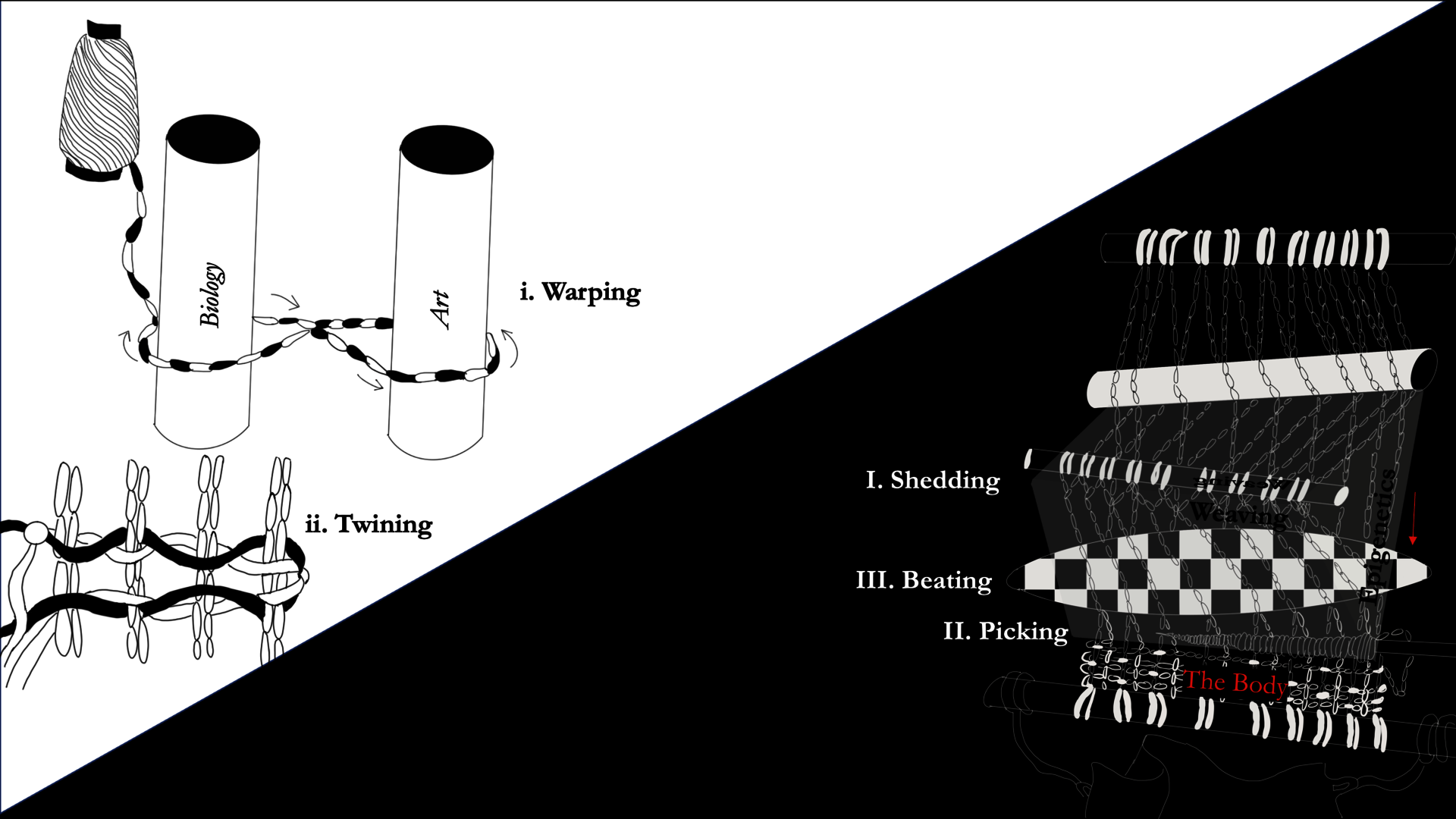

Shedding - Dividing warp threads into two groups.

Located high in the mountains of Central Mexico, tucked between the Sierra Madre Oriental and the Zacatecas, lies a sacred desert that bears the marks of the beginning of the world. The first women to trek the mountains of Wirikuta are goddess, Takutsi Nakawe, and her daughter, the corn maiden Niwetsika. Through a long and unfamiliar path, the mother and daughter lose sight of one another. Panicked to find Niwetsika, Takutsi gathers whatever she can to construct a loom. As the weaving extends and unravels to the floor, a channel of communication emerges from the land, revealing Takutsi the correct journey to Wirikuta. Soon after hearing of Takutsi’s journey, three curious and determined women decide they must see the mystical desert. Together, they lay the warp of the loom, pulling a series of lines that stand completely parallel to one another. Bringing the weft through a repetitive lull in and out, in and out, the goddesses weave until the same path reveals itself as it did to Takutsi. This is the first instance of weaving as told by current day Huichol Indians, and the birth of the first generation of Huichol people.

Two themes emerge from these initial observations of weaving traditions in Mexico from the Chiapas and Jalisco. First, materialization is seen as knowledge. The motions of organizing disjointed material provide information that cannot be seen, but shown, through geometric visions prompted by Peyote, or plant/animal allies collected on

pilgrimages. Second, knowledge is something that we inherit through physiological memory. Weaving is a ritual to summon the knowledge that remains beyond the reaches of one’s consciousness. Just as the weft transverses the warp over and under, a physical and mental migration through the borders of awareness is necessary to

obtain such information.

Western ideations of materialism do not predicate on what is inherited, but what is lacking. It produces to fill a void, rather than to reveal a path paved by sensation and intuition. Contrastingly, the epistemological significance of weaving is built on communication with ancestral ghosts. Where one does, but does not speak, the information threaded through the body.

Knowledge embedded into material is exactly how scientists in the 20 th century described deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA). In 1865, Gregor Mendel’s discovery of the infamous pea plant phenotypes suggested a vertical transmission of information in a controlled, non-randomized spread. Despite the world-shattering eureka, scientists remained perplexed. Collectively, they knew, there was a missing precursor to these phenotypic observations; a material capable of skipping across generations, carrying the necessary information required to communicate crucial information for embryological development.

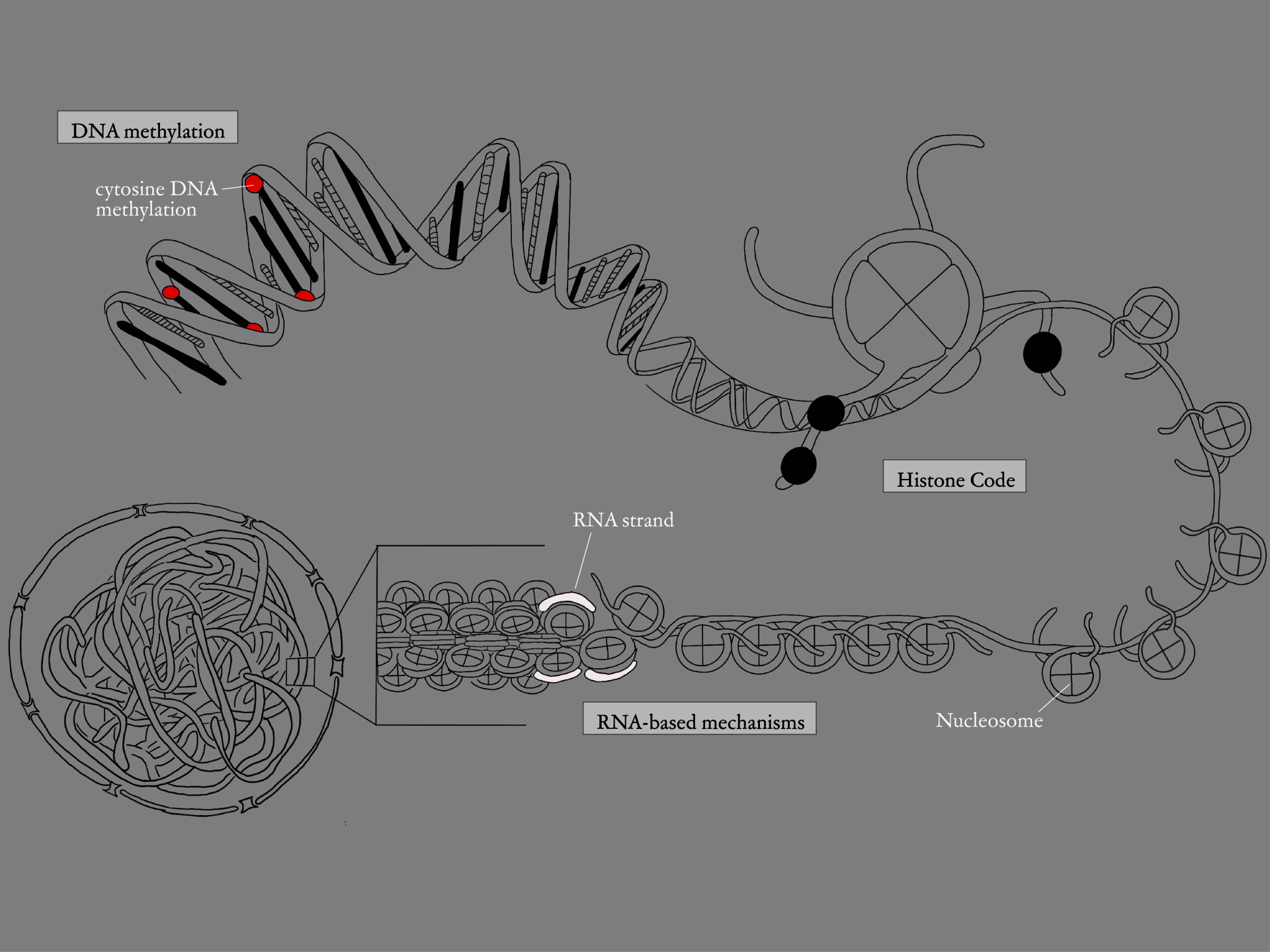

Naming the study of this material after the 17th century concept of epigenesis, Waddington was the first scientist to propose a language for epigenetic studies. The name, epigenetics, literally refers to above genetics (Greek prefix epi-, where the root translates to ‘upon’ or ‘over’). One modification is the muting response from methylation; where methyl groups attach to the DNA strand, blocking proteins from reading and transcribing instructions for further protein translation. This is just one example of an epigenetic modification. Epigenetics is more technically defined as phenotypic differences accounted for by change in gene expression, rather than alteration of the genome itself. Thus, chromatin modification and non-coding RNA (both physical changes to the structure and subsequent inaccessibility of the gene) are two additional illustrations of epigenetic modifications. Scientists commonly refer to the inheritance of this epigenetic pattern as genomic imprinting. For those not well-versed in scientific literature, it can be a difficult concept to grasp onto; since there are thousands of unknown biological phenomena that simultaneously promote and inhibit unseeable pathways, ultimately contributing to a much larger network of genetic expression.

Originally, my fascination with epigenetics spawned from my own individual research in a lab studying the homeostatic regulation of epidermal stem cells, and its reliance on nutritional balance in the insulin-IGF pathway. Countless studies have demonstrated that genes retain some type of memory of past experienced (lived or inherited); and that epigenetic regulators could be one physical materialization of these memories. This newfound conceptualization of trauma offers an object when we are lost for words. It gives meaning beyond the immediate or decipherable. But it is also sensitive to the environments designed, by and for, dominant forms of power.

I have spent half of this thesis discussing the material properties of epigenetics and weaving. They are objects that, like language-textiles, fray in multitudes. What makes the material properties of epigenetics and weaving so exceptional, is their ability to migrate across time and space. They represent objects that unify groups of people—migrating across borders of skin, consciousness, and time. Their connectivity is eerily akin to nationalist imaginary glue, but it differs in two ways. First, chosen groups containing fragments of this memory are decided through progeny, not sovereignty. Secondly, the materials themselves are inaugurated as a subject of inquiry. They do not subjugate the bodies they are originally possessed by but reflect a greater subjugation of bodies from the outside.