1982)

Powaqqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1988)

Naqoyqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 2002)

The Adventure (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960)

The Night (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1961)

Eclipse (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1962)

Red Desert (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1964)

Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

The Colossus of Rhodes (Sergio Leone, 1961)

A Fistful of Dollars (Sergio Leone, 1964)

For a Few Dollars More (Sergio Leone, 1965)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966)

Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968)

Once Upon a Time... the Revolution (Sergio Leone, 1971)

Once Upon a Time in America (Sergio Leone, 1984)

The Society of the Spectacle (Guy Debord, 1974)

Sans soleil (Chris Marker, 1983)

Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor & Verena Paravel, 2012)

Short Film:

21-87 (Arthur Lipsett, 1964)

A Letter to Uncle Boonmee (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2009)

A Movie (Bruce Conner, 1958)

A Walk Through H: The Reincarnation of an Ornithologist (Peter Greenaway, 1979)

All Water Has a Perfect Memory (Natalia Almada, 2001)

Ashes (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2012)

Castro Street (Bruce Baillie, 1966)

Critique de la separation (Guy Debord, 1961)

Dresden Dynamo (Lis Rhodes, 1971)

Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB (George Lucas, 1967)

Energies (Jim Davis, 1957)

Free Radicals (Len Lye, 1958)

Ilha das Flores (Jorge Furtado, 1989)

La jetée (Chris Marker, 1962)

Mothlight (Stan Brakhage, 1963)

NoNoseKnows (Mika Rottenberg, 2015)

Powers of Ten (Charles Eames and Ray Eames, 1977)

Semiotics of the Kitchen (Martha Rosler, 1975)

Squeeze (Mika Rottenberg, 2010)

T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (Paul Sharits, 1968)

The Garden of Earthly Delights (Stan Brakhage, 1981)

The City (Ralph Steiner and Willard Van Dyke, 1939)

This is a Television Receiver (David Hall, 1976)

Windows (Peter Greenaway, 1975)

Installation:

Air Writing, Fire Writing (Mary Lucier, 1975)

Calligrams (Steina and Woody Vasulka, 1970)

Flashlight Filmstrip Projections (Jennifer West, 2014)

Graft and Ash for a Three Monitor Workstation (Sondra Perry, 2016)

Imagination Dead Imagine (Judith Barry, 1991)

Influence Machine (Tony Oursler, 2000)

measuring stick (Sarah Sze, 2015)

Reflektorische Farblichtspiele (Kurt Schwerdtfeger, 1922/1967)

“Self Burial” Television Interference Project (Keith Arnatt, 1969)

Steam Screens (Stan VanDerBeek and Joan Brigham, 1976/2015)

Typhoon Coming on (Sondra Perry, 2018)

Vertical Roll (Joan Jonas, 1972)

Vertigo Sea (John Akomfrah, 2015)