Zibby Jahns

Holding Spaces

I’ve focused my graduate studies at RISD on the conceptual and social function of chairs as an investigation into comfort and grief. Grief is an apprehension: defined both as “to grasp” and as “anxiety/loss”.

With the multitude of deaths due to the inadequacies of our government and healthcare system, and the general anxiety everyone has been feeling through this pandemic, it has felt difficult to grieve for any individual person, in person. We have to grieve in the ways capitalism has taught us: silently, behind closed doors, without much time or fuss or drama, mourn with dollars and move on. In spite of this, I still find it important to carve out space for memory, honoring and celebration.

More young people died of overdoses last year than from Covid. What is often lacking societally for people who use drugs is exactly what they are seeking. Why has it become so stigmatized to offer comfort to people who use drugs? Drug use is so rooted in finding a stand-in or surrogate for comfort. Our society does not create space for collective joy and grief. Most that exist are offered only in exchange for capital.

As I explore notions of “holding”, of the spaces I’ve hidden in, provided for others and the trauma that may reside therein, I am confronted with the assigned woman’s body as a site for grief and care, an armature of pain and healing. In Michaelangelo’s Pieta, Mary is a chair—her body has been newly aligned by the sculptor into one of an armature, out of bodily proportion to what is physically possible and concealed by excessive drapery. In Pieta, Mary holds: presence and absence; life and death; human and deity. My existence and impression in the spaces I’ve created feels more like an apparition than a protagonist, an attempt to move like the ghosts I know. Do ghosts sit? How do we trace impressions of air and build altars of comfort to spirits? What kind of work is required to build a space that contains loss?

Make Yourself Comfortable

It has occurred to me as I make spaces for others to grieve or that embody my pain, I have not built the space that I want to exist in. I have found that most of the time, I just want to hide. I don’t want to perform. As an adult, I know that the thing that makes me feel best is the joy and play we were told to leave behind in childhood. I can’t seem to design a play sculpture that exists for me alone–it is contingent upon a friend to join me. Children are the most honest about their feelings. Even if these feelings are difficult to articulate, or change dramatically minutes later, children are true to their emotions. So I have looked to the spaces I searched for when I needed an immediate remedy for my pain as a child. I was a perennial hider, in the back of closets or behind curtains. It felt so safe to be out of sight in a dark and soft space, still able to hear the commotions in the real world.

The most perfect, special space I thought had come from a dream. It was a place I imagined so often, I thought it could not be real. In my moments of extreme childhood sadness I tried to will it into being. During one meltdown as a kid, I ran to the island in the kitchen, frantically scanned the sides for an opening and beat on its walls, trying to get in. My mom asked what I was doing and I said that I thought there was a door somewhere and I could go inside. She looked at me with pathos and understanding and told me that was in my grandparents’ old house, that grandpa had made a small opening in their island and filled it with all the softest things, and I was so young she was surprised I could remember. In my dreams the softness had taken on fantastical proportions–the walls weren’t wooden, but made from the same fabric as my blankie, as were the shelves–thin cotton somehow affixed to the blankie walls to hold beloved old and vanished plush creatures. The light inside was like a womb, pink and yellow. Perhaps it was the color of sunlight softly humming through my blankie when I draped it as a tent over my child self, trying to emanate the feeling I had in the hiding place my grandpa had built.

More young people died of overdoses last year than from Covid.

Has our society restructured around it? Have institutions extended the same urgency to harm reduction as they have to the pandemic? Socio-physiologists have studied the correlation between chemical responses in infants’ cries of anxiety and the soothing of a caregiver to the experiences of opioid withdrawal and use in the human body. Why do we make it so hard for people to access joy and comfort, and then criminalize a synthetic substitute for the two? Capitalism strips individuals of community. Modern technology alienates people from modes of production directly related to survival and beauty. We have been taught to buy disposable care and simulacrums of connectivity–why would it surprise anyone that humans have sought out chemical stand-ins? Why stigmatize someone who uses drugs into further enclaves of isolation?

What is often lacking societally for people who use drugs is exactly what they are seeking. Why has it become so stigmatized to offer comfort to people who use drugs?

Drug use is so rooted in finding a stand-in or surrogate for comfort. Our society does not create space for collective joy and grief. Most that exist are offered only in exchange for capital.

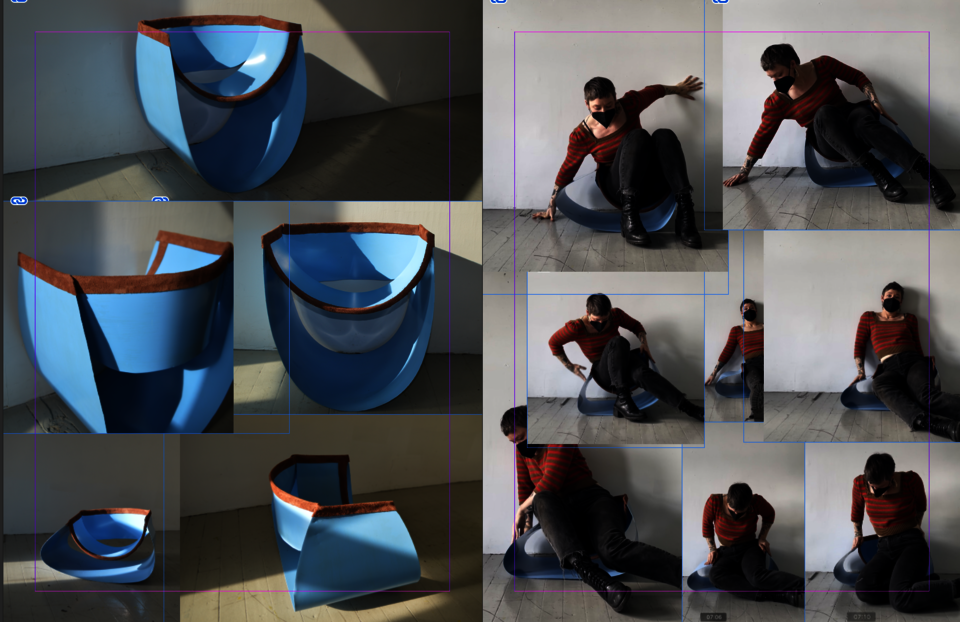

I sewed the soft sculpture in this 2021 piece, entitled “Make Yourself Comfortable”, out of silk and filled with discarded couch innards and more stuffing than I could find in the small state of Rhode Island. My attempt was to create a body like (or multiple body) form that was inviting for release, but weighed me down instead of propping me up.

In November 2021 I carried the 70 lb structure around an abandoned IBM facility in Kingston, NY for three hours and attempted to sing the songs in my head.

Image

photo credit: Sarrah Danziger

Practicing grief

With the multitude of deaths due to the inadequacies of our government and healthcare system, and the general anxiety everyone has been feeling through this pandemic, it has felt really difficult to grieve for any individual person, in person. We have to grieve in the ways capitalism has taught us: silently, behind closed doors, without much time or fuss or drama, mourn with dollars and move on. In spite of this, I still find it important to carve out space for memory, honoring and celebration.

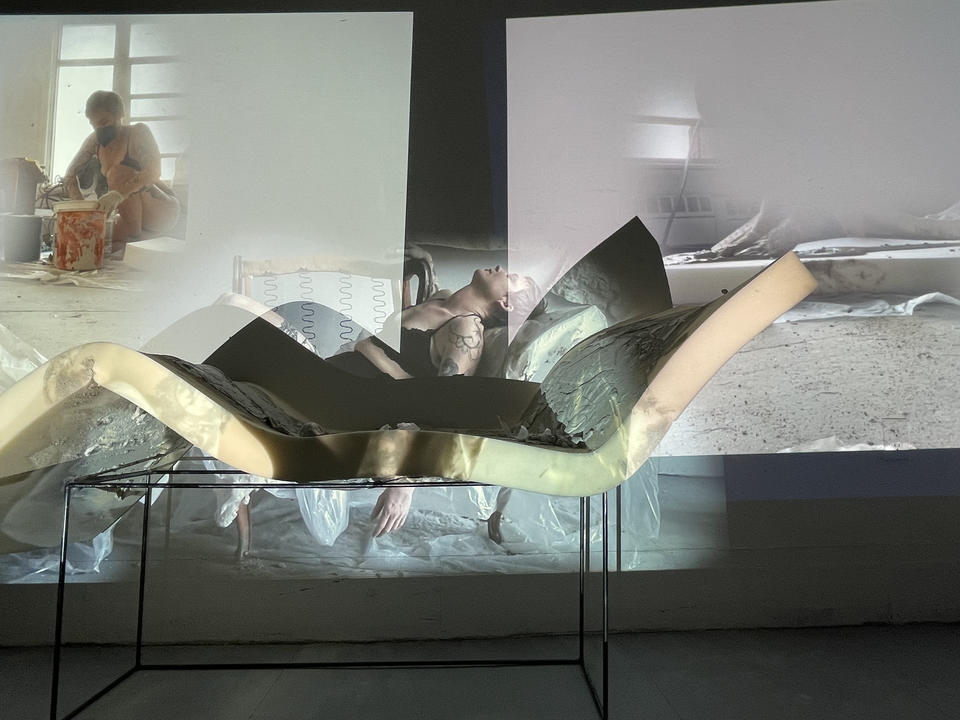

How can we find solace when we physically can’t hug those we love, lest we endanger those who are more vulnerable than we? Loss constricts the body, hardens the fascia. I practice being present. I remember with my body. I made this piece, a reflection of my own body, as an offering, a place for people to let go, go within, and grieve in the isolating months at the beginning of Covid. Building this sculpture was a way for me to hold strangers who were hurting at a time when we could not touch each other.

I made this object for reflection, both visually and viscerally. As with grief, this object is not welcoming. It takes balance and resolve to overcome the fear of lying on this steel object, suspended in the air. But as one person who experienced it said, the act of lying on it makes you aware of the breath, the body, and allows release.

Image

Aryana Polat interacting with the piece "Practicing Grief"

Holy Ghosts

What we learn about death we learn first from our families. Originally, these rituals were designed to help community move through the motions of grief, traditionally bestowed by religion. My first funerals reflected both sides of my family: the sensuous and awe-provoking elements of the Catholicism practiced by the Czernek/Jahns, and the minimalist and heady reform Jewish ceremonies on the Metcoff side. While I was not raised Catholic, and was reminded as my sisters and I remained seated in the pews during communion that our family was different, I appreciated passing into this space of mystery, of echo, of smells on the West side of Chicago when I came to mourn the passing of my grandmother, aunt, uncles, cousin. I was honored to act as pallbearer and be invited to read lines of scripture to the congregation that were unfamiliar to me. It didn’t feel like mine in the moment but I wanted to be connected to the lineage of worship that half of my family followed.

Did my grandma practice these same traditions before she came to America? How long had this opulence been a part of their worship? When had the traditions of Slavic paganism slipped away? How had my family exchanged these traditions for the promise of whiteness? How were the radical tenants of reform Judaism that my great-grandfather founded in mid-Western synagogues in service to assimilation? Who was the last person to wrap Tefillin around their limbs? Why does gender equality need to mean a loss of thousands of years of rituals?

Besides the obvious beauty of reliquaries and Catholic churches, the stark contrast of displaying images of the human form in a house of worship became so mysterious and fascinating to me. I feel deeply connected theologically and spiritually to Judaism, especially in its embrace of Questioning as a holy pursuit. I come from a long line of grandfathers inscribing sacred texts written over millennia as arguing Talmudic rabbis investigating theoretical possibilities and gray areas that exist in our conception of life. I feel grounded by Judaism’s connection to the earth through seasonal traditions which tend to land community. I feel tied to the rituals of rocks and decomposition. My interest in identifying the space of holding feels deeply Jewish, but my manner of representing it also feels deeply rooted in the Catholicism I’ve always felt like a tourist in, but have known in some ways is also coursing through me.

Reliquaries are conceptual cabinets of curiosity. They are dizzyingly ornate to conjure Divine Wholeness only present via a tibia or carpal. We are told that the thing of most value is the shriveled up stand-in for a person we must believe once was, someone who through good faith and moral ascended to heaven. The delicately gilded case and cloak are nothing in comparison with such salvation. They ask us to witness what once was, if only a myth or whisper. The space contained is the space of belief, an aurified suspension of cruel criticism, an elevation of the human to the divine, an earthly representation of ascension. How to take the toils and scars–the torture inflicted for piety of the unknowable–and remove the pain to instill belief in an afterlife? The blessing of forgiveness? A levity to adorn what drags us mortals down?

Image

Armatures of Absence

- Architecture

- Ceramics

- Design Engineering

- Digital + Media

- Furniture Design

- Global Arts and Cultures

- Glass

- Graphic Design

- Industrial Design

- Interior Architecture

- Jewelry + Metalsmithing

- Landscape Architecture

- Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies

- Painting

- Photography

- Printmaking

- Sculpture

- TLAD

- Textiles