Jason Hebert

Story Framing: An Exploration in Storytelling

Grounded by Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s definition of struggle (2012); this body of work evaluates the role of visual, verbal, and visceral storytelling in engaging the imagination as a language of possibility outside that of colonialism. It begs the question: how might we decolonize our minds, bodies, hearts, and spirits by (re-)engaging with and (re-)embodying the stories that we are involved within? In exploring the stories of our pedagogies, positions, perspectives, performances, and praxes through the storytelling frames of growing, threading, webbing, weaving, and braiding does this thesis create space for deep learning and disrupting cognitive imperialism. Furthermore rooted in Jo-Ann Archibald’s seven principles of Indigenous Storywork (2008), all investigations conducted have committed to Indigenous methodologies, ontologies, epistemologies, and axiologies. Governed by decolonial thought, expressed through a collection of personal stories, and manifested in a beaded talking stick; I have further considered the role of (higher) education and local youth engagement in the creative act of story framing. In storytelling, we become who we are meant to be – framing them in the right way can help ease that process.

Image

As a more-than-human teacher, this talking stick has served a vital pedagogical role throughout this thesis work. Originally a dancing staff, it was re-beaded to tell a new stories, express a new spirit, and facilitate community storytellings.

Introduction

The stories we experience, tell, hear, and share make up our understanding of the world(s) we live within. We communicate our thoughts with our verbal stories; our bodies telling different ones in tandem. In this sense, how do we make space for us to creatively express and embody our stories? This thesis work looks at how we frame our stories with an additional focus on holistically developing a balanced spiritual, mental, emotional, and physical sense of self through them. Particularly, this work draws a boundary around exploring five key story concepts through five story frames. These are not all inclusive but rather simple stepping stones. Importantly, this is all coming from my subjective experience working through my own stories, story frames, and storytellings. It is descriptive, not prescriptive.

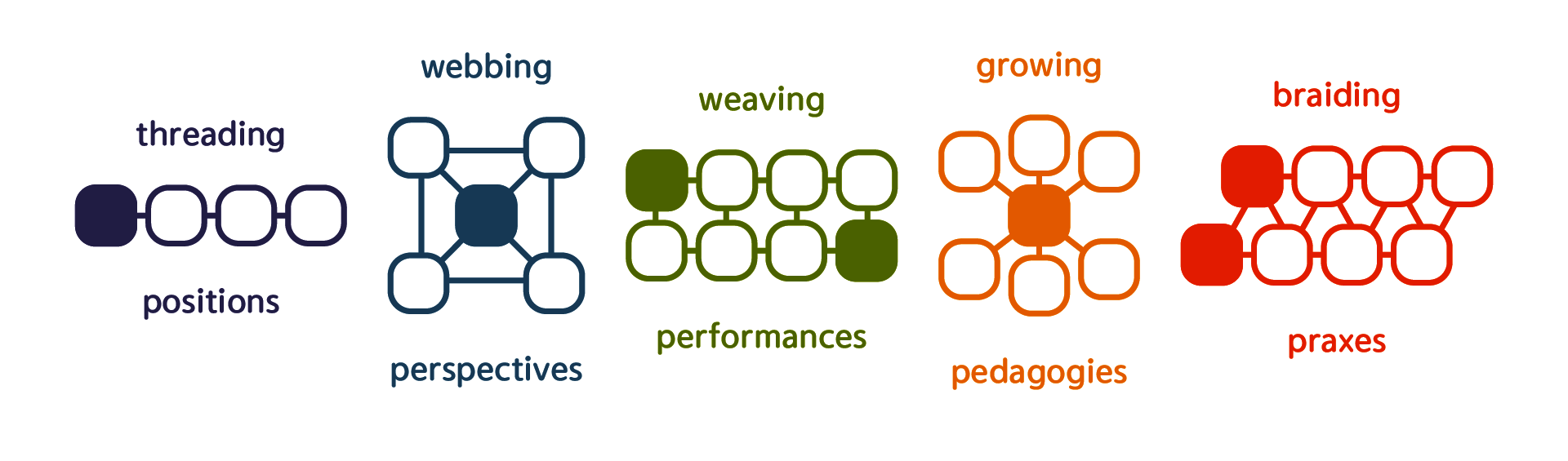

The five key spaces include our pedagogies, positions, perspectives, performances, and praxes. The pedagogy is central for this work and focuses on enskilment, holistic teaching, and (un/re)learning. Our positions make up our relationships within time, space, and extended kinships. Our perspectives constitute our understanding of the worldviews we have encountered, the cycles we exist within, and the animacy of our language. Our performances look at the ways we experience and express our overlapping (e)motions. Engaging our praxis of the work centers on site-specificity, mutual trust and benefit, and following protocol.

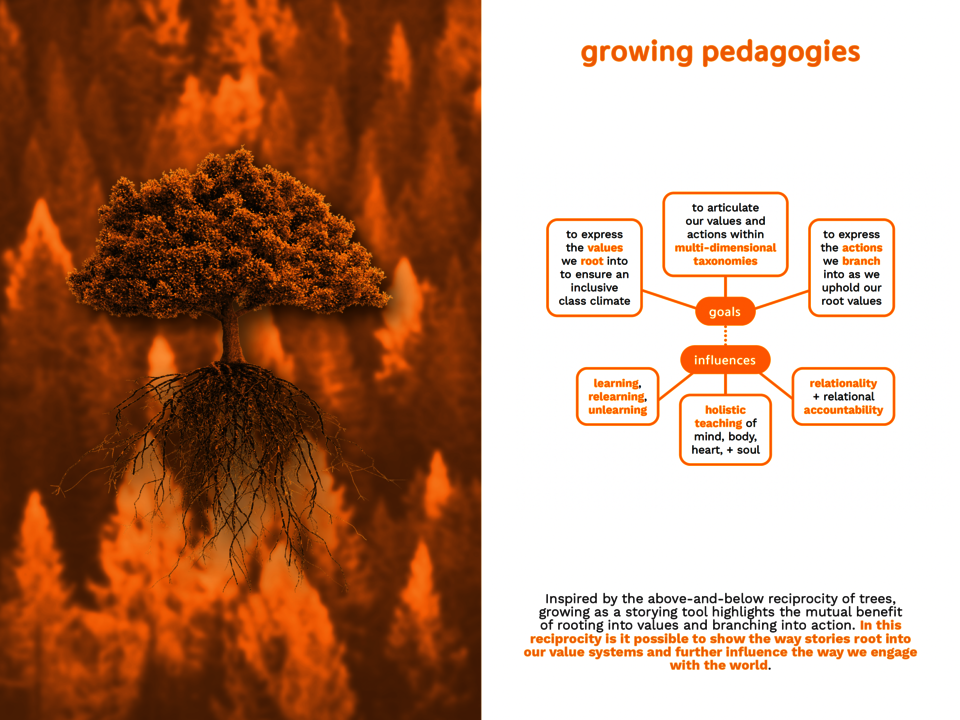

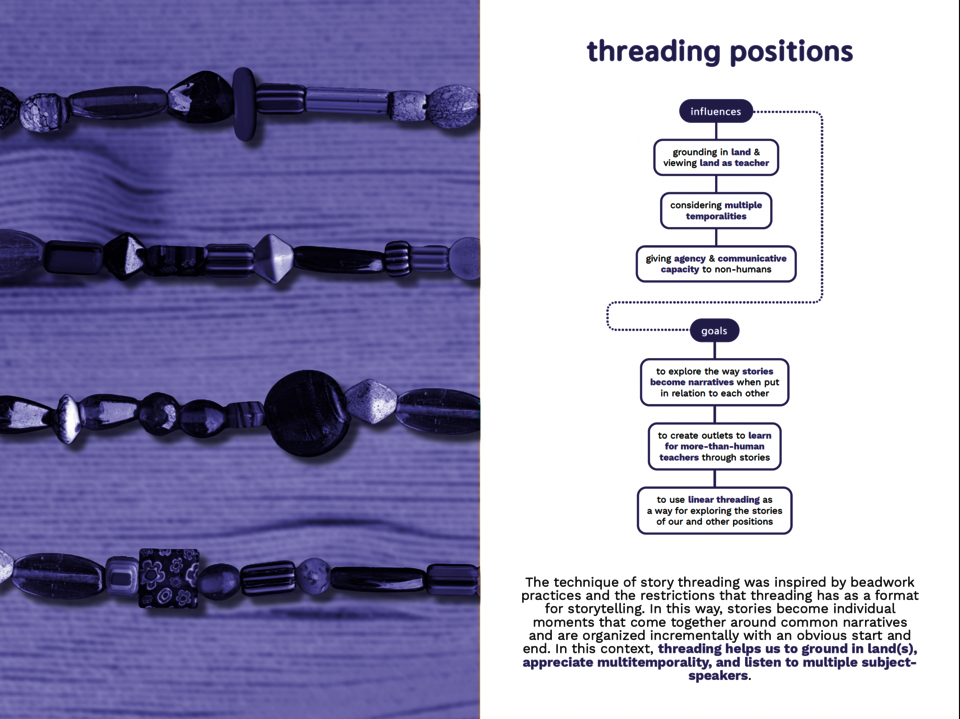

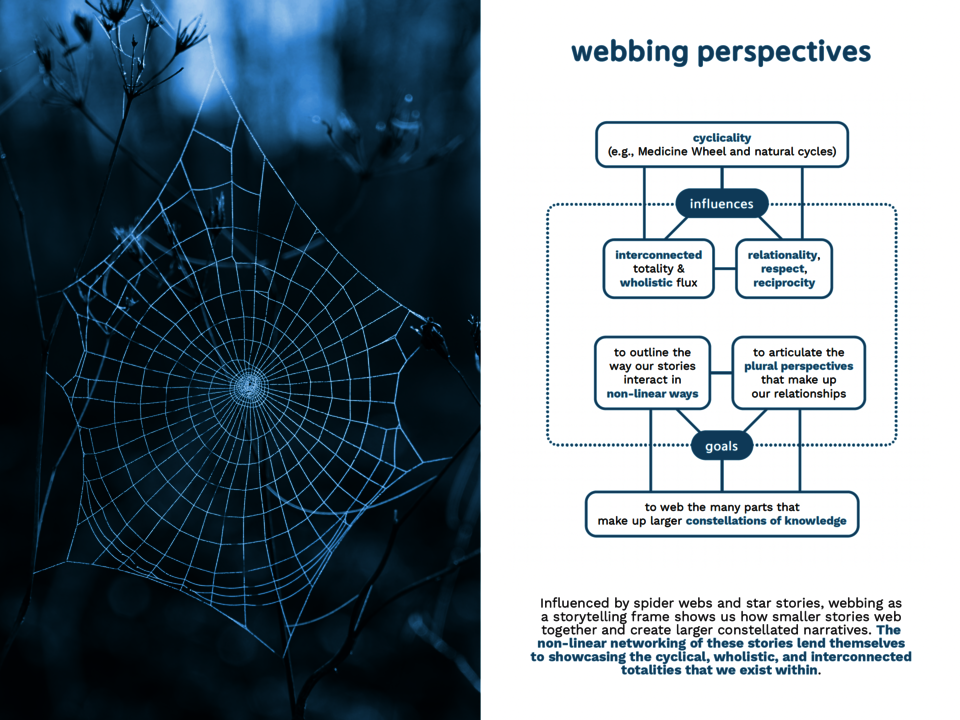

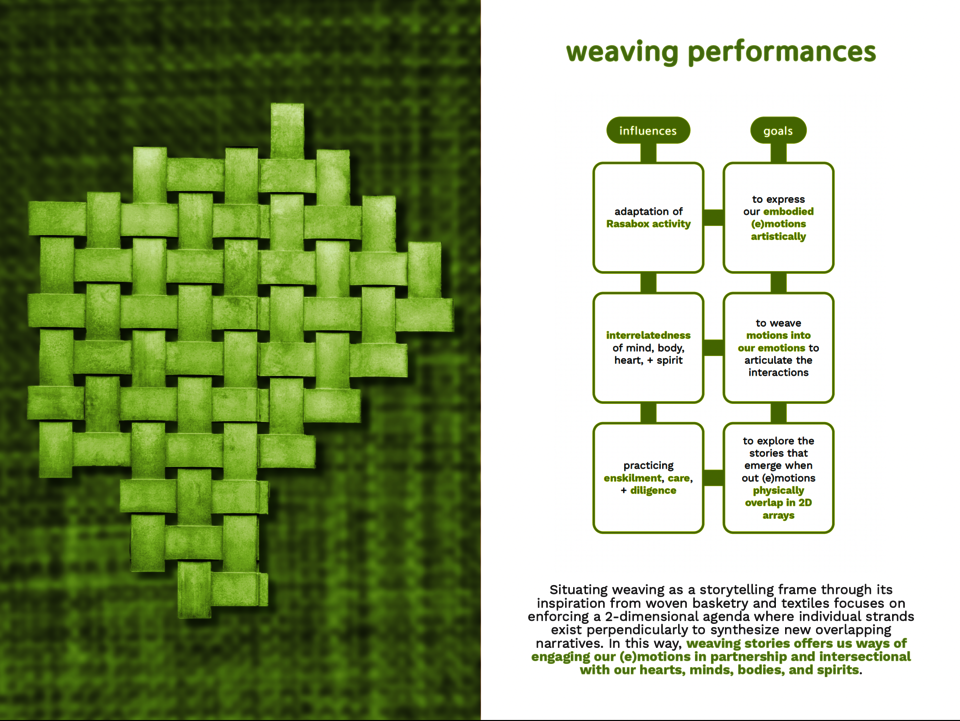

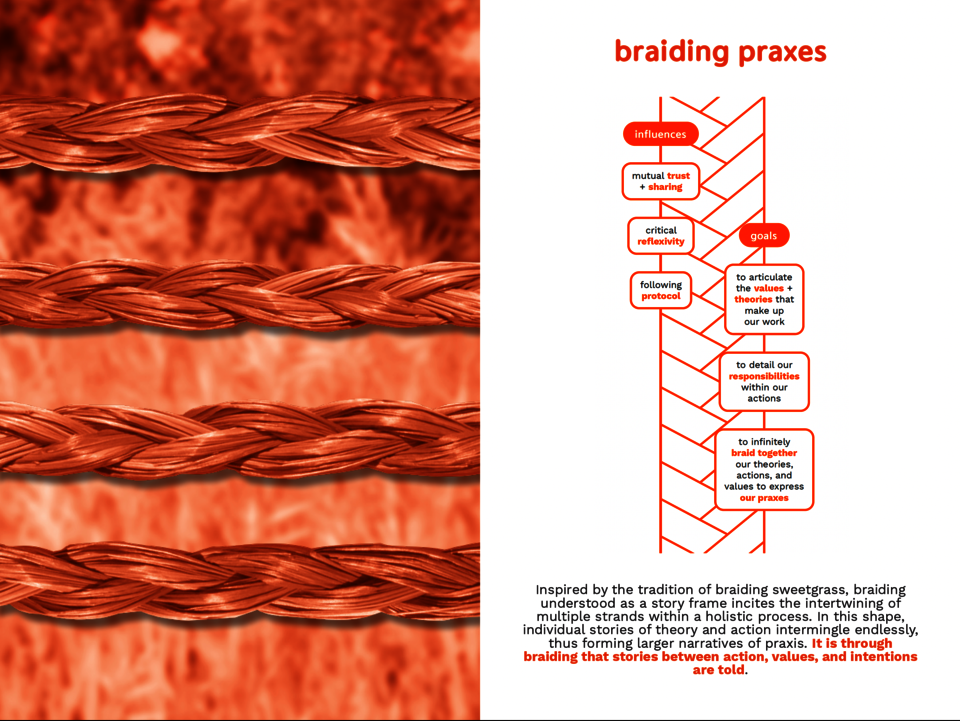

To explore these story spaces, I have worked through five distinct storytelling frames, each of which offer certain constraints which benefit some stories while bothering others. Growing conceptual trees teaches us to root into our value systems and branch into action. Threading our stories shows us the way they are related linearly. Webbing them breaks that linearity, offering boundless interconnected possibilities. Weaving stories shows us their overlaps. Braiding intertwines them together showing the limitless relationships between parallel stories of theory and action.

For gauging its value, this work has engaged underrepresented identities within the creative field through storytelling exercises. By collaborating with Project Open Door, youth in the Providence area in a workshop were involved in the creative practice of land-based storytelling. Otherwise, this work has been developed in tandem with art and design students at ranging levels within a higher education setting. In particular, much of this work grew from a self-designed collegiate-level course, titled Postcolonial Explorations, which engaged RISD students with these story frames and contents. In addition, the entire narrative of this work was distilled within a talking stick, which became an important more-than-human teacher.

By expressing these content-centric story spaces through relevant technique-centric storytelling structures, this thesis exists as a collection of personal stories. It is a unique manifestation of the role of education and community engagement for balancing our senses of self through the stories we creatively and critically tell. It is raw and incomplete, but it is the first few steps in a longer personal and communal exploration.

Image

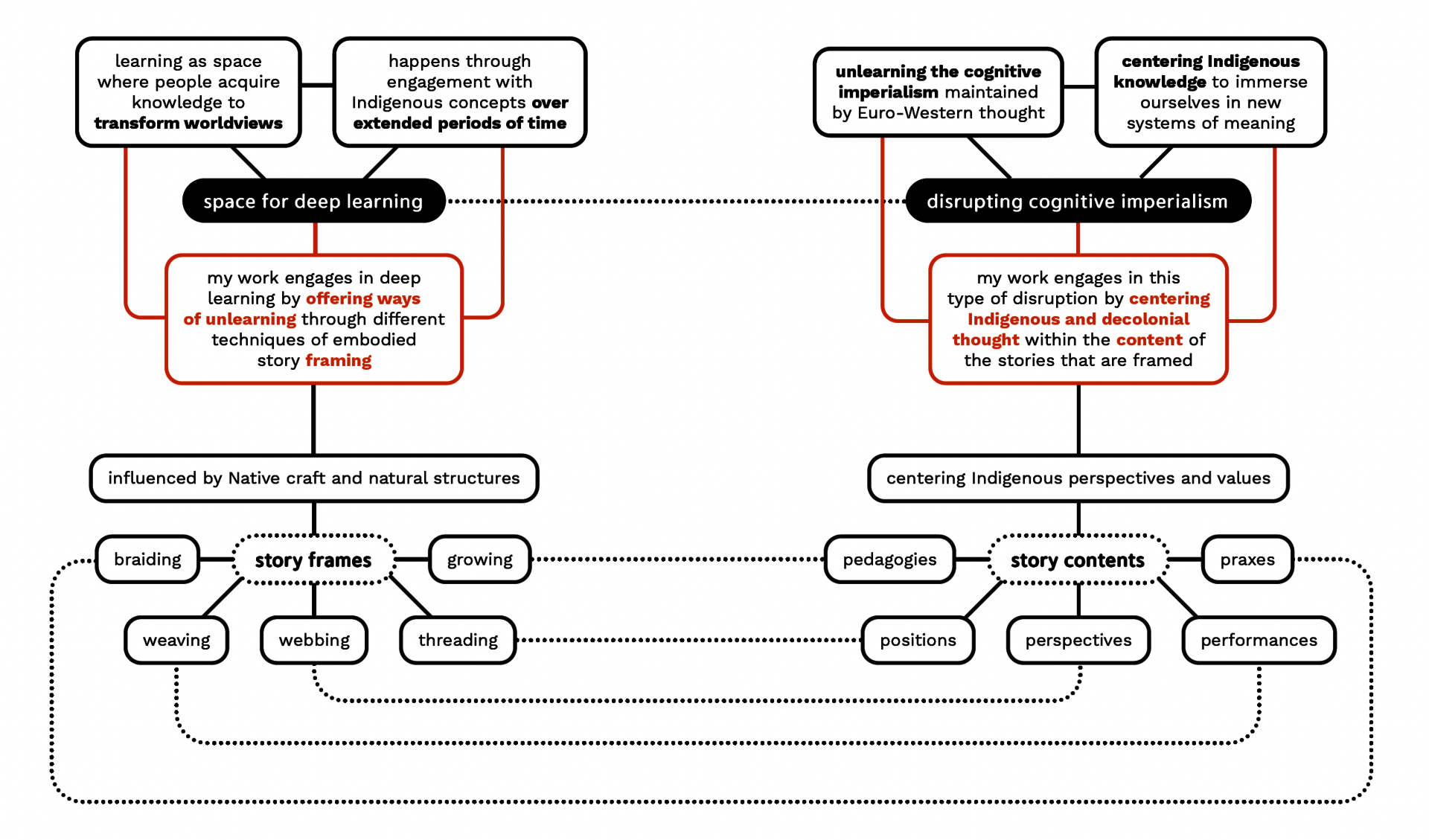

Diagram illustrating the five story types (positions, perspectives, performances, pedagogies, and praxes) their respective story frames (threading, webbing, weaving, growing, and braiding)

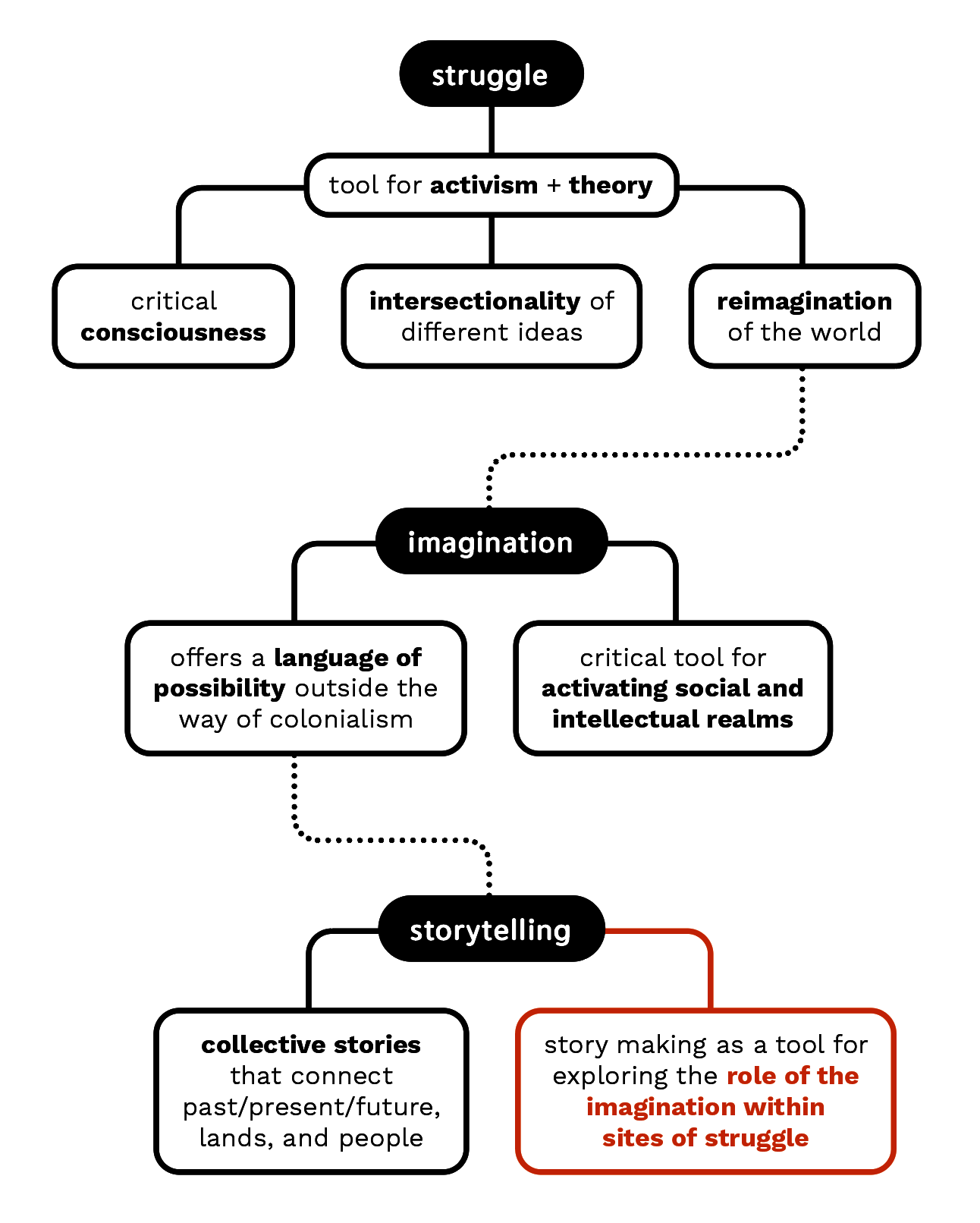

Struggle, Imagination, and Storytelling

Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s (Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Porou, Māori) conceptualization of struggle, imagination, and storytelling serve important roles in situating this work (2012). According to Smith, struggle exists as a tool for activism and theory as it has the potential to enable oppressed groups to embrace and mobilize agency. In sites of struggle, group collective agency takes priority over individual consciousness, and in this sense, it serves as a way to make sense of power relations, agency, and social change. According to Smith, there are five dimensions of struggle: developing critical consciousness, reimagining the world, understanding the intersections of different ideas, offering space for counter-hegemonic movements, and unpacking the structure of imperialism and power. The first three are of more importance to this thesis work, especially the role of imagination.

Further in her work, Smith describes imagination as a social, intellectual, and creative activity that serves a critical role within political projects as decolonization must offer a language of possibility outside that of colonialism. Through engaging with the imagination can oppressed groups (re-)claim the narratives that position them in solidarity with each other and against colonial systems. It is through stories that this thesis work engages the imagination within sites of struggle.

To contextualize storytelling, Smith details 25 Indigenous projects. Exploring all 25 is outside the scope of this work; however, the concepts of testimonio, remembering, connecting, representing, envisioning, reframing, networking, naming, creating, and sharing are still relevant. Refocusing on storytelling as a methodology, Smith incites the importance of collective stories that connect the past, present, and future; land(s); and peoples(s). Further emphasis is placed on the relationship between storyteller and listener, as it is within these reciprocal communicative acts that stories allow for pedagogical witnessing and remembering.

Necessary to mention are Jo-Ann Archibald’s principles of Indigenous Storywork (ISW). Archibald (Stó:lō and St’at’imc), also known as Q’um Q’um Xiiem, details 7 principles: respect, responsibility, reverence, reciprocity, holism, interrelatedness, and synergy (2008). In all senses, ISW is a methodology for engaging the heart, mind, body, and spirit -- which is articulated in the grounding question of this thesis.

Practicing respect requires valuing the people who own and share their stories. Responsibility calls for staying accountable for any mistakes that happen as those sharing stories speak them with great care. Reverence is upheld through active listening and venerating storytellers and their stories. Reciprocity emphasizes the importance of giving back to the people sharing, including sharing the learnings of research. Holism is about seeing the intersections of the intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and physical realms that constitute a whole person. Interrelatedness expands the notion of holism by evaluating the relationships between stories, storytellers, and story listeners. Lastly, synergy is about the power that flows between tellers and listeners within the spaces where stories are shared. Listing these principles serves as an important marker of gauging the appropriateness of the approach to storytelling; therefore, it was vital to hold these close to heart, mind, body, and spirit within every space stories were engaged with.

Image

Diagram detailing the nuances of struggle, imagination, and struggle within the scope of this thesis work.

Deep Learning and Disrupting Cognitive Imperialism

Through the story frames themselves and the content explored in them does this thesis work acquire value. The synergy between content and frame serve to create space for deep learning and disruption of cognitive imperialism imposed by Euro-Western thought.

Celia Haig-Brown (non-Indigenous Euro-Canadian) describes deep learning as a way for a person to transform one’s worldview through extended periods of engagement with new knowledge -- specifically with Indigenous knowledge (2010). Tentatively, this thesis work creates space for deep learning by offering ways of unlearning through embodied storytelling and framing. Through these frames can we holistically engage our stories with Indigenous perspectives of the world.

Regarding the frames themselves, each offers a unique technique for engaging with visual, verbal, and visceral stories that expand beyond the page into physical space. They allow us to more deeply embody these stories by requiring a level of enskilment in crafting them. Additionally, experiencing them requires a level of attention that prioritizes non-linearity and multi-sensoriality -- for example, when weaving performances one must physically enter the space of (e)motions. In this activation of holistic storytelling of the mind, body, heart, and soul do these story frames create diverse spaces for deep learning.

Marie Battiste (Mi’kmaw) notes a need to disrupt the cognitive imperialism maintained by Euro-Western thought -- especially in its universalization of colonial dominance in academia (2005). To do so, Indigenous knowledge must be appropriately centered in ways that allow us to immerse ourselves in new systems of meaning without the distorting lens of Eurocentrism. By centering Indigenous and decolonial approaches in the content of the stories explored, this thesis work serves to disrupt the cognitive imperialism that exists within story-making in academia.

Disrupting this imperialism through stories of pedagogies, positions, perspectives, performances, and praxes demands a level of commitment to centering Indigenous and decolonial principles. Furthermore, the embodiment required from the frames further integrates the learnings from these explorations. Hence, disrupting cognitive imperialism through storytelling becomes an act of decolonizing our minds, bodies, hearts, and spirits simultaneously through attentive story making and diligent story framing.

Image

Diagram detailing the nuances of deep learning and disrupting cognitive imperialism within the scope of this work.

The Story Frames

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles