ABSTRACT

Recently, Russian Government has been steering to-wards reviving what they claim to be “traditional Russian values”, which include heteronormativity, homophobia, gender binary, religious conservatism, etc.

Adding to this the suffocation of indepen-dent media and scholarship, these actions have resulted in a decades worth of works by Russian queer artists to be abandoned, buried in the archives, museum storages, never exhibited, or hidden under the tag of heterosexuality.

In this work I looked at the Russian queer cultural production from the Medieval Slavs until the current regime of Vladimir Putin. I argue that our recovery from that forced memory loss is vital for continuing an adequate discussion of Russian art history which should be informed with feminist and queer discourses.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Methods And Sources

Vocabulary and Translation

Literature Review

Chapter 1. Medieval Slavs

Chapter 2. Part 1. Silver Age

Part 2. The Revolutions

Chapter 3. The Birthplace of Russian Homophobia. The 1930s.

Chapter 4. Through The Brief Period Of Freedom Towards

The New Conservative (1991- Present)

Conclusion

Further Research

Bibliography

ARTEM EMELIANOV

Photo for Calvert Journal

2019

https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/11285/queer-moscow-o-zine-…

Image

Image

For the last 10 years, the Russian Government have been coming up with more and more repressive laws. Quite recently, a Russian queer feminist activist and theatre director, Yulia Tsvetkova was repeatedly charged repeatedly with, what is know commonly know as, Gay Propaganda Law. According to the government the law was introduced for the purpose of protecting children from being exposed to any positive representation of LGBTQIA, because it contradicts “traditional family values”. Even though the law is misdemeanor, she was charged with a felony and it is a separate long story why.

Similarly to Tsvetkova, many of Russian artists, public figures, scholars and activists have been and continue to be charged with that law for being outspoken about gender/sexuality. Everybody know the example of Pussy Riot. I have kept wondering what these “traditional values”, that are held so dear to the Russian government, are… Homosexuality was hardly ever prosecuted in the Russian It seems that the notorious values stop being so homophobic when it comes turning the spotlight to the actual but hidden histories.

My thesis is an attempt to do just that - to turn the spot light, to find what was swept under the rug, hidden and forgotten, to “redraw the boundaries of what counts as art and what counts as history” and to begin a dialog about gender and sexuality in the field of the Art History in Russia. My thesis will provide a detailed insight into the history of Russian LGBTQIA+ Art from the Medieval Russia to the Post-Soviet period, explore the history of its relationship with the governmental forces now and then and analyze art production at different times.

For my research I looked at artworks, photos, artist’s diaries, memoirs, illustrations, manuscript, graphic design, court cases, newspaper, journals, magazines, medical documents, etc. In addition to the written research, I have curated a profound catalog of visual sources with commentaries and research notes.

Image

Illustration of YULIA TSVETKOVA for Glamour Russia, @glamour_russia, https://www.instagram.com/p/CHvczVLM-iY/

Image

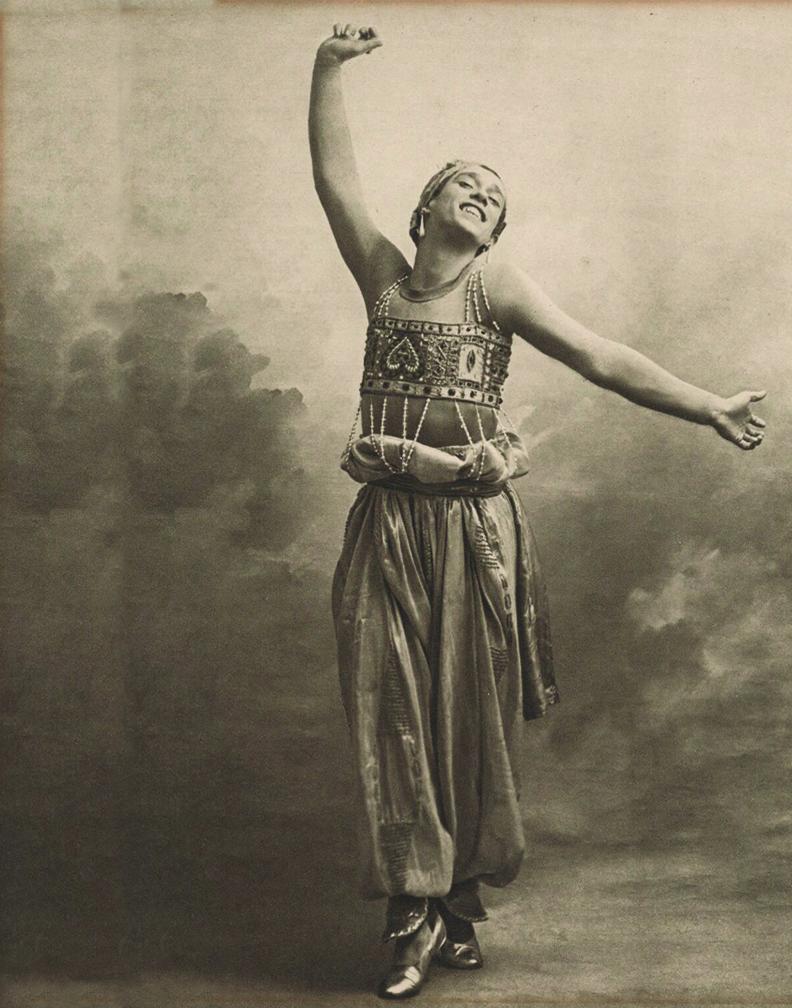

AUGUSTE BERT, Vaslav Nijinsky in ‘Shéhérazade’, Photogravure, 1911, 19 x 13 cm, National Portrait Gallary

My research gas been driven by the notion of “memorylessness” . I have a deep interest in collective memory, and how things end up in it, in what belongs and what does not, realizing how distorted our past is and how many false memories are in it, selected and planted by those in power.Talking about Russia… In some ways, the conversations about social justice and equality are about memory. Accepting painful memories and cruelties of our past, trying to heal, learning from our mistakes, and filling in the gaps are all necessary steps for making happier memories for those who are to outlive us. Our memories affect how we see our present and form our future. This research is an attempt to dig up these memories, and bridge at least some of the gaps.

“Writing and remembering Russia’s queer past investigates the problems of “memoryless” LGBT movement in a cultural and political environment that resists the recognition of its history. My argument here is that without adequate historical research and creative and thoughtful memory work, the future of Russian LGBTQ citizens will be weakened.”

Dan Healey, Book 1. Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 23.

“And yet, as the expanding field got gay and lesbian history attests, the queer frontier exists not only in the future but also in the past . At the best contemporary construction, queerness enables us to see the past differently, to recover otherwise lost representation, and to renew the collective and creative force of alternative sexually.”

Joseph Allen. Boone, Queer Frontiers: Millennial Geographies, Genders, and Generations (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2000), 349.

Throughout the work I use the term queer (Queer art, queer visual culture, queer studies) as the word that incorporates variety of non-heterosexual and gender non-binary identities. However, there is no direct translation of the word queer into Russian. In the Russian context the word kvir/queer (borrowed from English) is still used by a small group of so called “cultural elites” or the younger queer community in bigger cities. However, there is not a Russian word that would be able to serve as the umbrella term. In addition to that uniting by one term people of many different communities, is problematic, I understand that. I understand that the cultural imperialism of the anglophone West is problematic. I will use the term queer but ask the reader to be aware of Anglo-American presumption of the word queer.

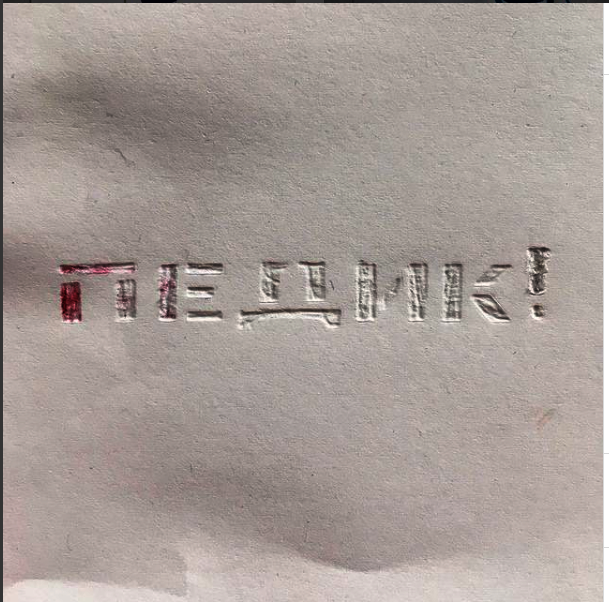

PASHA, Pedik/Faggot, 2020, Artists’s Instagram, @go_pasha_go

Image

Image

Sexuality and gender in Russia have been an understudied topic, not to mention queer studies and queer art history. It does not exist at all. Turn-of-the-century and the early revolutionary years mostly Pre-Stalin time, Russia was marked by an awakening of interest to issues of gender and sexuality which resulted in abundant cultural production and interest of the researchers. very interesting relationship with early revolutionary and the sexuality and gender studies. However it was destroyed in 1930s by the Stalin’s government along with many other freedoms. And since then homophobia has become an instrument for implementing their political agenda.

Unfortunately, such a long period of censorship (90 years with occasional breaks) resulted in a major knowledge gap, and there are currently not many queer studies coming from Russia. Young scholars are asked to mask their research under broader topics. ( In 2009 a researcher of political science Alexei Gorshkov defended his dissertation An Institutionalization of Minorities in the Sphere of Public Policy which was meant to be Sexual Minorities as a Political Issue in Modern Russia. Gorshkov had a vision for Russia’s only LGBT studies program at Perm State University, however he was never allowed to do it.)

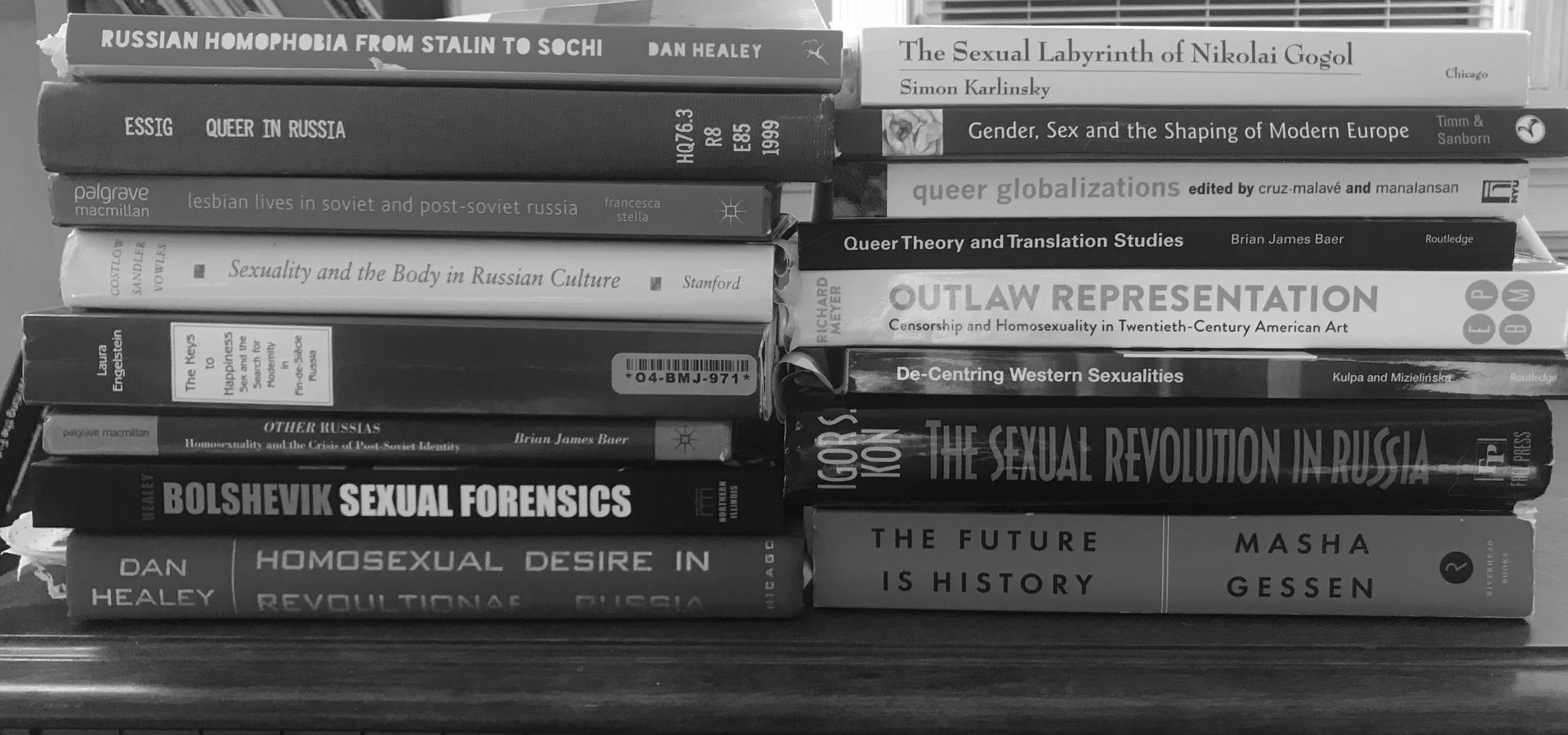

Since there is no previous research on Russia queer art, the documents I looked are mostly legal, medical and church texts, literature, literal criticism and scholarship. ‘Western’ scholars, on the other hand, have written on the topic of sexuality and gender in Russia quite extensively, which has enabled studies about sexuality in Russia not to die out completely.

Since Russian gender and sexuality studies are still trying to win their place even, the away around the system seems to be independent media, journalistic, activists and educational project have more chances for publications and for public outreach in Russia.

Since I started this research I found out about two upcoming related projects by a Russian artists out of New York, Yevgeniy Fiks and a researcher Maria Engstörm. Fiks recently announced at a conference at the University of Pennsylvania that a book, he has edited about Russian Queer Art, will be released in 2021/22. Maria Engstörm, an Associate Professor of Slavic Languages at the Department of Modern Languages, Uppsala University is currently working on a research project called Visuality without Visibility: Queer Visual Culture in Post-Soviet Russia, but it has not been published yet. Engstörm’s texts will also be included in Russian Queer Art book edited by Fiks.)

MEDEIVAL SLAVS

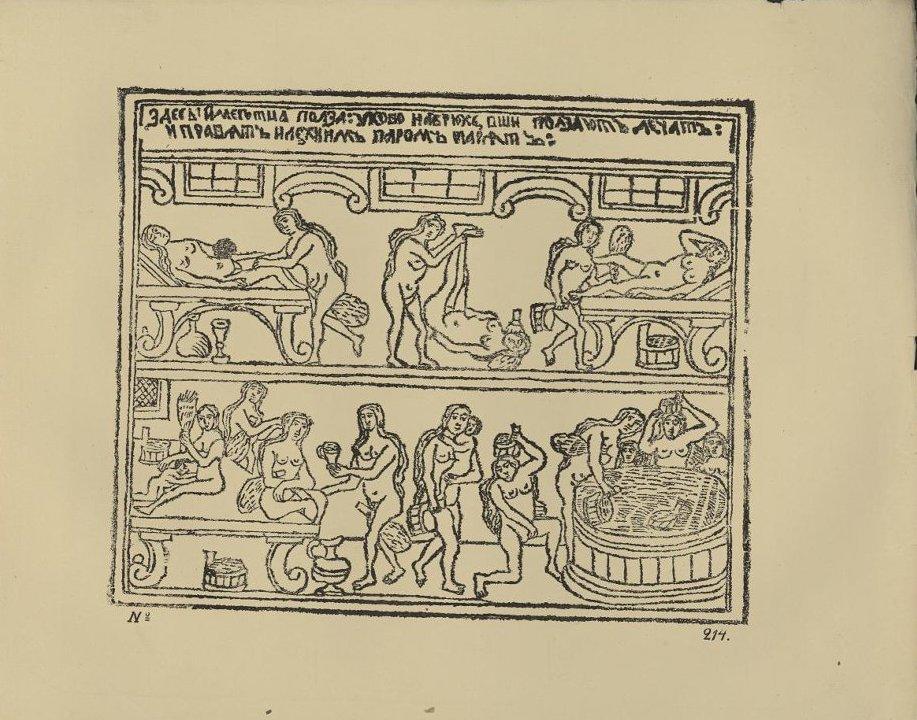

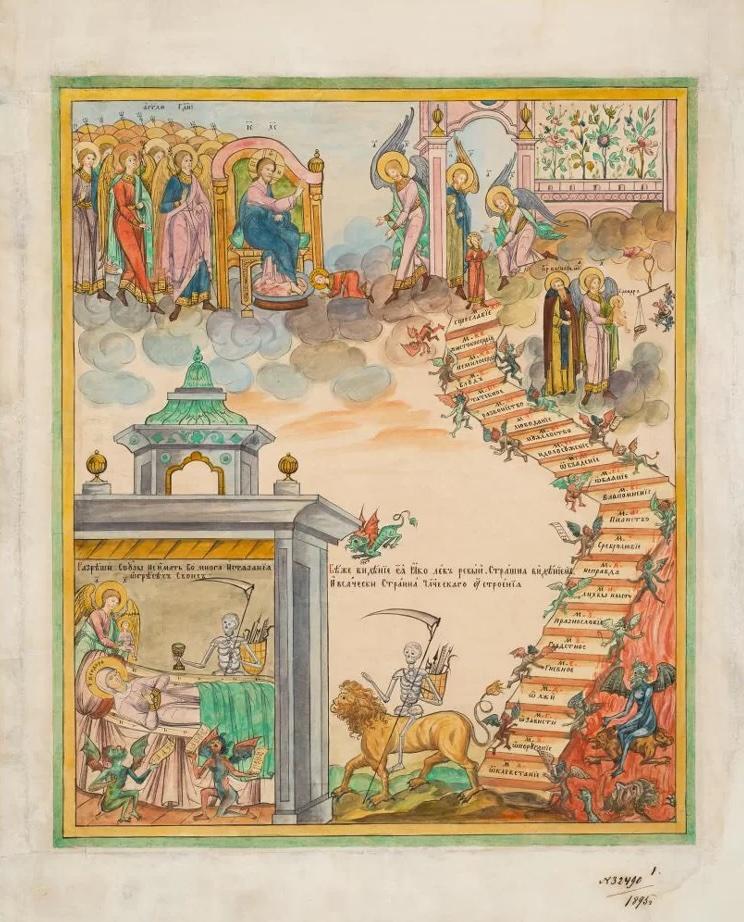

Early Orthodox Slavs considered sexuality a public matter and same sex desire was not consider a legal crime. It was a subject to religious jurisdiction, which considered all sexuality a problem without dividing into heater and not. During that I was looked at different lubki (Russian folk woodblock ) which give peeks into everyday life. This one has bania (bathhouse in it) And then I realized that also church frescos can be a good source. Legally homosexuality was never banned till 1835 de jure and till 1930s de facto. In later 1700s and 1800s Russia had a huge fashion for gender transgression, huge what we would call now drag scene. And here is another translation problem, I use the term drag meaning what we would call травести , which is a performance in Russian, but when we say travesti in English it is completely different, it is gender identity.

UNKOWN LUBOK ARTIST, Russian banya, second half of XVIII century, lithography on laid paper, 30,7х45 cm, Collection of the State Historical Museum, Moscow

UNKOWN LUBOK ARTIST, Tollboths of St Pheodora, Second half of the XIX century, 65,5 х 52,4 cm, Collection, State Historical Museum, Moscow

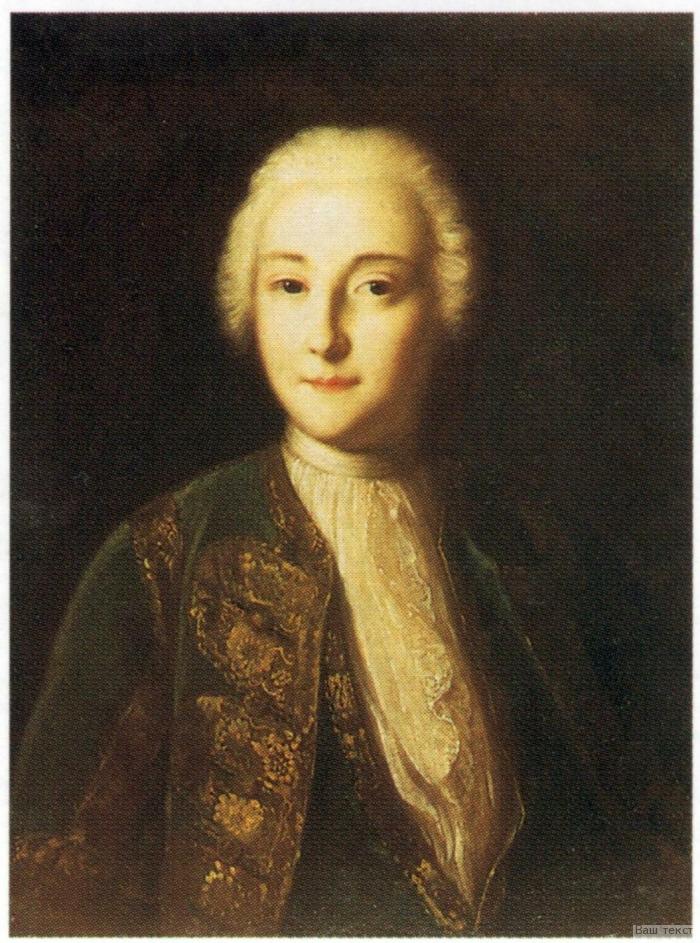

LOUIS CARAVAQUE (supposedly), Elizaveta Petrovna in Male Attire, 1740s, canvas, oil paint, 64 х 48,5 cm, Collection of the Tretyakov Gallery

TURN OF THE CENTURY

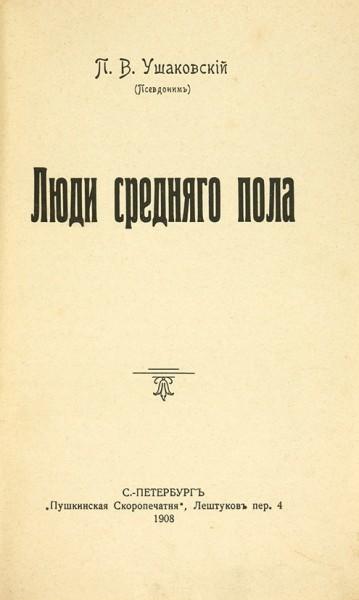

By the 19 century the rampant urban homosexual subculture was formed. Interest towards he topics of sexuality and gender transgression at the turn of the century was on its peak and resulted in vibrant cultural production as well as breakthroughs in Russian and early Soviet scholarships. In fin de siecle Russia there was no separation between queer and non-queer art scenes or sort of conforming /non conforming , the production by queer artists of the time was creme de la creme of the Russian art scene and brought fame to the Russian Silver Age cultural revolution. The politics of the early Soviet government around gender and sexuality was very interning, very exciting. I am talking about the period between the two revolutions and before Stalin.

Image

Participants of a Wedding and a Masquerade in St Petersburg, Photo taken by a sailor Afanasii Shaura, 1921, Central State Archive of St. Petersburg

UNKOWN ARTIST, A cover for the book by P.V. Ushakovskii ‘People Of Intermediate Sex‘, 1908, Public Domain

Image

Image

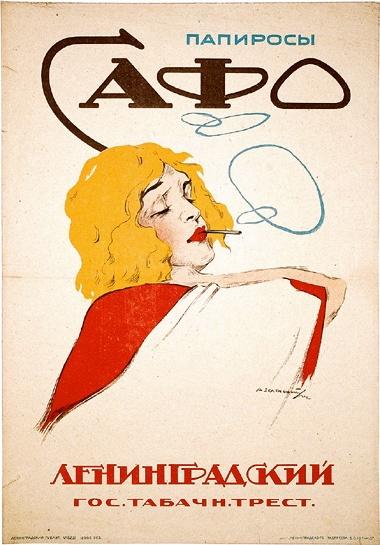

ALEXANDER ZELENSKY, 1920, Poster for Safo cigarets, 59,5 х 41 cm, Public Domain

THE BIRTHPLACE OF HOMOPHOBIA

Image

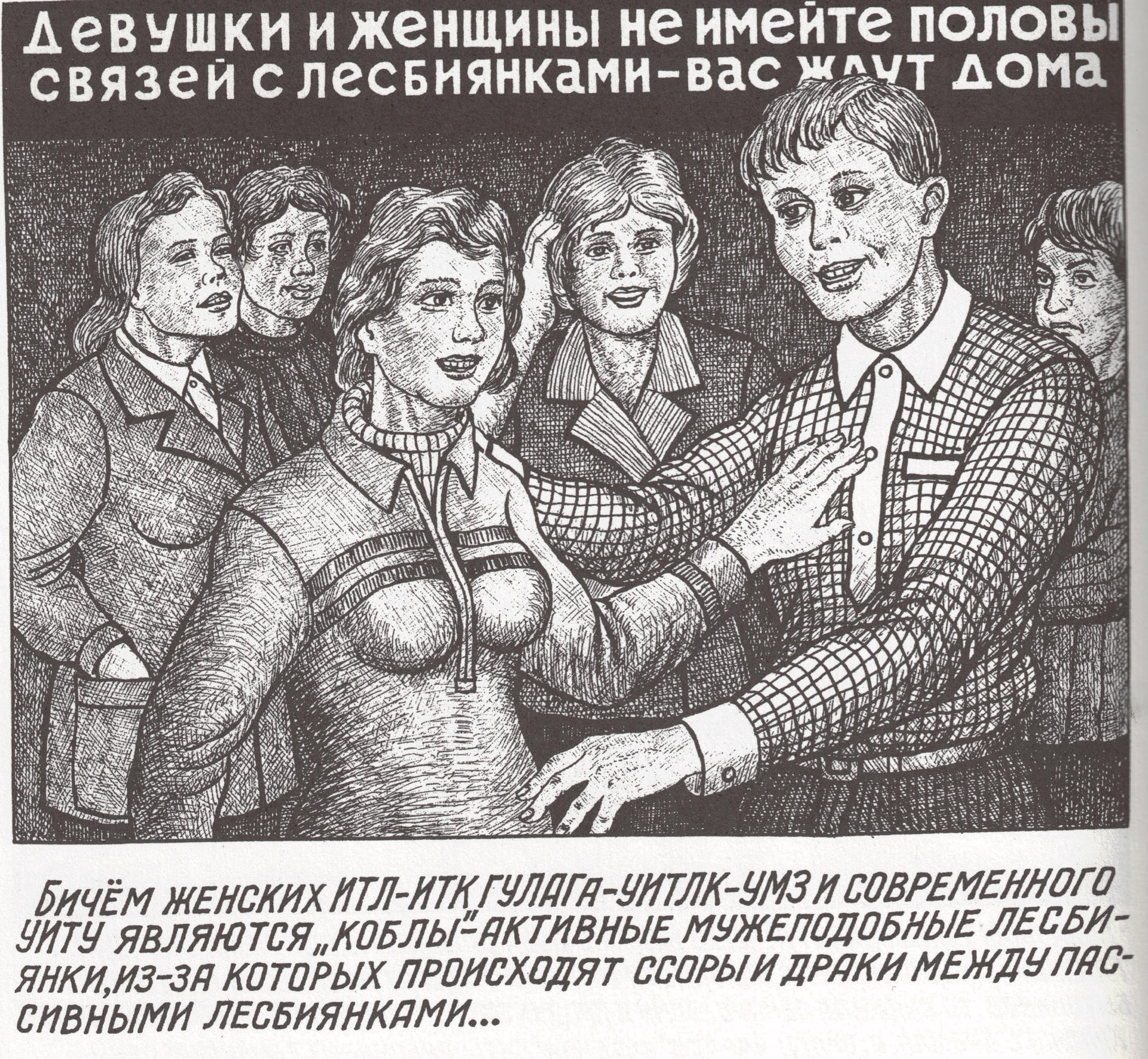

DANZIG BALDAEV, Drawing of a homophobic GULAG poster, The top reads : “Girls and women, do not engage in sexual affairs with lesbians! Someone is waiting for you at home“, published in the book ‘Drawings from GULAG. Danzig Badaev

Image

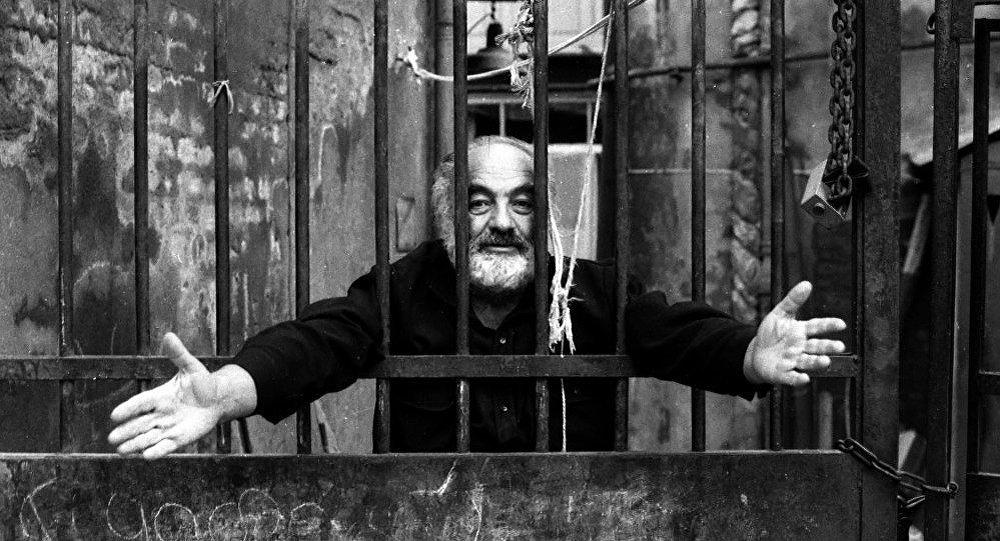

Director Sergei Parajanov, 1994, Public Domain

THROUGH 90s TOWARDS THE NEW CONSERVATIVE

The Perstroika and Glastnost’ let more fresh air in. That article 121 (consensual sexual relations between men and sodomy ) remained in power till 1993. When Yeltsin needed to look good for the EU and the world. Multiple international LGBTQIA organizations opened offices in Russia. The queer activism, discourses, press, just like at the beginning of the XX century were getting out of the closed underground community into the mass culture. Putin’s government took the course toward slow but steady movement towards conservative authoritarianism. I give up on this word in English. Such politics in combination with other repressive laws controlling education and free press a number had a number of consequences. As a result we have been deprived of big parts of the cultural memory and we continue denying it. Like Ballet Ruse never came to perform in Russia in 1920s, Sergei Eisenstein’s erotic drawing are still shown only in New York and London, not in Moscow, The Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam acquires works of earlier mentioned Yulia Tsvetkova (2020), who is still facing six years in prison at home, David France makes a documentary Welcome To Chechnya, bringing attention to how the activists of the Russian non profit LGBT Network risk their life helping queer people escape from being tortured and murdered in the Republic Of Chechnya and it is not shown in Russia.

Image

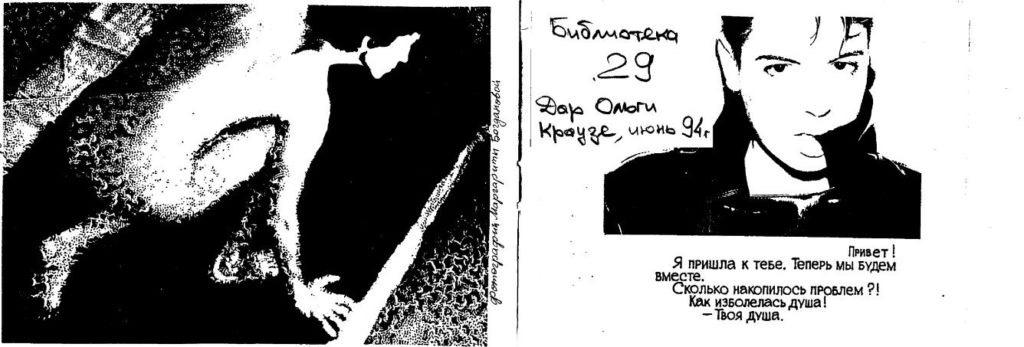

Illustration in the magazine, Probuzhdenie/Awakening, 1994-1995

A psychologist and a historian Elena Mis’kova who works with generational memory and trauma emphasizes the importance of grieving, having an open historical discussion, talking it out. Stalin’s regime and GULAGs as the birthplace of contemporary homophobia has never been fully processed. Russians are still nit sure how to process and remember what happened in 1930s-1980s. Addressing the past traumas and mistakes is becoming harder and harder with the closing of the archives, and the new legislation that prevents historians and activists from talking about it and general tendency to Stalin’s reglorification. The discussion of the historic and cultural heritage of LGBTQIA people (similarly to the discussions of any other topic that requires the government to admit mistakes) are dispersed and lay on the shoulders of a few NGOs, which is constantly interrupted by the Duma spitting out the new Orwellian laws.

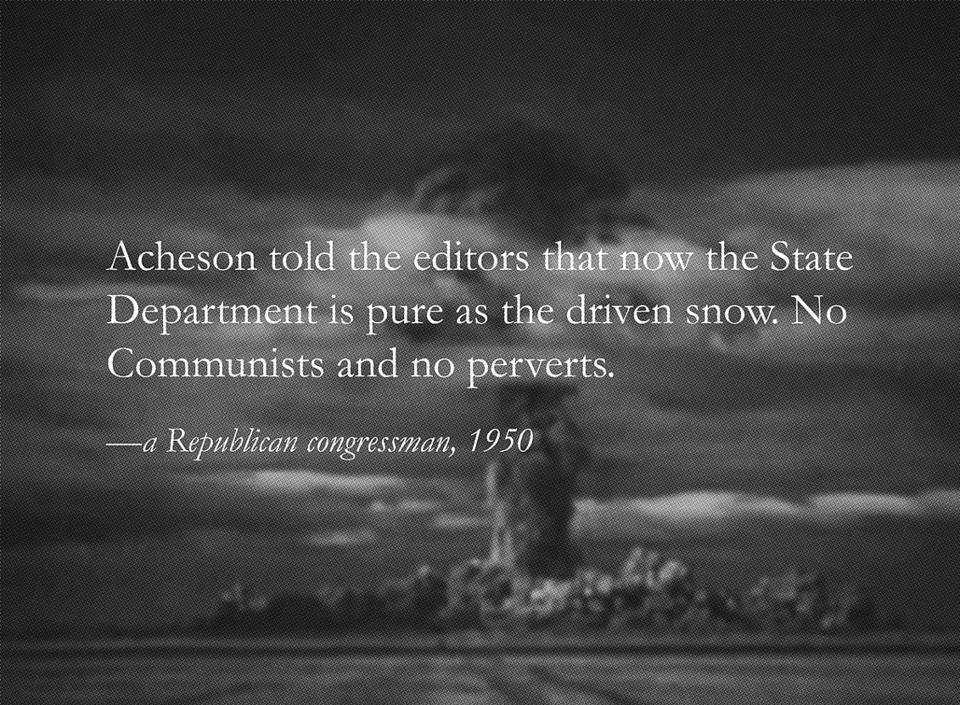

YEVGENIY FIKS, Stalin’s Atom Bomb a.k.a. Homosexuality No. 5, Giclee print, 2012, 55 × 76 cm, artist’s website, https://yevgeniyfiks.com

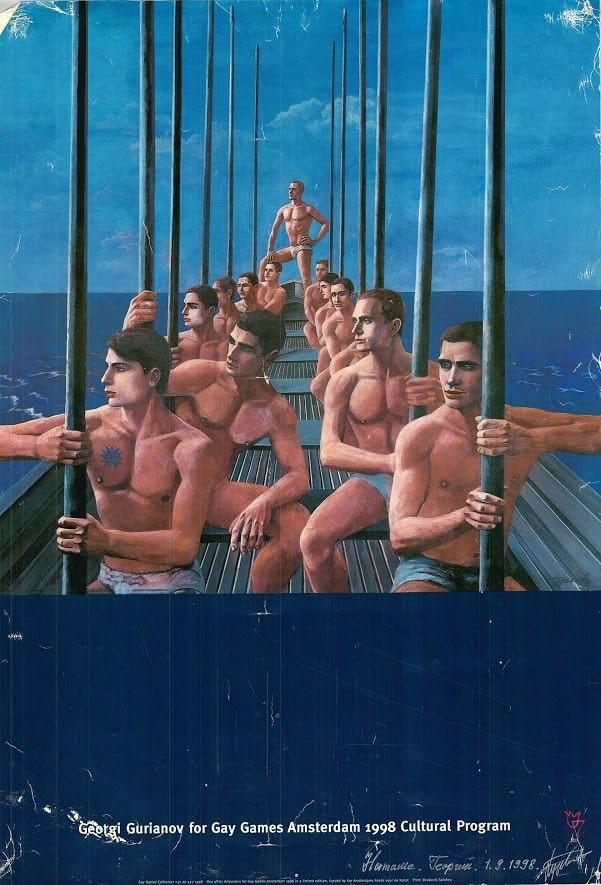

GEORGY (GEORGIY) GURIANOV, painting and poster for Gay Games Amsterdam, 1998, 148 x 148cm, Rotterdam Private collection & Sotheby’s

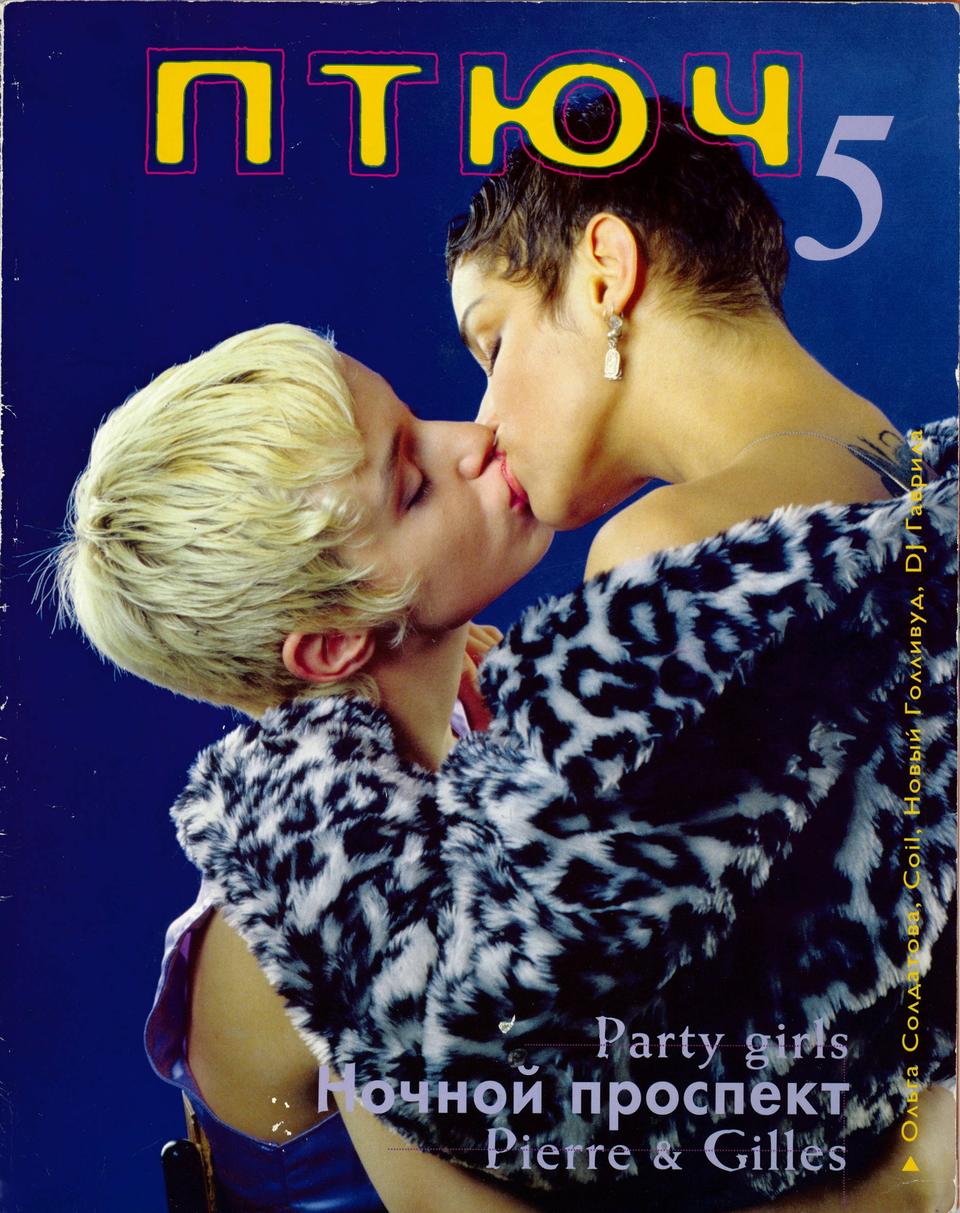

PTUCH, Magazine Cover #5, 1995, https://ptuch.org

SINIE NOSI/THE BLUE NOSES GROUP, An epoch of clemency, C-print, 2005, 100 x 130 cm, Diehl Gallery Berlin

Video file

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Attwood, Lynne. L. The New Soviet Man and Woman: Sex – Role Socialization in the USSR. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988

- Baer, B. Other Russias: Homosexuality and the Crisis of Post-Soviet Identity. Place of publication not identified: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- ——— and Klaus Kaindl. Queering Translation, Translating the Queer : Theory, Practice, Activism. New York, NY: Routledge, 2018.

- Bonnett, Alastair. The Idea Of The West Book. NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Brandist, Craig. The Dimensions of Hegemony: Language, Culture and Politics in Revolutionary Russia. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016.

- Burgin, Diana Lewis. Sophia Parnok: the Life and Work of Russia’s Sappho. New York: New York University Press, 1994.

- Cohen, Aaron J. Imagining the Unimaginable: World War, Modern Art, and the Politics of Public Culture in Russia, 1914-1917. Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2008.

- Costlow, Jane T. Sexuality and the Body in Russian Culture. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford Univ. Press, 1993.

- Dziewańska, Marta. Post-Post-Soviet?: Art, Politics Et Society in Russia at the Turn of the Decade. Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2013.

- Duberman, Martin B., Martha. Vicinus, and George. Chauncey. Hidden from History : Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian past. New York, N.Y.: NAL Books, 1989.

- Edmondson, Linda, Davies, R. W, and Rees, E. A. Gender in Russian History and Culture. Studies in Russian and East European History and Society. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2001.

- Engelstein, Laura. The Keys to Happiness: Sex and the Search for Modernity in Fin- De-Siècle Russia. New York: ACLS History E-Book Project, 2005.

- ———. “Soviet Policy Toward Male Homosexuality.” Journal of Homosexuality 29, no. 2-3 (1995): 155-78.

- Engström, Maria. Russian Queer Art Communities (1980s and 1990s): Timur Novikov’s New Artists and New Academy, 2018.

- ———. “From Sexual Revolution to ‘Sexual Sovereignty’: Queer-Art Exhibitions in Post- Soviet Russia,” 2017. https://doi.org/https://www.academia.edu/35193972.

- Fejes, Nárcisz, Fejes, Nárcisz, and Balogh, Andrea P. Queer visibility in Post-socialist cultures. Vol. 48419. Bristol: NBN International, 2013.

- Flegon, A. Eroticism in Russian Art. London: Flegon Press, 1976.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: The Will to Knowledge. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

- ———. The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: the Use of Pleasure. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

- ———. The Care of the Self: Volume 3 of The History of Sexuality. New York: Vintage Books, 1988.

- Gerard, Kent., and Gert. Hekma. The Pursuit of Sodomy : Male Homosexuality in Renaissance and Enlightenment Europe. New York: Harrington Park Press, 1989.

- Gessen, Masha. The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia. New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2017.

- Gippius, Z. N., and Temira Pachmuss. Between Paris and St. Petersburg : Selected Diaries of Zinaida Hippius. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975.

- ———. Contes d’Amour. Dnevniki Liubovnykh Istorii. Gippius. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://gippius.com/doc/memory/contes-d-amour.html#2.

- Golubev, Pavel Sergeevich. Konstantin Somov : Dama, Snimaiushchaia Masku. Ocherki Vizualnosti. Moskva: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, 2019.

- Grois, Boris. The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Healey, Dan. Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: the Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- ———. Bolshevik Sexual Forensics: Diagnosing Disorder in the Clinic and Courtroom, 1917-1939. Northern Illinois University Press, 2009.

- ———. Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi. Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2018.

- Jonson, Lena. Art and Protest in Putin’s Russia. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- ——— and Andrej Vladimirovič Erofeev. Russia - Art Resistance and the Conservative-Authoritarian: Zeitgeist. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Karlinsky, Simon. The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolai Gogol. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- ———. Marina Tsvetaeva : The Woman, Her World, and Her Poetry. Cambridge Studies in Russian Literature. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Kon, Igor Semenovich. The Sexual Revolution in Russia: from the Age of the Czars to Today. New York: Free Press, 1995.

- Levin, Eve. Sex and Society in the World of the Orthodox Slavs: 900-1700. New York: Cornell Univ. Pr., 1989.

- Levitt, Marcus C., and A. L. Toporkov. Eros and Pornography in Russian Culture. Moskva: Ladomir, 1999.

- Lord, Catherine, and Richard Meyer. Art and Queer Culture. London: Phaidon, 2019.

- Mole, Richard C. M. Soviet and Post-Soviet Sexualities. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 90. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

- Moss, Kevin. Out of the Blue : Russia’s Hidden Gay Literature : An Anthology. San Francisco, Calif.: Gay Sunshine Press, 1997.

- O’Donnell, Katherine, and Michael O’Rourke. Queer Masculinities, 1550-1800: Siting Same-Sex Desire in the Early Modern World. Basingstoke England: Palgrave Macmillan 2006.

- Poznansky, Alexander. Petr Chaikovskiai : Biografiia. Sankt-Peterburg: Vita Nova, 2009.

- Quenoy, Paul Du. Stage Fright: Politics and the Performing Arts in Late Imperial Russia. University Park: Penn State Univ Press, 2012.

- Reed, Christopher. Art and Homosexuality: a History of Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Richardson, Diane, and Steven. Seidman. Handbook of Lesbian and Gay Studies. London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE, 2002.

- Ross, Janice. Like a Bomb Going off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015.

- Sperling, Valerie. Sex, Politics, and Putin: Political Legitimacy in Russia. Oxford Studies in Culture and Politics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Stella, Francesca. Lesbian identities and everyday space in contemporary urban Russia. Glasgow: Glasgow University, 2009.

- ———. Lesbian Lives in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia: Post/Socialism and Gendered Sexualities. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Strukov, V. “The Queer Coat: Konstantin Goncharov’s Fashion, Russian Masculinity and Queer World Building.” 2019, 81-102. ISSN 2050-070X.

- Summers, Claude J. Gay and Lesbian Literary Heritage. 2nd ed. Florence: Routledge, 2002.

- Tchelitchew, Pavel. Pavel Tchelitchew : An Exhibition Catalog in the Gallery of Modern Art, 20 March through 19 April 1964. Foundation for Modern Art, 1964.

- Timm, Annette F., and Joshua A. Sanborn. Gender, Sex and the Shaping of Modern Europe : A History from the French Revolution to the Present Day English ed. Oxford ; New York: Berg, 2007.

- Tyler, Parker, and Pavel Tchelitchew. The Divine Comedy of Pavel Tchelitchew : A Biography. Fleet Pub. Corp., 1967.

- Benois, Alexandre. Moi Vospominaniia. Nauka, 1990.

Russian Sources

- Bogomolov, N. A. Mikhail Kuzmin: Stati i Materialy. Moskva: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, 1995.

- Golubev, Pavel Sergeevich. Konstantin Somov: Dama, snimaiushchaia Masku. Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2019.

- Golod, S. I., and Institut Sotsiologii . Sankt-Peterburgskii Filial. XX Vek I Tendentsii Seksualnykh Otnoshenii v Rossii. Sankt-Peterburg: Aleteiia, 1996.

- Firsov, B. M. Raznomyslie v SSSR i Rossii (1945-2008): Sbornik Materialov Nauchnoi Konferentsii, 15-16 Maia 2009 Goda. Sankt-Peterburg: Evropeiskii universitet v Sankt-Peterburge, 2010.

- Kon, Igor Semyonovich. Lunnii Svet Na Zare. Liki I Maski Odnopoloi Liubvi. Moskva: ACT, Olimp, 2003.

- ———. Muzhskoe Telo V Istori Kul’turi. Mokva: Slovo, 2003.

- ———. Seksualnaia Kultura v Rossii: Klubnichka Na Berezke/Sexual Cuture in Russia. Moskva: Vremia, 2010.

- Levitt, Marcus C., and A. L. Toporkov. “Elementi ‘Porno’ V Narodnoi Russkoi Kul’Ture Karelii.” In Eros and Pornographiia V Russkoi Kulture. Moscow: Ladomir, 1998.

- Khoroshilova, Olga. Molodye I Krasivye: Moda XX Godov. Bookmate. Moskva: Ėterna, 2012. https://bookmate.com/reader/oy3dQ8rx?resource=book.

- ———. Russian Travesti/ Russkie Travesti V Istorii Kulture I Povsednevnosti . Moskva: Mann, Ivanov i Ferber, 2021.

- Klejn, Leo. Neobychnaia Liubov VydaiuschiksiaLuid’ei: Rossiiskoe Sozvezdie. St.Peterburg: Folio Press, 2002.

- ———. Drugaia Liubov: Priroda Cheloveka i Gomoseksualnost’. St Petersburg: Folio Press, 2000.

- Khoroshilova, Olga. “First Travesti Of The Revolutionary Petrograd/ Первые Травести Революционного Петрограда.” Arzamas. Arzamas, February 20, 2019. https://arzamas.academy/mag/166-queer.

- Klesh, A. Istoriia Russkoi Gomoseksual’nosti Do I Posle Oktiabr’skoi Revoliutsii: Razlichnye Podhody I Prespektivy v Kak My Pishem Istoriiu. Ed. Grégory Dufaud, Liudmila Pimenova, Giom Garreta. Moskva, 2013.

- Matich, Olga. Eroticheskaia Utopia: Novoe Religioznoe Soznanie I fin de siècle V Rossii. Moskva: NLO, 2008.

- Morev, G. A. Mikhail Kuzmin i Russkaia Kultura XX Veka: Tezisy i Materialy Konferentsii 15-17 Maia 1990 g.Leningrad, 1990.

- Pushkareva, Natalia. A Se Grekhi Zlye, Smertnye: Liubov, Erotika I Seksual’naia Etika V Doindustrial’noi Rossii (X - Pervaia Polovina XIX v.). Moskva: Ladomir, 1999.

- Seks I Erotika v Russkoi Traditsionnoi Kulture. Russkaia Potaennaia Literatura. Moskva: Nauchno-izd. Tsentr “Ladomir”, 1996.

- “Seksual’nii Suverenitet Rodini Kak Novaia Vneshniaia Politika Rossii.” Republic. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://republic.ru/posts/l/980570.

- Sultanova, Gulia, Menni De Guer, eds. Nasha Istoriia. Zametki I Ocherki o LGBT v Rosii. Bok o Bok, 2018.

- “The Unmaking of a Man: The Life of Alexander Alexandrov and the Afterlives of Nadezhda Durova,” March 10, 2021. https://reees.macmillan.yale.edu/unmaking-man-life-alexander-alexandrov….

- Kuzmin, M. A., N. A. Bogomolov, and S. V. Shumikhin. Dnevnik 1905-1907. Sankt-Peterburg: Izd-vo Ivana Limbakha, 2000.

- Ushakin, Sergei. O Muzhe(N)stvennosti. Moskva: Novoe Literature Obozrenie, 2002.

- Zarubina, Tatiana. Gomoseksual’naia Subkul’tura v Dorevoliutsonnom Peterburge.” Arzamas. Arzamas, December 23, 2019. https://arzamas.academy/materials/635.

- Zdravomyslova, E. A., A. A. Temkina, and Evropeiskii Universitet v Sankt-Peterburge. Fakultet Politicheskikh Nauk I Sotsiologii. V Poiskakh Seksualnosti. Trudy Fakulteta Politicheskikh Nauk I Sotsiologii (Evropeskii Universitet v Sankt-Peterburge) ; Vyp. 3. Sankt-Peterburg: D. Bulanin, 2002.

- Zdravomyslova, E. A. Praktiki I Identichnosti : Gendernoe Ustroistvo : Sbornik Statei. Gendernaia Seriia. SPb.: Evropeiskii Universitet v Sankt-Peterburge, 2010.

- Zhuk, Olga. Russkie Amazonki: Istoria Lesbiiskoi Subkulturi v Rossii, XX vek. Moskva: Izd-vo “Glagol”, 1998.

- Zhrebkina, Irina. Strast’: Zhenskaia Seksual’nost’ V Rosii. St Petersburg: Aleteia, 2001.