For those unfamiliar with it, the Lost Cause of the Confederacy is the summation of efforts by certain groups, among them the United Daughters of the Confederacy, to commemorate the actions and ideologies of the confederacy. In stark contrast to the majority of germans, this movement sought to immortalize those men and women who gave their lives to divide the Union over their firm support of states rights on the distinct basis that owning slaves should be legal. Among their works are hundreds of statues erected to leaders and generals of the confederacy, whose statues and presence are a racist insult -and threat- to non-white citizens, and especially descendants of former slaves.

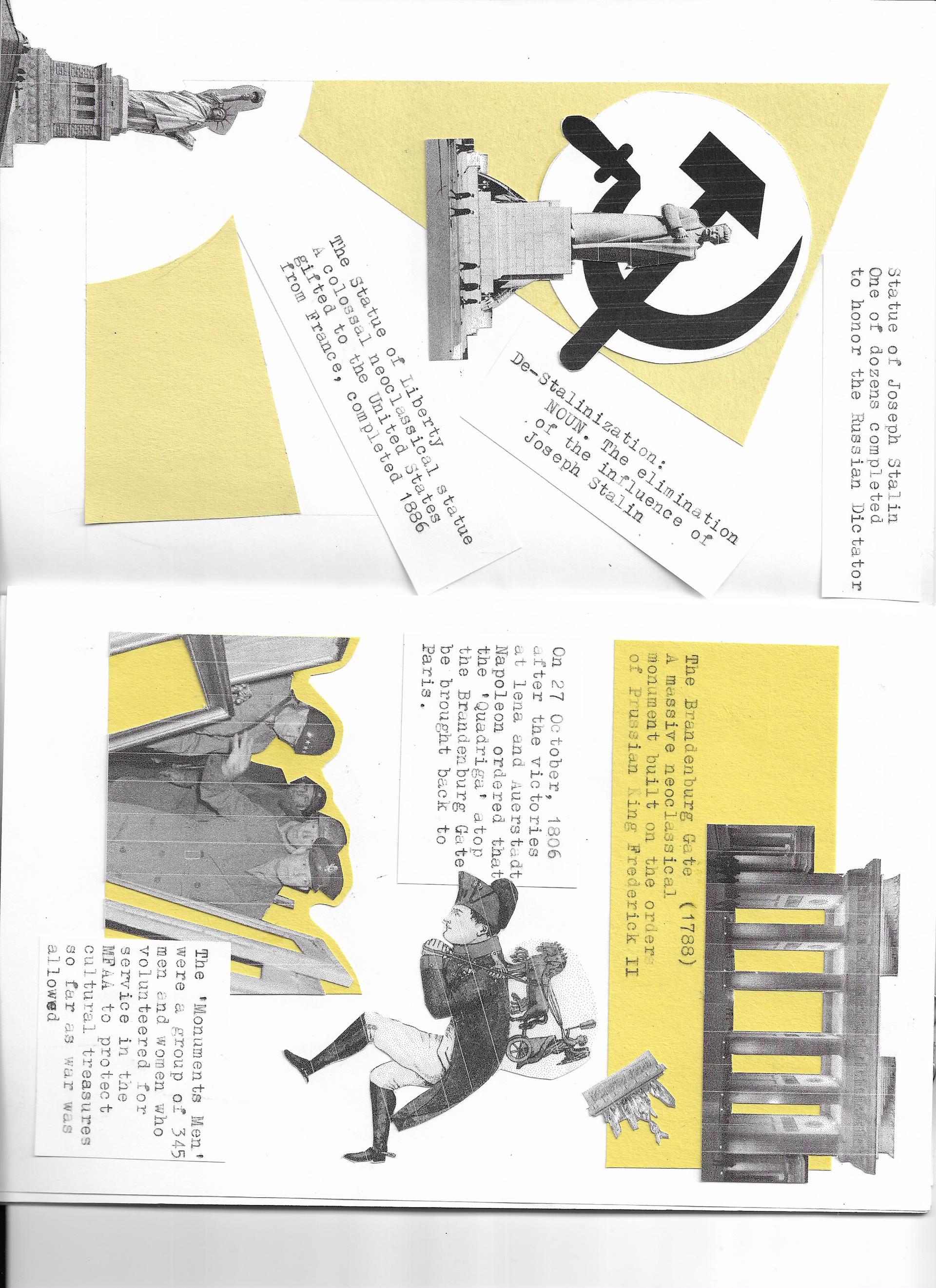

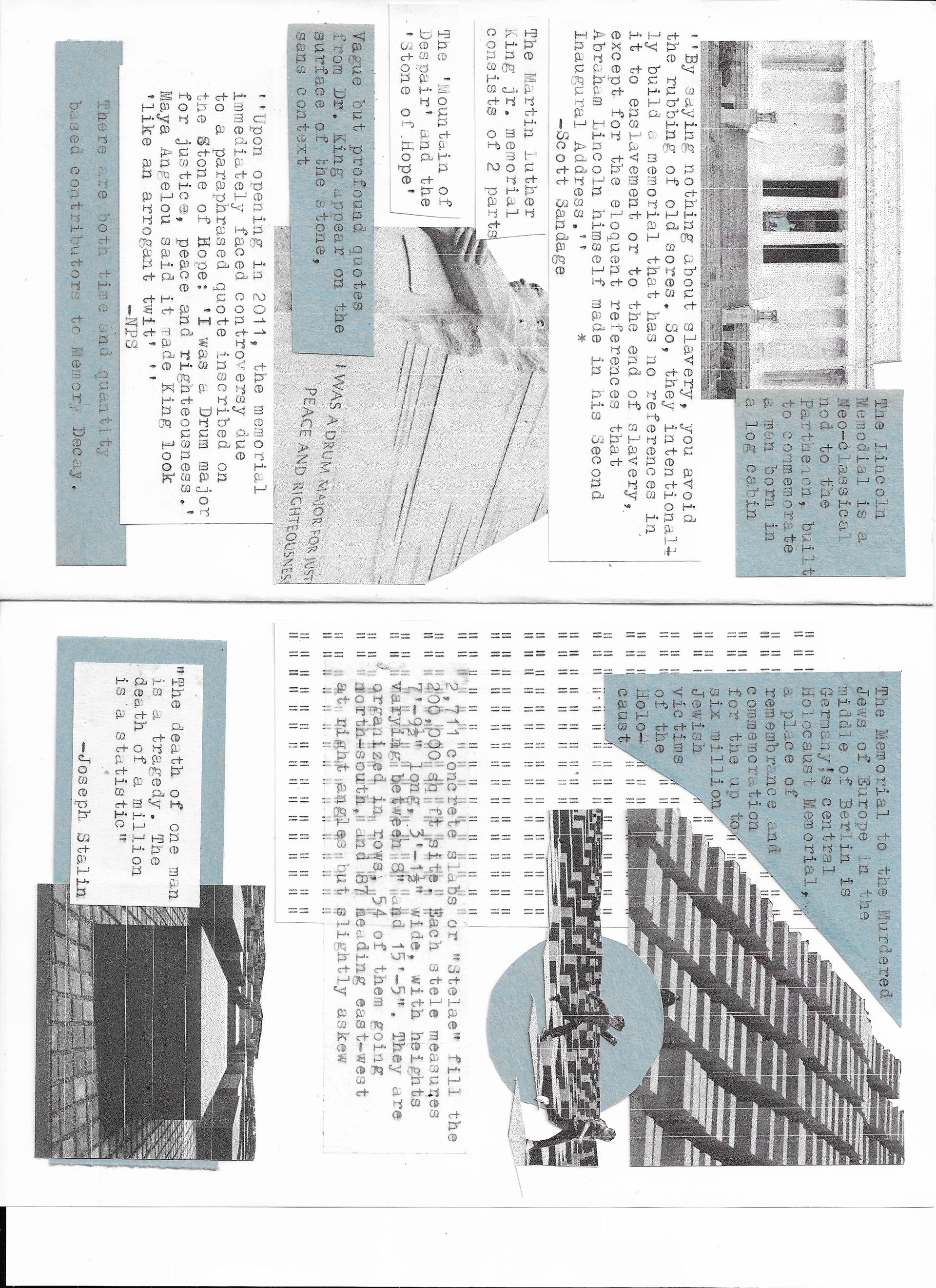

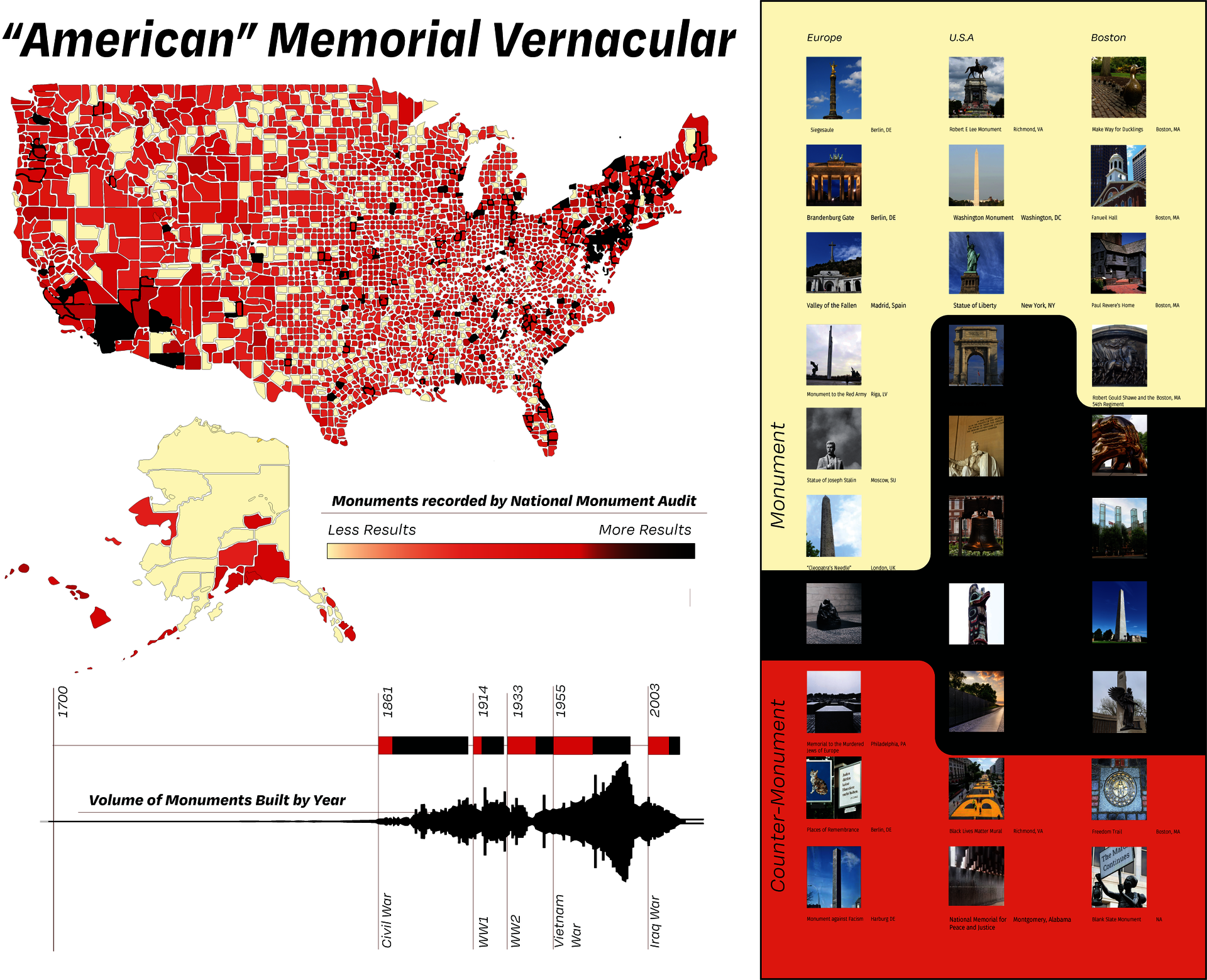

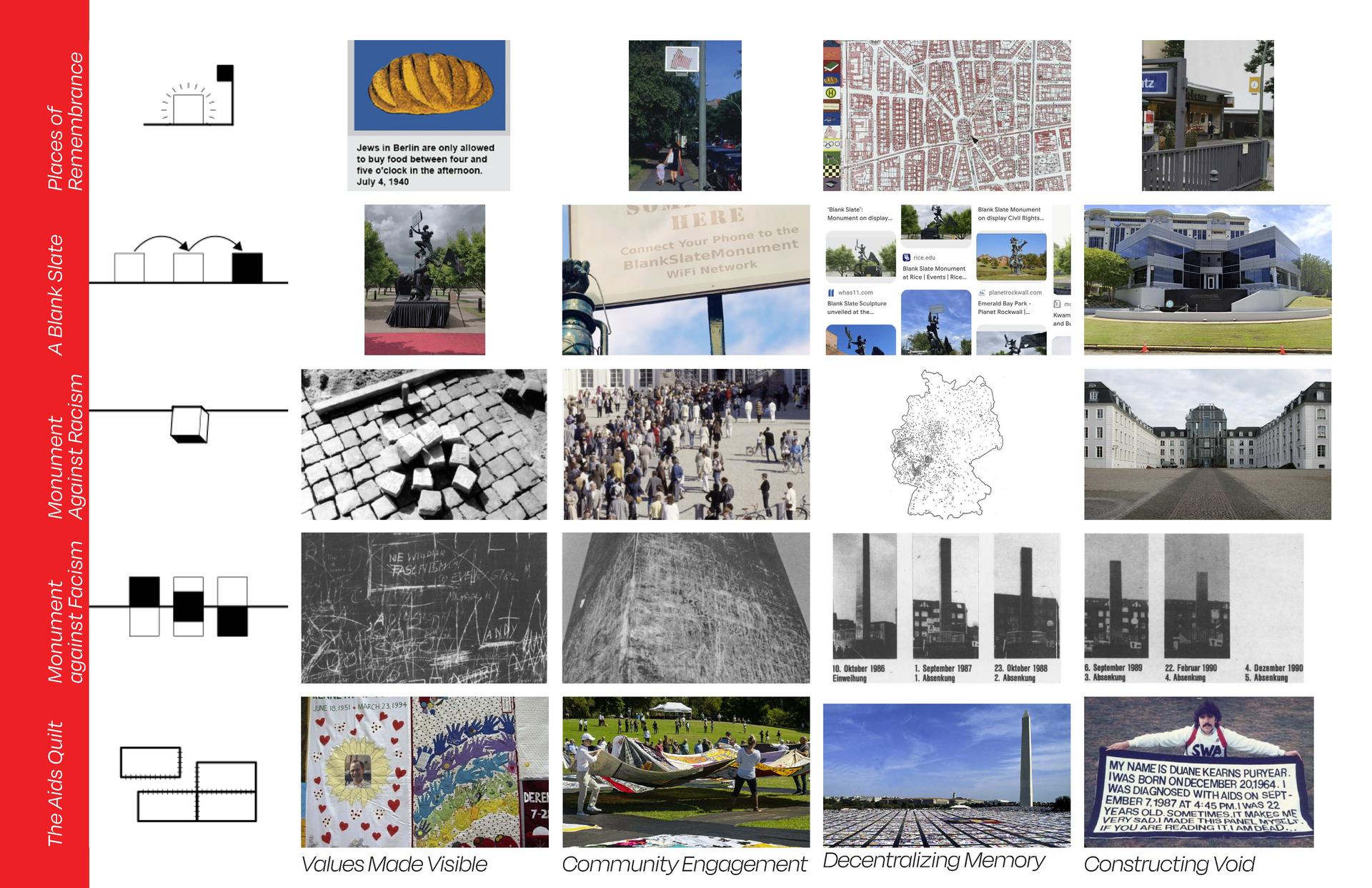

In learning more about these monuments, it became clear that their presence also hinted at a similarly sinister absence: the lack of monuments to non-white men and women, and the silence of their struggles, stories, and achievements was deafening. My research and conversations led me to the work of Monument Lab, a Philadelphia based non-profit public art and history studio. Among their many incredible “prototype monuments” was a body of data compiled on all recorded monuments in the United States. While still incomplete and constantly growing, this national monument audit led Monument lab to proclaim findings regarding what most American Monuments had in common. Beyond the astounding disparity between White Male Slave owners represented most commonly in monuments vs literally any other group, Monument lab also showed something that my research into German conceptual artists had begun to make clear: MONUMENTS ALWAYS CHANGE.

Despite efforts to place permanent markers of singular narratives into our cities and countryside, the monuments of our past are distinctly different from the monuments of our present. Whether it is physical deterioration, additions or subtractions, reframing, removals, replacements, or destruction by protestors, monuments are not the static monoliths we are led to believe they are. Monument lab took this as a call to do something, not only in the name of making more monuments for under-represented groups, but also approaching those existing ones that have done so much harm.

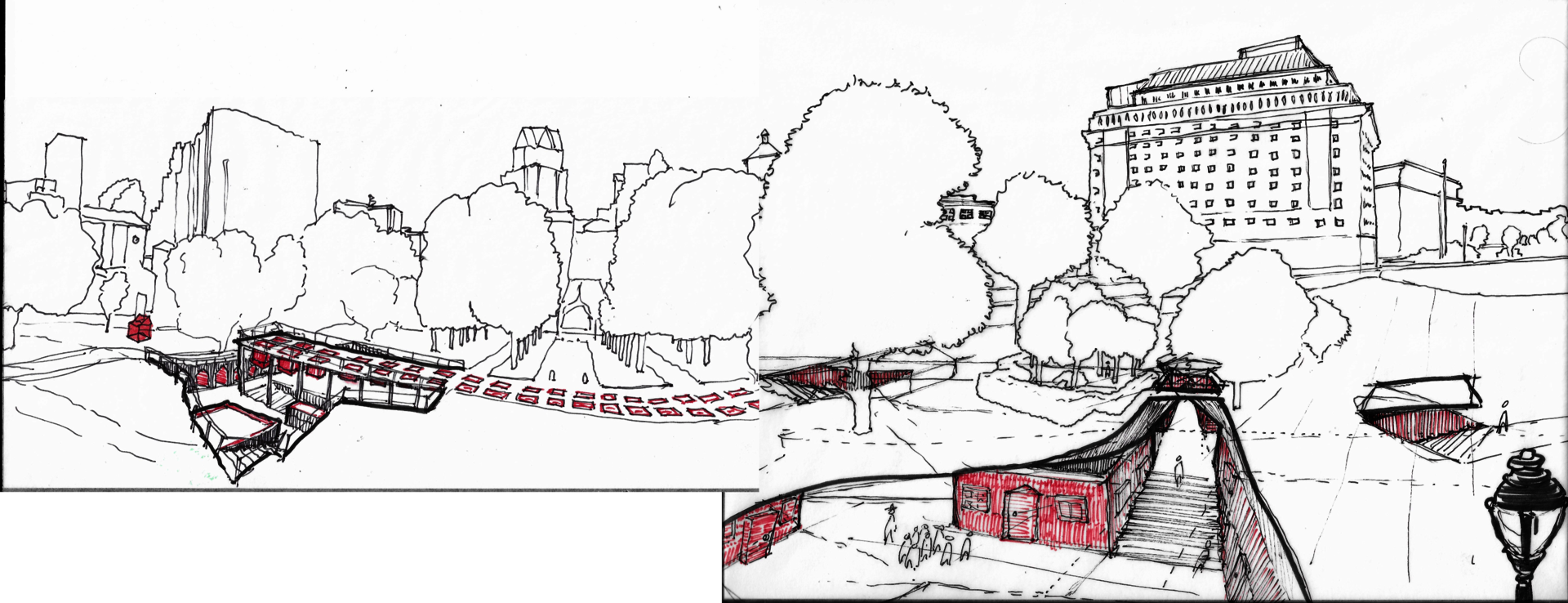

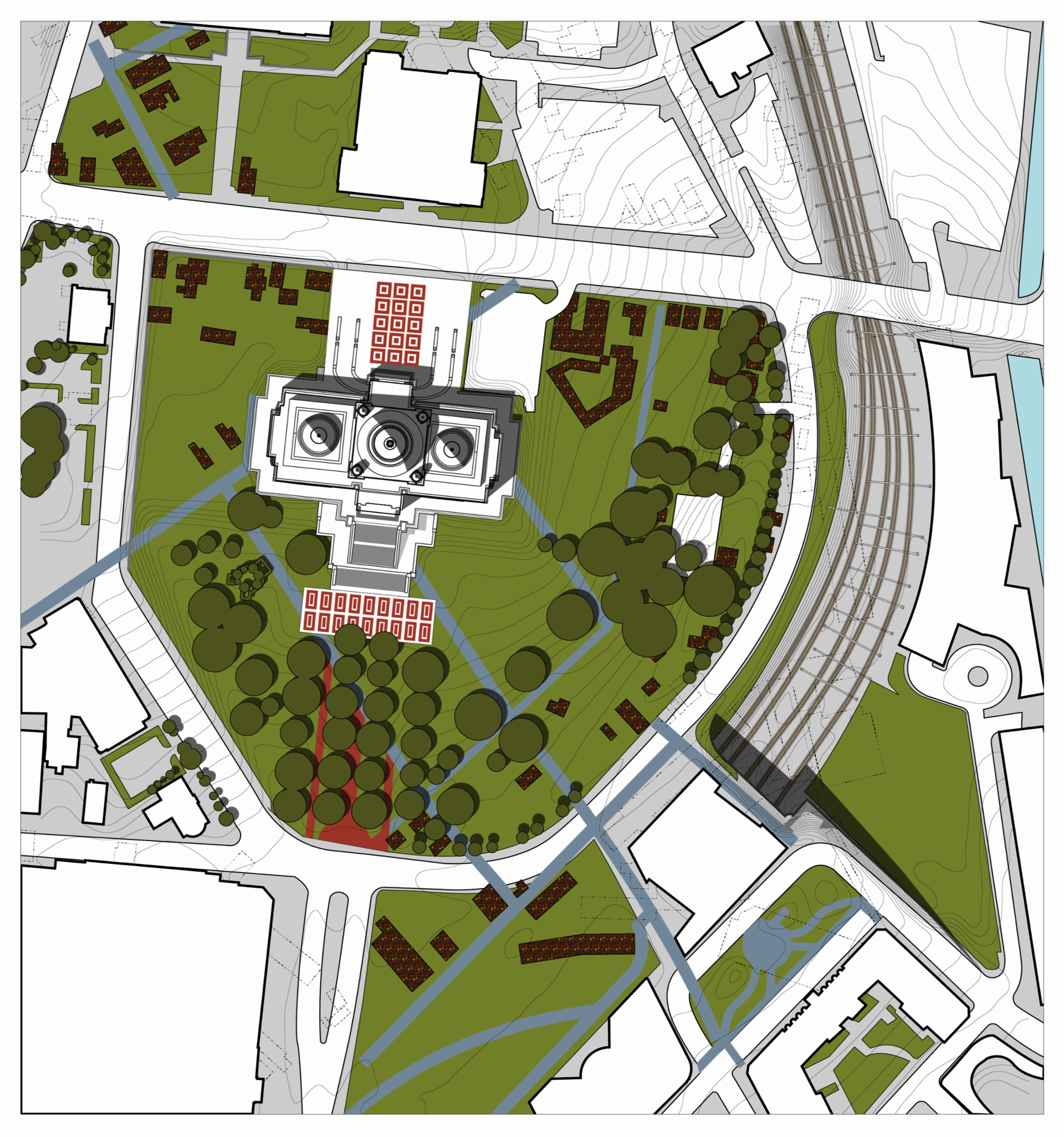

The convictions of Monument Lab led me to look deeper and find those stories around me that have been tamped down, paved over, and erased from our collective memory though force. One such story was that of Snowtown. A fellow classmate informed me of a working class black neighborhood that once occupied the northern bluff of providence, at a time when the slave trade still enriched the budding port city of Providence. This neighborhood housed many workers, ship-makers, store owners, house-cleaners, and more, who were often excluded from Providence’s projected image, despite their integral part in the city’s functioning. Reading more, I learned that the residents had been subjected to at least 2 attacks by white mob violence that played a role in labeling Snowtown as blight (although that term itself would not be used for projects of urban renewal for many more decades). As the 1800s drew to a close, eminent domain and the railroad companies made short work of the neighborhood, displacing an as of yet unknown amount of unnamed inhabitants, and silencing a formative chapter of Black Rhode Island heritage.

“...Perhaps no one monument could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject which it might be designed to illustrate.” —Frederick Douglass

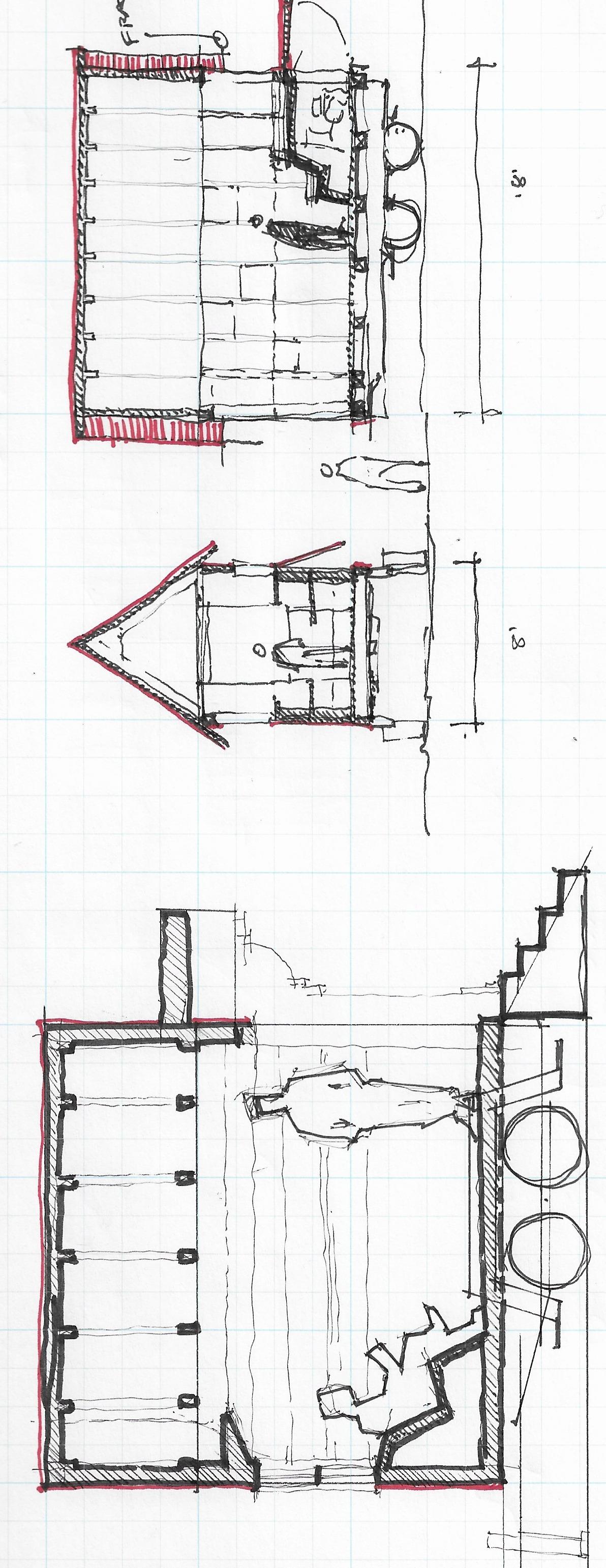

There may have only been one Snowtown, but its story has played out more than a thousand times across the history and geography of the U.S. Cycles of displacement are as American as apple pie, but the harm they have done is measured not in monuments and markers, but in the voids and scars upon our cities. Indeed, the story of snowtown echoes in the recollections of former residents of Lippitt hill and Fox Point. My research and conversations with my peers and professors made it clear that the city, and indeed the whole country, is having intense reckonings with cycles of displacement and dispossession. This became the source of my proposal for intervention.