Harsha Devaraj

Fertilizer Waste Mistreatment Facilities: Investigating the barriers that keep waste in and attention out at Central Florida's phosphogypsum stacks

When most people think of ‘waste,’ they picture trash and garbage. It comes as a surprise to most to learn that these everyday wastes - part of a category called ‘Municipal Solid Waste,’ compose only a tiny fraction of all the waste produced on earth. In the USA, only 3% of waste produced annually is MSW. The vast majority of all waste is industrial waste - a deluge of mysterious-sounding slimes, fumes, sludges, pebbles, pellets, and powders that is flowing out of industrial facilities around the world at unimaginable volumes. One such material is phosphogypsum - a powdery white byproduct of phosphate fertilizer manufacturing.

This project investigates the physical and narrative barriers constructed by the phosphate mining and processing industry to dissuade public engagement with its phosphogypsum sites in Central Florida, USA. The barriers around PG utilize decades of misinformation, racial geographies, and misrepresentations of scale, origin, and risk to create powerful narratives about how we should imagine and relate to these materials. These barriers hinder sustained public attention to their sites, enabling extractive industries to expand while avoiding oversight and responsibility. Attention to how these barriers around phosphogypsum are constructed allows us to recognize these strategies at work in how we see and communicate about industrial wastes, and opens up the possibility of new and more generative relationships with these materials.

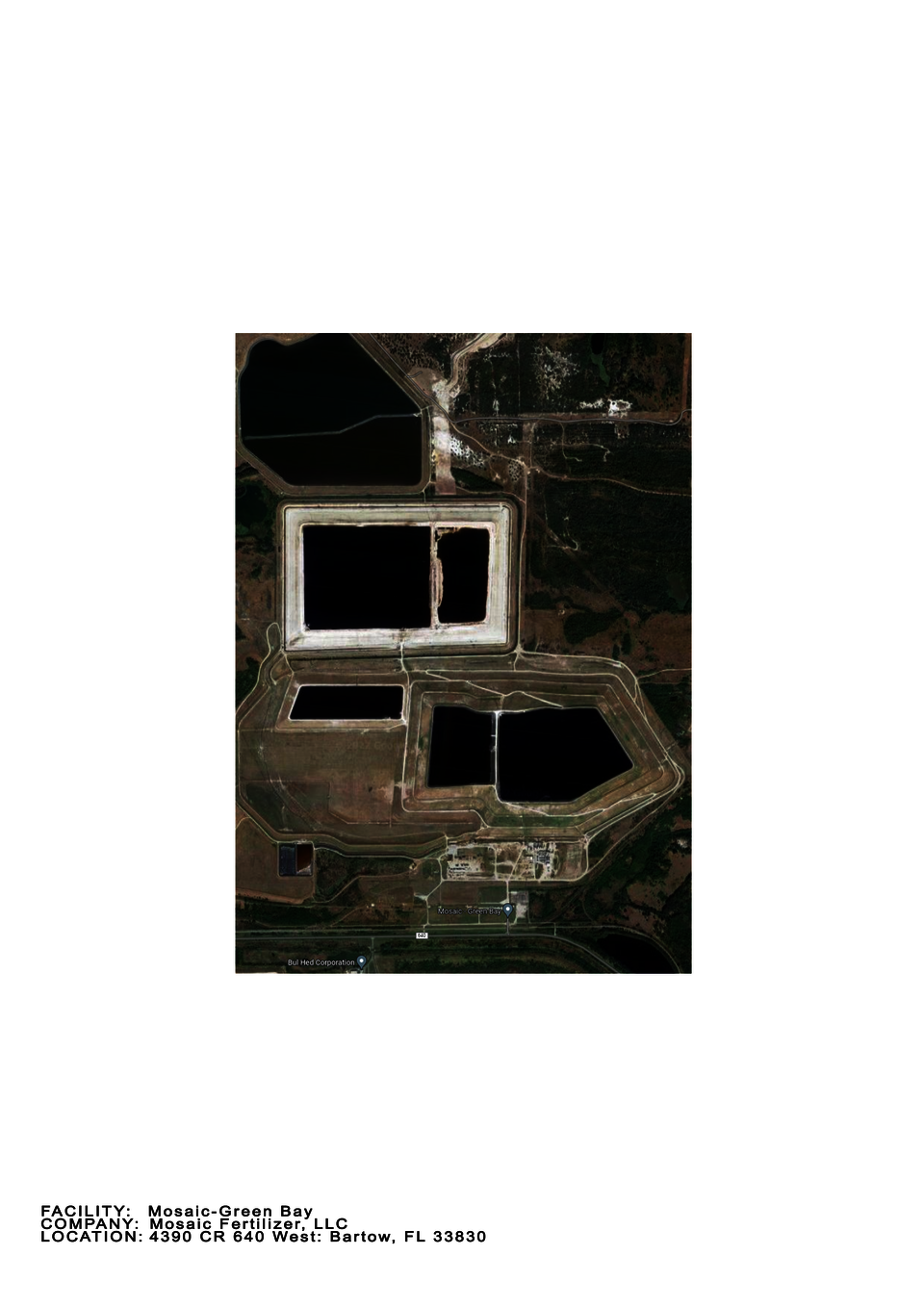

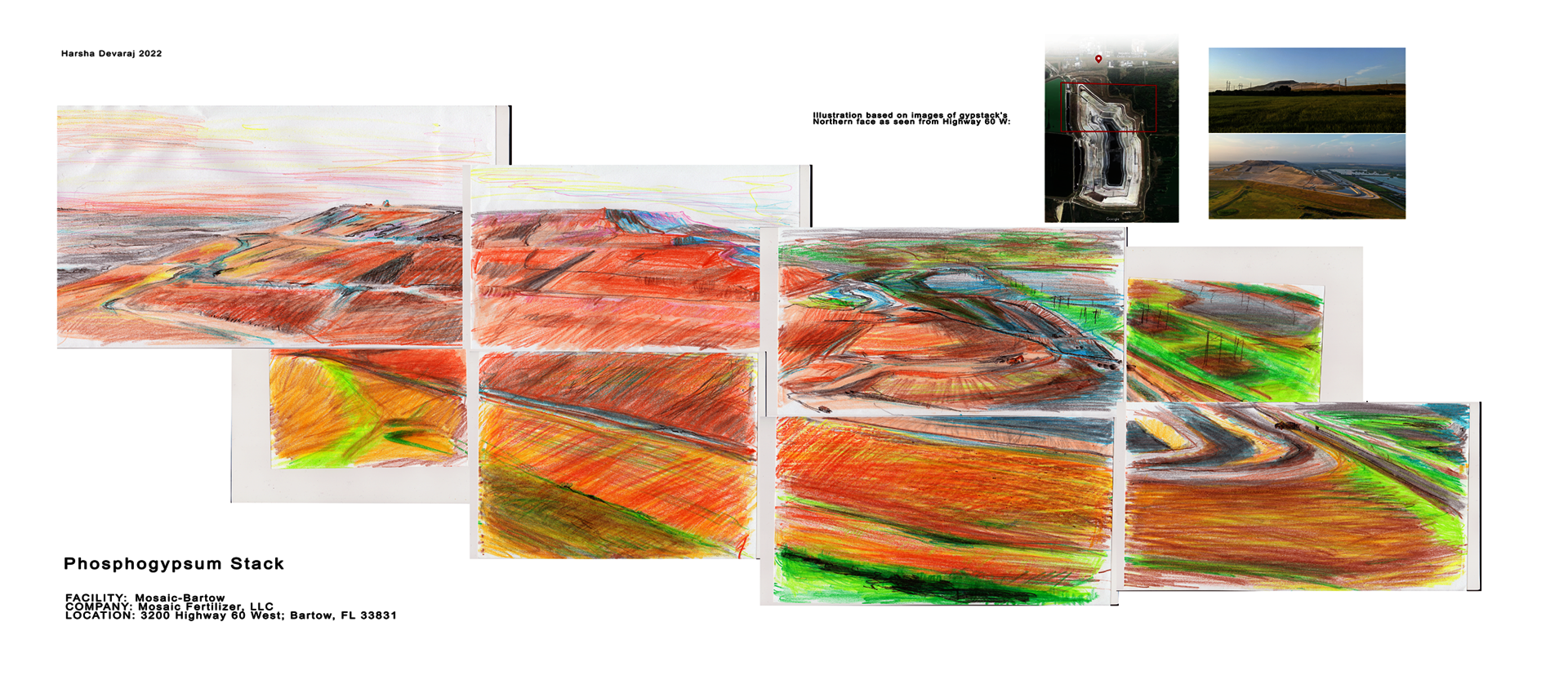

Image

Fertilizer waste stack, Bartow, FL

'Sink'

Imagine a kitchen sink. Your mental image likely includes faucets, a countertop, and a sink basin. Perhaps you also chose to include the garbage disposal system and P-bend underneath the basin. But what about the pipes that join the P-bend to the building’s drain - would you say they compose ‘the kitchen sink’ as well? What about the building’s main lateral pipe and the municipal sewer? At some point, you will likely agree, we are no longer talking about ‘the sink,’ and are describing the features of the broader drainage system.

Now imagine walking up to your sink and turning on the faucet, only to see the water in the basin building up ominously rather than draining out of the bottom. At this moment, you have no way of knowing where in the broader drainage system the blockage might be - it could be anywhere from the garbage disposal (-which is still somewhat part of ‘the sink’) to the sewer main that runs under the street outside (-which, we agree, is definitely no longer ‘the sink’). But when we see wastewater rising defiantly in the basin, why do we say, “The sink is broken/clogged/stuck”?

The reason that ‘the sink is broken’ regardless of the site of the blockage is because ‘the sink’ is more than just its physical components - it is also our name for the section of the drainage system that acts as the barrier between us and the realm of waste. In our small thought experiment, the sink is broken not because the faucet won’t turn or the basin is cracked, but because the waste is still here, and we are still worrying about it. The sink is broken because it has failed to send waste away. This example also demonstrates that these barriers are selectively permeable - the boundaries between the world and ‘away’ function differently for different people. A house’s main lateral drain might be alien to us but it is familiar territory to a plumber, who in turn does not follow waste-water into the domain of sanitation workers, and their municipal sewers and water treatment plants. Tracking the movement of materials after they have been designated to be waste reveals ‘disposal’ to be the process of moving materials across the boundaries that separate us from a deeper layer of ‘away,’ and transferring responsibility for the materials to that layer’s stewards. The black hole at the bottom of the sink, and other such barriers between the world and waste, are made possible by physical infrastructure and powerful myths - both of which require significant labor to build and maintain.

Building strong barriers around their waste is essential to extractive industries like phosphate mining and processing because it creates a blackbox within which the true costs of their products can be hidden, and where the risks of their operations are absorbed by the vulnerable groups conscripted to do the dangerous work of collecting and concentrating waste, and keeping it separate from other people. How and where are these nowhere-spaces of industrial waste built? What happens to people and materials as they move across their boundaries? What stories are told when ‘the sink breaks’ and the waste spills out? These questions become increasingly important as the volumes and complexity of industrial waste steadily grows, demanding a proportionate increase in the scale and complexity of the sites designed to contain them. New technologies must be developed to store these materials, more water, earth, and air be allocated to dilute them, more people recruited to work them, and more persuasive stories told to frame them. The study of these barriers is necessary to understand how, in the span of just sixty years, not just one by twenty five mountains of waste called ‘phosphogypsum stacks’ came to exist in the Central Florida without attracting very much attention at all.

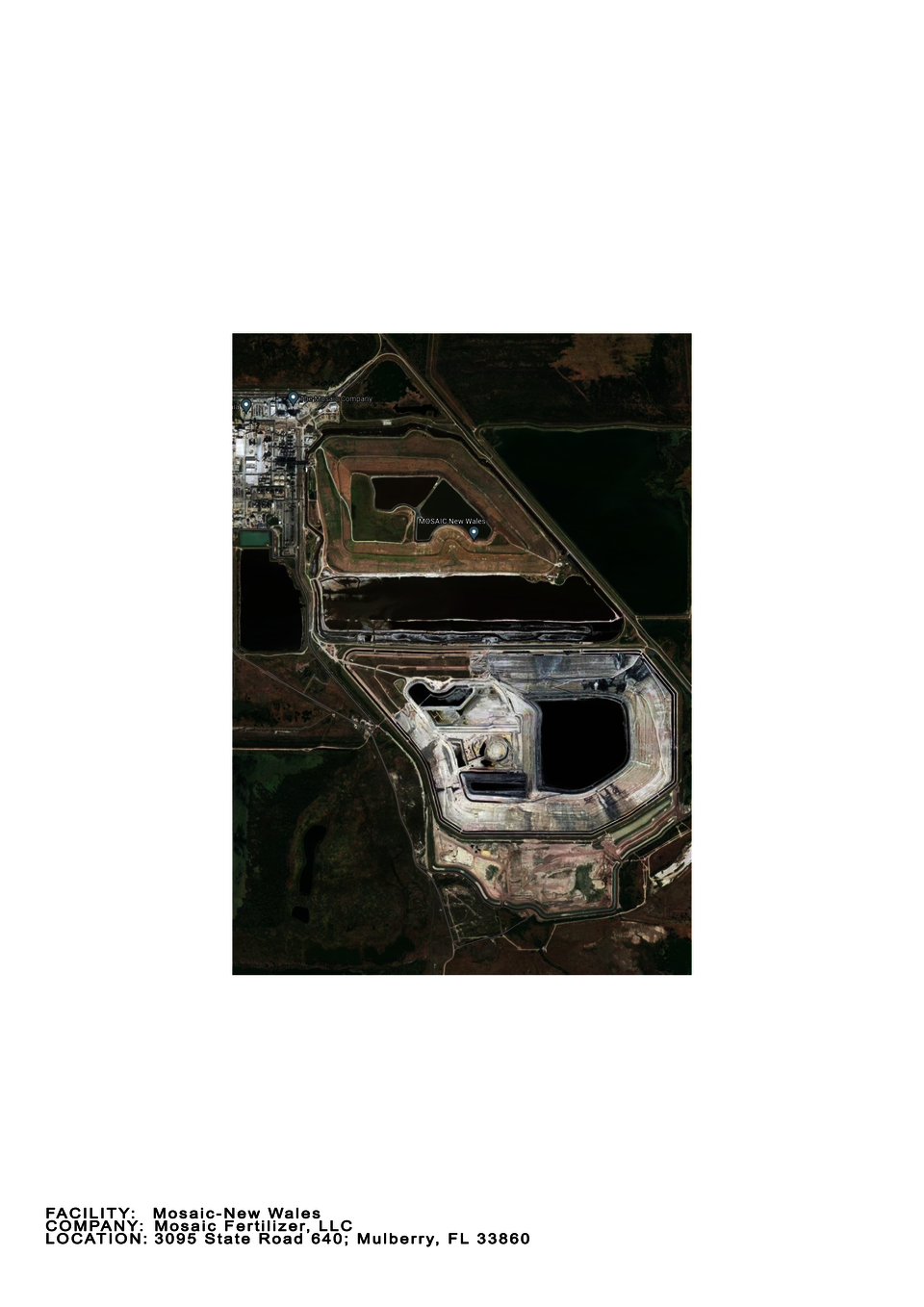

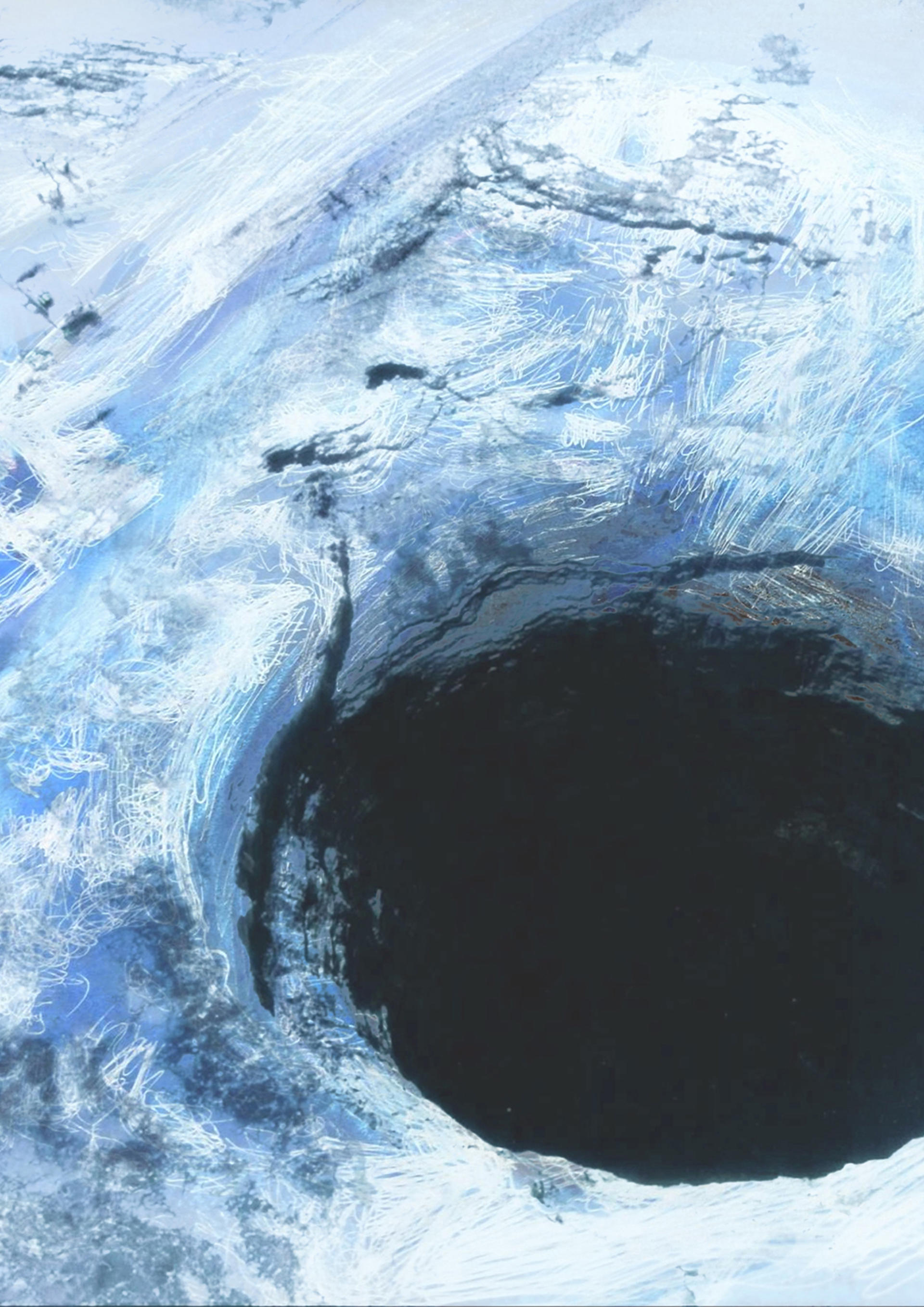

Image

Illustration of the 100-ft wide sinkhole that developed in 2016 at the Mosaic New-Wales gypstack

Phosphogypsum Stacks

Phosphogypsum is the byproduct left behind when phosphate rock, which is mined from the earth, is treated with sulphuric acid to extract its phosphorus in the form of phosphoric acid. This phosphoric acid is the primary ingredient in the manufacturing of synthetic phosphate fertilizer. PG emerges from the phosphate beneficiation plant in the form of a gray slurry - such as the one pictured above which is piped into vast, shallow reservoirs that have been dug nearby - each of which can span nearly three square kilometers (to put this in U.S. Standard Units, this amounts to approximately 400 American football fields). As the slurry settles in this shallow lake, its solids sink to the bottom, leaving some of the water to be pumped back and recirculated in the plant. The remaining water content of the sludge is allowed to evaporate over time, leaving behind an expanse of bone-white powder - this is phosphogypsum. These lakebeds full of PG more closely resemble the surface of the moon than any place on earth. In the satellite images below, we see trucks and earth-moving equipment as no more than specks in a sea of white sand.

These sprawling settling ponds, however, are not nearly sufficient to contain the volumes of PG that a typical plant produces. The modern industrial phosphate beneficiation process (known as the ‘wet process’) produces five tons of PG for every ton of phosphoric acid it generates. This staggering product-to-byproduct ratio means that there is simply too much PG to be spread so thin, and so a new reservoir is dug into the dry lakebed of PG, into which more slurry can be deposited and left to settle. This process repeats itself as many times as legal permits and the laws of physics allow, and lake by lake, new PG is piled onto old PG, generally reaching heights between 200 and 400 feet. These towering plateaus are called ‘phosphogypsum stacks,’ or gypstacks for short.

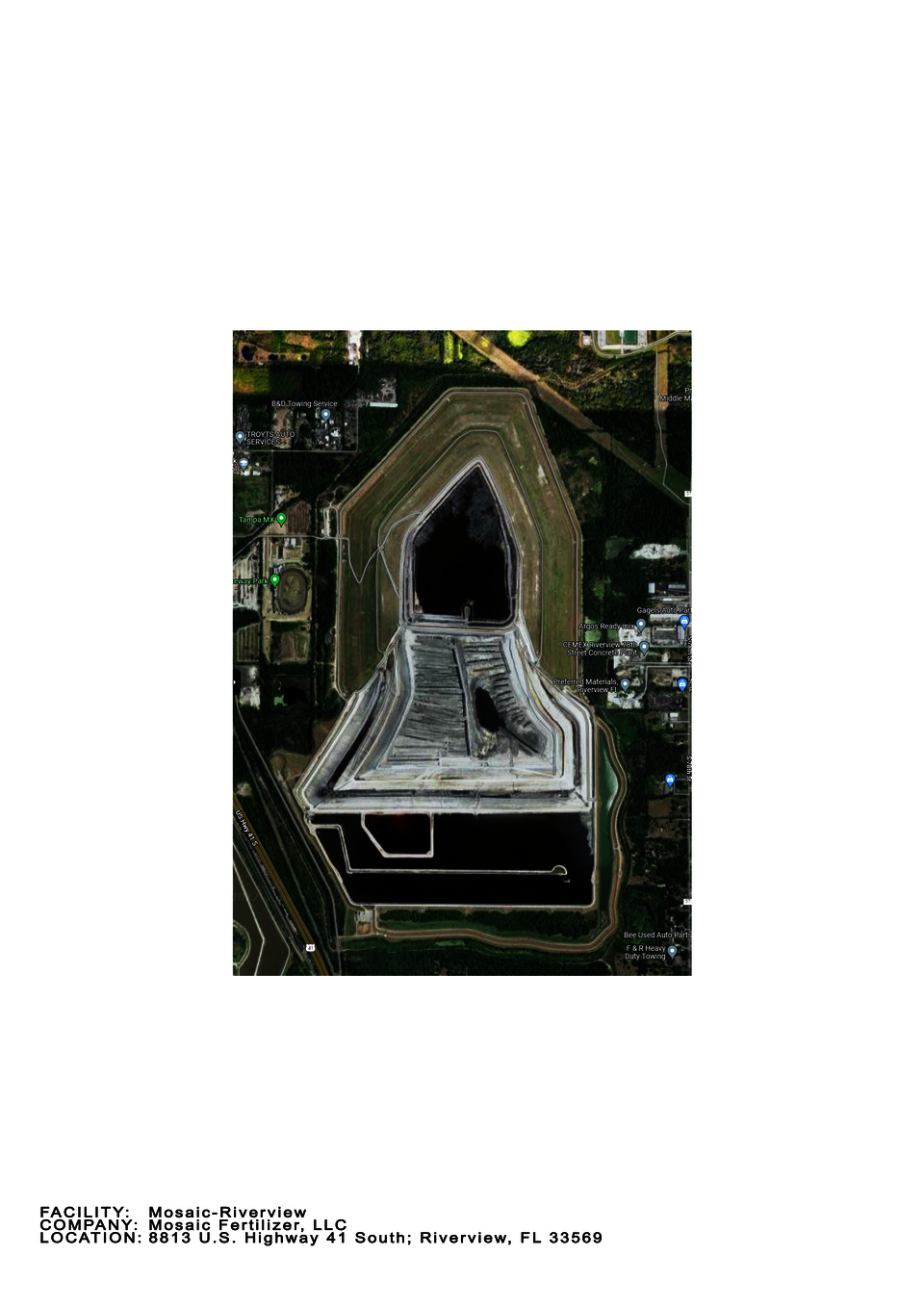

Image

View of gypstack in Bartow, FL from the road

Barriers around phosphogypsum

In the rich body of scholarship that exists on the intersection of waste and ignorance-production, much attention is dedicated to the methods by which waste is hidden, burned, buried, sunk, sealed away- in other words, made to be invisible. The widespread ignorance around phosphogypsum is particularly fascinating because it could hardly be more conspicuous. It is stored in towering structures that dominate the horizon of Florida - the flattest state in the USA. The pale walls of phosphogypsum stacks rise in stark contrast to their surroundings, and their geometric construction marks them as clearly human-made despite their geological scale. How does an industry deal with its waste when the material refuses to be pushed out of sight? The answer in the case of phosphogypsum is to ensure that the inevitable encounters with phosphogypsum are fleeting. The barriers around PG are not intended to conceal so much as they dissuade sustained engagement - through various means, they ensure that PG is ‘slippery’ from every angle of approach.

My thesis investigates three barriers between the general public and phosphogypsum. The first barrier is the concentration of PG’s risks in Central Florida, in and around the state’s poorest and least White neighborhoods. Far from the coastal vacation homes and tourist spots that form Florida’s public facing image, these low-income communities across Bone Valley are largely isolated from systems of legal, financial, and political power. As the broader public in the USA is already largely disengaged from topics of industrial waste and food systems, it finds little reason to engage with PG while it remains within these boundaries.

The next barrier consists of narratives about PG’s origin and purpose. This barrier is intended to deter those who inevitably stumble onto the sites and stories of PG and attempt to learn more about the gypstacks and how they came to be. Phosphate companies misrepresent the relationship between food-production and food-security, and mobilize the unfathomable numbers involved in their modern industrial processes to argue that the current methods of synthetic fertilizer production are vital to ensure the survival of humanity on planet earth. Phosphogypsum is framed as an unfortunate but inevitable necessity in service of this goal. This narrative is further strengthened when activists and journalists attempt to convey the dangers of phosphogypsum without first interrogating this industry narrative about synthetic phosphate fertilizer and global food security. As a result, industry narratives and environmental writing come together to frame phosphogypsum in a deeply unsettling way: as a calamitous threat for which there is no alternative - an emergency about which very little can be done. I argue that this discourse is a powerful deterrent to sustained engagement with PG.

The third barrier works to define ‘the problem of phosphogypsum’ as a problem of improper containment. Occasionally, an event takes place involving phosphogypsum that is so drastic that there is overwhelming public pressure that some action must be taken to address it. This most often occurs when an ‘accident’ takes place at a gypstack - most people are introduced to PG by the new reporting in the aftermath of these incidents. During this period, industry’s press releases will work to minimize the danger, and news reports will attempt to convey the true scale of the incident, but both these opposed sides will use language that shifts responsibility and blame onto the waste-substances involved, and away from the industry that produced them. The language of ‘accidents’ and ‘gypstack failures’ strengthens the idea that better, more secure gypstacks would ‘solve’ phosphogypsum - even though doing so would only return it to its containment sites where it, and the communities entangled with it, continue to bear the weight of a fundamentally unsustainable and exploitative global industrial agriculture system.

Studying the barriers around phosphogypsum, one is confronted with the shortcomings of simply conveying the existence, scale, and danger of industrial waste as a strategy of attracting attention and generating engagement with these complex and urgent materials, their sites, and their respective industries. The effectiveness of the barriers around PG suggest that when an entity is revealed, only to then be deemed uninteresting or inaccessible, it can become lost in a profound and lasting way. For industrial wastes to gain the attention that they deserve, the construction of these complex and mutually reinforcing barriers must be first recognized and addressed.

Gypstacks around Florida

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles