Image

ARTIST ON ART

Riva Lehrer

Riva Lehrer

American, b. 1958

66 Degrees, 2019

Acrylic on paper

25.4 x 35.5 cm. (10 x 14 in.)

Courtesy Zolla Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, and the artist

Photograph by Tom Van Eynde

I am a portrait artist. Trying, anyway. Like all of us, my life has been spun around by COVID.

In March 2020 the pandemic shut my studio down. For decades, my portrait collaborators have come to the privacy of my home studio and participated in intense, profound live sittings. I believe that the true product of a portrait is not the object, but the exchanges between artist and collaborator. Intimacy is the very foundation of what we do. I am who I am because of the countless transformative conversations I have had in the studio.

But—suddenly—would I ever be able to sit with another person facing me from the other side of the easel?

After several panicky months, I developed methods that allowed me to persist. I began by doing portraits over Zoom, drawing my collaborators framed in the rectangle of my laptop screen. There were good conversations, but not quite what happens when we are together; just the slightest bit less fluid and honest. I struggled with the simplified, flattened view afforded by the MacBook.

—

Just before the world became alien, I had been in discussions with Rosemarie Garland-Thomson about sitting for a painting. Garland-Thomson is one of the foundational scholars and theorists in the field of disability studies. We’ve known each other for twenty years; she has been a support and a mentor since the beginning. Her work on the phenomena of staring influenced my thinking about the links between portraiture and public/private scrutiny of the variant bodymind).

Rosemarie committed to come to Chicago in the spring and begin the process of sitting. But then came the plastic shields and the masks and the loss of faces everywhere.

Arranging a remote photoshoot became our only option. I’d have to try to art-direct over Zoom. I found a wonderful photographer, Crystal Gwyn, who is based in San Francisco near where Rosemarie lives. The session took hours; I was grateful that we were also assisted by Rosemarie’s husband, an architect with a great eye.

The process of choosing a portrait narrative isn’t easy, and for people who experience stigma, it can be pretty fraught. I hated having to work from photos; they’re such distortions of reality and utterly void of intimacy. My collaborators determine the narratives that represent who they are. I try to give them control over how they are depicted.

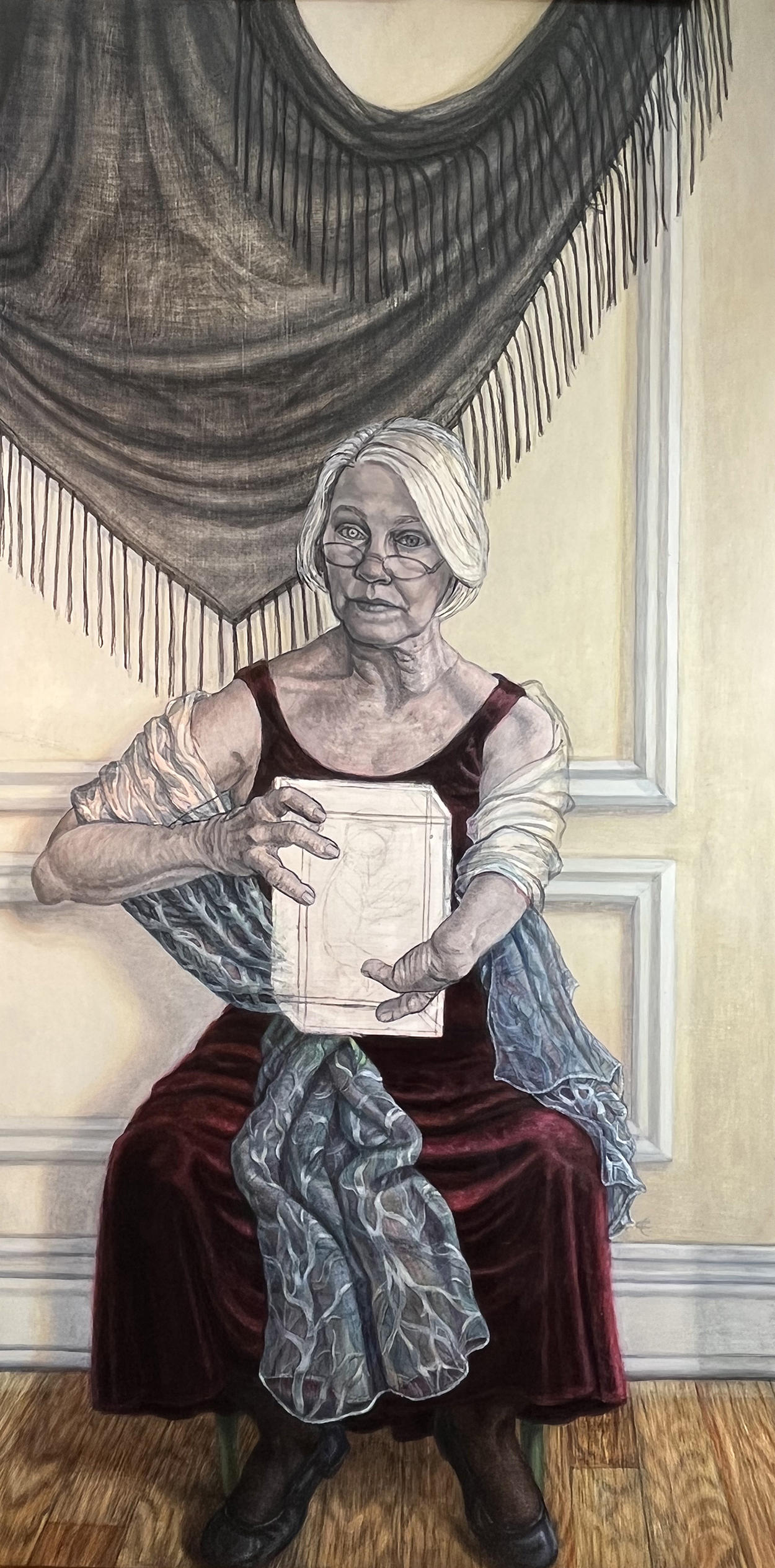

Rosemarie was quite definite about how she wanted to be seen. (I include a shot of the unfinished piece, though I have never published a work-in-progress before.) Rosemarie and I had long discussed what it’s like to live in a nonnormative body. Our constant experience of being stared at and judged.

In her portrait, Rosemarie holds a medical vitrine containing a fetus. The fetus will have the same asymmetrical arms and hands as she. The painting is composed as an hourglass, with the vitrine as the crux. Portrait as alpha and omega of the self; a natal body that defines the life to come.

I sent her some progress shots so she could see how it’s going. In a pair of texts, she replied:

I’m so moved by this. I don’t recognize it as me, but that’s the point of the portrait. That’s really important. I really want to explain about the misrecognition business. You are wonderful.

Image

Riva Lehrer

American, b. 1958

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, in progress

Acrylic on wood

121.9 x 60.9 cm. (48 x 24 in.)

Courtesy of the artist

I didn’t know what she meant. The resemblance was fairly good, though of course it will be stronger—and much more nuanced—when complete.

Later, she explained what she meant by describing an intense site of mis/recognition: times when she is surrounded by mirrors in a department-store dressing room. These mirrors force her to see her body and arms in a way that she never in life sees her own body. Rosemarie recognizes this confronting of one’s own appearance as seen by others as a classic scene of women in literature, film, and art:

For someone with a disability that has such an unusual appearance, when you never see anyone else who looks like you, it is hard to imagine how you look like to other people. The people I see in my life almost all have the same kinds of arms and hands. I don’t see my own arms and hands in the way that others see them except when I look in the mirror or at photographs of myself. In other words, I seldom have the opportunity to see myself as others see me. And so, in some sense, my imagined self has the same arms and hands as everyone else. When I say I misrecognize myself in your picture of me, what I mean is that I don’t see myself the way you portray me.

Rosemarie further explained she avoids looking at her own hands, intentionally not seeing them. I imagine that her mental picture lays a kind of blur over where her hands would be. Rosemarie habitually drapes herself in lovely scarves and shawls that partially cloak her arms. This is why I chose the slightly brooding black shawl on the wall, and the slipping blue scarf she wears—yet is not concealed by.

So when I sent her the photo of the portrait in progress, it neither matched her mental image nor the pictures she has typically allowed to be made. She poses in ways that hide her hands in photographs other people have made of her. She says that allowing her hands to be out there, naked, as the center of this portrait is both frightening and thrilling. A picture, she says, of the truth of her body.

Rosemarie elaborated further:

So the work of the picture, as a portrait of a person with a disability, is not just to show the truth of my unusual body but to tell the story of why people with disabilities hide themselves away from the world, why wheelchair users have covered their legs with blankets, why prosthetics used to look like flesh, why blind people wear sunglasses, why chemotherapy patients wear wigs and hats. This portrait recognizes the fundamental truth of many disabled bodies and their experience of misrecognizing themselves in a world full of people who don’t look like them.

This is why I make portraits. For my collaborators, the world offers stigma. My studio is a site of defiance.

—

Image

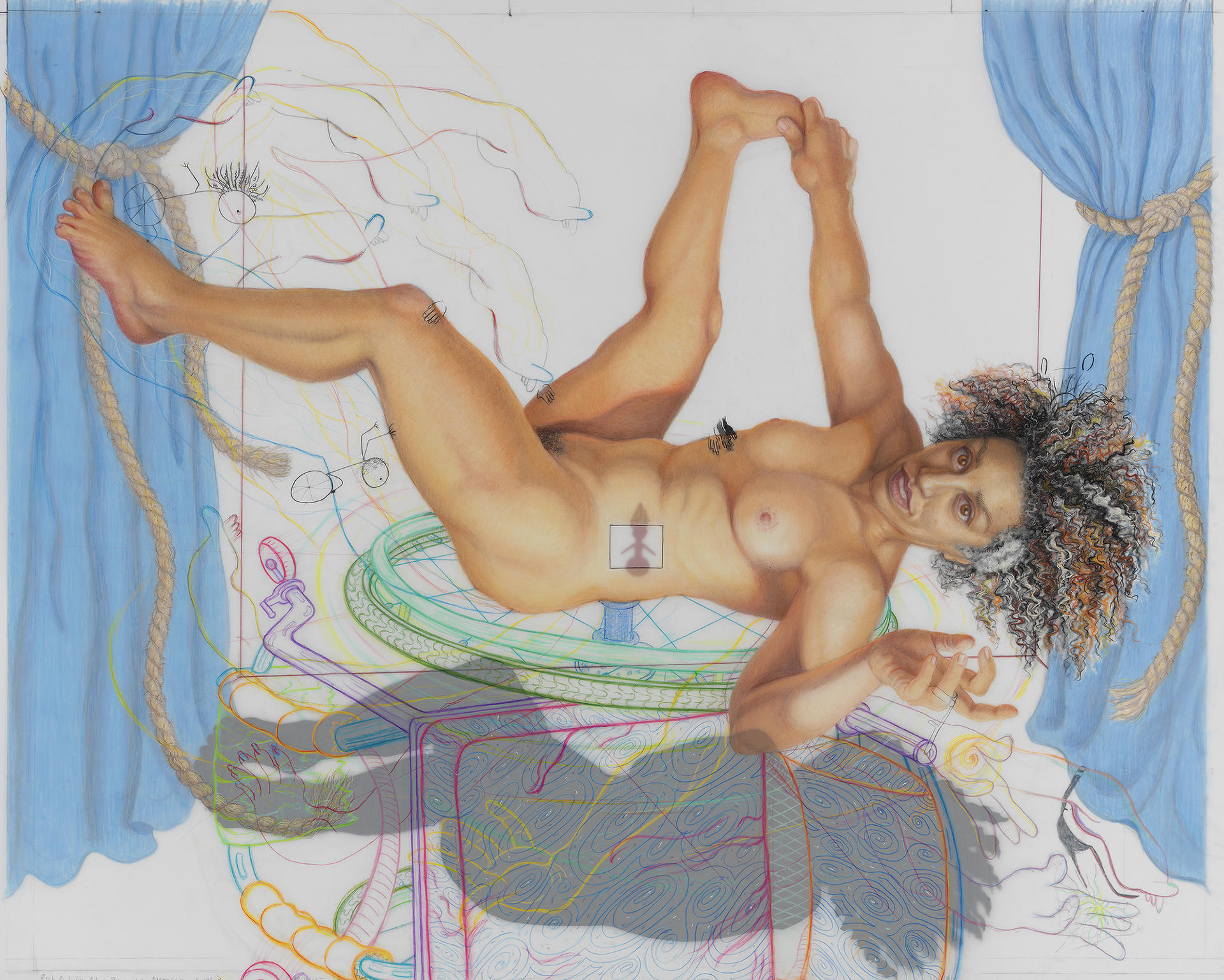

Riva Lehrer

American, b. 1958

Alice Sheppard, 2016

Two layers of Mylar acetate with mixed media and collage

101.6 x 120.7 x 5.1 cm. (40 x 47 1/2 x 2 in.)

Courtesy Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, the collection of Larry Gerber, and the artist

Photograph by Tom Van Eynde

This form of misrecognition, as it happens, is a well-known phenomenon. Studies have shown that when we approach a mirror (or sit before a camera) we do a fair amount of unconscious composition, in addition to intentional arrangement. The composed reflection is an expression of how we think we look our best. We may intentionally leave out—unsee—the parts of ourselves we find unacceptable. For women, in particular, the mirror is a well-established site of self-critique in which we compare ourselves with the parameters of acceptable appearance (and try, too often, to meet the beauty standards of the day). Psychological studies also say that looking too long in the mirror can even engender hallucinations, causing one to see monsters, strangers, aliens.

Mirror-gazing has its hazards.

—

When I give book talks these days (my memoir, Golem Girl, came out in 2020) I often end with an exercise for the audience. I ask them to find two photos on their phones that were taken of them by someone else: one picture that they love, and one they hate but have nevertheless kept. I ask what makes one pleasurable and the other unacceptable. The unacceptable images tend to be described as “ugly” or “weird” or “didn’t look like them.” Most often, that’s because the subject was caught unaware, did not self-compose, and was presented by a view incongruous with their self-schema.

When we are confronted by a reflection that violates our parameters, this may prompt a defense in the form of misrecognition. An uncanny self: the you / not you that disorders self-conception. A picture can make the most intimate thing we own—our bodies—unfamiliar and disconcerting.

Even ordinary photos can be startling: remember, what we see in the mirror is the reverse of what everyone else sees. For me, my hair parts to the left; for everyone else, it falls to the right.

And yet, each audience member has kept both images. It strikes me that together, these comprise the history of figuration. The “acceptable” photo is understood as a self-portrait, while the “disturbing” picture is converted to something like a figure painting. It was kept as the depiction of an event: a wedding, a party, a holiday dinner with family. That photo becomes a story, wherein the subject is just an actor in the tale. Almost invisible to themselves as they subsume into the narrative.

I began making self-portraits many years ago. I was trying to make myself familiar to myself. For much of my life I had avoided looking in mirrors, even to the point of taking off my (very thick) glasses when I walked around so I wouldn’t spy my reflection in random shop windows. This became increasingly insupportable. I only endured because I became invited into the world of disability culture. This offered me a radical re-comprehension of my experiences, and it engendered the desire to understand my own body. I needed to comprehend what people saw when they looked at me. Self-portraits (e.g., 66 Degrees) have helped me to—literally—incorporate myself into myself.

Not that that work is ever settled. I still have a hard time watching footage of myself walking around or being seen from the back. Some things will always pull the old shame in their wake.

But it comforts me to know that we all can become strange to ourselves. And a reminder to me that sometimes my collaborators step into my studio and fall to the uncanny valley, alone.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.