Victor Rivera-Diaz

The Aesthetics of the Mexican Public Garden and its Photographic Compositions (1912-1982)

In Mexico, there are currently several collections of photographs which depict the history and development of public gardens and ecological corridors under the management of the National Institute of Anthropology and History. By focusing on two exemplary collections—the Nacho López Collection and Vicente Luengas Collection—I apply a visual studies approach to the photographic archive in order to formulate the Mexican public garden as a branching set of aesthetic (sub-)categories, all of which take into account the creation of garden landscapes vis-à-vis land use policies and historical accounts during the rise of Mexican modernity. In so doing, the primary sub-categories of the Mexican public garden, namely the everyday garden and the stately garden, are intended to elucidate the shifting degrees of publicness rendered visible from the years 1912 to 1982, or the end of the Porfiriato to the final decade of the Mexican Miracle years. Crucially, I view these photographic compositions through the Nahuatl poetic and epistemological tradition known as in xochitl in cuicatl (“flower-and-song”); i.e., the photographs showcase the alignment of the evocative (flower) and the variable (song). I conclude that public gardens were visually, territorially, and aesthetically activated through diverging modes of viewing in order to openly resist or, conversely, advance ironclad regimes of government.

Concerning the aesthetic expression of gardens, the commonplace appearance of their vegetal qualities would, at first glance, not be subject to historical constructions in their encounter with the documentary photograph. One might consider words used to describe the commonplace, such as ‘garden-variety,’ in order to bring to mind a sense of their general inconsequentiality in the broader photographic landscape. In order to problematize these presuppositions, it is important to consider the under-examined banality or garden-variety appearance of gardens in light of their ecological implications, which make them a terrain of subdued contestation in the Anthropocene. It is precisely in the garden’s encounter with the enterprise of aesthetics—which comprises differences in judgment and attitudes—that a world-making project of negotiation emerges in what the aesthetician Yuriko Saito refers to as the “aesthetic dimensions of everyday life.” Crucially, this negotiation between the material and the visual is not only subject to the historically constructive prism of the documentary: it is actively composed by the documentary as seen from the observer’s perspective of the photograph. Therefore, this aesthetics research is based on the following premise: photography, in its strive towards true representation to unify the evocative (flower) and the variable (song), can simultaneously document and compose an aesthetic tradition across the arc of time.

Image

Fuente de sodas en un jardín público de Macuspana, 1982. Photograph by Nacho López. Colección Nacho López, Fototeca Nacional, INAH. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Image

Jardín de una casa en unidad habitacional (c. 1960-1964). Photograph by Nacho López. Colección Nacho López, Fototeca Nacional, INAH. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Two distinct aesthetic sub-categories of the everyday garden are of fundamental interest: the collective garden and the incorporated garden. Beginning with the collective garden, I define it as a public garden that is either a stand-alone site or, conversely, a belted site contained within larger mixed-used areas such as plazas and parks; and which is marked by the aesthetic experience of expansiveness. Moreover, I define the incorporated garden as a public garden which is subject to governmental oversight in denoting institutional publicness and its ties to homogeneity, nationalism, and symmetry, all of which lend themselves to an aesthetic experience of reticulation.

Image

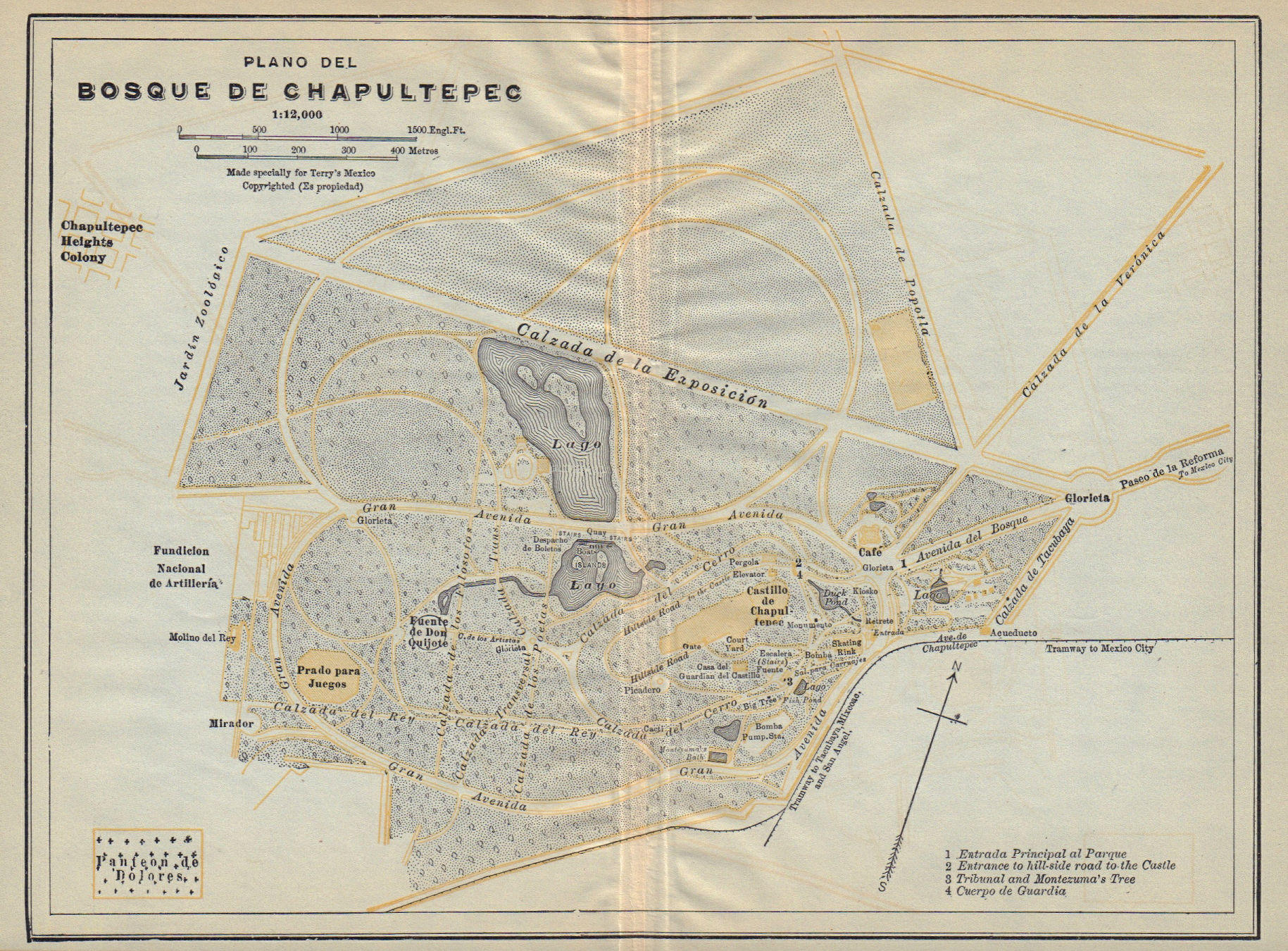

Plano del Bosque de Chapultepec, 1933. Map by Phillip T. Terry. Antigua Print Gallery. Public domain.

With regard to the stately garden, the totality represented in the selected photographs operates at the scale of the urban landscape. A special attention is placed on the divergences in land use that are made visually apparent along the more salient human-constructed boundaries contained in the image, such as a rock wall or a fence around the perimeter of a metropolitan park, and in what might be described as a negotiation of space. Concerning the establishment of public gardens, these spatial negotiations provide for two additional sub-categories that I identify as being subsumed within the heretofore discussed stately garden. These are: (1) the model garden, and (2) the bound garden.

I define the model garden as a public garden which is modeled after a broader series of international and domestic design influences, and is intended to promote a state-sponsored aesthetic experience of a tamed natural landscape. Relatedly, I define the bound garden as a public garden which has been historically produced and documented by the state in terms of its perimetrical boundaries; and which are, in form and effect, bound by law as the aesthetic experience.

It is beyond a photographic shadow of a doubt that the historical instatement of Mexican modernity during the final decade of the Porfiriato, and its subsequent ideological perpetuation during the height of the Mexican Miracle years, are visually composed across both the Vicente Luengas Collection and the Nacho López Collection. Moreover, it is evident that these two collections are opposed such that their respective modes of viewing are mutually exclusive of each other. On this point, Nacho López’s photographic gaze can be said to look outward towards the fruits of the everyday. Conversely, Vicente Luengas’ compilatory gaze looks reflexively towards the modernizing objectives of the Porfiriato. Regarding the everyday garden, the aesthetic of expansiveness witnessed in the collective garden stands in contrast with the aesthetic of reticulation in the incorporated garden, both of which maintain a measured sensibility to the landscape through the prism of the quotidian. In addition, the everyday garden as a whole is visually and onto-epistemically counter-posed to the stately garden, that is, the witnessing of the model garden aesthetic mobilizes nature while, relatedly, the bound garden aesthetic totalizes nature; this is done through the prism of the Porfirian beau ideal of hygiene.

All things considered, the rendering of the gardens’ physical features (flower) in each of these photographs are simultaneously aligned with the differing modes of viewing (song), such that the photographic composition of the Mexican public garden rests upon shifting soils of publicness in the archive of Mexican modernity. Thinking beyond the Nacho López Collection and the Vicente Luengas Collection collections, it would appear that the garden landscape, precisely through its garden-variety illusion, is a contested domain of terra firme proportions.