Image

Masami Teraoka 寺岡 政美

b. 1936 in Onomichi, Japan; works and lives in the US

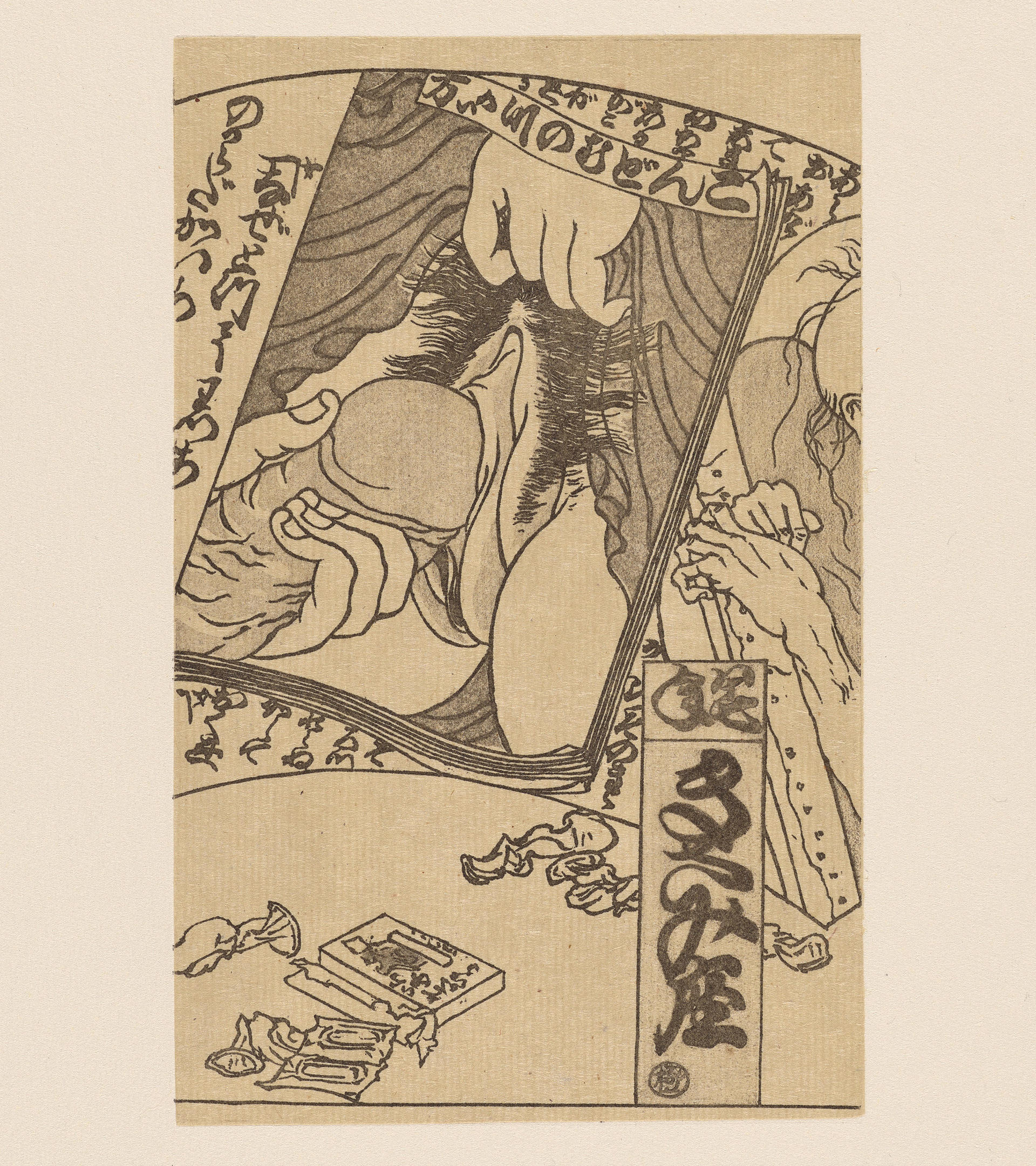

Condom Pillow Book, from the AIDS Series, 1987

Lift-ground etching, aquatint, and soft-ground

counterproof chine collé on kitakata paper

Image: 17.6 x 11.3 cm. (6 15/16 x 4 7/16 in.)

Gift of Evelyn Lincoln 2021.18.2.2

© Masami Teraoka

Joey Terrill

—

AIDS Series—one work but multiple views—a double take, twenty-six years apart and both versions by me.

These prints evoke Japanese woodblock traditions that began in the seventeenth century. It’s a trope Teraoka has used since the 1970s to provide a wry commentary on the clash of Eastern and Western values, poking fun at both American consumerism and its disruption of Japanese traditions. But this work from 1987 takes that same stylized ukiyo-e tradition in a very different direction. Here, the pathos of the geisha’s story plays out in front of us, pulling at our emotions. No humor. Upon seeing the geisha’s vacant eyes warily regarding her suitors, I found myself sharing her unspoken anxiety in trying to forestall the inevitable, as it’s too late for a condom. In ’89 I was thirty-four years old and had just tested positive for HIV. The prognosis at that time was I had about a year to go before developing AIDS. It was hard to fathom any future.

The geisha was going to die, and so was I. Unopened condom packages are strewn about her as she drapes herself over the balcony, her suitor’s fingers exploring her. (I wondered if she had been tested.) Her stare is distant, indicating to me that she was seeing her own mortality, anticipating the physical withering away that comes with end-stage AIDS. Those bony fingers of her client on the right side of Condom Pillow Book would one day soon become her own. I had seen this happen to beautiful loved ones around me. Her physical deterioration will stand in sharp contrast to the elements of natural beauty found in the “floating world” illustrations of ukiyo-e. I’ve seen that contrast in my own world. Her natural beauty will be gone. The dexterity required for her calligraphy and playing the shamisen—gone! Her gifts for conversation, dancing, and reciting poetry—gone! Falling victim to neurological deficits related to any number of opportunistic infections, her ability to make art—gone! In those spare wisps of ink that define her eyes, I saw all of that.

With this work, Teraoka removes the scourge of AIDS as centered in the gay male community (my world) and places it in an Eastern cultural art tradition free from Western / Judeo-Christian roots. I was a Westerner observing a geisha and I saw my internal self reflected. Looking at her filled me with sadness.

The 2015 exhibit Art AIDS America included a painting from this same series—Tale of 1000 Condoms / Geisha and Skeleton. Like visiting an old friend, I smiled upon seeing a familiar image that hadn’t changed. I had changed. Living with HIV for thirty-five years, surviving clinical trials, side effects, and politics, making art while simultaneously grieving for those who died, I was now “undetectable.” I was no longer the geisha. For me, she symbolized the millions of girls and women globally who have succumbed—and continue to succumb—to AIDS.

For me, engaging with this sublime work of art in such a deeply personal way is a priceless gift.

Image

Image

Masami Teraoka 寺岡 政美

b. 1936 in Onomichi, Japan; works and lives in the US

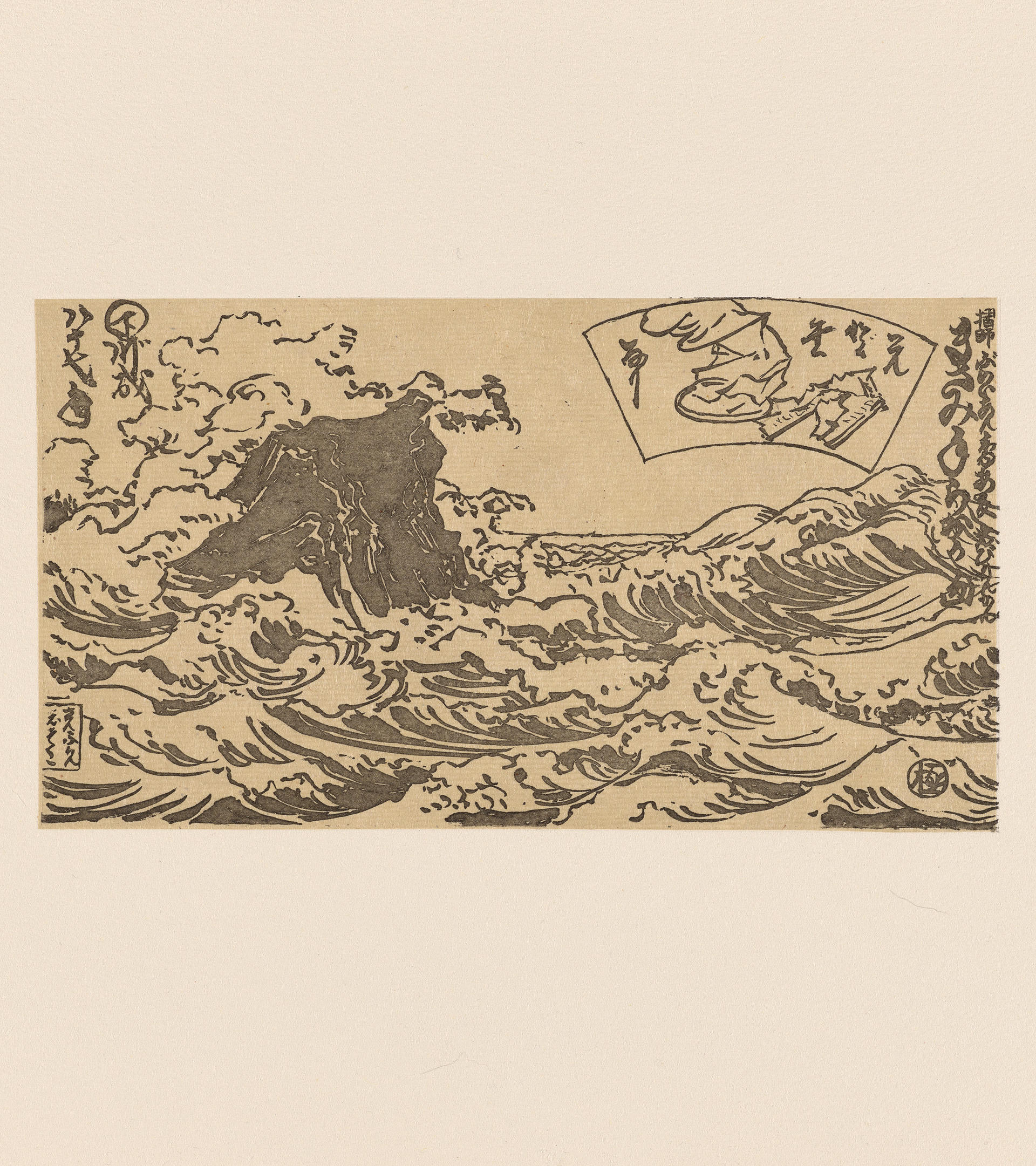

Waves, from the AIDS Series, 1988

Lift-ground etching, aquatint, and soft-ground

counterproof chine collé on kitakata

backed with German etching paper

Image: 12.7 x 22.9 cm. (5 x 9 in.)

Gift of Evelyn Lincoln 2021.18.2.5

© Masami Teraoka

Cynthia Wu

—

Masami Teraoka’s AIDS Series, like many of his other works, alludes to Japanese woodcut printmaking in its visual style. In this set of black-and-white ink panels, entitled Waves, Geisha and Gaijin, Woman at Balcony, Condom Pillow Book, and Artist and Canvas, nipples are hungrily devoured by mustachioed mouths, fingers and penises are inserted into vaginas, latex barriers such as a diaphragm and condoms (packaged, unwrapped, unrolled, and discarded) are neatly placed, clasped in hands, or strewn about. Teraoka’s self-portrait appears in the final panel, self-reflexively portraying a wizened man in front of a canvas. Calligraphy fills the spaces around the figures and objects. As in the bulk of Teraoka’s other works, the AIDS Series images render indistinct the boundaries between one body and another and one object and another. Even the panels suggest a delineation of the images across each. Whether it is between individual humans, between the human and the nonhuman, or between organic and inorganic matter, the blurring of multiple forms of being is front and center. Everything leaches and morphs together into a dynamic mass.

The HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ’90s blurred entities and categories. The virus that causes HIV disease, like all viruses, is neither alive nor not-alive. The virus reveals the body’s porosities as multiple bodies interface with one another. Any body (or anybody) can become both receiver and transmitter. The ubiquitous condoms that grace the landscape of Teraoka’s AIDS Series suggest, on the one hand, their dogged distribution by public-health proponents and, on the other hand, the futility of believing they will be used unfailingly. Meanwhile, the first panel, which shows a large ocean wave cresting and an inset at the upper right depicting a used condom, makes us wonder how much of this refuse makes its way into our seas.

A news article in 2021 reported that more than a billion face masks have entered the ocean since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. These castoffs have become floating plastic waste, their mass measuring about seven percent of the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Still, the number of masks in the ocean is, overall, only a tiny percentage of the single-use masks that have been manufactured since the start of the pandemic, and all will have to be disposed of somehow1. The two pandemics the United States has bungled its response to—first HIV/AIDS and now COVID-19—are marking our natural environment in indelible ways. More broadly, COVID-19 has been a sobering wakeup call to intervene in our present relationships with the environment. The effects of large-scale meat production, unsustainable fishing, petroleum extraction, carbon emissions, deforestation, and other harms show us—like Teraoka’s images—there is no sealed-off barrier between one body and another, one mass and another. It all winds up inside us.

Image

- Bevan Hurley, “1.6 Billion Disposable Masks Entered the Ocean in 2020 and Will Take 450 Years to Biodegrade,” Independent, July 31, 2021, https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/masks-ocean-covid-pla….

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.