Image

Abstract

Gender stereotypes propagate through generations like a loop without a clear start or end, constantly reinforcing and being reinforced by the constructed, gendered system of information around us. For this project, I take the start of parenthood - the moment when new parents begin to learn everything about newborn care - as a critical point to encourage gender-neutral parenting mentality and eventually, to fill the gender gap in parents’ mental load.

About the binary scope

Throughout the development of this project, I have been frequently asked about why it is framed within a gender-binary context. This is mainly because the big problem (“why and how gender stereotypes are constantly propagated from one generation to the next?”) with which I started my research mostly happens to heterosexual nuclear families, which is then a structural result of gender binarism. Though one of my final goals is to explore the idea of gender-neutral parenting mentality and I try to avoid using the words “mom” and “dad”, I find it hard to replace a real, binary voice, offered by my interviewees, with a more generalized “them”. That being said, I want to stress that parents who identify as non-binary do face a lot of challenges resulting from the binary norm of most societies and cultures. Within the scope of my research (young Chinese families), the very fact that my randomly selected interviewees all have clear binary gender identifications could precisely imply how unseen those non-binary parents would feel and thus the amount of struggle they would face in day to day life. I believe this topic deserves a whole different study that highlights the non-binary subjectivity instead of incorporating this unique identity into the umbrella of “parents”.

Image

Image

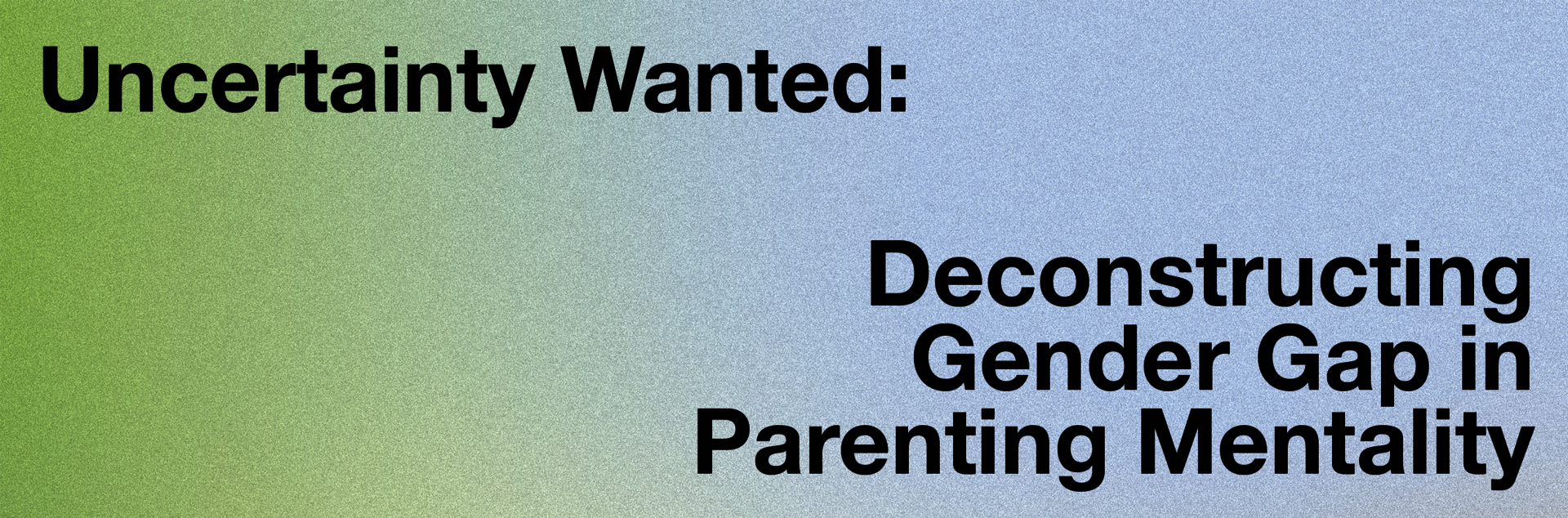

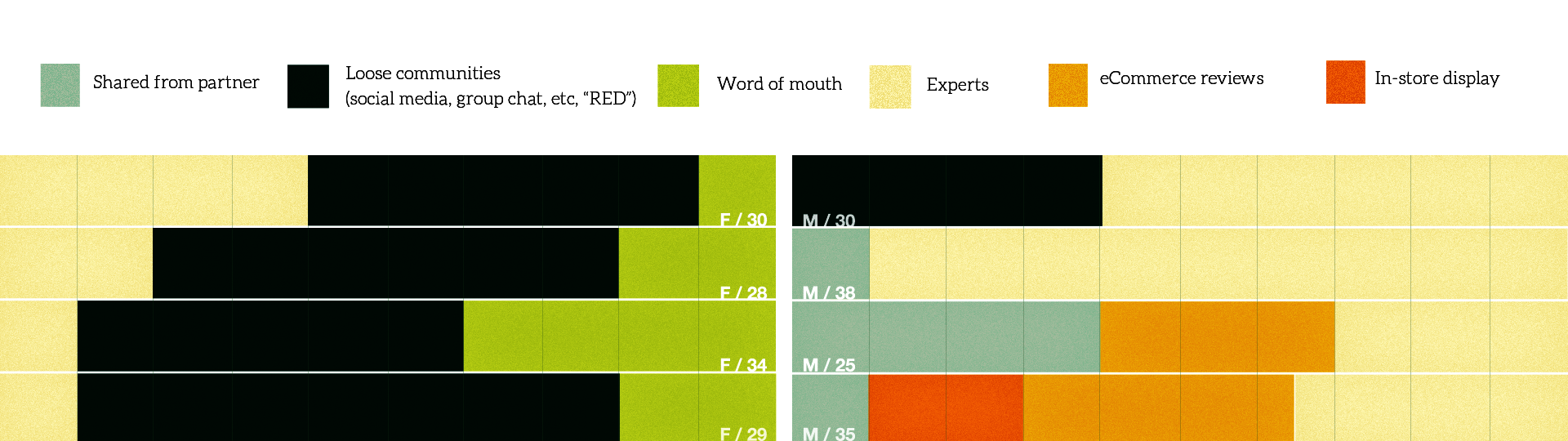

Based on data collected from interviews with eight new parents and a quantitative survey conducted with 53 samples (male parents age 26-40 living in major cities of China), we can easily tell the difference between male and female parents’ focuses on their newborns. For both fun parts and stressful parts, female parents’ answers are centered on activities in which the newborns are the more crucial participants, whereas male parents’ responses to fun and stressful parts lean towards activities in which either they themselves are the sole participants or they are equally crucial as the newborn.

In other words, female parents’ sources of happiness and anxiety are closely tied to their role as the baby’s “caregiver” while male parents‘ sources of happiness and anxiety are more likely related to their role as the baby’s “companion” or “role model”.

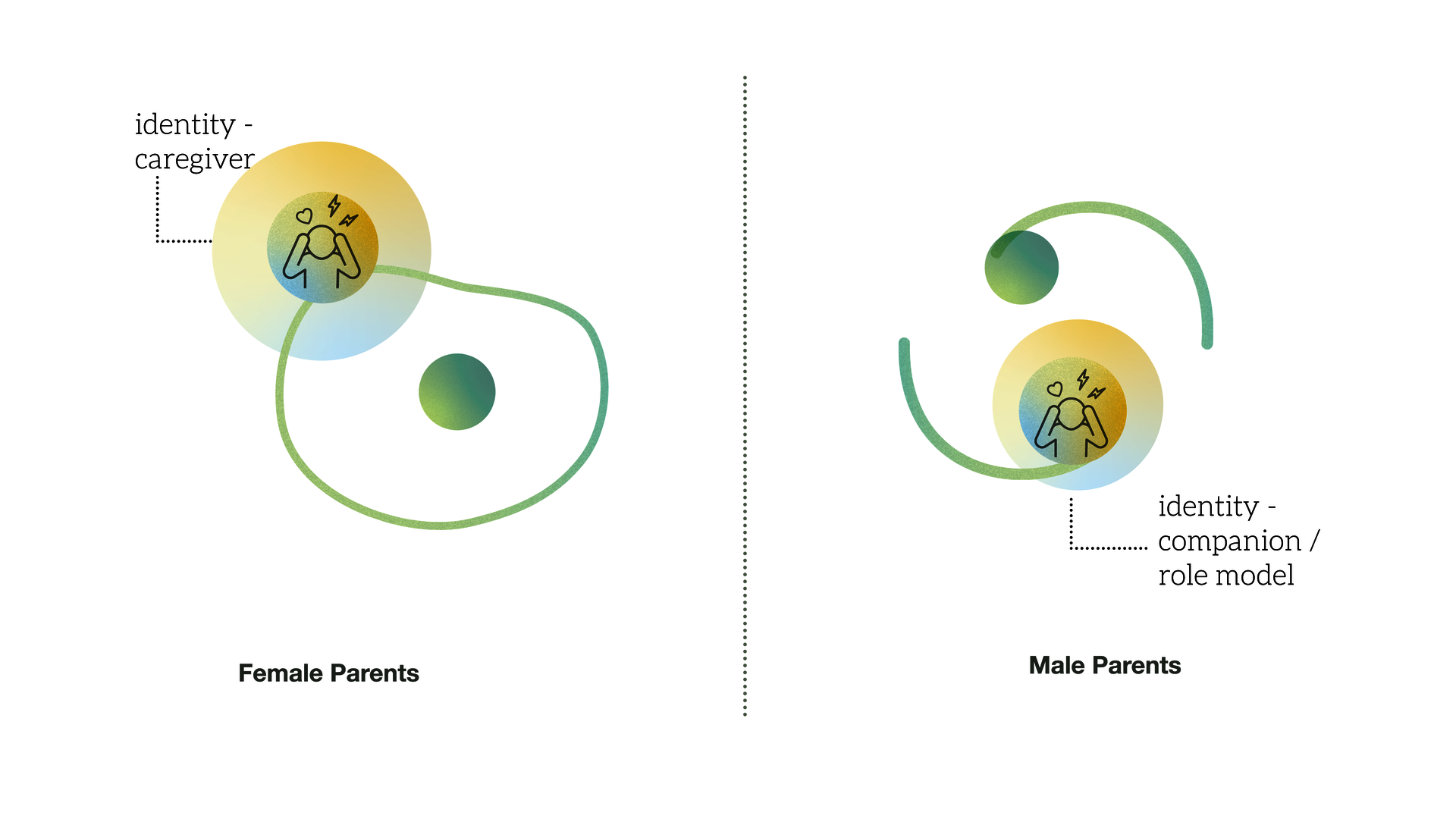

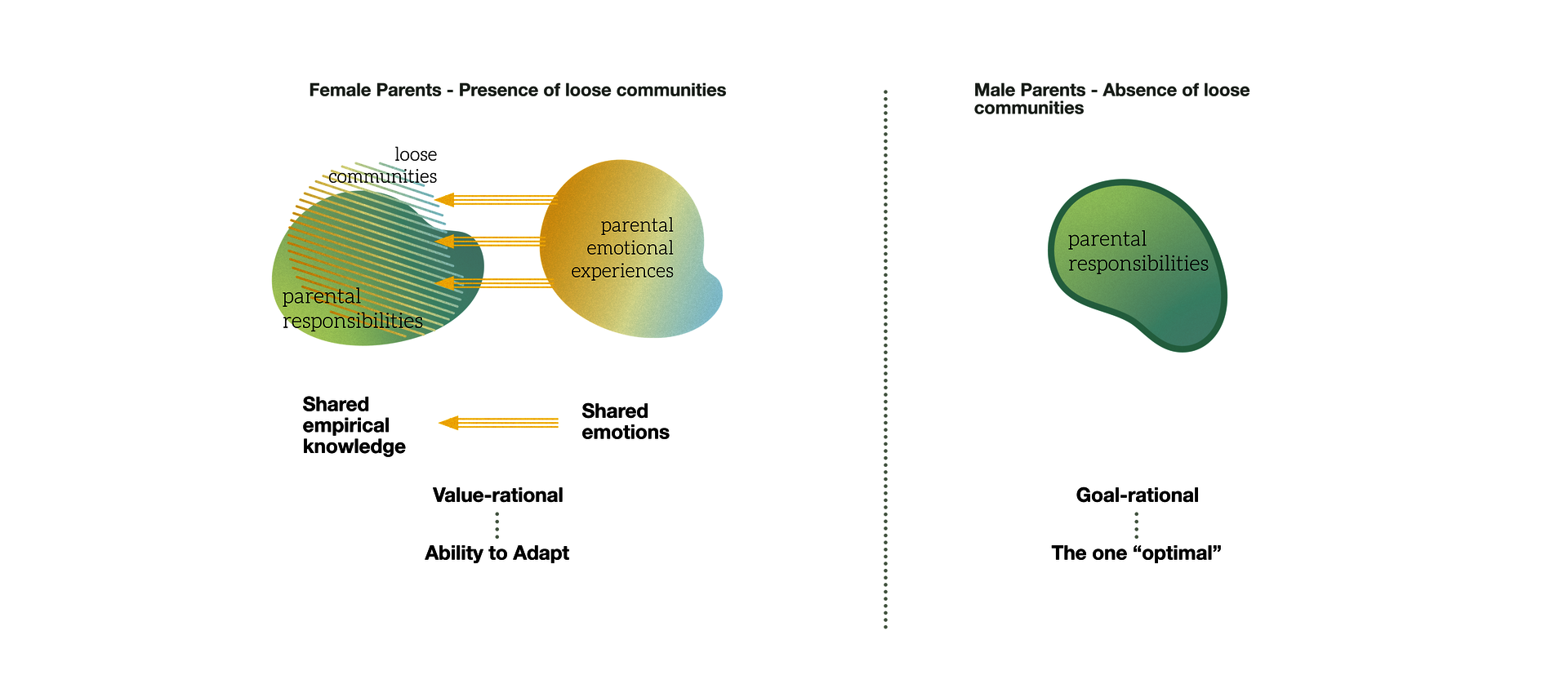

This is not saying male parents are unaware of their responsibility to care. In fact, both narratives and survey results have shown that male parents do actively learn about newborn care and participate in intimate care work. What the finding above really tells us is that male parents have unconsciously separated their parental responsibilities and their parental emotional experiences while female parents have them mostly overlapped. As a result, despite the similar level of awareness regarding their responsibilities after they know about the existence of their babies, such awareness does not transform into actual physical and mental workload for female and male parents on an equal level.

Image

Image

▲ "How did you learn newborn care skills and acquire information on related products?"

How did that separation start? The answer might have something to do with the different compositions of male and female new parents' information sources and more importantly, how those compositions have affected their emotional journeys of information acquisition.

A big part of female parents’ knowledge source consists of different forms of “loose communities”. These communities could be online and offline, relying on various social media platforms and formed among colleagues, neighbors, friends, loyal customers of the same baby product store, and even strangers.

When information on baby products and care tips is shared, anxieties or other mental stresses are shared at the same time. Since the user groups of these platforms are highly gendered, such shared anxieties hardly reach male new parents.

Image

The different ways through which new parents gather information and make sense of their system of knowledge — characterized by the presence/absence of loose communities — could be better understood with Max Weber's model of ideal types of social actions.

For male new parents, the action of learning about newborn care is mostly a goal-rational one, meaning that they tend to optimize the efficiency to find the "universally" best solutions to known questions. In this case, the means through which they reach their end goal is just a tool.

In contrast, female new parents tend to act in a more value-rational approach when doing these same tasks, meaning that they believe in the value embedded in their means (learning from loose communities). In this case, that specific kind of value is the capability to quickly adapt to potential problems—which could only be gained through learning from all kinds of lessons and mistakes. Therefore, instead of prioritizing efficiency, they prioritize the value lying in their exchange of empirical experience with their loose communities.

In our daily life, there are certain things that we learn and seek after in a goal-rational way and other things in a value-rational way. In most cases, the goal-rational category represents what we think we are good at (or even just what we want ourselves to seem good at) whereas the value-rational category represents what we actually have gained expertise in—through confronting uncertainties, experiencing mistakes and sharing lessons learned with others.

Image

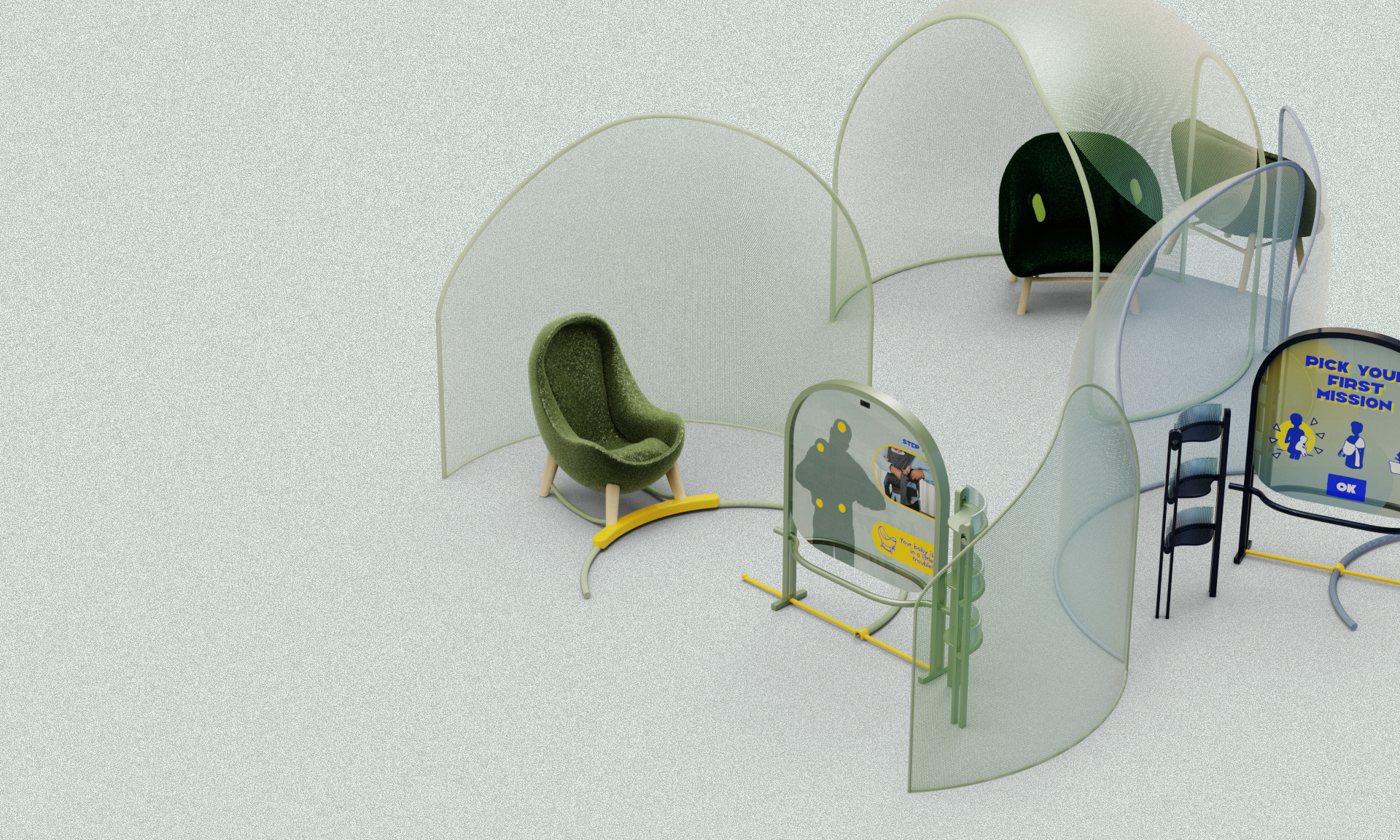

For those who have learned about newborn care with a goal-rational mindset, can we use the baby product retail space to make the empirical learning process in newborn care more visible and to normalize the experience of struggling with uncertainty (hence vulnerability) involved in it?

Why retail space? Unlike the online world of social media and digital consumerism where users have been selectively diverted into gendered information platforms from the very beginning, brick-and-mortar baby product stores offer interesting opportunities to fill this gender gap in parenting mentality. According to my conversations with new parents, couples generally go to baby product store together - this provides a good start for creating on-site experience since they are already present not only with their partners but also with a group of peer parents, namely a loose community. Moreover, such trips typically complement their online shopping experience by offering a more tangible and straighforward experience of the products. In this sense, baby product brands do have the incentive to provide a more impressive on-site experience.

To recreate the empirical learning process in newborn care and to help normalize the struggle with uncertainty involved in it (hence the experience of vulnerability), I designed a system of interactive furniture to be used as a part of baby product store experience. The system consists of three groups of components. each offering a distinct possible approach to this end goal.

Image

Image

I "Shaky Cradle"

Imagine what it would feel like if the traditional "try before you buy" experience is added with an interactive tutorial station where your partner's physical experience of sitting in a cradle-like chair would drastically change as a form of real-time feedback on your performance.

For value-rational parents, the experience of struggling with uncertainty is often intensified by their own awareness of the impact their decision-making could have on the baby. This is also why they see agility/adaptability as a critical ability. This design explores a possible way to translate and exaggerate this power relation together with such self-awareness to the interactions between partners.

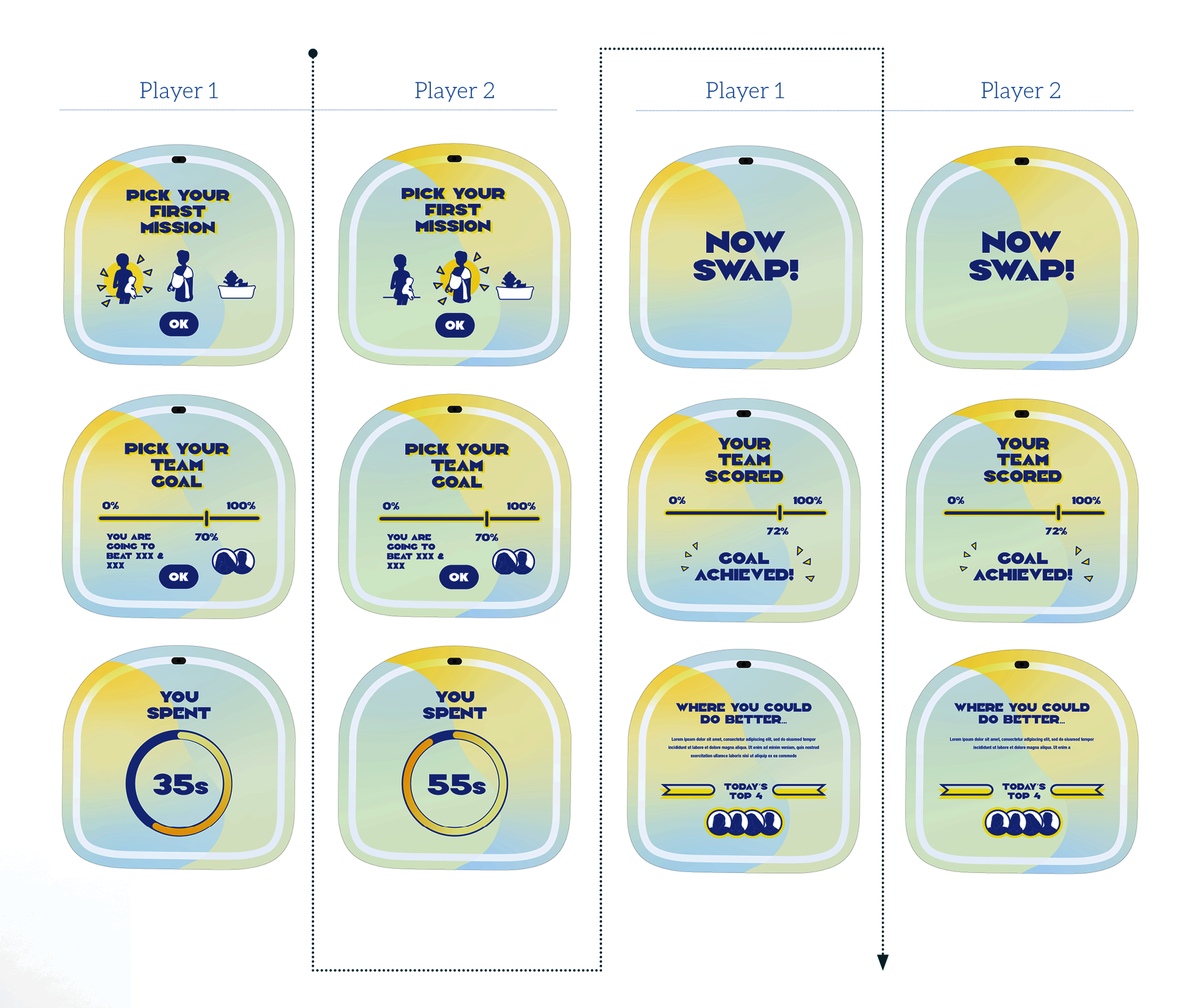

II "Team Up"

Image

Image

Image

Image

III "Pondering Chair"

As a result of discrepant approaches to learning about newborn care skills and products, the customer journeys of the value-rational and the goal-rational at the baby product store would differ a lot, too. The goal-rational parents would usually find themselves looking for a seat to rest as they wait for their partners' extended journey to end.

The Pondering Chair is designed in disguise as a welcoming and comfortable place to take a rest. Through stimulating the user's curiosity with a pair of visual hints and inviting the user to interact with the extendable "arm", the chair would then softly force the user's body into a bottle-feeding position. Despite their clarity as visual hints, the two color-coded patches, which have small magnets on the back, won't easily attach to each other without the user spending some time to figure out the exact location of the matching magnets.

Image

Image

Image

Image