Masking

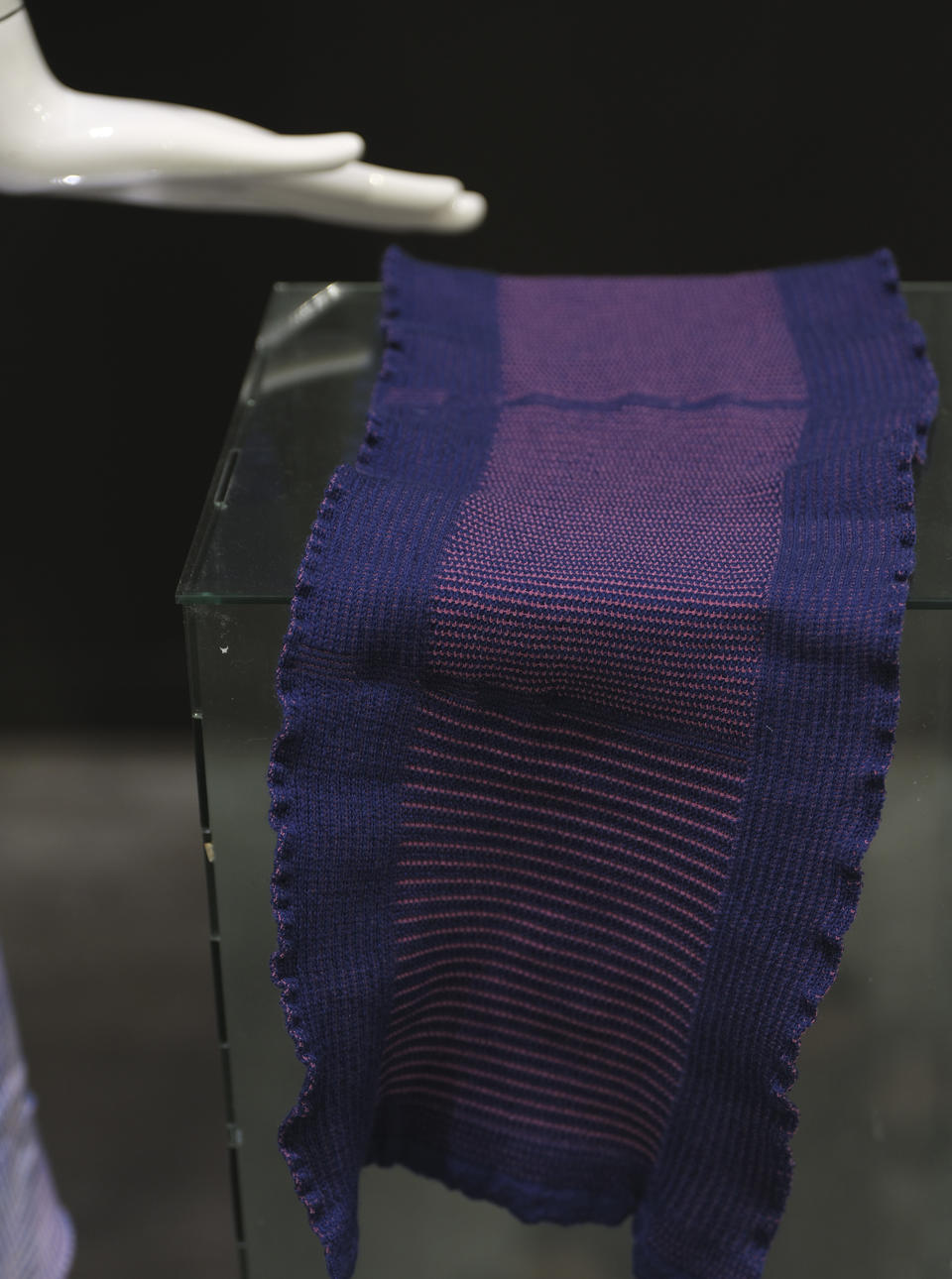

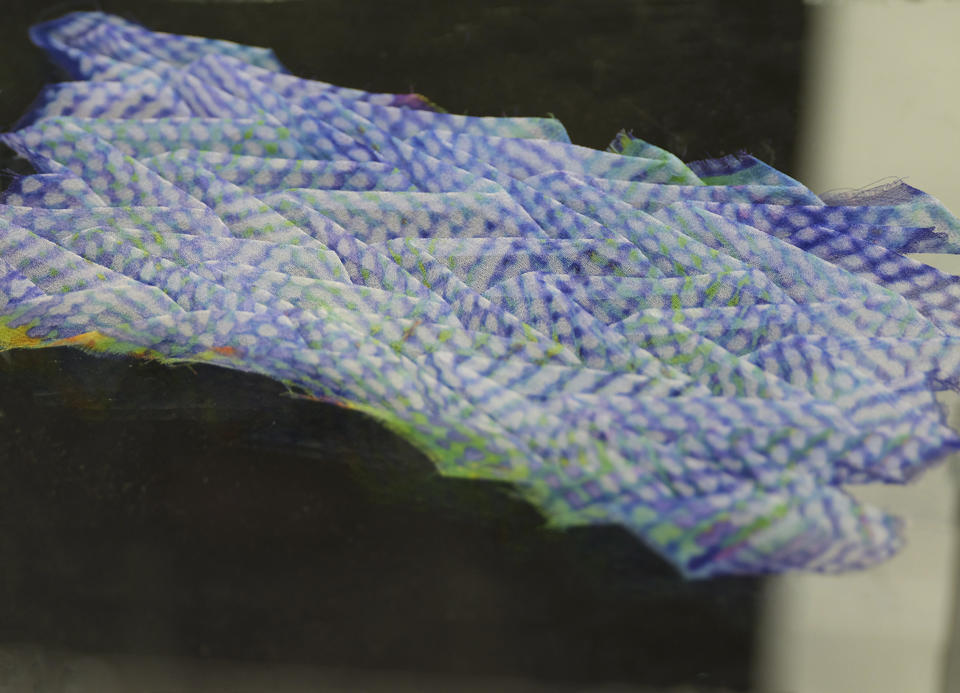

I was 21 years old when I found out that I would need to manage another chronic disability for the rest of my life. Until this point, I had spent my days navigating my way through Autism (and ADHD, although unknowingly). I had this hope that as an adult, with a lifetime of effort, I would be uninhibited by my disabilities. I wanted to put to rest all the agonizing strife they brought me. I dreamt of an ‘normal life’. As doctor after doctor was unable to give me a clear answer, I watched my dream slip through my fingers like dust. I was overwhelmed with a persistent mental fatigue, and I soon found myself in pharmacies purchasing canes and braces. The medical devices I now relied on for support became constant reminders of what once was. Carrying my Fibromyalgia diagnosis around in the form of awkward medical wear was unbearable, and my new reality threatened to break me. I felt I would never be free.

As a by-product of my experiences in special education, it had always been my ultimate goal to appear ‘normal’, no matter what it cost my health. I refused to let slip any emotional fits, physical ticks, or attention deficits. My face would turn red before I ever cried from the chronic pain. I imagined myself as a ‘functional’ disabled person and with a concrete willpower, I contained myself emotionally and physically – nothing seemed to bother me. I did not complain.

This is known as masking; the act of hiding or suppressing symptoms of health conditions, usually in situations or environments where individuals are expected to act in socially normative ways. I now ask – by whose standards? Like the way an ill-fitting garment harasses the wearer, masking steals from the body. If we must strip other parts of ourselves to find support, can we truly feel whole?