PORTFOLIO

A Portfolio of Things That Go Together, Even If Not Obviously So

Conor Moynihan

For regular or occasional readers of Manual, one might recognize that the Portfolio feature includes a sequence of works from across all departments of the RISD Museum’s collection. These works all connect to the theme of the issue, but there is not a textual narrative that sutures them together. I depart from this format to include a short statement on why we should think about these particular objects as a group.

Variance ask us to consider how disability and illness are embodied and experienced, and how they have been represented by artists and deployed as visual tropes. When I first began to work on the exhibition component of this project, I was often confronted with a question that can be distilled down to this: Do we have enough work in the collection that could support a show on disability? After a preliminary search through the collection, the answer became a profound yes, with abundance. Relevant works could be found across time, media, and culture. Where, then, did this uncertainty of the presence of disability come from? I have some thoughts, which I shall sketch out here.

As Rosemarie Garland-Thomson so eloquently states in the first sentence of her introduction to this issue: “[D]isability is everywhere, once you know how to look for it.” Unlike questions about gender, race, and sexuality, which we are as curators increasingly accustomed to asking about our collections, the question of disability has remained a relatively unexamined one. Part of this issue, I suspect, is our framing of disability at the macro-sociocultural level. Often, in what disability-studies scholars name as the medical model of disability, human deviation from the so-called norm is treated as pathological and suspect. Human variation is viewed from a frame of desired normality, and advances in medicine and science promise to cure, correct, and resolve these differences. In so doing—and there is so much more that could be said on this—disability, illness, and human variation becomes hyper-individualized to this body-mind or that body-mind. We don’t understand these variations together under a shared sociocultural understanding of the normal and abnormal, but as two curiosities that are entirely divorced from one another.

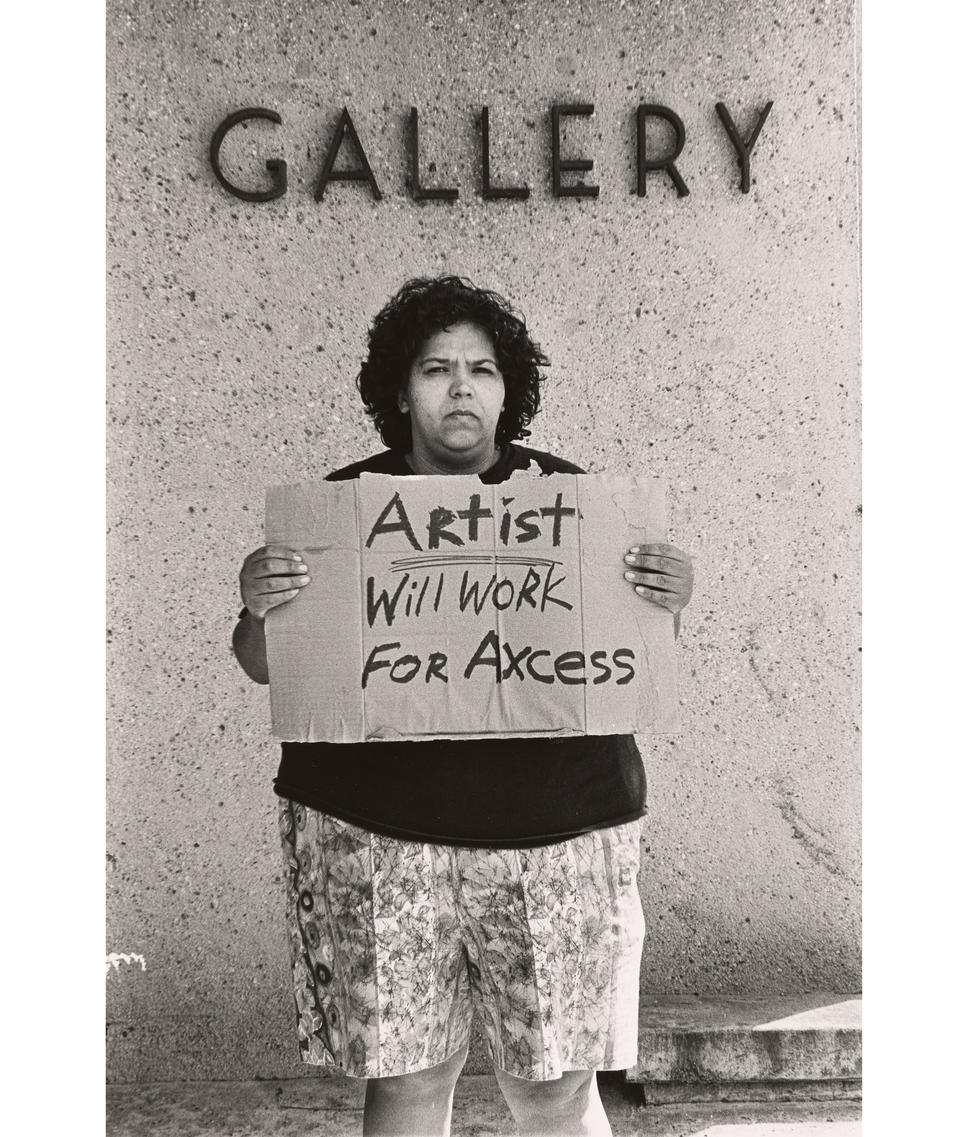

During the 1960s and 1970s, in contrast to what we would recognize as the medical model, disability activists—especially in the United Kingdom—began working towards what would eventually become known as the social model of disability. Under this understanding, disability is not reducible to forms of human variation alone, but intertwined with the structures of access that accommodate some forms of human variation as opposed to others. In other words, the experience of disability isn’t rooted exclusively in variation that needs to be moved toward normality, it is located in social, environmental, and architectural structures through which body-minds must navigate. The classic example of this would be a vertical building with many floors but only stairs and no elevators. In this building, disability is experienced by people who use wheelchairs and others who find the configuration of stairs inaccessible.

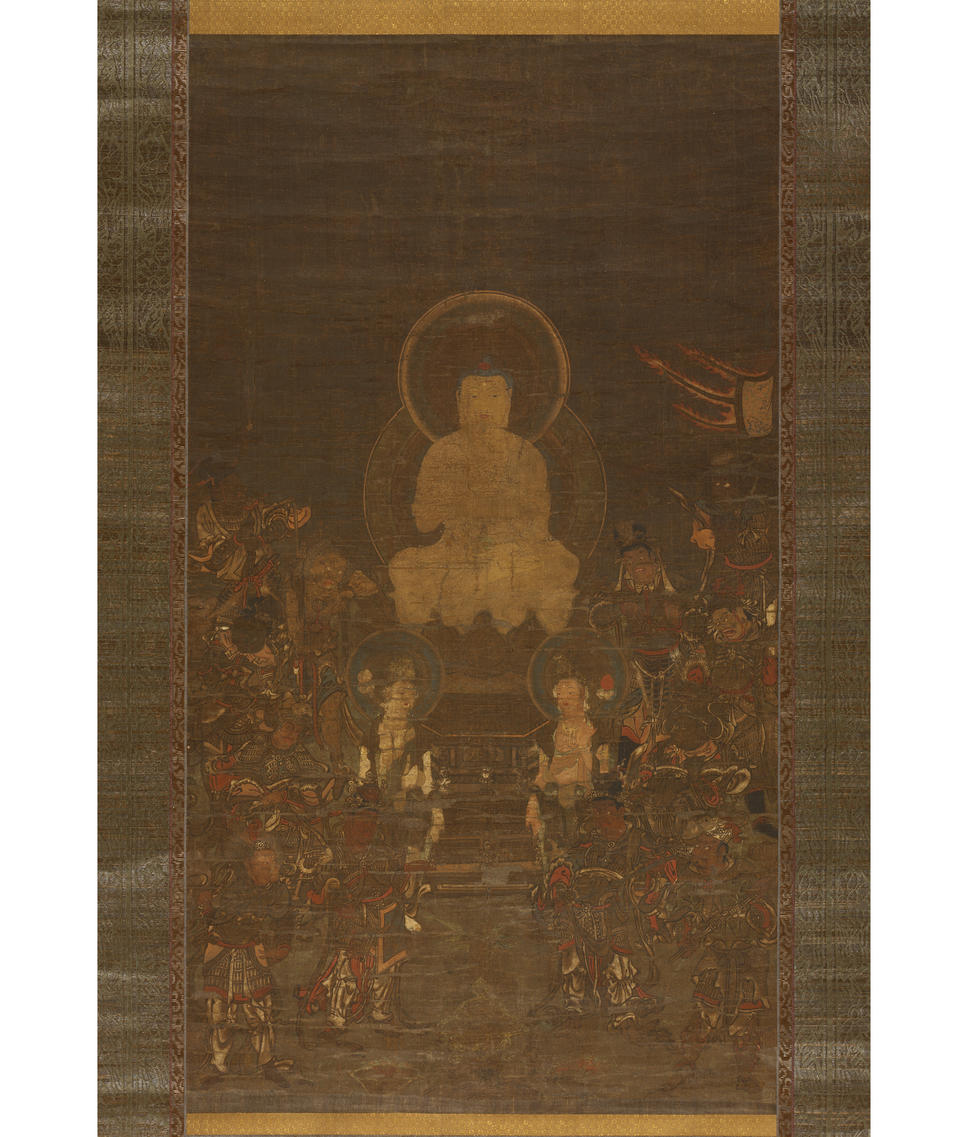

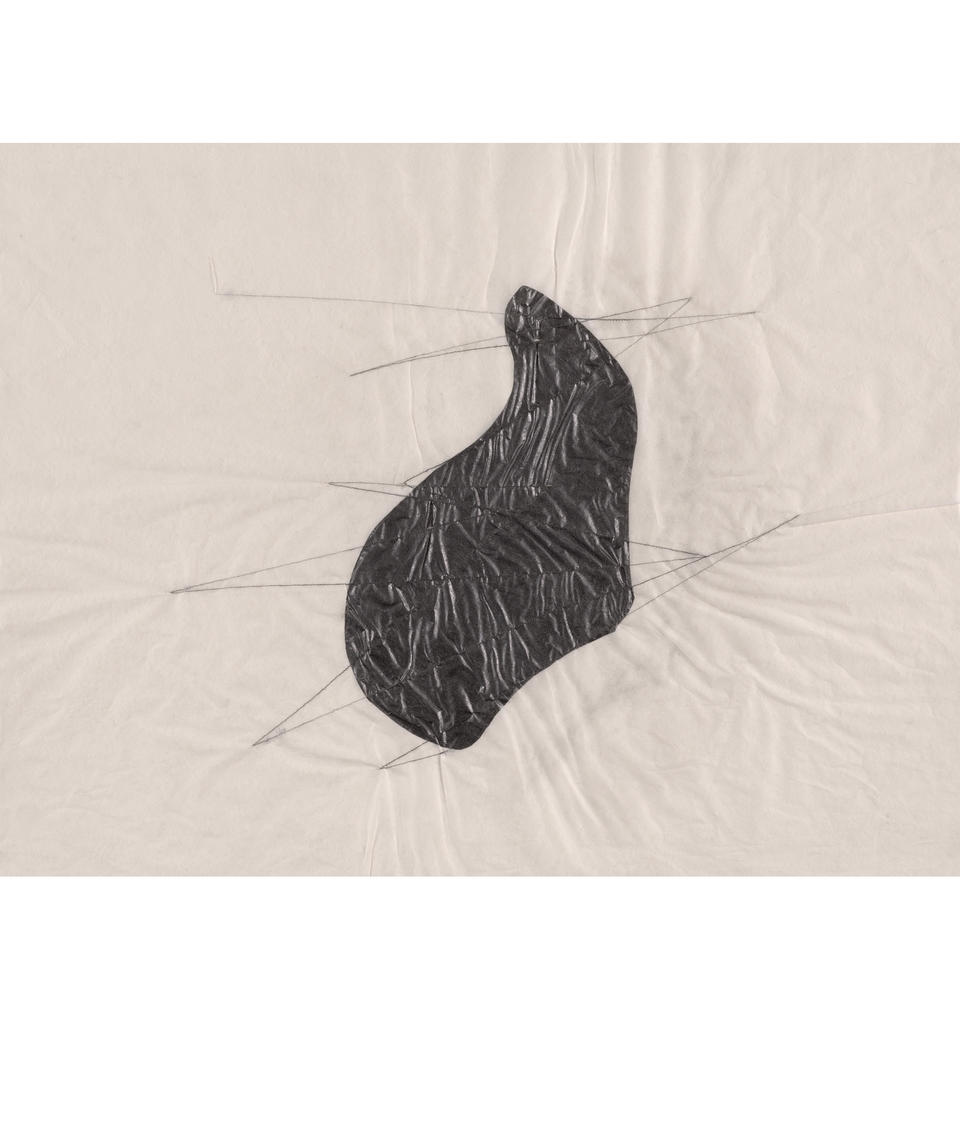

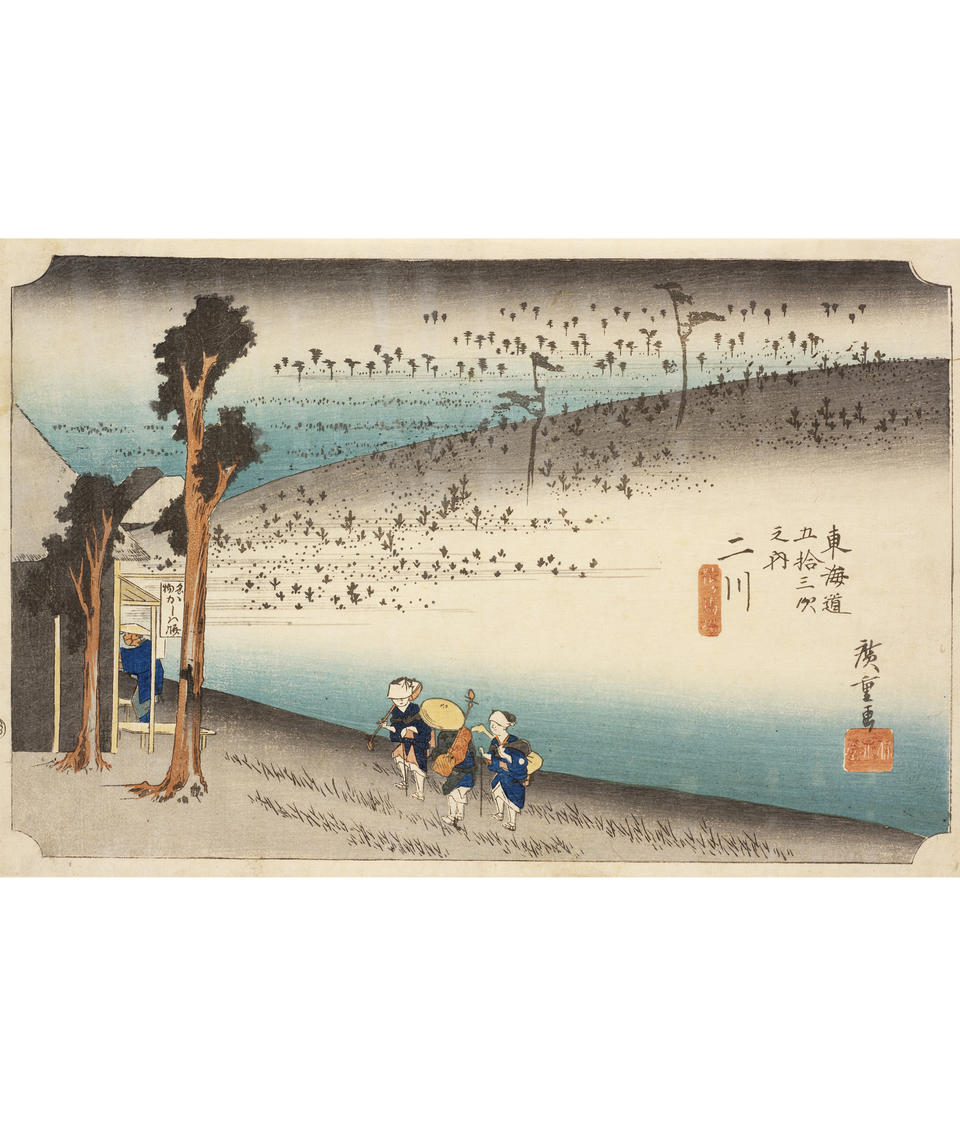

This illustrated essay takes to heart the social model of disability, which certainly has its limitations. But if we use it, we can consider how the works in this portfolio can be understood together. Human variation is not new—we have seen it throughout history. Likewise, craftspeople, artists, designers, and makers have inevitably responded to human variation. While disability is a modern concept, the following sequence of objects solicits you to think about the slippery and shifting perspectives of human variation, spanning millennia, from myriad representations locatable all across the globe.

Importantly, not all these works are made by artists who identify as having a disability or illness. Sometimes the disability or illness is visible within the work itself, and other times it was part of the making or the artist’s life narrative. Some works indicate the presence of illness or disease and signal a desire for cure. Variance invites you to consider what is gained, generated, or open to imagination by embracing disability as a critical framework through which to experience the world. We are, after all, incredibly varied in normative and sometimes extraordinary ways.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.

![In an etching on beige paper, a little person sits cross-legged among books, papers, and a pot of ink. He wears an 18th-century suit and wide-brimmed hat. Text at the bottom is in Spanish. Translated into English reads: “Taken and captured from the original painting of Diego Velazquez which represents the Dwarf of King Philip IV by Francisco Goya, [illegible] in the Royal Palace of Madrid, 1773.”](/sites/default/files/styles/half/public/2022-04/RISDM-48-418-150dpi.jpg?itok=xSXGui6b)