PROPELLERS: ALUMINUM & THE MYTH OF TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESS

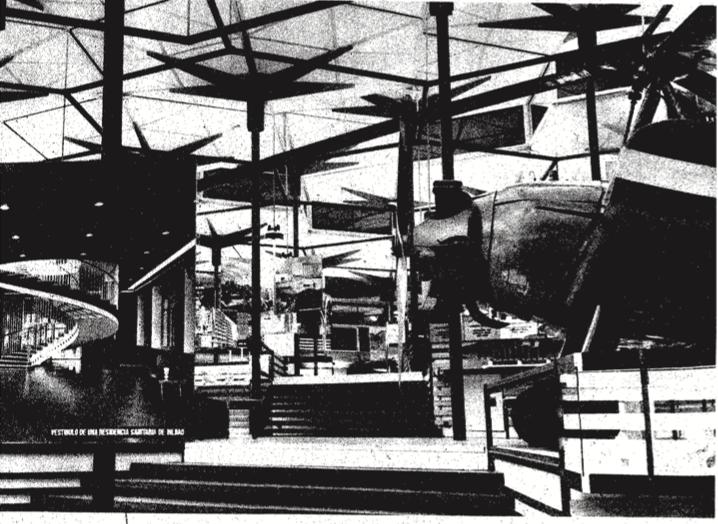

Propellers are the second key visual metaphor that reveal how Spanish aspirations for nuclear power were materialized in the Pavilion’s design. In broader terms, propellers in the 1950s have been associated with progress, movement, technology, and advancing civilization. Look at this photograph of the interior taken from the lowest part of the Pavilion showing the Autogiro invented by Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva. In front of the metallic six-fin capitals of the columns mimicking the propellers of aircrafts, the autogiro makes the space seem as the pavilion itself is taking off. This photograph, taken from below, creates a daunting vision of numerous propellers on a white sky.

Propellers symbolize military prowess in the Pavilion, which required the metaphor of an empty sky. Present both in the Pavilion and in the Tangier stamp, this empty sky was part of the colonial propaganda arguing that there is nothing in colonized Morocco and it needed the colonizers to make the most of the territory. In this article, I am focusing on very specific propellers that do not relate directly to the production of energy but were a necessary factor to it. I will discuss how propellers in military machines played a crucial role to form an alliance with the United States which would bring nuclear technology to Spain, and at the same time, would allow Spain to keep control of Western Sahara and its radioactive phosphates.

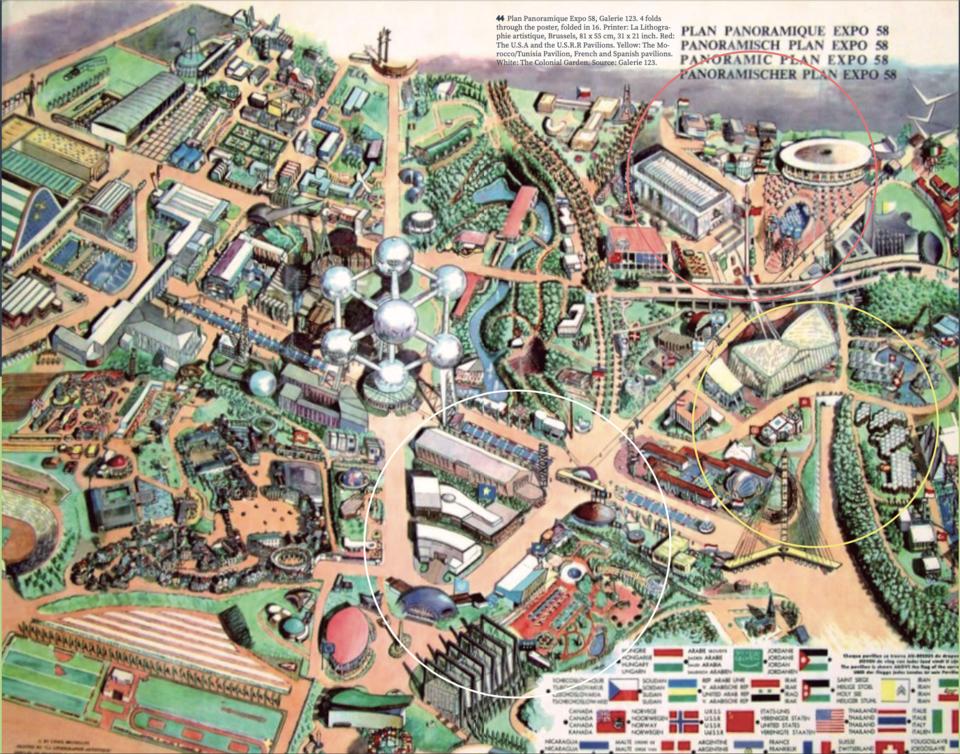

The Strait of Gibraltar was, together with Ifni, the main setting of Spain’s geopolitics during the 1958 World Fair. Since the late 1930s, and especially during the Cold War, these 7.7 nautical miles that separate Europe and Africa had become a geostrategic apex. In 1953, the agreement between General Franco and the United States President Dwight Eisenhower led to the installation of a US Naval Base in Rota, on the Spanish shore, with capability for nuclear submarines. In order to have a better understanding of this context of the Cold War it is important to look back at the distribution of the national pavilions in the Fair’s map, in which every design decision was strongly political. The Cold War superpowers—the USSR and the US were placed across each other (red circle in the map), as embodying physically the rivalry between both.

The architecture of the Spanish Pavilion, particularly the propellers, evokes aircraft with its materiality: aluminum. Despite the fact that the propeller-columns are built of steel for structural purposes, the facade, which is the key element that encircles and defines the quality of the space, is of aluminum construction. This light material, which in Spain had prior to the Fair only been used for aeronautics, was utilized for construction in the glassy enveloping of the Pavilion. This historic use of aluminum coincided with the pivotal moment of Spain displaying its technological and military power to the world against the backdrop of the Cold War, which leads me to believe that wrapping the Pavilion with aluminum was a deliberate political statement. Aluminum embodied the political message of a new nation that left fascism behind and ready to be part of international enterprises.

The material properties of aluminum go beyond its previously mentioned lightness. Aluminum is malleable, a metaphor of all the different shapes that a new nation can adopt, not anchored in the past formulation of Spain. Its high thermal conductivity, together with the glass facade that implied humidity in the interior, led to the design of a hexagonal heating network that hangs 80cm under the roof of the Pavilion. Considering such a technical effort to keep aluminum as the main construction material, we might ask ourselves why this was so essential in the design.

Probably the key characteristic of the pavilion favored by aluminum was transparency, which represented Spain as a reliable ally who needed the building to look like a glass cage with no secrets to hide. Contributing to the effort of the extensive glassy surfaces to blur the difference between interior and exterior, the aluminum profiles that framed the glass reflected light and helped diffuse the borders. Artificial lighting was also carefully studied to emphasize the transparent surfaces; in addition to the linear lights, focal points were hanging on each vitrine, and each of the vitrine frames incorporated miniature fluorescent Liliput tubes.

However, transparency was not only literal in the Pavilion, but also phenomenological. Architectural scholar Beatriz Colomina explains how in Mies and Der Rohe’s pavilion for the Barcelona World Fair in 1929: “nothing would be exhibited. The Pavilion itself will be the exhibit’’. In the Spanish Pavilion in Brussels, almost entirely empty, the different planes delimited by the columns create the illusion of various layers of transparency even when it is a diaphanous space with no borders. Corrales himself, in a lecture delivered in 2006, stated: “In that political era, doing this Pavilion was a miracle, it is hard to understand how it was possible. Of course, the original emptiness of the Pavilion was filled with machines by the Ambassador and the curators”. And he added: ‘‘It was necessary to keep the lightness and transparency of the space’’. According to Pendás,‘‘It was in the reception by the international media that the pavilion most clearly met the mark of the Franquista masquerade. The reviews contained only a faint shadow of Franquismo and assumed a country that was honest, as metaphorized by the structure’s lack of cladding”.

This demonstration of technological power presented Francoist Spain as a reliable ally to the US. In the night photographs of the interior of the building, the structure’s lack of cladding leaves visible the black propellers against the backdrop of the white sky to demonstrate technological power as a reliable partner to the US. Therefore, the moving Propellers against the static Palms became a symbol of Spanish colonial power in Morocco.The implications of these palms and propellers lasted decades after the Fair, as Spain only decolonized Western Sahara in 1975 after General Franco’s death. The image of a technological country able to extract resources prevailed and still today is a claim for sovereignty of Western Sahara against Morocco and the local Sahrawi people.