Image

ARIEL WILLS

ABSTRACT

Can acts of making carry the memories of our embeddedness within the world? This thesis explores how making things can nurture a sense of kinship that cuts across the organic and inorganic, erasing the distinction between living and dead, material and spiritual. Through handwork such as art-making, sewing, knitting, cooking, woodworking, and beyond, the burden of remembering and of archiving is shared across human and non-human bodies, cultivated through practices of making, and through the materials themselves. By recounting the stories of my family’s experience as Jewish immigrants in the United States, I aim to reveal how their domestic practices of making allowed them to make memory tangible and curb the experience of loss. In these encounters, maker and material interact in communication. Their collective dialogue serves not only to remember the past but to remake memories for the future. By identifying such modes of memory-making beyond the mind, I challenge the purely psychological models of memory and the modern division between mind and body on which they rest. As such, this thesis is both a personal account and an invitation to acknowledge our deep and inherent kinship with the material world.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1. Sewing Memory: Doll Clothes and Other Selves

“Memory is fiction. We select the brightest and the darkest, ignoring what we are ashamed of, and so embroider the broad tapestry of our lives.”

― Isabel Allende

Chapter 2. Material Encounters: Kinship Across Beings

“The struggle of [people] against power is the struggle of memory over forgetting.”

—Milan Kundera

2.1 Form and Felting

2.2 Chicken Soup

Chapter 3. Dolls, Dreams, and Language

“The universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.”

—Thomas Berry

Chapter 4. Saks, Dresses, and Mnemonic Patterns

“You pile up associations the way you pile up bricks. Memory itself is a form of architecture.”

—Louise Bourgeois

Chapter 5. Broken Needles and Experienced Beginners

“Contrary to what I might like to think, my life is not guided by reason; it is ruled rather by the inertia of habitual motion.”

—Amitav Ghosh

5.1 Process and Play

Conclusion: Open Dialogues and Material Memory

Bibliography

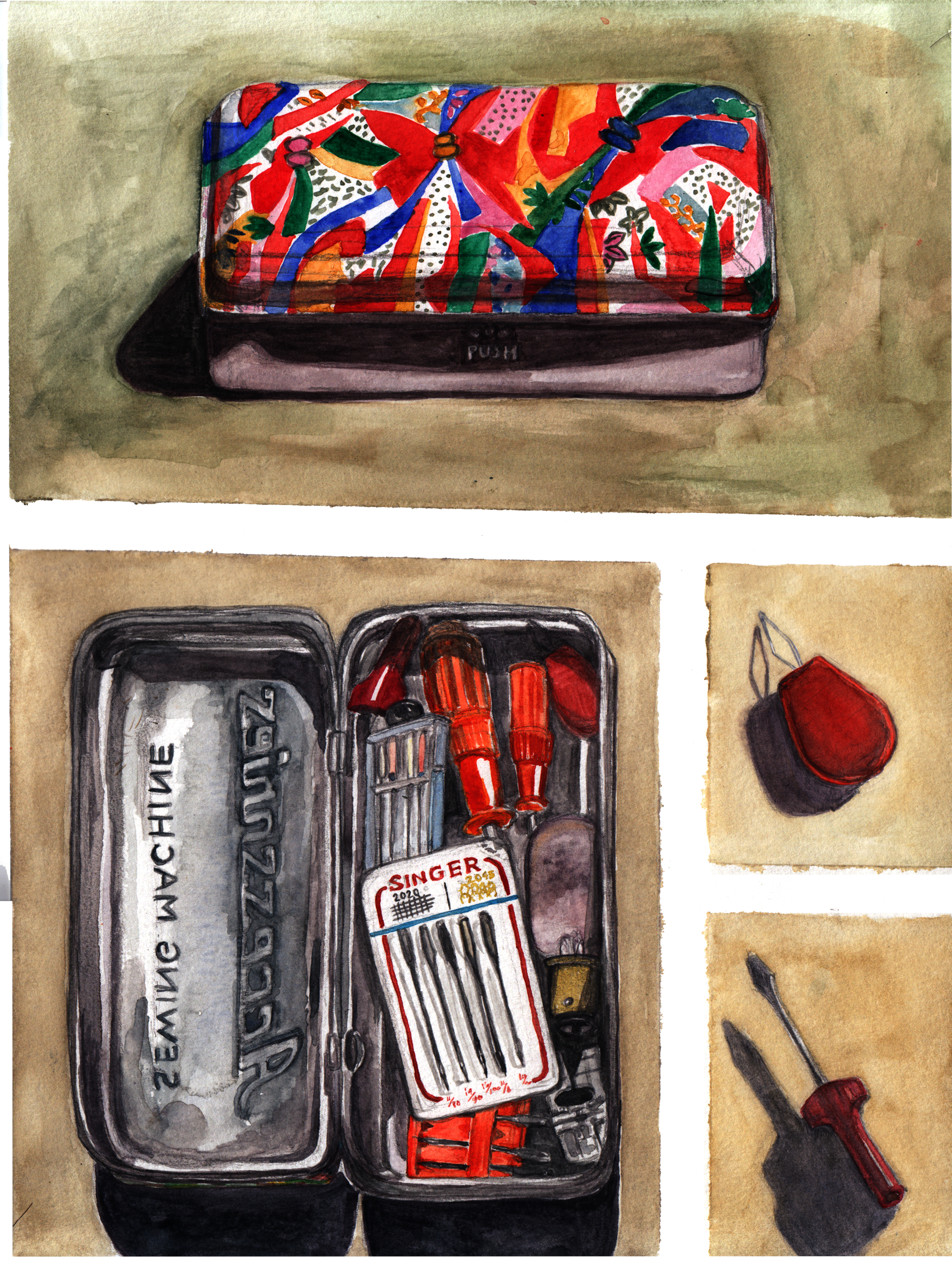

Image

▲ Sewing Machine Tools.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

The first garment my mom learned to make for the little fluffy-haired figures was a kimono. This is fairly straightforward because you only need one panel of fabric. There is not any three-dimensional construction the maker needs to consider ahead of time. She first told me these stories when she was teaching me to sew my first doll clothes, too. I remember being little and trying to imagine my great-great-grandmother sitting with my mom as a child, putting together a tiny kimono. I remember thinking how cosmopolitan their troll dolls must have been, wearing Japanese outfits in the middle of Los Angeles in the 60s. I learned later that fashion and textile traditions from Japan had a strong influence on style in the U.S. I found photos of my great-great-aunt, Ada, or Momsey as everyone called her, a Jewish Lithuanian Immigrant, wearing a kimono around the turn of the century. There are stories of her life as a “Floradora Girl,” a chorus line dancer in the Edwardian musical comedy on Broadway, and a participant in high fashion and the lifestyle of New York City society. As Valerie described, “I mean, that whole New York gangster thing going on in the 20s, you know . . . ” (Cooper 2020).

I grew up listening to stories of the Troll dolls and porcelain babies because my mom taught me to sew when I was very young, and so these stories were relatable to me. When I was as little as three years old, she would help me sew clothes, toys, and dolls, often out of wool felt, which is a dream to work with because it does not unravel like woven or knit fabric, making adjustments like adding extra fabric for the hem unnecessary. Sometimes, I paid close attention to stories my mom shared with me, while other times I let the words just flow over me, my focus intently secured on whatever I was working on and sewing. I will never have the first-hand experience of what it was like to grow up alongside those ancestors, but my stitches serve to fill gaps and empty spaces in my memories, from those days before I was born. Each stitch is an affirmation of perseverance, creation, and continuation. We are still here.

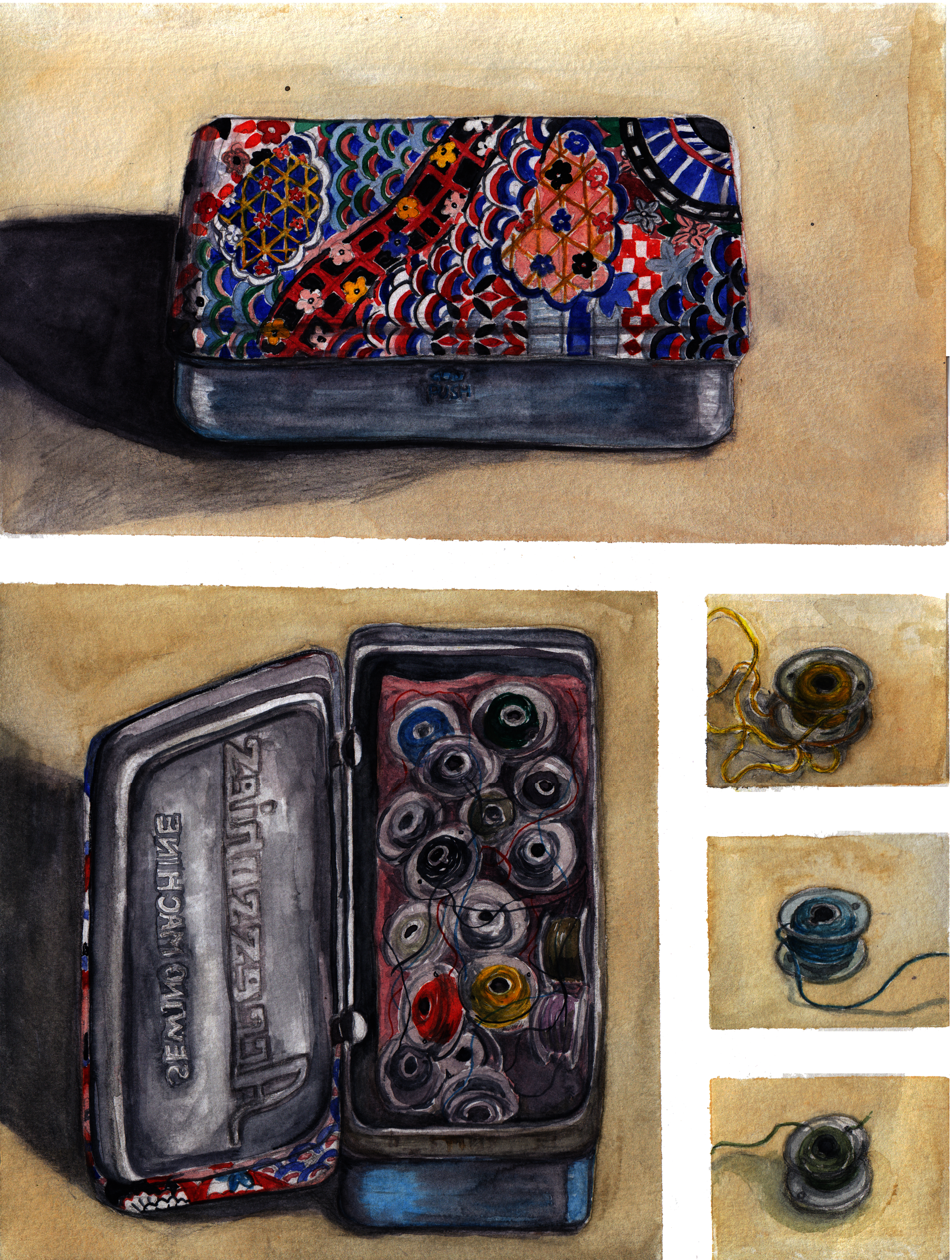

Image

▲ Nana's Bobbins.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

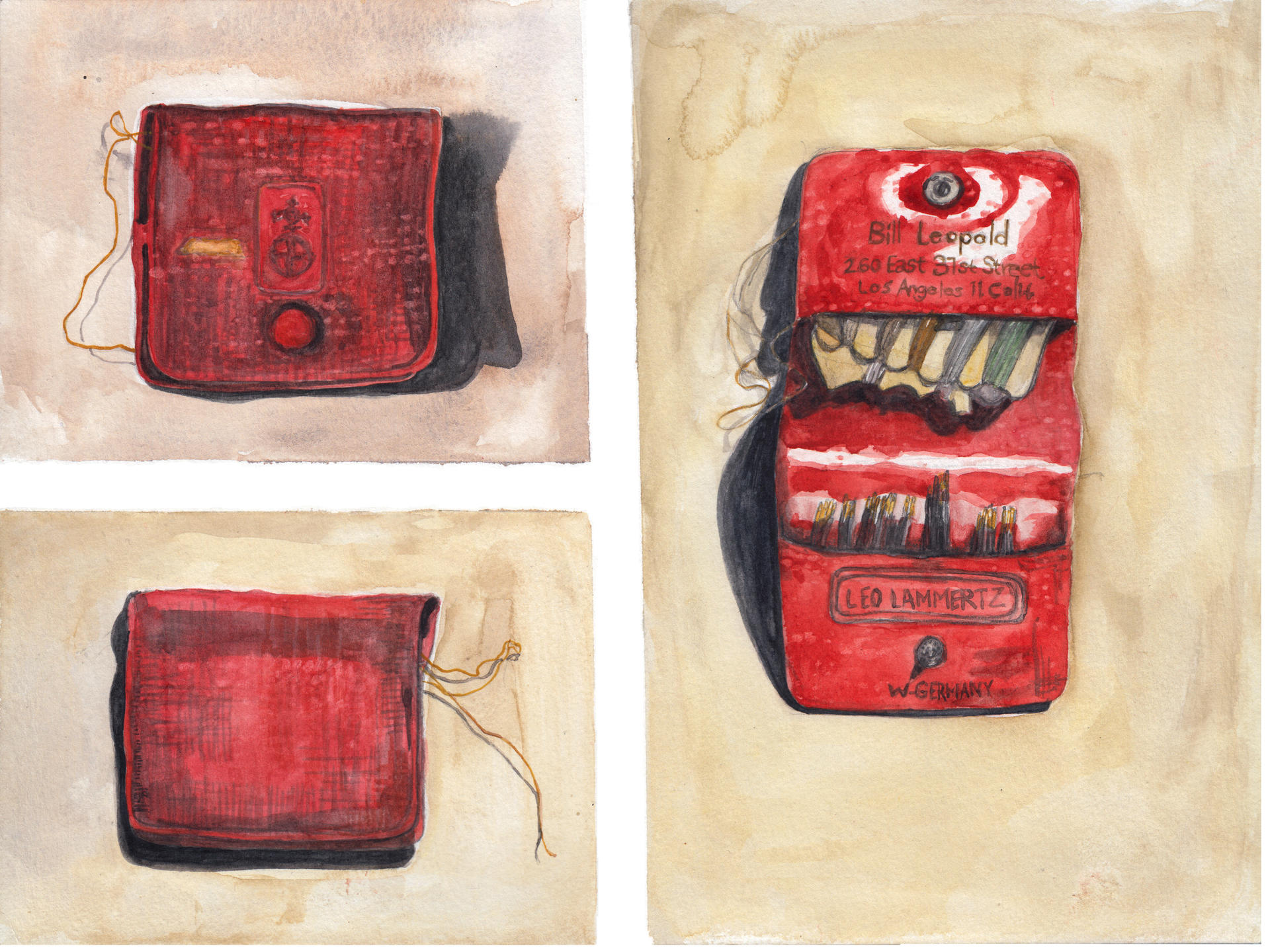

Image

▲ Bill Leopold Needle Case.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

Though I do not know details about my family’s life back in Vilna, I appreciate that my interests in textiles and fashion echo my family’s expertise and the way my ancestors interacted within their world. When people protect themselves from traumas by employing the coping mechanism of disconnection from one’s world, this can become habitual beyond the period of service. Often, this coping mechanism continues within the body past the time of peril when the disconnection is no longer protecting the human. As I wonder how to reconnect, I already have a sense of how tapping into the web of memory and practices of making could serve to reattune the individual to their place in the world. When I say memory, I mean one which is beyond the individual, an overarching memory we live within and might attune ourselves to, not some universal truth.

How might returning to practices like Mimi’s help us reimagine our relationship to the past and the future today? Might the handmade object communicate qualities of personal history and reinforce foundations of heritage to lead to a future of sustained cultural memory? What would a future of cultural sustainability mean and look like? I imagine a large-scale reattunement to the world. It would be an appreciation of the identity and belonging that are nested within the context of the greater world and extends beyond ourselves, which is nurtured through the knowledge that communities are inextricably included within this vast world. Where sewing, traces of my lost memories, the memories that never were, gain their own substance as material memories. Stories of the past are reanimated within my seam work. I have experienced an antidote to worldly disconnects in my practices of making.

Kohn (2013) details ways in which we are pulled out of relation to ourselves and each other every day, and sometimes we even kill this relation. Borrowing Cavell’s (2005, 128) phrasing, he calls these “little deaths” of everyday life. I was thinking of these little deaths as a kind of dissociation from self, to return to the tactic people use as self-protection from trauma. These little deaths appear in many contexts both superficial and profound, in “our slights of one another, in an unexpressed or disguised meanness of thought, in a hardness of glance, a willful misconstrual, a shading of loyalty, a dismissal of intention, a casual indiscriminateness of praise or blame – in any of the countless signs of skepticism with respect to the reality, the separateness of another” (Cavell 2005, 302). This makes me ponder how bringing awareness to the animism/vibrancy of things (Bennett 2010) might help us re-associate or connect to ourselves again. In bringing awareness to the vibrancy of things, perhaps we are actually bringing alive ourselves (in a counter-action to the “little deaths of everyday day life”) which is happening when we sew, cook, and do making practices. Therefore, by noticing the selves all around us, as the materials around us (carrot, knife, sleeves, thimble, doll clothes) and opening up to them as we work with them, we are becoming alive again, reconnected, and reattuned. Materials are selves. As traces of memory find a physical host within materials, the memory traces gain substance. Makers can, in a sense, “program” the thing we are making with residual memory as we follow the lead of the materials and the traces.

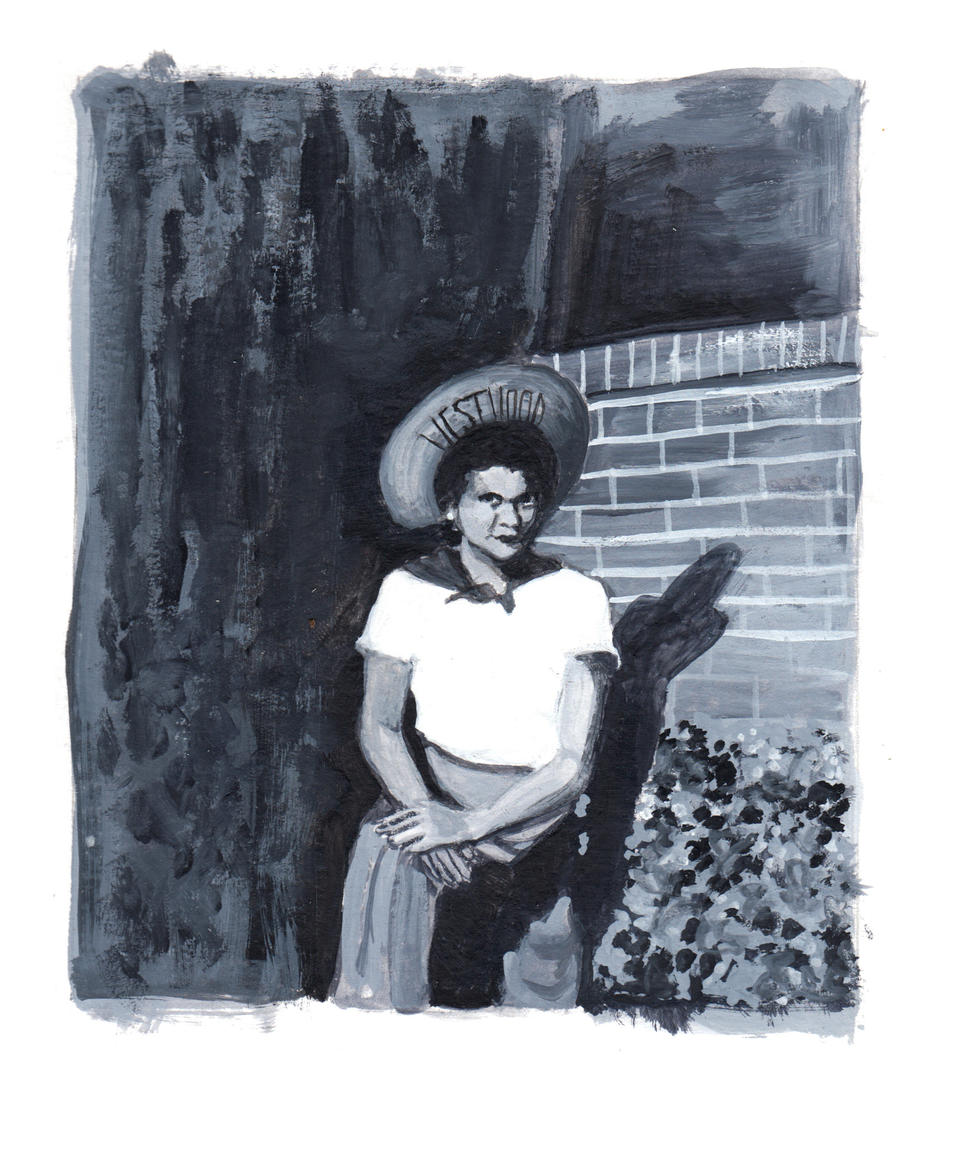

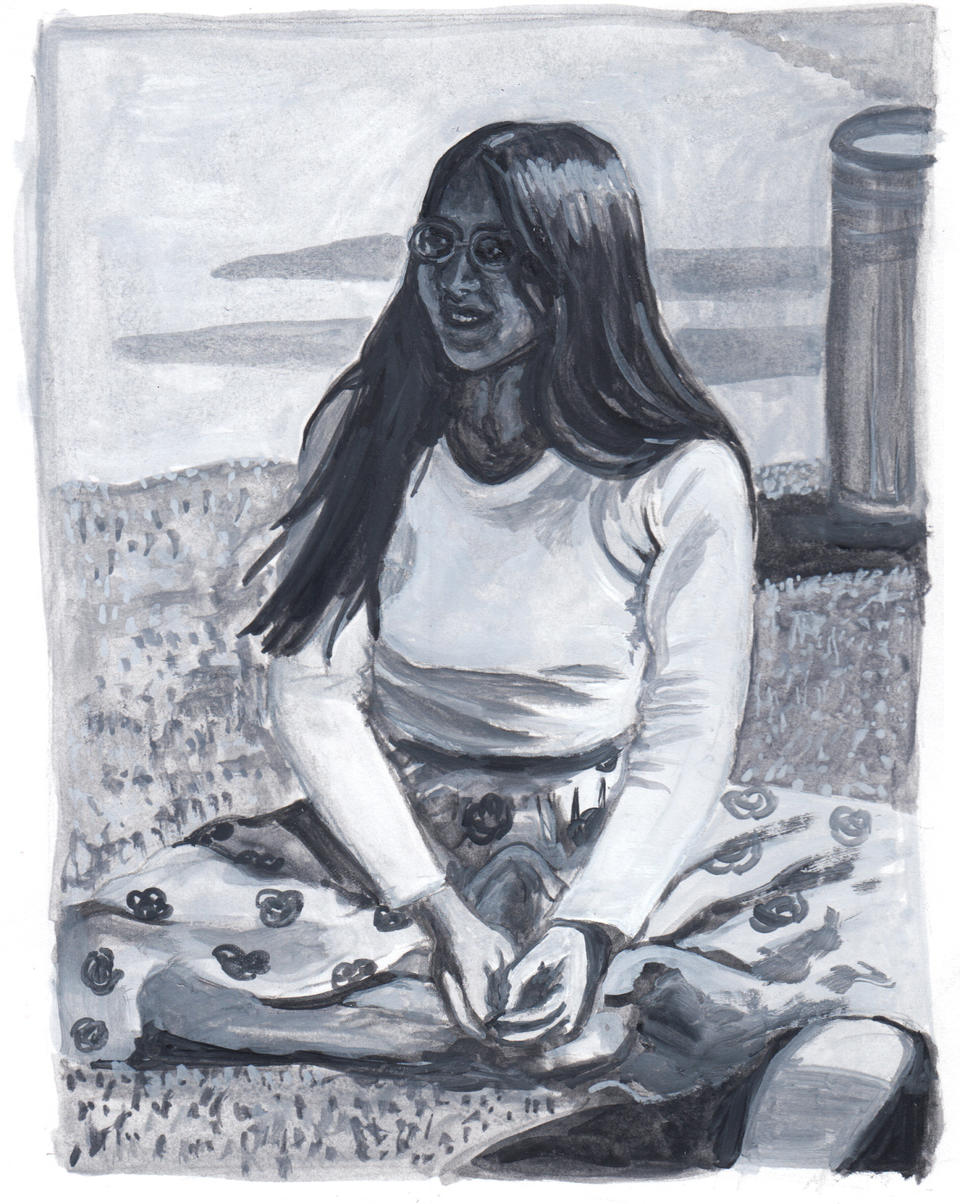

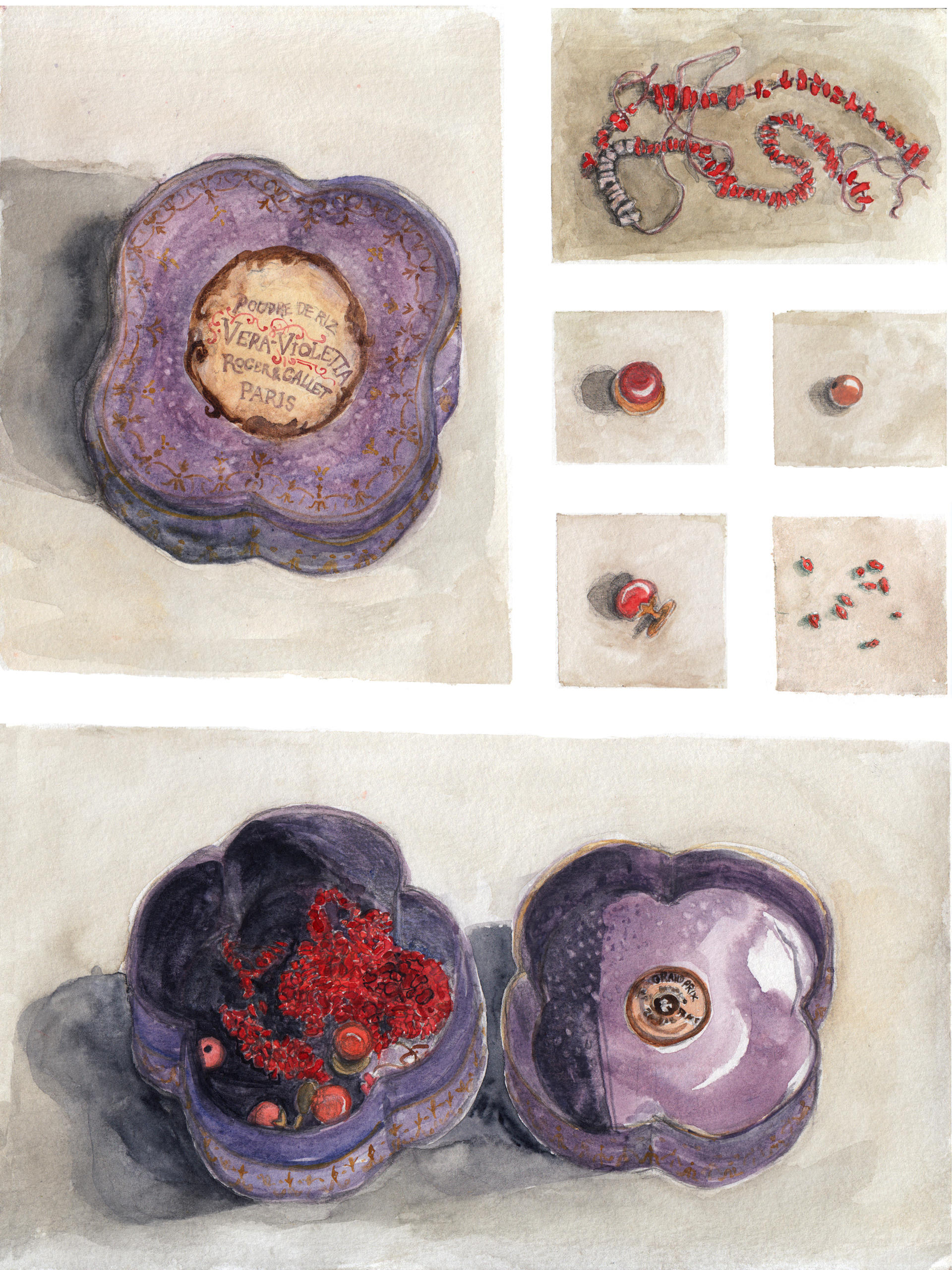

Image

▲ Vera-Violetta.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

By carrying out practices of making we start to glean how we are nestled in a web of beings and tangibles. Bennet enunciates the nonlinguistic expressivity of things, or “thing-power,” as marked by three defining characteristics (2010).

1. Slowness (the slowness of stuff). This is the comparative advantage of human flesh to the relative slowness of its rate of change in comparison to our own aging.

2. Porosity and contagion (Intercorporeality). Thing power works by exploiting a certain porosity intrinsic to any material body. A body is susceptible to collusion, interaction, collaboration and infusion with other bodies and any boundary is subject to change. We and all bodies (human and non-human) are inter-corporeal as we have membranes around us. This membrane does not always distinguish between another body. Bennet uses the example of hoarders to demonstrate these properties and to show how arbitrary the defining boundaries between people and things truly are.

3. Inorganic sympathy (strange attraction, neither useful nor aesthetic—advenient). This is a distinctive form of relationality and sympathy between things, as we generally assign types to them. Bennet explains this as how we do not think of things as able to act upon us or impact us but we do experience them that way.

“Materials do things to you physically,” says artist Kiki Smith (1994), who welcomes the variables and limits of the media with which she works. “Traditional materials do have heavy historical baggage. But they also have this physiological aspect: different materials have psychic and spiritual meaning to them. If you make bodies out of paper, or out of bronze, they have different meanings . . . You can make something in five different materials to have different emotional effects” (1994). Smith, who casts doll- and life-sized figures from bronze, wax, and papier-mâché, works with a variety of media including textiles and printmaking. In her practice, Smith considers the materiality of the human body along with the media she employs and what it means for the artist’s intentions to be embodied by materials. “Art is something that moves from your insides to the physical world, and at the same time it is just a representation of your insides in a different form. Art is just a way to think” (2003). I propose that beyond this, art is a way of thinking together, or thinking with materials.

Papier-mâché, for example, is easier to work with than wax and allows Smith to cut figures up and reassemble them, often returning to the same mold with different materials to cast in it. Multiple iterations of a figure cast from a single mold allow Smith to provide that figure with many lives, and as the character is repeated, “they get to have a life beyond just one version, they get to live again” (2003). Smith related how one such character, Genevieve, exists in many forms across Smith’s practice (bronze, wax, and papier-mâché). One of the Genevieve wax figures has greatly evolved over time, as Smith cuts her up again and again and reconfigures her to see how it goes, smoothing out the seams in the process. Though recasting an original piece would alleviate Smith of effort, she admits to enjoying the labor and the changes throughout each piece’s “lifetime,” “It would be much faster in a way just to cast another person and to redo it, but I do not know, it is just funny to me to have it all keep coming out of the same sculpture” (2003).

Smith follows the lead of the material as she works, allowing accidents and breakages to become part of the evolved final piece. “The more you manipulate it the more actual life you put into it” (2003). Influenced by the storytelling traditions of her Catholic upbringing, she considers her doll figures to exist across and beyond boundaries of reality and fiction, a realm that is full of surprises. “I will carry them around then I will break their leg off, you know, or their head gets knocked off or something but none of that is really seen in the end at all but to me that is really a big part about making it” (2003). Materials that have experienced coming apart then returning together will have an altered structural integrity. Though not always apparent to the viewer, the material holds the traces of disjuncture within its physicality, an embodied memory.

Image

▲ Nana's Thimbles.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

During my undergraduate degree, I found myself enchanted by my geology classes, originally selected to satisfy a science requirement, which then propelled my craving to explore geologic time. I was attracted to studying geology so I could go to the cliffy shores of the Oregon coast, an hour from where I lived at the time, examine the cliff sides, and read the land like a history book. As I studied patterns of stratification and learned to discern rock formations and tendencies surrounding different plate boundaries, I fine-tuned my perception until I could recognize indications of massive environmental movement, traces of volcanoes, bulging igneous formations, and consequences of shifting plate boundaries. Rock forms are tangible evidence of the physical fluctuations endured by the land. Rocks are a physical example of the memory of the earth, so does it matter whether it is alive? Either way, the earth is moving.

Oliver Sacks (1996) describes his fascination with the depth of ancient time and the magical moment he first saw living cycads, an ancient kind of seed plant with cones, at the Kew Botanical Gardens in London as a child. The fossil history of cycads (traces of memory in rocks) indicates their presence on earth from a time far beyond what our human mind can conceive. Though this ancient history is out of our reach mentally, perhaps by paying attention to the testimony given by materials who bore witness to this deep and ancient time, we can share in their memory. The cycad, descended from so long ago, embodies traces of memory within its genetic make-up, and every cycad that grows reiterates this history. “They too were survivors from a long-distant past, and the stamp of their ancientness was manifest in every part of them—in their huge cones, their sharp, spiny leaves, their heavy columnar trunks, reinforced like medieval armor, by persistent leaf bases” (Sacks 1996, 183). Sacks even describes a sort of “moral dimension” of the cycads, and the tragedy of plants growing out of synch with their “own dignified timescale,” yet the heroism of their perseverance through the destruction of the dinosaurs and even the employment of birds and mammals to disperse their seeds.

My stories of family and making reveal and expand understanding of both the traces we leave on the world and those that the world leaves on and within us. This world is made up of many selves who compose an ecology of life, including things that are apparently inanimate in the definition of life. Here I diverge from Kohn, and his questions of who is thinking together. I center in on traces of memory within the world of objects and materials, to which humans are a part of, for our bodies have materiality and are composed of billions of cells and a host of bacteria and microbiomes. I would like to recognize memory itself as a theory of life. Memory acts as a theory of life beyond the living, as a different way for us to think about life and our own existence within this ecology. I aim to expand memory as a theory of life for everyone. Memory is not just for living and dead. Memory is precisely the theory that does not make the distinction between organic and inorganic life or life and death. Everything has a memory and trace left within. Practices of making connect people to the world of tangible memory, and the exchange of residual memory from the fleshy human back and forth with materials reveals how we, as people, fit within the context of the world. This resolves anxiety of disconnection (misattunement) and heals perceived division between mind and body. People are material–our brains are always building neural pathways. When the human memory leaves a mark on the outer tangible world (the physical world that is beyond the ‘boundary’ of our skin) and the tangible world, in turn, leaves its trace on the human, the burden of remembering and of archiving is shared across human and material bodies, cultivated through practices of making, and through the materials themselves. ♦

1. Sewing Memory: Doll Clothes and Other Selves

“A stitch in time saves nine.” This saying was a reminder to be patient and attentive in my actions and especially to sew with focused diligence. Slowly and carefully working through the process and series of steps of preparing fabric, sometimes with an iron, tracing the pattern, and threading needles. These moments would prompt my mom to recall memories of working and sewing together with the women in the family when she was a little girl. For as long as I can remember, my mom has told me these stories when we make things together.

She had learned to sew from my great-great-grandmother Mimi, who always was busy taking care of the home. Mimi was very small, and incidentally had a collection of tiny dolls and miniature figurines made out of porcelain and Bakelite on the shelves above her built-in dresser. The little dolls sat up there on display behind glass cupboard doors, and my mom, as a child, could look but not touch. Mimi would create clothing for the tiny dolls, whose arms and legs were jointed, so they could don the miniature sweaters, sunsuits, and gowns she designed.

My mom reports that Mimi would knit with toothpicks while our cousin Valerie remembers her crocheting with pins to dress the little dolls in their own versions of the clothing that she would also make for the babies in the family (Cooper 2020). While the porcelain and Bakelite babies were fragile and out-of-reach of little hands, they were not the only dolls in the house that were dressed in a new wardrobe. Mimi taught both my mom and Cousin Valerie to sew by helping them make outfits for Troll dolls, plastic dolls with big eyes and brightly colored nylon hair that sticks up like a flame of neon pink, blue, green, and so on. Valerie created a little business. She would design Troll doll clothing, sketching her ideas on paper. Mimi would help her sew them, then Valerie would bring the doll clothes to her elementary school and sell them to other children.

Image

▲ Mayfair Needle Case.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

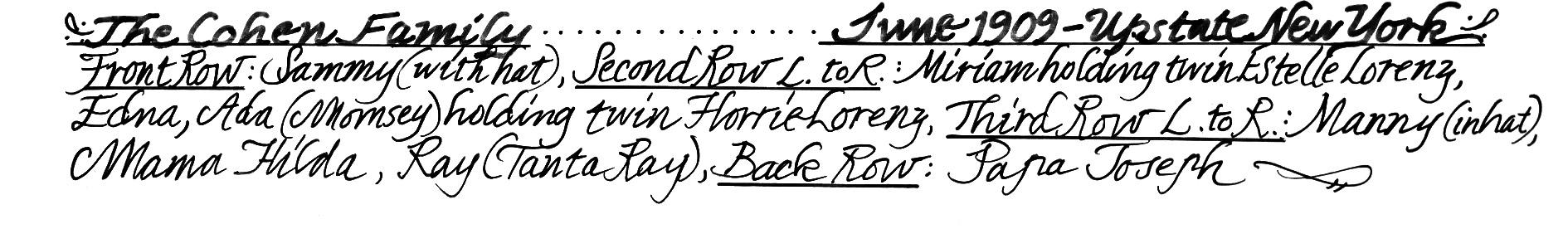

I feel a strong loss of heritage and familiar origin. We have emigrated from many places, over time, and spread ourselves out. I have a sense of many origin points, traces from times when rich cultural sensibility and foundation were embodied within a close community, saturated in histories, family legacies, and most foreign to me, a clear sense of our past. How did we get here, where do we come from? My knowledge of the violence, the pogroms, that drove us to leave our homes is distant and abstract. When the Cohens came to New York, after leaving Lithuania, they preferred not to speak about the old country. Valerie and my mom both would ask about Vilna, but Mimi always maintained, We are American.

Mimi and the older family members’ unwillingness to dig up stories of the past touches on common emotional coping mechanisms to move forward in life. It is fairly easy to understand how the displacement the Cohens experienced in fleeing a dangerous environment would be felt in the body as trauma. Dr. Mate (2017) explains how “the essence of trauma is the disconnection from the self.” Repression and dissociation can be understood as the body’s way of protecting and taking care of oneself, yet this develops a misattunement of self and the effects of this disconnection can lead to complex trauma. My interest here is not in diagnosing my ancestors, but in noticing how practices of making can serve to repair and reattune people within the greater context of belonging within the world. The unknown voids in my family history have a visceral effect on me, like a slow ache. This is part of why I am interested in this topic of how memory exists beyond the human mind.

When I was three, I was relaxed while listening to my mother’s stories of her childhood—I absorbed them without a sense of haste. Now that I am older, my sense of time and distance are more profound. I long to reattach to the origin point, to understand and to fill in the gaps in our family’s memories. Peering over my family tree, I feel a sinking in my stomach as too many households are cut short around 1945. Killed in the Holocaust. How is the space of memories filled when you do not know what happened? Or when nothing could happen, because a branch of the tree was cut short? As I return to stitching, my needle piercing the fabric reanimates what is hidden in my blood memory, reiterating movements and going through steps my grandmothers repeated. My muscles learn to execute the motions and retain them in muscle memory. My blood holds my DNA and the histories of my ancestry, a physical record, and perseverance of the past into the future. This is where I cultivate a space where what is unknown and what never will be can exist in the home I carry inside me. This is me, I am material. The repetition of my hand and the rhythm of my sewing machine create seams which grow and continue into endless possibilities—possibilities that comfortably coexist. The simplicity of this practice, so visually superficial, is pregnant with complexity and the weight of my questions. The networks of memories (forgotten and imagined) are multiplied each time I share my sewing and embroidery. Certain people might see the connection, too; after all, my mom is always sure to mention when my work reminds her of Mimi and her sisters.

Image

▲ My Watercolors.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

Image

▲ Nana's Bone Folders.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

Appadurai (1986) explains how following the trajectories of objects helps reveal information about the human condition, “It is only through the analysis of these trajectories that we can interpret the human transactions and calculations that enliven things. Thus, even though from a theoretical point of view human actors encode things with significance, from a methodological point of view it is the things-in-motion that illuminate their human and social context” (5). By considering the maker, technique, their materials, and the historical context, it seems a very human need to seek out thresholds of our understanding. The understanding of someone’s relationship with their world is built up out of stories. Might sewing be a way to make sense of a story? To filter a story? Through imagining how humans encode things with significance, why should it not also be the other way around? Things encode us with significance, as we are, ourselves, material.

Things bring meaning into our understanding of the physical world, as they are defined by their limits. When a person fashions a tool, it is created based on the qualities of the materials and the limits of those materials but also of the limits of the materials with which it shall be interacting. Different materials are used for different applications. When a knife is forged, the decision to use stainless steel, carbon steel, or even obsidian will depend on the intended purpose of the blade. The engagement with various materials and components of the physical world requires a certain degree of material literacy on behalf of the maker. Each material is sourced from somewhere in the web of stuff, and in using any material, the connection to that web of stuff is developed. Over time, people learn to carve wood, manipulate leather, and so on, and these are examples of thinking with materials. The lessons learned through creative interaction with materials (by craftspeople, artists, human agents) over generations have a direct influence on how current craft practices are done. In other words, the memories of these people are passed down, over a period larger than an individual’s lifetime.

This must also apply to innovative forms of production, as all earthly materials exist within the context of the planet, as do humans. The relationship between different materials or lack of materials is always viewed by the individual who will engage with them. Sometimes, the maker will act on them, but the materials act on the maker just as much, maybe even more than we can possibly know. Here is where we learn through play, curiosity, and listening, as tangible and intangible worlds emerge from each other. An ecology of social practices using that which is present includes the non-human components that are always involved. “In Edward Casey’s words, memory “is already in the world: it is in the reminders and reminiscences in acts of recognition and in the lived body, in places and in the company of others” (Keightley and Pickering 2012, 81).

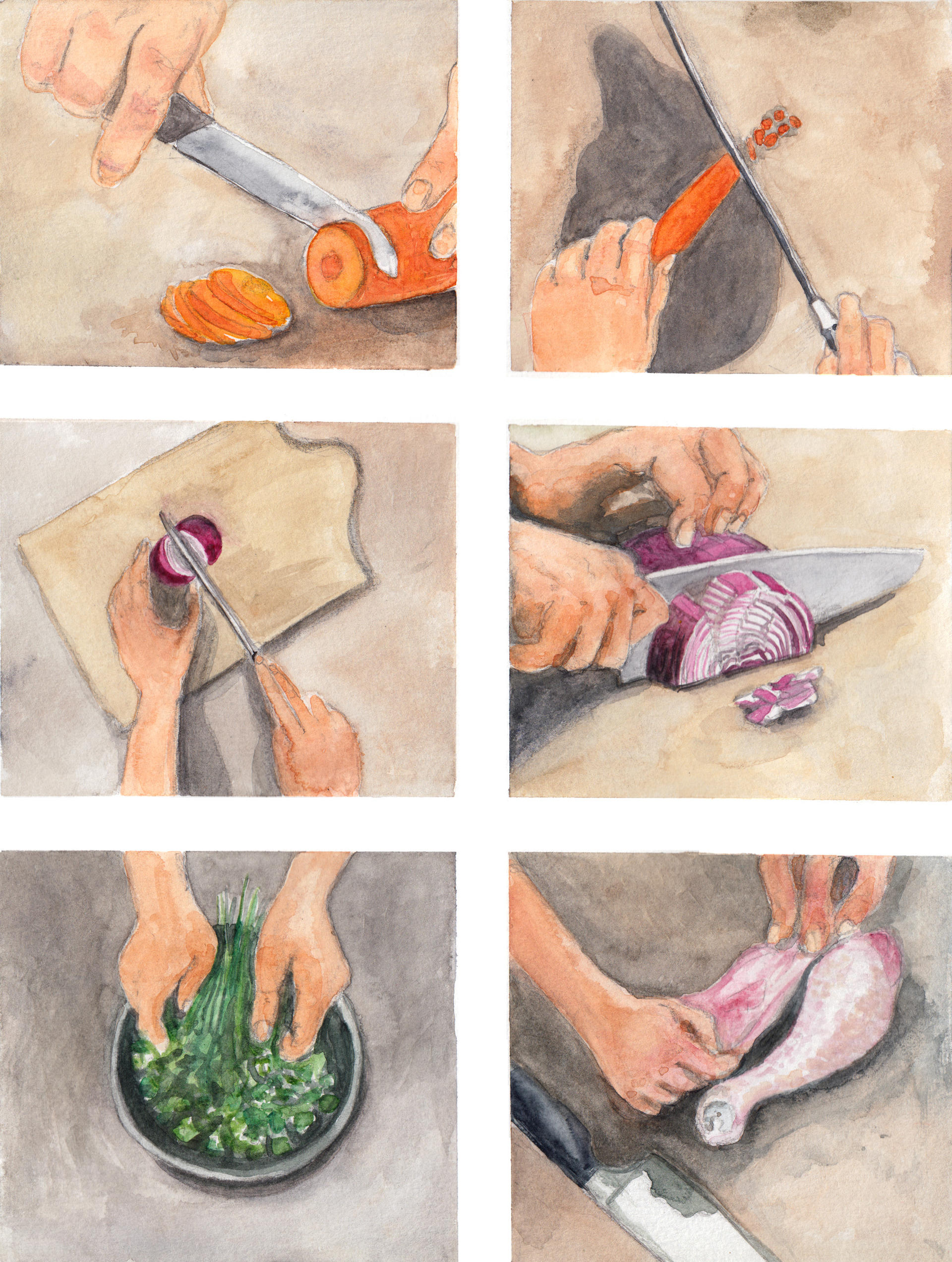

Image

▲ Preparing the Soup.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

Image

▲ Vegetables.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

In the following chapters, I will outline my theory of how memory is embodied in materials. This is proposed as an alternative model to thinking about memory in the Freudian and psychological sense. In contrast, memory that is embodied within material is not chronological nor permanent. Here, agency is distributed between the human self and the rest of the world and changes every time we remember it. We add to the memory every time we touch, sew, chop, pick, make, and remake something, and can do this across many practices of making. I will explore the question of how materials carry memory in their interactions with us, as humans. Should we acknowledge that materials hold traces of our interactions with them, then every time we make something we are engaging with these traces, and every remake of something is an act of archiving.

Should we understand trauma as a disconnection from the self, as Dr. Mate said, then how do making and memory mitigate that disconnection? People frequently carry objects as tokens of remembrance, so what role does the object’s origin have to play in its identity when it is being a keepsake? What if the role of memento is not imposed but inherent? The memento provides a window into our connection to objects, but I propose that it goes further than personal attachment to items or superficial materialism. There is a body of knowledge we ignore precisely because it is bodily and material, beyond the world of the mind, or how the mind sees the world.

If life and living thoughts could be distinguished because “life thinks; stones don’t” (Kohn 2013, 100), then what is there to be said about water that becomes a bay versus that which becomes a river? In Chapter 3, “Dolls, Dreams, and Language,” I demonstrate how changing the relationships between words enables humans to understand some context of the world beyond ourselves. As we discuss a “body of knowledge,” yet disregard materials and selves that are brainless, what are we missing?

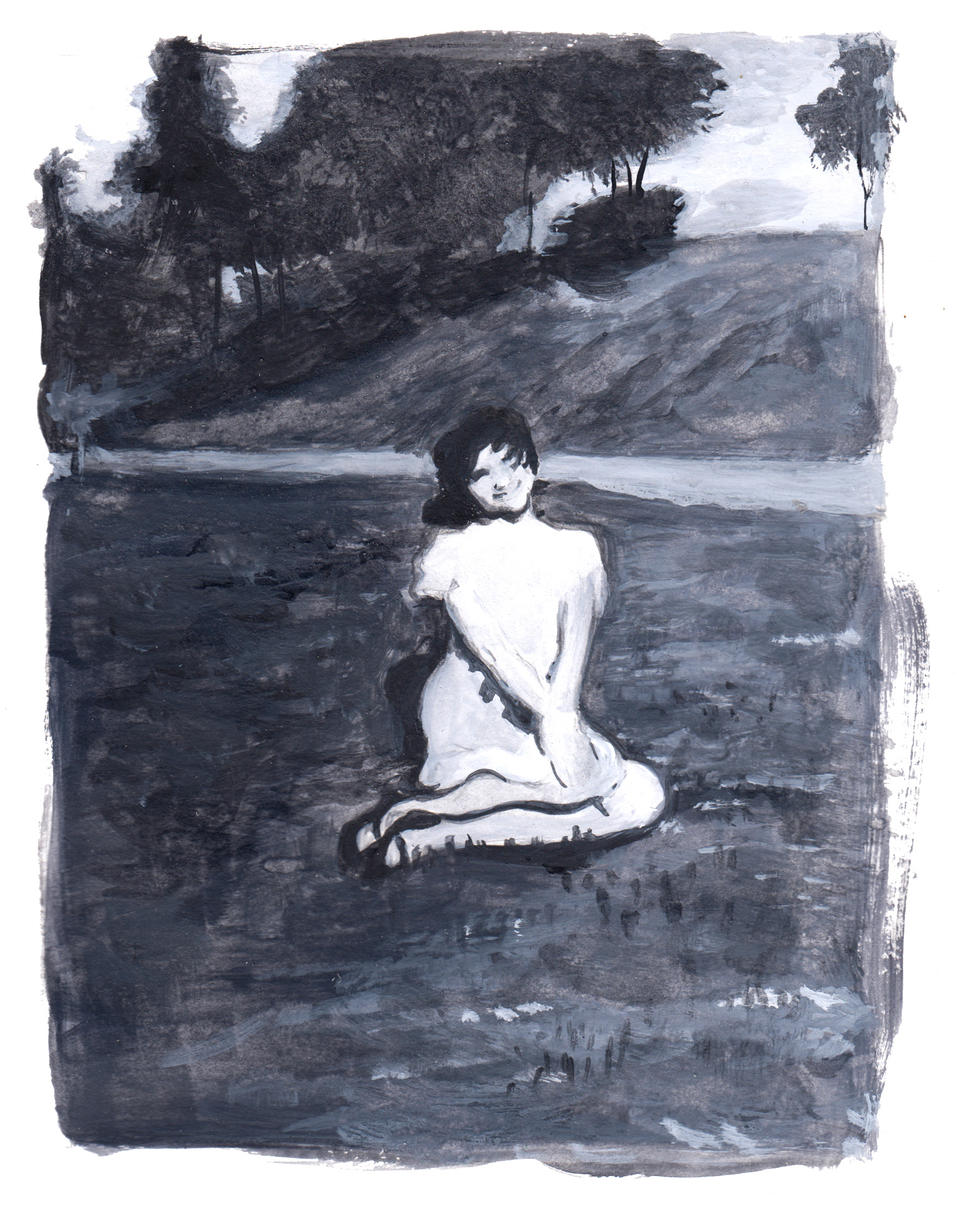

Image

Image

▲ The Cohen Family.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

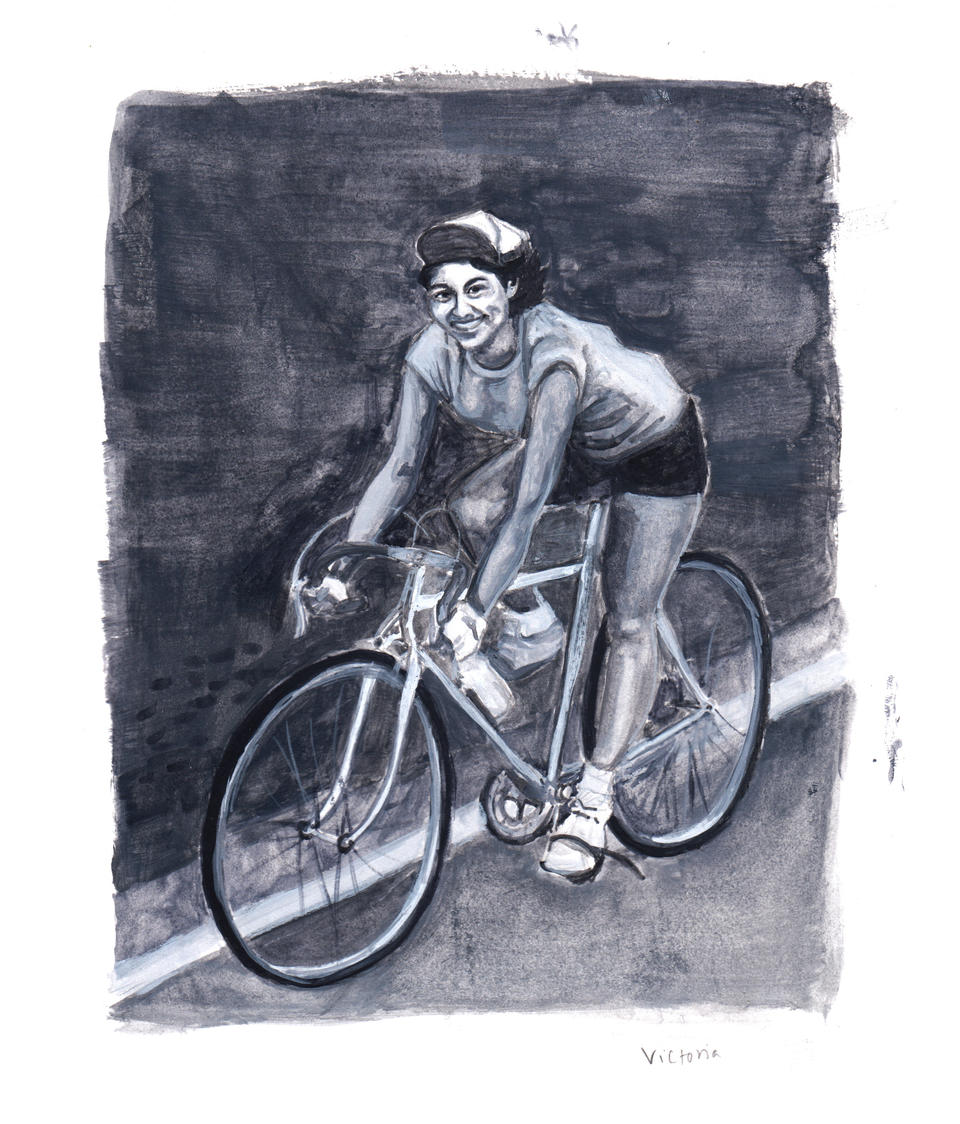

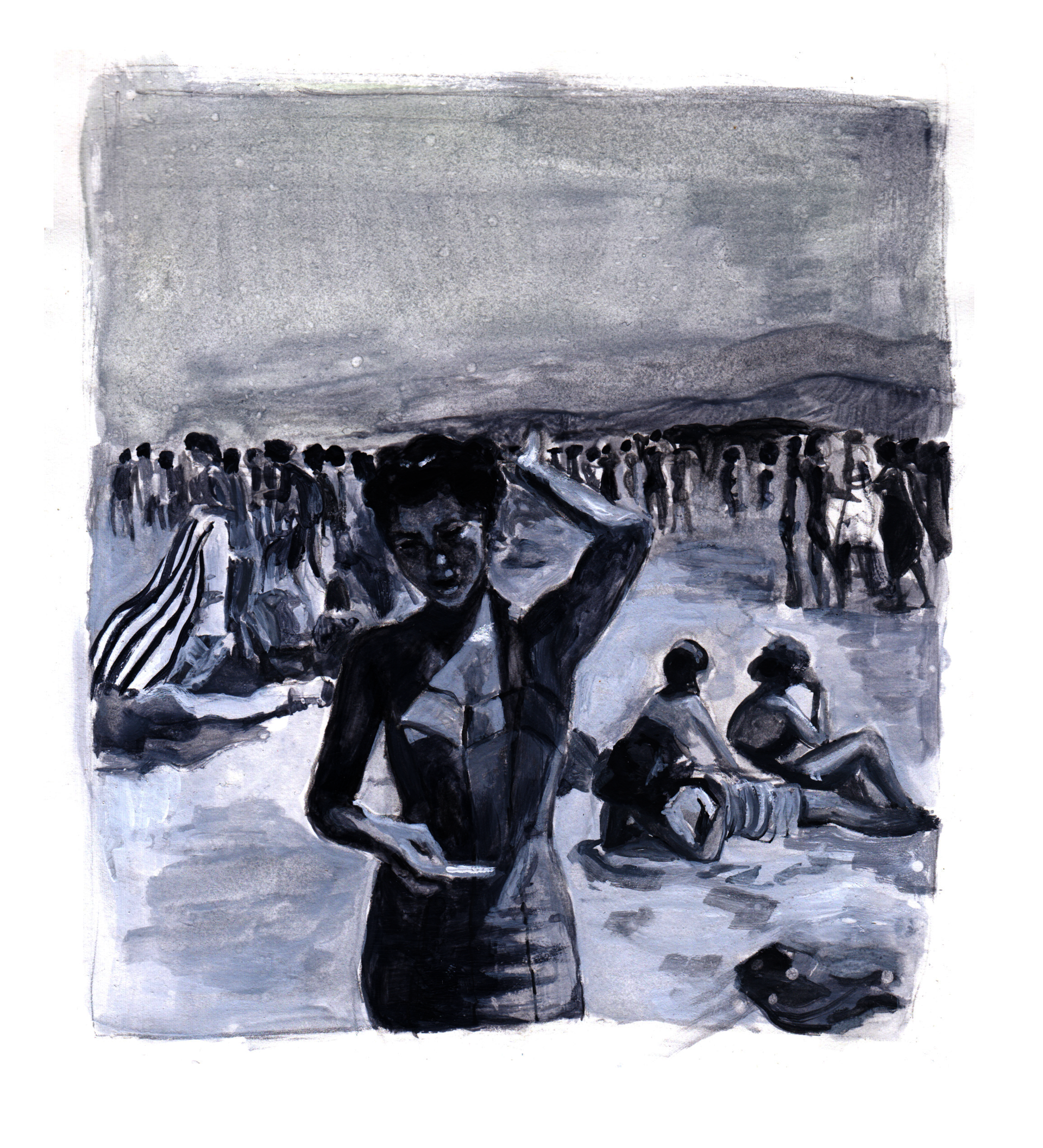

Image

▲ Photos of Nana.

2021, watercolor on coldpress paper, 9"x12"

Image

Image

BIBILOGRAPHY

Allende, Isabel. 2006. Portrait in Sepia. Translated by Margaret Sayers Peden. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Appadurai, Arjun., ed. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Baxmann, Inge. 2009. “At the Boundaries of the Archive: Movement, Rhythm, and Muscle Memory. A Report on the Tanzarchiv Leipzig.” Dance Chronicle 32, no. 1 (February): 127-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01472520802690333.

Bennet, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Berry, Thomas. 2006. Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on Earth as Sacred Community. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books & University of California. 149.

Bissell, Bill, and Linda Caruso Haviland, eds. 2018. The Sentient Archive: Bodies, Performance, and Memory. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Bourgeois, Louise. 1999. Louise Bourgeois: Memory and Architecture. Madrid, Spain: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

Cavell, Stanley. 2005. Philosophy the Day after Tomorrow. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 302.

Cooper, Valerie. 2020. Interview by author. Providence, RI and Malibu, CA. October 31, 2020.

Derrida, Jacques, and Eric Prenowitz. 1995. “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.” Diacritics 25, no. 2. (Summer): 9-63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/465144.

Descartes, René. 1641 Meditations. Translated by John Veitch, New York City, NY: Cosimo, Inc., 2008.

Ghosh, Amitav. 2017. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Guevara, Francisco. 2019. “Challenging the Sense of Time and Space: An Ethical Confrontation in Artist Residencies.” In Contemporary Artist Residencies: Reclaiming Time and Space. Edited by Taru Elfving, Irmeli Kokko, and Pascal Gieden, 133-149. Amsterdam: Antennae-Arts in Society Vaiz.

Guevara, Francisco. 2017. ‘In Mexico, Time Is Not Money’: A Residency Pushes Artists to Confront Difference and Colonialism.” Interview by Devon Van Houten Maldonado. Hyperallergic, May 18, 2017. https://hyperallergic.com/368070/in-mexico-time-is-not-money-a-residency-pushes-artists-to-confront-difference-and-colonialism/.

Haraway, Donna. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Heckscher, Christopher M. 2018. “A Nearctic-Neotropical Migratory Songbird’s Nesting Phenology and Clutch Size are Predictors of Accumulated Cyclone Energy.” Scientific Reports, 8, no. 9899, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-28302-3.

Hofmann, Gert, and Snježana Zorić, 2016. Presence of the Body Awareness in and beyond Experience. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Kafka, Franz. 1971. The Complete Stories of Franz Kafka. Edited by Willa Muir, Edwin Muir, Tania Stern, and James Stern. New York City, NY: Schocken Books.

Keightley, Emily, and Michael Pickering. 2014. Mnemonic Imagination: Remembering as Creative Practice. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions.

Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Kundera, Milan. 1980. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. Translated by Michael Henry Heim. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Latour, Bruno. 1996 “On actor-network theory: A few clarifications.” Soziale Welt 47, no. 4 369-381. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40878163.

Levi, Primo. 2000. The Voice of Memory. Translated by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Palazhy, Jayachandran. 2018. “Choreographing Somatic Memories and Spatial Residues.” In Bissell and Caruso Haviland 2018, 200-224.

Parkes, Graham. 2016. “Awe and Humility in the Face of Things: Somatic Practice in East-Asian Philosophies.” In Hofmann and Zorić 2016, 211-230.

Sacks, Oliver. 1996. The Island of the Colorblind. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Smith, Laurajane. 2015. "Theorizing Museum And Heritage Visiting." In The International Handbooks Of Museum Studies: Museum Theory. Edited by Andrea Witcomb and Kylie Message. 459-484. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Smith, L. and N. Akagawa. 2008. “Introduction.” In Intangible Heritage: Key Issues in Cultural Heritage. 1-9. London: Routledge.

Kiki Smith in “Stories,” 2003. Art in the Twenty-First Century, season 2. September 9, 2003, on Art21. https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s2/kiki-smith-in-stories-segment/.

Smith, Kiki. 1994. “Kiki Smith by Chuck Close.” Interview by Chuck Close. BOMB, Oct 1, 1994.

Steffler, John. 2017. “Wilderness on the Page.” The Goose 16, no. 1 (September): 1-15. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1346&context=thegoo…