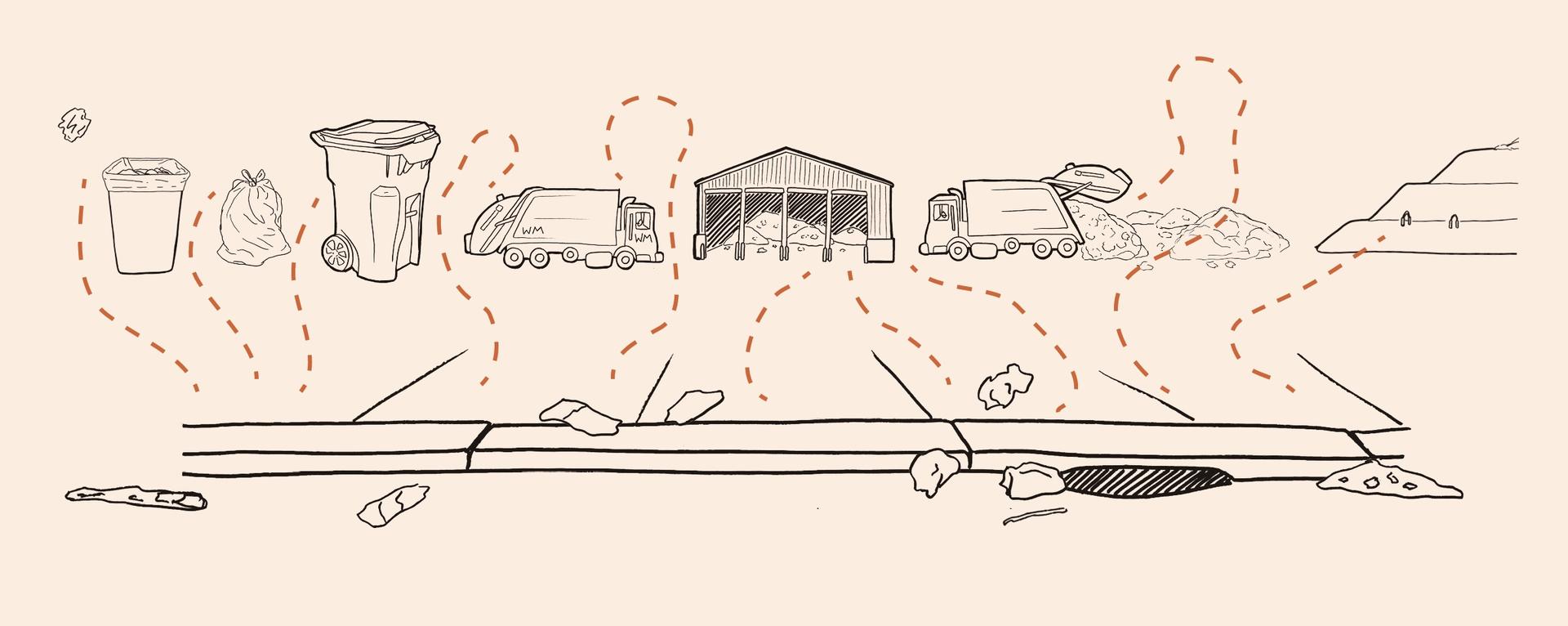

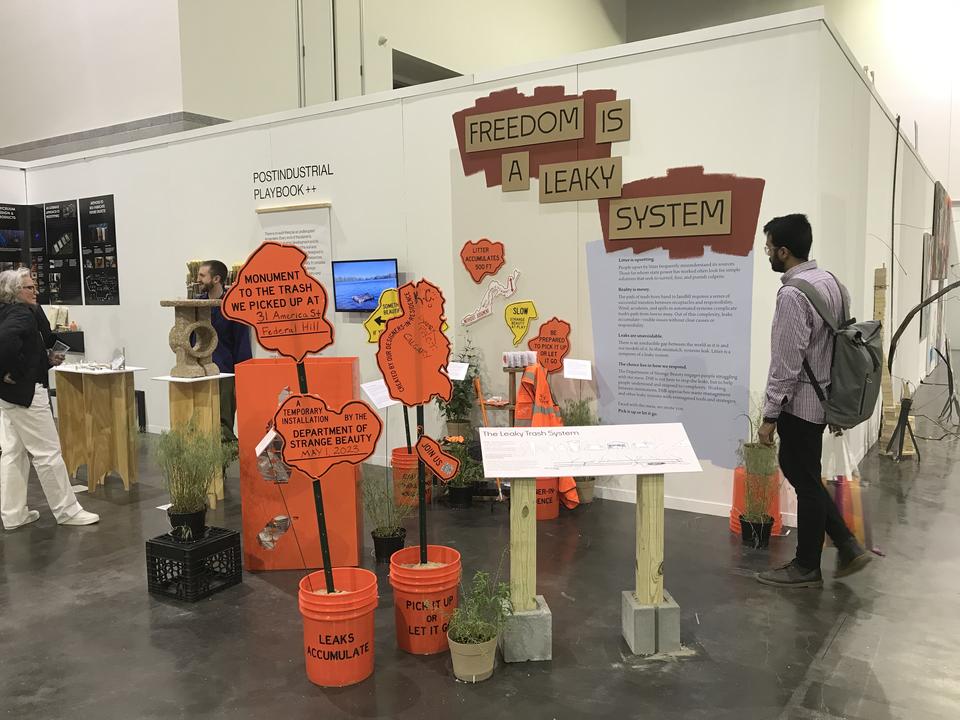

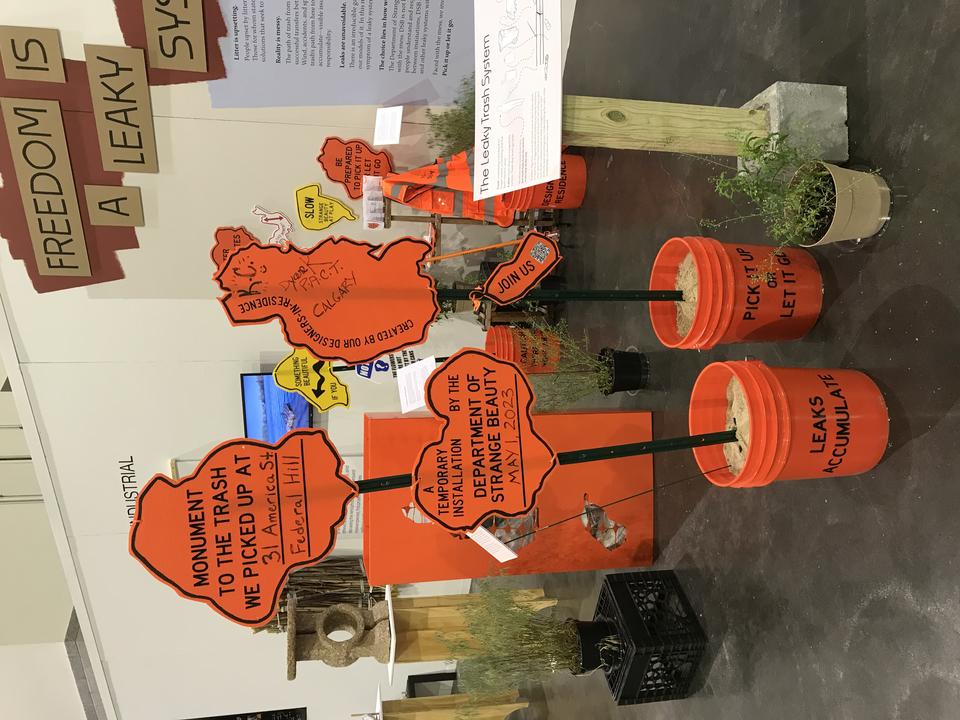

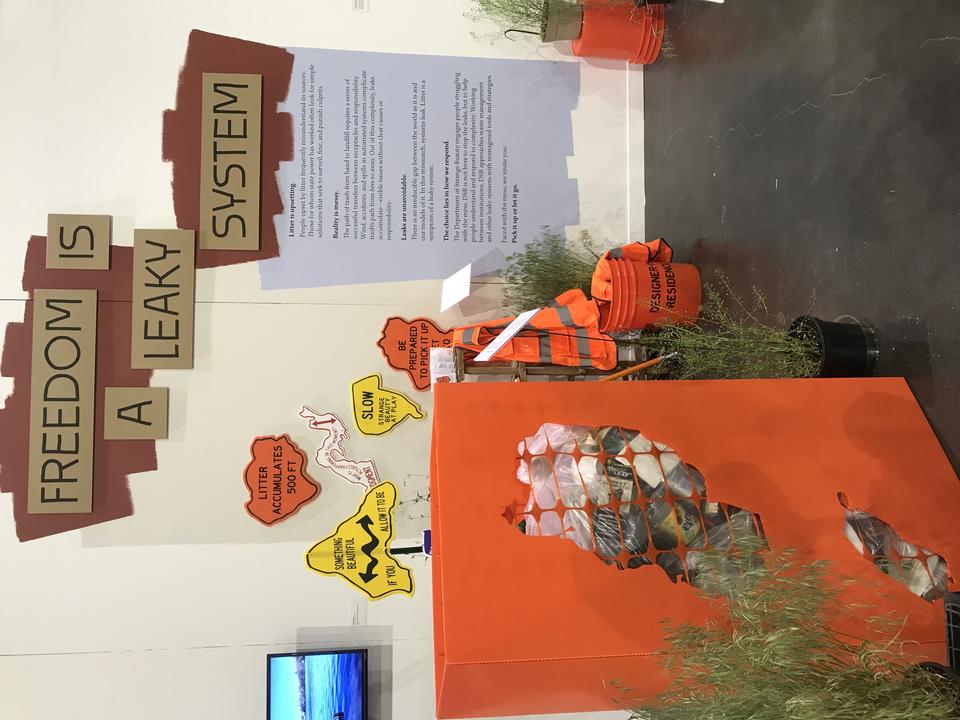

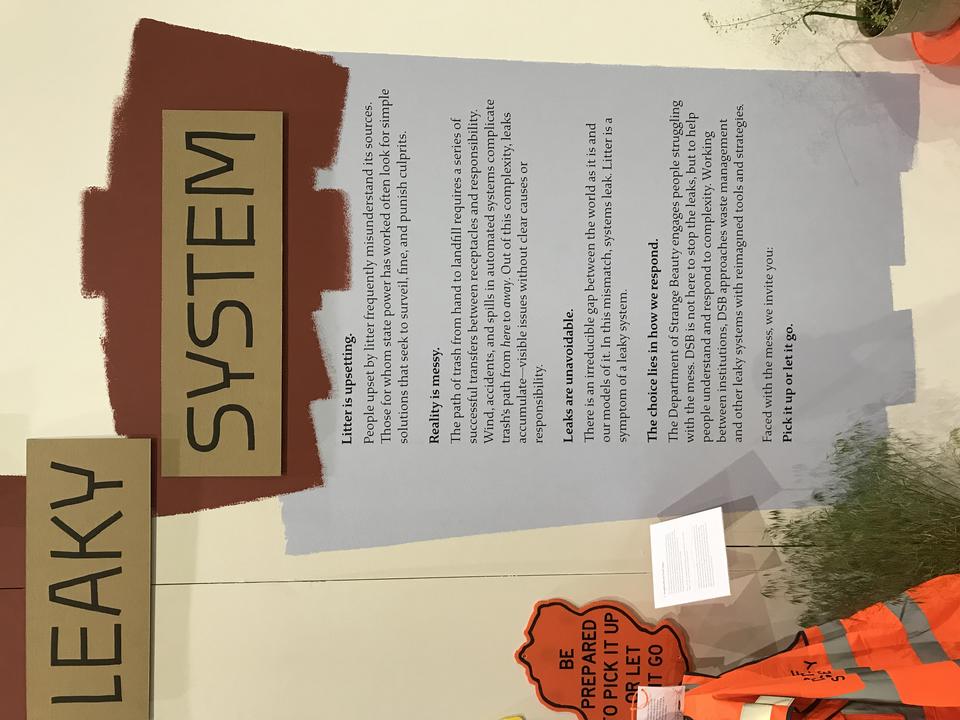

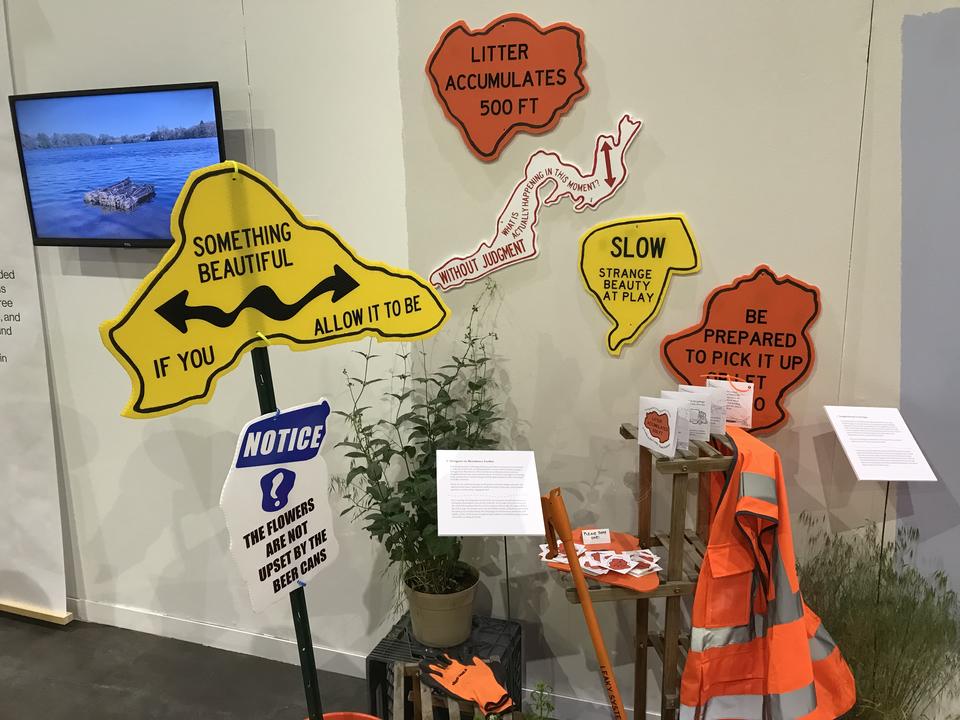

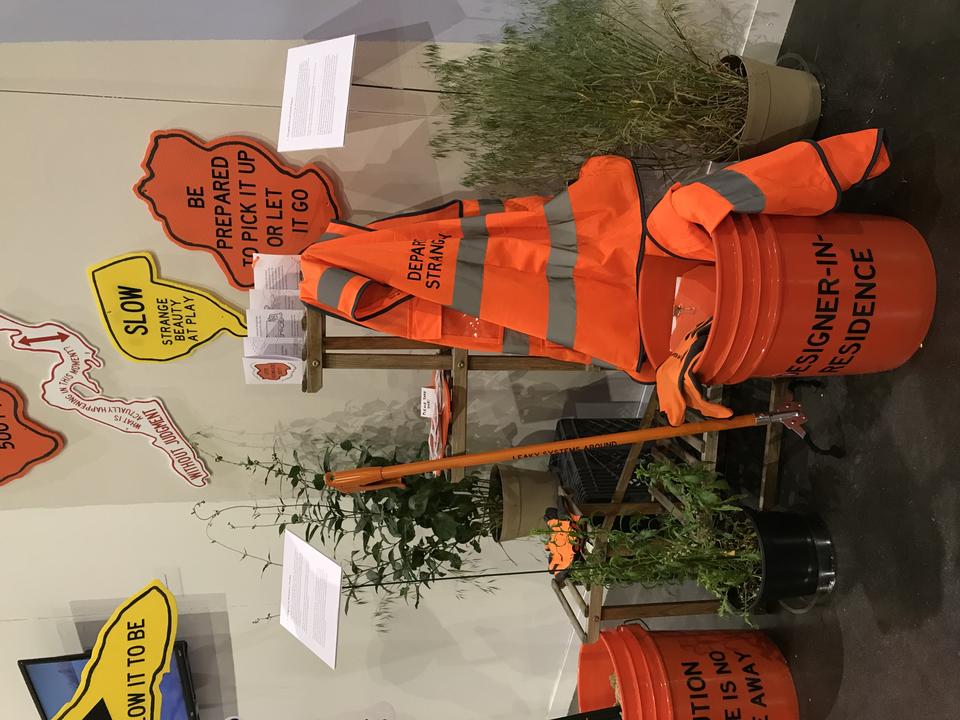

The Leaky Trash System

Trash: Something considered no longer useful; something that has been thrown “away.”

Litter: Trash that has escaped the system. Trash that won’t go away.

We think litter comes from a personal moral failing, but trash leaks from the system at every step of the way.

* * *

I visited the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Center for a Full Facility Tour in April. Trash was blowing around everywhere. Driving around the landfill, our tour guide Bill explained that they tried their best to curb the amount of trash blowing around, and to limit how far it could go. Still, trash blows out of tipping trucks, off of the landfill, and catches (mostly) on tall perimeter fences and a few moveable fences that are put around the active tipping area. “On a windy day like today, it’s awful,” Bill commented. (Most days are windy). Bill was frank: crews come to clean up around the property, but it is “almost an impossible task to be completely clean all the time.” Something always gets by the fences: “It’s a never-ending problem.”

At the Recycling Center, there is human intervention at every step of the sorting process, checking the work of the technology that does the bulk of the sorting. At the end of the recycling processing line, at the workstation of someone Bill said was the last person to touch the paper stream, the volume of erroneous sorted material was massive. The man worked so quickly, identifying wet-strength cardboard, plastic containers, and plastic bags by sight, pulling them from the rapidly-moving conveyor. He shoved the plastic bags into a large trash can beside him, and occasionally had to stop to stuff the plastic down into the bin to make more room. Everytime he did so, more pieces of plastic flew by, presumably to be baled up with the paper. The entire recycling facility was littered with material that had once been airborne, blown or tossed off of machinery and conveyor belts to the floor or onto ledges. The entire place was coated in a thick layer of furry, gray dust, an anonymous amalgamation of all of the plastic, paper, glass, and metals that moves through the warehouse each day.

The leaky system is on full display at RIRRC. I mean no shame in this. It is eye-opening to see how a facility completely dedicated to the management of waste, engineered to process it, is still a leaky system. These leaks are tolerated because of the costs of running the facility. A perfectly clean and accurate system would cost municipalities too much, make recycled materials so expensive as to make them unsaleable. We could have a more costly system, but we would have to be willing to care about trash that much more.

* * *

We can’t always know where a plastic bag blowing across the street comes from. In the complex mess of waste management, we can’t perfectly seal everything away. Plugging leaks and cleaning up requires investing more time and money into the system than we do now. Understanding the reality of the system helps us choose how to respond.