Image

DOUBLE TAKE

Faience Sistrum

Gina Borromeo / Wai Yee Chiong

Egyptian

Ritual Rattle (Sistrum), 664–525 BCE Glassy faience

Height: 19 cm. (7 1⁄2 in.)

Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund 1995.050

Image

Image

Gina Borromeo

—

Finely made of an apple-green glassy material, this object looks like a sculpture. How could it be a rattle? Where would you hold it? What sound would it make?

It is, more precisely, a sistrum (from the Greek word seistron, meaning “that which is shaken”), a percussion instrument most often associated with ancient Egypt. A handle, now missing, originally extended vertically from the bottom. Looking at the piece in profile reveals three holes on each side; movable rods holding metal disks would have been inserted through these holes. The Egyptian word for this type of sistrum is sesheshet; the spoken word mimics the rustling sound these objects make when shaken. Usually made of bronze or wood, sistra were shaken by priestesses during religious ceremonies and dances honoring certain goddesses such as Hathor—the goddess of music, happiness, and celebrations depicted on the base of this sistrum. Made of a ceramic material known as Egyptian faience, this was probably a ritual or votive object associated with a pharaoh. Pharaohs were sometimes depicted holding sistra, and some faience sistra handles are inscribed with names of pharaohs.

Long locks of hair frame Hathor’s face. She wears a broad collar, a type of necklace worn by both men and women in ancient Egypt. Above her head is an open shrine (naos) with a row of rearing cobras (uraei)—symbols of divine power and protection. The larger uraeus in the shrine’s doorway signifies the sun god Re, father of Hathor, and might recount the myth of an angry Hathor transforming herself into the eye of Re and attempting, without success, to destroy mankind. Goddess of fertility and motherhood and the protector of the ruler, Hathor was a deity who had to be appeased.

Cows and bulls were widely venerated in Egyptian culture, and several Egyptian goddesses were associated with cows, but none more so than Hathor, whose earthly manifestation was a cow. The triangular face and elongated ears in this depiction hint at her bovine nature. Egyptian gods were also represented as falcons, ibises, lions, and cats, and deities of the sky, earth, rivers, mountains, and cities often appeared in human form. Still others were hybrid in form, possessing the head of a human and the body of an animal or vice-versa. The head was the primary, essential element of the god, with the body describing the secondary aspect. Rare is the Egyptian deity who was represented in human, animal, and hybrid forms, but this was true of Hathor.

Hathor was also known as the mistress of faience, a material the Egyptians called tjehnet, meaning that which is scintillating and brilliant, like the light of the sun, moon, and stars. This representation, in form and material, thus embodies several of Hathor’s many roles: cow goddess; daughter of the sun god, Re; a potentially vengeful deity who must be pacified; protector of rulers; patron of joy, music, and celebrations; goddess of the sky; and mistress of faience.

Image

Wai Yee Chiong

—

The elongated ears on this carved rattle of the Egyptian goddess Hathor allude to the deity’s association with the cow. The importance of bovines within the ancient Egyptian belief system recalls the sacredness and significance of cattle in many Asian cultures.

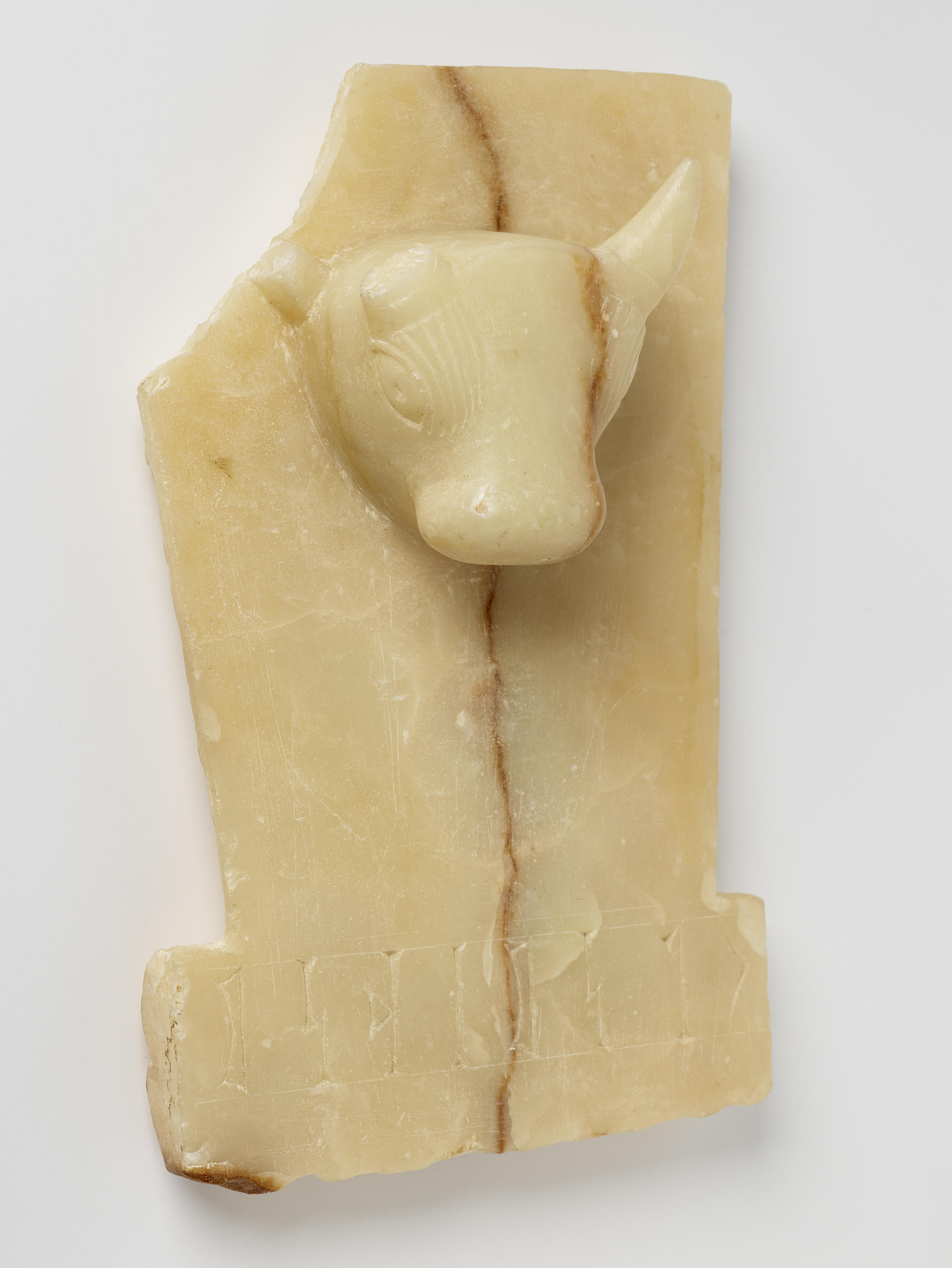

On the Arabian Peninsula, the people of the ancient Qataban kingdom (ca. 400–1 BCE, present-day Yemen) portrayed their moon god, Ilumqah (or Almaqah), as a bull. High-relief alabaster carvings of bull heads dating to as early as the first century BCE are commonly found on funerary steles from this region. An inscription on the base of such a stele in the RISD Museum (1) names the patron who dedicated the sculpture. It was believed that by inscribing their name on a stele, the worshipper would be eternally connected to that deity. Emerging from a flat plane, the bull’s finely articulated eyes and muzzle add to its expressiveness.

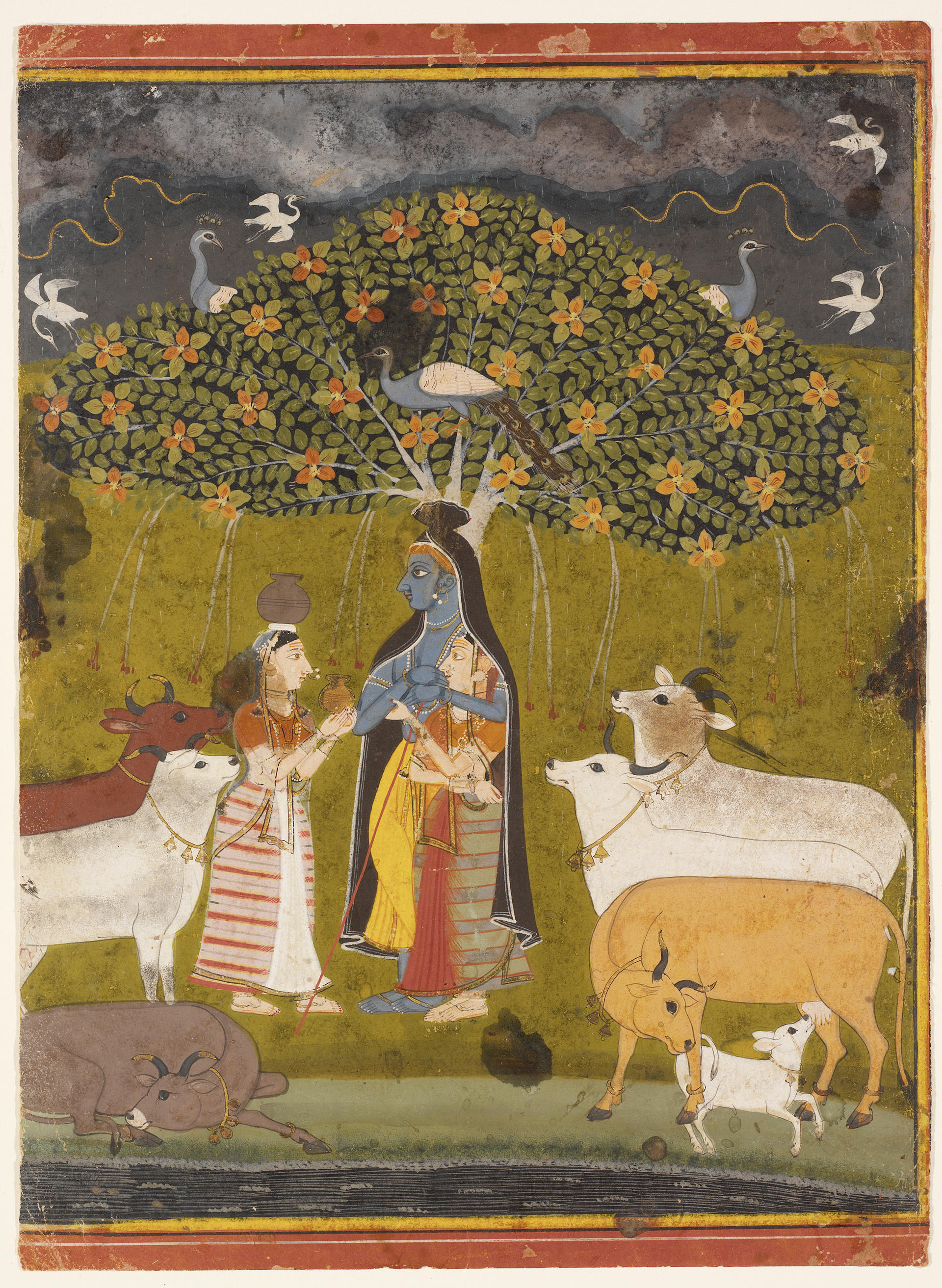

On the Indian subcontinent, Hindus have for more than three thousand years considered bovines sacred, associating them with various deities. Bulls and cows frequently accompany the Hindu deities Shiva and Krishna. Shiva’s sacred mount, the divine bull Nandi, is often featured on carved reliefs outside Shiva’s temples, keeping watch as gatekeeper and protector (2). Cows are also beloved by and frequently pictured with the god Krishna (3), who was known as the cowherd. During religious festivals such as the Govardhan Puja, when devotees celebrate Krishna, cows are not only decorated for the occasion, but cow dung is piled into heaps and adorned with flowers to symbolize Mount Govardhan. Such practices indicate that every part of the bovine was considered sacred. In fact, cow slaughter is legally prohibited in numerous states in India, and Hindu practitioners do not eat beef.

In China, the strong, hardworking ox, fundamental for farming, is also symbolic on many levels, appearing as one of the twelve zodiac animals and a star in the Chinese constellation. From as early as the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), earthenware oxen figurines have accompanied the dead in tombs, ensuring them a prosperous and abundant afterlife. For Buddhist practitioners, pictures of ox herding serve as guides for meditation and a metaphor for the path to enlightenment. Conceived in the 1300s, these images narrate the relationship between an ox herder and his ox, beginning with distrust and hostility, eventually leading to peaceful coexistence, and finally resulting in enlightenment.

I turn again to Hathor and marvel at how many civilizations and cultures, regardless of where and when they existed, have created belief systems based on divine bovines. In ancient Egypt, Hathor was a provider and a potentially vengeful force. In today’s era of industrial farming, cattle—important sources of food and material—have significantly destabilized the environment, reminding us that human actions can potentially provoke the vengeful nature of cow deities.

Image

(1)

Yemen (Qataban Kingdom)

Stele with Bull’s Head,

ca. 400–1 BCE

Alabaster (calcite)

22.2 × 35.6 cm. (8 ¾ × 14 in.)

Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund 84.150

Image

(2)

India

Shiva and Parvati, 1000s–1100s

Sandstone

64.0 × 41.0 × 25.5 cm. (25 3⁄16 ×

16 ⅛ × 10 1⁄16 in.)

Corporation Membership Fund 63.049

Image

(3)

India

Krishna and Rahda in a

Rainstorm, ca. 1690

Opaque watercolor on paper

25.4 × 18.4 cm. (10 × 7 ¼ in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 42.268

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.