Authored Subjectivity: An Extralingual Reading of Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi

It was the eve of Indian independence. After fourteen years of service in varying capacities as a scholar, teacher, diplomat, and novelist, the Urdu literary icon Ahmed Ali found himself at Nanjing University in China. He had just been appointed a Visiting Professor by the ruling British government of India and would spend two years teaching English at the behest of the British Council. Ending his tenure in 1948, Ali sought to return to his native New Delhi in India. However, the India he had left behind two years ago was not the one he hoped to go home to. In the time since his departure, his country had endured an unstable mitosis, splintering the subcontinent into two conjoined twins in a violent partition of land, livelihood, and language. One colony became two free nations, and yet, Ali became a new kind of prisoner. Having never stated his preference as a government employee, the then Ambassador of India in China K.P.S. Menon refused to let him return to India, arguing that as a Muslim he would have to go to Pakistan instead—which is where he would live until the day he died, never again returning to the streets he called home.

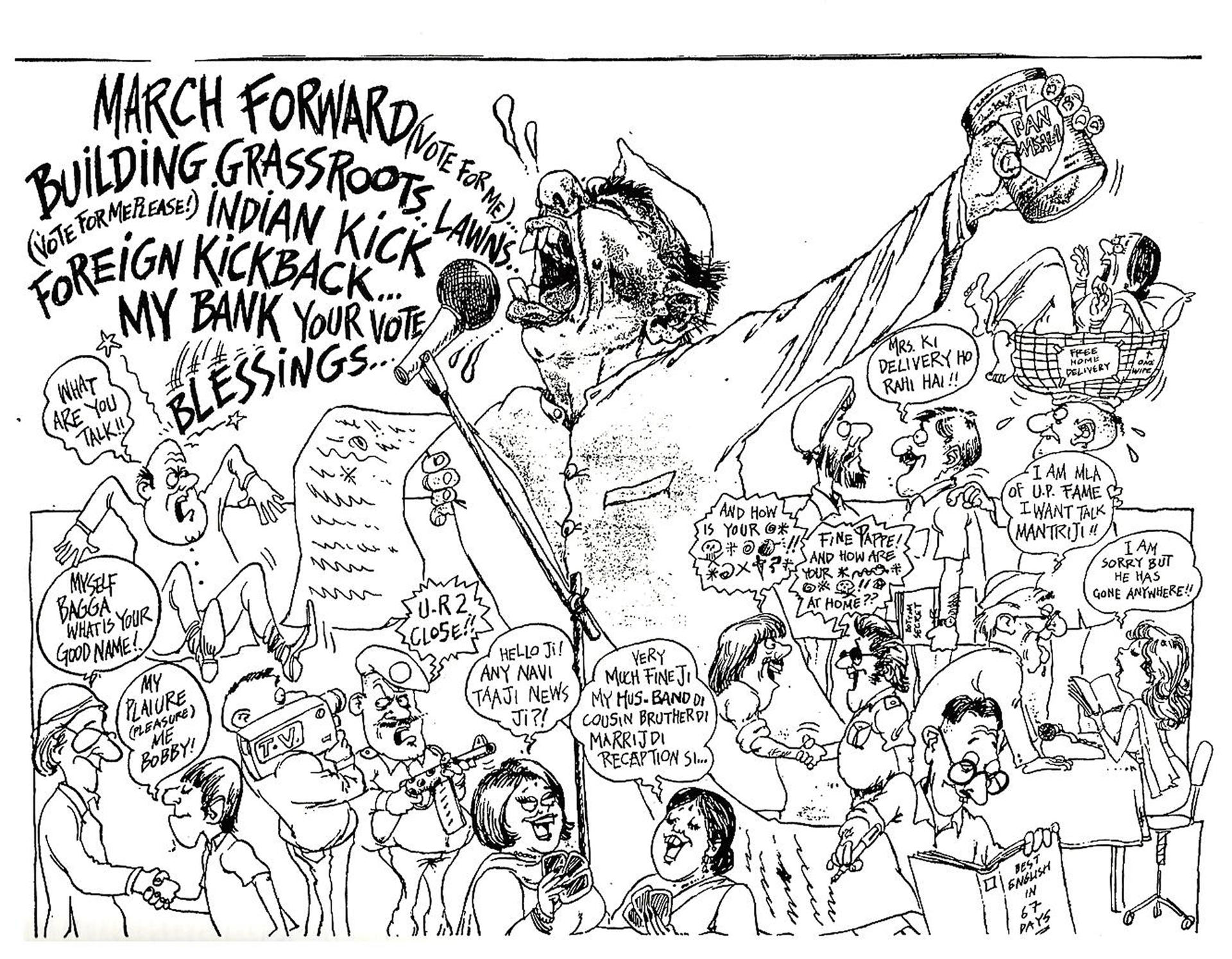

Eight years prior, at the height of the Progressive Writers’ Movement (PWM), Ali would write a prescient novel about his home. Written in 1940, Twilight in Delhi is the story of an Indian father struggling to negotiate the complex forces shaping Delhi in the wake of English colonialism, parallels that Ali would personally experience not even a decade later. Set between 1911 and 1919 in a newly-colonized New Delhi, the novel is book-ended by two revolutionary moments of change: on one end, the Coronation Darbar, which was an Indian imperial-style mass assembly that commemorated the proclamation of King George V as Emperor of India; and on the other, World War I. At the center of the novel, however, are its two protagonists, each embodying a specific sociocultural imagination: the father, Mir Nihal, and his nostalgic celebration of lost Mughal glory, and his son Asghar’s embrace of English notions of modernity in defiance of familial traditions. Albeit not stated explicitly, these two imaginaries capture a central tension within the novel, a loose binary negotiation of tradition and modernity, as understood and embodied by these two characters. I explore the negotiation of these subjective ideals through the metaphor of twilight (borrowed from the title of the novel), of a waning day slowly melting into the purple embers of a new evening, the slow middle between an end and a beginning. Reflecting on the novel, Sumatra Baral writes:

Twilight indicates in-betweenness and liminality – the position of Delhi between two languages – English and Urdu and two empires, the Mughal and the British. [……] Twilight, which usually hints at a transition between day and night, here posits itself between life and death, tradition and change, orthodoxy and progression.

This half-light semi-darkness speaks to the bilingual (if not plurilingual) colonial speakers’ experience of the in-between, of a sort of double consciousness engendered by their oscillation between linguistic traditions. To clarify, my concern here is not what Monica Schmid has described as language attrition or “the loss of, or changes to, grammatical and other features of a language as a result of declining use by speakers who have changed their linguistic environment and language habits” (11-17). Instead, I point to the psychological motivations and aftereffects informed by this linguistic dissonance, further heightened in the case of Twilight by Ali’s choice to write the novel in English, despite local criticism and constant rejection from British publishers. The novel was part of an enormous body of controversial work produced by Ali and his peers in the Progressive Writers’ Movement. These were Urdu literary dissidents, attempting to shake the foundations of religious and social orthodoxy through a radical retelling of North Indian lived experience, most notably in a collection of Urdu short stories titled Angaaray that would ultimately be banned. Yet Ahmed Ali chose to write Twilight in English. Could we read this as the author mirroring his younger protagonist’s English aspirations? Ali offers some clarification in a 1975 interview with the Journal of South Asian Linguistics:

I have been wondering why I write in English. [...] It was not because, as some people have said, that I wanted to curry favor with the British. That's nonsense. It was an escape for me from many things. I could not express myself in Urdu when I was young, so I had to express myself somehow and English was all right for them [his family] ~ it was the ruler's language, the baré sahib's [big officer’s] language, so they couldn't take objection to that in their minds. Their outlook was very orthodox, very narrow-minded. My older cousins had such an outlook, my aunt as well. [...] Urdu had been taken away from me because of the great resentment people—my uncle's family—had toward my writing in Urdu (JSAL 122-3).

His comments point to the position English held (and continues to hold) as a marker of social mobility and intellectual progress in Indian society. Could this explain the motivations behind his choice to write in the language of the colonizer? Speaking to that effect, David D. Anderson notes in his 1971 review of Twilight in Delhi:

That the novel was written in English was of significance in 1939, in those last days of the British Raj, as Ahmed Ali sought a publisher and a wider audience than the Muslim population of India could provide (81).

Ali himself lamented similarly about his novels, “If presented in Urdu, their [his characters] concerns would die down within a narrow belt rimmed by Northwest India” (xvi). However, others have argued that English offered Ali a way to avoid the reactionary violence of his fundamentalist Urdu-speaking critics, especially considering the public outcry against prior work like Angaaray and the PWM as a whole.

Within and beyond the novel, we encounter transitory subjectivities, author and character reflexively experiencing and redefining themselves within a marked discontinuity. Twilight, in this context, becomes a mode of knowledge, an in-between that resists description, a liminal (un)becoming that transgresses two imaginaries of seeming incompatibility, conjuring a discontinuum that is as generative as it is inertial. In the context of my work, twilight is a metaphor for language’s inherent in-betweenness and the centrality of miscommunication and cultural incompatibility in not only the mediation of existing subjectivities but also the creation of new ones. I locate my research within this linguistic twilight, investigating the transitory subjectivities that emerged and (d)evolved in response to English at the turn of Indian independence as well as the powers, specific sites—be it caste, class, or gender location—and motivations that informed this transfiguration. Twilight in Delhi is a powerful example of this transfiguration, of a markedly non-English family engaging, countering, and coming to terms with the subjective possibilities of a “modern” English imagination.