Jessina Lynn Leonard

First Sweet Truth

Image

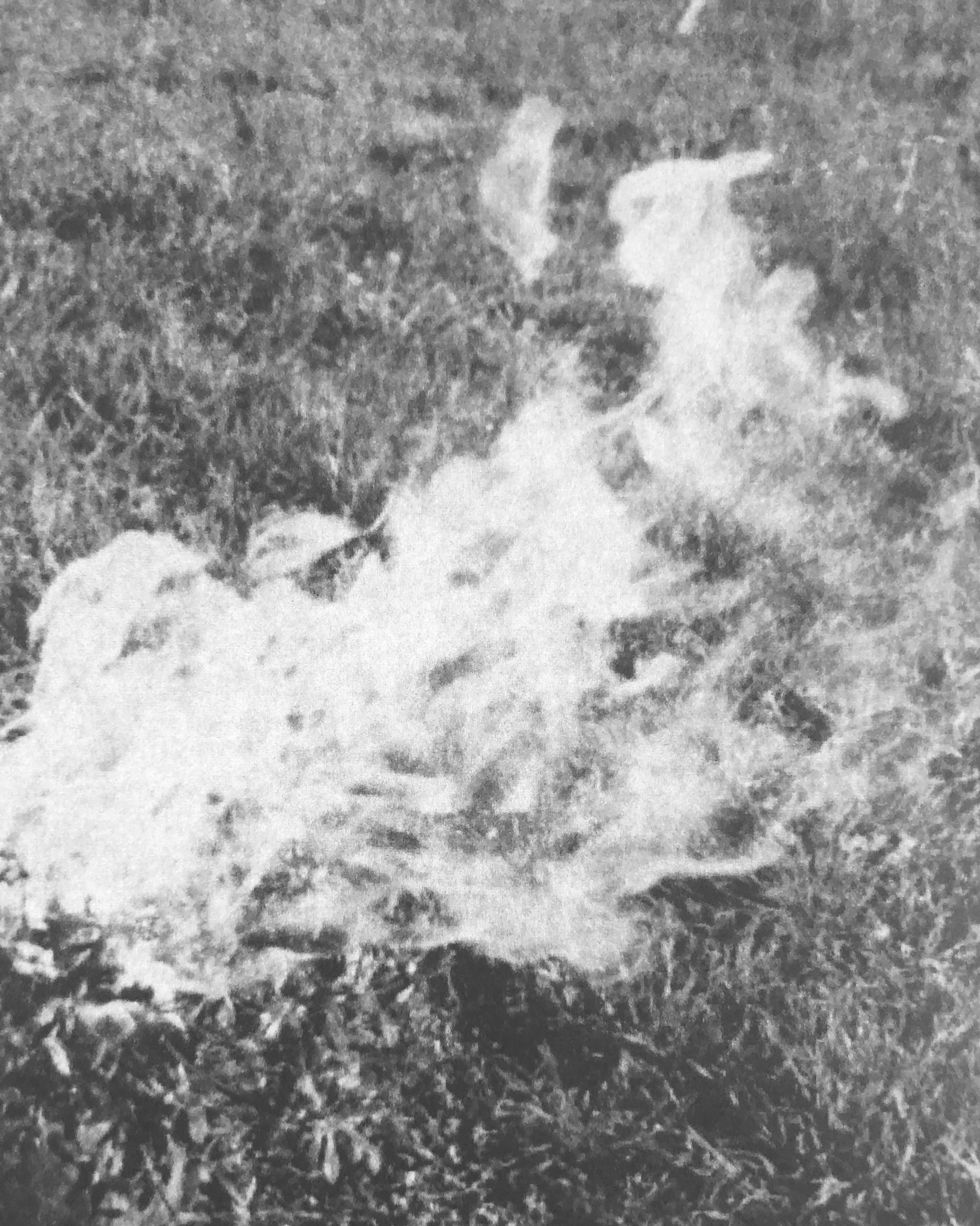

First Sweet Truth is a photographic dialogue with mystical texts written by Christian women in the late Middle Ages. These visionary accounts are not only significant historically—many of them are the first known texts to be written by women in the West—but, moreover, provide a foundation for non-anthropocentric knowledge. In our contemporary landscape informed by algorithms and data-driven forms of knowledge, mystical experience inherently defies the logic of our time. Today we largely assume seeing to be a disembodied act. In a constant flow of images, our eyes skim, understand, move on—what the philosopher Laura Marks calls seeing-as-mastering. In contrast, I examine what this lineage of female visionary experience reveals about other ways of seeing, a kind of seeing that gestures both towards the flowering of reality and the limits of representation.

My project is at once an historical inquiry, a personal pilgrimage, and an investigation into the continued relevance of these women’s writings. I turn to my camera as a tool of translation. How do you photograph the ineffable? For a medium that has an indexical relationship to reality, much has been written about photography’s ability to visualize the invisible, from Spiritualist photography to Kate Bouman’s recent photograph of a black hole. But rather than look to the camera as a tool for truth-as-evidence, I turn to it instead as a tool for truth-as-disclosure. What if the camera is the thing with which I keep saying God?

Image

Image

In my practice, the camera becomes the means by which I get close. Rather than attempting to create direct representations of these visions, I turn instead to fragmentation, emptiness, dissemblance, and the sensual, often using the symbols and metaphors these women reference in their own writings. In an effort to get even closer, my project has taken me to the very place some of these women lived in central Germany. Kloster Helfta is a still-active Cistercian convent where three of the most prolific Christian female mystics—Gertrude of Helfta, Mechthild of Magdeburg, and Mechthild of Hackeborn—all lived in the thirteenth century, and where many of the nuns today have even taken on their names. For them, it is still a place ripe with the presence of God.

Image

Image

Image

Image

When I first arrive at Kloster Helfta, the door is locked. With three cameras and a tripod strapped to my back and no cell phone service, I wait, cupping my hands above my eyes to look through the window, searching for some evidence of movement. With nothing else to do, I turn and face the pond across from the convent. A blue-gray heron walks along the water’s edge, one foot slowly placed in front of the other, before suddenly bending low and lifting his wings, flying over the convent, his feet dangling. They look like Christ’s feet in the crucifix at the church, feet that could equally be interpreted as dead or in a state of ascension.

After ten minutes, Sister Pauline shows up at the door and apologizes. “Have you seen the heron?” she asks. “I’ve been trying to take a picture of it for years, but it flies away as soon as you get close to it.” She pulls out her phone and shows me a few attempts, wings barely a distant blur in the horizon, cropped off by the edges of the frame. We talk briefly, our words hushed in the silence of the convent, and she shows me to my room.

Image

Image

Image

The next time I visit, Sister Christiane, the prioriess, comes to my room to show me the archive of Kloster Helfta. The sisters keep mentioning it, so I ask to see it. It turns out it is a small, cardboard box full of a hundred or so photographs in no apparent order, some of the reconstruction of the building and some from the personal family photographs of nuns who have since passed away. Before Sister Christiane shows them to me, she pulls out an envelope from deep within the pocket of her habit. “Perhaps this is silly, but I want to show you this picture.”

She slips out a silver gelatin print, its edges dimpled and curling. “I took this as a child and I am still so proud of it,” she says, and passes it to me. It’s a photograph of a horse—“what is that, fohlen?” she asks—asleep in a field, the child-sized shadow of Christiane evident in the bottom right corner and the horizon line askew in the distance. It is impossible to get close to a horse when it is sleeping, she explains, because it always wakes up. “I tried for years to get this photograph and I finally got close enough.” As she tells me this, I imagine her face looking the same some forty years ago when she first developed the print in her father’s darkroom. But, laughing and taking the print back into her hands, she says: “But when I see its left ear, I think it had heard me.”

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

One evening before dusk, I meet Sister Sandra outside of the church. What starts as a mixture of broken German and English quickly turns to wild gestures, laughter, and frustration. I have been told by the prioress that Sister Sandra, the resident amateur historian, has an idea of where the mystics of Helfta are buried. Of course, no one actually knows. Hundreds of years have passed and there are no records. Moreover, the land where Helfta is located is particularly swampy for the region, not an ideal place for burials. Sister Sandra tries to explain to me her elaborate theory for why she thinks the mystics might be buried directly in front of the church, something to do with the length of the nave (we walk, side-by-side, counting out forty-six meters together), and how the length of the church equals the combination of Jesus’ age when he died and the supposed age of the Virgin Mary when the angel Gabriel visits her (34 + 12 = 46). Sister Sandra explains that such an allegorical interpretation of the church’s architecture would be logical for the Middle Ages. I am fascinated, but still do not follow the link to the burial site, which she indicates is located just outside of the door to the church, practically beneath the western wall of the nave.

As we stand there together, looking down at the stone walkway, imagining the bones that may lie beneath, I look up at the exterior wall of the church. I point out a slight, curved indentation in the wall, which I have noticed each night as I walk back from vespers to my room. During the day, it is difficult to make out, but at night, a nearby lamp post casts a shadow on it, revealing a scar in the stone. “Was ist das?” I ask Sandra, and unsurprisingly, she has an answer.

“Gertrude’s first vision,” she says, before acting out the narrative that I am now familiar with, in which Gertrude has a vision of Jesus on the other side of long a hedge of thorns. She tries to get through it herself, before Jesus lifts and carries her over to the other side. The scar in the wall is actually an old doorframe, Sandra explains, now filled in with stones, but which used to connect the dormitory with the church. As soon as she tells me this, I know exactly what I am looking at, as I recall how Gertrude had her first vision in the passageway between the dormitory and the church. The next day when I walk to my room in the daylight, I pass a wall of windows at the convent and notice the fuchsia flowers of a Euphorbia Mili reaching towards the sun.

Image

Image

Image

When the sisters gather around me to say goodbye, Sister Pauline reaches over to me and whispers in my ear, “Did you photograph the heron?” Not yet, I respond. I’ve tried for two weeks and still have nothing—haven’t even gotten close to it. “Well,” she says, “photography takes a lot of patience.”