OBJECT LESSON

“Territories of the Self”

On Michael Mazur’s Images from a Locked Ward

Leon J. Hilton

Image

1

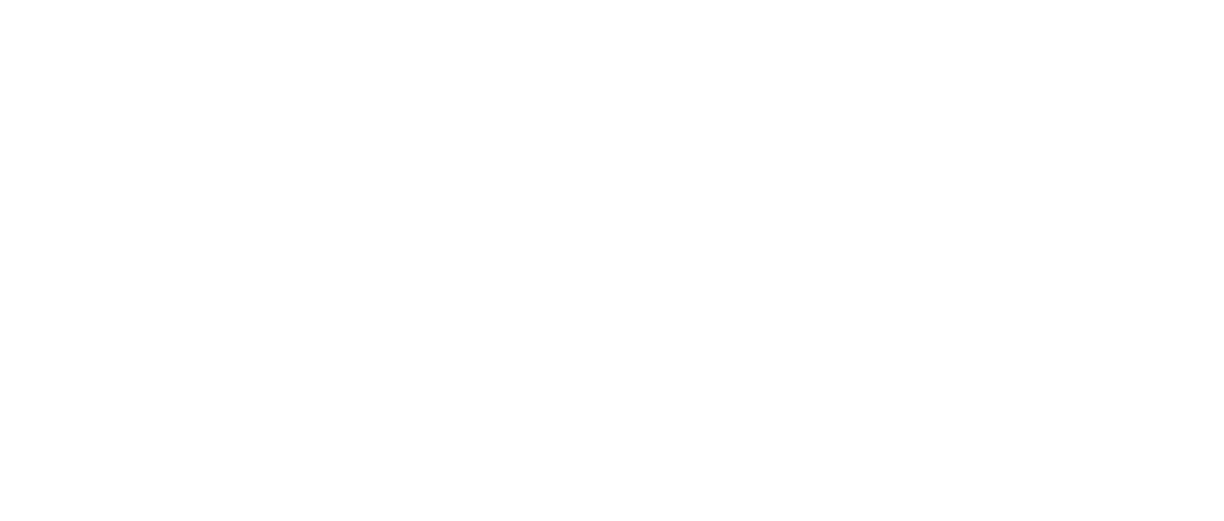

FIG. 1

Michael Mazur (RISD faculty, ca. 1961)

American, 1935–2009

Impressions Graphic Workshop, Inc., publisher

The Corridor, from the portfolio

Images From A Locked Ward, 1965

Lithograph on paper

Plate/sheet: 50.8 × 65.4 cm. (20 × 25 3/4 in.)

Gift of Jim Dine 80.266.2

© Michael Mazur; Courtesy of the estate of

the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

If we did not know from the title of the series that we are viewing images from a locked mental-hospital ward, The Corridor [Fig. 1] might suggest another setting, namely a perspectival view of a proscenium stage as seen by someone sitting in the audience of a theater. Proscenium wings are suggested by the curtain-like “legs” framing the stage, stretching back into the further distance. Abrasively sketched figures are perhaps walking, but more likely standing.

The Corridor is the second lithograph in Images from a Locked Ward, Michael Mazur’s series of fourteen lithographs printed in 1965 and published as a limited edition in collaboration with the eminent Boston lithographer George Lockwood. The lithographs are the culmination of a period of image-making shaped by Mazur’s firsthand observations of life in the psychiatric ward of the Howard State Institute of Mental Health in Cranston, Rhode Island, where starting in 1962 Mazur worked alongside his RISD students as a volunteer instructor in the art therapy program. The Corridor presents a view of asylum architecture’s orderly segmentation of space, designed to maximize the visibility of the human beings inhabiting it. The architectural elements function as instruments that are used therapeutically to manipulate the human beings. Yet the theatricality of the setting also enhances the sense of something chimerical, even ghostly, about the several seemingly human forms that flitter across the horizontal plane. Spectral and desubjectized, their faces are turned away from us or obscured by shadows.

Image

2

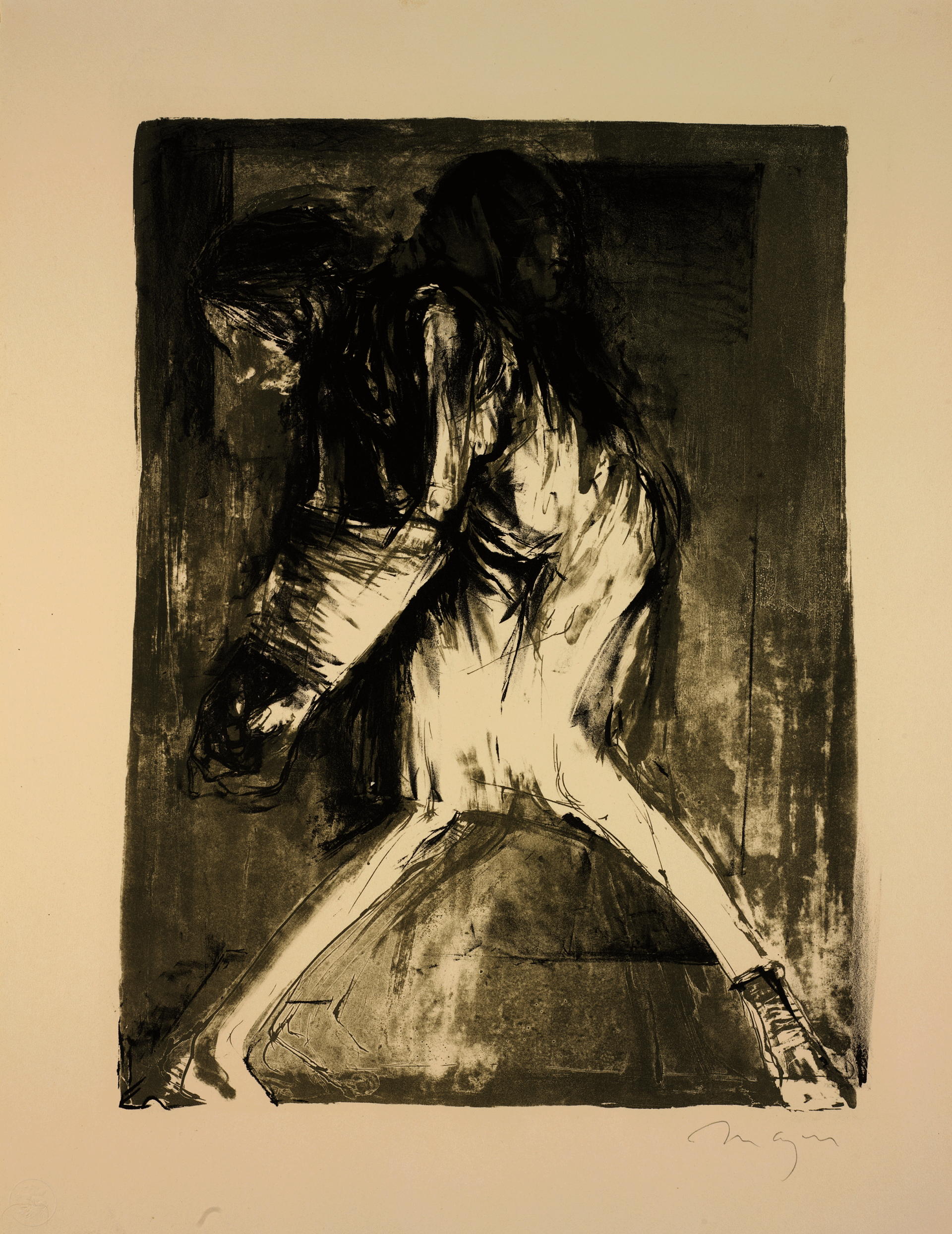

FIG. 2

Michael Mazur (RISD faculty, ca. 1961)

American, 1935–2009

Impressions Graphic Workshop, Inc., publisher

The Occupant, from the portfolio

Images From A Locked Ward, 1965

Lithograph on paper

Plate/sheet: 50.8 × 65.4 cm. (20 × 25 3/4 in.)

Gift of Jim Dine 80.266.3

© Michael Mazur; Courtesy of the estate of

the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

If The Corridor presents the asylum as a stage set, the image that follows in the Locked Ward series, The Occupant [Fig. 2], gives us a portrait of sorts: a medium-length shot that takes us closer to one of the figures. Here a figure sits slouched in wheelchair, body contorted at an uncomfortable angle as if to meet the gaze of the viewer head-on: the facial expression is intensely rendered but also difficult to interpret. It is a face that might be looking out at us with curiosity, smiling with a friendly greeting, or perhaps grimacing.

The Occupant reiterates in lithographic form a composition that Mazur first used in 1962 in an aquatint etching in his Closed Ward series. In it, finely cut swatches of shadowy ink made up of thin straight bands emanates diagonally from the back of the seated figure’s head to the upper right corner of the page. Contrasted with the rigid verticality of the lines used to designate the background walls and horizontal lines indicating the floor, this diagonal swoop suggests the movement of the patient’s head as he turns in his wheelchair in the direction of the viewer, in curiosity or surprise at the arrival of an unexpected visitor. In both the 1962 and 1965 iterations of The Occupant, the most predominant shape, and the source of the composition’s strangely radiant energy, is the wheelchair in which the subject is seated.

Image

Image

3

Image

4

FIG. 3

Michael Mazur (RISD faculty, ca. 1961)

American, 1935–2009

Closed Ward #9 (The Occupant), 1962

Zimmerli Art Museum

© Michael Mazur; Courtesy of the estate of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

FIG. 4

Michael Mazur, American, 1935–2009

Nightmare (II), 1987

Etching and aquatint with electric engraving tool

68 × 60.6 cm (26 3/4 × 23 7/8 in.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Gift of the artist in honor of Clifford S. Ackley 2005.864

© Michael Mazur; Courtesy of the estate of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Mazur would later note that these early etchings, based on scenes he’d witnessed at the Howard, were extensions of techniques he’d been developing in prints that evoked beds as tensile landscapes and the sleeping forms entangled in them. “The first Closed Ward print [Fig. 3] relates to prints like Nightmare [Fig. 4] and Sickbed, both in their expressive content and in their mark making,” Mazur observes. “They share use of a razor blade as a drawing tool and rely on the speed of the work.”1

Indeed, the visual tension sustained in these prints of unruly beds comes from the haptic mismatch between the soft pliancy of the objects depicted and the almost violent means and medium of their representation. In the etching of The Occupant, there is a similar attention to technique, making the image inseparable from the processes that subtended it.

Mazur’s works from this period are not exactly fixed, classified, and quantified through a generalization of the medico-psychiatric gaze. Nor do they easily fit into the documentary or journalistic impetus whose ethical force is animated by the desire to expose the deplorable conditions of mental institutions, and the brutality and neglect to which residents were abandoned. Instead, Mazur looks to a range of printmaking methods that date from the late eighteenth century. (According to the most widely accepted history of the medium’s development, lithography was discovered accidentally in the 1790s by a German playwright looking for an efficient way of making copies of scripts for his actors.) There is something out-of-time, or at least untimely, about Mazur’s use of these techniques in the second half of the twentieth century, well past the time photography overtook their original documentary, journalistic, and communicative purposes.

From the later 1800s onwards, aquatint etching and lithography become privileged artistic media for evoking the world of dreams, the unconscious, and the metaphysical. In The Occupant, Mazur nods directly to the pictorial inheritance of this tradition that is historically encoded into the medium itself. One precedent is Miserere [Fig. 5] by French artist Georges Rouault (1871–1958), exemplary in its use of the possibilities of lithography to render, through texture and tonality, something of the ineffable, spiritual force by which human suffering becomes the way for the body to transcend itself: a privileged route to seeking redemption from the earthly shackles of sin and imperfect flesh.2 In Miserere, human grief and physical suffering are suffused by the artist’s deeply Catholic sensibility, then arranged into a quasi-narrative series of mixed-media intaglios.

Image

5

FIG. 5

Georges Rouault

French, 1871–1958

En tant d’Ordres Divers, le Beau Métier d’Ensemencer une Terre Hostile (In So Many Different Ways, the Noble Vocation of Sowing in Hostile Land), from Miserere 1923, printed 1948

Aquatint, etching, drypoint, and photogravure

Collection of the McNay Art Museum,

Gift of Gilbert M. Denman Jr. in honor of the Right Reverend and Mrs. Everett H. Jones

© 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Rouault’s print series has tended to be viewed as an implicit critique of war and militarism, as well as an expression of hope for a world which such suffering would vanish. If the asylum becomes, in Mazur’s series, visible within a tradition that has the expressive possibilities of lithography as a medium to depict human suffering, it is doubtless significant to their abiding power that Mazur’s images were created during a period that was a genuine historical inflection-point in the viability of the institution that is being depicted. The several years when Mazur was teaching at the Howard Hospital’s psychiatric ward was a period in which the asylum would come to loom large in American cultural imagination. The asylum model, in these years, was increasingly giving way to continual pressure exerted by the never-resolved tensions between custodianship and cure. The Corridor, like The Occupant, makes visible what the historian of psychiatry Andrew Scull has called the asylum’s moral architecture, consisting of “buildings designed as therapeutic instruments.”3 The asylum’s physical presence, Scull further notes, was understood by its architects and proponents as operating upon the minds of its inmates in ways analogous to the role assumed by the invisible hand of the market in the regulation of civil society under industrial capitalism.

The history of the Rhode Island State Hospital itself offers a microcosm of larger transformations in psychiatry, medicine, and the politics of social welfare over nearly two centuries. The institution is located in Cranston, Rhode Island, on farmland purchased by the state in 1869 from the descendants of William A. Howard.4 Facing a crisis in the ability to manage both the increasing numbers of unhoused poor due to a mass influx of immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and elsewhere, the state government had found its extant early nineteenth-century asylums (including Dexter and Butler) inadequate. As Janet Golden and Eric C. Schneider note in their article on the history of the institution:

If frugality was to be the watchword of state policy, then the selection of a farm site proved to be ingenious. It allowed for the removal of the insane from the city, their isolation in more tranquil rural areas, and their occupation in simple manual labor, a combination that both state legislators and leading asylum superintendents found desirable. The asylum, which included the State Farm at Howard, was spread over 417.7 acres of land, and included pavilions for the insane, the state workhouse, a laundry, a chapel, and farm buildings.5

With the initial eighteen wood-frame buildings constructed in 1870, the Rhode Island State Hospital adopted the Cottage Plan building style. Understood by its inventors to be a progressive modernization of the earlier Kirkbride model of asylum planning, the Cottage Plan style reflected the precepts of asylum medicine, itself an outgrowth of the “moral treatment” model of care pioneered by English mental-health reformers such as the Quaker Samuel Tuke at the York Retreat starting in the 1830s.

Indeed, during this time, asylums emerged as architectural technologies to manage people and populations who are otherwise unmanageable, and who became visible to the emergent state apparatus as problems in need of management, control, and in many cases confinement. This approach applied not only people with mental deficiencies of various sorts that seemed to render them incapable of entering the labor force (and hence work) shy or delinquent. These categories justifying confinement in asylums also overlapped with the poor, the vagrant, the migrant, the drug addict or alcoholic, the “loose” woman, the “unsightly beggar.”6 From its inception, the state hospital and countless institutions like it practiced forms of care and custodianship that were designed to “instill the habits of order, regimentation and uniformity into increasingly stratified and heterogenous populations”—architectural and institutional efforts to regulate and rationalize the social chaos and anomie fueled by urban industrialization, poverty, and racial upheaval in the wake of the Civil War. What does it mean to consider the historicity of lithography, like that of the asylum, to be entangled with the maturation of modern state power and the material processes of technological consolidation through which the state came to realize new modes of power and authority?

Image

6

FIG. 6

Michael Mazur (RISD faculty, ca. 1961)

American, 1935–2009

Impressions Graphic Workshop, Inc., publisher

Bound Hands Swing, from the portfolio

Images From A Locked Ward, 1965

Lithograph on paper

Sheet: 50.8 × 65.4 cm. (20 × 25 3/4 in.)

Gift of Jim Dine 80.266.10

© Michael Mazur; Courtesy of the estate

of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Probably no other image in Mazur’s series hints at this historical tension more viscerally than the tenth print in this series of fourteen, which depicts an asylum patient whose forearms are bound together in a bandage-like cloth, suggesting that we are seeing a patient in the throes of a technique of hydrotherapy known as wet-packing. One way of understanding the scene is as a kind of degraded version of a therapeutic practice that was, by the time Mazur would have been present to witness it, used for purely custodial or even punitive means. In their account of the history of the Rhode Island state hospital, Golden and Schneider note that even though “the hospital claimed that hydrotherapy cured acutely ill patients, it is obvious that it was used most frequently as a form of restraint, a fact which the hospital tacitly admitted.”7

But if the image attests to the uncomfortable fact that such methods of bodily constriction persisted well beyond the time when they were understood to be therapeutically beneficial to the patients who were subjected to them, it’s also clear that Mazur’s etched lines and inky shadings do more than merely document this lamentable fact life on the ward. In Bound Hands Swing, the practice of wet packing is not simply documented as a damning sociological “fact” of reality—a practice that continued to take place out of public view, behind locked hospital doors, long after its medical or therapeutic benefits were debunked—as it might have been in a photograph.8 Instead, the scene is moodily evoked by the technique itself. The historical persistence of hydrotherapy as a form of control and restraint is viscerally suggested by the surface of the image: the still discernable traces of the liquidity of the ink hints at the wetness of the scene, drenching the image in an expressive drama that draws us in to look the body’s contorted terrain. The piercing and almost tactile quality of the image is a unique aspect of the mark-making afforded by the medium of lithography. Like the other prints in Mazur’s series, Bound Hands Swing seems to be reaching toward an additional, almost iconographic function, one that evokes a more generalizable experience of human unfreedom. It is an experience that is not just illustrated figuratively, but also evoked subjectively through Mazur’s deft handling of the particular kinds of shading, texture, and saturation that lithography enables.

Attending to the historicity of Mazur’s prints requires grappling with the continuities that link the time of the images’ making to the circumstances in which they are viewed today, as well as with the discontinuities that separate us from them. It is reasonable to ask whether the artistic visions and technical accomplishments that are so evident in these prints conflict with the historical conditions that defined the generalized landscape of suffering and dispossession, luring us into continuing ethical entanglements by virtue of the visual dramas of suffering and confinement they depict.

One way to consider how these images resonate in the present moment is to recognize that the same institution that provided the scene for Mazur’s prints continues to be a problematic and disavowed presence in the contemporary landscape, albeit under a different name. In the early 1960s, the Rhode Island General Hospital and Howard State Hospital for Mental Disease merged to become the Rhode Island Medical Center, and by 1970 vast numbers of long-term patients had been discharged for placement into “community-based care” settings, in line with the impetus of the nationwide movement to deinstitutionalize the large state-run asylums where mentally ill patients were being “warehoused.” In 1994 the institution became one part of the two-campus Eleanor Slater Hospital, named in honor of a state legislator who devoted much of her public service advocating for mental-health care.9 Under the auspices of a centralized state behavioral health agency, Slater continues to garner attention in local news for controversies stemming from years of mismanagement and chronic underfunding.

Any attempt to grapple with Mazur’s images must also query the moral status and ethical personhood afforded to the human figures they represent. What do these prints owe to the figures who appear in them, especially in light of the patient-led movements calling for the reform, deinstitutionalization, and eventually the abolishment of the asylum system that emerged in the decades after Mazur made them? After all, Mazur himself was not a patient in the hospital he was using as the basis for his artworks but merely a visitor, free to return home—or anywhere else he wished—once his art therapy sessions concluded. Moreover, while the Locked Ward series is legitimated by Mazur’s formal training (after studying art at Amherst and completing a printmaking apprenticeship in Italy, he earned an MFA with a focus in printmaking from Yale in 1961), artworks created by patients in psychiatric institutions often fail to be recognized, apart from the modernist fixations of art brut and “outsider art,” categorizations that have become inseparable from the fetishization of the “primitive,” the child-like, and other modes of antirationalism in the art market’s furious quest for authentic expression.10

Mazur’s status as a privileged outsider granted rare access to the closed spaces of the mental institution, allowing his series to attain a kind of testimonial function that stands outside the typical positions of patient, medical authority, or warden. Many of these images seem imbued with something like the cosmic, tragic vision of madness in the premodern world, which came to be eclipsed as “madness was appropriated by reason” through the emerging modern science of psychiatry, as described by Michel Foucault in The History of Madness—a text that was first published in French and translated into English during the years that Mazur’s lithographs were made. Yet even as modern psychiatry succeeded in inscribing madness into a medical discourse of mental illness—and as institutions were designed and rebuilt to keep pace with each new and seemingly more enlightened advancement in asylum medicine—Foucault maintains that “behind the critical consciousness of madness in all its philosophical, scientific, moral and medicinal guises lurks a second, tragic consciousness of madness, which has never really gone away.” This view sees madness as imbued with a “prophetic force, revealing that the dream-like is real and that a thin surface of illusion opens onto bottomless depths.”11

It can’t really be denied that Mazur’s prints leave behind the overdetermined and admittedly retrograde habit of aesthetically staging scenes of madness and confinement as elementally tragic tableaus of suffering. But they aren’t just providing a novel variation on a familiar tragic theme, either. In Asylums, his 1961 study of the mental hospital as a “total institution,” sociologist Erving Goffman describes the mechanisms by which psychiatric wards enact forms of mortification on the patient’s sense of self. Drawing from fieldwork conducted at St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital in Washington, DC, Goffman suggests that a defining feature of the total institution is the way that it violates the “territories of the self” and “objects of self-feeling—such as his body, his immediate actions, his thoughts, and some of his possessions.” In total institutions, Goffman observed, “the boundary that the individual places between his being and the environment is invaded and the embodiments of self profaned.”12 Perhaps in the turning our gaze from the stage-set-like scene of The Corridor, we can glimpse something akin to what Goffman observed about the constant, low-grade forms of refusal and resistance that were an ever-present, indeed necessary, corollary of the asylum system’s attempt to institutionalize total control—the fact that it is always and inevitably doomed to fail. As Goffman contended, “We always find the individual employing methods to keep some distance, some elbow room, between himself and that with which others assume he should be identified.” In this small distance, however miniscule, Goffman saw a tiny, glimmering and perpetually imminent of possibility of defiance, of holding on to the “embodiments of self” that the institution is designed to violate.13

Mazur’s lithographs now look back at us too, compelling us to ask about the ways in which looking at them renders palpable our own complicity in systems that constrain the freedom and autonomy of others. Writer Trudy V. Hansen describes the Locked Ward and Closed Ward prints as “dense and tortured,” suggesting that they “present haunting images of humans existing outside the civilized world, individuals who have lost their humanity and are left with only loneliness and desperation.” In the 1950s and early 1960s, Goffman perceived that “the practice of reserving something of oneself from the clutch of an institution is very visible in mental hospitals and prisons but can be found in more benign and less totalistic institutions too.” Goffman went on to insist that “this recalcitrance is not an incidental mechanism of defense but rather an essential constituent of the self.” If Mazur’s Locked Ward prints remain imbued with a certain tragic theatricality that may make viewers queasy, they also doubtless contain the traces of this sort of everyday low-grade recalcitrance, suggesting if we look long enough, we will find something about the persistence of the desire for individuality even in conditions that make it all but impossible to sustain.

In October 2020, while looking for information about a relative who had been institutionalized at the Howard Hospital in the 1930s, Cranston resident Maria da Graca discovered that in 1975, a state highway had been constructed over the area where thousands of patients in the Howard facility were buried.14 While state officials have now begrudgingly acknowledged this decades-old decision to secretly pave over the hospital’s mass internment site as a “mistake,” they have thus far failed to offer a solution that would adequately redress the long history of denying the personhood of institutionalized patients that this forgotten and paved over mass burial site so exemplifies. Instead, how might we look again at Mazur’s prints, seeing in their strange and unsettling hapticality—the switch point where sight meets touch, hand becomes eye—the grounds for another mode of witnessing, reflection, and, perhaps, repair?

- Quoted in Barry Walker, “Making Marks: The Edition Prints,” in The Prints of Michael Mazur with a Catalogue Raisonné 1956–1999 (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2000), 45.

- Rouault’s series of lithographs, made in the 1920s, recollect scenes of destruction and suffering wrought by World War I. These works are named explicitly as a precedent for Mazur’s mental hospital ward series by Lloyd Schwartz “Michael Mazur: The Poetry of Illustration,” in The Prints of Michael Mazur, 110.

- Andrew Scull, Psychiatry and Its Discontents (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019), 43.

- That parcel’s first European settler was William Arnold; prior to that, it was part of the homelands of the Narragansett Tribe. See https://www.warwickhistory.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=articl….

- Janet Golden and Eric C. Schneider, “Custody and Control: The Rhode Island State Hospital for Mental Diseases, 1870–1970,” Rhode Island History 41, no. 4 (November 1982): 114.

- See Sue Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: New York University Press, 2010).

- Golden and Schneider, “Custody and Control,” 122.

- Of course, numerous photographic and cinematic documentary projects have been crucial to the history of asylums and mental health institutions, often mobilized as evidence in support of efforts to reform or close them.

- See https://bhddh.ri.gov/about-us/our-history.

- See Hal Foster, “Blinded Insights: On the Modernist Reception of the Art of the Mentally Ill,” October 97 (Summer 2001): 3–30.

- Michel Foucault, History of Madness, ed. Jean Khalfa, trans. Jonathan Murphy and Jean Khalfa (London: Routledge, 2006), 26 and 28.

- Erving Goffman, Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates (New York: Anchor Books, 1961), 23.

- Goffman, Asylums, 319.

- See Tolly Taylor, “Hundreds of Bodies Discovered under RI Highway in Search for Gravesite,” WPRI website, https://www.wpri.com/target-12/hundreds-of-bodies-discovered-under-ri-h….

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.