ABSTRACT

All Bodies Wander explores how aspects of the environment can evoke the presence of a living organism. Based on research within the natural world, this body of work includes documentation of sites, processes, installations, and artifacts made primarily with handmade paper.

This practice forms a threshold between two worlds, two bodies, two different understandings—it creates sites for connections with something, someone, or a place that cannot be directly accessed.

Image

I am preoccupied by how environments behave. In paying attention to the periphery of our daily experience, I believe that we can recognize the earth itself as a living organism—impressionable, ever-changing, and constantly in motion. The earth is a sensing body that is much like our own. Nature displays overt shifts such as sunlight, weather and seasonality; it also reveals embedded, often nebulous processes that account for multiple scales and deep time. By engaging with these systems, I directly connect with a site’s history, ecology, and the other liminal aspects that may otherwise go unnoticed.

Rather than depict my findings precisely, I invent an experience that is suggestive of them—a reconfiguration of nature. In the process of creating an installation, I construct spaces that negotiate what is real or imagined, logical or emotional—spaces where the natural world is embodied as something rhythmic, alive, and breathing. These installations are meant to be rearranged, suggesting the possibility of a multiplicity of presences. Although they are about a specific environment and place, they are not absolutely site-specific in themselves. They can be set up in different places, they are transportable and adaptable and meet viewers where they are.

Image

All Bodies Wander (Breath)

handmade kozo paper, walnut hull dye, iron oxide, methyl cellulose, sheet plastic, inline fan

7' x 5' x 5'

2021

Forming a boulder out of handmade paper, I translated its expected, heavy, seemingly permanent, and inert existence into something more transient and ephemeral, like myself. It may seem counterintuitive to use such a fragile material to represent rock, however, the malleability of paper allowed me to make direct impressions that trace my time spent in the Lincoln Woods. That voluminous imprint of overlapping paper sheets transported from the site becomes fairly amorphous, perhaps even bodily, suggesting a lifeforce. By inflating the form, I give the boulder breath, allowing it to inhale and exhale recognizably. The boulder connects the viewer to its own lived experience, to a geological epoch we cannot quite fathom—it gives the landscape a consciousness.

Image

Image

Image

Image

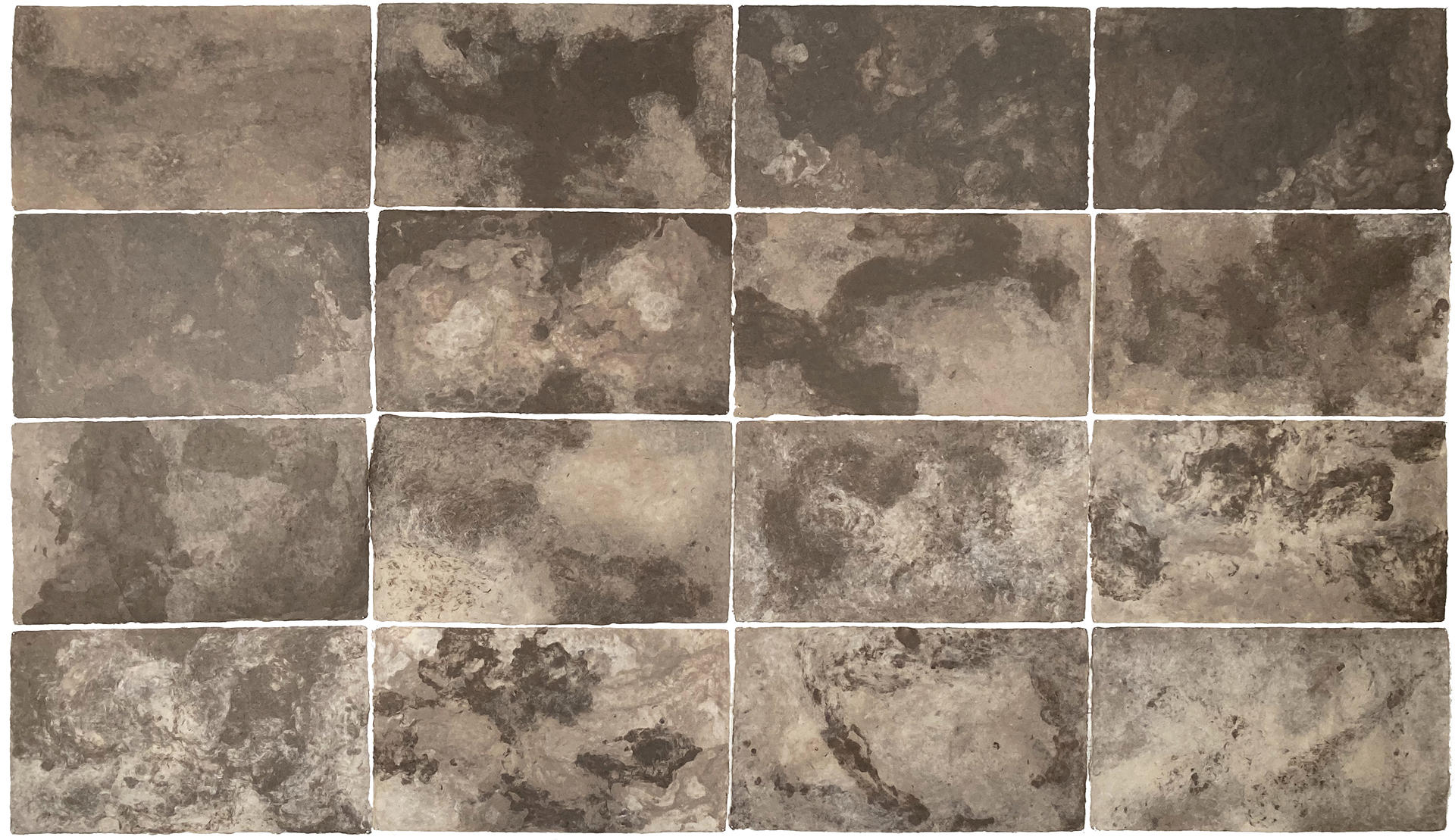

Untitled (Modules 7-11, 13, 14-17, 32-34, 45, 51)

handmade kozo paper, walnut hull dye, iron oxide

176" x 100" grid

2021

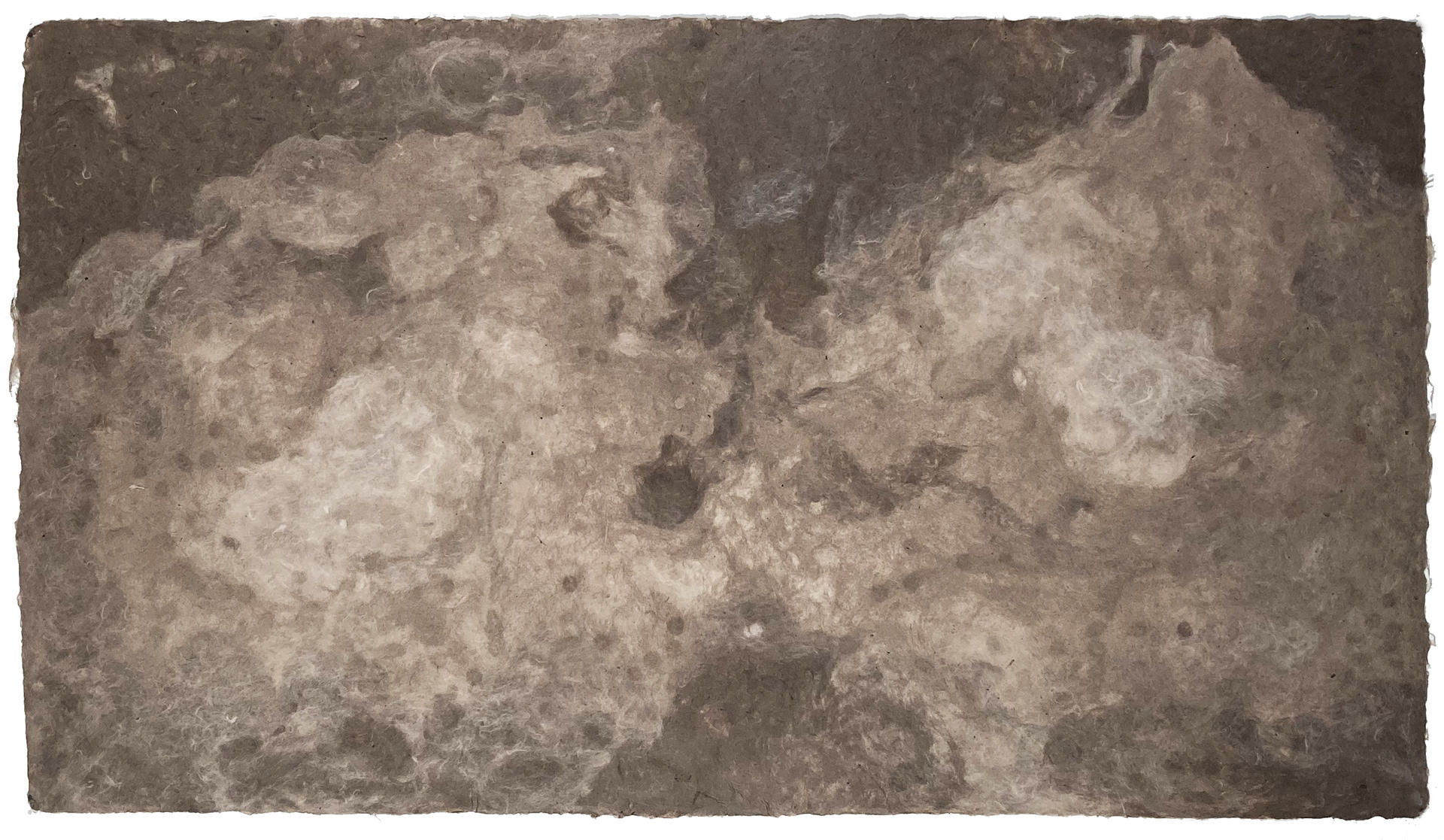

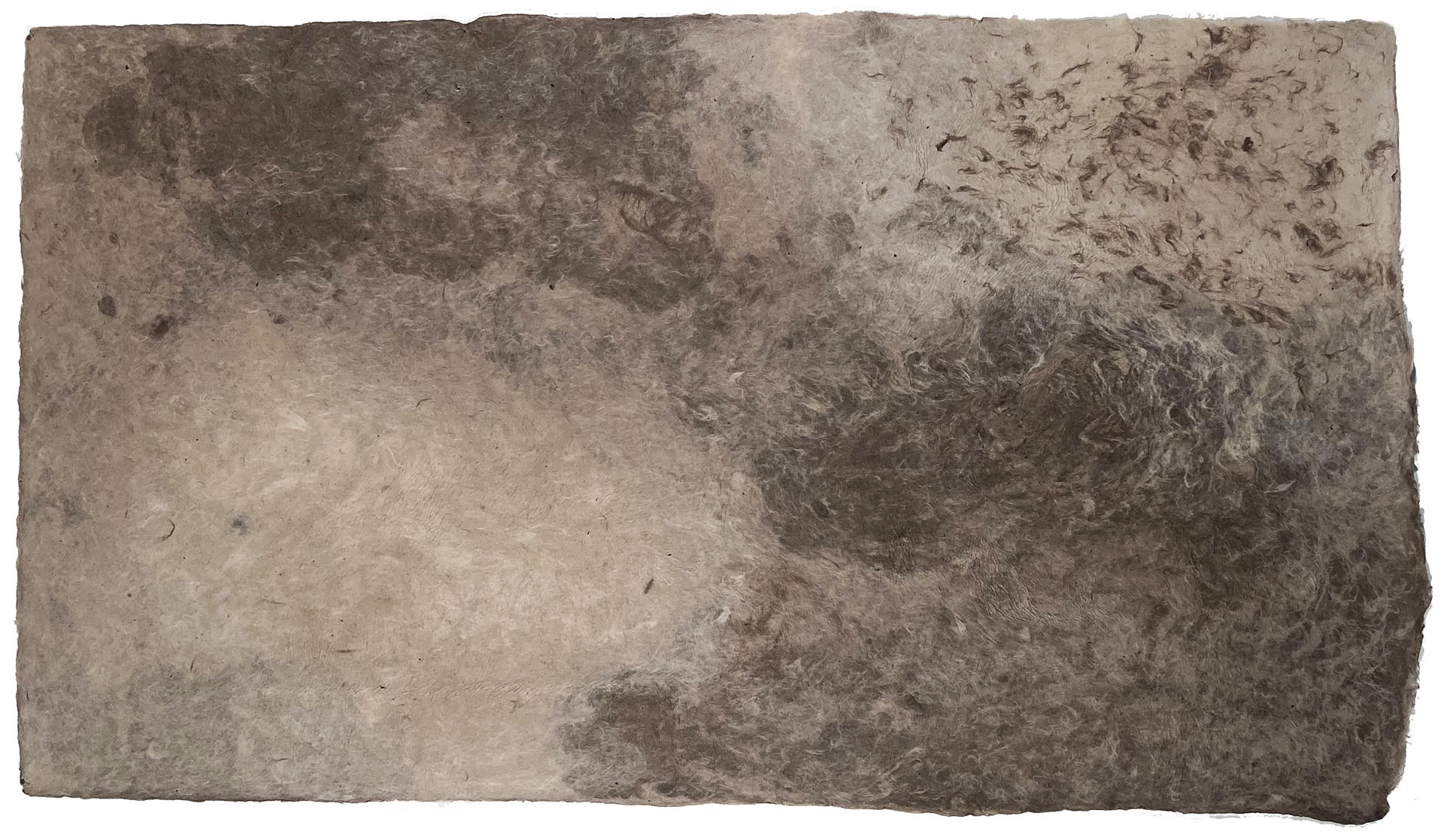

Pouring pulp to form large sheets of paper is a slow, methodical, and labor-intensive procedure. It requires time, patience, and plenty of water. As pulp and water spill through my fingers, they leave gentle contours. These reveal the reciprocal process of my movements and the material’s responses as I swirled the pour bowl over the porous surface of each formed sheet. These marks build up topographies that are suggestive of many scales. The gestures became equally reminiscent of the terrain of the greater site, of the pits and scars on the boulder’s weathered surface, as well as the suggestion of the rudimentary life forms like lichen species that are often found occupying its crust.

Even the process by which I change the paper, through dying and sun-bleaching the fiber, mimics the natural effects of time on objects. Over millennia, these weathered boulders often leach earth-tone minerals, erode under acid rain, crack during freeze-thaw events, and fade under prolonged sun exposure.

Image

Untitled (Module 13)

handmade kozo paper, walnut hull dye, iron oxide

25" x 44"

2021

Image

Untitled (Module 32)

handmade kozo paper, walnut hull dye, iron oxide

25" x 44"

2021

How did a ten-ton boulder end up leaning upright against another? Over the span of more than a millennium, these rock formations moved several hundred miles across the earth from their place of origin. Gouges in the bedrock, called chatter marks, show evidence of the boulders' movement by glaciers across the landscape. Melting glacial ice transported the boulders so that they ended up balancing on one another. Such erratic forms are often oddly positioned and do not fit in with their surroundings. Thinking about these huge boulders compels the mind to imagine enormous shifts in scale, time, and place. The enormity of these parameters is difficult to imagine relative to the human body and lifespan, engaging the sublime sense of smallness that we feel in front of nature.

Image

Remnant (Erratic Chatterings)

pigmented cotton fiber, walnut hull dye, iron oxide, methyl cellulose

26" x 58"

2021

Image

Image

I think about these massive boulders as conscious beings who experience the world differently from humans. I sit near them, climb on them, and breathe next to them. I wonder if they breathe too, only that it is beyond my ability to perceive it. I am attempting to find a tactile, direct relationship between myself and these strange entities. However, you do not have to dwell on giant boulders to consider the enormity of time in terms of the history of the earth. A pebble contains it as well—the potential for all things to be alive, have histories, and convey millions of years in their essence.

These glacial erratics have brought me back down to earth; they have instilled a deeper appreciation of what might otherwise be invisible presences. Awareness of the environment and empathy towards other humans can reside in the breath, even in the heartbeat.

Image

Image

Image

Image