Jen Ansley

Folding (and Unfolding):

A Site-Responsive Strategy for Reusing Construction and Demolition Waste

Discarding—in its most reductive formulation— is a sorting operation that makes distinctions between materials (as well as objects, people, communities, and landscapes) based on perceived value. In her book Waste of the World, Nicky Gregson argues for a collection-curation strategy that revalues and re-signifies “waste” to make it available for repair and reuse. Gregson, however, points to limited space and infrastructural capacity as a potential barrier to the development of new material handling strategies.

My design responds with a modular building system that operates as an on-site waste collection-curation strategy while simultaneously illuminating the processes of construction, demolition, and redevelopment that have produced each site in its current condition. These processes are articulated through the fold as both a concept and formal design strategy that harnesses the waste on site and subsumes it into new forms.

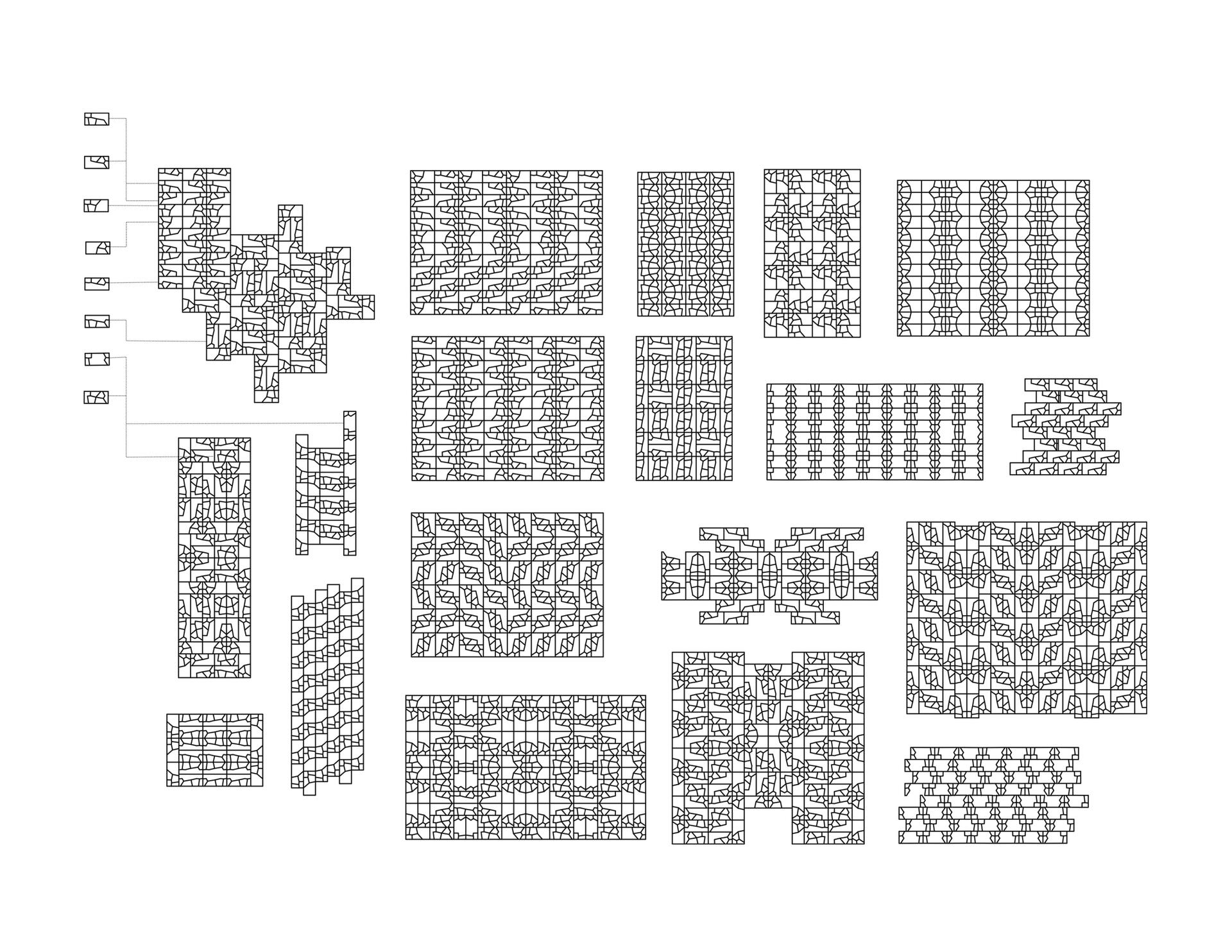

The fold appears in my thesis across scales, from the cellular composition of the clay body to the architectural form, and from the regional to the geologic flow of material, speaking to clay’s ability to reflect change over time. The network of brick walls that I’m proposing employ the logic and form of the fold, producing a system that is structural and yet modular, sticky, and pliant in its response to site, folding in the byproducts produced by urban economic transformation in the form of construction and demolition waste. This form was the the result of extensive prototyping that began with a series of conceptual drawings and clay models in fall 2023, where for me, the fold also helped to articulate sedimentation, force and flow, a mass and void as important material relationships.

Image

In the structure of my thesis, the clay brick itself unfolds and is reorganized into a modular wall/ path system at 2 major sites in Kingston, New York and the Lower East Side of Manhattan, responding to the material and ecological conditions on each site. As I move between sites, I simultaneously trace the historical flow of clay brick as a construction material that provided the foundation for extraction-based urban development in the Northeast and its transformation into waste, much of which now finds its way to vulnerable communities in the outer boroughs and upstate New York.

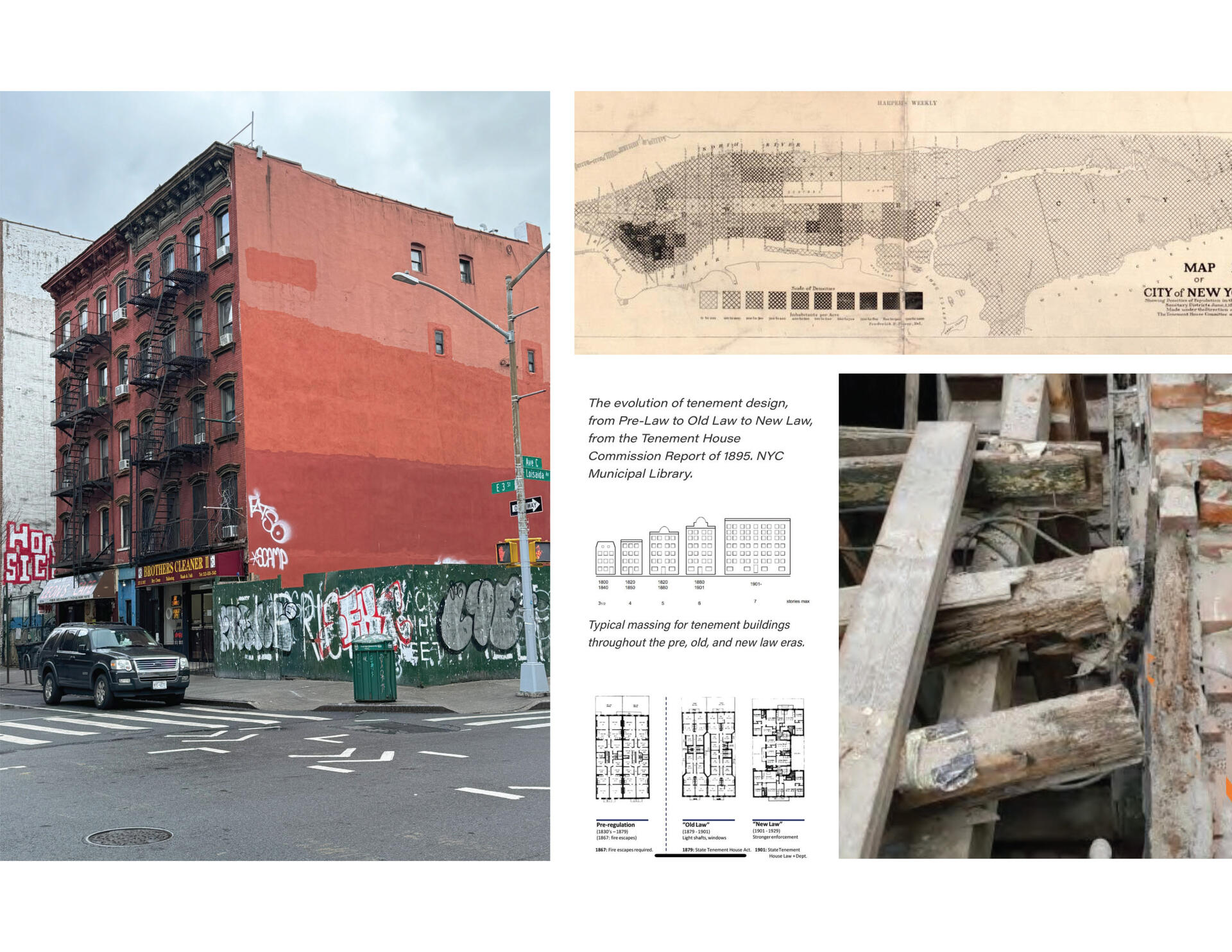

The material relationship between Kingston, New York and the Lower East Side begins in the 19th century when the Hudson River Valley was the largest producer of brick in the Northeast with over 135 brickyards operating along the river’s banks. Production was driven in large part by demand from New York City, where a rapidly densifying urban environment and a prohibition on wood-frame construction led to an expansion in brick construction, particularly in the form of tenements that housed primarily immigrant workers.

Image

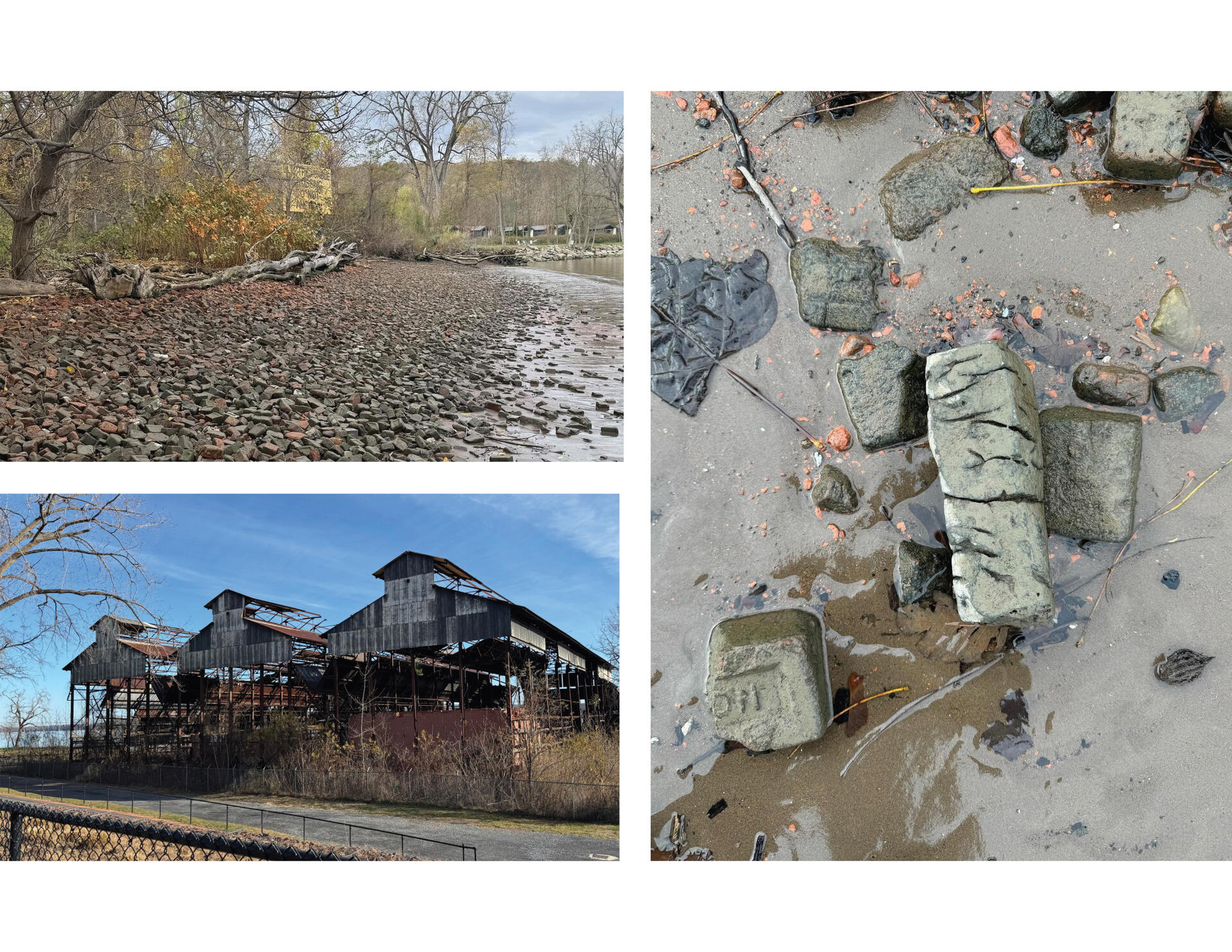

In Kingston, my wall incorporates rubble found on the beach adjacent to the former site of Hutton Bricks, which closed in 1980, after a hundred years in operation. Since 1980, the former brickyard has been transformed into a resort and event center built around its remains and a general aesthetic of decay that invokes nostalgia for a bygone industrial area. While the adjacent beach is accessible to the public, the brick on site makes the beach difficult to inhabit and its connection to the nearby Hudson Brickyard Trail is obscured by wire fencing and dense forest. An indirect pathway that crosses the lawn and cuts through the adjacent neighborhood provides the only connection. Meanwhile, vehicle access to the resort is restricted by a gated entrance, allowing pedestrian access only.

Image

The modular system I propose consists of 8 bricks that are in different proportions void and solid, and can be arranged to form a wall or path that subsumes construction and demolition waste into the structure in the wall while also allowing water to percolate through the system, acting as a form of stormwater infrastructure.

Image

Brick rubble is incorporated into the wall using the logic of dry-stacked stone construction. The pieces of the wall are mortared using natural cement, which is derived from a type of limestone known as clayey marl—first discovered in upstate New York in 1818. Unlike hydraulic lime, natural cement can better withstand wet, coastal environments like those found in the northeast, while requiring less processing and producing fewer carbon emissions than Portland cement.

Image

At Kingston, the system acts as part of a more comprehensive landscape strategy that is also designed to improve trail connectivity between the beach, resort, and Hudson Brickyard Trail; increase beach access while retaining the benefits of the novel ecology taking shape by clearing a portion, but not all of the brick waste; and provide a public seating area adjacent to the beach, all of which are currently lacking. And finally, the adjacent planting plan would work in concert with the brick rubble and my wall system to support stormwater filtration and phytoremediation on site with a particular focus on heavy metal accumulation.

Image

As we move to the Lower East Side, we encounter a different condition but one where this system becomes equally applicable. Fired brick—like that produced at Hutton Bricks—emerged as a mass-produced modular building component in the context of industrialization.

However, the design and construction of early tenements like this one at Avenue C & 3rd were guided more by norms and conventions than design standards and building codes. While minor improvements to the housing code where instituted in 1866 and 1879, they didn’t become standardized and regulated until the Tenement Housing Act of 1901. Many of these buildings are now at risk of structural deficiencies.

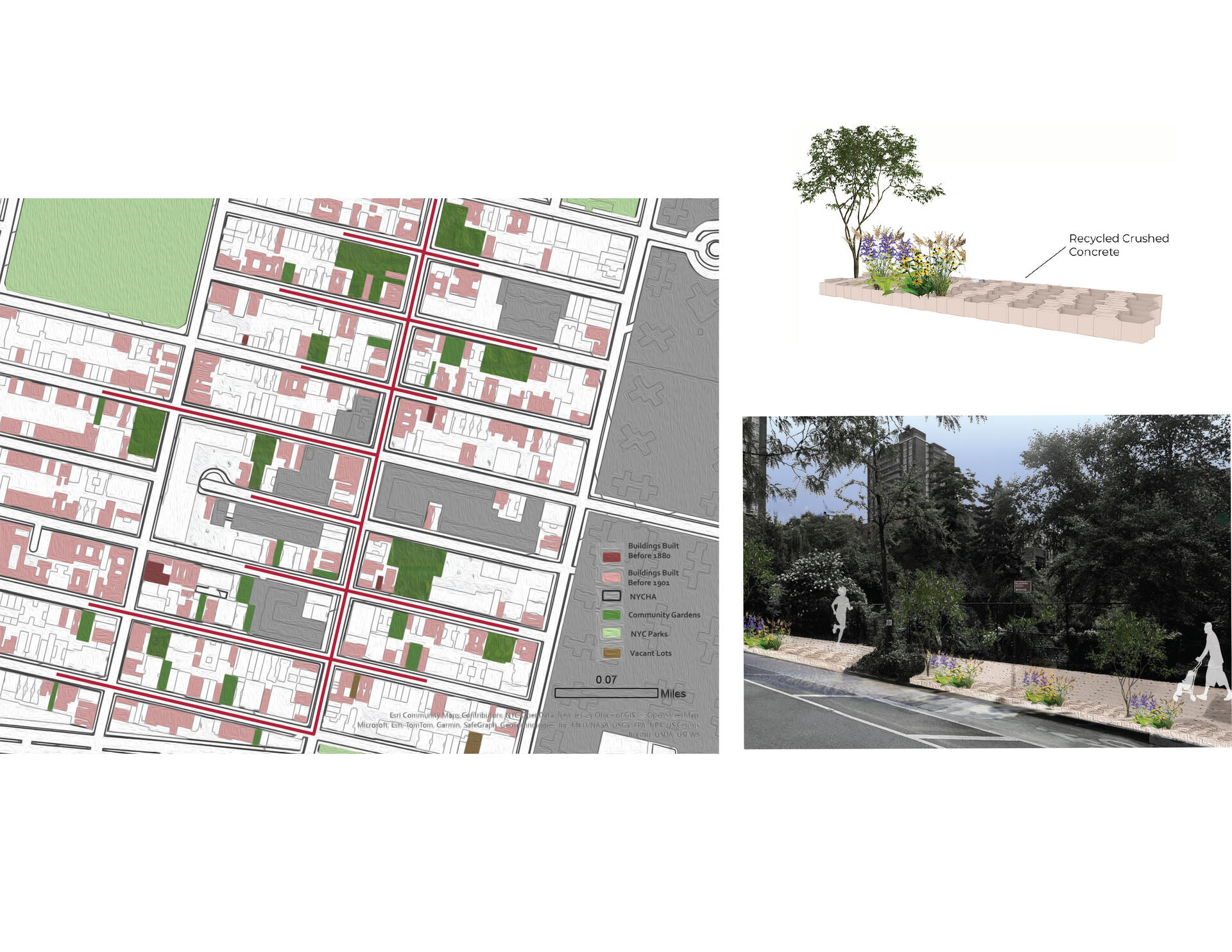

This map shows the number of buildings built before 1901 in the vicinity of Avenue C, where there is also a high concentration of community gardens, most of which were created on vacant lots in the context of a city-wide fiscal crises in the 1970s, during which property was left vacant, became vulnerable to arson, and was demolished.These gardens now act as significant stormwater infrastructure in the face of rising sea levels threatening to inundate the Lower East Side.

Image

My design proposes that concrete sidewalks along Ave C would be removed and processed into gravel that would fill the voids in these modules, instead of brick rubble. The modules would be oriented on the street edge to allow for the absorption and percolation of stormwater, while the remainder of the sidewalk would be replaced with whole reused bricks from tenements slated for demolition. In addition to reusing construction waste in a way that folds the history of the built environment into a plan that looks to the future, the path that I’m proposing would articulate the community gardens in the neighborhood as a network of spaces that provide green stormwater infrastructure and help to maintain local foodways.

Image

EXHIBITION IMAGES