Image

ABSTRACT

The escalating climate crisis has exposed many cracks in conventional building systems. Modern architectural processes contribute to climate change by consuming high levels of energy throughout the building cycle—from sourcing materials to construction to energy use once buildings are in use. Conventional architecture’s emphasis on heaviness and permanence makes these problems unavoidable. Light, temporary architecture is a solution to both the environmental impacts of the practice (the cause) and to the challenges of living in ever more impermanent situations (the effect). As climate change continues to manifest in rising global temperatures, sea level rise, drought, unpredictable weather, and natural disasters, the need for new solutions will continue to grow.

Textile Architecture is a process-led and systems-based design solution for creating transitional architectural spaces from woven jacquard textiles. Jacquard fabrics are especially suited to temporary architecture because complex patterns and structures can be combined seamlessly across a surface of continuous material, and the weaving process can engineer performance into the fabric at strategic locations through weave structure and fiber content. The result is a light, flexible textile that can be adapted depending on the local needs of the user, whether they are children in public greenspaces or people facing displacement. Textile Architecture is not new, but it is ready for reinvention and activation by textile designers working in collaboration with architects. It stands as a blueprint and points toward a lighter, more sustainable future for architecture and the earth.

Image

Image

UNFOLDING TEXTILE ARCHITECTURE:

PROCESS & PROTOTYPE

Textile Architecture is both a designed structure (a product) and a design research method or system (a process) that explores the potential for textiles to be used in creating infinite variations of free-standing architectural structures. The intent behind this research was not to provide immediate solutions to building scale pavilions or temporary structures. Rather it is the beginning of an exploration into what is possible, and the prototype is a proof of concept.

If textiles are used to solve other design challenges, why not apply them to architecture too? Textile-based architecture is perfectly suited to occupy the space between permanent architecture (houses, apartment buildings, institutions, skyscrapers, etc.) and temporary spaces (tents, pavilions, shade structures). Textile architecture can be useful in seasonal industries, temporary spaces (pop-ups, festivals), disaster relief, in places where permanent architecture can harm the natural environment, or places affected by climate change. I am not suggesting that we should replace all permanent structures with textile architecture but rather allow textiles to be another system of building available to define space. Textile architecture can fill the gaps that traditional architecture created by providing solutions to the in-between spaces; semi-permanent spaces, inside/outside, semi-private/semi-public. But much more importantly, it is lightweight, and therefore provides a solution to one of the most pressing environmental problems of our time.

Over the past year, I have gained the skills—specifically working with the jacquard loom— necessary to execute a project I have long imagined. I have pushed my understanding of how weave structure, fiber content, and weaving and finishing processes could be engineered to create an architectural structure made of continuous textile material. While I knew that weaving as a design process had qualities advantageous to architecture, i.e. it can create a continuous surface in both the warp and weft direction, allowing for material strength and performance; in addition to skills, I also needed a set of criteria, restrictions, and parameters in which to make decisions.

Early in the design process, I established four guiding principles for the structure:

- it must be as self-supporting as possible

- it must be easy to transport

- the jacquard textile could not be cut into

- finishing processes would be minimal

My process was guided by the verbs illustrated below. Fold, Translate, Weave, Finish, Model, Install.

My research based process exposed me to architects and designers who have been working at the intersection of textiles and architecture with goals similar to my own. The advantage of textile driven architecture would be that architectural elements could be incorporated into the textile directly off the loom.

It would reverse the relationship between textiles and architecture from textiles selected to meet architectural purposes to textiles designed to be architectural elements.

My research led me to question what would have happened had textile designers been collaborators from the inception of the project. Further, what if a textile designer had actually taken a lead role in designing lightweight architecture?

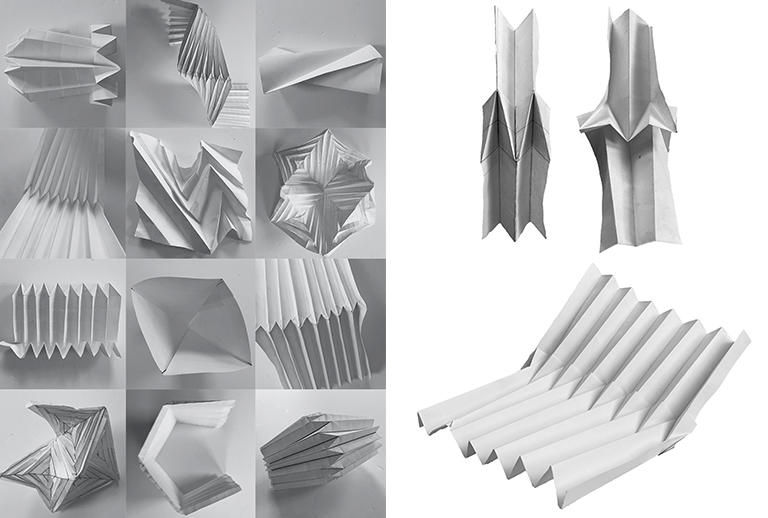

FOLD

Image

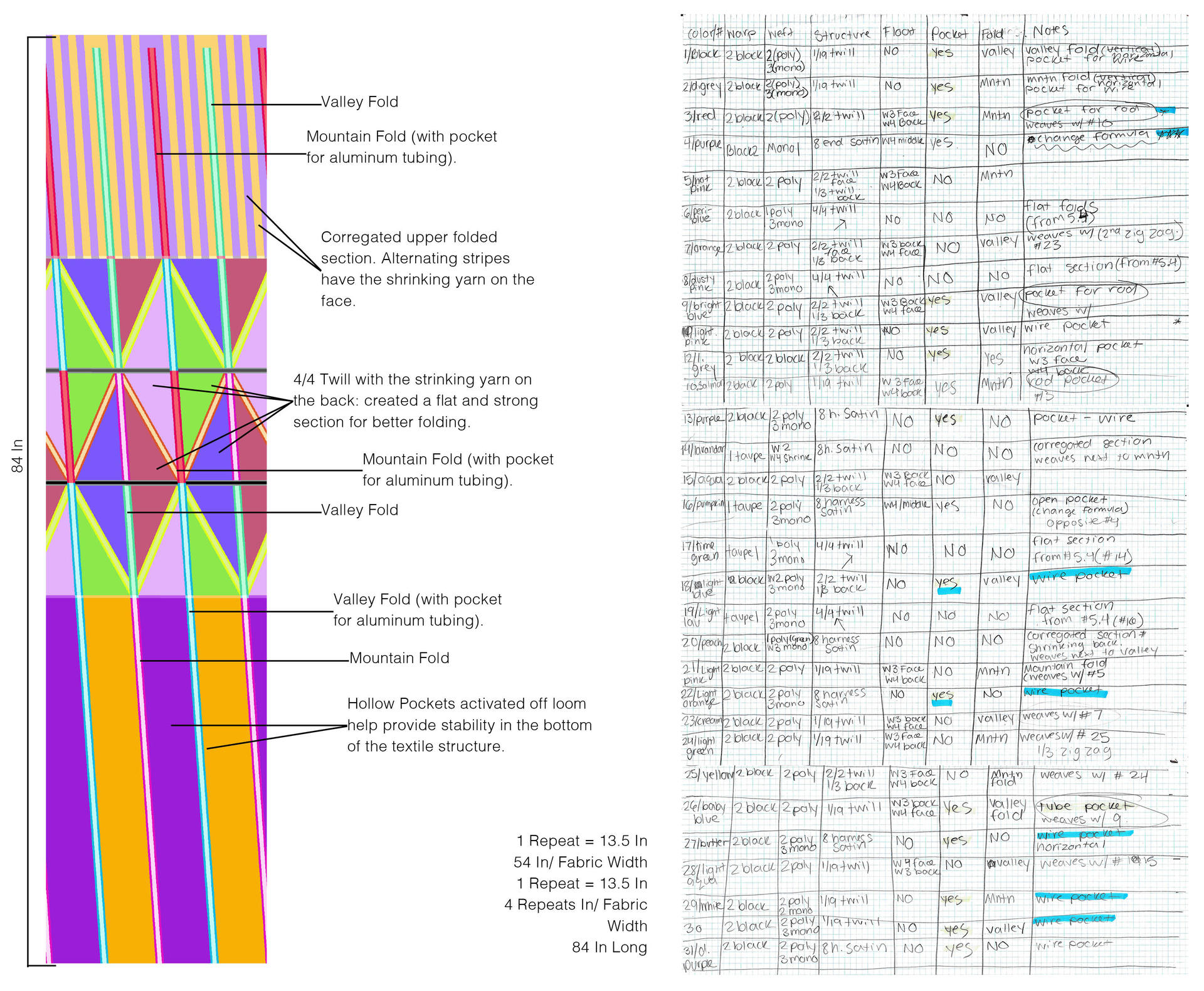

TRANSLATE

Image

WEAVE

Image

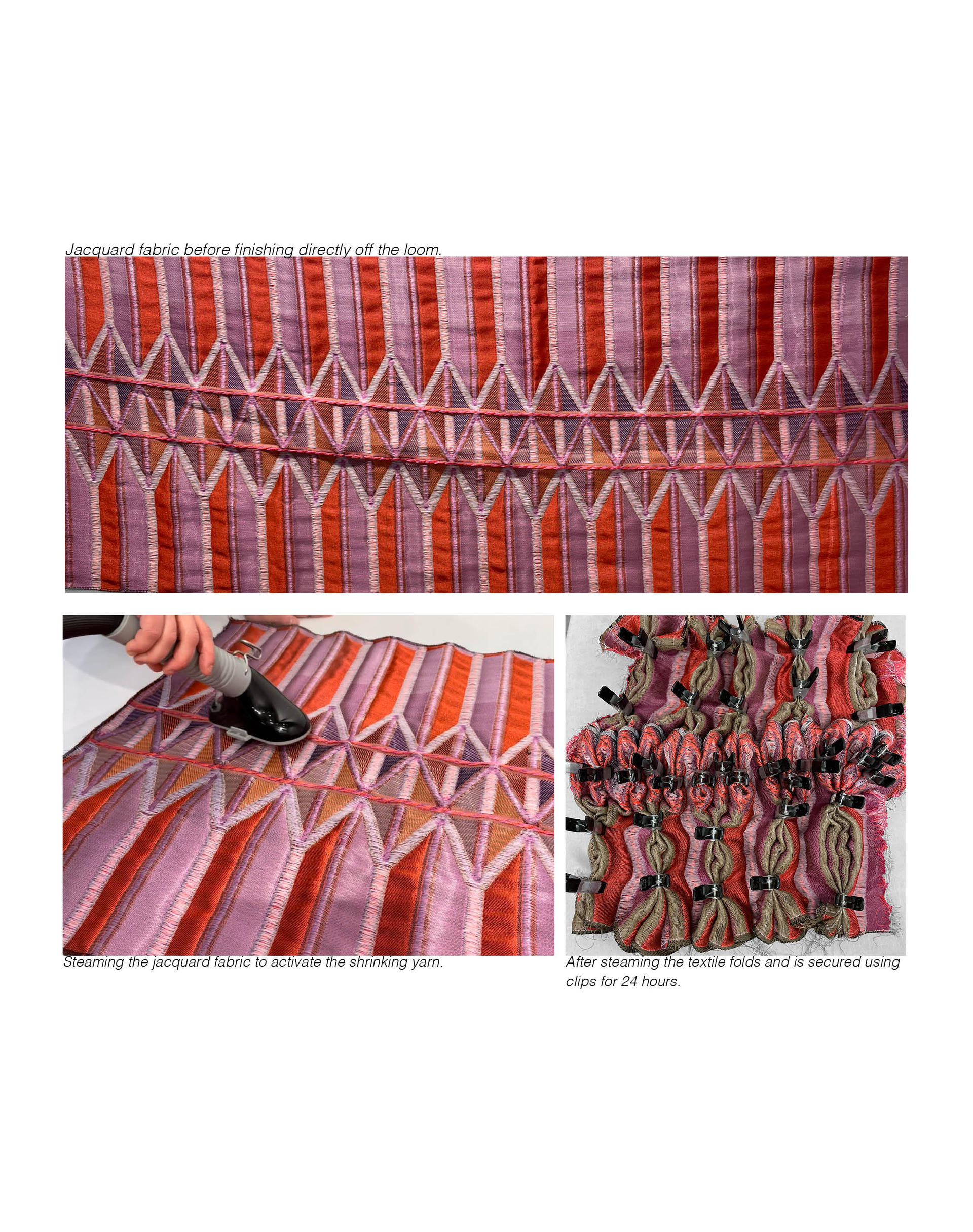

FINISH

Image

Image

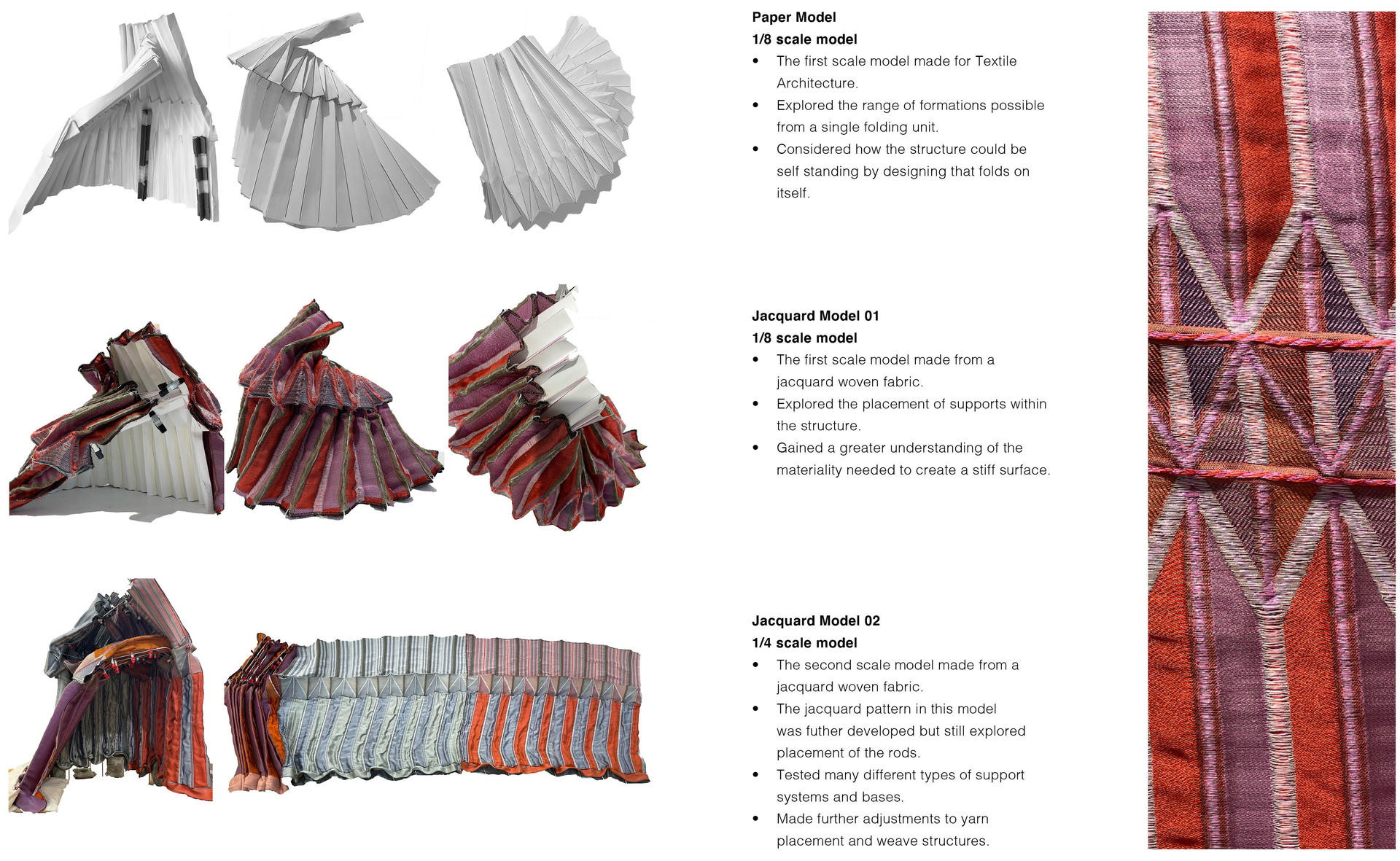

MODEL

Image

INSTALL

Image

Image

TEXTILE ARCHITECTURE

Image

Image

Image

Textile Architecture, 2021, Polyester, aluminum, and wood.

Textile Architecture is a system designed to create foldable, flexible, portable architectural space. Constructed from aluminum tubing, a wooden base, and a jacquard fabric, all of the technical components of the seemingly freestanding structure are hidden within the textile. The color combinations mimic the glimmer of granite, steel, or glass. At different angles, the light illuminates the line quality of the yarn, reinforcing variation in form through color and material. The inside of the structure is softened by a white band through the middle of the fabric. The contrast of the shadows cast by sharp, predetermined folds and the folded form causes a secondary pattern to emerge, one defined by the external environment. This subtle effect serves as a reminder that textile architecture aspires to live outdoors, alongside other systems of building.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

First image and all images in the Textile Architecture section are (c) Jo Sittenfeld, 2021.