Image

Sierra Gideon

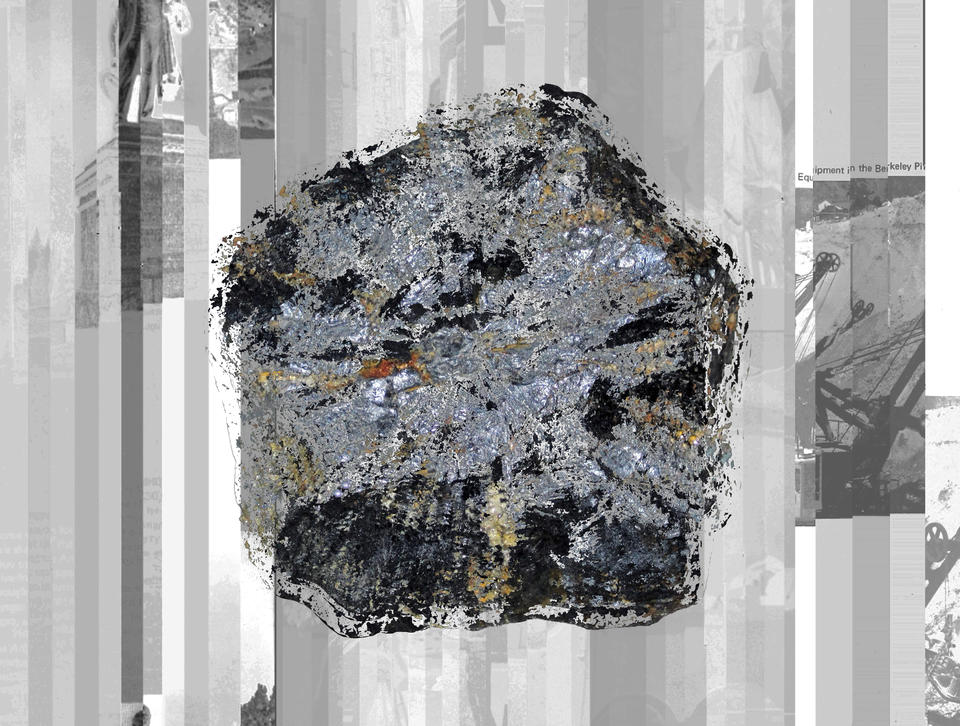

Copper Afterlives: Memory, Image, and Waste in the Postindustrial Landscape of Butte, Montana

Copper Afterlives studies ghostly pasts of open-pit copper mining in Butte, Montana from the mid-twentieth century through the present. In examining spatial reconfigurations—including mass extraction, industrial discard, historic preservation, and landscape remediation—I decenter extractivist paradigms that normalize physical, bureaucratic, and representational violence. While copper materially symbolizes national progress and technological innovation, its extraction from rural peripheries has been achieved at a great cost—as White settlers forcibly removed Indigenous people including the Séliš and Qlispé from mineral-abundant regions; as corporations offset their debts through off-shore operations; and as industrial technologies wrest ore from the earth at an ever-intensifying speed and scale. In the context of public-private management of extractive zones, neither critical representation nor ethical remediation of abandoned mines are guaranteed. It is therefore imperative to critically unravel dominant narratives and extractive visual cultures of open-pit copper mining in Butte so that stories of care, reciprocity, and multispecies agency can emerge.

Image

"The Anaconda Connection" Mural in Downtown Butte

DSLR photograph

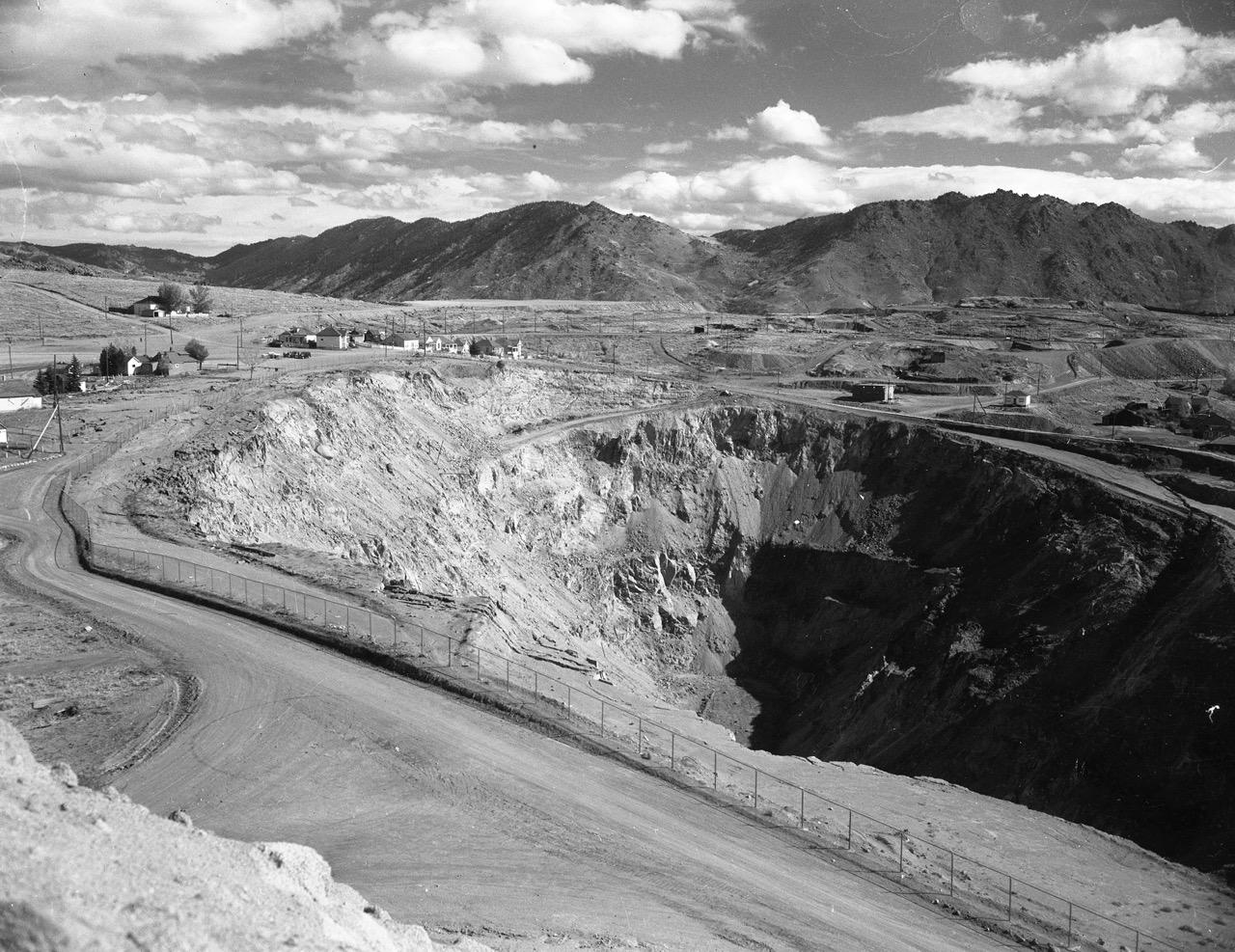

Butte, Montana is not a ghost town, but there is something ghostly about the place, evident in voids carved out of the hillside, in mounds of rock with too low an ore percentage to meet the smelter, and in patches of young aspens growing through blighted soil. Haunted are the headframes dotting the city, the foundations of homes razed in the name of More Copper, the walls bearing traces of subsidence. Silver Bow Creek knows all too well the ghosts of mining past.

One particularly visible ghost is the Berkeley Pit. The former open-pit copper mine flooded with groundwater after ARCO turned off the underground pumps in 1982. Rising groundwater mixed with residual minerals to form a highly-acidic lake. Officials assured the public that the water level would rise over the span of decades, but within a few years, the water rose to a critical threshold.

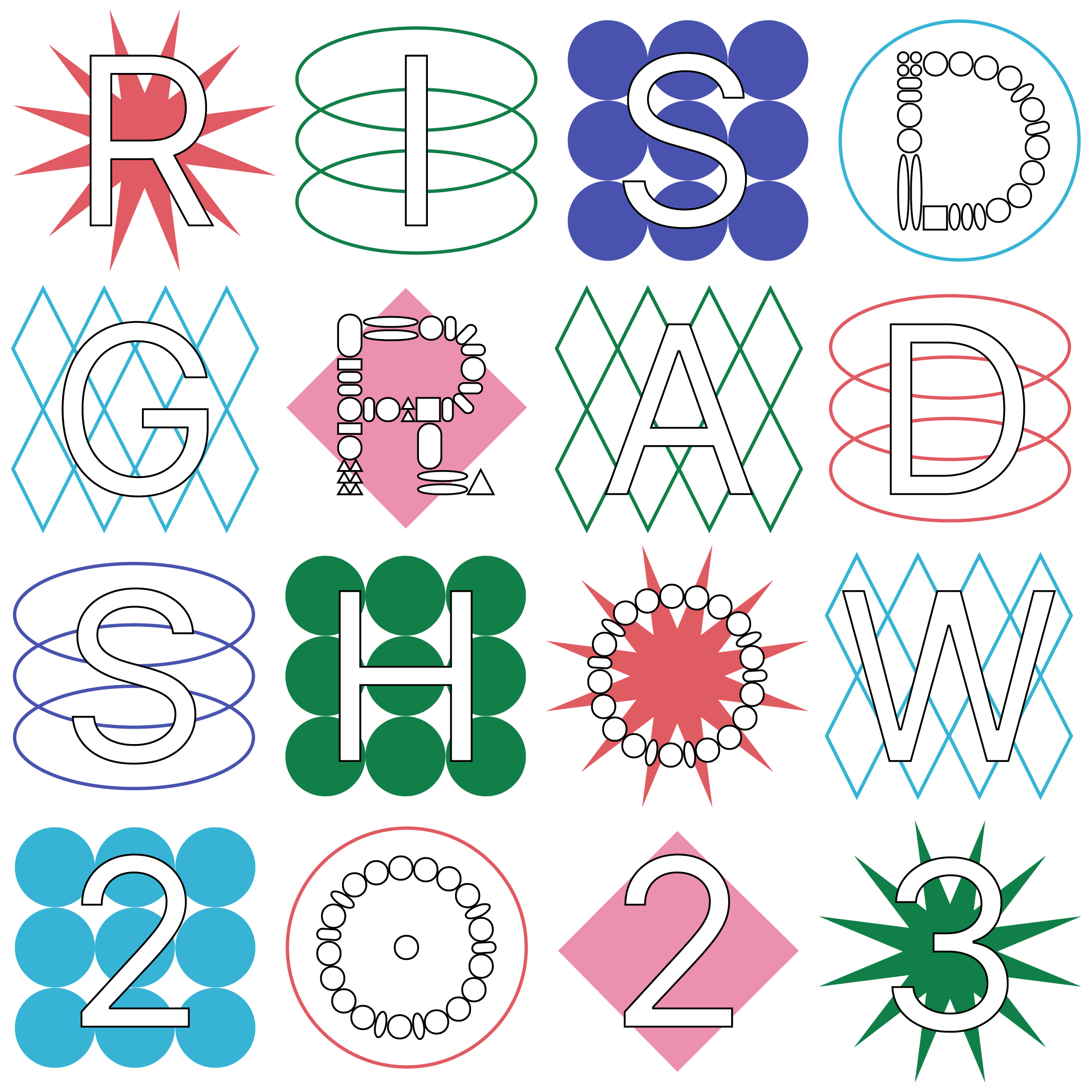

Image

The Mountain Con, One Century Apart

Archival film photograph from the Anaconda Company Mining Company Photograph Collection, used with permission from Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives (left); DSLR photograph (right)1927;

2022

In Centerville and Finn Town, workers’ houses stand as shabby and proud survivors of open-pit expansion. In other places, only the concrete foundations of houses remain. Though the postindustrial landscape of Butte defies categorization as “ruined,” it is no stranger to transformation across spatial, temporal, and material scales. The asphalt path of the BA&P Hill Trail weaves through the Centerville in the same configuration as the former BA&P Railway, the "LARGEST BUT SHORTEST RAILROAD" which once carted tons of crushed ore 26 miles from the Butte mines to the Washoe Smelter in Anaconda.

As I wandered along the reconfigured route, I paused at sites where remnants of the copper industry have been preserved as relics within the Copperway Heritage Park. The BA&P Hill Trail, functioning within a larger network, offers not only a physical space to recreate but a representational space upon which various stakeholders project a public-facing historical narrative.

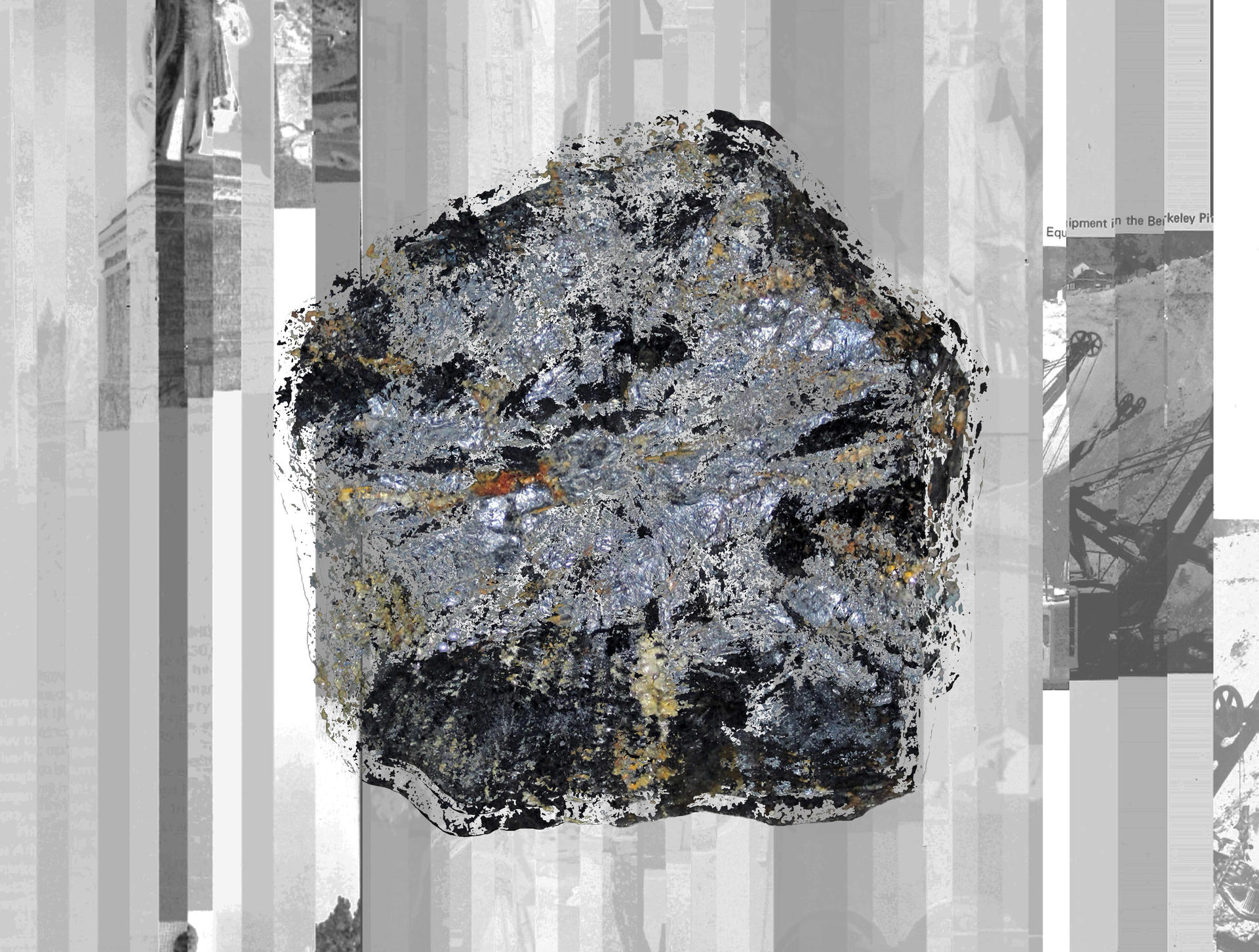

Image

“Alice Pit North of Walkerville,” C. Owen Smithers, October 1960

1960

Political geographer Martín Arboleda writes that mines function as nodes within a global network of extraction rather than as singular, isolated extractive zones. In the context of the fourth machine age, innovations in mining technologies not only resulted from neoliberal compressions of space and time but materialized through the socioeconomic and political marginalization of mineral-abundant, working-class communities in the Global South.

Technology has the potential to liberate marginalized workers from manual labor and precarity, but guarded by corporate stakeholders, the liberatory potential of technology only preserves hegemonic power structures. Capitalist modes of extraction and production link communities across the planet who are marginalized through those very fluctuations of capital.

Image

Pumps Releasing Pit Water into the Tailings Pond

DSLR photograph

Flood at the Berkeley Pit is both natural and technological, but the origin of the threat that the flood imposes to the more-than-human ecosystem is systemic. Here, a semiotic differentiation of the event emerges. For some, the flood represents failure, toxicity, and threat. For others, the event represents necessity, efficiency, and solution to a threat.

The flood, a material consequence of “progress” in the wake of extraction, is kept at bay and mediated in public representations by the same actors that created the potential for the flood. Mediating the virtual threat, for the partially-responsible parties, seeks to conceal the very real threats which have actualized as a consequence of open-pit mining and flooding.

Image

Aspen and Wild Rose in Centerville

DSLR photograph

2022

Ethical remediation in the wake of extraction is not guaranteed. Even after the remedial stages of mitigation are complete and Superfund ceases to be a descriptor for the landscape, the afterlives of mass copper extraction will remain buried under limestone and dirt, contained inside upland waste facilities, and layered in the built environment.

To go uphill, upstream; to look underwater, underground; to shed illusions about the pure, the pristine, and the efficient requires an intentional defamiliarization of once-familiar landscapes. The hillside is a hybrid landscape—a rambunctious garden—to cherish and connect with even as it is forever altered.

1. Re(media)tion

2. Washoe Slag

3.Violet-Green Swallow and Reflections at the Berkeley Pit

4. Camper in Cloud Country

5. Lost Town

DSLR photograph

![A note taped inside of a bar window that reads, "Lost town, [down is crossed out] up here in Butte. History was here. We're tearing it down. God damn, what are we? What are we other than our history? Butte, Butte, I love you. We're here." The blinds inside the bar window are shuttered.](/sites/default/files/styles/half/public/2023-05/NCSS_SierraGideon_10.jpeg?itok=OPgsnYaQ)