Image

DOUBLE TAKE

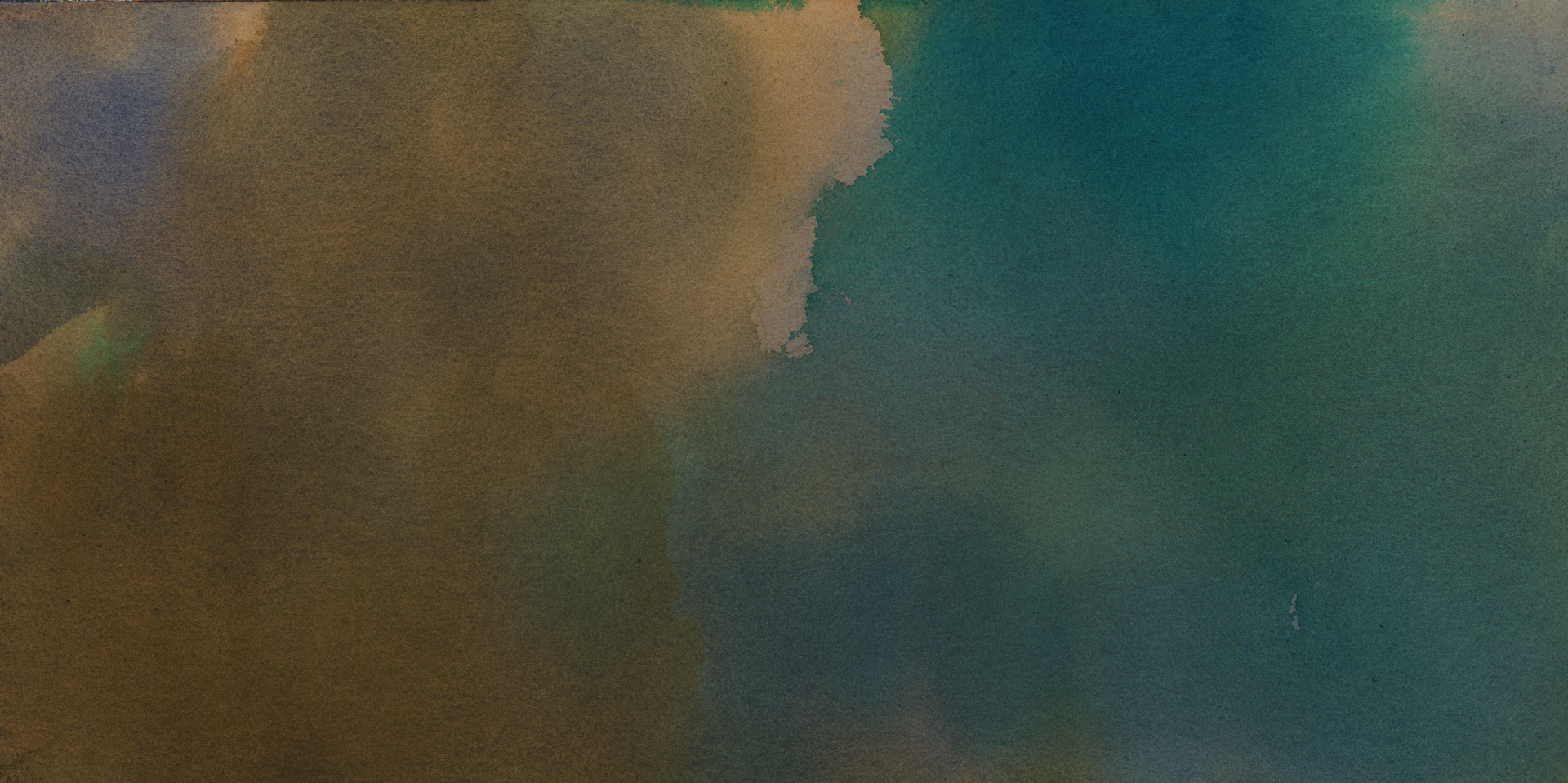

Remembered Landscape

Maureen C. O'Brien / Carmen Papalia

Thomas Sgouros (RISD BFA 1950, Illustration; RISD faculty 1962–2007)

American, 1927–2012

Remembered Landscape 14 • VIII • 96, August 14, 1996

Watercolor on paper

Sheet: 50.8 x 54.6 cm. (20 x 21 1/2 in.)

Museum purchase: Gift of the Artist’s Development Fund

of the Rhode Island Foundation 1998.83

Courtesy of the Estate of Thomas Sgouros

and Cade Tompkins Projects

Editorial Note: Thomas Sgouros discusses his practice and how his loss of sight shaped his work in this NetWorks Rhode Island video.

Image

Maureen C. O’Brien

—

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.”

— William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads, 1798

Thomas Sgouros’s remembered landscapes are anchored in visual experience, stripped of extraneous evidence, and reduced to essential motifs. He perfected this language of landscape painting as a mature artist, when diminished sight prevented him from recording specific views. The theft of tangible references was excruciating to a lifelong draftsman, but his mind’s eye held a trove of impressions informed by nature and by works of art. He channeled those recollections in a reinvented practice in which subject became sensation, and floods of color, like musical chords, replaced individual notes.

Tom was a master of line and illustration. His still-life paintings paid homage to Chardin’s homely vessels, illuminated from unseen windows. He carefully placed familiar objects in staged tableaux where they reflected glancing points of light. The result was a marriage of drawing and painting in which translucent interiors floated within firm contours. The exchange of those defined forms for fluid veils of color was an act of daring, which he performed like a trapeze artist releasing himself from the bar. The leap of faith required a revised methodology and the disciplined construction of a memorized palette. With this new kit of tools, he forged an expansive technique, opening windows to views of chromatic harmony.

A glimpse into Tom’s teaching practice at RISD hints at his reservoirs of optical information. When he brought students to the museum’s print room to examine British and American watercolors he internalized a wide range of techniques. In the turbulent washes of Turner and Sargent he discovered abstract fields of color and atmosphere. But he also studied Winslow Homer’s 1889 Hunting Dogs in a Boat, in which opaque pigments dapple the coats of attentive hounds and saturate a bank of autumn foliage. Another favorite was Thomas Eakins’s Baseball Players Practicing, depicting two members of the 1875 Philadelphia Athletics team in crisply detailed uniforms. Curious about Eakins’s process, he would follow the bands of sun-bleached grass, pursuing their watery flow beyond the edges of the window mat.

Tom was fascinated by the ever-changing effects of natural light and by the ways in which a simple mark could conjure the activities of daily life. He found both in the watercolors of George Chinnery, a British artist who spent much of his career in India and China and whose figures were conjured from animated curves. He later evoked Chinnery’s humid skies, faded yellow over the course of time. He was equally charmed by picturesque façades in Samuel Prout’s English towns, and by such humble observations as women carrying baskets on laundry day. In art and in life, he gravitated toward human interactions, and his remembered landscapes, while unpopulated, are an expression of that engagement. Forced to liberate narrative from his paintings, he replaced it with meditations on personal experience, re-envisioned in luminous horizons and in the lyric poetry of nature.

Image

Image

Carmen Papalia

—

When Sgouros was painting remembered landscapes I was committing landscapes to memory. A landscape from a photo that my mom took of me and my brother at Qualicum Beach on Vancouver Island. The clear sky made my eyes water, then burn. At the time I didn’t know that I would use that moment to explain how I saw.

I fill my pockets with skipping rocks. Large round stones grind beneath my feet as I step. The sound of marbles. I stand beside my brother, back facing the ocean, and squint. My mom’s silhouette in the sunlight. “Get closer, put your arm around him.” My eyes ache from the sun. White canvas. They water. I can hardly keep them open. They sting. I close them and try to locate her. Bright purple shapes. Blue. Shapes swirl across my visual field, flicker like a photo flash. My mom’s silhouette in the sunlight. Like Sgouros, I developed a system to help me document my visual memories. This was years after I stopped drawing, when my visual memories became vibrant and flat, like the characters I drew in animation school. My system came in the form of a manuscript called Pocket Vision, where I represented a different visual memory and mode of seeing in each page.

At one point I described my visual memories as something like a photograph, where the contrast and color saturation had been increased until the image had become abstract. Those photographs eventually became distant, as if they were stuck under layers of resin. They took on this quality as my access to the visual world became increasingly indirect.

Playing with glass marbles on a sunny day, for instance, became a contemplation on roundness. Perfectly round. A little bubble. The swirl of orange curls around the blue. A streamer. Floating, a bubble, stuck like a bug. Like glass, streams of colored plastic. The reflection of the sun shines right through it, catches the orange, blue on the cement, like a flashlight, like a magnifying glass. A spot of orange, light rolls, light across cement. A bouncing ball. A glass, through a glass.

Then I shifted value from the visual to the nonvisual, and they transformed once again. My visual references became animated in ways that transcended the moments they were placeholders for. Colors became ultra-vibrant. A luminous blue sky of the truest blue.

Image

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.