OBJECT LESSON

Meaningful Pasts

Stewarded into the Present:

It’s Up to Us

Sháńdíín Brown

Image

FIG. 1

Diné (Navajo) artist once known

Necklace, ca. 1930s

Silver, turquoise, and cotton twine

Anonymous gift 55.050

When I first started working at the RISD Museum in June 2021, this Diné silver squash-blossom necklace [Fig. 1] caught my eye.1 As a Diné asdzáán (Navajo woman) from a family of jewelry makers, I am enthralled with Diné jewelry. This example stood out to me not only because of its numerous blue and green turquoise stones and intricate stamp work, but also its historical and cultural meanings.

Image

FIG. 2

Diné (Navajo) artist once known

Necklace (back side), ca. 1930s

Silver, turquoise, and cotton twine

Anonymous gift 55.050

This necklace came into the RISD Museum collection in 1955 through an anonymous donor. The museum records tell us that it is Diné in origin and not much else. This lack of information is not unusual for Native American objects collected by the RISD Museum before the late twentieth century. Working with the Native American and Indigenous collections here, I have quite a few times encountered a historic work with little provenance information and asked the object, “How did you get so far from home?”

Sometimes the museum records tell a story of how the piece ended up at the museum and sometimes—like with this necklace—they do not. The donor did not provide the museum with the name of the maker or makers, the date the necklace was made, or the place it was made. The lack of attribution, date, and geographical origin is not uncommon for historic Native American objects in museum collections across the country, especially if the work was made for the tourist trade, as I suspect this necklace was.

When this piece was gifted to the museum in 1955, Native American art was typically perceived by non-Native audiences as folk art or craft instead of fine art. There was little or no emphasis on the individual who made the piece, but rather a focus on their tribe or Native American and “Indian” identity. While I do not have a lot of information about the work, I know that the necklace is both beautiful and technically advanced, especially considering that the maker did not have modern silversmithing tools. It is also an example of Diné artisans’ cultural history of innovation, skill, and self-reliance.

Image

FIG. 3

Carl Moon (1878–1948), The Silversmith, 1907–1914.

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution N31720.

Image

FIG. 4

Crystal Littleben (silversmith and Miss Navajo Nation 2017–2018) wearing a squash-blossom necklace underneath her Miss Navajo sash. Photo courtesy of Crystal Littleben.

*

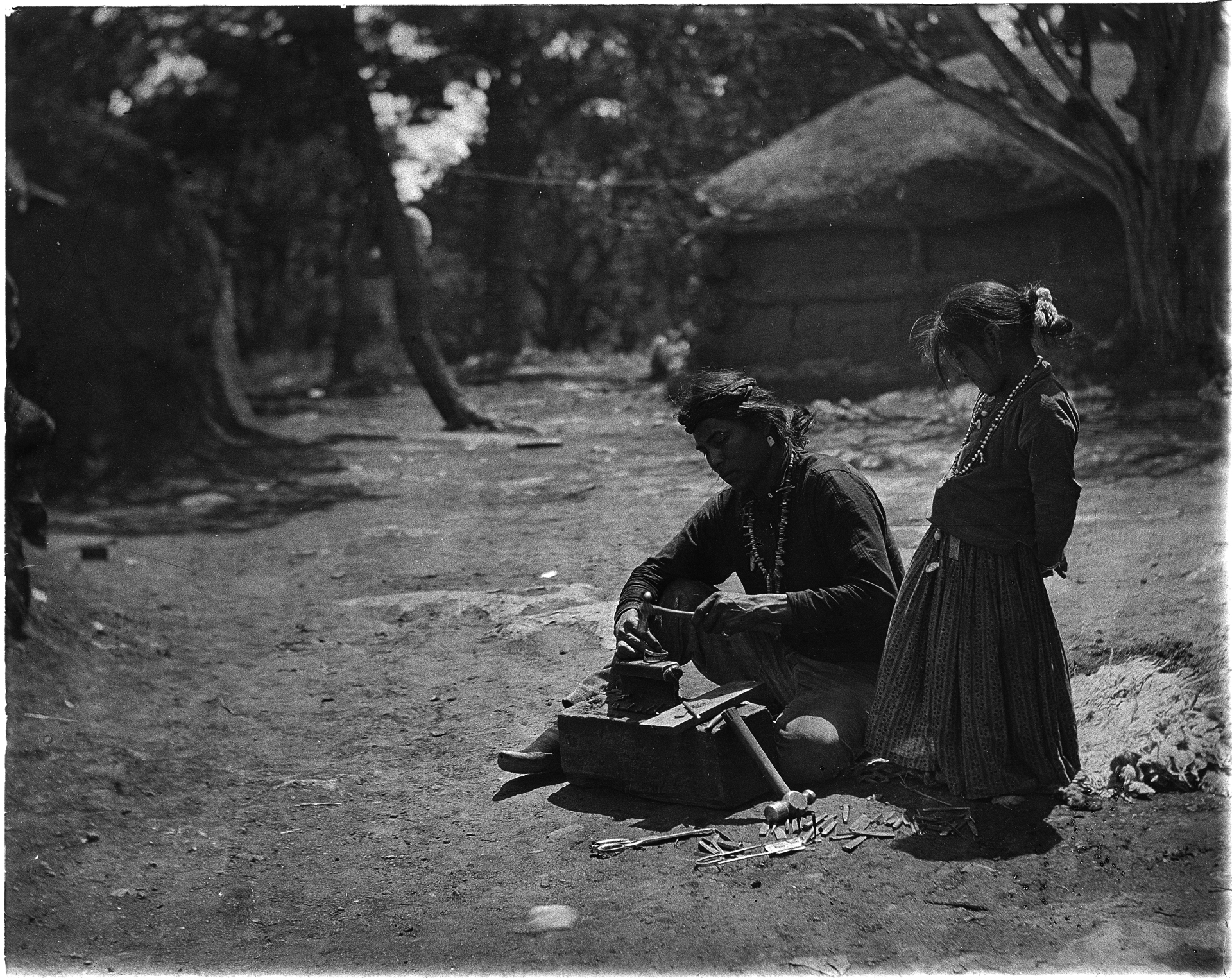

Scholars do not know exactly when Diné started silversmithing.2 While it is not an ancient craft, it is a core art form in Diné culture today. Atsidii Sání (Old Smith, ca. 1830–1918), often credited as the first Diné metalsmith, learned blacksmithing from Mexican metalsmith Nakai Tsosi (Thin Mexican) and began silversmithing sometime in the 1850s, before the Navajo Long Walk.3 The Navajo Long Walk occurred in 1864, when the US federal government forced more than ten thousand Diné to walk hundreds of miles from Diné Bikéyah (Navajo homelands) to Hwéeldi (place of suffering), or Fort Sumner, in eastern New Mexico.4

Federal Indian assimilation policies ran rampant in the 1800s, and Diné were imprisoned at Fort Sumner with the expectation that they embrace aspects of American culture like farming, Christianity, and the English language. In 1868, when Diné leaders signed the Treaty of Bosque Redondo with the United States, the Diné were freed under treaty stipulations. After they returned home, silversmithing became more popular as tribal members taught each other the craft.5 Additionally, after the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, non-Diné-owned trading posts opened across the Navajo Reservation. These trading posts sold food to Diné people and purchased Diné art, such as silverwork, for resale. In 1880, the transcontinental railroad began operating in the Southwest, allowing tourists to travel to the region.6 Hospitality companies such as the Fred Harvey Company advertised the Wild West and a glimpse at Indian lifestyles7 at a time when Americans embraced the Myth of the Vanishing Indian, which posited that Native Americans were doomed to extinction due to white civilization’s ultimate superiority. In fact, the Fred Harvey Company commissioned Carl Moon (1878–1948) to photograph Native American people of the Southwest for marketing purposes. This (most likely staged) photograph shows a Diné silversmith (possibly Cli-thlanny Begay) at work on an anvil with his silversmithing tools as a young Diné girl looks on [Fig. 3]. Together, trading posts and tourism companies facilitated the sale of Native American art, such as Diné silverwork, to white Americans visiting the Southwest. By 1900, Diné were nationally recognized for silversmithing.8 The influx of tourists interested in Native American art continued into the early twentieth century with the widespread use of cars.

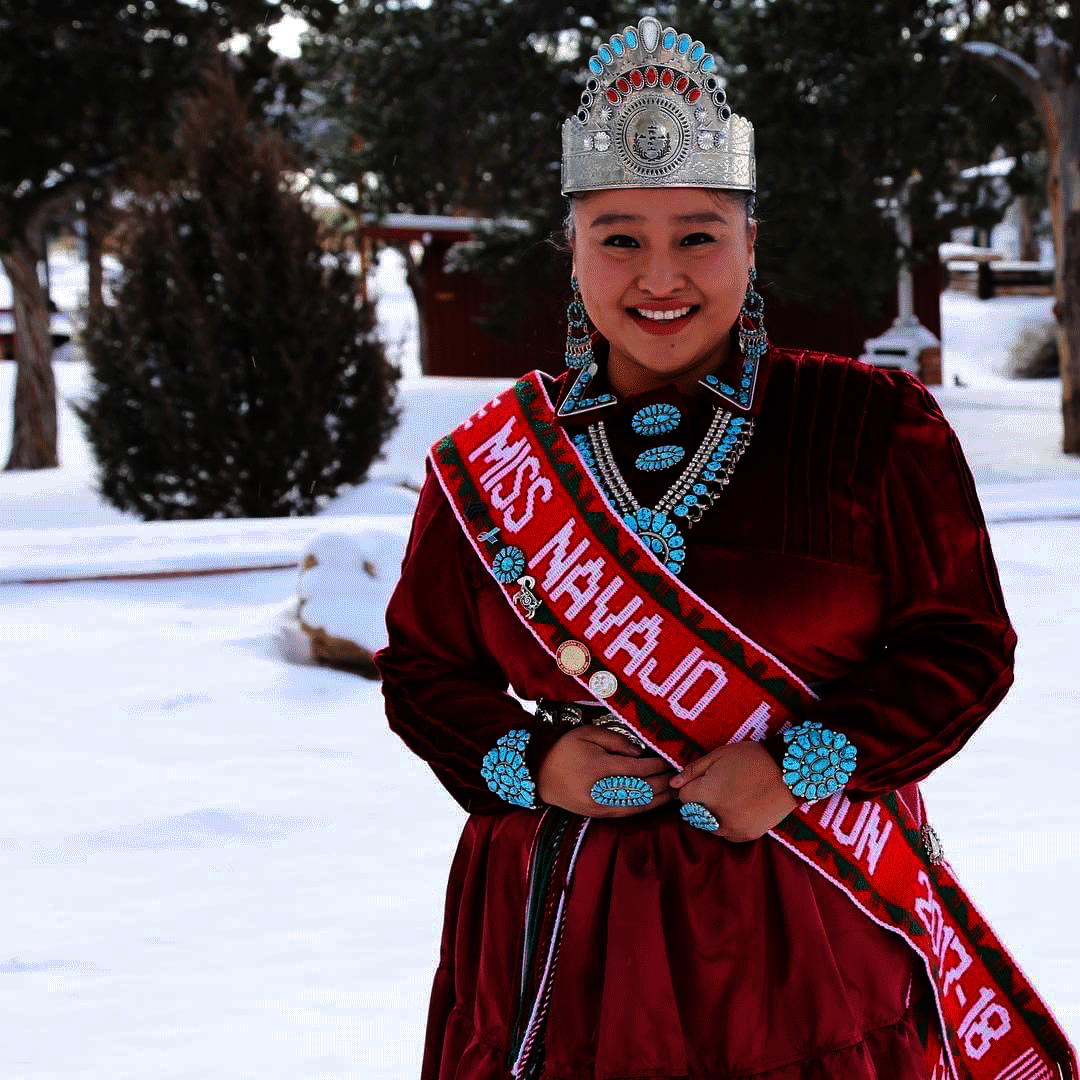

All living cultures, including Diné culture, are constantly evolving, their art practices adapting over time, responding to new materials and techniques and shifts in purpose and aesthetics. When Diné silversmiths began making squash-blossom necklaces in the late nineteenth century, the design was not traditional, but new.9 Today, squash-blossom necklaces are deeply intertwined with Diné culture and a common element within Diné regalia [Fig. 4].

The core elements that make up squash-blossom necklaces include symmetrical design and the use of silver, squash-blossom beads, the crescent-moon pendant, and turquoise. The Diné aesthetic often incorporates symmetry. This can be attributed to the core Diné cultural component hózhó, which roughly translates to “balance, beauty, and harmony.”

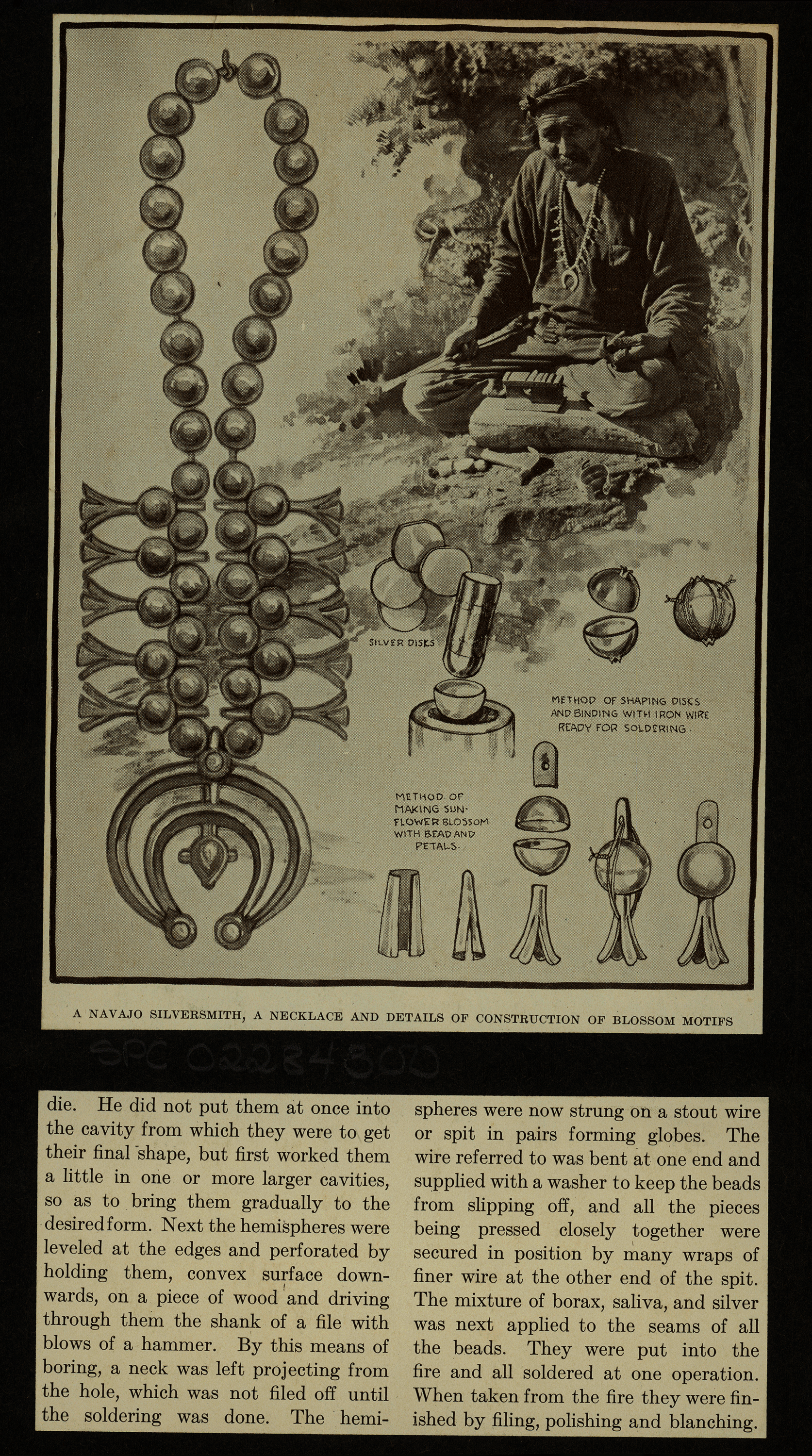

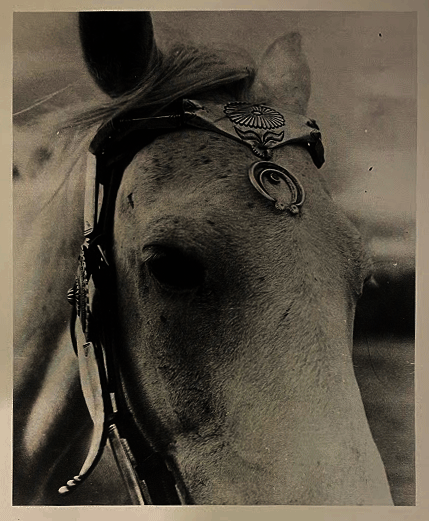

Image

FIG. 5

Silversmith in Native dress with tools, squash-blossom necklace, and details of construction of blossom motifs, ca. 1930. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution NAA INV.02284300.

The earliest source of silver for Diné silversmiths were melted American and Mexican silver coins. Eventually, the United States and Mexican governments outlawed melting coinage, prompting trading post owners to import sheet silver into the Navajo Reservation for Diné smiths to use.10 The most recognizable features of squash-blossom necklaces are their silver squash-blossom shaped beads and crescent-moon shaped pendants. For the beads, Diné silversmiths drew inspiration from the blossoms of a squash plant as well as Mexican and Spanish silver clothing ornaments resembling pomegranates, which have a similar shape.11 The Diné word for this bead is yoo’ nímazí disya gi, which translates to “bead which spreads out.” The circular beads were originally made from hammering silver coins into disks, hammering them upward into globes, and then soldering them together to make round beads. Curled sheet silver was then soldered to the bottom of beads to make the squash-blossom form [Fig. 5]. When designing the crescent-moon shaped pendant, Diné metalsmiths drew inspiration from Spanish, Mexican, and Great Plains tribes’ horse bridles with crescent-shaped ornamentation that rested on the horse’s forehead [Fig. 6].12 Some scholars believe that the Spanish adapted the crescent moon-shaped design of the Moors in North Africa, who placed a version of the Islamic Crescent on their horse bridles.13 The Diné word for the pendant is názhah and translates to "crescent shape." Historically, the názhah was made by carving the crescent shape into a piece of tufa stone (a rock made from volcanic ash) and casting the silver into it.14

Squash-blossom necklaces from the “First-Phase” era of Diné jewelry (1868–1900) did not commonly incorporate set turquoise stones, but later necklaces often do.15 Turquoise is a core material in Diné jewelry. Diné elder Wally Brown explains, “Turquoise is just to let the Holy People know when we are addressing them that we understand our origin, which is of course from the second world, before we came into this world. So when we pray to them and we are wearing our turquoise and our silver, they look at us and they say, ‘There is one of our children that knows where they are from and where they are going, what are they asking for; let’s give it to them.’”16 Tribes in the Southwest frequently traded materials like turquoise with each other.

*

The stones in the RISD Museum example could be blue gem turquoise from Nevada or another turquoise mine in the Southwest. This necklace is most likely entirely handmade, created in either an outdoor studio [Fig. 3] or inside a hogan (a traditional Diné home). The maker hammered the spherical silver beads, also called Navajo pearls, from sheet silver. The squash blossom beads in this necklace differ slightly from the original First-Phase squash blossom bead shapes made entirely of silver, instead comprising of a flat piece of silver set with a hand-cut turquoise stone and three blossom petals facing outwards. Originally, Diné smiths chased silver with an awl to create decorative patterns. Eventually, smiths used files and cold chisels for these details.17 During the 1880s, when smiths began creating and utilizing small iron or steel die stamps, creativity in design soared.18 Die stamps have designs filed into one end that is hammered into the work to reproduce the designs.19 Stamp work is central to Diné silverwork and smiths form a myriad of patterns from curvilinear to geometric. Some Diné smiths pass stamps down from generation to generation, creating family designs.20 For this necklace, a triangular stamp with six serrated lines and a liner stamp were used to hammer the designs into the silver [Fig. 7]. The flat silver of the squash blossom bead has a clam design on each side of the turquoise stone. The triangular stamp was used to border the clam form and the liner stamp was used five or six times within the clam shape. Furthermore, the triangle stamp borders the turquoise. The maker strung the stamped squash blossom beads and Navajo pearls together with cotton twine. In the middle of the necklace is a hand-crafted názhah pendant, also made from sheet silver, with two bands of horizontal and vertical set turquoise. The triangular stamp was used on the silver crescent lines above each band of turquoise of the názhah. Finally, a hand-crafted silver j-clasp secures the work to the wearer’s neck.

I think that this piece was made in the 1930s, before World War II. We know that it was made before 1955, because that was the year it was donated to the museum. Additionally, scratches from a hand file are clearly seen on the turquoise stones [Figs. 7 and 8]. After World War II, Diné silversmiths used machinery to evenly polish the stones. Next, the stones are roughly the same size, but still unique in shape. This indicates that they were hand-cut stones and not the commercially calibrated examples Diné silversmiths used later in the twentieth century. The bezels, or silver settings at the base of the stones, look serrated by a handsaw or file. By the late 1950s, most Diné silversmiths were buying commercially made serrated bezels.21 Lastly, the heavy use of turquoise stones is more closely associated with the 1930s than any earlier decade. Unfortunately, there is no stamp or hallmark attributing a maker or makers, which is common for this era of Diné silversmithing. “PUZU” is scratched into the back of the názhah, which is not a typical Diné name but could be the original buyer’s name [Fig. 2].

I imagine that an intricate necklace like this was a showpiece displayed in the window at a trading post on the Navajo Reservation or in a border town near the reservation, enticing tourists to purchase this work and take it back to wherever they called home. In the 1930s, trading-post owners would supply Diné silversmiths with materials such as sheet silver and wire, then buy the jewelry for resale. Individual artists did not make fair profits for their work and were not properly credited within the trading-post system.22 Trading-post owners also suggested design ideas, pressuring Indigenous makers to create works that looked “Indian.” Squash-blossom necklaces in particular became popular tourist souvenirs.23 During this era, many Diné makers sold their work to the trading posts as a means of survival.

Image

FIG. 6

Silver naja on horse bridle, ca. 1920–1970.

Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), 038930.

Image

FIG. 7

Diné (Navajo) artist once known

Necklace (details), ca. 1930s

Silver, turquoise, and cotton twine

Anonymous gift 55.050

Image

FIG. 8

Diné (Navajo) artist once known

Necklace (details), ca. 1930s

Silver, turquoise, and cotton twine

Anonymous gift 55.050

*

Diné are creative, adaptive, and self-reliant. That deeply rooted spirit of self-reliance is tangibly demonstrated across the centuries through weaving, sand painting, and other mediums. A common saying in Diné culture is t’áá hwó’ ají t’éego, which translates to “it’s up to you.” Diné scholar Andrew Curley writes, “Navajo notions of work and responsibility, the core of t’áá hwó ají t’éego, ‘you are responsible for your own well-being,’ were directly tied to survival and the necessity of providing subsistence for your family largely through physical labor.”24

Our art forms, like silversmithing, became means for survival, especially after Diné society drastically shifted from the subsistence economy that existed before the Navajo Long Walk to a cash economy, which was imposed after the Treaty of Bosque Redondo. Diné silversmiths made art to sell to tourists and provide for their families, using materials that were around them in Dinétah (Navajo homelands), like silver coins and turquoise. With those profits, they bought food, materials, and livestock.

Diné did not have a written language until the 1930s, around the time this necklace was probably made. We told histories orally and through artistic mediums. Interestingly, there is no word for art in the Diné language; this lack of terminology is common throughout Indigenous languages.25 The visual elements in Diné culture are means to express ideas and tell stories within the community. Today there are more than 300,000 citizens enrolled in the Navajo Nation, and cultural meanings are diverse.26 Individual Diné hold different cultural beliefs, and there is not a monolithic of the squash-blossom form throughout the tribe.

When I look at this necklace, I think of balance, strength, and femininity. I remember learning from my family that the squash-blossom necklace design is associated with femininity and fertility. Squash is a traditional Diné food. The squash blossom beads reference this ancient plant’s pollination, in which female and male squash flowers reproduce. The delicate balance of female and male harmony is essential in matriarchal Diné culture. Another interpretation of the design is the form being a metaphor for life. The top bead on the wearer’s right side represents the start of life and each beadreferences subsequent stages of life, with the last bead on the left side indicating the end of our the end of our journey in this world. For some Diné, the názhah represents the womb and/or umbilical cord, hence the close placement to the wearer’s navel.27 The názhah is also interpreted by some as the bow of Nayenezgá (Monster Slayer), one of the Hero Twins in the Diné creation story who rid the world of monsters.28

Arapaho and Seneca beadworker Ken Williams Jr. writes, “Jewelry offers a window into Native peoples’ worlds and reminds us that it was alive then, is alive now, and will be alive for many generations to come. Many heirlooms are passed down among Native families, and we recognize that each piece holds the story of where it originated, how it was made and used, and how it got to its owner.”29 My shimásání (grandmother) gifted me her squash-blossom necklace before she passed away. Her necklace is an heirloom in our family that I cherish and hope to pass on to the next generation.

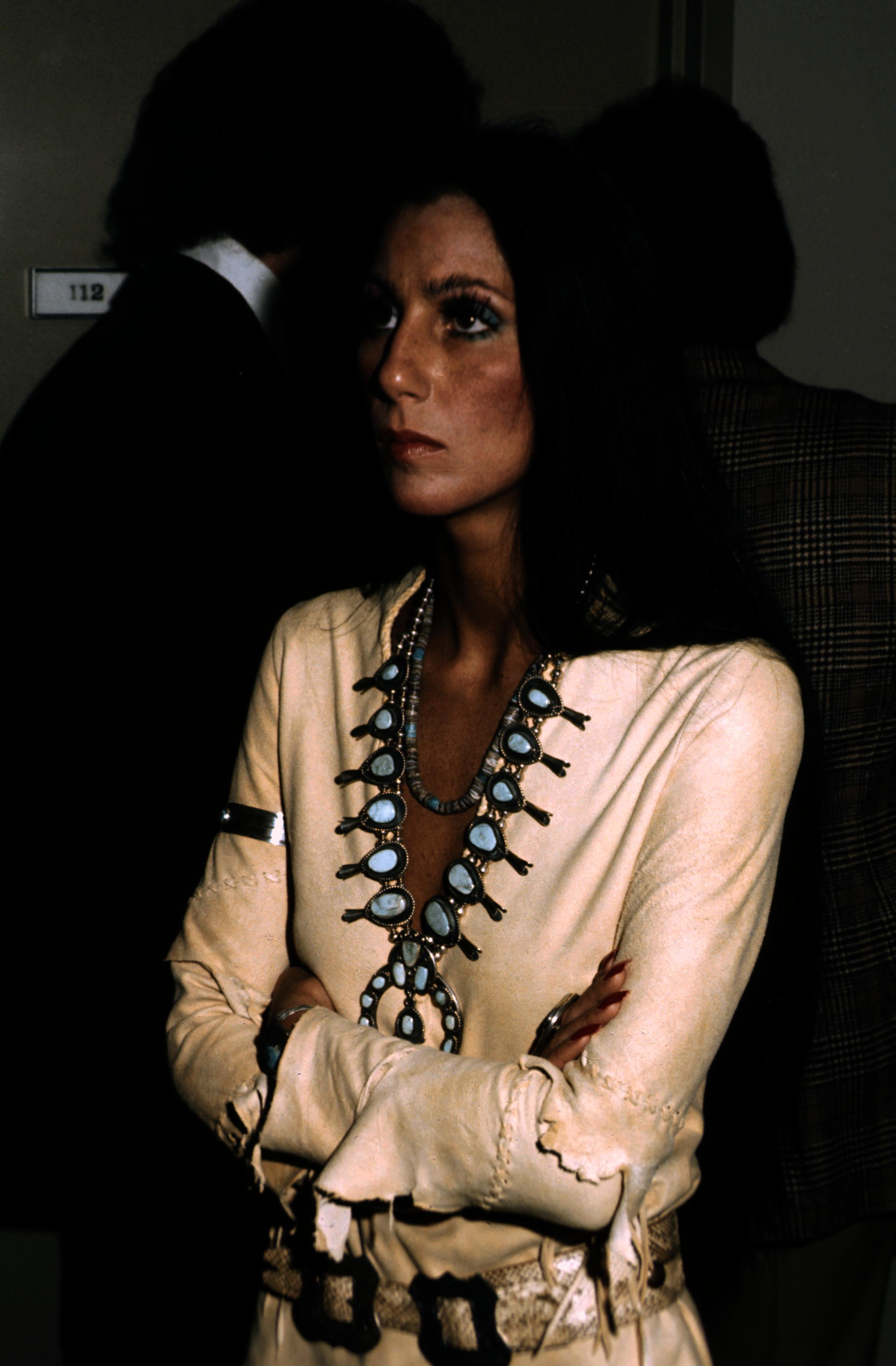

Image

FIG. 9

Cher wearing a squash-blossom necklace, 1974. Courtesy of Michael Ochs Archives / Stringer / Getty Images.

Image

FIG. 10

Nanibaa Beck (Diné), Squash-Blossom Hoops | Rails + Coral,

fabricated sterling silver squash-blossom hoops with coral

and 14k gold accents. Photograph courtesy of Nanibaa Beck.

Image

FIG. 11

Author polishing the squash-blossom necklace.

Squash-blossom necklaces are now an iconic jewelry design, worn by celebrities from Elvis and Cher to John Mayer, Drew Barrymore, and Kacey Musgraves [Fig. 9]. Contemporary Diné silversmiths also continue to innovate, selling their work within the tourism trade but also to dedicated clientele, museums, and other Diné. The pressure for Diné silversmiths to make “traditional” jewelry is waning, with customers enjoying innovation in form, materials, and overall style. One of my favorite contemporary Diné silversmiths is Nanibaa Beck. Her work is sleek and unique, with designs that reference her late father Victor Beck Sr.’s work [Fig. 10]. I recently participated in a squash-blossom bead-making workshop with her at the Donald Claflin Jewelry Studio at Dartmouth College, which allowed me to more comprehensively understand the skill and time needed to make these designs.

This squash-blossom necklace in the RISD Museum collection [Fig. 1] is included in the Being and Believing in the Natural World: Perspectives from the Ancient Mediterranean, Asia, and Indigenous North America exhibition. This will be the first time it will be on view for the public since it was first accessioned in 1955. Conservators Ingrid Neuman and Bri Turner and I spent about ten hours together polishing it for the exhibition [Fig. 11]. As we worked, I thought to myself, “How did this necklace get so far from home? What story does it tell? What brought it to Providence?” I will probably never know, but it was rewarding to work with a piece from my tribe that never had much attention before. I hold in high respect the artist who created it.

For Diné silversmiths, artists, and people in general, the spirit of t’áá hwó ají t’éego—it’s up to us—continues and moves us forward. Many museums and institutions, including the RISD Museum, are now attempting to do more holistic work stewarding our Native American art collections with more accurate attributions and increased crediting. And we’re giving more attention to works like these, with no recorded stories but deeply meaningful pasts.

- Diné, our name for ourselves, literally translates to “the People.” Diné is often used interchangeably with Navajo, our tribal government name, given to us by Spanish settlers in the seventeenth century.

- Anthropologist John Adair wrote in 1945, “Because of the conflicting evidence, the origin of silversmithing can not be accurately dated, nor is it likely that it will be in the future.” Adair, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1945), 6.

- The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, 6.

- “The Long Walk,” Native Knowledge 360° Education Initiative, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/navajo/long-walk/long-walk.cshtml.

- Adair, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, 9.

- Theodore Brasser, Native American Clothing: An Illustrated History (Buffalo: Firefly Books, 2009), 188.

- James D. Henderson, “Meals by Fred Harvey,” Arizona and the West 8, no. 4 (1966): 305–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40167249.

- Lucy Fowler Williams, Water Wind Breath: Southwest Native Art in the Barnes Foundation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022), 28.

- Mark Bahti, Silver and Stone: Profiles of American Indian Jewelers (Tucson: Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2007), 12.

- Dexter Cirillo, Southwestern Indian Jewelry (New York: Abbeville Press, 1992), 68.

- Adair, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, 44.

- Cirillo, Southwestern Indian Jewelry, 73.

- Peter Iverson, Diné: A History of the Navajos (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002), 32.

- There is a tufa stone mold in the RISD Museum collection (Diné [Navajo], Jewelry Mold, late 1800s, Gift of Dr. Otto Kallir 42.287). A butterfly design was carved into the stone and the mold could have been used to make a silver pin, ring, or cuff.

- Cirillo, Southwestern Indian Jewelry, 79.

- “Four Worlds and the Importance of Silver and Turquoise,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WiyKXlEWoOQ.

- Adair, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, 37.

- Adair, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, 31.

- Adair, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, 24.

- “Stamping,” Garland’s Blog, https://www.shopgarlands.com/blogs/news/70546755-stamping.

- Special thanks to Shane R. Hendren (Diné) and Jeff Georgantes for their silversmithing insights on the technical aspects of this necklace.

- Peter Iverson, Diné: A History of the Navajos (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002), 79.

- Williams, Water Wind Breath, 29.

- Andrew Curley, “T’áá hwó ají t’éego and the Moral Economy of Navajo Coal Workers,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109, no. 1 (2019), 71–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1488576.

- Nancy Marie Mithlo, “No Word for Art in Our Language? Old Questions, New Paradigms,” Wicazo Sa Review 27, no. 1 (2012): 111–26, https://doi.org/10.5749/wicazosareview.27.1.0111.

- “Census: Navajo enrollment tops 300,000,” Navajo Times, July 7, 2011, https://navajotimes.com/news/2011/0711/070711census.php.

- “Significant [sic] Behind Navajo Traditional Clothing,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h_A3HmegYJ0&t=439s.

- Adair, The Navajo and Pueblo Silversmiths, 44 n. 12.

- Williams, Water Wind Breath, 146.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.