Floating Island

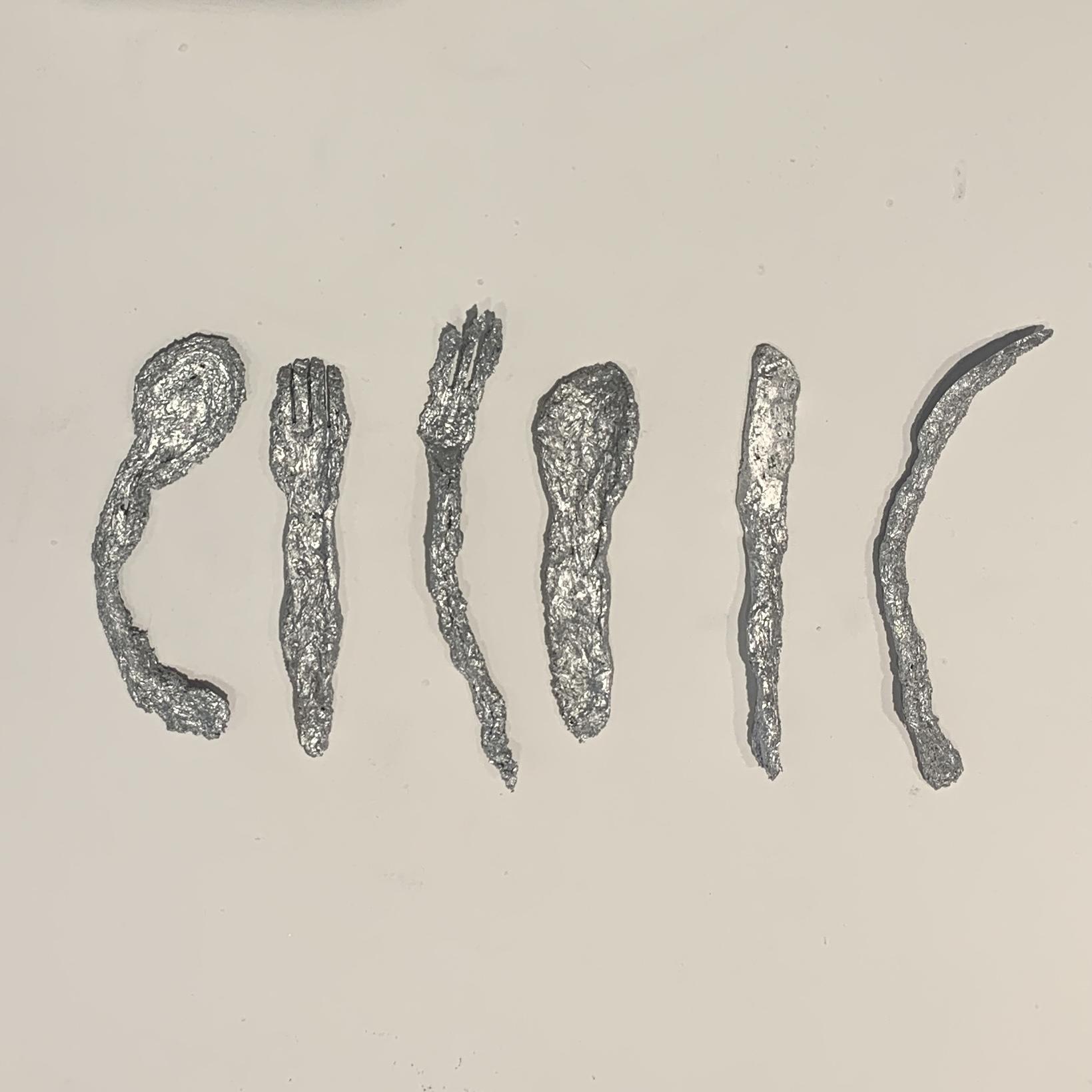

The first object, in collaboration with Augie Lehrecke (FD 14), Matt Muller (FD 14) Alexandra Ionescu (NCSS 21), Hope Leeson (Critic, NCSS), and Holly Ewald (UPP Arts) is a floating island made of knotweed bundles. Each bundle was harvested from either Mashapaug Pond, Morley Field in Pawtucket or East Side Train Tunnel Valley. At its roots, it is an Island made of invasive species in the middle of a polluted pond. Using the pollution of Gorham Silver on Mashapaug Pond as a case study, this raft will use their byproducts to instead regenerate the environment.

In essence, this product develops the bed for a floating wetland as a way of containing but also harnessing this abundant resource. It has a discursive function, referencing the introduction of invasive species and ornament, as well as bundles, subverting a symbol of fascism. It also has an ecological function of providing a bed for plants to grow and extract toxins that resulted from chemical waste. In this way, the goal is to craft a postindustrial cycle based on abundance rather than extraction.