Rachel Cobler Wollert

Un-Done: The Historiographical Dialogue Between Past and Present

Art critic for The Nation and professor at Columbia University, Arthur C. Danto led the charge with his essay “The End of Art” in 1984 to declare the end of art. Thirty-eight years later, the awareness of colonial problematics in the elite institutionalism of art history today warrants a reanalysis of art historical ontologies of progress (and their ties to colonialism), which have seemingly disbanded in the discipline’s current rhetoric. Because Danto’s historical framework to end art focuses on progress through artistic means, does it fall short or even negate itself by missing the deconstruction of colonial afterlives still present in art institutionalism? Moreover, does Danto’s end to art ultimately reiterate colonial and imperial dictations over time, and thus undercut a historical futurity for “non-Western” “artists”? In comparing Danto’s theoretical discipline with the work of Titus Kaphar, Yuki Kihara, and Jason Garcia (Okuu Pin), I present a hypothetical dialogue between the art historical constructs of time and the present investment in decolonizing art with a critique through appropriation. Kaphar’s work underlines how representation can challenge the game of identity performance for the benefit of institutions, Kihara challenges the pervasive ignorance towards stereotyping Pacific Islanders by resisting and confusing the West-East binary boundaries, while Garcia challenges the hero complex historical figures still have in popular culture even if they are academically deconstructed. Ultimately, they perform a legitimacy to an end of Western hegemony that Danto alludes to.

The End of Art?

If you’ve ever come across an opinion piece where an art critic proclaimed that a certain medium or genre was “dead”, the idea might seem strange and disorienting. For the philosopher and critic Arthur Danto however, an end of art was different. As Danto wrote about the Art world in the late twentieth century, he mused in his essay “The End of Art” that the ways in which art was expected to progress could no longer be maintained in light of how art was turning into a philosophical measure of defining itself. The Urinals and Brillo Boxes were evidence that art could be as infinitely pluralistic as life was. Therefore narratives of progress which had shaped art history for centuries were no longer relevant. Art itself would continue, but its directional heading was absolved.

Looking at this essay as well as Danto’s relevant texts on the subject raises some crucial questions as to the relationship between art history’s narrative, the end of art, and neo-colonial structures of time and place. The artistic necessity to re-engage colonial and imperial aesthetics through appropriation lends to this discussion of what is created or undone through Danto’s theory. It shows how some artists would need to deconstruct an imperial and colonial narrative of history that continues into the present despite the end of art’s impact on the contemporary Art world. My thesis examines the following questions using a selection of contemporary art as a metric of discussion:

Is Danto's theory universally applicable to art? That is, is Danto’s theory claiming that a Western-centric mindset in art history has exhausted itself and now art can be liberated from its prescriptions? Or is Danto presumptuous to rely on a reductive art history and claim the end of all art from its climax?

Has the application of the end of art actually dissolved and disbanded art history’s positions of progress? Is progress still necessary?

The aim is not to derive a black and white conclusion of whether Danto’s theory is flawless, but to consider how this kind of juxtaposition can render a more anti-colonial praxis for both art theory and making.

Titus Kaphar, Yuki Kihara, and Jason Garcia (Okuu Pin)

These internationally acclaimed artists all use a fascinating practice of appropriating other paintings, artists, and genres to deconstruct a colonial lens on cultural identity. Specific events preserved in painting, photography, and a festival originally present a glorified lens of the colonizer; in the artists’ hands they shift identity, add crucial context to history, and question the motivation of narrative. This simultaneously affirms Danto’s position of exhaustion in art historical narratives and complicates its singular measure of aesthetic progress by adding one of equitable representation.

Titus Kaphar’s Crumpled series copies paintings and then transforms them, sometimes marring the new painting beyond recognition. Several examples refer to portraits of Elihu Yale, the founder of Yale University, Kaphar’s alma mater. Whereas Yale’s original portraits are meant to highlight his wealth and status, Kaphar unveils the implications behind that display. Enough About You layers this identity shift with the repainting of a young African boy. The marks of slavery are replaced with fine clothes, changing his identity. By shifting the subject and the framing (sometimes literally) of his paintings, Kaphar poses a skillfully woven answer to a national dichotomy of removing or preserving colonial monumentality.

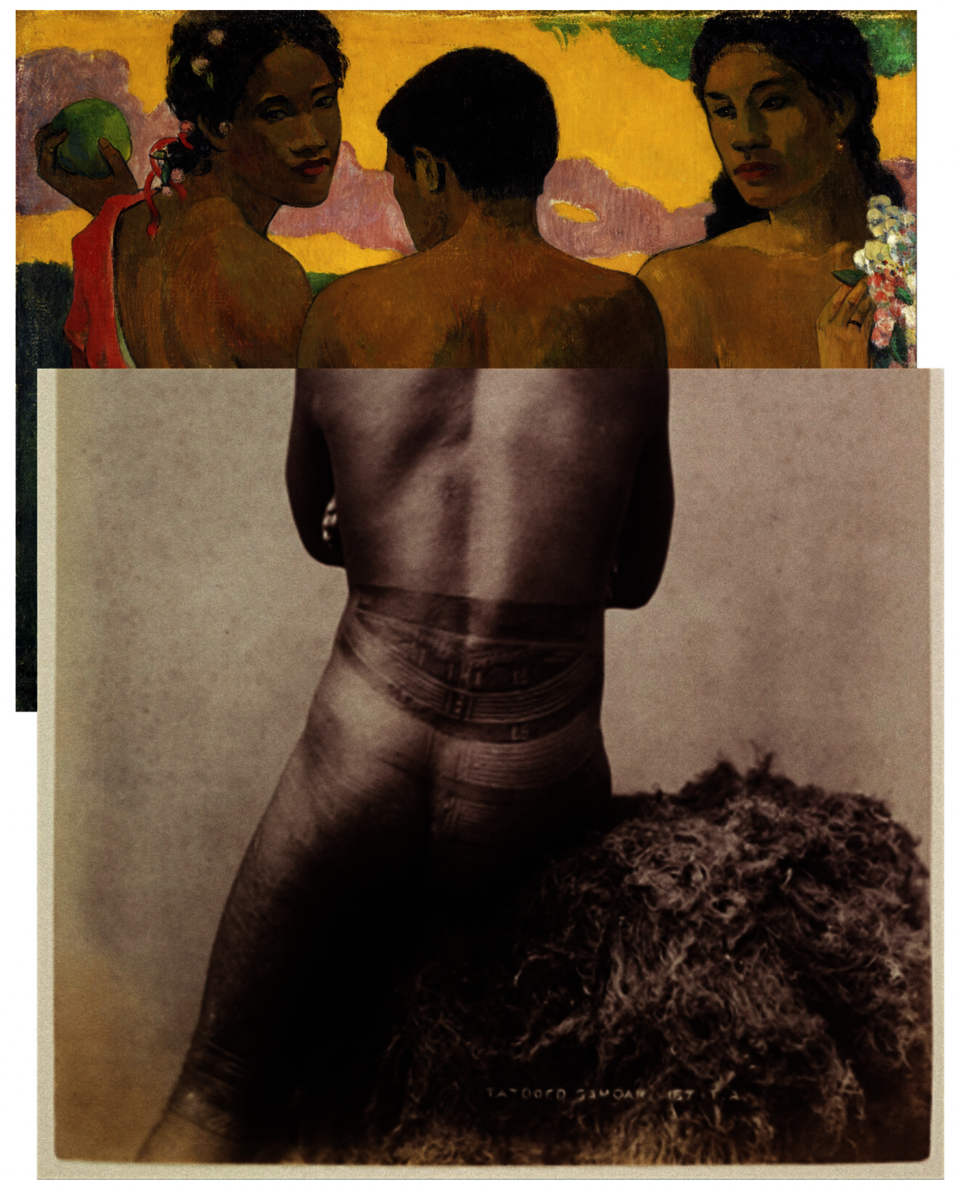

Although Yuki Kihara’s range of dance, curation, collage, and video mediums inform a global audience of Pacific Island heritage, many of her works address the ramifications of colonial influence through an association with Paul Gauguin. Although Gauguin’s visits to the Pacific Islands never included her home country Sāmoa, Kihara relates Gauguin as a marker of reference to address the generationally persistent problems of Pacific identity including gender identification, exhibitionist exotification, and paradisiacal sublime. Splicing his paintings with photographs, Kihara reveals how both mediums developed a double bind of exotic yet whitewashed versions of identity. In her own photographic series Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?, Kihara’s persona of Salome complicates the distinctions of colonizer and colonized. Instead of attempting to present a somehow pure, uncolonized version of Samoan identity, she strategically layers the colonial assimilation with a repeal of the exotic gaze and depictions of colonial architecture with wrecked landscapes to counter the stereotype of paradise.

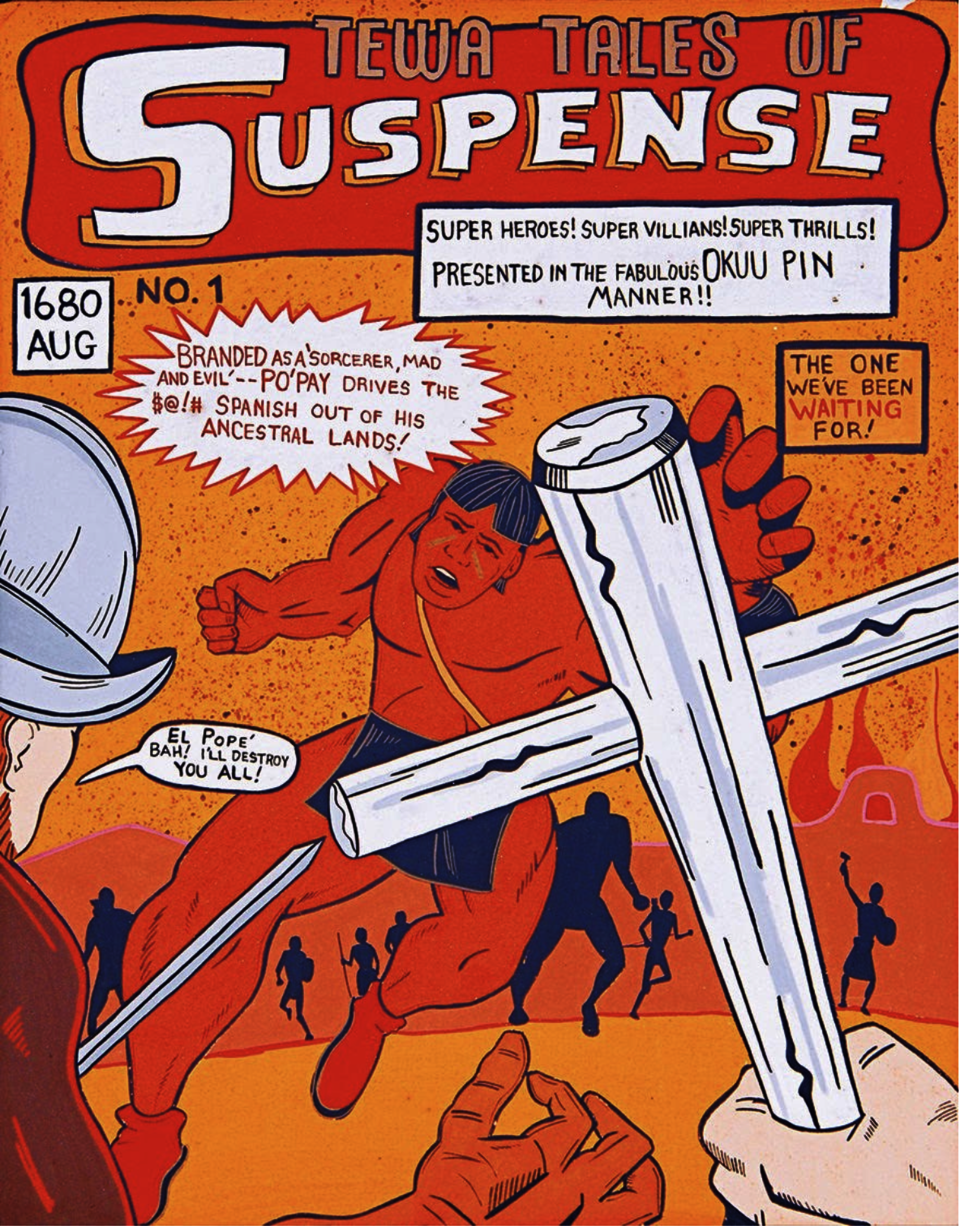

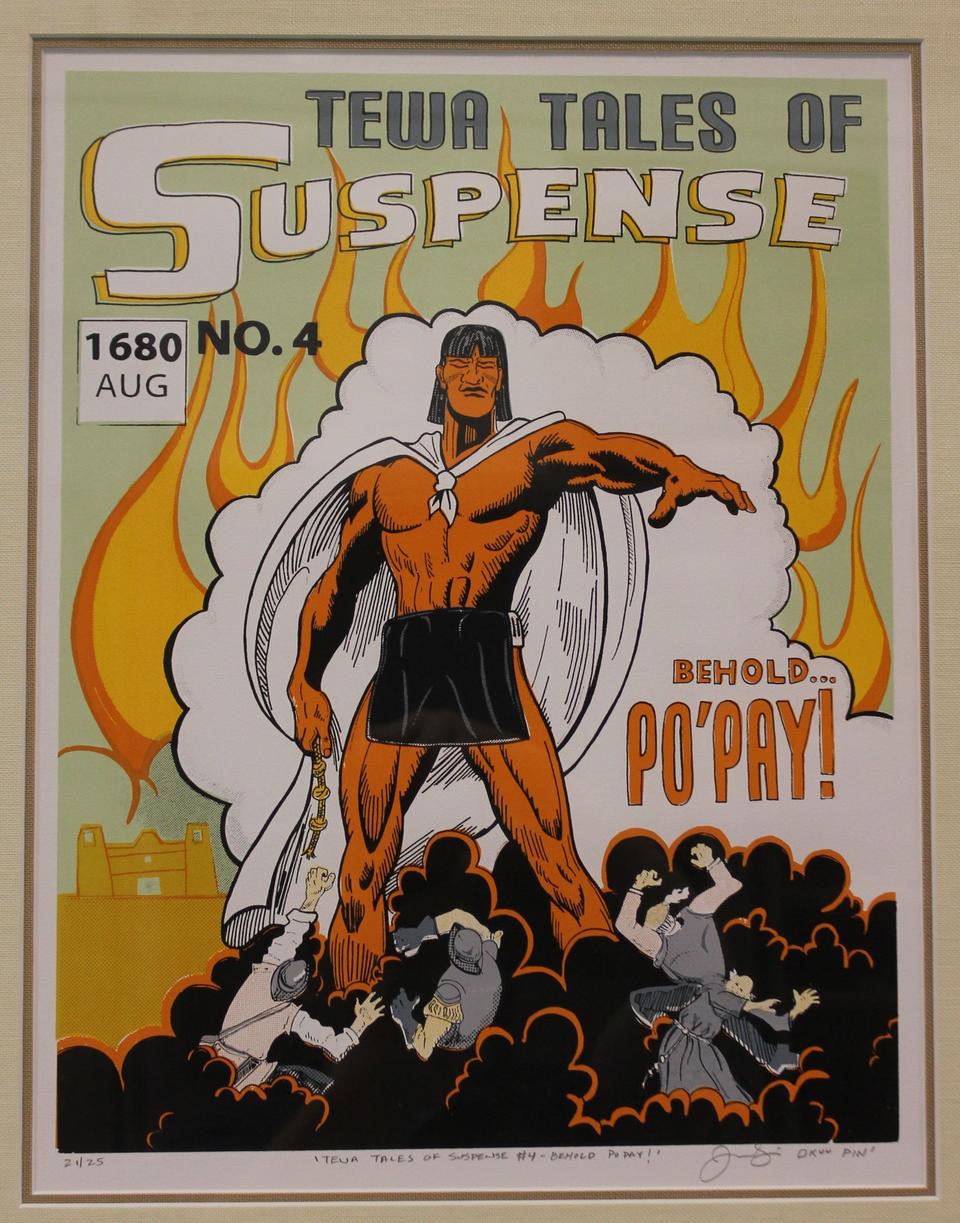

In his ceramic and print series Tewa Tales of Suspense, Tewa artist Jason Garcia recalls the battles of Pueblo Revolts against the Spanish in the 17th century. Festivals in the Southwest today mark these events as nonviolent, parading saints and conquistadors as protagonists and benefactors. By incorporating the dynamic smash-and-slash design of mid-century comic books, Garcia can recount history in a medium appealing to young generations. While he references some superhero stereotypes, his indigenous characters are constructed to divest from a neocolonial mythos of power that pervades in comic book narratives.

Artwork

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles