ABSTRACT

Spaces contain and create meanings through the interplay of their surrounding physical and mental landscape i.e., geography, social activity, and representation. Like many defined spaces, Montréal is not only a social and spatial manifestation of a singular community, but an ideal conceived and constructed through interpretation, objectives, and media portrayal— a mosaic or assemblage. Conceptualising Montréal as a brand being one of the cultural capitals of Canada is deeply tied to an assemblage of its diverse roots and identity beyond its history. This thesis explores the notion of city branding to understand how a city’s image and reputation evolves in response to multiple forces of development, gentrification, transport, public spaces and arts, tourism, and financial pressures. In this study, I will be questioning how Montréal presents itself officially through the department of Tourisme Montréal to shape these narratives/identities.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Montréal Between Experience and Branding

1.2 City Branding

2. Montréal’s Brand Identity

2.1 An Analysis of Montréal’s Brand Images

3. Reimagining the City as a Creative Space

3.1 The Quartier International De Montréal (1997-2004)

4. Expanding Urban Mobility /Rescaling Infrastructure

4.1 Projet Bonaventure

5. Urban Renewal & Gentrification

5.1 Little Burgundy Renewal

6. Branding Montreal: An Ever-evolving Dialogue

7. Bibliography

Acknowledgements

The basis of this thesis stemmed from my interest in branding and curated aesthetics. The aim of this study is to contribute an interdisciplinary framework to analyze the curation of a branded space, using my hometown as a case study.

Over the past year, a number of people have been a source of support and inspiration. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my thesis advisor and program director, Ijlal Muzaffar, without his guidance and persistent help this thesis would not have been possible. Secondly, I would like to thank my family and friends for supporting me all this time. Thank you all for your unwavering support. Thank you Harry for editing my grad show page and relieving me of this headache. I cried 3 times so far today.

Upon completion of this thesis, I am now working as a conceptual artist and communications specialist for a project to revive and promote Montréal’s Chinatown, in collaboration with Ville de Montréal and Quartier des Spectacles.

Montréal Between Experience and Branding

Spaces contain and create meanings through the interplay of their surrounding physical and mental landscape i.e., geography, social activity, and representation. Like many defined spaces, Montréal is not only a social and spatial manifestation of a singular community, but an ideal conceived and constructed through interpretation, objectives, and media portrayal— a mosaic or assemblage. Conceptualising Montréal as a brand being one of the cultural capitals of Canada is deeply tied to an assemblage of its diverse roots and identity beyond its history. This thesis explores the notion of city branding to understand how a city’s image and reputation evolves in response to multiple forces of development, gentrification, transport, public spaces and arts, tourism, and financial pressures. Furthermore, I will be questioning how Montréal presents itself officially through the department of Tourisme Montréal to shape these narratives/identities. Therefore, I will focus on projects that draw out bottom-up urban community narratives to develop and expand on an urban brand — along with the consideration of action-based projects designed to care for urban sites and their social relationships. The authentic experience and representation provides a space of exploration into representational imagery and branding for a city. Place marketing can be explored by asking questions such as: Whom does it serve? How has this representation changed over time? How does imagery show tensions between contrasting representations? How do different actors represent the space? There have been studies on the interaction between place identity and image creation by researching how societal dynamics are played out in the urban environment.

Spaces contain and create meanings through the interplay of their surrounding physical and mental landscape i.e., geography, social activity, and representation. Like many defined spaces, Montréal is not only a social and spatial manifestation of a singular community, but an ideal conceived and constructed through interpretation, objectives, and media portrayal— a mosaic or assemblage. Conceptualising Montréal as a brand being one of the cultural capitals of Canada is deeply tied to an assemblage of its diverse roots and identity beyond its history. This thesis explores the notion of city branding to understand how a city’s image and reputation evolves in response to multiple forces of development, gentrification, transport, public spaces and arts, tourism, and financial pressures. Furthermore, I will be questioning how Montréal presents itself officially through the department of Tourisme Montréal to shape these narratives/identities. Therefore, I will focus on projects that draw out bottom-up urban community narratives to develop and expand on an urban brand — along with the consideration of action-based projects designed to care for urban sites and their social relationships. The authentic experience and representation provides a space of exploration into representational imagery and branding for a city. Place marketing can be explored by asking questions such as: Whom does it serve? How has this representation changed over time? How does imagery show tensions between contrasting representations? How do different actors represent the space? There have been studies on the interaction between place identity and image creation by researching how societal dynamics are played out in the urban environment.

According to social anthropologist Akbar Keshodar, major metropolitan areas all over the world compete against one another to deliver a distinguished brand through the arena of tourism, which is shaped through their conceived identity and the experience of those in the city (Keshodkar 98). The creation of a brand involves capturing and shaping the city as a product and known entity for local people, as well as visitors and tourists. While Keshodar wrote about the state-directed tourism branding and cultural production in Dubai, it is still applicable to other countries and cities that are concerned with their overall image like Montréal. In this arena, Montréal government holds a particularly complex dual identity, an english-speaking city situated in an francophone province within an anglophone North America. In reality, Montreal’s identity is always under contestation with its anglo-saxon and francophone roots as its local reality it is always fighting these tensions. The aim of this project is to interrogate the relationship between the local and the global in the city, through engaging participants in an accessible dialogue on government-initiated projects in relation to their personal environments. In this study, I employ an empirical and qualitative approach to examine and scrutinize the images used in the deliberate creation — or fabrication —of the city of Montréal. Thus, I explore the image of the brand of the city of Montréal, Québec as a product of imagery moulded by social and commercial processes, physical planning, and institutional intervention, instead of the mosaic or assemblage it is widely known to be.

The empirical research in the following sections is based on qualitative analyses and literature reviews. The qualitative information was used to evaluate perceptions of neighbourhood change and the effects on residents and community culture towards different branding initiatives. Information was obtained from scholarly critiques and official governmental documentation. The first chapter of this thesis explores the history of gentrification and urban renewal in Montreal, with a specific focus on a case study on Little Burgundy, a neighbourhood that once housed a large population of black railway workers in the 1880s. The deindustrialized neighbourhood has been the centre of Montréal’s Black anglophone population since the 1880s. By the 1970s, however, it became the site of urban renewal demolitions that made way for low-income public housing and an expressway, displacing many long-term residents and communities. The second chapter focuses on reimagining the city as a creative space, wherein public arts have been added to the agendas of city planners to engage public audiences. The Quartier International De Montréal used to be a vacant lot before it was restructured and built a new public square park, Place Jean-Paul Riopelle. With the addition of the fountain sculpture as a centerpiece, it created a space that honored design, architecture and culture activities in a renewed area of Downtown Montréal. The third chapter delves into the concepts of accessibility and mobility via transportation in a city, with a case study detailing the Bonaventure Project. Much of Montréal’s distinctive modernization of transit had been accelerated during the time Mayor Jean Drapeau served, as he prioritized metropolitan infrastructure for the mega-events of the 1970s. Transportation plays a huge role in navigating through an area, therefore highlighting a project that provides a user-friendly public space linking two neighborhoods contributes to how Montréal manages their image. Each of these chapters features a specific case study that impacts the image production of a city, based on research and other experiences.

City Branding

Government-devised place branding initiatives are underlined by an agenda to improve and promote places along with the town planners, local businesses, residents, and buildings associated with the place. In the case of Montréal, “branding” refers to the development of an image. Place branding is using branding strategies to promote a town, city, region or country, with the goal of attracting tourists, businesses, cultural events, and public and private investments (Hanna & Rowley 473). A focus on branding allows for an opportunity to understand how a place is perceived and experienced, as well as how those perceptions can be managed and improved. Virtually, local governments are able to have total control over how they represent their municipality on a maintained website (Grodach 184). The images, buildings, people, and places they choose to display and symbolize their city. Which images do governments draw on to construct a city identity? How do the projects they choose reflect the local population and built environment of the city? How do they decide on what or whom to show? How does the way local municipalities represent themselves affect how one experiences the city? While municipal authorities wish to highlight the curated images they promote, oftentimes marginalized/displaced communities and “flaws” are concealed. The imagery that is produced by local communities, the government, and corporate entities have been developed overtime, but they are also constantly changing. Marketing practices, such as slogans and tourist campaigns, have always been in place but even more so as countries become dependent on touristic ventures, thereby causing government entities and corporations to increasingly manage the image of the city and its urban identity.

The first element that needs to be addressed in unravelling the complexity of urban identity is the concept of the urban and the concept of the urban as a geographical place or space. A place or space plays an important role in establishing a sense of belonging and constructing identity.On the other hand, municipal governments are concerned with the need to market and differentiate themselves from other localities, especially in the age of globalization and increased transnationalism. These governments make a conscious attempt to shape and design a place branding and identity to promote to their target audiences e.g., tourists (Kavaratzis & Ashworth 506). An urban identity encompasses one’s social and self-identity and results from an individual’s everyday lived experiences within the context of the city. Although it is difficult to highlight every individual’s experiences, especially with concerns of intersectional experiences emerging from different classes, BIPOC, etc, I would like to dwell on the curated and managed identity fabricated by the government body and its associated officials. Places are linked with experiences, which are developed through its functional and tangible attributes, as well as the infrastructure and landscape strategies (Hanna & Rowley 473). A focus on branding allows for a development of how a place is perceived and experienced and how that is managed. A traveller’s choice depends largely on the images held pre- and post-visitation. Therefore, it is important to create a compelling brand experience outside the physical space. In other words, marketing is a planned practice of signification and representation. Kevin Lynch’s Image of the City highlights the importance of image development, which includes visual sensations of color, shape, motion, or polarization of light, as well as other senses (Lynch 3). Having a distinctive and legible environment, Lynch describes, heightens the depth and intensity of an experience (5). While Lynch’s work is more relevant in the 60s and 70s, where urban planning was predominantly informed by behavioural sciences, he outlines how having a distinctive environment heightens the depth and intensity of an experience (Lynch 5). Lynch delineates how people perceive, inhabit and move around in the urban landscape, which explains how an urban space is not just composed of its physical characteristics but equally by representations in mental images:

Environmental images are the result of a two-way process between the observer and his environment. The environment suggests distinctions and relations, and the observer—with great adaptability and in the light of his own purposes—selects, organizes, and endows with meaning what he sees. The image so developed now limits and emphasizes what is seen, while the image itself is being tested against the filtered perceptual input in a constant interacting process. Thus the image of a given reality may vary significantly between different observers. [...] An environmental image may be analyzed into three components: identity, structure, and meaning. It is useful to abstract these for analysis, if it is remembered that in reality they always appear together. A workable image requires first the identification of an object, which implies its distinction from other things, its recognition as a separable entity. This is called identity, not in the sense of equality with something else, but with the meaning of individuality or oneness. Second, the image must include the spatial or pattern relation of the object to the observer and to other objects. Finally, this object must have some meaning for the observer, whether practical or emotional. Meaning is also a relation, but quite a different one from spatial or pattern relation. (Lynch 7-8)

Lynch describes how image development is a two-way process between the observed and the observer and how the image can be strengthened by symbolic devices or by reshaping one’s surroundings (11). As mentioned in the quote above, there are three components of the image: identity, structure, and meaning. In this study, I take a material culture approach to look more closely at how the social imaginary of Montréal is being continuously formed by the identity of place. The use of images as material evidence serve to illustrate transformations in the urban imaginary of the city of Montréal.

On the other hand, while Lynch and many other authors emphasize the visual and physicality of spaces, Juhani Pallasmaa, a Finnish architect, engages with the phenomenological experience or involvement with all our senses of spaces. In his book The Eyes of the Skin (1996), explains how the sense of self, while strengthened by art and architecture, “allows us to engage fully in the mental dimensions of dream, imagination and desire” (Pallasmaa 11). To build on the importance of the environmental sensibilities, I wanted to bring in his work on how architecture should not be predominantly focused on sight. Pallasmaa embraces the multisensory apprehension of the urban environment and the city’s atmosphere:

The essential mental task of architecture is accommodation and integration. Architecture articulates the experiences of being-in-the-world and strengthens our sense of reality and self; it does not make us inhabit worlds of mere fabrication and fantasy. The sense of self, strengthened by art and architecture, allows us to engage fully in the mental dimensions of dream, imagination and desire. Buildings and cities provide the horizon for the understanding and confronting of the human existential condition. Instead of creating mere objects of visual seduction, architecture relates, mediates and projects meanings. The ultimate meaning of any building is beyond architecture; it directs our consciousness back to the world and towards our own sense of self and being (Pallasmaa 11).

Pallasmaa connects the atmosphere of an urban space as the overall feeling and tuning of the experience, opening up the trajectory of aesthetics beyond the field of architecture and peripheral visions. A place offers both functional (tangible) attributes and experiential (intangible) attributes, which additionally includes emotional experiences. Functional attributes are often reaped through infrastructure and landscapes, embracing the built environments, urban design and architecture, while experiential attributes could be realised through cultural events and entertainment (Hanna & Rowley 477). Pallasmaa additionally expands on how we have an innate capacity for remembering and imaging places:

Perception, memory, and imagination are in constant interaction; the domain of presence fuses into images of memory and fantasy. We keep constructing an immense city of evocatino and remembrance, and all the cities we have visited are precincts in this metropolis of the mind [...] There are cities that remain mere distant visual images when remembered, and cities that are remembered in all their vivacity. The memory re-evokes the delightful city with all its sounds and smells and variations of light and shade (67-70)

This passage highlights the importance of post-visitation images of a particular area and how image making labor does not only happen when one is in the environment but a continuous effort that involves pre-expectations and how they dwell in our memories. Following Yuriko Saito’s Aesthetics of the Everyday as a framework for the urban environment, we come to understand our everyday environment as a site for visual exploration and appreciation. While Western aesthetics tend to natural objects and built structures as fine arts, Saito challenges this limited scope by widening the trajectory to include objects, events, and activities that constitute people’s daily life (Saito 2019). In this study, the “everyday” of everyday aesthetics will be coined with one’s environment and in this case, the urban environment of Montréal. Contemporary aesthetics is moving away from an optically centric standpoint, I want to incorporate one’s phenomenological experiences towards aesthetics in relation to the building of an urban identity. That is not to say that the spectacle of a city has no place, but this research will focus on overall embodied experiences. By blurring the creator/spectator dichotomy, Saito explains how artists create art as a joint venture in collaboration with the general public to create:

Art and aesthetic in this context are not regarded as decorative amenities or prettifying touches. Rather, organizational aesthetics and artification strategy are based upon the premise that humans negotiate life, whatever the context may be, through sensory knowledge and affective experiences by interacting with others and the environments. As such, workinging with the aesthetic dimensions of these professional activities and environments cannot but help achieve the respective goals and, perhaps more importantly, contribute to the wellbeing of the members and participants. Art and aesthetics can be a powerful ally in directing human endeavors and actions and determining the quality of activities and environments (Saito 2019).

Saito reinforces Pallasmaa’s atmospheric appreciation of aesthetics, rather than placing great weight onto physical realities. Although Saito holds true in the context of 20th century Japan, where an everyday can correspond to a largely middle class and uniracial society, I am placing the importance of the atmosphere on the foreground with her works. Each of the authors mentioned (Lynch, Pallasmaa, Saito) all help in setting up the situation of a cityscape and establish the importance of image creation as well as the embodied experience that contributes to the image. Throughout this paper, I will be expanding on the conceptualization and theories of city branding onto the urban environment of Montréal.

Montreal's Brand Identity

The famous Lewis Mumford, urban historian and sociologist, question from the 1930s, “What is a City,?” has evolved into a much more complex question. It is no longer a “theatre of social action,” wherein Mumford described the city as a constructed, physical space but now we envision society and the city is much more than its concrete manifestations. The island of Montréal is situated between the Saint Lawrence river and the Rivière des Prairies in the province of Quebec, making Montréal the perfect port city and it is still considered as one of the country’s major industrial centers. The city was named after Mont Royal in the 18th Century, which is its most prominent geographic feature. The economy was mainly based on the fur trade for the first 150 years before evolving into a more diversified commercial metropolis. In more recent years, Montréal is considered the economic center of Quebec, as well as the second financial center of Canada. Montréal is Canada’s second most populous city, also known for being one of the bilingual capitals in the country. French is the official language, but the city has a very diverse demographic beyond its French speaking population. Being colonized first by the French and then the British in 1760, Montréal is a melting pot of two European countries and deeply influenced Montréal’s architecture and urban planning. The city of Montréal is divided into 19 boroughs with a population of more than 4 million inhabitants (Statistics Canada, 2016). Montréal is home to six universities and is considered one of the best student-friendly cities in the world. The city stands out for its design leadership, and was awarded by the UNESCO Ville de Design in 2006. The city continuously seeks to differentiate itself with support from its peculiar historical and linguistic features and it endeavours to sustain its title as a cultural capital of Canada.

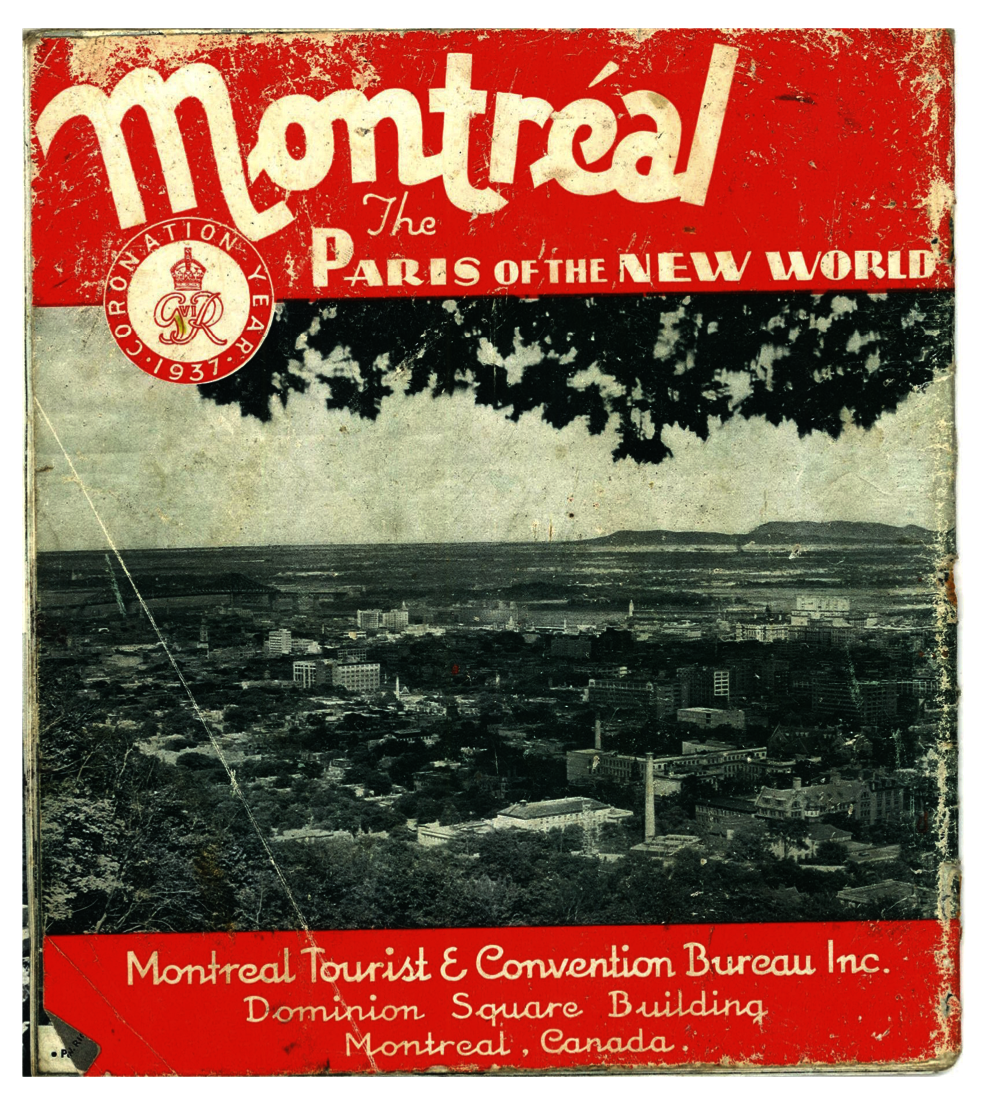

Much of Montréal’s advertising and official branding identity is done through Tourisme Montréal, the municipal department of tourism of the city. The department was first founded in 1919 by the Automobile Club of Montréal and several other companies as a collaboration to promote Montréal and its road network in order to develop some touristic activities (“History of Tourisme Montréal”). By 1924, the bureau was renamed the Montréal Tourist and Convention Bureau as an attempt to attract business travel into the city. Slogans such as “Cosmopolitan Montréal” and “Abroad Without Crossing the Sea” were used to render the image to encourage business travel to the city. By the 20th Century, Montréal became the center for commerce and finance in Canada and North America’s second-largest port city (“History of Tourisme Montréal”). Combining North American comfort and European charm, Montréal has capitalized on the reputation of being the “Paris of the North”. Montréal’s transformation into a modern metropolis in the 1960s is characterized with projects such as the construction of Place des Arts and Places Jacques-Cartier. In more recent times, with social media on the rise, Tourisme Montréal adopted campaigns such as the #MTLMoments.

In March of 2015, Tourisme Montréal announced its new branding image to present Montréal’s identity as a “creative, energetic, and dynamic city that’s always on the cutting-edge of new discoveries and experiences” (“Tourisme Montréal puts the city at the heart of its new brand image”). What does it mean to be “creative, energetic, and dynamic? What are the meanings behind these languages? Politicians can attach meanings to the concepts which best suit their interest or the actual situation, but there is much ambiguity that surrounds the adjectives chosen for the new branding. Image and reputation have become essential parts of the state's strategic equity; similar to commercial brands, image and reputation are built on factors such as trust and customer satisfaction. Montréal, as well as many other cities, definitely battles with the need to be modern and current while preserving their rich histories. We can observe the “creative, energetic, and dynamic” city brand through the three case studies throughout the rest of the chapters of this thesis. Although my focus on the commercialised and government-initiated representation of the city, may not include all representational practices in everyday life in Montréal, they are still influences that affect the identity of the space, individuals and the community.

An Analysis of Montréal’s Brand Images

Tourisme Montréal's Current Logo, 2015

Image

Image

Image

Articulating a brand focuses on the processes associated with the brand, which includes verbal or visual identities through choices of its name, logo, colour palettes, and images (Hanna & Rowley 469). In this section, I will be reviewing some of the branding images of Tourisme Montréal over the years and how it correlates with the city’s realities. Tourisme Montréal’s new and current brand image and its iterations (See Figures 1 & 2) was imagined under the creative direction of Claude Auchu of Lg2boutique and was revealed in 2015, as mentioned previously. It is adaptive and varies with the seasons and the events that mark the city, attempting to create a well-rounded experience (“Tourisme Montréal puts the city at the heart of its new brand image”). Additionally, it adds significant emphasis on the accent on the é, representing the North American French flare of the city. It gives tribute to the past while rendering a more modern and minimalistic look to the brand image. The city often gives tribute to the good ol’ days, even its slogan since the mid 20th century “Je me souviens” translates to “I remember” (“La devise québécoise «Je me souviens»”). Taking all these official promotional elements into account, does it represent the true nature of Montréa’s brand image? Governments often attempt to only highlight the positive aspects of the city, while concealing its shortcomings.

The é can be seen in each iteration (figure 2), respectively corresponding to a different event, for example the summer fireworks festival in the bottom middle. It seems a bit over simplified but it follows along mainstream minimalistic design trends, many of which often opens more space for diverse interpretations to its audience. It is not the first time Montréal has stressed its Francophone identity into its branding, rather the french connection stays consistent even from the 1930s when Tourisme Montréal, otherwise known as the Montréal Tourist & Convention Bureau at that time, marketed the city as “The Paris of the New World” and created a booklet that was sent to their bordering American neighbors.

However, the city’s slack laws and reputation regarding the consumption of alcoholic beverages and brothels in the 1920s is what truly earned its title of “The Paris of North America” (“Remembering Montréal Cabarets”). This reputation and the province’s minimal legal drinking age of 18 makes it a hot spot for tourists from higher drinking minimums, especially the United States. Comparing the city to a bigger city like Paris, diminishes Montréal’s individual identity and solely features the Francophone side.

Image

Figure 4

Image

The next two posters (figures 4 and 5) are by artist Roger Couillard, a visual artist and poster designer, known for his bright primary colors, lineless shapes, and minimalist compositions. He created posters for a variety of national institutions such as the Canadian Pacific and Canadian Steamship Lines. Many of his posters of the city serve as art historical evidence of Montréal’s self-presentation to the outside world. As an attempt to get tourists to visit during the winter, the city was marketed and praised for its supposed perfect winter wonderland weather (“Remembering Montréal Cabarets”). While skiing on Mont Royal is possible, this specific publication from the 1950s gives off a false illusion that there is a mountainous playground in the center of the city ideal for winter activities while in reality only a bit of cross-country skiing is possible and certainly not suitable for alpine enthusiasts. To be fair, Montréal does receive a large amount of snow during the winter season but the city’s conditions and natural circumstances do not allow for sports that call for mountainous slopes.

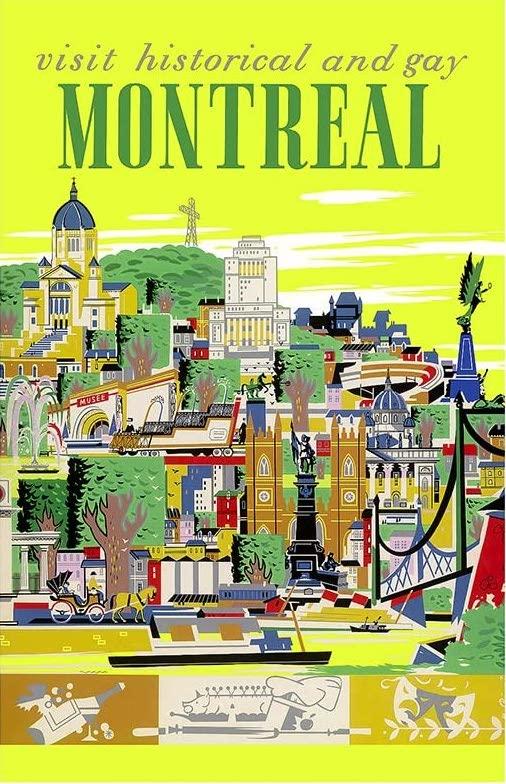

This second selection of a poster by Roger Couillard, highlights the bustling modes of transportation offered within the city, as evidenced by the steam boats, rowboats, horses and buggies, bridges, trams, and more. The image presented depicts Montréal much more bustling and condensed than it actually was. The city’s major cultural sites, such as the Saint Joseph’s Oratory and the Notre-Dame Basilica, are prominently displayed and adjacent to one another but in reality these attractions are on opposite ends of the island. In addition, during the late 1990s, Montréal recognized the potential of the Gay Village as a tourist destination and therefore spent a great deal of efforts to produce maps, magazines, brochures, etc to promote the Village, such as a series of “Visit Historic and Gay Montréal” posters. Official government produced material presents the Village as a spectacle, a place of fantasy and suggests that Montréal as a place to discover sex and entertainment, connecting into the red-light fantasy that was attached with the “Paris of the North” imagery.

Figure 5

Image

These are just a few of the images of Montréal by governmental institutions that are put out as representations of the city to the rest of the world. Even so, we can see different phases of branding it has been through. Montréal has gone through many waves of branding, one of the most notable one being Major Jean Drapeau’s vision of presenting the city as an international hub during the era of the World Expo and the Olympics. With the desire to represent Montréal as a modern, world-class Francophone city of the future, Drapeau had visions of “grandeur” and growth that led to increased funding for city development (Levine 105). The World Expo of 1967, along with massive public works expenditures, physically reshaped Montréal. This included major highway expansions and bridges throughout the Montréal region, the construction of the public subway system, and the underground network of pedestrian walkways, otherwise known as the ville souterraine. These grand events were used as catalysts for major investments in international hotels and shopping, in addition to state-of-the-art public infrastructures, which would later become government-owned infrastructures. Drapeau’s aspiration to make Montréal a global destination for tourists and investors was conceptualized alongside global mega-events like Expo ‘67 and the Olympic games. He aimed to use the exposure the city would receive from hosting such events to demonstrate to the world the emergence of Montréal as an economically booming and culturally vibrant city, as well as entice an influx of tourism. Expo ‘67 was a success, with over 50 million visitors, surpassing the estimated 35 million, appreciating the city’s mix of modern and historic architecture (Whitson 1219). The general exposition was held on two artificial islands, Ȋle Sainte-Hélène and Ȋle Notre Dame, which were both partially made out of the excavation debris from the Metro system construction project. The exhibition was part of an urban redesign project and pushed the expectations of Montréal, articulating the city’s ambition to extend and expand into new spaces and into the future. As a result, Montréal’s skyline was elevated with new, imposing buildings, sealing the past and manifesting Drapeau’s imaginary globalized Montréal.

Following Montréal’s Mega-Events Era, was the Tourism Infrastructures of the 1980s-2000s. Shifting away from mega-events of the last two decades, Montréal moved on to becoming heavily committed to drawing in tourism for economic development. Since the 2000s, there has been an emphasis on design as an agent of urban economic development. The city of Montréal, has been in collaboration with a number of partners, some of which include Culture Montréal, the Ministere des Affaires Municipales, and others, to mobilize a broader creative city script for initiating dynamic design in the city (Rantisi & Leslie 365). With these efforts, Montréal became the first North American city to be designated as a UNESCO Ville de Design in 2006 (“Launch of Montréal, UNESCO City of Design Initiative”). The emergence of Montréal as a center of design is due to its rich institutional nexus that supports culture in the city and in the broader province of Quebec, creating a strong cultural mandate with tension arising due to being a Francophone metropole in an Anglophone North America (Rantisi & Leslie 311).

Physical realities of a place are often differing and instantiations, whereas the experience is the actual product. Landscapes change due to changing desires, technologies, and economies. Places cannot keep the same conditions forever, therefore leaders should be able to consider the forms of spatial planning that enforces change while being able to retain some older qualities. Leaders should be able to re-energise and regenerate existing landscapes with the development of arts and cultural quarters. Cultural quarters can lead regeneration and stimulate innovation and creativity. Although one must be cautious of gentrification and losing the distinctiveness of the space (Hanna & Rowley 477). The biggest challenge many urban planners face is how to promote the historical uniqueness of the city while presenting themselves as modern and contemporary. Shaping the image of a brand requires maintaining a level of consistency and we can definitely see that with Montréal’s francophone pride and advocacy that is streamlined to many of the city’s marketing strategies.

As mentioned in Grobach’s Urban Branding, there is also a tendency to misrepresent the city and exclude its disadvantaged residents in order to promote it in a positive way (183). Given so, it is still important to consider and understand the image strategies the municipal government employs because they play an important role in shaping our perception and influence how we think about the city (Grodach 182). The way the city is marketed shows how it can draw our attention toward how the city is depicted and thereby for whom the city is imaged. Although many of the government initiated urban renewal projects I will be introducing later on have specifically catered to more privileged sections The image of Montréal and efforts to control its urban development are moulded by the interests of local economic development and managed by governmental powers and corporations. Branding efforts prioritizes profits over other forms of local community development, the image being presented is granted power to be seen as authentic and true. This act of representation implies that reality can be interpreted by those who manage it, which oftentimes has inconsistencies in the individual perception and are deliberately distorted to elicit emotion or attraction for a broader population. The marketing of a place is part of the commodification of everyday life, urban culture and imagery are manipulated and represented by institutional codies to create new, alluring images of the place. Greenberg’s Branding Cities, expresses how ““authentic” urban lifestyles, public spaces, and local traditions are used as vehicles for corporate branding” (Greenberg 2000: 255). In the following chapters I will be presenting three government initiated urban renewal projects and the implications on Montréal’s urban identity and urban branding.

Branding Montreal: An Ever-evolving Dialogue;

Through my analysis of the constructed branding of Montreal, I have shown the city spaces that are formed in part through place marketing and institutional alliances. Future research will further the application of empirical methodologies in this field and continue dissecting the intricate construction of spatial imagery by employing a material cultural approach to the urban fabric. Additionally, more research is needed that explores the connections between place marketing, place meaning, and community self-perception. Due to the complexity of defining imagery, it is unclear where the authentic Montreal culture and constructed image begin and overlap. The degree to which commodified image is subsumed in a dynamic community identity is also difficult to extract from the imagery overall. The informal and formal uses of spaces of community building often happens outside of branding, and sometimes the act of branding ironically brings that informalness out through local bottom-up initiatives. In the past, branding has been used to present a homogenized image through big-scale projects initiated by governmental authorities; however, there is a possibility towards a movement that is smaller scale and sustainable in hosting more informal activities. Does branding only mean to unify things? Is this a tension cities will always have to harness? How do we keep the different imaginations in dialogue and give room to artists working in these spaces? Municipal authorities are oftentimes focused predominantly on the brand experience they wish to present and deliver to visitors rather than the authentic brand that the city’s residents communicate. The emphasis is on the experiential memories, not just the built environment. While Lynch and Pallaasma do not deal with the issues of lost histories, we can use their theories and proposals to argue that there are traces of meaning left even as places are changing and there is always a possibility of returning to those meanings. As Lynch states in chapter 3, “there are other influences on imageability,” giving note to the importance of emotional connections that may serve more than the physical features of a space. Additionally, there can be further research into the general nature of city branding and the strategies adopted by practitioners to evaluate and enhance place experiences. While environments are constantly changing and transformations are inevitable, it is also important to memorialize the histories of places. There are possibilities to do so within branding and public spaces, using the same instruments of city planning as were utilized with Montreal. Going forward, how can we best do this and why is it important?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abramson, Daniel M. Obsolescence: an Architectural History. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Boarnet, Marlon G. “The Transportation Transformation of Our Cities Will Be More Important

Than Density Changes.” Cityscape, vol. 15, no. 3, 2013, pp. 175–178. JSTOR

Communaute metropolitaine de Montréal, 2012. Observatoire Grand Montréal http://observatoire.cmm.qc.ca/swf/ indicateurs Metropolitains.php.

Creativity, and Gentrification down the Urban Hierarchy.” Southeastern Geographer, vol. 56, no. 4, 2016, pp. 384–408. JSTOR

Deschênes, Gaston. “La Devise Québécoise ‘Je Me Souviens.’” Encyclopédie Du Patrimoine

Culturel De L'Amérique Française , Gouvernement Du Canada, 15 Dec. 2009

Douglas, Walter S. “Urban Transportation and Metropolitan Development.” The Military

Engineer, vol. 53, no. 355, 1961, pp. 365–367. JSTOR

El-Geneidy, Ahmed, et al. “Evaluating the Impacts of Transportation Plans Using Accessibility

Measures.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research, vol. 20, no. 1, 2011, pp. 81–104.

Filion, Pierre. “Comment: Is There Such a Thing as Montréalology?” Anthropologica, vol. 55, no. 1, 2013, pp. 87–92. JSTOR

Goyette, Kiley. “Urban Governance After Urban Renewal: The Legacies of Renewal and the

Logics of NEighbourhood ACtion in Post-Renewal Little Burgundy (1979-1995).” Master’s Thesis, Concordia University, 2017.

Grierson, Elizabeth. Transformations: Art and the City. Intellect, 2017.

Greenberg, Miriam. “Branding Cities: A Social History of the Urban Lifestyle Magazine.” Urban

Affairs Review, vol. 36, no. 2, Nov. 2000, pp. 228–263, doi:10.1177/10780870022184840.

Grodach, Carl. “Urban Branding: An Analysis of City Homepage Imagery.” Journal of

Architectural and Planning Research, vol. 26, no. 3, 2009, pp. 181–197. JSTOR

Hanna, Sonya, and Jennifer Rowley. “Place Brand Practitioners' Perspectives on the

Management and Evaluation of the Brand Experience.” The Town Planning Review, vol.

84, no. 4, 2013, pp. 473–493., www.jstor.org/stable/23474360. Accessed 28 Nov. 2021.

High, Steven. “Little Burgundy: The Interwoven Histories of Race, Residence, and Work in

Twentieth-Century Montréal.” Articles Urban History Review, vol. 46, no. 1, 2019, pp.

23–44., doi:10.7202/1059112ar.

“History of Tourisme Montréal.” Tourisme Montréal, Tourisme Montréal, 25 Sept. 2019,

apropos.mtl.org/en/organization/history-tourisme-montreal. Accessed 16 Nov. 2020.

Hulbert, Tammy Wong. “The City as a Curated Space: a Study of the Public Urban Visual Arts in

Central Sydney and Central Melbourne, Australia.” Master’s Thesis, RMIT University, 2011.

Jean, Sandrine. “Neighbourhood Attachment Revisited: Middle-Class Families in the Montreal

Metropolitan Region.” Urban Studies, vol. 53, no. 12, 2016, pp. 2567–2583. JSTOR, doi:10.1177/0042098015594089

Kavaratzis, Mihalis, and G. J. Ashworth. “City Branding: An Effective Assertion Of Identity Or

A Transitory Marketing Trick?” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, vol.

96, no. 5, 2005, pp. 506–514., doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2005.00482.x.

Keshodkar, Akbar. “State-Directed Tourism Branding And Cultural Production In Dubai, UAE.”

Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development,

vol. 45, no. 1/2, 2016, pp. 93–151. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26384881. Accessed 28

Dec. 2020.

“La Joute.” Art Public Montréal, artpublicmontreal.ca/en/oeuvre/la-joute/.

“Launch of Montréal, UNESCO City of Design Initiative.” Chaire UNESCO En Paysage Et

Environnement De L'Université De Montréal, Université De Montréal, www.unesco-paysage.umontreal.ca/en/researches-and-projects/montral-ville-unesco-de-design. Accessed 12 Dec. 2020.

Levine, Marc V. “Tourism-Based Redevelopment and the Fiscal Crisis of the City: the Case of

Montréal.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research, vol. 12, no. 1, 2003, pp. 102–123.

JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44320751. Accessed 28 Nov. 2020.

Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1960. Print.

Manaugh, Kevin & El-Geneidy, Ahmed. (2012). Who Benefits from New Transportation Infrastructure? Using Accessibility Measures to Evaluate Social Equity in Transit Provision. Accessibility Analysis and Transport Planning: Challenges for Europe and North America. doi: 10.4337/9781781000106.00021.

Markley, Scott and Madhuri Sharma. “Keeping Knoxville Scruffy?: Urban Entrepreneurialism,

Creativity, and Gentrification down the Urban Hierarchy.” Southeastern Geographer, vol.

56, no. 4, 2016, pp. 384–408. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26233815. Accessed 28 Nov.

2021.

Mayrand-Fiset, Mireille. “Remembering Montreal's Cabarets.” Active History, University of Saskatchewan, 5 Dec. 2012.

Miciukiewicz, Konrad, and Geoff Vigar. “Mobility and Social Cohesion in the Splintered City:

Challenging Technocentric Transport Research and Policy-Making Practices.” Urban

Studies, vol. 49, no. 9, 2012, pp. 1941–1957. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26150970.

Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

Montréal, Tourisme. “Tourisme Montréal Puts the City at the Heart of Its New Brand Image.”

Cision Canada, 24 Dec. 2018

“Programmes Particuliers D'urbanisme.” Ville De Montréal, ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=7317%2C79383650&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL. Accessed 16 Nov. 2020.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Eyes of the Skin. Wiley-Academy, 2005. Print

“Projet Bonaventure.” Projet Bonaventure, projetbonaventure.ca/.

Racine, F. (2016). The Evolution of Urban Design Practice in Montreal from 1966 to 2004.

Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 41(1), 19–30.

Rantisi, Norma M., and Deborah Leslie. “Branding the Design Metropole: The Case of Montréal,

Canada.” Area, vol. 38, no. 4, 2006, pp. 364–376. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20004561. Accessed 16 Nov. 2020

Saito, Yuriko, "Aesthetics of the Everyday", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2019. Print.

Twigge-Molecey, Amy. “Exploring Resident Experiences of Indirect Displacement in a

Neighbourhood Undergoing Gentrification: The Case of Saint-Henri in Montréal.”

Canadian Journal of Urban Research, vol. 23, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1–22. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/26195250. Accessed 16 Nov. 2020.

Whitson, David. “Bringing the World to Canada: 'The Periphery of the Centre'.” Third World

Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 7, 2004, pp. 1215–1232. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3993806.